Abstract

Parental discriminatory experiences can have significant implications for adolescent adjustment. This study examined family processes linking parental perceived discrimination to adolescent depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors by using the family stress model and incorporating family systems theory. Participants were 444 Chinese American adolescents (Mage.wave1 = 13.03) and their parents residing in Northern California. Testing of actor–partner interdependent models showed a significant indirect effect from earlier paternal (but not maternal) perceived discrimination to later adolescent adjustment through paternal depressive symptoms and maternal hostility toward adolescents. The results highlight the importance of including both parents and examining actor and partner effects to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how maternal and paternal perceived discrimination differentially and indirectly relate to adolescent adjustment.

Discriminatory experiences are prevalent in the lives of ethnic minorities (Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999) and can have a significant impact on ethnic minority adolescents’ adjustment (Garcia Coll et al., 1996). Adolescents are part of an interdependent family system (Cox & Paley, 2003) in which parents’ discriminatory experiences may influence children’s adjustment indirectly through family processes (Anderson et al., 2014; Ford, Hurd, Jagers, & Sellers, 2013; Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004; McNeil, Harris-McKoy, Brantley, Fincham, & Beach, 2014). Understanding the implications of parental experiences of discriminatory treatment is crucial to the study of child development in ethnic minority families (Garcia Coll et al., 1996). Although numerous studies have demonstrated associations between adolescents’ own experiences of discrimination and various negative developmental outcomes, including socioemotional and behavioral adjustment problems (Benner & Kim, 2009a; Grossman & Liang, 2008; Hou, Kim, Wang, Shen, & Orozco-Lapray, 2015), only a handful of studies have examined whether and how parental discriminatory experiences relate to adolescent adjustment.

This study investigates the family process pathways by which parental discrimination links to adolescent well-being, addressing several limitations of prior work. First, prior studies have usually included only the primary caregiver (Anderson et al., 2014; Ford et al., 2013; Gibbons et al., 2004; McNeil et al., 2014), thus failing to (a) separate paternal and maternal perceived discrimination experiences, which may exert differential effects on child outcomes given the distinct roles fathers and mothers play in families (Chuang & Tamis-LeMonda, 2009; Palkovitz, Trask, & Adamsons, 2014), and (b) take into account the interdependence between mothers and fathers (Cox & Paley, 2003). Second, although emerging studies have demonstrated the mediating role of parent–child relationships in linking parental perceived discrimination and child outcomes (e.g., Anderson et al., 2014), few, if any, studies have simultaneously examined other potential mediating family processes, such as the marital relationship (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). Third, prior studies in this area have mainly focused on African American families. Few, if any, studies have examined the association between parental discrimination and child outcomes among Asian Americans, a rapidly growing ethnic minority group (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). Findings from African American samples may not necessarily generalize to Asian Americans because Asian Americans are distinct from African Americans in many ways, including culture, immigration history, and family interactions (Julian, McKenry, & McKelvey, 1994; Xia, Do, & Xie, 2013).

To address these issues, the current study examined whether and how maternal and paternal discrimination experiences that were assessed when adolescents were in middle school would indirectly relate to adolescents’ socioemotional (depressive symptoms) and behavioral (delinquent behaviors) adjustment in high school, using a sample of Chinese American families, the largest ethnic group of Asian Americans (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). The current study is informed by two theoretical frameworks: the family stress model (Conger & Donnellan, 2007) and family systems theory (Cox & Paley, 2003), which will be discussed in detail below.

Extending the Family Stress Model to the Context of Parental Perceived Discrimination

Several studies have demonstrated a link between parental perceived discrimination and child adjustment (Anderson et al., 2014; Ford et al., 2013; Gassman-Pines, 2015; Gibbons et al., 2004). For example, Ford et al. (2013) revealed that parental experiences of discrimination were positively linked to adolescent depressive symptoms and negatively linked to adolescent psychological well-being. However, the mechanisms through which parental perceived discrimination relates to adolescent adjustment remain unspecified. One potential set of mechanisms may be family stress processes. According to the family stress model (Conger & Donnellan, 2007), family stressors may lead to greater parental emotional distress, which may in turn negatively affect parent–child interactions—either directly or indirectly through effects on marital interactions. Ultimately, parent–child interactions influence adolescent developmental outcomes. Parental perceived discrimination may act as one such family stressor (McNeil et al., 2014).

The family stress model has been widely supported in prior studies focusing on family economic stress (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994; Conger et al., 2002; Parke et al., 2004; Ponnet, 2014). For example, Conger et al. (1994) revealed that in White families, economic stress was concurrently related to parental depressive symptoms in early adolescence, which were longitudinally associated with marital conflict 1 year later. In turn, marital conflict was concurrently related to parental hostility toward adolescents, which was longitudinally linked to adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems 1 year later. Similar family stress processes have been found in Chinese American families as well. For example, Benner and Kim (2010) demonstrated that Chinese American parents’ economic pressure was associated with more parental depressive symptoms, which in turn were related to higher levels of hostility in marital interactions. Subsequently, both parental depressive symptoms and marital hostility were linked to more hostile parenting, which was related to more adolescent depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors.

The present study moves beyond previous studies using the family stress framework, in several ways. First, we consider parental discriminatory experiences as a family stressor that may influence Chinese American families above and beyond economic stress. Similar to economic stress, discriminatory experiences can increase depressive symptoms among Asian American adults, including Chinese Americans (Lee, 2003; Wei, Ku, Russell, Mallinckrodt, & Liao, 2008; Yip, Gee, & Takeuchi, 2008). Parental perceived discrimination has also been related to more conflict and aggression in the marital relationship and more conflictual parent–adolescent relationships (Riina & McHale, 2010). Moreover, a few studies on African American families have shown some initial evidence for the applicability of the family stress framework in understanding the effects of parental perceived discrimination (Anderson et al., 2014; Gibbons et al., 2004). These studies have demonstrated that parental perceived discrimination is concurrently associated with parental depressive symptoms, which longitudinally relate to the parent–child relationship and child outcomes.

Second, although many previous studies use a cross-sectional design (Benner & Kim, 2010; Ponnet, 2014), the current study uses a longitudinal design, which allows for better inferences around causal relationships as it provides a temporal order and enables researchers to examine relative change in outcomes by controlling for prior levels of outcomes (MacCallum & Austin, 2000). With adolescent outcomes at middle school being controlled for, we were able to conduct a conservative test of the study hypotheses by predicting relative change in adolescent outcomes from middle school to high school. Third, and most importantly, this study goes beyond prior literature using the family stress model by incorporating a family systems approach to examine both actor and partner effects as mediating family processes that may link family stress and adolescent outcomes.

A Family Systems Approach to Extending the Family Stress Model

Family systems theory proposes that the family is an interdependent dynamic system in which family members’ experiences are interrelated and can mutually influence each other (Cox & Paley, 2003). Several processes have been proposed to explain interdependence in a family, such as spillover and crossover effects (Erel & Burman, 1995). Spillover occurs when an individual brings experiences or feelings from one setting or relationship with another, at an intrapersonal level. For instance, a parent’s psychological distress from external stressors (e.g., discriminatory experiences or economic stress) may affect his or her interactions with their spouse and children (Anderson et al., 2014; Conger et al., 1994). Crossover refers to the transfer of experiences or affect between people on an interpersonal level. For example, one parent’s discriminatory experiences may relate to his or her spouse’s depressive symptoms, as couples may witness, share, and communicate about their experiences (Crouter, Davis, Updegraff, Delgado, & Fortner, 2006). Parents’ depressive symptoms may also be associated with their spouses’ interactions with them and their children (Ponnet, 2014). One way to examine spillover and crossover effects simultaneously is to utilize the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). In APIM, spillover and crossover effects are referred to as actor and partner effects, respectively.

Prior studies investigating the effects of parental stress (e.g., economic stress or discrimination) on family processes have mainly focused on actor effects—that is, the association between parents’ own stress and well-being and their relationships with family members—without taking into account the experiences of other family members (Anderson et al., 2014; Conger et al., 2002; Gibbons et al., 2004; Low & Stocker, 2005). However, emerging studies have begun to highlight the importance of considering both actor and partner effects (Crouter et al., 2006; Kenny et al., 2006; Ponnet, 2014; Ponnet, Van Leeuwen, Wouters, & Mortelmans, 2014). For example, a recent study examined how parents’ economic stress relates to their own and their spouses’ depressive symptoms, which in turn relate to their own and their spouses’ interactions with family members (e.g., marital conflict and parenting; Ponnet, 2014). In contrast to most studies, which have examined only the actor effects of parental depressive symptoms on marital relationships (Conger et al., 2002; Low & Stocker, 2005), Ponnet (2014) found not only significant actor effects but also significant partner effects of depressive symptoms on marital conflict. Researchers argue that to achieve a more accurate estimation of actor effects, it is important to take into account partner effects, even if they are not significant (Kenny et al., 2006; Ponnet, 2014; Ponnet et al., 2014).

Therefore, the current study integrates the APIM and the family stress model to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how family stressors influence family processes. By examining actor and partner effects simultaneously, this study may provide a more nuanced explanation of how parental perceived discrimination relates to adolescent outcomes via family processes.

Potential Parental Gender Differences

Including both mothers and fathers in the current study allowed us to examine potential differential effects of paternal and maternal perceived discrimination on adolescent adjustment. Fathers and mothers often differ in their childrearing roles (Chuang & Tamis-LeMonda, 2009; Palkovitz et al., 2014). Although fathers in the general U.S. population are becoming increasingly involved in childrearing, mothers in Chinese families are generally still the primary caregivers and are expected to be warm and supportive to their children (Li & Lamb, 2013). According to the fathering vulnerability hypothesis (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Raymond, 2004; Davies, Sturge-Apple, Woitach, & Cummings, 2009; Ponnet, 2014), fathers’ roles and responsibilities in child caregiving are less well defined by social conventions, which means that fathers may have less ability and a lower commitment to maintaining good relationships with their children, which may in turn place the father–child relationship at greater risk of being negatively influenced by external stress (e.g., economic or marital stress). Therefore, paternal perceived discrimination may have a stronger influence on adolescent adjustment than maternal perceived discrimination, given the potentially greater vulnerability of fathering under stress.

The Current Study

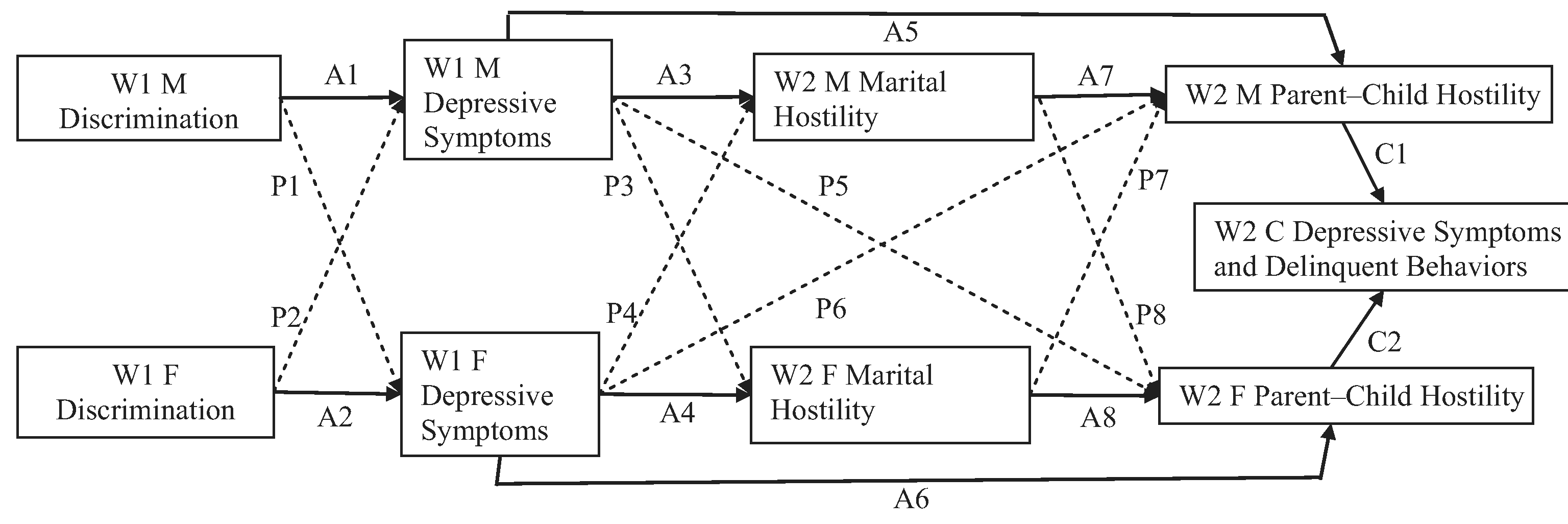

By incorporating the family stress model (Conger & Donnellan, 2007) and family systems theory (Cox & Paley, 2003), the present study aimed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms through which parental experiences of discrimination influence adolescent adjustment. The conceptual model is presented in Figure 1. We hypothesized that parental perceived discrimination would be indirectly related to adolescent outcomes (i.e., depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors) through multiple family processes involving both actor and partner effects. Specifically, we proposed that (a) parents’ discrimination experiences would be positively related to their own (actor effect, A1–A2 paths) and their spouses’ (partner effect, P1–P2 paths) depressive symptoms, (b) parental depressive symptoms would be positively related to hostility in their own (A3–A6 paths) and their spouses’ (P3–P6 paths) marital and parent–child interactions, (c) parents’ marital hostility would be associated with their own (A7–A8 paths) and their spouses’ (P7–P8 paths) parent–child hostility, and (d) parent–child hostility would be positively related to adolescents’ depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors (C1–C2 paths). In addition, we examined whether these hypothesized paths differ across mothers and fathers. Based on the fathering vulnerability hypothesis, we hypothesized that paternal perceived discrimination would have stronger indirect effects on adolescent adjustment than maternal perceived discrimination.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model linking parental perceived discrimination, parental depressive symptoms, marital hostility, parent–child hostility, and adolescent adjustment. A paths (bolded solid lines) are actor effects, P paths (dotted lines) are partner effects, and C paths (solid lines) are effects of family interactions on adolescent outcomes. W1 = Wave 1, W2 = Wave 2, M = Mother, F = Father, C = Child. Covariance or residual covariance of each variable between actor and partner within each time point were also specified but are not shown for figure clarity.

Method

Participants

This study used Wave 1 and Wave 2 data from a longitudinal study of 444 Chinese American families, with data collected 4 years apart. Adolescents were initially recruited when they were in middle school (seventh or eighth grade). At Wave 1, they ranged in age from 12 to 15 years (M = 13.03, SD = 0.73); mothers’ ages ranged from 31 to 56 years (M = 44.08, SD = 4.52); fathers’ ages ranged from 36 to 79 years (M = 47.93, SD = 6.15). Slightly over half (54%) of the adolescent sample is female. Three hundred and fifty families participated in Wave 2. Median and average family income was between $30,001 and $45,000 at Wave 1 and was between $45,001 and $60,000 at Wave 2. Median and average parental education level was a high school degree, across both waves. Most of the adolescents (75%) were born in the United States, whereas a majority of parents (91% of the mothers and 88% of the fathers) were born outside the United States. Most of the participating families hailed from Hong Kong or southern provinces of China; fewer than 10 families originally came from Taiwan. Most of the fathers (84% at Wave 1 and 83% at Wave 2) and mothers (77% at Wave 1 and 82% at Wave 2) were employed at least part time. Parents’ occupations ranged from unskilled laborer (e.g., construction worker, janitor) to professional (e.g., banker, computer programmer). The majority of the sample speak Cantonese as their home language, < 10% of the families speak Mandarin.

Procedure

Participants were initially recruited in 2002 from seven middle schools in major metropolitan areas of Northern California. With the aid of school administrators, Chinese American students were identified. All eligible families were sent a letter describing the research project in both English and Chinese (traditional and simplified). Forty-seven percent of these families that returned parent consent and adolescent assent received a packet of questionnaires for the mother, father, and target adolescent in the household. Participants were instructed to complete the questionnaires alone and not to discuss their answers with others. They were also instructed to seal their questionnaires in the provided envelopes immediately after they completed the questionnaires. Within approximately 2–3 weeks after sending the questionnaire packet, research assistants visited each school to collect the completed questionnaires during the students’ lunch periods. Among the families who agreed to participate, 76% returned surveys. Four years after the initial wave, families were asked to participate in the second wave. Families who returned questionnaires were compensated a nominal amount of money ($30 at Wave 1 and $50 at Wave 2) for their participation.

Questionnaires were prepared in English and Chinese (traditional and simplified). The questionnaires were first translated to Chinese and then back translated to English. The majority of parents (over 70%) used the Chinese language version of the questionnaire, and the majority (over 80%) of adolescents used the English version.

The attrition rate from Wave 1 to Wave 2 was 21%. Attrition analyses were conducted at Wave 2 to compare families who participated with those who had dropped out on the demographic characteristics and central study variables measured at Wave 1 (i.e., adolescent age, gender, nativity, depressive symptoms, and delinquent behaviors; parent age, nativity, education level, economic stress, perceived discrimination, and depressive symptoms; and family income). Only two significant differences emerged: Boys were less likely than girls to have continued participating, χ2(1) = 12.66, p < .001, and foreign-born fathers were less likely than U.S.-born fathers to have continued participating, χ2(1) = 4.16, p < .05.

Measures

Perceived Discrimination

Parents’ perceived discrimination was measured by the chronic daily discrimination scale (Kessler et al., 1999). One item specifically relevant to Asian Americans, “People assume my English is poor,” was added to the original nine-item scale (e.g., “I am treated with less courtesy than other people”). The 10-item scale has been validated for Chinese American samples in previous studies (Benner & Kim, 2009b; Hou et al., 2015). At Wave 1, mothers and fathers self-reported on a scale ranging from 1 = never to 4 = often, with a higher score indicating more experiences of being the target of discrimination (α = .86 for mothers, α = .87 for fathers).

Depressive Symptoms

Parents’ and adolescents’ depressive symptoms were measured by the widely used 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). Parental depressive symptoms were assessed at Wave 1. Adolescent depressive symptoms were measured at both Wave 1 and Wave 2. Fathers, mothers, and adolescents self-reported how often during the past week they had experienced the depressive symptoms described, with items such as “Bothered by things usually not bothered by” and “Could not shake off the blues (feeling down or bad) even with help from family or friends,” on a scale of 0 = rarely or none of the time to 3 = most or all of the time. Higher mean scores reflected more depressive symptoms (αs = .87–.90 across waves and informants).

Family Interactions

Hostility in family interactions was measured at Wave 2, using seven items adapted from Conger et al. (2002). These items assess participants’ engagement in behaviors toward family members, such as engaging in criticism, fighting, or arguing. Sample items are, “Shout or yell at him or her because you were mad at him or her” and “Criticize him or her or his or her ideas.” For marital hostility, fathers and mothers self-reported how often they engaged in these behaviors in their marital interactions (i.e., their own hostility toward spouses). For mother–child hostility and father-child hostility, adolescents reported how often their mothers and fathers engaged in these behaviors toward them (i.e., mother and father hostility toward children). A rating scale ranging from 1 = never to 7 = always was used for all reporters. Higher mean scores indicate higher hostility (αs = .79 and .83 for mothers’ and fathers’ hostility toward spouses, respectively; αs = .87 for parent-child hostility).

Delinquent Behaviors

Adolescents’ delinquent behaviors at Waves 1 and 2 were measured with items adapted from the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and included items such as stealing, running away, and lying. Adolescents reported the extent to which the listed behaviors applied to them during the past 6 months, on a scale ranging from 0 = not at all true to 2 = often true or very true, with higher mean scores reflecting more delinquent behaviors (α = .60 and .71 for Waves 1 and 2, respectively).

Covariates

The current study considered several important covariates. First, given that parental education level and economic stress have been widely associated with family processes and child outcomes (Conger et al., 2002; Parke et al., 2004; Ponnet, 2014), the current study included them as covariates on all endogenous variables. For parental education level, on a scale of 1 = no formal schooling to 9 = finished graduate degree, parents reported on their highest education level. Parent economic stress was measured with two items: “Think back over the past 3 months. How much difficulty did you have with paying your bills?,” with responses ranging from 1 = none at all to 5 = a great deal; and “Think back over the past 3 months. Generally, at the end of each month, how much money did you end up with?,” with ratings ranging from 1 = more than enough to 5 = very short. These items have been validated in previous studies of Chinese American families (Mistry, Benner, Tan, & Kim, 2009). Mean scores of these two items were taken, with higher scores reflecting higher economic stress (α = .78 and .70 for mothers and fathers, respectively).

Second, because ethnic–racial socialization (i.e., preparation for bias) has often been linked to child outcomes in ethnic minority families (Hughes et al., 2006; McHale et al., 2006), we included it as a covariate on adolescent outcomes. Parental ethnic–racial socialization was measured at Wave 2 by four items adapted from Hughes and Johnson’s (2001) measure of ethnic–racial socialization behaviors. These items focus on parents’ socialization practices around preparing their children for racial bias (e.g., “talks to me about the possibility that some people might treat me badly or unfairly because I am Chinese”). The four-item scale has been previously validated in a study on Chinese Americans (Benner & Kim, 2009b). Adolescents reported on a 3-point scale from 1 = seldom to 3 = often, with higher mean scores indicating a greater degree of ethnic–racial socialization by parents (α = .80 and .79 for mothers and fathers, respectively).

Third, parent age and nativity (i.e., whether born in the U.S. or not) were included as covariates on all endogenous variables given their potential associations (Yip et al., 2008). Fourth, adolescent age, gender, and nativity were included as covariates on parent–child interaction and adolescent outcomes, given their associations demonstrated in prior studies (Kwak, 2003).

Analysis Plan

Data analyses were conducted in three steps. First, we conducted correlational analyses to describe the bivariate associations between study variables. Second, adopting the structural equation framework, we tested the conceptual model shown in Figure 1, including the indirect effects from parental perceived discrimination at Wave 1 to children’s adjustment at Wave 2. In this model, actor effects (A paths) and partner effects (P paths) between parents and parents’ influence on children (C paths) were estimated simultaneously. To account for within-family dependence, covariance or residual covariance of each variable between mother and father reports within each time point were also specified but are not shown for figure clarity. Third, to test whether the paths differ across parental gender, we conducted invariance tests using Wald tests of parameter constraints to compare all the modeled pathways across parental gender. All path models were conducted with Mplus 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). Mplus uses the full information maximum likelihood estimation method to handle missing data, which enables full usage of all available data in the path analyses. To address nonnormality of variables (i.e., depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors) in the model, maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used for all models. In path analyses, both direct and indirect effects are estimated simultaneously. Inferences for the indirect effects were estimated using bootstrapping (Muthén& Muthén, 1998–2015).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among study variables. Observation of the bivariate correlations showed preliminary evidence for the conceptual model (Figure 1). Results demonstrated that (a) parents’ discriminatory experiences were positively correlated with their own (A1–A2 paths) and their spouses’ depressive symptoms (P1–P2 paths) at Wave 1, (b) parental depressive symptoms at Wave 1 were positively correlated with their own hostility in marital interactions at Wave 2 (A3–A4 paths), (c) paternal depressive symptoms at Wave 1 were positively correlated with paternal (A6 path) and maternal (P6 path) hostility toward children at Wave 2, and (d) maternal and paternal hostility toward children were positively correlated with adolescent depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors at Wave 2 (C1–C2 paths). Moreover, there was a moderate positive association between mothers’ and fathers’ reports on the same construct (e.g., maternal and paternal depressive symptoms). In addition, there was moderate stability of adolescent depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors from Wave 1 to Wave 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of the Studied Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. W1 M Disc | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2. W1 F Disc | .30*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3. W1 M Depr | .35*** | .18*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4. W1 F Depr | .20*** | .36*** | .44*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5. W2 M–F Hstl | .14* | −.01 | .22*** | .08 | 1.00 | |||||

| 6. W2 F–M Hstl | −.07 | .07 | .02 | .14* | .38*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 7. W2 M–C Hstl | .07 | .08 | .07 | .19*** | .10 | .05 | 1.00 | |||

| 8. W2 F–C Hstl | .02 | .10 | −.01 | .14* | .11 | .06 | .63*** | 1.00 | ||

| 9. W2 C Depr | .05 | .03 | .08 | .14* | .06 | .02 | .36*** | .26*** | 1.00 | |

| 10. W2 C Delq | .11* | −.03 | .06 | .05 | .03 | .02 | .24*** | .13* | .26*** | 1.00 |

| 11. W1 C Depr | .15** | .03 | .18*** | .15** | .08 | −.04 | .19*** | .13* | .34*** | .29*** |

| 12. W1 C Delq | .08 | .03 | .05 | .02 | .03 | −.03 | .16** | .08 | .05 | .36*** |

| 13. W1 M economic stress | .14** | .09 | .38*** | .24*** | .07 | −.10 | .01 | −.06 | .01 | −.05 |

| 14. W1 F economic stress | .11* | .17** | .29*** | .41*** | .07 | .01 | .04 | .04 | .03 | .04 |

| 15. W1 M education | −.09 | −.05 | .28*** | .22*** | −.02 | .01 | .13* | .06 | −.05 | .00 |

| 16. W1 F education | −.07 | −.10 | −.21*** | .28*** | .03 | −.05 | −.04 | −.03 | −.14* | .02 – |

| 17. W2 M racial socialization | .18** | .09 | .09 | .14* | .10 | .00 | .09 | .14* | .15** | .18*** |

| 18. W2 F racial socialization | .11 | .07 | .04 | .06 | .04 | .00 | .04 | .16** | .11 | .13* |

| 19. W1 M age | .01 | −.02 | .01 | −.05 | −.08 | −.02 | −.02 | −.05 | −.02 | .03 |

| 20. W1 F age | −.03 | .02 | .10 | .12* | −.05 | −.04 | .08 | .02 | .08 | −.02 |

| 21. W1 C age | .01 | −.05 | .06 | .07 | .10 | .02 | .05 | .03 | .09 | .07 |

| 22. W1 M born | .10* | .09 | .20*** | .18** | .08 | .08 | .06 | .02 | .06 | −.03 |

| 23. W1 F born | −.01 | .05 | .17** | .14** | .05 | .07 | −.03 | −.03 | −.01 | −.08 |

| 24. W1 C born | −.06 | −.13* | .10* | .05 | .09 | .12* | −.04 | −.02 | .02 | −.05 |

| 25. W1 C sex | .01 | .10 | .08 | .08 | .00 | −.08 | −.01 | −.05 | .10 | −.11* |

| M | 1.96 | 2.02 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 2.61 | 2.51 | 2.99 | 2.74 | 0.71 | 0.23 |

| SD | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 1.16 | 1.15 | 0.46 | 0.23 |

| N | 407 | 381 | 407 | 380 | 267 | 262 | 340 | 323 | 348 | 344 |

Note. N = number of valid cases; W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; M = Mother; F = Father; C = Children; Disc = discrimination; Depr = depressive symptoms; Hstl = hostility; Delq = delinquent behaviors.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Path Analysis

To examine the direct and indirect relations among focal variables, we first tested the conceptual model, shown in Figure 1, with Wave 1 adolescent outcomes as covariates predicting Wave 2 adolescent outcomes. The model fit for this basic model was good, χ2(32) = 44.319, p = .072, comparative fit index (CFI) = .976, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .029 [.000, .049], standard root mean-square residual (SRMR) = .043.

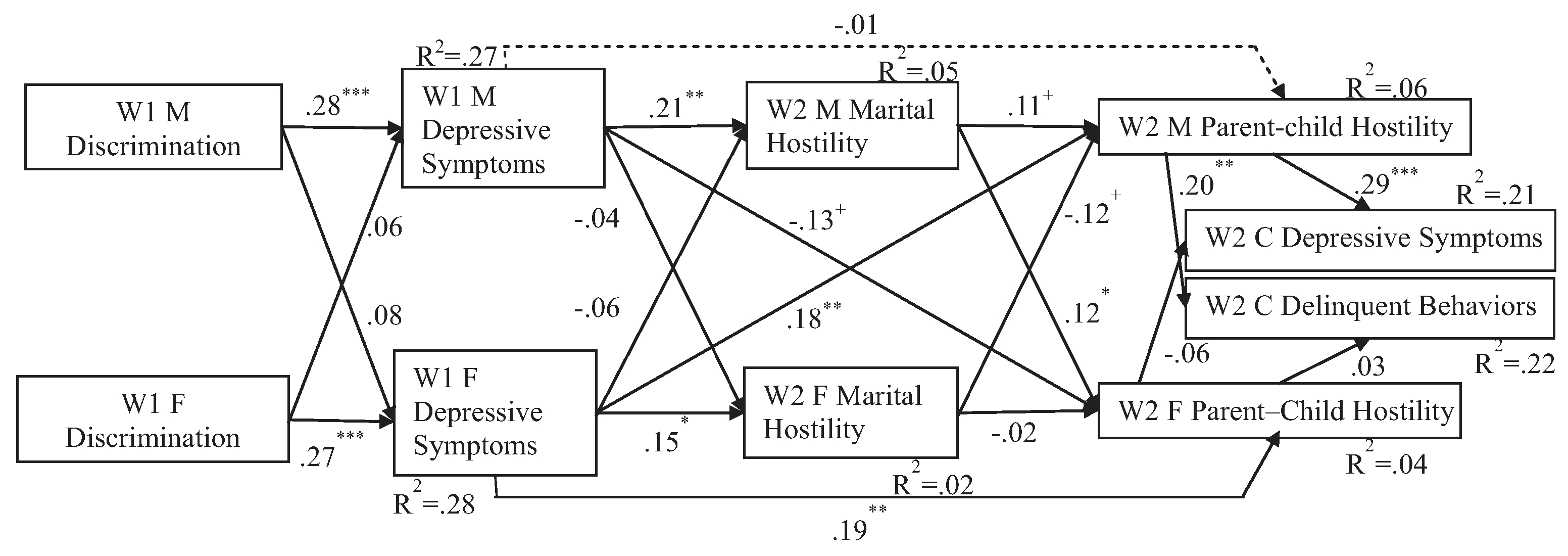

Then, we introduced covariates, and the model fit remained good, χ2(84) = 115.618, p = .013, CFI = .953, RMSEA= .029[.014,.041], SRMR = .033. Path parameters for the focal paths showed a consistent pattern across the two models. Thus, standardized path parameters for the final model, with all covariates, are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Linking Wave 1 parental perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, Wave 2 marital hostility, parent–child hostility, and adolescent depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors.

Note. Model fit is good, χ2(84) = 115.618, p = .013, comparative fit index = .953, root mean square error of approximation = .029 [.014, .041], SRMR = .033. Solid lines represent significant paths. Dotted lines represent nonsignificant paths. Bold lines represent the significant indirect pathway linking parental perceived discrimination and adolescent adjustment. W1 = Wave 1, W2 = Wave 2, M = Mother, F = Father, C = Child. The model controlled for the following covariates: adolescent adjustment at Wave 1; adolescent age, gender, and nativity; parental age, nativity, economic stress, educational level, and ethnic–racial socialization practices. +p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Direct Links

Results showed partial support for the actor and partner effects we proposed (see Figure 2). For the link between parental perceived discrimination and parental depressive symptoms, we found significant actor effects but no partner effects: Parents’ perceived discrimination was positively linked to their own but not their spouses’ depressive symptoms at Wave 1. Regarding the association between parental depressive symptoms and marital hostility, we found significant actor effects but no partner effects: Parental depressive symptoms at Wave 1 were positively related to their own hostility toward their spouses but not their spouses’ hostility toward them at Wave 2. With respect to the relation between parental depressive symptoms and parent–child hostility, we found both actor and partner effects: Fathers’ (but not mothers’) depressive symptoms at Wave 1 were positively linked to their own and their spouses’ hostility toward their children at Wave 2. As for the relation between marital hostility and parent–child hostility at Wave 2, we found only a partner effect: When mothers reported greater hostility toward fathers, fathers reported greater hostility toward children. Finally, regarding the relation between parent–child hostility and adolescent outcomes, we found that maternal (but not paternal) hostility toward children was positively linked to adolescent depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors at Wave 2.

Indirect Effects

All potential indirect pathways from Wave 1 parental perceived discrimination to Wave 2 adolescent outcomes in the conceptual model were tested. Only one significant indirect pathway was identified: Wave 1 paternal perceived discrimination to Wave 1 paternal depressive symptoms to Wave 2 maternal hostility toward children to Wave 2 adolescent depressive symptoms, β = .015, SE = .007, p = .032, 95% CI [.003, .026], and delinquent behaviors, β = .010, SE = .006, p = .073, 95% CI [.001, .019].

Invariance Across Mothers and Fathers

Wald tests of parameter constraints were used to compare pathways in the conceptual model across parental gender. The paths were compared in three steps. First, all actor effects (A paths) were compared across mothers and fathers. No parental gender differences were found, W(4) = 4.593, p = .332. Second, all the partner effects (P paths) were compared. Significant parental gender differences were found, W(4) = 9.658, p = .047. Thus, we further tested each partner path to identify the source of difference. Results demonstrated that partner effects between depressive symptoms and parent–child hostility (P5 and P6 paths in Figure 1) differed significantly across parental gender, W(1) = 8.377, p = .004. Although the link between paternal depressive symptoms and maternal hostility toward children was positive and significant (β = .185, SE = .062, p = .003), the link between maternal depressive symptoms and paternal hostility toward children was negative and only marginally significant (β = .125, SE = .067, p = .062). Third, we compared the links between parent–child hostility and adolescent adjustment (C paths). We found marginally significant results, W(2) = 5.559, p = .062, indicating that maternal hostility may have a stronger negative effect on adolescent adjustment (β = .293, SE = .077, p = .000 for depressive symptoms and β = .203, SE = .074, p = .006 for delinquent behaviors) compared to paternal hostility (β = .035, SE = .075, p = .637 for depressive symptoms and β = −.057, SE = .068, p = .400 for delinquent behaviors).

Discussion

Despite past research suggesting links between parental discriminatory experiences and child adjustment (Anderson et al., 2014; Ford et al., 2013; Gassman-Pines, 2015; Gibbons et al., 2004), there is a dearth of studies examining mechanisms through which parental discriminatory experiences may relate to adolescent adjustment. The current study provided a comprehensive investigation of several such mechanisms by including multiple informants to assess mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms and marital and parent–child hostility as potential mediators. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that has simultaneously tested actor and partner effects in family processes linking parental perceived discrimination and adolescent adjustment. Consistent with the family stress model (Conger & Donnellan, 2007) and family systems theory (Cox & Paley, 2003), we found an indirect effect from parental perceived discrimination to adolescent adjustment through family processes involving both actor and partner effects. We also demonstrated parent gender differences in the mediating pathways.

Linking Parental Perceived Discrimination and Adolescent Adjustment

The family stress model has been shown to be a very useful theoretical framework for understanding the effects of family economic stress on child outcomes (Conger et al., 1994, 2002; Low & Stocker, 2005). The present study extended this body of literature by applying the family stress model to the context of parental perceived discrimination and adolescent adjustment. Our results suggest that parental discriminatory experiences can function as a family stressor that influence adolescent adjustment through family processes, as suggested by the family stress model. Parental experiences of discrimination have unique implications for Chinese American families, above and beyond the effect of family economic stress. Specifically, we found that parental perceived discrimination was associated with more parental depressive symptoms, which were positively related to marital and parent–child hostility. Subsequently, parent-child hostility was linked to more adolescent depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors. These findings extend the family stress model by focusing on perceived discrimination as a key stressor in Chinese American families.

Most importantly, the current study moved beyond previous research by considering the interdependence of mothers and fathers and examining both actor and partner effects in family processes. The moderate bivariate associations between mothers and fathers within construct (e.g., maternal and paternal depressive symptoms) support the importance of taking into account the interdependence of mothers and fathers. The bivariate intrapersonal and interpersonal correlations between the study constructs indicate the benefits of considering both actor and partner effects. By simultaneously testing actor and partner effects, we were able to demonstrate whether they have unique effect above and beyond each other. Specifically, we found that parents’ perceived discrimination related to their own (but not their spouses’) depressive symptoms, which in turn related to their own (but not their spouses’) marital hostility. These results support previous studies demonstrating the effect of parents’ stress on their own psychological well-being and marital interactions (Conger et al., 1994, 2002; Low & Stocker, 2005). The more prominent actor effects in these relations are consistent with the widely held assumptions that one’ emotions and behaviors are most likely to be affected by their own experiences versus those of others such as spouses (Conger et al., 1994, 2002; Low & Stocker, 2005).

However, for antecedents of parent–child hostility, in addition to actor effects, we also found significant partner effects. Generally, this is probably because parenting is a shared responsibility of both parents, which requires cooperation and support from partners (Teubert & Pinquart, 2010). Specifically, in the association between parental depressive symptoms and parent–child hostility, we found both actor and partner effects. These results indicate that parents’ interactions with children depend not only on their own depressive symptoms, but also on their spouses’ depressive symptoms. These results are consistent with recent findings linking participants’ parenting stress to their own and their spouses’ problems in parent–child communication (Ponnet et al., 2014). Moreover, in the relation between marital and parent–child hostility, we found a marginally significant spillover (i.e., actor) effect and a significant crossover (i.e., partner) effect. These results are slightly inconsistent with prior studies demonstrating a significant spillover effect from marital conflict or hostility to hostile behaviors toward children (Benner & Kim, 2010; Conger et al., 1994). This may be because, unlike the current study, prior studies did not control for crossover effects while examining spillover effects. Our results suggest that parents’ marital hostility seems to relate to both their own and their partners’ hostility toward their adolescent children, but when examined simultaneously, crossover effects appear to be more evident. Moreover, there seems to be parent gender differences in these partner effects, which are discussed in detail in the following section.

The most intriguing finding is the significant indirect pathway from paternal perceived discrimination to paternal depressive symptoms (actor effect) to maternal hostility toward adolescents (partner effect) to adolescent adjustment. This result is consistent with a previous finding that paternal risk factors (e.g., poverty and depressive symptoms) were indirectly linked to children’s outcomes (i.e., cognition and social behaviors) only through maternal supportiveness to children (Cabrera, Fagan, Wight, & Schadler, 2011). The fact that significant pathways involved both actor and partner effects is important, given that numerous studies demonstrating mediating family processes from family stressors to child outcomes have focused on actor effects only (Anderson et al., 2014; Conger et al., 2002; Gibbons et al., 2004; Low & Stocker, 2005). In marital relationships, one partner’s emotions and behaviors depend on those of the other partner (Cox & Paley, 2003), which means that biased estimation may occur when only actor effects are examined in family processes and when mothers and fathers are treated only as independent individuals (Kenny et al., 2006). Overall, the current findings support the family systems approach, which highlights the idea that the family is a complex, integrated whole and that family members can mutually influence each other (Cox & Paley, 2003). Our findings also indicate that the ways in which parents influence each other differ for mothers and fathers, given observed variation in crossover effects by parent gender.

Parent Gender Differences

Adopting the APIM also allowed us to provide a more nuanced picture of gender differences in the different indirect pathways from paternal and maternal perceived discrimination to adolescent adjustment. First and foremost, consistent with our hypothesis, we found indirect effects from parental perceived discrimination to adolescent adjustment only for fathers (not mothers). This finding is generally in accordance with previous studies demonstrating that the father–child (but not mother–child) acculturation gap was indirectly related to adolescent outcomes through family processes (Kim, Chen, Wang, Shen, & Orozco-Lapray, 2013; Schofield, Parke, Kim, & Coltrane, 2008). The seemly greater influence of paternal discriminatory experiences on adolescent depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors may be attributed to the role played by fathers in Chinese American families. Paternal experiences may have more important implications for the family because fathers tend to be more involved in American culture than mothers (Kim, Gonzales, Stroh, & Wang, 2006) and are generally more responsible for socializing children into the outside world (Paquette, 2004). However, as the current study examined the indirect effects from parental perceived discrimination to adolescent adjustment only through family stress processes, it is possible that maternal perceived discrimination may exhibit greater indirect effects on adolescent adjustment through other mediating processes. For example, as mothers may play a more important role in ethnic–racial socialization (Hughes et al., 2006), potential indirect effects of parental perceived discrimination on child outcomes through ethnic-racial socialization may be more robust for mother-child dyads.

Second, we found significant gender differences in the partner effects of parents’ depressive symptoms on spouses’ hostility toward children. Although the association between paternal depressive symptoms and maternal hostility toward children was positive and significant, the link between maternal depressive symptoms and paternal hostility toward children was negative, although only marginally significant. This finding indicates that spouses’ emotional problems may be more detrimental for mother–child interactions than for father–child interactions. There are several potential reasons for such a difference. First, mothers may be more aware of and concerned about fathers’ depressive symptoms, as studies have shown that women are more sensitive to others’ emotions (Davis, 1983; Montagne, Kessels, Frigerio, de Haan, & Perrett, 2005). Second, women may rely more on emotional support in close relationships (Burleson, 2003). Hence, when fathers are less able to provide emotional support due to their depressive symptoms, mothers’ interactions with children may be more likely to be negatively affected. In contrast, when mothers exhibit more depressive symptoms, their traditional role as a provider of warmth and support may be compromised. In that case, fathers may feel the need to compensate for the loss of maternal warmth and support, such that they may be less hostile to their children. Future studies are needed to investigate these potential mechanisms.

Third, the partner effects of marital hostility on parent–child hostility were significant only for father–child (but not mother–child) hostility. That is, when fathers experienced more hostility from mothers, they were more likely to interact with adolescents in more hostile ways. This result is consistent with prior studies demonstrating that father–child relationships are more vulnerable to marital conflict (Cummings et al., 2004; Davies et al., 2009). This is potentially due, in part, to the fact that fathers may have a lower commitment to maintaining good relationships with their children, given that their role of parenting is less well-defined by social conventions (Cummings et al., 2004). Therefore, often as the secondary caregiver, fathers’ relationships with children may rely more on how their spouses (the primary caregiver) treat them (i.e., fathers).

The link between parent–child hostility and adolescent outcomes also appears to be different across mother–child and father–child dyads. Only maternal (not paternal) hostility toward children was related to adolescent adjustment, although the difference between the strengths of these associations was only marginally significant. This finding suggests that maternal (vs. paternal) hostility may be more detrimental for adolescent development, perhaps because maternal hostility contrasts with adolescents’ expectations of maternal parenting, given that mothers are usually expected to be caring and warm (Berndt, Cheung, Lau, Hau, & Lew, 1993; Chuang & Tamis-LeMonda, 2009). As fathers usually play a more authoritarian role in Chinese American families (Berndt et al., 1993; Kim et al., 2013), adolescents may be more tolerant of hostility from fathers.

Taken together, the present study’s findings suggest that parents’ experiences of discriminatory treatment seem to have significant implications for child development in Chinese American families. As far as we know, this is the first study linking parental perceived discrimination to adolescent adjustment in Chinese American families or Asian American families. Discriminatory experiences are relatively underexplored among Asian Americans compared to other ethnic minority groups such as African Americans. This is especially true when it comes to studies on parental experiences of discrimination and child adjustment. The insufficient attention to discriminatory experiences and their implications for Asian American families may be related to the widespread “model minority” stereotype about Asian Americans (Xia et al., 2013). The extant studies on Asian Americans’ discriminatory experiences indicate that Asian Americans are not exempt from the negative effects of discrimination and reveal an association between individuals’ discriminatory experiences and adjustment (Benner & Kim, 2009a; Grossman & Liang, 2008; Hou et al., 2015). The current study moved beyond these individual-level analyses of the effects of perceived discrimination by taking a family systems view to demonstrate how parents’ perceived discrimination may affect other family members. Consistent with prior findings on African American families (Anderson et al., 2014; Ford et al., 2013; Gibbons et al., 2004; McNeil et al., 2014), this study suggests that parental perceived discrimination has significant implications for Chinese American families as well.

Our findings can inform professionals who work with Chinese American families about the implications of parental discriminatory experiences on multiple family processes that ultimately relate to adolescent adjustment. Professionals should consider the detrimental effects of discrimination and work not only to reduce discrimination but also to empower Chinese American parents to cope with discrimination. Improving family interactions (e.g., by reducing hostility) may be a useful intervention strategy for reducing the negative effects of parental perceived discrimination on adolescent adjustment. Although only paternal perceived discrimination was indirectly related to adolescent adjustment, effective interventions should aim to alleviate the detrimental effect of parental discriminatory experiences for both mothers and fathers, given the ways in which they influence each other in the family context.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is among the first to demonstrate indirect links between parental perceived discrimination and adolescent adjustment. In particular, this study contributes to the current body of literature by exploring family stress pathways involving intrapersonal and interpersonal effects, and by using rigorous methods to examine these family stress processes. The first advantage of this study is that it used mothers’ and fathers’ self-reports of their own discriminatory experiences, depressive symptoms, and spousal hostility, along with adolescents’ reports of parent–child interactions and adjustment measures; this method reduces the problem of common-method variance. Second, compared to previous cross-sectional studies, the current study’s longitudinal design provides better inference for the influence of parental perceived discrimination on adolescent adjustment and the mediation pathways. Third, incorporating the APIM enabled us to explore actor and partner pathways and to test for parent gender differences. Moreover, we controlled for a range of important covariates, including family socioeconomic factors and ethnic-racial socialization practices.

Despite these strengths, it is important to note some limitations when considering the current study’s implications. First, our study focuses on Chinese American families, and Asian American cultures are not homogeneous (Xia et al., 2013); whether our findings can be replicated in other Asian American samples should be tested in future studies. Second, the generalizability of our findings to other Chinese American samples also needs to be tested. Our participants come from Northern California, an area with a large population of Chinese Americans, and ethnically concentrated neighborhoods may protect ethnic minorities from discrimination (White, Zeiders, Knight, Roosa, & Tein, 2014). Therefore, future studies involving participants from communities with lower levels of ethnic concentration may find even stronger effects of parental perceived discrimination on Chinese American families. In a similar vein, most of the parents in our study originally came from South China and speak Cantonese as their native language. However, there are Chinese Americans who hail from Taiwan or other parts of China, where Mandarin is spoken. Different parts of China have distinct subcultures, and their family processes may not necessarily be the same. For example, studies have found that parents in South China (e.g., Hong Kong) are more authoritarian than parents in North China (e.g., Beijing) and Taiwan (Berndt et al., 1993; Lai, Zhang, & Wang, 2000). In more authoritarian families, parental stress may relate to more hostility in family interactions. Hence, future studies that include Chinese American samples from different cultural backgrounds may find variations in how parental perceived discrimination relates to family processes.

Third, factors such as generational status may moderate the association between perceived discrimination and individual adjustment (Yip et al., 2008). However, our data do not allow us to test this possibility, because we had a small number of second-generation parents. Future studies could include samples with a more even distribution of first-, second-, and third-generation individuals to examine the extent to which our results may vary across parental generational status. Fourth, this study relied on self-reported measures. Future studies should replicate our findings using more objective methods, such as third-party evaluations of depressive symptoms, delinquent behaviors, and family interactions.

Finally, this is a correlational study, and we cannot ascertain causal relationships. Although we used two waves of longitudinal data to test temporal relations (a method that provides additional support for the ordering of model constructs), some relations were still examined concurrently. For example, both parental perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms were assessed at Wave 1. Although we proposed that perceived discrimination related to more depressive symptoms based on prior empirical work (Lee, 2003; Wei et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2008), our study cannot rule out the possibility that more depressed parents may be more likely to perceive discrimination (Hou et al., 2015). Also, both marital hostility and parental–child hostility were assessed at Wave 2. Although we proposed that marital hostility would lead to more parent–child hostility based on the family stress model (Conger & Donnellan, 2007), our study cannot rule out the possibility that parent–child hostility may also increase marital hostility (Cox & Paley, 2003). Future studies should further investigate the directionality (and potentially bidirectionality) of the relations among the central constructs of interest.

Despite these limitations, this study made significant contributions to the literature by integrating the family stress model and family systems theory to investigate indirect links between parental perceived discrimination and adolescent adjustment. We found that paternal perceived discrimination was indirectly related to adolescent adjustment through an actor effect on paternal depressive symptoms and a partner effect of paternal depressive symptoms on mothers’ hostility toward adolescents. Our results underscore the importance of considering the family as an interdependent dynamic system and including multiple family members in studies on family stress processes. By investigating the implications of parental perceived discrimination on Asian American families, a topic that has been understudied, this study provides a more comprehensive view of child development in ethnic minority families.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided through awards to Su Yeong Kim from (a) Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD 5R03HD051629–02, (b) Office of the Vice President for Research Grant/Special Research Grant from the University of Texas at Austin, (c) Jacobs Foundation Young Investigator Grant, (d) American Psychological Association Office of Ethnic Minority Affairs, Promoting Psychological Research and Training on Health Disparities Issues at Ethnic Minority Serving Institutions Grant, (e) American Psychological Foundation/Council of Graduate Departments of Psychology, Ruth G. and Joseph D. Matarazzo Grant, (f) California Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Extended Education Fund, (g) American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Massachusetts Avenue Building Assets Fund, and (h) Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD 5R24HD042849–14 grant awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla L (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Hussain SB, Wilson MN, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, & Williams JL (2014). Pathways to pain: Racial discrimination and relations between parental functioning and child psychosocial well-being. Journal of Black Psychology, 41, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/0095798414548511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Kim SY (2009a). Experiences of discrimination among Chinese American adolescents and the consequences for socioemotional and academic development. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1682–1694. doi: 10.1037/a0016119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Kim SY (2009b). Intergenerational experiences of discrimination in Chinese American families: Influences of socialization and stress. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 862–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00640.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Kim SY (2010). Understanding Chinese American adolescents’ developmental outcomes: Insights from the family stress model. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00629.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Cheung PC, Lau S, Hau K-T, & Lew WJF (1993). Perceptions of parenting in mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong: Sex differences and societal differences. Developmental Psychology, 29, 156–164. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson BR (2003). The experience and effects of emotional support: What the study of cultural and gender differences can tell us about close relationships, emotion, and interpersonal communication. Personal Relationships, 10, 1–23. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Fagan J, Wight V, & Schadler C (2011). Influence of mother, father, and child risk on parenting and children’s cognitive and social behaviors. Child Development, 82, 1985–2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01667.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SS, & Tamis-LeMonda C (2009). Gender roles in immigrant families: Parenting views, practices, and child development. Sex Roles, 60, 451–455. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9601-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, & Donnellan MB (2007). An interaction-ist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, & Simons RL (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65, 541–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, & Brody GH (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38, 179–193. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, & Paley B (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 193–196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Davis KD, Updegraff K, Delgado M, & Fortner M (2006). Mexican American fathers’ occupational conditions: Links to family members’ psychological adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 843–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00299.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, & Raymond J (2004). Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict In Lamb ME (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (4th ed., pp. 196–221). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Woitach MJ, & Cummings EM (2009). A process analysis of the transmission of distress from interparental conflict to parenting: Adult relationship security as an explanatory mechanism. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1761–1773. doi: 10.1037/a0016426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113–126. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, & Burman B (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent–child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford KR, Hurd NM, Jagers RJ, & Sellers RM (2013). Caregiver experiences of discrimination and African American adolescents’ psychological health over time. Child Development, 84, 485–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01864.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, & McAdoo HP (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01834.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassman-Pines A (2015). Effects of Mexican immigrant parents’ daily workplace discrimination on child behavior and family functioning. Child Development, 86, 1175–1190. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, & Brody G (2004). Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman JM, & Liang B (2008). Discrimination distress among Chinese American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37,1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9215-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Kim S, Wang Y, Shen Y, & Orozco-Lapray D (2015). Longitudinal reciprocal relationships between discrimination and ethnic affect or depressive symptoms among Chinese American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 2110–2121. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0300-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, & Johnson D (2001). Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 981–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00981.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 747. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian TW, McKenry PC, & McKelvey MW (1994). Cultural variations in parenting: Perceptions of Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, and Asian-American parents. Family Relations, 43, 30–37. doi: 10.2307/585139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). The measurement of nonindependence In Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (Eds.), Dyadic data analysis (pp. 25–52). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, & Williams DR (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 208–230. doi: 10.2307/2676349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Chen Q, Wang Y, Shen Y, & Orozco-Lapray D (2013). Longitudinal linkages among parent–child acculturation discrepancy, parenting, parent-child sense of alienation, and adolescent adjustment in Chinese immigrant families. Developmental Psychology, 49, 900–912. doi: 10.1037/a0029169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Gonzales NA, Stroh K, & Wang JJL (2006). Parent–child cultural marginalization and depressive symptoms in Asian American family members. Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 167–182. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak K (2003). Adolescents and their parents: A review of intergenerational family relations for immigrant and non-immigrant families. Human Development, 46, 115–136. doi: 10.1159/000068581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai AC, Zhang Z-X, & Wang W-Z (2000). Maternal child-rearing practices in Hong Kong and Beijing Chinese families: A comparative study. International Journal of Psychology, 35,60–66. doi: 10.1080/002075900399529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM (2003). Do ethnic identity and other-group orientation protect against discrimination for Asian Americans? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 133–141. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, & Lamb ME (2013). Fathers in Chinese culture In Shwalb DW, Shwalb BJ, & Lamb ME (Eds.), Fathers in cultural context (pp. 15–41). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Low SM, & Stocker C (2005). Family functioning and children’s adjustment: Associations among parents’ depressed mood, marital hostility, parent–child hostility, and children’s adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 394–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, & Austin JT (2000). Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 201–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Kim J-Y, Burton LM, Davis KD, Dotterer AM, & Swanson DP (2006). Mothers’ and fathers’ racial socialization in African American families: Implications for youth. Child Development, 77,1387–1402.doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil S, Harris-McKoy D, Brantley C, Fincham F, & Beach SH (2014). Middle class African American mothers’ depressive symptoms mediate perceived discrimination and reported child externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 381–388. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9788-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Benner AD, Tan CS, & Kim SY (2009). Family economic stress and academic well-being among Chinese-American youth: The influence of adolescents’ perceptions of economic strain. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 279–290. doi: 10.1037/a0015403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagne B, Kessels RC, Frigerio E, de Haan EF, & Perrett D (2005). Sex differences in the perception of affective facial expressions: Do men really lack emotional sensitivity? Cognitive Processing, 6, 136–141. doi: 10.1007/s10339-005-0050-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK,&Muthen BO.(1998–2015).Mplususer’s guide (7th ed). Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Palkovitz R, Trask BS, & Adamsons K (2014). Essential differences in the meaning and processes of mothering and fathering: Family systems, feminist and qualitative perspectives. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 6, 406–420. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette D (2004). Theorizing the father–child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Human Development, 47, 193–219. doi: 10.1159/000078723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, & Widaman KF (2004). Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American families. Child Development, 75, 1632–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K (2014). Financial stress, parent functioning and adolescent problem behavior: An actor–partner interdependence approach to family stress processes in low-, middle-, and high-income families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1752–1769. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0159-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K, Van Leeuwen K, Wouters E, & Mortelmans D (2014). A family system approach to investigate family-based pathways between financial stress and adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25, 765–780. doi: 10.1111/jora.12171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riina EM, & McHale SM (2010). Parents’ experiences of discrimination and family relationship qualities: The role of gender. Family Relations, 59, 283–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00602.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield TJ, Parke RD, Kim Y, & Coltrane S (2008). Bridging the acculturation gap: Parent–child relationship quality as a moderator in Mexican American families. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1190–1194. doi: 10.1037/a0012529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teubert D, & Pinquart M (2010). The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A metaanalysis. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10, 286–307. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2010.492040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). The Asian population: 2010. Retrieved fromhttp://www.census.gov/prod/-cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2013). Asians fastest-growing race or ethnic group in 2012, Census Bureau Reports. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2013/cb13-112.html

- Wei M, Ku T-Y, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, & Liao KY-H (2008). Moderating effects of three coping strategies and self-esteem on perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms: A minority stress model for Asian international students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 451–462. doi: 10.1037/a0012511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RB, Zeiders K, Knight G, Roosa M, & Tein J-Y (2014). Mexican origin youths’ trajectories of perceived peer discrimination from middle childhood to adolescence: Variation by neighborhood ethnic concentration. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1700–1714. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0098-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia YR, Do KA, & Xie X (2013). The adjustment of Asian American families to the US context: The ecology of strengths and stress In Peterson GW & Bush KR (Eds.), Handbook of marriage and the family (3rd ed, pp. 705–722). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Gee GC, & Takeuchi DT (2008). Racial discrimination and psychological distress: The impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States-born Asian adults. Developmental Psychology, 44, 787–800. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]