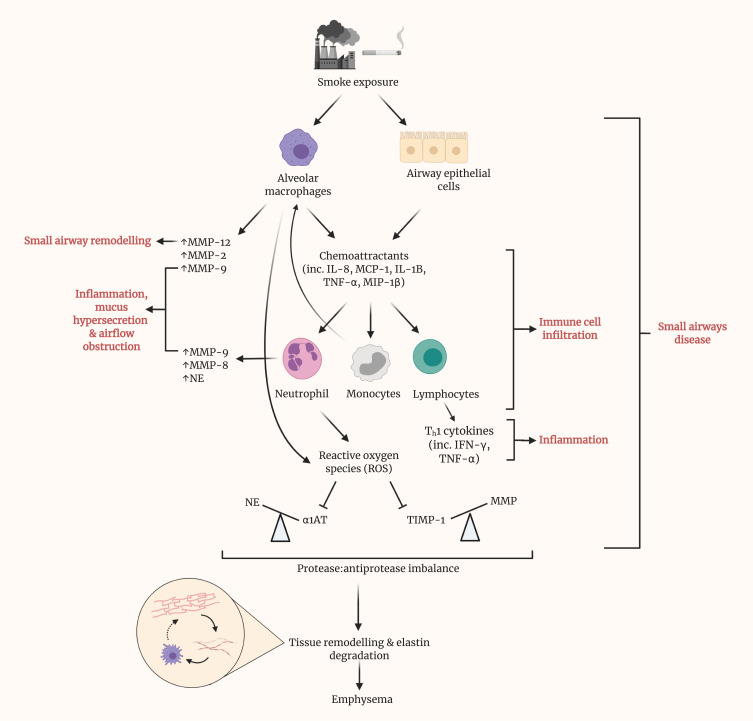

Figure 3.

Prolonged smoke exposure initiates various pathways, resulting in disease of the small airways and eventuating in the onset of emphysema. Upon exposure to smoke, both alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells within the small airways release various chemoattractants, including interleukin (IL)-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, IL-1B, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β. These, in turn, recruit neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes and promote their infiltration of the small airways. Alongside alveolar macrophages, neutrophils are a source of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) within the lungs. MMPs have been shown to contribute to several of the phenotypic changes in SAD, namely remodeling, inflammation, mucus hypersecretion and airflow obstruction. Recruited monocytes differentiate into macrophages, contributing almost to a positive feedback loop. Lymphocytes represent a major source of cytokines, particularly Th1 cytokines such as IFN-γ, which contribute greatly to local inflammation. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by neutrophils inhibits the action of antiprotease, alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT), thus causing an imbalance with its cognate protease, neutrophil elastase. Similarly, the antiprotease activity of TIMPs is hindered by ROS. By result, a large imbalance is observed, in favor of protease activity. Cumulatively, these prior pathways culminate in tissue remodeling and elastin degradation within the alveoli, leading to emphysema. Elastin fibers, as liberated by elastin degradation, activate alveolar macrophages.