Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a disease characterized by chronic inflammation and irreversible airway obstruction. Cigarette smoking is the predominant risk factor for developing COPD. It is well-known that the COPD is also strongly associated with an increased risk of developing lung cancer. Cigarette smoke contains elevated concentrations of oxidants and various carcinogens (e.g., tobacco-derived nitrosamines) that can cause oxidative and alkylating stresses, which can also arise from inflammation. However, it is surprising that, except for oxidative stress, little information is available on the burden of alkylating stress and the detoxification efficiency of tobacco-derived carcinogens in COPD patients. In this study, we used LC-MS/MS to measure the archetypical tobacco-specific carcinogenic 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), its major metabolite, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL), three biomarkers of oxidative stress (8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine, 8-oxoGua; 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine, 8-oxodGuo; 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine, 8-oxoGuo) and two biomarkers of alkylating stress (N7-methylguanine, N7-MeGua and N3-methyladenine, N3-MeAde), in the urine of smoking and non-smoking COPD patients and healthy controls. Our results showed that not only was oxidative stress significantly elevated in the COPD patients compared to the controls, but also alkylating stress. Significantly, levels of alkylating stress (i.e., N7-MeGua) were highly correlated with the COPD severity and not affected by age and smoking status. Furthermore, COPD smokers had significantly higher ratios of free NNAL to the total NNAL than control smokers, implying a lower detoxification efficiency of NNK in COPD smokers. This ratio was even higher in COPD smokers with stages 3-4 than in COPD smokers with stages 1-2. Taken together, our results demonstrated that the detoxification efficiency of tobacco-derived carcinogens (e.g., NNK) was associated with the pathogenesis and possibly the progression of COPD. In addition to oxidative stress, alkylating stress derived from chronic inflammation appears to be also dominant in COPD patients.

Keywords: COPD, oxidative DNA/RNA damage, inflammation, methylated DNA damage, NNK, NNAL

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major and increasing health burden and is currently the fourth leading cause of death worldwide [1]. It is characterized by persistent airflow limitation and is associated with lung inflammation and tissue destruction [2]. COPD results from an interaction between environmental exposures and genetic susceptibility [2]. Among the environmental exposures, cigarette smoking is the main cause of COPD, as appropriately 90% of COPD patients are smokers or ex-smokers [3]. Other exposures, such as air pollution and occupational exposure to dusts and fumes, might also increase the risk of developing COPD in non-smokers [4].

Tobacco smoking is a major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS), containing 1017 oxidizing molecules per puff [5]. Such exposure causes direct injury to airway epithelial cells leading to airway inflammation in which a variety of cells, including neutrophils, marcophages and lymphocytes, are involved [6]. Overwhelming ROS levels can lead to oxidative stress, resulting in damage to proteins, lipids and DNA, and triggering the development of pathological changes in the lungs of COPD patients [7, 8]. Indeed, numerous studies have demonstrated an increased oxidative burden in COPD patients (including both current smokers or ex-smokers) compared to healthy controls [1]. Various oxidative stress biomarkers have been employed to assess the presence of oxidative stress in COPD patients, including lipid peroxides, protein oxidation products, enzymatic antioxidant activity and oxidatively damaged DNA [9]. Among these biomarkers, oxidatively damaged DNA (e.g., a common biomarker 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine, 8-oxodGuo [10]) has attracted less attention compared to the other biomarkers. Furthermore, it has been reported that oxidatively generated damage to RNA occurs more frequently than DNA, in part due to RNA being mostly single stranded and therefore more easily accessible to ROS [11]. However, the measurement of oxidatively generated damage to RNA (e.g., a primary oxidation product of guanosine, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine, 8-oxoGuo) in the COPD patients is rarely reported in the literature.

COPD is an independent risk factor for lung carcinoma, particularly for squamous cell carcinoma, and lung cancer is up to five times more likely to occur in smokers with airflow obstruction than those with normal lung function [12]. Cigarette smoking can exert its genotoxic and carcinogenic effects via tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs). 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), is an important, tobacco-derived inducer of lung adenocarcinoma, and is formed by nitrosation of nicotine and its related tobacco alkaloids during the curing process, as well as being formed pyrosynthetically from nicotine during smoking [13]. In vivo, NNK is converted metabolically to 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL), which is also a potent pulmonary carcinogen [14]. NNAL can be detoxified by glucuronidation of NNAL (NNAL-Gluc) that is readily excreted in urine along with free NNAL [15, 16]. It has been reported that the measurement of urinary total NNAL (the sum of free NNAL and NNAL-Gluc) is an informative biomarker of NNK exposure, and separate analysis of free NNAL and NNAL-Gluc (e.g., ratio of free NNAL or NNAL-Gluc to total NNAL) may also provide useful information on the relative efficiency of NNAL detoxification in individual smokers [17-19]. NNK, NNAL and other tobacco nitrosamines (e.g., N-nitrosodimethylamine) are also well-known DNA alkylating agents. It has been established that the metabolic activation of these tobacco nitrosamines in target tissues can result in DNA alkylation (forming such adducts as N7-methylguanine, N7-MeGua and N3-methyladenine, N3-MeAde), as a consequence of alkylating stress [20]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies in the literature that measured NNK, NNAL and the resulting alkylated DNA damages in COPD patients.

In this study, we recruited 102 COPD patients and 113 healthy controls. Eight biomarkers were measured in urine, including three biomarkers of tobacco smoke exposure (cotinine, the major metabolite of nicotine, NNK and NNAL), three biomarkers of oxidative stress [8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoGua), 8-oxodGuo and 8-oxoGuo], and two biomarkers of alkylating stress (N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde). All the urinary biomarkers were analyzed using highly specific and sensitive isotope-dilution liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) methods established previously. By measuring these biomarkers, we aimed to investigate (a) whether the alkylating and oxidative stresses were increased in COPD patients compared with those of healthy controls; (b) whether the efficiency of NNAL detoxification (using the ratio of free NNAL to total NNAL) varied between the COPD smokers and control smokers; (c) the associations between alkylating/oxidative stresses and COPD severity and (d) the association between the efficiency of NNAL detoxification in COPD smokers and COPD severity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All solvents and salts were of analytical grade. Reagents were purchased from the indicated sources: 8-oxoGuo, N3-MeAde, NNK, NNAL, d3-NNK, d3-NNAL, and [13C, 15N2]-8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine ([13C, 15N2]-8-oxoGuo) were from Toronto Research Chemicals. Unlabeled 8-oxoGua, 8-oxodGuo, cotinine and β-glucuronidase (type IX-A, Escherichia coli) were from Sigma-Aldrich. N7-MeGua was from Merck. The internal standards, [15N5]-8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine ([15N5]-8-oxodGuo) and d3-N3-methyladenine (d3-N3-MeAde) were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. The d3-cotinine was from Cerilliant. The [15N5]-8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine ([15N5]-8-oxoGua) and [15N5]-N7-methylguanine ([15N5]-N7-MeGua) respectively, were synthesized as described previously [21, 22].

2.2. Participants and urine samples collection

This study was approved by both the Institutional Review Boards of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital and Changhua Christian Hospital in Taiwan. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. A total of 102 male COPD patients (including 60 current smokers and 42 non-smokers) were enrolled. A total of 113 healthy subjects (including 68 current smokers and 45 non-smokers) were recruited as controls. The non-smokers included both never-smokers and ex-smokers. For COPD patients, urine was collected during patient clinic visits at Changhua Christian Hospital. For healthy individuals, urine was collected while they had their health examinations and a mid-stream urine sample was collected. Urine samples from each subject were collected into a 15 mL polypropylene centrifuge tube, maintained at 4 °C during sampling, and stored at – 20 °C until analysis.

The chief presenting symptoms in COPD patients were shortness of breath and dyspnea on exertion. Every patient received a pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry test. The diagnosis of COPD was established according to the global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) criteria: the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), divided by forced vital capacity (FVC), is less than 70% at post-bronchodilator phase, and post-brochodilator FEV1 increase is less than 200 cc and 12% when compared to pre-brochodilator FEV1. COPD patients were further classified into four stages by the severity of airflow limitation based on the post-brochodilator FEV1 value; stage 1, mild (FEV1 ≥ 80% of predicted value), stage 2, moderate (FEV1 50% ≤ FEV1< 80% of predicted value), stage 3, severe (FEV1 30% ≤ FEV1 < 50% of predicted value), and stage 4, very severe (FEV1 < 30% of predicted value). Patients with coexisting symptoms/signs, including fever, pneumonia and lung mass, were excluded. Additional demographic information including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and smoking status was recorded.

2.3. Urinary analysis of cotinine, NNK and NNAL using LC-MS/MS

Prior to the urinary analysis of all the biomarkers, the stored urine samples were thawed at 37 °C for 15 min to release possible analytes from the precipitate [23].

Urinary cotinine, a major metabolite of nicotine, was used to validate self-reported smoking status in healthy controls and COPD patients, and was measured by an isotope-dilution LC-MS/MS method previously described by Hu et al. [24]. Non-smokers were defined as those who had urinary concentration less than 30 ng cotinine/mg creatinine, as defined elsewhere [25]. An Agilent 1100 series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Germany) interfaced with a 4000 QTRAP hybrid triple quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometer (SCIEX, USA) equipped with a Turbo V source was employed in this study. The samples were analyzed in the positive ion multiple reaction monitoring mode. The LOD of cotinine in urine was 30 pg/mL.

The urinary concentrations of NNK and NNAL were also determined using a validated LC-MS/MS method as described by Hu et al. [26]. The same online LC-MS/MS as above was employed. The limits of detection (LODs) in urine were 0.4 and 0.8 pg/mL for free NNAL and total NNAL, respectively.

2.4. Urinary analysis of biomarkers of nucleic acid methylation and oxidation using LC-MS/MS

Urinary N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde concentrations, respectively, were determined, using two previously described LC-MS/MS methods [22, 27]. The detection limits of the methods were 8.0 pg/mL and 35 pg/mL for N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde, respectively. Urinary concentrations of 8-oxoGua, 8-oxodGo and 8-oxoGuo were measured simultaneously using a previously reported LC-MS/MS method [23]. The LODs in urine were 30 pg/mL for 8-oxoGua, 2 pg/mL for 8-oxodGuo and 3 pg/mL for 8-oxoGuo. All of the urine samples were also analyzed for creatinine (Cr) using a validated HPLC-UV assay [28].

2.5. Statistical methods

Mean and SD were used to describe the distributions of age and BMI for the study subjects. Because the concentrations of urinary biomarkers were not normally distributed, geometric mean and 95% confidence interval were used to describe the distributions of urinary concentrations of cotinine, NNAL, methylated DNA damage and oxidatively damaged DNA and RNA. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the continuous variables among groups. Multiple linear regression models were used to investigate the relationship among urinary biomarkers after adjusting for other variables. The data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical package (SPSS, version 22).

3. Results

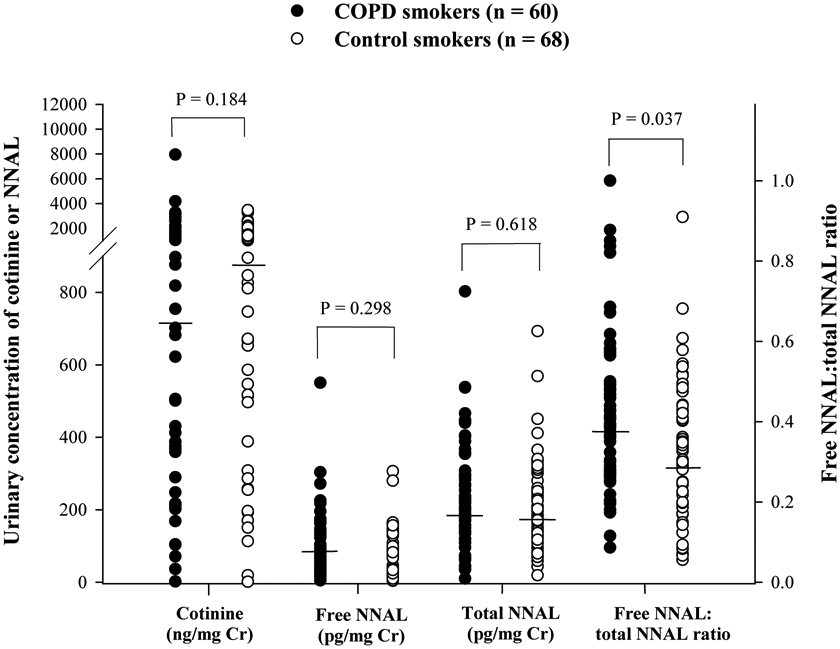

The participants characteristics are shown in Table 1. COPD patients had higher age and lower BMI than the healthy controls (including smokers and non-smokers). The smoking status of all the participants was obtained by questionnaire and was confirmed using the urinary cotinine levels. COPD non-smokers and control non-smokers all had cotinine levels less than 5 ng/mg Cr. In contrast, COPD smokers and control smokers had much higher urinary cotinine levels (geometric mean: 719 and 888 ng/mg Cr) than non-smokers, supporting their status of current smoking. There was no significant difference in urinary cotinine levels between COPD smokers and control smokers (see Figure 1, P = 0.184), indicating a similar level of exposure to tobacco smoke.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants.

| COPD patients (n = 102) |

Controls (n = 113) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Smokers (n = 60) |

Non-smokers (n = 42) |

Smokers (n = 68) |

Non-smokers (n = 45) |

| Age, years a | 63.1 ± 14.3 | 72.7 ± 7.4 | 55.4 ± 10.1 | 57.5 ± 3.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 a | 23.4 ± 4.4 | 23.9 ± 4.1 | 25.1 ± 3.7 | 25.4 ± 8.7 |

| Cotinine (ng/mg Cr) | 719b (483-1070) |

1.38 (0.99-1.93) |

888 (661-1193) |

1.69 (1.43-1.99) |

| Free NNAL (pg/mg Cr) | 71.6 (58.0-88.3) |

NDc | 52.8 (42.0-66.4) |

ND |

| Total NNAL (pg/mg Cr) | 184 (150-226) |

ND | 182 (157–211) |

ND |

| Free NNAL: total NNAL ratio | 0.37 (0.33-0.42) |

–d | 0.29 (0.25-0.34) |

– |

| N7-MeGua (μg/mg Cr) | 6.07 (4.46-8.27) |

6.22 (4.11-9.40) |

6.04** (5.71-6.40) |

5.20 (4.90-5.52) |

| N3-MeAde (ng/mg Cr) | 4.65* (3.73-5.79) |

3.19 (2.43-4.20) |

4.25** (3.43-5.26) |

2.09 (1.66-2.64) |

| 8-oxoGua (ng/mg Cr) | 15.2 (13.0-17.9) |

16.1 (13.3-19.6) |

13.2 (11.0-15.7) |

13.7 (11.3-16.5) |

| 8-oxodGuo (ng/mg Cr) | 4.28 (3.73-4.90) |

4.37 (3.71-5.15) |

3.96** (3.57-4.40) |

3.14 (2.78-3.55) |

| 8-oxoGuo (ng/mg Cr) | 7.74 (6.80-8.80) |

8.54 (7.43-9.82) |

5.67** (5.19-6.21) |

3.88 (3.44-4.37) |

Mean ± standard deviation.

Geometric mean (95% confidence interval).

Not detected.

Not available.

Statistical difference between smokers and non-smokers among COPD patients, by Mann-Whitney U test (P ≤ 0.005).

Statistical difference between smokers and non-smokers among controls, by Mann-Whitney U test (P ≤ 0.005).

Figure 1.

Distributions of cotinine, free NNAL, total NNAL and ratio of free NNAL/total NNAL in COPD smokers and control smokers. Each point represents an individual subject and the horizontal lines represent geometric mean values. The comparison was performed by Mann-Whitney U test.

Levels of NNK were not detected in all urine samples of the participants, probably due to its rapid metabolism to NNAL and other products [26, 29]. The levels of free NNAL and total NNAL (free NNAL plus NNAL-Gluc) were only detected in smokers. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, COPD smokers and control smokers had similar urinary concentrations of free NNAL and total NNAL. However, COPD smokers had a significantly higher ratio of free NNAL to total NNAL than control smokers (P = 0.037).

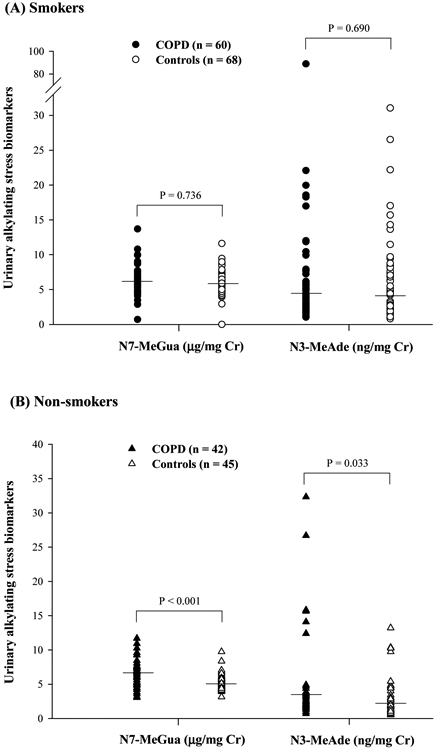

For the methylated DNA damage products, among the COPD patients, COPD smokers had a similar level of N7-MeGua as COPD non-smokers, but significantly higher level in N3-MeAde (P = 0.005). For the control subjects, smokers had significantly higher levels of N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde than non-smokers (P < 0.001 for both N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde, see Table 1). We further made a comparison between the COPD patients and control subjects, as illustrated in Figure 2. COPD smokers and control smokers had similar urinary excretions of N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde (Figure 2A), while COPD non-smokers had significantly higher urinary excretions of N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde than control non-smokers (P < 0.001 for N7-MeGua; P = 0.033 for N3-MeAde, see Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Distributions of alkylating stress biomarkers (N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde) in (A) smokers and (B) non-smokers. Each point represents an individual subject and the horizontal lines represent geometric mean values. The comparison was performed by Mann-Whitney U test.

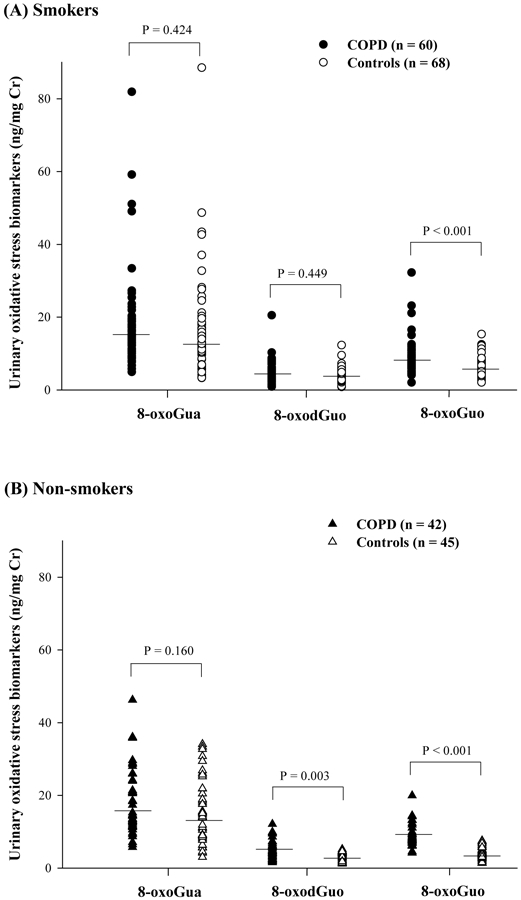

For the oxidized guanine products (see Table 1), there was no significant difference in the urinary levels of all three biomarkers between COPD smokers and COPD non-smokers. However, for the control subjects, smokers had higher urinary levels of 8-oxodGuo and 8-oxoGuo than non-smokers (P = 0.004 for 8-oxodGuo; P < 0.001 for 8-oxoGuo). When COPD patients were compared with control subjects, we noted that COPD smokers had higher levels of 8-oxoGuo only, compared to control smokers (P < 0.001, Figure 3A). Meanwhile, COPD non-smokers had higher levels of 8-oxodGuo and 8-oxoGuo than the control non-smokers (P = 0.003 for 8-oxodGuo and P < 0.001 for 8-oxoGuo, see Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Distributions of oxidative stress biomarkers (8-oxoGua, 8-oxodGuo and 8-oxoGuo) in (A) smokers and (B) non-smokers. Each point represents an individual subject and the horizontal lines represent geometric mean values. The comparison was performed by Mann-Whitney U test.

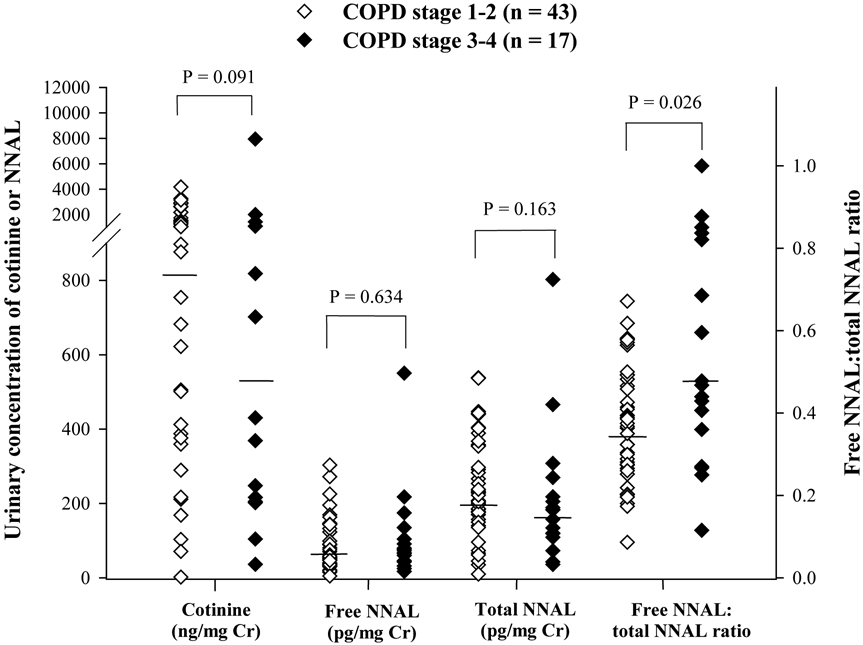

COPD patients were further sub-grouped into two groups according to their COPD severity; stages 1-2 (FEV1 ≥ 50%) vs. stages 3-4 (FEV1 < 50%). The urinary levels of various biomarkers were compared between the sub-groups. The results are illustrated in Figure 4 and summarized in Table 2. Interestingly, a significantly higher ratio of free NNAL to total NNAL was found in COPD smokers with stages 3-4, compared to COPD smokers with stages 1-2 (geometric mean: 0.47 vs. 0.34, P = 0.026).

Figure 4.

Distributions of cotinine, free NNAL, total NNAL and ratio of free NNAL/total NNAL in COPD smokers with stages 1-2 and stages 3-4 disease. Each point represents an individual subject and the horizontal lines represent geometric mean values. The comparison was performed by Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 2.

Urinary concentrations of various biomarkers in the COPD patients with different stages of disease.

| COPD smokers (n = 60) |

COPD non-smokers (n = 42) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Stages 1-2a (n = 43) |

Stages 3-4a (n = 17) |

Stages 1-2 (n = 27) |

Stages 3-4 (n = 15) |

| Age, year b | 60.7 ± 14.2 | 69.1 ± 13.0 | 73.4 ± 7.0 | 71.7 ± 8.0 |

| BMI, kg/m2 b | 23.8 ± 3.8 | 22.3 ± 5.7 | 25.1 ± 3.9 | 22.1 ± 3.7 |

| FEV1, % | 74.0c (70.1-78.2) |

37.8 (33.8-42.2) |

63.0 (59.8-66.2) |

38.6 (33.9-44.1) |

| FVC, % | 91.5 (87.1-96.2) |

58.3 (53.0-64.1) |

76.5 (71.8-81.5) |

59.7 (55.2-64.5) |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 63.2 (61.2-65.2) |

49.8 (44.5-55.8) |

60.7 (57.9-63.6) |

47.9 (42.1-54.6) |

| Cotinine (ng/mg Cr) | 812c (540-1221) |

527 (290-958) |

1.44 (0.89-2.33) |

1.28 (0.83-1.98) |

| Free NNAL (pg/mg Cr) | 66.0 (51.2-85.1) |

75.7 (51.0-112) |

ND d | ND |

| Total NNAL (pg/mg Cr) | 194 (153-246) |

161 (111-233) |

ND | ND |

| Free NNAL: total NNAL ratio | 0.34 (0.30-0.39) |

0.47* (0.36-0.62) |

–e | – |

| N7-MeGua (μg/mg Cr) | 5.63 (4.94-6.42) |

7.34 (5.52-9.77) |

5.88 (5.16-6.70) |

6.81 (6.07-7.64) |

| N3-MeAde (ng/mg Cr) | 4.91 (3.69-6.53) |

4.06 (3.21-5.15) |

3.20 (2.30-4.46) |

3.17 (1.95-5.16) |

| 8-oxoGua (ng/mg Cr) | 15.5 (13.2-18.2) |

14.6 (11.3-18.9) |

15.9 (13.2-19.1) |

16.6 (13.0-21.2) |

| 8-oxodGuo (ng/mg Cr) | 4.23 (3.66-4.90) |

4.38 (3.34-5.75) |

4.32 (3.59-5.22) |

4.44 (3.41-5.79) |

| 8-oxoGuo (ng/mg Cr) | 7.31 (6.47-8.26) |

8.93 (7.06-11.3) |

8.48 (7.42-9.69) |

8.64 (7.44-10.0) |

Stages 1-2: FEV1 ≥ 50%; stages 3-4: FEV1 < 50%.

Mean ± standard deviation.

Geometric mean (95% confidence interval).

Not detected.

Not available.

Statistical difference between stages 1-2 and stages 3-4, by Mann-Whitney U test (P < 0.05).

The correlations between urinary methylated DNA damage or oxidatively damaged DNA/RNA and COPD severity were assessed using Spearman rank correlation. The results showed that urinary N7-MeGua levels were highly positively correlated with COPD stage (n = 102; r = 0.279; P = 0.004, see Supplementary Figure S1), and negatively correlated with the FEV1/FVC ratio (r = −0.28; P = 0.004, see Supplementary Figure S2). No correlations were found between oxidatively damaged DNA or RNA and COPD severity. Multiple linear regressions revealed that the above correlations between urinary N7-MeGua and COPD stages or FEV1/FVC ratio were not affected by other variables (i.e., age and cotinine, P < 0.001).

4. Discussion

In this study, we report for the first time that: (1) the representative baseline of urinary levels of NNAL, methylated DNA damage, oxidatively damaged DNA/RNA in COPD patients as measured by LC-MS/MS; (2) the COPD smokers had higher ratios of free NNAL to total NNAL than the control smokers; (3) the higher COPD severity the higher ratio of free NNAL to total NNAL; (4) COPD non-smokers had increased alkylating and oxidative stress compared to the control non-smokers and (5) COPD severity was correlated with alkylating stress (N7-MeGua) and this correlation was not confounded by smoking status.

Cigarette smoking is the predominant cause of COPD and people with COPD have an increased risk (4- to 6-fold) of developing lung cancer [30-32]. These previous reports led us to investigate that whether the detoxification capacity of tobacco-specific carcinogens varied between COPD smokers and control smokers, as a potential, additional risk factor for COPD development. NNK is a well known tobacco-specific lung carcinogen found in tobacco products and tobacco smoke. NNK is metabolized by carbonyl reduction to its major carcinogenic metabolite NNAL, which is detoxified by glucuronidation at the nitrogen within the pyridine ring, or at the chiral alcohol to form glucuronide products [33]. As a result, the relationship between NNAL-Gluc products, free NNAL and total NNAL has been assessed to evaluate the detoxification capacity in smokers [34], and to investigate the risk of developing the certain cancers. For example, Chung et al. [35] reported that the NNAL-Gluc/free NNAL ratio is significantly associated with urothelial carcinoma risk, in a dose-response manner. Yuan et al. [36] showed that the NNAL-Gluc/free NNAL ratio is associated with a decreased risk of lung cancer, albeit this was not statistically significant. Our study revealed that the COPD smokers had a higher ratio of free NNAL/total NNAL than the control smokers, implying that the former had a worse ability to detoxify NNAL (lower detoxification potential).

It is not clear whether this observation in COPD smokers is “cause or effect”, i.e. a product of the pathological changes associated with COPD, or an initiating event. Interestingly, we further showed that the higher COPD severity is associated with a higher free NNAL/total NNAL ratio, again implicating diminished xenobiotic detoxification with worse COPD outcomes (see Figure 4). It is well established that NNK is a strong lung specific carcinogen and human lung is able to convert NNK to free NNAL, which is also a potent lung carcinogen [37]. Our finding might provide a clue that the degree of COPD severity was closely related to the development of lung cancer [38, 39].

NNK metabolism via α-methylene hydroxylation sequentially produces α-methylenehydroxy NNK, methane diazohydroxide, and methyldiazonium ion, each of which can react with DNA and yield N7-MeGua, O6-MeGua, N3-MeAde and O4-methylthymine adducts [40]. The N7 position of guanine and N3 position of adenine are the predominant reaction sites and both N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde have been proposed to be useful biomarkers of exposure to endogenous and exogenous alkylating agents such as nitrosamines. N3-MeAde is not only cytotoxic, but is also a premutagenic lesion, whereas N7-MeGua is not considered to be cytotoxic or premutagenic, but it is hydrolytically unstable, undergoing spontaneous depurination to produce apurinic sites and single strand breaks in DNA [41], and repair of single strand breaks is essential to the maintenance of genomic stability in mammalian cells [42]. A number of studies have shown that smoking is associated with significantly increased levels of N7-MeGua, reflecting the contribution of NNK to DNA adduct formation [26]. Indeed, our results showed that control smokers had significantly higher urinary levels of N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde than control non-smokers (P < 0.001, Table 1). For the COPD patients, although the N7-MeGua levels did not differ between COPD smokers and COPD non-smokers, N3-MeAde levels were significantly increased in COPD smokers (4.65 vs. 3.19 ng/mg Cr, P < 0.005). Furthermore, without smoking as a factor, we compared COPD non-smokers and control non-smokers for N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde levels. The results show that COPD non-smokers had significantly higher N7-MeGua and N3-MeAde than control non-smokers (Figure 2B). Interestingly, this study also demonstrated significant correlations between N7-MeGua and COPD severity (i.e., COPD stages or FEV1/FVC ratio). These findings might be explained by the chronic inflammation in COPD, which generates excessive not only the ROS, but also reactive nitrogen species (RNS, e.g., NO, NO2 and N2O3 [43]), and may further react with secondary aliphatic and aromatic amines to form N-nitroso carcinogens (e.g., N-nitrosodimethylamine), thereby increasing nitrosamine-derived alkylating stress [44]. Unfortunately, may lead to a vicious circle as these N-nitroso carcinogens could further stimulate oxidative stress and inflammation, promoting carcinogenesis [45].

Oxidative stress plays a central role in the progression of COPD [1]. Previously, several studies investigated the oxidative stress in COPD patients using 8-oxodGuo in urine or plasma as a biomarker. Igishi et al. [46] measured urinary 8-oxodGuo using ELISA in COPD patients in Japan and reported that urinary 8-oxodG level was increased in ex-smokers in the COPD group, compared with ex-smokers in the control group, and that urinary 8-oxodGuo was negatively correlated with FVC. Malic et al. [47] studied 71 COPD patients in Serbia using LC-MS/MS and found that COPD ex-smokers/smokers had higher urinary 8-oxodGuo than the control ex-smokers/smokers, and that 8-oxodGuo was correlated with COPD severity. In the present study, three biomarkers of oxidative stress showed no difference between COPD smokers and COPD non-smokers. In contrast, for the non-COPD controls, control smokers showed higher levels of urinary 8-oxodGuo and 8-oxoGuo than control non-smokers. Interestingly, we further demonstrated that only 8-oxoGuo levels differed between the COPD (including smokers and non-smokers) and non-COPD groups (Figure 3). This finding implies that 8-oxoGuo (a putative marker of RNA oxidation), rather than the more frequently measured 8-oxodGuo, exhibited a superior ability to discriminate the patients from the healthy subjects, compared to 8-oxodGuo or 8-oxoGua. Nevertheless, no correlation was observed between urinary 8-oxoGuo (or indeed 8-oxoGua and 8-oxodGuo) and COPD severity. This could be due to a limited sample size in this study, particularly for the COPD stage 3 and 4 (Table 2).

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that alkylating and oxidative stresses were significantly increased in COPD patients. In particular, the alkylating stress biomarker (N7-MeGua) was found to be correlated with COPD severity, which may highlight the involvement of RNS, derived from chronic inflammation, in COPD. The ratio of free NNAL/total NNAL was higher in COPD smokers than control smokers, and the ratio was also highly correlated with the COPD severity. This suggests that the capacity to detoxify tobacco-derived carcinogens (e.g., NNK) might play a mechanistic role in the development and progression of COPD, and hence represent an additional risk factor. However, some limitations of this study should be mentioned for consideration in future research. One is the small sample size for COPD patients with each stage, which could affect the statistical significance of the correlation. Secondly, other relevant biomarkers of RNS-induced damage (e.g., 3-nitrotyrosine and 8-nitroguanine) or epigenetics (e.g., 5-methylcytosine) could be included to further investigate the putative implication of lung carcinogenesis in COPD. Thirdly, although the lung is the main target of damaging effects of tobacco-derived carcinogens and COPD inflammation, the contribution of lung tissues to total urinary excretion of DNA/RNA biomarkers measured remains unknown. Despite the limitations of this study, these data help to elucidate the underlying mechanism of smoking-associated COPD, in addition to oxidative stress.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Alkylating and oxidative stresses were increased in COPD patients

Alkylating stress was correlated with COPD severity

Ratio of free NNAL/total NNAL were determined and increased in COPD smokers

The higher COPD severity the higher ratio of free NNAL/total NNAL

Cigarette smoke/chronic inflammation induced oxidative and alkylating stresses

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan [grant numbers NSC 99-2314-B-040-018-MY3, NSC 102-2314-B-040-016-MY3 and MOST 106-2314-B-040-015-MY3]. The research reported in this publication was also supported, in part, by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01ES030557. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- 8-oxodGuo

8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine

- 8-oxoGua

8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine

- 8-oxoGuo

8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- N3-MeAde

N3-methyladenine

- N7-MeGua

N7-methylguanine

- NNAL

4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol

- NNK

4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References:

- [1].McGuinness AJ, Sapey E, Oxidative Stress in COPD: Sources, Markers, and Potential Mechanisms, J. Clin. Med 6 (2017) 21–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Barnes PJ, Burney PG, Silverman EK, Celli BR, Vestbo J, Wedzicha JA, Wouters EF, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 1 (2015) 15076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kamal R, Srivastava AK, Kesavachandran CN, Meta-analysis approach to study the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among current, former and non-smokers, Toxicol. Rep 2 (2015) 1064–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Salvi S, Tobacco smoking and environmental risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Clin. Chest Med 35 (2014) 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pryor WA, Stone K, Oxidants in cigarette smoke. Radicals, hydrogen peroxide, peroxynitrate, and peroxynitrite, Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci 686 (1993) 12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zinellu E, Zinellu A, Fois AG, Carru C, Pirina P, Circulating biomarkers of oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review, Respir. Res 17 (2016) 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Boukhenouna S, Wilson MA, Bahmed K, Kosmider B, Reactive Oxygen Species in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev 2018 (2018) 5730395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kirkham PA, Barnes PJ, Oxidative stress in COPD, Chest 144 (2013) 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zinellu E, Zinellu A, Fois AG, Fois SS, Piras B, Carru C, Pirina P, Reliability and Usefulness of Different Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev 2020 (2020) 4982324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Poulsen HE, Weimann A, Henriksen T, Kjaer LK, Larsen EL, Carlsson ER, Christensen CK, Brandslund I, Fenger M, Oxidatively generated modifications to nucleic acids in vivo: Measurement in urine and plasma, Free Radic. Biol. Med 145 (2019) 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li Z, Wu J, Deleo CJ, RNA damage and surveillance under oxidative stress, IUBMB Life 58 (2006) 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Durham AL, Adcock IM, The relationship between COPD and lung cancer, Lung Cancer 90 (2015) 121–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Konstantinou E, Fotopoulou F, Drosos A, Dimakopoulou N, Zagoriti Z, Niarchos A, Makrynioti D, Kouretas D, Farsalinos K, Lagoumintzis G, Poulas K, Tobacco-specific nitrosamines: A literature review, Food Chem. Toxicol 118 (2018) 198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Balbo S, Johnson CS, Kovi RC, James-Yi SA, O'Sullivan MG, Wang M, Le CT, Khariwala SS, Upadhyaya P, Hecht SS, Carcinogenicity and DNA adduct formation of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and enantiomers of its metabolite 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol in F-344 rats, Carcinogenesis 35 (2014) 2798–2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen G, Luo S, Kozlovich S, Lazarus P, Association between Glucuronidation Genotypes and Urinary NNAL Metabolic Phenotypes in Smokers, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 25 (2016) 1175–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kozlovich S, Chen G, Watson CJW, Blot WJ, Lazarus P, Role of l- and d-Menthol in the Glucuronidation and Detoxification of the Major Lung Carcinogen, NNAL, Drug Metab. Dispos 47 (2019) 1388–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Carmella SG, Akerkar SA, Richie JP Jr., Hecht SS, Intraindividual and interindividual differences in metabolites of the tobacco-specific lung carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) in smokers' urine, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 4 (1995) 635–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yuan JM, Knezevich AD, Wang R, Gao YT, Hecht SS, Stepanov I, Urinary levels of the tobacco-specific carcinogen N'-nitrosonornicotine and its glucuronide are strongly associated with esophageal cancer risk in smokers, Carcinogenesis 32 (2011) 1366–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Park SL, Carmella SG, Ming X, Vielguth E, Stram DO, Le Marchand L, Hecht SS, Variation in levels of the lung carcinogen NNAL and its glucuronides in the urine of cigarette smokers from five ethnic groups with differing risks for lung cancer, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 24 (2015) 561–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Peterson LA, Context Matters: Contribution of Specific DNA Adducts to the Genotoxic Properties of the Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamine NNK, Chem. Res. Toxicol 30 (2017) 420–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hu CW, Chao MR, Sie CH, Urinary analysis of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine by isotope-dilution LC-MS/MS with automated solid-phase extraction: Study of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine stability, Free Radic. Biol. Med 48 (2010) 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chao MR, Wang CJ, Yang HH, Chang LW, Hu CW, Rapid and sensitive quantification of urinary N7-methylguanine by isotope-dilution liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry with on-line solid-phase extraction, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 19 (2005) 2427–2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shih YM, Cooke MS, Pan CH, Chao MR, Hu CW, Clinical relevance of guanine-derived urinary biomarkers of oxidative stress, determined by LC-MS/MS, Redox Biol. 20 (2019) 556–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hu CW, Chang YZ, Wang HW, Chao MR, High-throughput simultaneous analysis of five urinary metabolites of areca nut and tobacco alkaloids by isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry with on-line solid-phase extraction, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 19 (2010) 2570–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hansen AM, Garde AH, Christensen JM, Eller N, Knudsen LE, Heinrich-Ramm R, Reference interval and subject variation in excretion of urinary metabolites of nicotine from non-smoking healthy subjects in Denmark, Clin. Chim. Acta 304 (2001) 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hu CW, Hsu YW, Chen JL, Tam LM, Chao MR, Direct analysis of tobacco-specific nitrosamine NNK and its metabolite NNAL in human urine by LC-MS/MS: evidence of linkage to methylated DNA lesions, Arch. Toxicol 88 (2014) 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hu CW, Lin BH, Chao MR, Quantitative determination of urinary N3-methyladenine by isotope-dilution LC-MS/MS with automated solid-phase extraction, Int. J. Mass Spectrom 304 (2011) 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yang YD, Simultaneous determination of creatine, uric acid, creatinine and hippuric acid in urine by high performance liquid chromatography, Biomed. Chromatogr 12 (1998) 47–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Xia Y, McGuffey JE, Bhattacharyya S, Sellergren B, Yilmaz E, Wang L, Bernert JT, Analysis of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol in urine by extraction on a molecularly imprinted polymer column and liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure ionization tandem mass spectrometry, Anal. Chem 77 (2005) 7639–7645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Parris BA, O'Farrell HE, Fong KM, Yang IA, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and lung cancer: common pathways for pathogenesis, J. Thorac. Dis 11 (2019) S2155–S2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Balla MM, Desai S, Purwar P, Kumar A, Bhandarkar P, Shejul YK, Pramesh CS, Laskar S, Pandey BN, Differential diagnosis of lung cancer, its metastasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on serum Vegf, Il-8 and MMP-9, Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 36065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Raviv S, Hawkins KA, DeCamp MM Jr., Kalhan R, Lung cancer in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: enhancing surgical options and outcomes, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 183 (2011) 1138–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kozlovich S, Chen G, Watson CJW, Lazarus P, Prominent Stereoselectivity of NNAL Glucuronidation in Upper Aerodigestive Tract Tissues, Chem. Res. Toxicol 32 (2019) 1689–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Carmella SG, Akerkar SA, Richie JP Jr., Hecht SS, Intraindividual and interindividual differences in metabolites of the tobacco-specific lung carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) in smokers' urine, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 4 (1995) 635–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chung CJ, Lee HL, Yang HY, Lin P, Pu YS, Shiue HS, Su CT, Hsueh YM, Low ratio of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol-glucuronides (NNAL-Gluc)/free NNAL increases urothelial carcinoma risk, Sci. Total Environ 409 (2011) 1638–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yuan JM, Nelson HH, Carmella SG, Wang R, Kuriger-Laber J, Jin A, Adams-Haduch J, Hecht SS, Koh WP, Murphy SE, CYP2A6 genetic polymorphisms and biomarkers of tobacco smoke constituents in relation to risk of lung cancer in the Singapore Chinese Health Study, Carcinogenesis 38 (2017) 411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hecht SS, Tobacco smoke carcinogens and lung cancer, J. Natl. Cancer Inst 91 (1999) 1194–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Carr LL, Jacobson S, Lynch DA, Foreman MG, Flenaugh EL, Hersh CP, Sciurba FC, Wilson DO, Sieren JC, Mulhall P, Kim V, Kinsey CM, Bowler RP, Features of COPD as Predictors of Lung Cancer, Chest 153 (2018) 1326–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sekine Y, Katsura H, Koh E, Hiroshima K, Fujisawa T, Early detection of COPD is important for lung cancer surveillance, Eur. Respir. J 39 (2012) 1230–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yalcin E, de la Monte S, Tobacco nitrosamines as culprits in disease: mechanisms reviewed, J. Physiol. Biochem 72 (2016) 107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Fu D, Calvo JA, Samson LD, Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents, Nat. Rev. Cancer 12 (2012) 104–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Caldecott KW, DNA single-strand break repair and spinocerebellar ataxia, Cell 112 (2003) 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ichinose M, Sugiura H, Yamagata S, Koarai A, Shirato K, Increase in reactive nitrogen species production in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease airways, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 162 (2000) 701–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].d'Ischia M, Napolitano A, Manini P, Panzella L, Secondary targets of nitrite-derived reactive nitrogen species: nitrosation/nitration pathways, antioxidant defense mechanisms and toxicological implications, Chem. Res. Toxicol 24 (2011) 2071–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fishbein A, Hammock BD, Serhan CN, Panigrahy D, Carcinogenesis: Failure of resolution of inflammation?, Pharmacol. Ther In press (2020) 107670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Igishi T, Hitsuda Y, Kato K, Sako T, Burioka N, Yasuda K, Sano H, Shigeoka Y, Nakanishi H, Shimizu E, Elevated urinary 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, a biomarker of oxidative stress, and lack of association with antioxidant vitamins in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Respirology 8 (2003) 455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Malic Z, Topic A, Francuski D, Stankovic M, Nagorni-Obradovic L, Markovic B, Radojkovic D, Oxidative Stress and Genetic Variants of Xenobiotic-Metabolising Enzymes Associated with COPD Development and Severity in Serbian Adults, COPD 14 (2017) 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.