Abstract

Objective

Adolescents with cystic fibrosis (CF) often face a unique set of difficulties and challenges as they transition to adulthood and autonomy while also managing a progressive illness with a heavy treatment burden. Coping styles have been related to changes in physical health among youth with chronic illness more generally, but the directionality of these links has not been fully elucidated. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate bidirectional links between coping styles and physical health indicators among adolescents with CF over time.

Methods

Adolescents (N = 79, 54% female) recruited from inpatient and outpatient CF clinics at two sites completed questionnaires assessing secular and religious/spiritual coping styles at two time points (18 months apart, on average). Health indicators including pulmonary functioning, nutritional status, and days hospitalized were obtained from medical records.

Results

More frequent hospitalizations predicted lower levels of adaptive secular coping over time. However, poorer pulmonary functioning predicted higher levels of positive religious/spiritual coping. The number of days hospitalized was related to adaptive secular coping and negative religious/spiritual coping.

Conclusions

Among youth with CF, physical health functioning is more consistent in predicting coping strategies than the reverse. Poorer pulmonary functioning appears to enhance adaptive coping over time, suggesting resilience of adolescents with CF, while more frequent hospitalizations may inhibit the use of adaptive coping strategies. Findings support the use of interventions aimed at promoting healthy coping among hospitalized adolescents with CF.

Keywords: adolescents, coping skills and adjustment, cystic fibrosis, longitudinal research

Introduction

Approximately 30,000 individuals in the United States currently live with cystic fibrosis (CF), a chronic and progressive disease predominantly affecting individuals of European descent (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2017). CF is specifically characterized by the buildup of thick, sticky mucus in the lungs, pancreas, and other organs, which has cascading health effects typically resulting in pulmonary and gastrointestinal difficulties (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2017). Markers of physical health in patients with CF typically include: (a) pulmonary functioning via the percentage of forced expiratory volume per second (FEV1; ≥70% = normal/mildly impaired, 40–60% = moderately impaired, ≤40 = severely impaired; mean FEV1% among individuals with CF in 2016 was 93.2 for individuals ages 6–17; this number decreases to 68.4 for individuals 18 and older; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2017); (b) body mass index and body mass index percentile (BMI/BMI percentile; goal for children and adolescents with CF is a BMI percentile at or above 50; median BMI percentile of 55.2 in children and adolescents; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2017); and (c) hospitalizations (4.4 mean outpatient visits per year, 20.1 mean days hospitalized per year for pulmonary exacerbations; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2017).

Physical functioning has been linked to psychosocial functioning among individuals with CF, acting as a strong predictor of quality of life and psychosocial functioning (Anderson et al., 2001; Mitmansgruber et al., 2016; Sawicki et al., 2011; Wahl et al., 2005a). Adolescents and adults with more severe disease progression consistently reported poorer physical, social, and emotional functioning, and higher levels of treatment burden and non-adherence, lower body image, and difficulty functioning in a job or in college courses (Gee et al., 2003). Perceived illness severity was also linked with poorer social adjustment among adults with CF (Dill et al., 2013; Findler et al., 2014). While disease severity and treatment burden are implicated in the quality of life and adjustment of individuals with CF, certain coping styles and strategies can offset many of the detrimental effects of CF-related stress (Staab et al., 1998).

To manage perceived levels of stress, many individuals turn to either secular (i.e., non-religious/spiritual) and/or religious/spiritual types of coping. Secular coping among individuals with chronic health conditions is considered multidimensional, consisting of two types of strategies: (a) control coping; and (b) disengagement coping. First, control coping involves directly managing the stress with applied behavioral strategies aimed at improving objective events or conditions (primary control coping such as problem solving) and cognitive strategies aimed at changing one’s internal state to better handle or manage stress (secondary control coping such as acceptance or positive thinking; Compas et al., 2001, 2012; Connor-Smith et al., 2000; Rudolph et al., 1995). No type of coping is universally considered to be adaptive or maladaptive; however, control coping strategies are generally considered to be more helpful, as they are frequently linked with positive outcomes and better adjustment (Compas et al., 2012). By contrast, disengagement coping, which involves detachment strategies such as denial or avoidance to disengage from or relinquish the stress, is generally considered unhelpful as it is associated with poorer outcomes (Compas et al., 2001, 2012; Connor-Smith et al., 2000).

Religious/spiritual coping is another coping style that also utilizes cognitive and behavioral practices to manage stress but with religious/spiritual components (Pargament et al., 2000). Similar to secular coping, religious/spiritual coping also has subtypes generally considered to be either adaptive or maladaptive. The adaptive form, positive religious/spiritual coping, consists of benevolent religious reappraisal and religious forgiveness (e.g., using religion to accept circumstances and let go of anger), whereas the maladaptive form, negative religious/spiritual coping, includes spiritual discontent and demonic reappraisal (e.g., believing a negative situation is a punishment from God; Pargament et al., 2000). Religious/spiritual coping has been identified as a unique and important coping strategy that helps individuals understand and cope with difficult life stressors, including chronic illnesses like CF. In fact, religious/spiritual coping has effects that may surpass those of secular coping (Hymovich & Baker, 1985; Pargament, 2002; Pendleton et al., 2002).

Theories of coping posit that, when facing an uncontrollable stressor such as a chronic illness, coping strategies are most effective when they attempt to bolster one’s own abilities to handle the stress rather than working to directly affect or change the stressor (Rudolph et al., 1995). It follows that secondary control coping strategies and positive religious spiritual coping—both of which act to strengthen one’s own mental state/self-efficacy or increase perceived support and positive thinking—would be linked with improved outcomes among individuals with CF (Rudolph et al., 1995). Indeed, among young adults with CF, optimistic acceptance and hopefulness were linked with better adherence to treatment (Abbott et al., 2001). Further, higher use of positive religious/spiritual coping in adolescents with CF predicted a slower decline in pulmonary function, more stable nutritional status, and fewer hospitalizations over a 5-year period (Reynolds et al., 2014). A decline in pulmonary functioning was also associated, however, with higher odds of using negative religious/spiritual coping strategies in youth with CF (Grossoehme et al., 2013). Similarly, poorer health trajectories were found to precede, but not follow, more negative religious/spiritual coping over time (Grossoehme et al., 2013; Reynolds et al., 2014). These studies identify important links between both secular and religious/spiritual coping and health outcomes in youth with CF, though the direction of these relations is not clear.

Indeed, few studies have investigated these links over time and no studies to our knowledge have evaluated the bidirectional nature of these relations among CF populations. Findings regarding the directionality of these relations over time (i.e., does coping predict health indicators or vice versa) have important clinical implications, not only to inform targets for clinical interventions (e.g., to promote certain aspects of coping that may be associated with improved physical functioning or to provide intervention to specific individuals with a particular physical health marker that may be associated with poorer coping) but also to guide clinical care (e.g., by informing when clinical interventions may be most salient and for whom). Similarly, concurrent associations yield important information about the correlations between factors at the same point in time while also allowing for comparison with other cross-sectional studies. Given the shifts in development and coping that occur during early adolescence (e.g., ages 12–16), understanding coping during this period specifically is essential (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2006). Adolescents with CF specifically appear to experience unique challenges and difficulties as they begin to transition to autonomy and adulthood including unique lifestyle restriction factors (falling behind and being out of the loop socially, limited independence and loss of freedom, physical incapacities, and social isolation), resentment of their chronic treatments (cannot escape the illness, disempowered in their own health management, and treatment fatigue in the face of unrelenting and exhausting therapies), and emotional vulnerability (feeling as though they are a burden on their families, anxious about the financial burden of their disease, heightened self-consciousness and embarrassment about physical symptoms and limitations, feeling helpless and powerless, and feeling overwhelmed about transitioning to adult care; Jamieson et al., 2014).

Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify the reciprocal links between health indicators (FEV1%, BMI percentile, number of days hospitalized) and coping styles (secular and religious/spiritual) among adolescents with CF both concurrently and over time. We hypothesized that (a) higher levels of adaptive secular (which includes both primary and secondary control coping strategies) and positive religious/spiritual coping would be related to better physical functioning (e.g., higher levels of FEV1%/BMI and lower number of days hospitalized) concurrently and also predict better physical functioning over time; (b) higher levels of maladaptive secular and negative religious/spiritual coping would be related to poorer physical functioning concurrently and also predict poorer physical functioning over time; and (c) better physical functioning would be related to higher use of adaptive/positive coping strategies and lower use of maladaptive/negative coping strategies both concurrently and over time.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedures

Seventy-nine adolescents with CF (46.8% male) between the ages of 12 and 18 (Mage = 14.7, SD = 1.8) were recruited from 2015 to 2017 from CF outpatient and inpatient settings at two children’s hospitals in the Southeast (n = 47) and Midwest (n = 32) U.S. (77% participation rate) as part of a larger online intervention study; intervention status was carefully considered in the current study and specifically considered as a covariate in analyses (see Preliminary Analyses section). Sample descriptives are presented in Tables I and II. Inclusion criteria included fluency in English and no known diagnosis of a developmental disability, intellectual disability, or psychosis; exclusion criteria included the presence of one of these aforementioned diagnoses, individuals outside of the designated age range at the time of enrollment, and youth without a parent/caregiver willing and able to participate. After providing written informed consent/assent, participants completed online or paper questionnaires during their visit or at home after their visit (baseline). On average, 18 months later, 56 adolescents (71% retention rate) completed an identical online or paper questionnaire (follow-up). No differences were identified between adolescents retained and not on any demographic or baseline coping variable. Similarly, no differences were identified between adolescents recruited from inpatient versus outpatient clinic settings on any demographic or baseline coping variable. Written and verbal instructions for questionnaire completion were provided during the recruitment and at the follow-up. Each participant was compensated for their time with Visa gift cards. Health indicators were collected from the CF Foundation registry. University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Table I.

Descriptive Statistics of Demographics for Adolescents.

| Variable | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (baseline) | 14.75 (1.79) |

| Time between baseline and follow-up (years) | 1.53 (0.79) |

| Time since diagnosis (years from baseline) | 12.43 (3.93) |

| Variables | % (n) |

| Gender (% female) | 54 (43) |

| Race | |

| White | 96 (75) |

| Black | 3 (2) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Disease modifying medication (% yes) | 34 (27) |

| Enrollment site (% Southeast U.S.) | 60 (47) |

| Religious affiliation | |

| Christian | 85 (67) |

| Other | 5 (4) |

| No affiliation | 10 (8) |

| Household annual income | |

| Less than $15,0000 | 9 (7) |

| $15,001–$35,000 | 21 (16) |

| $35,001–$50,000 | 10 (8) |

| $50,001–$80,000 | 21 (16) |

| Greater than $80,001 | 39 (31) |

Measures

Secular Coping

To assess secular coping styles, adolescents completed the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997) at baseline and follow-up. The Brief COPE (Carver, 1997) is a 28-item measure yielding 14 coping strategies: 8 considered adaptive (active coping, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance, and religion) and 6 maladaptive (self-distraction, denial, substance use, behavioral disengagement, venting, and self-blame). The measure asks participants to rate the frequency of various coping strategies on a 4-point scale (“I haven’t been doing this at all” [0] to “I’ve been doing this a lot” [3]). The items on each scale were averaged to create adaptive and maladaptive coping scales. Higher scores indicated higher levels of adaptive and maladaptive secular coping. Reliability statistics was mostly acceptable for adaptive and maladaptive secular coping at baseline (α = .85 and .74) and follow-up (α = .87 and .62). Of note, removing items did not substantially improve the reliability of the maladaptive coping subscale; given that the Crohnbach’s alpha was within acceptable range at baseline (α = .74), all items were retained for each subscale.

Religious/Spiritual Coping

Adolescents also completed the Brief RCOPE (Pargament et al., 2000) at baseline and follow-up. The Brief RCOPE is a self-report measure of positive and negative religious/spiritual coping that has been validated in both pediatric and adult samples (Cotton et al., 2012; Pargament et al., 2000). It consists of 14 items that yield two 7-item subscales of positive and negative religious/spiritual coping. The measure asks participants to rate the frequency of various spiritual and religious coping strategies on a four-point scale (“not at all” [0] to “a great deal” [3]). Positive religious/spiritual coping includes seeking spiritual support or collaboration from God, as well as benevolent religious reappraisals (e.g., “I seek God’s love and care”). Negative religious/spiritual coping includes spiritual discontentment, negative reappraisals of God’s powers, or demonic reappraisals (e.g., “I wonder whether my church had abandoned me”). The items on each scale were averaged to create the scales. Higher scores indicated higher levels of positive and negative religious/spiritual coping. Reliability statistics was acceptable for positive and negative religious/spiritual coping at baseline (α = .93 and .83) and follow-up (α = .96 and .79).

Pulmonary Functioning

Percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1%) was gathered from all available outpatient clinic visits during a baseline (6 months prior to completion of the baseline survey) and follow-up period (6 months prior to completion of the follow-up survey). All available FEV1% values were averaged for each participant for the baseline and follow-up periods. Higher FEV1% scores represent better pulmonary functioning.

Nutritional Status

Similar to FEV1%, BMI percentile data were gathered from all available outpatient clinic visits during the 6-month baseline and follow-up period. All available BMI percentiles were averaged for each participant during each period. As with FEV1%, higher BMI percentiles indicate better nutritional status in this population.

Number of Days Hospitalized

Number of days hospitalized was also collected for each adolescent participant during the 6-month baseline and follow-up periods. Higher number of days hospitalized typically indicates poorer disease status.

Covariates

At baseline, participants reported on demographic information including age, gender, race/ethnicity, religious affiliation, household income, and age at diagnosis. Site of enrollment (Southeast vs. Midwest), intervention group, and use of disease-modifying medications [Kalydeco® (ivacaftor), Orkambi® (lumacaftor/ivacaftor)] at baseline were also recorded.

Analyses

Preliminary Analyses

All continuous variables were examined for outliers and normal distributions. Descriptive statistics were calculated and changes over time in each main variable were evaluated with paired samples t-tests. Bivariate relationships among variables were tested with t-tests and correlations. Associations between possible covariates and baseline coping variables were also assessed a priori utilizing bivariate correlations. In order to facilitate model convergence and ensure good model fit, the number of covariates included in the final model was limited only to variables significantly associated with the key variables. Given these associations, gender (predicting adaptive coping and days hospitalized), time since diagnosis (predicting negative religious/spiritual coping), use of disease-modifying medications (predicting FEV1% and days hospitalized), and enrollment site (predicting positive religious/spiritual coping and days hospitalized) were included in the final model. Importantly, intervention status was not related to any study variable when assessed via bivariate correlations and did not predict any outcomes when included in the main models (during a priori model testing).

Main Analyses

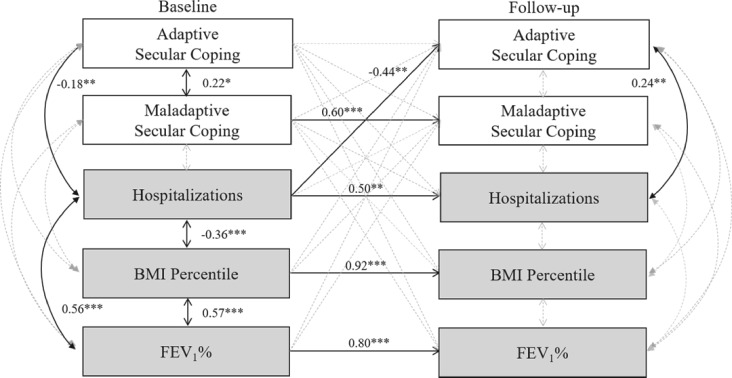

Prospective relations between adolescent coping styles (secular and religious/spiritual) and health indicators (FEV1%, BMI, days hospitalized) at baseline and follow-up were analyzed with autoregressive cross-lagged path models in Mplus version 7.11 (see Figures 1 and 2). To better understand reciprocal links specifically between coping styles and health indicators (rather than links between different coping styles) and to reduce model complexity, two separate autoregressive cross-lagged path models were conducted for secular vs. religious/spiritual coping (a priori). To further simplify the models and promote model convergence, cross-lagged links between health indicators were not included (a priori). The models included the stability of each variable over time and covariances among all variables measured at the same time point, as well as the cross-lagged links between each coping and health indicator variable over time. Fit of each model was assessed by evaluating the model chi-square (p-value > .05), the comparative fit index (CFI; CFI > 0.90), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI; TLI > 0.90), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR; SRMR < 0.08; Coovert & Craiger, 2000). Post hoc power analyses indicated sufficient power for each model (>0.80; MacCallum et al., 1996). Missing data (6% of all data points) were handled with full information maximum likelihood, which reduces bias and uses all available data points.

Figure 1.

Autoregressive cross-lagged path model displaying reciprocal links between secular coping strategies and health indicators over time. Note. Covariates are not included in this figure but are described in text.

Figure 2.

Autoregressive cross-lagged path model displaying reciprocal links between religious/spiritual coping strategies and health indicators over time. Note. Covariates are not included in this figure but are described in text.

Post Hoc Sensitivity Analyses

Post hoc sensitivity analyses were also completed to assess the stability of findings in subsets of participants. Specifically, models were rerun post hoc including only participants who identified as religious/spiritual (n = 71) and also without the religious/spiritual subscale (two items) on the Brief COPE to further distinguish between secular and religious/spiritual types of coping.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive analyses of the coping variables revealed seven outliers, each of which was truncated to a raw score corresponding to three standard deviations above or below the mean. The means and standard deviations of all variables—including physical health indicators—at baseline and follow-up are presented in Table II. Paired samples t-tests demonstrated no change in means overtime for any coping or health indicator variable. Adaptive forms of both coping styles (i.e., adaptive secular coping and positive religious/spiritual coping) were endorsed more frequently than their maladaptive counterparts (i.e., maladaptive secular coping and negative religious/spiritual coping) at both baseline and follow-up (all ps <.001). Zero-order correlations among coping variables and health indicators are presented in Table III. Absolute correlations among the four coping variables ranged from 0.02 to 0.43, and among the three health indicators from 0.22 to 0.59. Coping variables were not significantly correlated with health indicators.

Table II.

Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables.

| Variable | Baseline |

Follow-up |

t (df) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | ||

| Positive religious/spiritual coping | 1.50 (0.89) | 0.00–3.00 | 1.51 (0.96) | 0.00–3.00 | −1.21 (53) |

| Negative religious/spiritual coping | 0.40 (0.51) | 0.00–2.05 | 0.40 (0.46) | 0.00–1.82 | −1.13 (53) |

| Adaptive secular coping | 2.56 (0.54) | 1.00–3.63 | 2.62 (0.58) | 1.56–3.60 | −0.84 (55) |

| Maladaptive secular coping | 1.73 (0.41) | 1.08–3.50 | 1.67 (0.36) | 1.00–2.91 | 0.11 (55) |

| Days hospitalized (sum) | 10.29 (12.48) | 0.00–50.00 | 10.51 (14.70) | 0.00–62.00 | 0.68 (41) |

| BMI percentile | 46.82 (27.51) | 0.98–98.03 | 44.20 (30.81) | 0.32–94.89 | 0.82 (39) |

| FEV1 predicted | 87.16 (22.43) | 31.94–130.00 | 84.04 (28.31) | 26.50–180.25 | 1.09 (40) |

Table III.

Correlations Between Coping Variables and Health Indicators within Baseline and Follow-up Timepoints.

| Variables | Positive RS coping |

Negative RS coping |

Adaptive Sec coping |

Maladaptive Sec coping |

Hospitalizations | BMI percentile | FEV1 predicted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive RS coping | 1.0 | −0.08 | 0.40** | −0.08 | −0.10 | 0.17 | −0.03 |

| Negative RS coping | 0.02 | 1.0 | −0.41** | 0.34* | −0.05 | −0.26 | −0.19 |

| Adaptive Sec coping | 0.43*** | −0.03 | 1.0 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Maladaptive Sec coping | 0.10 | 0.30** | 0.22* | 1.0 | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.11 |

| Hospitalizations | −0.10 | 0.01 | −0.17 | −0.01 | 1.0 | −0.22 | −0.37* |

| BMI percentile | 0.04 | −0.13 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.38** | 1.0 | 0.52*** |

| FEV1 predicted | 0.12 | −0.14 | −0.02 | 0.12 | −0.57*** | 0.58*** | 1.0 |

Note. RS = religious/spiritual coping; Sec = secular coping; baseline correlations are presented below the diagonal; follow-up correlations are presented above the diagonal.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Main Analyses

Secular Coping Model

The autoregressive cross-lagged path model linking secular coping (adaptive and maladaptive) to health indicators across baseline and follow-up (see Figure 1) had excellent fit to the data [χ2 (16) = 19.718, p = .233; CFI = 0.973; TLI = 0.917; SRMR = 0.051]. More days hospitalized during the baseline period predicted lower levels of adaptive secular coping at follow-up (β = –0.44, p < .01, 95% CI −0.73 to −0.15). All coping variables and health indicators were stable over time (βs = 0.50–0.92, ps < .01), except for adaptive coping (β = 0.21, p = .083, 95% CI −0.03 to 0.45). Concurrently at baseline, adaptive, and maladaptive coping were positively associated (β = 0.22, p < .05, 95% CI 0.04–0.40). Also concurrently, adaptive coping was associated with the number of days hospitalized, first negatively at baseline (β = −0.18, p < .05, 95% CI −0.36 to −0.00) and then positively at follow-up (β = 0.24, p < .01, 95% CI 0.07–0.40).

Religious/Spiritual Coping Model

The model linking religious/spiritual coping (positive and negative) to health indicators across baseline and follow-up (see Figure 2) also had excellent fit to the data [χ2 (20) = 24.218, p = .233; CFI = 0.976; TLI = 0.935; SRMR = 0.050]. Lower FEV1% at baseline predicted higher levels of positive religious/spiritual coping at follow-up (β = −0.29, p < .01, 95% CI −0.49 to −0.09). Higher levels of negative religious/spiritual coping at baseline predicted less positive religious/spiritual coping (β = −0.18, p < .05, 95% CI −0.37 to 0.01) at follow-up. All coping variables and health indicators were stable over time (βs = 0.45–0.94, p < .05). Concurrently at follow-up, negative religious/spiritual coping was associated with fewer days hospitalized (β = −0.28, p < .05, 95% CI −0.54 to −0.02).

Covariates

Only one significant longitudinal association was identified between covariates and the coping and/or health variables: being female was related to higher levels of adaptive secular coping at follow-up.

Post Hoc Sensitivity Analyses

No differences were identified in cross-lagged paths of the secular coping model when analyses were rerun with only the subset of participants that identified as religious (n = 71). No novel paths emerged when only religious participants were included in the religious/spiritual coping model; however, one cross-lagged link between pulmonary functioning and positive religious/spiritual coping became nonsignificant (β = −0.21, p = .065). Results were identical when analyses were rerun in the secular coping model without the two-item religious/spiritual subscale.

Discussion

Building on a growing body of research linking secular and religious/spiritual coping to health outcomes in individuals with CF (Abbott et al., 2001; Grossoehme et al., 2013; Reynolds et al., 2014), this study examined longitudinal, bidirectional links between coping styles and health indicators in adolescents with CF. The results showed that health functioning predicted both higher and lower levels of coping over time. The reverse, however, was not true, with coping not predicting health functioning. Specifically, more frequent hospitalizations predicted lower levels of adaptive secular coping over time and poorer pulmonary functioning predicted higher levels of positive religious/spiritual coping over time. Concurrently at baseline, adaptive secular coping was negatively associated with the number of days hospitalized. Interestingly, adaptive secular coping and the number of days hospitalized were positively associated with one another at follow-up. Finally, after accounting for all baseline predictors, residual covariances at follow-up showed that negative religious/spiritual coping was related to fewer days hospitalized.

Secular Coping and Health Indicators

Partially consistent with our hypothesis, more frequent hospitalizations during the baseline period predicted lower use of adaptive secular coping strategies at follow-up. This finding suggests that hospitalization may interfere with one’s ability to utilize adaptive secular coping strategies over time. It is possible that a hospitalization physically limits the adaptive coping skills available to youth by limiting their access to peers, support systems, and activities they may enjoy (e.g., school, clubs, and social activities). Similarly, it is also possible that the disruption and isolation associated with frequent hospitalizations make it more difficult to utilize adaptive strategies such as positive reframing, planning, use of instrumental support, and humor. Future studies should utilize qualitative methods to better understand the mechanism underlying this relationship. Nevertheless, it may be important for healthcare providers to thoroughly assess coping among hospitalized youth and work with them to promote adaptive coping strategies. Existing interventions have successfully taught adaptive coping strategies to adolescents with CF (Davis et al., 2004); however, the current findings highlight the importance of utilizing interventions with hospitalized youth specifically and working to provide and teach adaptive strategies that can be utilized long-term, both during and after hospitalizations.

Interestingly, adaptive secular coping and the number of days hospitalized were also associated with one another concurrently at baseline and follow-up, although in different directions. At baseline, frequent hospitalizations were associated with lower levels of adaptive secular coping, again suggesting that hospitalizations might limit one’s ability to access adaptive coping skills. At follow-up, however, when adolescents were on average 18 months older, the reverse was true: frequent hospitalizations were associated with higher levels of adaptive secular coping. Although seeming counterintuitive at first, this finding may reflect the increasing resilience of some individuals with CF over time in response to hospitalizations (Mitmansgruber et al., 2016). In fact, despite the serious nature of the disease and high treatment burden, some studies show the similar quality of life in individuals with CF versus healthy controls (Koscik et al., 2005; Moise et al., 1987; Wahl et al., 2005b). Our results provide preliminary evidence that the link between greater adversity (i.e., more hospitalizations) and adaptive coping skills may change over time to reflect post-traumatic growth, in which the stress of a chronic illness leads to positive changes such as an appreciation for life, closer relationships, and emotional and spiritual growth (Barakat et al., 2006; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Similarly, it may reflect the mobilization of coping skills in response to the stress of hospitalization (Spirito et al., 1995). However, it will be important for future research to replicate these findings.

Religious/Spiritual Coping and Health Indicators

Longitudinal links were also identified between religious/spiritual coping styles and health indicators. First, contrary to our hypothesis, poorer pulmonary functioning at baseline predicted higher levels of positive religious/spiritual coping at follow-up. Importantly, this is consistent with the “religious coping mobilization” effect described by Pargament et al. (1998, p. 721), where poor physical health actually mobilizes higher levels of both positive and negative religious/spiritual coping. This finding is also consistent with the previous finding that physical health adversity may enhance coping strategies—specifically religious/spiritual coping—over time. Further, negative religious/spiritual coping was concurrently associated with the number of days hospitalized during the follow-up period, such that frequent hospitalizations were related to lower use of negative religious/spiritual coping strategies. Although the effect was of very small magnitude and requires replication, this may be further evidence that, among adolescents with CF, physical health difficulties may enhance one’s coping processes, either by promoting adaptive coping or, in this case, attenuating negative religious/spiritual coping. Future studies should replicate these findings and evaluate possible underlying mechanisms.

Body Mass Index and Coping

Of note, no significant paths were identified between BMI and coping. Further understanding of these null findings is warranted. Future research should specifically aim to understand possible links between BMI and coping separately for males and females, as lower BMI is perceived differently by gender among individuals with CF, with females actually preferring the slimmer build associated with CF while males prefer to be heavier and bigger (Abbott et al., 2006). It is also possible that the 18-month time period between surveys was not long enough to capture subtle changes in/associated with BMI. Only one study to our knowledge has identified changes in BMI associated with coping, finding an overall decline of two BMI percentile points per year over a 5-year period, which was slowed for individuals utilizing positive religious/spiritual coping (Reynolds et al., 2014). Given this extended time period, it is possible that our timeline (18 months, on average) was not an adequate length of time to capture changes in BMI. Future research should continue to investigate longitudinal associations between coping and BMI specifically while also considering potential underlying mechanisms including adherence to nutritional versus pharmacological recommendations, parent monitoring/supervision of treatment regimens, mood changes, and other psychopathology, etc.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study had several limitations that should be noted. First, although we were able to focus on one specific disease group (i.e., cystic fibrosis), recruiting a representative sample from both inpatient and outpatient settings, our sample was small and thus limited statistical power to test more complex models. Future studies should therefore replicate these findings and expand these models in larger samples. Similarly, the small sample size also limited the number of variables that could be included in these specific models. With a larger sample size, it would be valuable to understand how specific coping strategies—rather than composite subscales—relate to health outcomes and also to assess the role of moderating factors (e.g., psychosocial functioning, caregiver functioning, adherence, etc.) in these relations.

Next, it would be important to replicate the present findings in other illness populations. CF is a rather unique disease in that it is a genetic, chronic, progressive, and life-shortening illness with a heavy treatment burden; it would be important to understand the bidirectional relations between coping and health indicators in other populations such as youth with acute illness or injury, chronic but not life-shortening diseases, and/or diseases with later onset. Finally, despite being a two-site study, our sample was rather homogenous, specifically in regards to religious diversity (85% Christian denomination). Future studies should aim to understand the relationships between religious/spiritual coping and health outcomes in other religious groups.

Implications and Conclusions

Findings from the current study suggest that physical health functioning—for better and for worse—is more consistent in influencing coping over time than the reverse. These results highlight the importance of providing interventions specifically to hospitalized youth with CF, as more days spent hospitalized was linked with lower use of healthy and adaptive coping over time. Further, the findings suggest that poorer physical health, specifically poorer pulmonary functioning, may actually enhance adolescents’ religious/spiritual coping strategies rather than degrade them. This finding is consistent with the literature on post-traumatic growth and mobilization of coping, suggesting that positive changes can occur in the face of adversity and stress within the context of a chronic illness. The current study extends these concepts to a population of adolescents with CF and further documents the incredible resilience of these youth.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to CD (grant number 1450078) and the National Institutes of Health award to the Gregory Fleming James Cystic Fibrosis Research Center at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (grant number DK072482).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Abbott J., Dodd M., Gee L., Webb K. (2001). Ways of coping with cystic fibrosis: implications for treatment adherence. Disability and Rehabilitation, 23(8), 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott J., Morton A. M., Musson H., Conway S. P., Etherington C., Gee L., Fitzjohn J., Webb A. K. (2007). Nutritional status, perceived body image and eating behaviours in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), 26(1), 91–99. 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D. L., Flume P. A., Hardy K. K. (2001). Psychological functioning of adults with cystic fibrosis. Chest, 119(4), 1079–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat L. P., Alderfer M. A., Kazak A. E. (2006). Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31(4), 413–419. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92–100. 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas B. E., Connor-Smith J. K., Saltzman H., Thomsen A. H., Wadsworth M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127. 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas B. E., Jaser S. S., Dunn M. J., Rodriguez E. M. (2012). Coping with chronic illness in childhood and adolescence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(1), 455–480. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith J. K., Compas B. E., Wadsworth M. E., Thomsen A. H., Saltzman H. (2000). Responses to stress in adolescence: measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 976–992. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coovert M., Craiger P. (2000). An expert system for integrating multiple fit indices for structural equation models. New Review of Applied Expert Systems and Emerging Technologies, 6, 39– 56. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S., Weekes J. C., McGrady M. E., Rosenthal S. L., Yi M. S., Pargament K., Succop P., Roberts Y. H., Tsevat J. (2012). Spirituality and religiosity in urban adolescents with asthma. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(1), 118–131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9408-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (2017). Patient Registry 2016 Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. A., Quittner A. L., Stack C. M., Yang M. C. (2004). Controlled evaluation of the STARBRIGHT CD-ROM program for children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 29(4), 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill E. J., Dawson R., Sellers D. E., Robinson W. M., Sawicki G. S. (2013). Longitudinal trends in health-related quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis. Chest, 144(3), 981–989. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findler L., Shalev K., Barak A. (2014). Psychosocial adaptation and adherence among adults with CF: a delicate balance. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 57(2), 90–101. 10.1177/0034355213495922 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gee L., Abbott J., Conway S. P., Etherington C., Webb A. K. (2003). Quality of life in cystic fibrosis: the impact of gender, general health perceptions and disease severity. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, 2(4), 206–213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1569-1993(03)00093-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossoehme D. H., Szczesniak R., McPhail G. L., Seid M. (2013). Is adolescents' religious coping with cystic fibrosis associated with the rate of decline in pulmonary function? A preliminary study. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 19(1), 33–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08854726.2013.767083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hymovich D. P., Baker C. D. (1985). The needs, concerns and coping of parents of children with cystic fibrosis. Family Relations 34(1), 91–97. 10.2307/583761 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson N., Fitzgerald D., Singh-Grewal D., Hanson C. S., Craig J. C., Tong A. (2014). Children's experiences of cystic fibrosis: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics, 133(6), e1683-1697–e1697. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koscik R. L., Douglas J. A., Zaremba K., Rock M. J., Splaingard M. L., Laxova A., Farrell P. M. (2005). Quality of life of children with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatrics, 147(3), S64–68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum R. C., Browne M. W., Sugawara H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitmansgruber H., Smrekar U., Rabanser B., Beck T., Eder J., Ellemunter H. (2016). Psychological resilience and intolerance of uncertainty in coping with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, 15(5), 689–695. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2015.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moise J. R., Drotar D., Doershuk C. F., Stern R. C. (1987). Correlates of psychosocial adjustment among young adults with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 8(3), 141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K. I. (2002). Is religion nothing but …? Explaining religion versus explaining religion away. Psychological Inquiry, 13(3), 239–244. 10.1207/S15327965PLI1303_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K. I., Koenig H. G., Perez L. M. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 519–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K. I., Smith B. W., Koenig H. G., Perez L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37(4), 710–724. 10.2307/1388152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton S. M., Cavalli K. S., Pargament K. I., Nasr S. Z. (2002). Religious/spiritual coping in childhood cystic fibrosis: a qualitative study. Pediatrics, 109(1), E8–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds N., Mrug S., Britton L., Guion K., Wolfe K., Gutierrez H. (2014). Spiritual coping predicts 5-year health outcomes in adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, 13(5), 593–600. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2014.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph K. D., Dennig M. D., Weisz J. R. (1995). Determinants and consequences of children's coping in the medical setting: conceptualization, review, and critique. Psychological Bulletin, 118(3), 328–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki G. S., Sellers D. E., Robinson W. M. (2011). Associations between illness perceptions and health-related quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 70(2), 161–167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner E. A., Zimmer-Gembeck M. J. (2007). The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 119–144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A., Stark L. J., Gil K. M., Tyc V. L. (1995). Coping with everyday and disease-related stressors by chronically ill children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(3), 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staab D., Wenninger K., Gebert N., Rupprath K., Bisson S., Trettin M., Paul K. D., Keller K. M., Wahn U. (1998). Quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis and their parents: what is important besides disease severity? Thorax, 53(9), 727–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi R. G., Calhoun L. G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl A. K., Rustoen T., Hanestad B. R., Gjengedal E., Moum T. (2005. a). Living with cystic fibrosis: impact on global quality of life. Heart & Lung, 34(5), 324–331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl A. K., Rustøen T., Hanestad B. R., Gjengedal E., Moum T. (2005. b). Self-efficacy, pulmonary function, perceived health and global quality of life of cystic fibrosis patients. Social Indicators Research, 72(2), 239–261. 10.1007/s11205-004-5580-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]