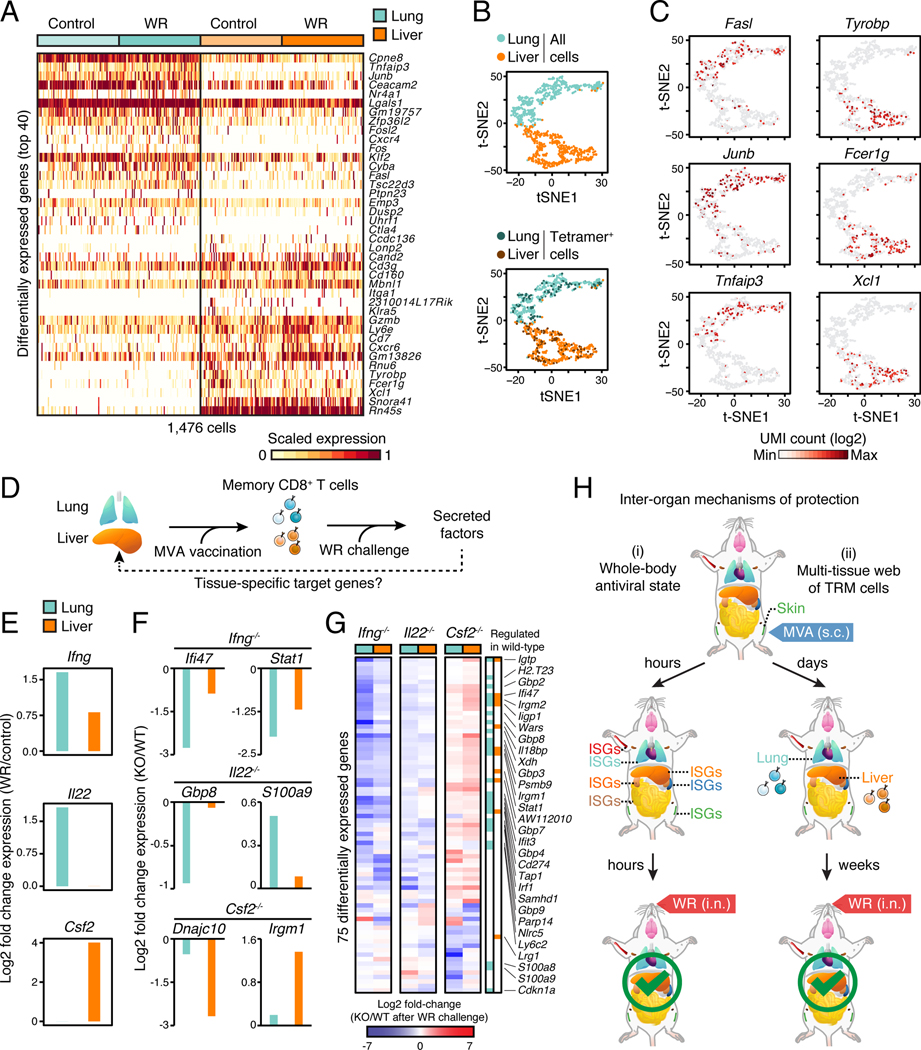

Figure 7. Local tissue environments shape the functional abilities of memory CD8+ T cells to bolster organ-specific responses.

(A) Heatmap of 1,476 single memory CD8+ T cells (columns) showing the top 40 differentially expressed genes (rows) between lung and liver of control (MVA vaccination only) and WR-challenged mice (FDR < 0.01, expression fold change > 3).

(B) Visualization of single cells from lung and liver in MVA-vaccinated mice (Control) using t-SNE. Vaccinia virus peptide B8R-specific (H2-Kb B8R20–27) CD8+ T cells (Tetramer+) are labeled in the bottom plot for lung (25.4%, 94/370 cells) and liver (25.3%, 93/368 cells).

(C) Expression levels of tissue-specific genes in single cells. t-SNE plot from B colored based on expression levels (UMI, unique molecular identifiers) of indicated genes.

(D) Illustration of the impact of tissue-adapted memory CD8+ T cells on their respective tissue of residence. From left to right, vaccination at skin seeds memory CD8+ T cells in lung and liver, which secrete factors controlling tissue responses upon WR challenge.

(E) Secreted factor induction in lung and liver at day 0.5 after WR challenge of MVA-vaccinated mice. Fold change values were calculated using single-cell RNA-seq profiles from WR-challenged versus vaccinated only mice as control.

(F-G) Tissue-level expression changes for target genes of secreted factors produced in memory CD8+ T cells. Mice were immunized at skin with MVA and challenged 3 weeks later with WR intranasally for 1.5 days. Shown are log2 fold-change values of knockout (KO) relative to wild-type (WT) mice for selected (F) and all differentially expressed genes (G) (FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.05, absolute fold change > 2, n = 4).

(H) Schematic depicting the inter-organ mechanisms of protection reported in this study. Upon skin MVA vaccination, type I IFNs produced locally trigger a whole-body antiviral state within hours (i; left), and tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells (TRM) seeded in distant tissues help block viral spread (ii; right).