Abstract

Researchers define self-advocacy as the ability of an individual with cancer to overcome challenges in getting their preferences, needs, and values met. While imperative in all health care settings, self-advocacy is especially important in cancer care. The goal of this article is to present a conceptual framework for self-advocacy in cancer. We review foundational studies in self-advocacy, define the elements of the conceptual framework, discuss underlying assumptions of the framework, and suggest future directions in this research area. This framework provides an empirical and conceptual basis for studies designed to understand and improve self-advocacy among women with cancer.

Keywords: cancer, communication, conceptual framework, decision-making, self-advocacy, social support

THE 2013 Institute of Medicine Report, Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis, identified that person-centered care is not widely instituted within the United States despite being a central tenet of high-quality cancer care. The model presented in the report specifies 3 elements required for person-centered care: (a) health care providers who are equipped with communication skills and focused on their patients, (b) health care systems that are accessible and responsive, and (c) individuals who are informed and participate actively in their care.1 Barriers to enacting person-centered care exist at each of these levels: health care providers, systems, and individuals.2 While interconnected, these groups face unique barriers to enacting person-centered care. Research has largely focused on how health care providers and systems can support person-centered care with limited attention paid to individuals. Clarifying how individuals incorporate their priorities during care can support efforts to ensure cancer care is person-centered.

“Self-advocacy” refers to the patient behaviors to get their preferences, needs, and values met in the face of a challenge.3 Individuals who can self-advocate make proactive, personally meaningful decisions, effectively communicate with their health care providers, and gain strength through connection to others. These behaviors may improve individuals’ perceptions of person-centered care, symptom burden, quality of life, and health care utilization. Self-advocacy may even reduce the potential for cancer disparities in care and outcomes among individuals from marginalized groups.2,4,5 Although self-advocacy applies to all individuals with cancer, research has largely focused on women. Women not only experience different types of malignancies and cancer-and treatment-related symptoms,6,7 but also communicate with their providers, negotiate treatment options, and make health care decisions in distinctive ways.8,9

Over the past 8 years, research related to cancer self-advocacy has grown to the point where it is possible to present a cohesive conceptual framework that defines the components of self-advocacy and explicates the concepts and relationships within the framework. A conceptual framework creates a shared understanding and purpose among researchers and allows for the comparison and integration of results across studies, thereby more efficiently building the evidence base in this area. Researchers can apply this empirical evidence to create effective, efficient self-advocacy interventions that improve patient outcomes.

The purpose of this article is to present a conceptual framework for self-advocacy among women with cancer. This article defines our current framework of self-advocacy and discusses its underlying assumptions. Finally, it suggests priority areas for future research to test this conceptual framework.

RESEARCH LEADING TO THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The self-advocacy framework is a product of several research studies led by our research group. These studies clarified how self-advocacy is (a) defined in the literature, (b) experienced by women with cancer, (c) related to similar constructs, and (d) comprised of dimensions. The Table lists each successive study’s purpose, methodology, and pertinent results. We continuously refined our definition and self-advocacy framework with each study, resulting in the current framework.

First, we conducted a concept analysis of self-advocacy in cancer survivorship to develop a parsimonious definition and unified understanding of self-advocacy based on a synthesis of peer-reviewed and gray literature.10 This concept analysis addressed the similarities and differences in conceptualizations of self-advocacy across diverse chronic illnesses. The self-advocacy scholarship of Brashers in HIV/AIDS,14 Test in disabilities,15 Jonikas in mental health,16 and Walshe-Burke in cancer survivorship17 were pivotal in developing our initial conceptualization. McCorkle’s research on self-management in cancer was foundational in helping refine the initial definition of self-advocacy and situate it within the literature.18 Through the synthesis of these areas of scholarship, we arrived at an initial framework of self-advocacy in cancer survivorship including precursors, defining characteristics, and proximal outcomes of self-advocacy.10

Second, we complemented the concept analysis by examining the lived experience of self-advocacy. We conducted focus groups and interviews with women with ovarian cancer, asking them to broadly define how they self-advocate in the context of cancer and symptom management. Our qualitative analysis resulted in 2 major themes of self-advocacy: (a) “knowing who I am and keeping my psyche intact,” and (b) “knowing what I need and fighting for it.” Subthemes included knowing how and when to seek out information, being proactive in managing health care providers, and taking advantage of social support.11

Based on this study, we decided to focus our self-advocacy research on women with cancer. The experiences women described, compared to previous work in largely male samples, reflected gender differences in communication, negotiation, and utilization of social networks, which directly impact self-advocacy skills.19,20 While we believe that our definition likely also reflects aspects of self-advocacy among men with cancer, we are evaluating the similarities and differences in ongoing research.

Third, we integrated the results of the preceding studies to create a measure of self-advocacy in women with cancer. Because the concept analysis focused on all cancer survivors and the focus group study focused on women with ovarian cancer, we specifically worked to ensure the measure (a) retained aspects of self-advocacy particular to women and (b) remained applicable across all cancer types. We created an exhaustive list of behaviors indicative of self-advocacy in women. We made survey items reflecting these behaviors and tested their content validity and reliability to ensure that the measure would capture the depth and breadth of the concept of self-advocacy and could be consistently administered. We evaluated content validity among a group of cancer researchers and clinicians, female health psychologists, cancer advocates, and individuals with a history of cancer. We assessed reliability with a sample of women with a history of cancer (both in and out of treatment). We confirmed that the initial measure represented self-advocacy and that the item responses were internally consistent and consistent over time.12

Finally, we tested the measure’s construct validity among a large, national sample of women with cancer. This study confirmed that the measure—the Female Self-Advocacy in Cancer Survivorship Scale—is an accurate, valid assessment of women’s self-advocacy.13 We identified 3 main dimensions of behaviors indicative of self-advocacy (described later). We also established self-advocacy’s relationships with its precursors and outcomes.

By the end of the final study, we defined key self-advocacy behaviors and demonstrated how self-advocacy relates to its precursors and outcomes. These data comprise the primary evidence for the conceptual framework. We also integrated findings from other studies to ensure the framework reflects a comprehensive, robust understanding of self-advocacy.

SELF-ADVOCACY FRAMEWORK

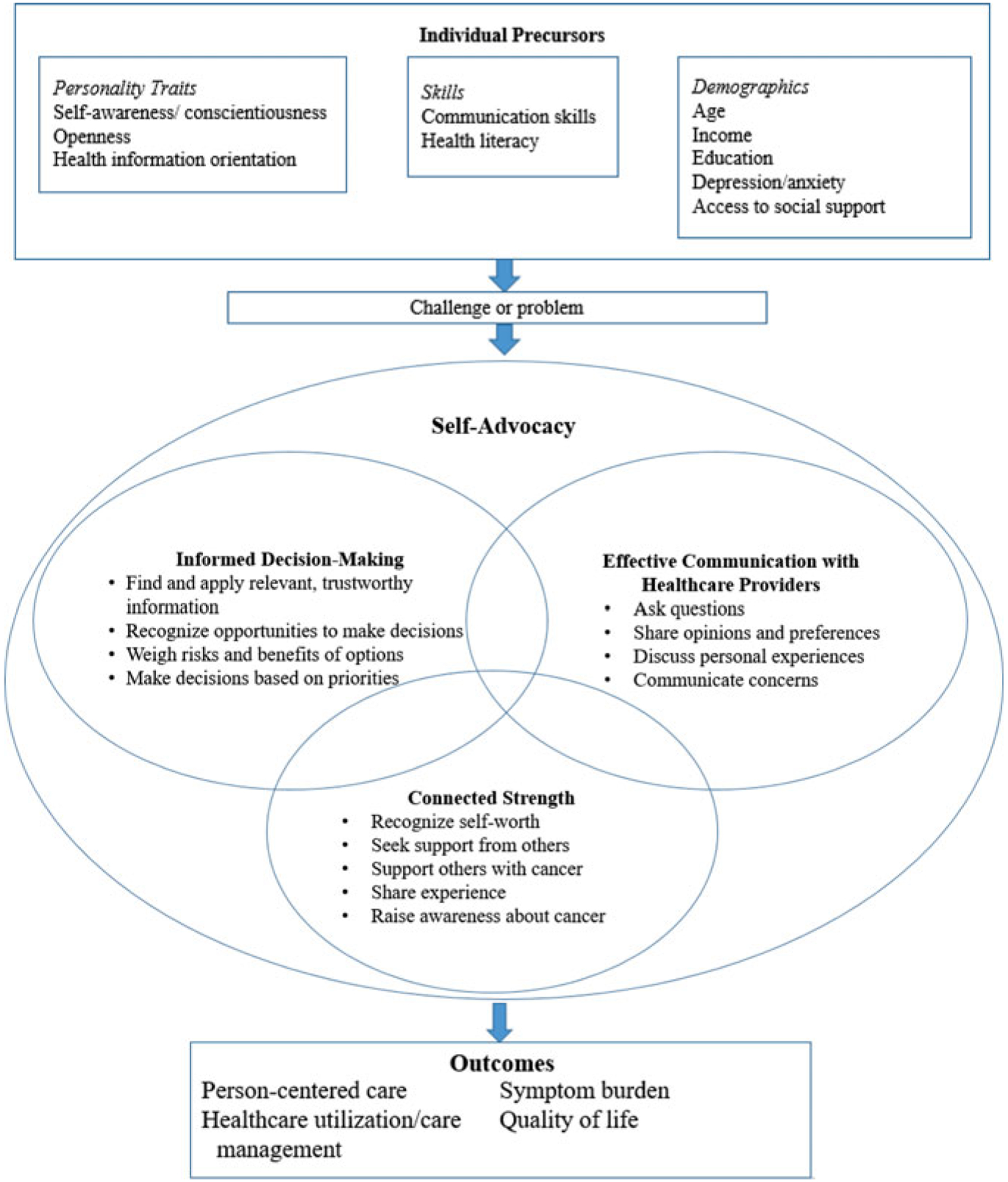

The Figure presents the self-advocacy conceptual framework. Each construct within the framework is described in-depth next.

Self-advocacy

Self-advocacy is a skillset that individuals with cancer have or learn.3,12,17 Some individuals can self-advocate based on their personality traits, skills, and demographics before being diagnosed with cancer. Others may not have these characteristics when first diagnosed and so must acquire them. Self-advocacy is comprised of behaviors necessary to overcome challenges related to their cancer. These behaviors are what allow individuals to translate their preferences, needs, and values into the care they receive from others.

Specific self-advocacy behaviors (or skills) are categorized into 3 dimensions: (a) informed decision-making, (b) effective communication with health care providers, and (c) connected strength.11,13 Examples from our previous studies provide context for each dimension.

Informed decision-making

Key informed decision-making behaviors include accessing health information, recognizing opportunities to make decisions, weighing risks and benefits of various options, and making decisions based on priorities. Finding and applying relevant, trustworthy health information to one’s unique situation is a primary step in self-advocating.3 Gaining knowledge about their cancer, treatment options, management strategies, and the health care system is an essential way in which individuals understand what they are experiencing. Equipped with this knowledge, individuals first recognize the various decision points within their care and weigh the risks and benefits of various options.21 They make decisions about their health and well-being based on their values and priorities.22,23 Individuals also use the knowledge they have collected to efficiently and purposefully navigate the health care system.24,25

Individuals in our previous studies described informed decision-making both on their own and with their health care providers. Privately, women reported performing extensive searching for trustworthy, reliable health information to understand their illness and ways to manage it. They leveraged networks of information sources (eg, the Internet, social networks, support groups, health care organizations, and advocacy groups) to find information relevant to their circumstances. To lower their burden, women asked their partners, family members, and other caregivers to gather and synthesize information on their behalf. They did this to better understand their cancer and treatment options but also to help clarify how they could strengthen their health on their own. Most individuals did this work at home without bringing information to their health care providers. When individuals did work with their health care providers to make decisions about their care, it usually focused on treatment planning after their diagnosis. Individuals requested clarification about the rationale for one treatment over others, identified the trade-offs between different options, and requested second opinions to ensure all decisions were well-informed.

Effective communication with health care providers

Collaborative, engaged communication with health care providers is a pivotal dimension of self-advocacy. Key behaviors of effective communication include asking questions, sharing opinions and preferences, discussing personal experiences, and openly communicating concerns.26–28 Individuals may struggle to communicate due to time pressures or subtle interpersonal cues from health care providers. They may experience limited opportunities to discuss topics of importance to them.29 Effective communication builds common ground between individuals with cancer and health care providers: they can address the challenges they are experiencing, concerns are mutually exchanged, and negotiations about treatment decisions are made.3,30 At times, this means individuals must explicitly request what they need or respectfully decline recommendations they do not prefer.31 This skill should not include adversarial communication, which counter-productively reduces the open exchange between individuals and their health care providers.

In our prior work, individuals described managing their cancer- and treatment-related symptoms as an important time when they needed to effectively communicate with their health care providers. For example, a woman talked about experiencing multiple treatment-related symptoms that she could not manage on her own. Despite reporting these symptoms during her clinic visits, she did not receive advice or support from her health care providers. She had to learn how to broach this subject with her providers in a way that conveyed the impact of the symptoms on her life and her need for evidence-based strategies to manage the symptoms.11

Connected strength

While the first 2 dimensions of self-advocacy focus on the individual within a health care setting, the third dimension focuses on how individuals self-advocate by gaining strength through connection to others. Key behaviors include seeking support from others, providing support to others, sharing their experience of cancer with others, and raising awareness about cancer. These behaviors occur in intra- and interpersonal spaces. Intrapersonally, individuals reevaluate their self-perceptions, establish their self-worth and value as someone with cancer, and gain strength through connection to self.32 Interpersonally, individuals’ roles as partner, parent, child, friend, and coworker shift to accommodate their cancer illness, and they gain strength by seeking and providing support to these people.33

In our prior work, individuals frequently described self-advocating by openly talking with their social networks about their need for support and requesting specific types of help. They built their inner strength by allowing themselves to step back from previous responsibilities and receive care from others. By finding a balance between giving and receiving support, they were able to care for their family and friends while still tending to their health and well-being. At times, individuals needed to fully rely on others for support (eg, when their health declined or they felt exhausted). One participant likened this to ordering an Uber: “you are in charge of where you are going, but you don’t always have to drive.”34

Individuals self-advocate by supporting others with cancer, often reinterpreting their illness as an opportunity to connect with others and raise awareness about cancer.35,36 This reciprocity serves to reassure individuals of their strength and utility in the face of their illness. As Mok and Martinson37 described, “Patients with cancer can draw strength from each other when they realize that they share a common bond. In the process of sharing their feelings and experiences of having the illness, [patients] rethink their illness and suffering.” While engaging in such peer support may not always improve individuals’ outcomes and sometimes even cause distress,38,39 women in our studies frequently endorsed benefiting from reaching out to others with cancer in small- and large-scale ways, although sometimes they needed to temper their involvement to not overextend themselves.

The 3 dimensions of self-advocacy are intended to describe distinct, additive ways of overcoming challenges. An individual may have strengths within 1 or 2 dimensions, but lack skills in another. Yet the 3 dimensions are interrelated. For example, individuals who are adept at finding and applying health information to their cancer experience are also likely to discuss that knowledge with their health care providers in a collaborative manner. Individuals therefore have an opportunity to capitalize on their existing strengths to build additional self-advocacy skills.

Individual precursors

Individuals’ propensity to self-advocate depends on their preexisting personality traits, skills, and demographics. These precursors encompass both stable and unstable characteristics that may change during an individual’s cancer experience. Individuals who have a keen sense of self-awareness/conscientiousness and openness are more likely to self-advocate because they are highly attuned to their priorities and values after a cancer diagnosis.10 Likewise, individuals who have a positive orientation toward health information are more likely to independently access and integrate the information they learn about their illness into their decision-making and communication.10

Individuals may possess communication and health literacy skills that prepare them to self-advocate. Communication skills, if developed before their cancer diagnosis, can assist individuals in learning how to effectively communicate with their health care providers.10,13 The more advanced an individual’s health literacy skills, the more they will be able to translate those skills into improved outcomes.40,41

Demographic characteristics of age, income, education, mood, and access to social support influence self-advocacy. Our work has shown that age relates to self-advocacy. Compared to younger individuals, older individuals report higher levels of engagement in decision-making and effective communication, perhaps due to having more experiences with the health care system in general.13 Individuals who report higher annual household income and education report higher levels of engagement in decision-making and effective communication.13 Depression and anxiety may limit individuals’ abilities to advocate for their needs.42 Regarding the connected strength dimension of self-advocacy, individuals who have access to supportive social networks, support groups, and advocacy organizations can readily engage in these groups and gain strength both from giving to and receiving from them.10

Challenges and problems

Unaddressed challenges or problems related to their cancer and its treatment prompt individuals to self-advocate. The framework does not specify explicit challenges for which individuals need to self-advocate. Rather, individuals recognize problems that they want to overcome, and this problem drives their self-advocacy. These challenges could involve their health and well-being, working with their health care providers, navigating the health care system, or managing their social networks.

Outcomes

After individuals engage in informed decision-making, effective communication, and/or connected strength skills, they can realize the positive outcomes of self-advocacy. While this framework presents a current set of self-advocacy outcomes, other outcomes likely exist. Where applicable, references to self-advocacy research support each outcome. When evidence is not available, conceptually similar research assists in describing probable outcomes of self-advocacy.

Self-advocacy may lead to improved person-centered care. As individuals improve their ability to make decisions and communicate with their health care providers, they become prepared to engage in person-centered care and report feeling their care reflects their preferences, needs, and values. They feel like their health care providers understand them, care for them as individuals, and are willing to collaborate with them.11 Improved person-centered care may further support more downstream outcomes that depend on the individual interacting with health care providers and health care systems. Additionally, researchers hypothesize that the quality of care will improve, as individuals navigate the health care system and become more satisfied with the care they receive.43 Women in our previous studies discussed how communicating with their health care providers about bothersome concerns allowed them to manage these concerns before they became urgent problems. By learning to be an informed decision-maker, they knew where to find information to help them manage problems on their own.11

Self-advocacy may also lead to improved symptom burden. Our descriptive studies of self-advocacy demonstrated that managing cancer- and treatment-related symptoms is a major challenge that prompts individuals to self-advocate. Symptoms like fatigue, constipation, sleep disturbance, and pain are frequently overwhelming to manage and require ongoing care. To address challenging symptoms, individuals self-advocate by communicating their symptoms with their health care providers, requesting symptom management strategies, independently seeking information about treating these symptoms, and connecting with other individuals with cancer who have experience in managing similar symptoms.44 Symptom burden (defined as symptom severity and symptom interference with life) is negatively associated with effective communication.45 As individuals effectively communicate their symptoms with their providers, they are more likely to request and receive information and support necessary to manage their symptoms.

Self-advocacy likely leads to better quality of life. Individuals who can advocate for their priorities are likely to actively seek out solutions to the problems that are negatively impacting their quality of life.46 This may lead to improvements in their overall sense of well-being as well as their physical, functional, social, emotional, and spiritual quality of life.

Finally, self-advocacy may lead to lower use of preventable health care utilization. When individuals make informed decisions about their care and effectively communicate with their health care team, individuals may address health problems as they arise rather than delaying care until the problem becomes more urgent. Moreover, by engaging in connected strength (eg, asking for and receiving support from social networks), individuals may receive the care and support to help manage problems at home. Self-advocacy may also increase phone, outpatient, and other forms of contact between individuals and their health care providers when needed to address their priorities. By engaging in such up-front contact, individuals may ultimately use fewer preventable (and more costly) services like hospitalizations and emergency department visits.47

ASSUMPTIONS UNDERLYING THE SELF-ADVOCACY FRAMEWORK

Several assumptions underlie this self-advocacy framework. First, as a skillset comprised of behaviors, the self-advocacy scale measures behaviors, allowing for empirical assessment of change, recognizing that less observable shifts in attitude may also be important. Individuals may not be ready to self-advocate because they are uncertain about how to mobilize their preexisting skills to address a particular challenge. Conversely, even if they are ready to self-advocate, individuals may need to crystalize or adjust their priorities relative to a specific challenge. Some women in our studies referred to this as a “turning point” wherein they identified what was most important to them and realized that to achieve those priorities they needed to take a more active, engaged role in their care. While not an explicit aspect of our framework, these internal processes may explain delays or barriers to self-advocacy.

In addition, while self-advocacy’s primary aim is to help ensure individuals receive care attuned to their priorities, it indirectly seeks to equip individuals to address inequities they may experience. Since person-centered care is thought to play a role in reducing disparities,48,49 concrete skills may counter the often implicit behaviors, processes, and structures within health care systems that lead to inequities. Similar to individual-level interventions to address cancer disparities, self-advocacy focuses on individuals accessing health information to make informed decisions consistent with their priorities.50 For example, an individual struggling with cancer-related pain may not be able to use self-advocacy skills to address her health care systems’ lack of palliative care services for patients experiencing cancer- or treatment-related pain. However, she could use her self-advocacy skills to access information about pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches to pain management and work closely with her health care providers to find effective approaches to reduce her pain.

FUTURE RESEARCH

This framework provides researchers with intervention targets to develop and test. Interventions should aim to improve the ability of individuals to become informed decision-makers, effective communicators with their health care providers, and strong through connection to others. Since individuals may vary in their baseline levels of each dimension, researchers could design interventions in which these targets are either integrated or complementary to each other. Interventions could augment their strengths and address areas for improvement in an engaging, motivational format. Researchers can assess the impact of these interventions by measuring self-advocacy over time using the Female Self-Advocacy in Cancer Survivorship Scale.

Future research priorities include conduct longitudinal assessments of self-advocacy and testing causal pathways between variables in the framework. Key research steps are to identify (a) the most efficacious and person-centered intervention modalities and designs and (b) ideal points within the cancer trajectory for intervention delivery. As this work matures, researchers should focus on developing evidence-based self-advocacy interventions, testing the efficacy of those interventions, and identifying the mediators and moderators of intervention efficacy. For example, some of the individual precursors, when operationalized within a self-advocacy intervention study, may affect the degree to which the intervention impacts patient outcomes and so be included as intervention moderators. Researchers should also aim to define subgroups of individuals most likely to report low self-advocacy so that interventions can target those at-risk groups. Data derived from future studies will allow researchers to adjust the current conceptual framework.

Researchers can also extend the current framework to clarify how providers and sys either support or hinder individuals in self-advocating. For example, individuals may struggle to self-advocate when providers lack training in caring for diverse patient cultures and beliefs; organizational cultures limit input from individuals; or providers and systems are not supported in collaborating with individuals regarding their cancer care.29,51 Expanding the framework to address such health care provider and system barriers provides additional pathways to improve self-advocacy and person-centered care.

DISCUSSION

This article presents a conceptual framework of self-advocacy in women with cancer. This framework emphasizes the skills necessary to ensure women’s preferences, needs, and values are incorporated to address the myriad challenges they face. These self-advocacy skills include engaging in personally meaningful decision-making, effectively communicating with health care providers, and building strength through connection to others. The framework ties these self-advocacy behaviors to precursors and outcomes, creating pathways by which self-advocacy can improve patient outcomes.

Self-advocacy purposefully focuses on the role of individuals in achieving person-centered care among other positive outcomes. However, this framework does not intend to place the burden of creating person-centered care onto individuals. Individuals function within a larger context of cancer care. Research addressing how health care providers and systems impact an individual’s ability to self-advocate will complement the existing research. An exploratory study demonstrated conflicting views of self-advocacy between women with cancer and their health care providers.29 Additional research should seek to understand how individuals and health care providers can work together to support patients’ ability to get their needs met. Undoubtedly, health care providers and systems that do not practice person-centered care are likely to miss opportunities to support individuals’ self-advocacy efforts.

CONCLUSION

The self-advocacy framework provides an empirical and conceptual basis to define the mechanisms through which individuals work to have their priorities recognized within their cancer care. The key behaviors of self-advocacy can inform the design of interventions and care intended to help individuals overcome challenges related to their cancer care. As researchers expand and adjust the empirical evidence validating this framework, they can further elucidate how self-advocacy impacts patient outcomes.

Figure.

Conceptual framework of female self-advocacy in cancer.

Table.

Progression of Studies Leading to the Self-advocacy Conceptual Framework

| Order of Studies | Study Methodology and Citation | Study Purpose (as Stated in Each Article) | Main Results Related to Conceptual Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Concept analysis of self-advocacy in cancer survivorship10 | “To report an analysis of the concept of self-advocacy among individuals with cancer to clarify its meaning, to differentiate this meaning with related concepts, and to unify understanding of the concept in cancer research and practice.” |

|

| 2. | Focus groups of self-advocacy in women with ovarian cancer11 | “To explore ovarian cancer survivors’ experiences of self-advocacy in symptom management.” |

|

| 3. | Creation of a self-advocacy scale for women with a history of cancer12 | To report “the development of the Female Self-Advocacy in Cancer Survivorship Scale’s conceptual underpinnings and item development” including “evaluations of the measure’s content validity and reliability. ” |

|

| 4. | Validation of the Female Self-Advocacy in Cancer Survivorship Scale13 | “To develop and psychometrically test the validity of the Female Self-Advocacy in Cancer Survivorship Scale.” |

|

Statement of Significance.

What is known or assumed to be true about this topic:

Self-advocacy (defined as an individual’s ability to get her preferences, needs, and values met in the face of a challenge) is a critical skill for individuals with cancer because it is associated with improved patient-reported outcomes. Currently, there is no framework guiding self-advocacy research.

What this article adds:

This article presents a conceptual framework for self-advocacy among women with cancer. The authors summarize previous research on which this framework is based and list priorities for future research. The conceptual framework can guide researchers in designing and implementing studies to improve individuals’ self-advocacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to dedicate this article to the late Susan M. Cohen, PhD, APRN, FAAN. She was a dedicated member of our research team and brought clarity of thought, enthusiasm, and reassurance to each of our studies described in this article. As a mentor, she endlessly supported this work and the development of all of her mentees. Without her guidance, along with that of our entire team of mentors and collaborators, this work would never have reached fruition.

The following funding supported this article: American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant MSRG-18-051-51 (Thomas), National Palliative Care Research Center Career Development Award (Thomas), American Cancer Society, Doctoral Degree Scholarship in Cancer Nursing DSCN-14-077-01-SCN (Thomas), National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institute of Health F31NR014066 (Thomas), National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institute of Health T32NR0111972 (Bender), National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institute of Health R01NR010735 (Donovan), Judith A. Erlen Nursing PhD Student Research Award (Thomas), Nightingale Awards of Pennsylvania, Doctoral Student Research Award (Thomas), Oncology Nursing Foundation, Doctoral Student Award (Thomas), Sigma Theta Tau International, Rosemary Berkel Crisp Research Award (Thomas), The Rockefeller University’s Heilbrunn Family Center for Research Nursing, Heilbrunn Nurse Scholar (Thomas) Award, and Palliative Research Center (PaRC) at the University of Pittsburgh (Schenker).

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levit LA, Balogh EP, Nass SJ, Ganz PA. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff. 2010;29(8):1489–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark EJ, Stovall EL. Advocacy: the cornerstone of cancer survivorship. Cancer Pract. 1996;4(5):239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart Moira, Judith Belle Brown Allan Donner, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miaskowski C Gender differences in pain, fatigue, and depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;0610(32):139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keogh E Gender differences in the nonverbal communication of pain: a new direction for sex, gender, and pain research? Pain. 2014;155(10):1927–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertakis KD, Franks P, Epstein RM. Patient-centered communication in primary care: physician and patient gender and gender concordance. J Womens Heal. 2009;18(4):539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall JA, Roter DL. Patient gender and communication with physicians: results of a community-based study. Womens Health. 1995;1(1):77–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagan TL, Donovan HS. Self-advocacy and cancer: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(10):2348–2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagan TL, Donovan HS. Ovarian cancer survivors’ experiences of self-advocacy: a focus group study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(2):140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagan TL, Cohen S, Stone C, Donovan H. Theoretical to tangible: creating a measure of self-advocacy for female cancer survivors. J Nurs Meas. 2016;24(3): 428–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagan TL, Cohen SM, Rosenzweig MQ, Zorn K, Stone CA, Donovan HS. The Female Self-Advocacy in Cancer Survivorship Scale: a validation study. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(4):976–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brashers DE, Haas SM, Neidig JL. Patient self-advocacy scale: measuring patient involvement in health care decision-making interactions. Health Commun. 1999;11(2):97–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Test DW, Fowler CH, Wood WM, Brewer DM, EddyS. A conceptual framework of self-advocacy for students with disabilities. Remedial Spec Educ. 2005; 26(1):43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonikas JA, Grey DD, Copeland ME, et al. Improving propensity for patient self-advocacy through wellness recovery action planning: results of a randomized controlled trial. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(3):260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh-Burke K, Marcusen C. Self-advocacy training for cancer survivors: the cancer survival toolbox. Cancer Pract. 1999;7(6):297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(1):50–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Street RL. Gender differences in health care provider-patient communication: are they due to style, stereotypes, or accommodation? Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(3):201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arden-Close E, Absolom K, Greenfield DM, Hancock BW, Coleman RE, Eiser C. Gender differences in self-reported late effects, quality of life and satisfaction with clinic in survivors of lymphoma. Psychooncology. 2011;20(11):1202–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong ST, Butow PN, Tong A, et al. Patients’ experiences and perspectives of multiple concurrent symptoms in advanced cancer: a semi-structured interview study. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(3): 1373–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borgmann-Staudt A, Kunstreich M, Schilling R, et al. Fertility knowledge and associated empowerment following an educational intervention for adolescent cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2019;28(11):2218–2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharf BF. Communicating breast cancer on-line: support and empowerment on the Internet. Women Health. 1997;26(1):65–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowan RA, Shuk E, Byrne M, et al. Factors associated with use of a high-volume cancer center by Black women with ovarian cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2019; 15(9):e769–e776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purtzer MA, Hermansen-Kobulnicky CJ. “Being a part of treatment”: the meaning of self-monitoring for rural cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(2):93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alpert JM, Morris BB, Thomson MD, Matin K, Brown RF. Identifying how patient portals impact communication in oncology. Health Commun. 2019; 34(12):1395–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shay LA, Lafata JE. Understanding patient perceptions of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volker DL, Becker H, Kang SJ, Kullberg V. A double whammy: health promotion among cancer survivors with preexisting functional limitations. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(1):64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagan T, Rosenzweig M, Zorn K, van Londen J, Donovan H. Perspectives on self-advocacy: comparing perceived uses, benefits, and drawbacks among survivors and providers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017; 44(1):52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eid M, Nahon-Serfaty I. Risk, activism, and empowerment. Int J Civ Engagem Soc Chang. 2015;2(1):43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peitzmeier SM, Bernstein IM, McDowell MJ, et al. Enacting power and constructing gender in cervical cancer screening encounters between transmasculine patients and health care providers [published online ahead of print October 29, 2019]. Cult Health Sex. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2019.1677942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wittal DM. Bridging the gap from the oncology setting to community care through a cross-Canada environmental scan. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2018;28(1): 38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulsara C, Ward A, Joske D. Haematological cancer patients: achieving a sense of empowerment by use of strategies to control illness. J Clin Nurs. 2004; 13(2):251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hagan TL, Schmidt K, Ackison GR, Murphy M, Jones JR. Not the last word: dissemination strategies for patient-centered research in nursing. J Res Nurs. 2017;22(5):388–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molina Y, Scherman A, Constant TH, et al. Medical advocacy among African-American women diagnosed with breast cancer: from recipient to resource. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(7):3077–3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mok E, Martinson I, Wong TKS. Individual empowerment among Chinese cancer patients in Hong Kong. West J Nurs Res. 2004;26(1):59–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mok E, Martinson I. Empowerment of Chinese patients with cancer through self-help groups in Hong Kong. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23(3):206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helgeson VS, Cohen S, Schulz R, Yasko J. Long-term effects of educational and peer discussion group interventions on adjustment to breast cancer. Heal Psychol. 2001;20(5):387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kowitt SD, Ellis KR, Carlisle V, et al. Peer support opportunities across the cancer care continuum: a systematic scoping review of recent peer-reviewed literature. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(1):97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(suppl 1):S19–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balogh EP, Ganz PA, Murphy SB, Nass SJ, Ferrell BR, Stovall E. Patient-centered cancer treatment planning: improving the quality of oncology care. Summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. Oncologist. 2011;16(12):1800–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. Br Med J. 2001;323(7318):908–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Te Boveldt N, Vernooij-Dassen M, Leppink I, Samwel H, Vissers K, Engels Y. Patient empowerment in cancer pain management: an integrative literature review. Psychooncology. 2014;23(11):1203–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hagan TL, Gilbertson-White S, Cohen SM, Temel JS, Greer JA, Donovan HS. Symptom burden and self-advocacy: exploring the relationship among female cancer survivors. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(1):E23–E30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim NLY, Shorey S. Effectiveness of technology-based educational interventions on the empowerment related outcomes of children and young adults with cancer: a quantitative systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(10):2072–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuijpers W, Groen WG, Aaronson NK, Van Harten WH. A systematic review of web-based interventions for patient empowerment and physical activity in chronic diseases: relevance for cancer survivors. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beach MC, Rosner M, Cooper LA, Duggan PS, Shatzer J. Can patient-centered attitudes reduce racial and ethnic disparities in care? Acad Med. 2007;82(2): 193–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilkerson LA, Fung CC, May W, Elliott D. Assessing patient-centered care: one approach to health disparities education. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 2): S86–S90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Quality Forum. Effective Interventions in Reducing Disparities in Healthcare and Health Outcomes in Selected Conditions. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiltshire J, Cronin K, Sarto GE, Brown R. Self-advocacy during the medical encounter: use of health information and racial/ethnic differences. Med Care. 2006;44(2):100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]