Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic evaluation of community-based participatory research (CBPR) interventions on diabetes outcomes. Understanding of effective CBPR interventions on diabetes outcomes is limited, and findings remain unclear.

Methods

A reproducible search strategy was used to identify studies testing CBPR interventions to improve diabetes outcomes, including A1C, fasting glucose, blood pressure, lipids, and quality of life. Pubmed, PsychInfo, and CINAHL were searched for articles published between 2010 and 2020. Using a CBPR continuum framework, studies were classified based on outreach, consulting, involving, collaborating, and shared leadership.

Results

A total of 172 were screened, and a title search was conducted to determine eligibility. A total of 16 articles were included for synthesis. Twelve out of the 16 studies using CBPR approaches for diabetes interventions demonstrated statistically significant differences in 1 or more diabetes outcomes measured at a postintervention time point. Studies across the spectrum of CBPR demonstrated statistically significant improvements in diabetes outcomes.

Conclusions

Of the 16 studies included for synthesis, 14 demonstrated statistically significant changes in A1C, fasting glucose, blood pressure, lipids, and quality of life. The majority of studies used community health workers (CHWs) to deliver interventions across group and individual settings and demonstrated significant reductions in diabetes outcomes. The evidence summarized in this review shows the pivotal role that CHWs and diabetes care and education specialists play in not only intervention delivery but also in the development of outward-facing diabetes care approaches that are person- and community-centered.

Diabetes is the 7th leading cause of death worldwide and affects approximately 422 million people globally.1 According to the WHO Global Report on diabetes, prevalence has nearly doubled in the past 3 decades.1 Diabetes is associated with a number of comorbid conditions and is the leading cause of kidney failure and lower limb amputations.2 Risk factors for diabetes complications include obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, high blood pressure and cholesterol, and high blood glucose. In 2017, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that more than 15% of US adults had an A1C greater than 9% and 73% of US adults had high blood pressure.2 Diabetes and the associated complications disproportionately affect marginalized populations and communities worldwide, including low-income communities and ethnic minority populations.2

Risk reduction and avoiding diabetes complications require knowledge, skills, and resources for effective self-management as well as integrated care with a diabetes management care team.1,3–5 However, many communities at risk for poor diabetes outcomes have limited resources and access to such integrated care, with even less having access to a culturally tailored diabetes care plan.6–8 A growing body of evidence suggests the need for large-scale community-based interventions for diabetes management.2 Although community-based interventions have been used for reducing risk of diabetes, such as the widely adopted Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), efforts are increasing to adapt community-based risk reduction models for the management of diabetes care using a community-based participatory orientation for intervention delivery.9,10

Community-Based Participatory Research

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a collaborative approach to research that engages the community as coresearchers and facilitates a colearning process.11 Traditional clinical research identifies a problem area, recruits participants, evaluates an intervention or makes observations, analyzes data, then disseminates findings throughout the scientific community.12 CBPR approaches, however, center the community around identifying areas for intervention, defining the problem, and generating potential solutions.11 Additionally, findings are often disseminated throughout both the participating community and the scientific community. Through this level of engagement, the research design is enriched by harnessing the strength of both researcher and community partner.11

There are several core principles that characterize CBPR, including (1) participatory, (2) cooperative, (3) colearning, (4) systems development, (5) empowerment, (6) balance, and (7) dissemination. Participatory includes engagement of the community across the research process, including study design, implementation, and analysis. For CBPR to be cooperative, the investigative team often works collaboratively to adapt to the needs of the community with a goal for equal contribution and ongoing feedback. Colearning involves placing an emphasis on a shared learning experience as collaboration is established and progresses. Systems development results as capacity within the community is built through the research process and facilitates the empowerment of the community through shared decision-making. Finally, as the collaboration and colearning evolves, a balance of research and action is achieved where findings can then be disseminated, and further action steps may be established as result.11,13

Although CBPR approaches are characterized by core principles, the methodology is often used on a continuum that ranges from highly participatory to primarily researcher driven, or outreach versus shared leadership.14 This continuum includes the following categories: out-reach, consulting, involving, collaborating, and shared leadership.14 A distinguishing factor of each approach is the communication that occurs in the research process and the level of involvement and decision-making. Referring to the McCloskey et al14 continuum, outreach as a CBPR approach is largely unidirectional in communication and focuses on establishing channels for communication.14 Consulting as an approach that utilizes an answer-seeking style of communication, and although still unidirectional, greater levels of inputs are often provided.14 Moving down the continuum to involving shifts to bidirectional styles of communication with the establishment of partnerships.14 Collaborating and shared leadership approaches are characterized as bidirectional styles of communication but also foster trust through integration of community partners into the research development process as well as implementation. This is followed by dissemination of research results and action plans for further program development.14

Taken together, CBPR as a methodology has implications for improving the health of marginalized populations who suffer disproportionate burdens of disease and poor health outcomes.11,13,15–22 However, systematic evaluation of the effectiveness of CBPR interventions on diabetes outcomes remains unclear. As the diabetes burden worsens across communities and populations worldwide, understanding the effectiveness of CBPR interventions on diabetes outcomes may inform the development of outward-facing interventions that are community-centered to address this burgeoning public health crisis. Although traditional methods of clinical research are warranted, approaching the increasing diabetes burden across populations necessitates a population health approach to build capacity to effect change over time. The purpose of this article is to conduct a systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions using CBPR methods for diabetes outcomes (blood glucose, cholesterol, blood pressure, and quality of life) in adults with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Information Sources, Eligibility Criteria, and Search

PRISMA guidelines were used to conduct this review. Eligibility criteria were established following a PICO framework (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes) with inclusion and exclusion criteria established by all 3 authors a priori. A reproducible search strategy was used to identify studies meeting eligibility criteria for studies testing lifestyle interventions using CBPR methods for diabetes outcomes among adults with type 2 diabetes. Three databases were used to identify studies: Pubmed, PsychInfo, and CINAHL. The search included studies published between 2010 and 2020. Rationale for this date restriction was to maximize applicability to practice by providing an up-to-date summary of evidence by including interventions that were conducted within the past 10 years. Studies were included if they were available in English and were conducted in an adult population age 18 years and older. Medical Subject Heading terms for diabetes, lifestyle interventions, and CBPR were used. Refer to Supplementary Material for the list of all terms.

The inclusion criteria used for this review included the following: (1) published in English; (2) adult population at least 18 years of age; (3) lifestyle intervention conducted in patients with type 2 diabetes; (4) study fit on the continuum of CBPR based on McCloskey et al14 framework; (5) at least 1 of the following diabetes outcomes were measured and reported in findings—A1C, fasting glucose, lipids, blood pressure, quality of life; and (6) a lifestyle intervention being evaluated for its impact on 1 or more of the clinical outcomes listed above and had to report at least 2 time points (baseline and follow-up). A decision was made a priori to include lifestyle interventions that were single-group quasi-experimental as well as randomized controlled trials with 1 or more comparison group. Studies looking at diabetes prevention were excluded, as were patients with gestational and type 1 diabetes and prediabetes. Studies that examined both patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes were included for synthesis, and results were reported for the subgroup population with type 2 diabetes. Results of each study were listed on a continuum of CBPR as defined by McCloskey et al14 ranging from community outreach to shared leadership. Studies were determined to fall on the CBPR continuum by 2 of the authors (JAC and LEE). The methods of each study were carefully reviewed and placed on the continuum using McCloskey et al14 definitions of each approach and were classified based on the studies’ description of community involvement and decision-making. Clinical outcomes were selected based on the established literature demonstrating the effectiveness of interventions to minimize diabetes complications and burden of disease when targeted.23,24

Study Selection and Data Collection

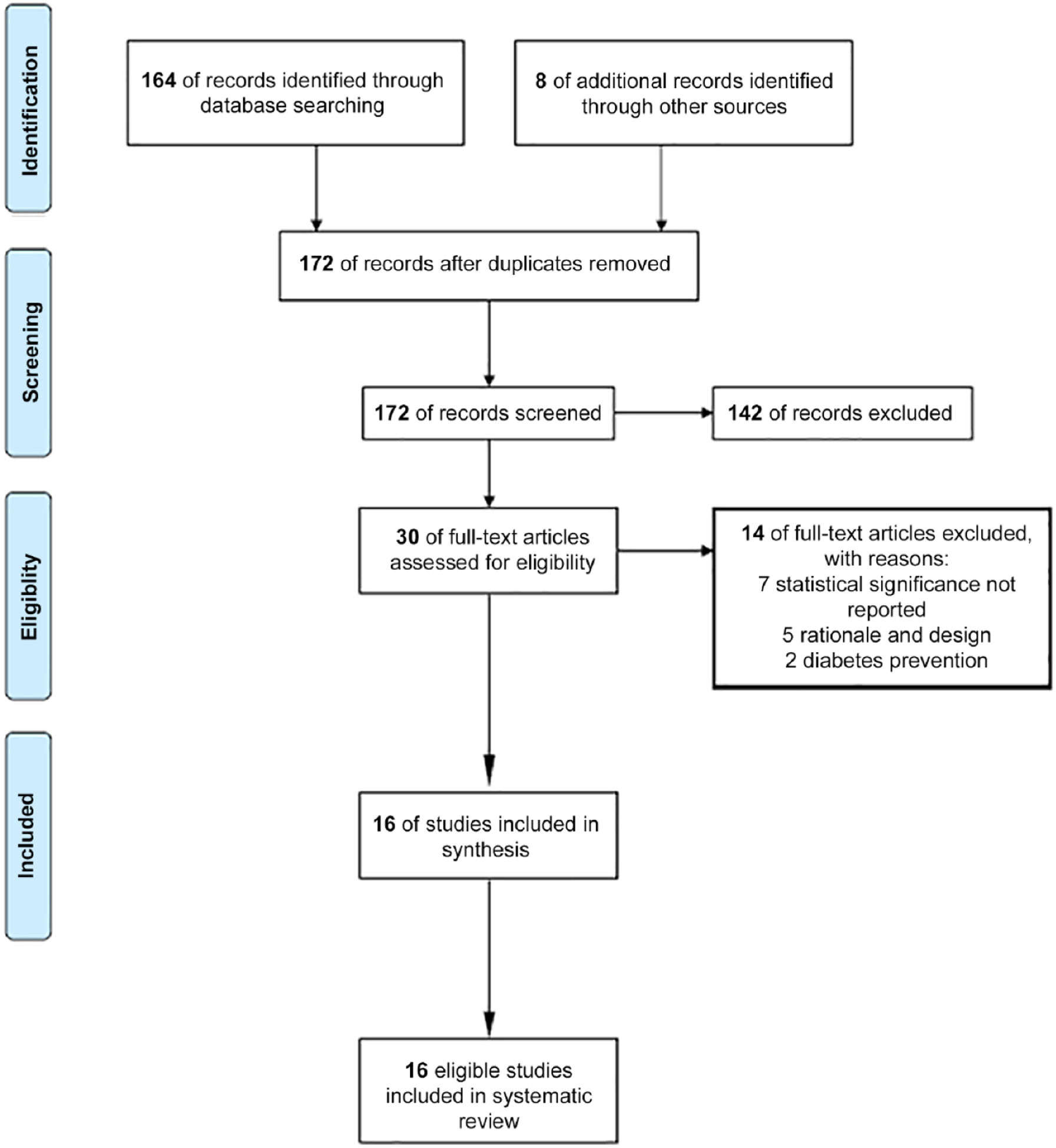

This systematic review used PRISMA guidelines for process and identification of eligible studies as seen in Figure 1. The process for study selection included systematic review of titles followed by abstracts. During the title and subsequent abstract review, each study was evaluated using a checklist of study eligibility criteria and excluded if not met. Following the abstract review, the remaining articles were included for full-text synthesis. If upon synthesis articles were found to not meet the criteria, they were excluded. For example, if outcome measures did not include values but rather a report of measurement, they were excluded. Similarly, if upon synthesis studies did not fall on the continuum for CBPR, studies were excluded. The final list of eligible studies was synthesized, and data were extracted (Table 1). Data extraction included the intervention evaluated, population, setting, impact on 1 or more of the outcomes and whether statistical significance was demonstrated, CBPR method used, and country the study was conducted in. The revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials was used to assess data quality of randomized trials,25 and the JBI critical appraisal checklist for nonrandomized studies was used to assess data quality for nonrandomized studies.26

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram.

Table 1.

Summary of Articles

| Article | Study Design | Objective | No. Participants | Sample Population | Setting | Impact on Outcome | CBPR Method | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balagopal et al27 | Quasi-experimental (single group) | Test the effectiveness of a CBPR approach to diabetes prevention and management using culturally tailored DPP delivered by CHWs | 1638 (diabetes subgroup = 116) | Adults age ≥18 y dwelling in the rural community of Vadodara, Gujarat | Community sites in Vadodara, Gujarat. | Among community members with diabetes, at 6-mo follow-up, there was a −6.21 (P < .001) change in SBP, −0.167 (P < .001) change in DBP, and a −19.08 (P < .001) change in FG | Shared leadership | India |

| Chesla et al28 | Quasi-experimental (single group) | Test effectiveness of culturally tailored coping skills training for type 2 diabetes led by work social workers/health educators | 178 | Chinese immigrants with type 2 diabetes | Community site | Significant changes were found in postmeasurements of diabetes quality of life. No change in A1C was found. | Shared leadership | US |

| Freeman et al29 | Quasi-experimental (single group) | Test the effectiveness of a multifaceted skills and education training (Taking Control of Type 2 Diabetes) for self-management and risk reduction among rural adults with type 2 diabetes | 115 | Rural adults with type 2 diabetes | Local clinic/YMCA | Significant changes were observed in mean A1C from baseline to 6 mo with a 2.1 drop (P < .001), maintained through 12 mo. | Shared leadership | US |

| Harrison et al30 | Quasi-experimental (single group) | Test the effectiveness of a community wellness lifestyle program including diet, physical activity, and behavioral skills for improvement in health-related quality of life and diabetes outcomes | 319 (diabetes subgroup = 46) | Adults age ≥18 y | Community wellness center | Among community members with diabetes, at 12-wk follow-up, significant reduction in LDL was demonstrated, −6.8 (P < .05). Improvements were seen in health-related quality of life for physical functioning (P < .05), mental health (P < .001), physical health summary (P < .001), and mental health summary (P < .05). | Consult | US |

| Heisler et al31 | Randomized controlled trial (2 group: intervention and control) | Test effectiveness of culturally tailored diabetes decision aid on diabetes management delivered via tablet led by CHWs | 198 | Adults with type 2 diabetes age ≥21 y with A1C greater than 7.5% | Community sites | Significant changes were found at 3 mo in A1C for those in intervention (−0.4, P = .001) and control (−0.3, P = .016). No between-group differences. | Shared leadership | US |

| Islam et al32 | Quasi-experimental (single group) | Test the effectiveness and feasibility of a culturally tailored CHW-led lifestyle intervention on diabetes management | 26 | Bangladeshi immigrants with type 2 diabetes age 21–85 y | Clinic and community sites | No significant changes were found at follow-up for A1C. | Shared leadership | US |

| Kim et al33 | Randomized controlled trial (2 group: intervention and control) | Test the effectiveness of a culturally tailored RN- and CHW-led lifestyle modification intervention on diabetes management | 250 | Korean American immigrants ≥35 y with diabetes and A1C of at least 7.0% | Community site | Statistically and clinically significant changes from baseline A1C were observed in the intervention group (P < .001). Statistically significant changes in A1C were observed between the intervention and control groups (P < .01). | Collaborate | US |

| Lutes et al34 | Randomized controlled trial (2 group: intervention and control) | Test the effectiveness of using a CHW-led lifestyle intervention on diabetes outcomes | 200 | Rural African American women with type 2 diabetes, age 19–75 y | Community organizations; telephone | No differences were found between the intervention group and control group for reduction in A1C or BP control. When comparing participants who were on oral medication vs insulin, those on oral medication showed marginally significant reduction in A1C by −0.70 (P = .05). | Consult | US |

| Lynch et al35 | Randomized controlled trial: (2 group: intervention and control) | Test effectiveness of peer-led, group-based lifestyle intervention to improve diabetes management | 61 | African Americans with type 2 diabetes ≥18 y | Community based park building; telephone | No differences were found between the intervention group and the control group for A1C, BP, or lipids. | Outreach | US |

| McElfish et al36 | Quasi-experimental (single group) | Test the effectiveness of family-based diabetes self-management education | 27 | Marshallese adults with diabetes and their family members | Home or community site | Percent change in A1C from baseline was observed at postintervention; however, statistical significance not observed. | Shared leadership | us |

| Mehuys et al37 | Randomized controlled trial: (2 group: intervention and control) | Test effectiveness of a pharmacist-led diabetes education and counseling to improve diabetes outcomes and management | 288 | Adults with type 2 diabetes age 45–75 y | Community based pharmacy | Intervention group showed significant reduction in A1C, intervention −0.6%, P < .001. Significant decrease in FG (P < .001) but not between groups. | Outreach | Belgium |

| Mendenhall et al38 | Quasi-experimental (single group) | Test the effectiveness of a family education diabetes series on diabetes management | 36 | American Indian adults with type 2 diabetes | Community site | Statistically significant change in A1C was observed from baseline to 3 mo (6.99–6.53, P < .05). Statistically significant changes were observed for SBP and DBP at 3 mo (P < .05, P < .01). | Shared leadership | US |

| Perez-Escamilla et al39 | Randomized controlled trial: (2 group: intervention and control) | Test effectiveness of a CHW-led, culturally tailored lifestyle intervention for diabetes management delivered in person in the patient’s home | 211 | Latino adults with type 2 diabetes age ≥21 y | Home; community clinic | The intervention group showed significant reductions in A1C at 3 mo (−0.42% P < .05), at 6 mo (−0.47%, P = .05), at 12 mo (−0.57%, P < .05), and at 18 mo (−0.55%, P < .05). Statistical differences were observed for FG (P < .05). No difference in BP or lipids was observed. | Collaborate | US |

| Spencer et al40 | Randomized controlled trial: (2 group: intervention and control) | Test the effectiveness of using CHWs as health advocates for lifestyle intervention using group-based education, 1-on-1 home visits, and clinic support for diabetes management | 183 | African American and Latino adults with type 2 diabetes | Community site | Statistically significant change in A1C was observed for the intervention group at 6 mo, −0.8 (P < .01). Significant improvements in cholesterol were also observed at 6 mo for the intervention group. No significant change in BP was observed. | Shared leadership | US |

| West-Pollak et al41 | Quasi-experimental (single group) | Test effectiveness of community leaders trained as CHWs to lead group lifestyle modification intervention for diabetes delivered in community setting | 76 | Community members with A1C ≥6.5%, indicating diabetes. or between 5.7% and 6.4%, indicating prediabetes | Community organization | An overall decrease in A1C by −0.49% was observed at 6 mo. An overall decrease in both SBP, −11.9 mmHg, and DBP, −11.8 mmHg, was also observed at 6 mo. Impact on outcomes were statistically significant at 12 mo. | Collaborate | Dominican Republic |

| Yazdanpanah et al42 | Quasi-experimental (single group) | Test the effectiveness of group nutrition and physical activity education in a subgroup of adults with diabetes and family members | 320 | Subgroup of adults with diabetes age 30–65 y | Community site | Statistically significant changes in A1C (6.9–6.1, P < .001), cholesterol (238.9–208.7, P < .001), and fasting glucose (176–102, P < .01) were observed postintervention. No significant changes in blood pressure. | Shared leadership | Iran |

Abbreviations: A1C, hemoglobin A1C; BP, blood pressure; CHW, community health worker; CBPR, community-based participatory research; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DPP, diabetes prevention program; FG, fasting glucose; LDL, low density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure; YMCA, Young Men’s Christian Association.

Results

Study Selection

The search results are shown in Figure 1. Records identified through Pubmed, PsychInfo, and CINAHL returned 164 articles. A hand search was then conducted that included 8 additional articles, resulting in a total of 172 articles for screening. A title and abstract search was conducted for the 172 articles to determine eligibility based on the aforementioned categories. The title and abstract review resulted in 30 full-text articles for full-text review. Two authors (JAC, LEE) participated in the search and selection of studies for inclusion and assessment of quality. Discordance in study selection was evaluated across all authors, and 1 author (LEE) made the final decision for inclusion.

After conducting the full-text review, 14 additional articles were eliminated with reasons stated in Figure 1. Sixteen eligible articles were included in this final review. Using McCloskey et al’s14 continuum of CBPR, 2 studies were classified as outreach, 2 studies were classified as consult, 3 studies were classified as collaborate, and 9 studies were classified as shared leadership. No studies included in this review met the definition of involve.

Study Characteristics and Outcomes of Studies

Table 1 summarizes the results of each study that met eligibility criteria. Of the 16 interventions, 9 were quasi-experimental with a single study group, and 7 were randomized controlled trials. All studies measured outcomes on at least 2 time points. There was a wide range of sample sizes, from 26 to 320. Twelve studies were conducted in the US.28–36,38–40 Four studies were conducted outside the US in the following countries: Belgium,37 Dominican Republic,41 India,27 and Iran.42 When looking at each study by community setting, 11 studies were conducted in a local community site,28,30,31,33–35,38,40–42 1 study was conducted in a community pharmacy,37 2 studies were conducted at a community clinic,29,32 and 2 studies were conducted in the home or a community site based on participant availability.36,39 Additionally, Table 1 summarizes the type of intervention that was conducted as well as the impact on outcomes. All 16 interventions included a lifestyle/behavioral modification component such as skills, education, and coping strategies for diabetes management.

Table 2 summarizes each study by CBPR method and outcome with the statistical significance observed. Fourteen of the 16 studies measured A1C as a primary outcome.28,29,31–41,42 Nine studies measured blood pressure (BP) as an outcome.33–35,38–42 Six studies measured lipids as an outcome.30,33,36,39,40,42 Five studies measured fasting glucose as an outcome,27,30,37,39,42 and 3 measured quality of life (QOL) as an outcome.28,30,33 Of the 14 studies measuring A1C, 9 demonstrated statistically significant reduction in A1C.29,31,33,37–42 Of the 9 studies measuring BP, 3 demonstrated statistically significant improvements in BP.27,38,41 Three of the 6 studies measuring lipids demonstrated statistically significant improvements in lipids,30,40,42 and 4 of the 5 studies measuring fasting glucose demonstrated statistically significant improvements in fasting glucose.27,37,39,42 All 3 studies measuring QOL as an outcome demonstrated statistically significant improvements in QOL.28,30,33

Table 2.

CBPR Method by Outcome Measures of Studies Meeting Inclusion Criteriaa

| Outcome Measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article | CBPR Method | A1C | FG | BP | Lipids | QOL |

| Balagopal et al27 | Shared leadership | X* | X* | |||

| Chesla et al28 | Shared leadership | X | X* | |||

| Freeman et al29 | Shared leadership | X* | ||||

| Harrison et al30 | Consult | X | X* | X* | ||

| Heisler et al31 | Shared leadership | X* | ||||

| Islam et al32 | Shared leadership | X | ||||

| Kim et al33 | Collaborate | X* | X | X* | X* | |

| Lutes et al34 | Consult | X | X | |||

| Lynch et al35 | Outreach | X | X | |||

| McElfish et al36 | Shared leadership | X | X | |||

| Mehuys et al37 | Outreach | X* | X* | |||

| Mendenhall et al38 | Shared leadership | X* | X* | |||

| Pérez-Escamilla et al39 | Collaborate | X* | X* | X | X | |

| Spencer et al40 | Shared leadership | X* | X | X* | ||

| West-Pollak et al41 | Collaborate | X* | X* | |||

| Yazdanpanah et al42 | Shared leadership | X* | X* | X | X* | |

Abbreviations: A1C, hemoglobin A1C; BP, blood pressure; CBPR, community-based participatory research; FG, fasting glucose; QOL, quality of life.

Bold

indicates statistical significance found postintervention.

Table 3 summarizes each study by intervention delivery modality and statistical significance observed. Seven studies used community health workers (CHWs) as intervention delivery mode.27,31,32,34,39,40,41 The 7 studies using CHWs as the primary mode of delivery used a combination of in-person group sessions, individual sessions, telephone sessions, and tablet sessions.27,31,32,34,39,40,41 Two studies used CHWs combined with nurse facilitation33 and with a diabetes educator.36 The term diabetes educator is used in this results section to reflect the studies that used and specified inclusion of Certified Diabetes Educators (CDEs). The updated term, diabetes care and education specialist, will be used in the discussion to discuss current implications of findings. The CHW and nurse combined delivery met primarily in groups as well as at the individual level,33 whereas the CHW combined with a diabetes educator met with family members and the patients in the patients’ home.36 Seven studies used a multidisciplinary team.30,35,38 This included health care professionals such as a pharmacist,37 CDEs,28,29 or dietician for intervention delivery.42

Table 3.

Intervention Modality by Outcome Measures of Studies Meeting Inclusion Criteriaa

| Outcome Measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article | Intervention Modality | A1C | FG | BP | Lipids | QOL |

| Balagopal et al27 | CHW led—group & individual | X* | X* | |||

| Chesla et al28 | Social worker/health educators—group | X | X* | |||

| Freeman et al29 | Hospital staff & DM life coach—group | X* | ||||

| Harrison et al30 | Multidisciplinary care team—group & individual | X | X* | X* | ||

| Heisler et al31 | CHW led—individual & tablet | X* | ||||

| Islam et al32 | CHW led—group | X | ||||

| Kim et al33 | CHW & RN led—group & individual | X* | X | X* | X* | |

| Lutes et al34 | CHW led—telephone | X | X | |||

| Lynch et al35 | Multidisciplinary care team—group | X | X | |||

| McElfish et al36 | CDE & CHW—family group in home | X | X | |||

| Mehuys et al37 | Pharmacist led—individual in pharmacy | X* | X* | |||

| Mendenhall et al38 | Multidisciplinary care team & community leaders—group | X* | X* | |||

| Pérez- Escamilla et al39 | CHW led—individual in home | X* | X* | X | X | |

| Spencer et al40 | CHW led—group & individual | X* | X | X* | ||

| West-Pollak et al41 | CHW led—group | X* | X* | |||

| Yazdanpanah et al42 | Dietician led—group | X* | X* | X | X* | |

Abbreviations: A1C, hemoglobin A1C; BP, blood pressure; CHW, community health worker; DM, Diabetes; FG, fasting glucose; QOL, quality of life

Bold

indicates statistical significance found postintervention.

Discussion

This is among one of the first systematic syntheses evaluating the use of CBPR methods in lifestyle interventions for diabetes outcomes among adults with type 2 diabetes. Using a reproducible search strategy, 16 studies were identified that fell on a continuum of CBPR methodology ranging from community outreach to shared leadership. Of the 16, 12 demonstrated improvement in 1 or more diabetes outcomes across the CBPR continuum, suggesting that intervention effectiveness may be achieved across levels of CBPR engagement. When evaluating the studies based on the CBPR continuum, the majority of studies utilized a shared leadership approach to develop and implement a diabetes lifestyle intervention. This study adds to the literature in 2 key ways. First, using the CBPR framework of engagement developed by McCloskey et al,14 this review provides a summary of evidence for effective diabetes lifestyle interventions across diverse community populations and settings. Second, this review provides a summary of evidence by intervention delivery for diabetes lifestyle interventions across diverse community populations and settings.

Summary of Evidence by CBPR Approach

More than half of the studies included in this review utilized a shared leadership approach.27–29,31,32,36,38,40,42 Shared leadership is the highest level of engagement within the CBPR continuum,14 emphasizing bidirectional communication to establish trust and capacity for improving community-wide health. Of the studies utilizing a shared leadership approach for diabetes lifestyle interventions, 7 studies demonstrated statistically significant improvements in 1 or more diabetes outcomes.27–29,31,38,40,42 The next level of engagement on the continuum that uses bidirectional communication is the collaborative approach. The collaborative approach emphasizes the building of relationships and high involvement without shared decision making.14 Three studies utilized a collaborative approach,33,39,41 of which all 3 showed statistically significant improvements in A1C as an outcome measure postintervention. The consult approach and the outreach approach were the other categories found among studies included in this review. Both are unidirectional forms of communication with minimal involvement in community decision-making.14 The emphasis in both consult and outreach approaches is on establishing community connection.14 Two studies utilized a consult approach,30,34 and only 1 of the 2 demonstrated significant improvements in lipids and quality of life.30 Two studies utilized an outreach approach,35,37 with both measuring A1C as an outcome; however, only 1 found statistical significant improvements in A1C.37

Summary of Evidence by Intervention Delivery

When looking at intervention by delivery, of the 7 studies using CHWs for intervention delivery, 5 showed a change in 1 or more diabetes outcome.27,31,39,40,41 Of the 5 interventions demonstrating a change in diabetes outcome, those that were conducted in groups and at the individual level demonstrated significant changes in diabetes outcomes. Two of the CHW-led interventions utilized a telehealth approach for intervention delivery.31,34 The Heisler et al31 intervention was a randomized controlled trial with an intervention and control group. The intervention group received culturally tailored diabetes education delivered by a CHW via a tablet, and the control group received printed materials.31 Both groups had initial in-person visits with 2 follow-up telephone sessions that included goal setting and navigation of challenges. Significant improvements were found at 3 months postintervention for A1C for the intervention group. The control group also showed a significant reduction in A1C at 3 months postintervention.31 The Lutes et al34 intervention was also a randomized controlled trial with an intervention and control group. The intervention group received telephone-delivered diabetes education for 16 weeks delivered by a CHW, compared to the control group, who received paper-based material in the mail.34 No significant changes were seen at follow-up for either the intervention or control group. However, patients taking oral medication compared to those taking insulin showed significant reduction in A1C postintervention compared to those on oral medication in the control group.34 Of interest, Heisler et al31 utilized a shared leadership approach in CBPR for the intervention development and conducted the study among an urban, inner-city population,31 whereas Lutes et al34 utilized a consult approach to CBPR and conducted the study among a rural population.34 Although both studies utilized a telehealth approach delivered by CHWs, the level of CBPR engagement for intervention development may be an important consideration for incorporating the patients’ lived experiences and perceived needs for diabetes interventions across populations.

Of the 5 studies that used a multidisciplinary team for intervention delivery, the Lynch et al35 intervention was primarily led by a registered dietitian and a peer supporter who provided social support via the telephone weekly.35 Group intervention sessions were held weekly for 2 hours for 16 weeks. Session frequency was decreased over time using a phased approach over an 18-month period.35 No statistically significant changes in diabetes outcomes were observed across postintervention time points. The CBPR approach utilized for this intervention is consistent with an outreach approach where communication is more unidirectional.14

Of the 2 studies that combined CHWs with either a nurse or CDE only, the CHW and nurse combined intervention showed statistically significant differences in diabetes outcomes at the postintervention time point,33 including change in A1C, lipids, and QOL. The McElfish et al36 intervention was developed as a family model approach to diabetes management and took place with individuals with diabetes and their families within the family home among a Pacific Islander population.36 Diabetes education was delivered by a CDE, and a community health worker served to translate the information in real time during the intervention delivery for individuals who needed translation.36 At the post-follow-up assessment, participants showed no significant changes in diabetes outcomes.35

For studies that were pharmacist led and dietician led, both showed significant reductions in diabetes outcomes postintervention.37,42 Mehuys et al37 developed a community pharmacist-led intervention wherein pharmacists provided real-time diabetes education for participants when refilling diabetes medications.37 The diabetes education included knowledge about diabetes, proper medication use, knowledge about complications, and recommendations for diet and physical activity.37 Patients received this information at every refill visit for 6 months. This intervention group was compared to a control group who received usual pharmacist care. At the postintervention follow-up, the intervention group demonstrated significant reductions in A1C and fasting glucose compared to the control group. The Yazdanpanah et al42 intervention consisted of single-group diabetes education classes led by a dietitian twice a week for 4 weeks and included instruction and group exercise activities.42 At the postintervention follow-up, participants showed significant reductions in A1C, fasting glucose, and lipids.42

Limitations

There are 3 main limitations to this study that warrant consideration. First, the search conducted in this study was limited to articles published in English. Therefore, articles testing a diabetes intervention using CBPR methods may have been excluded from this search due to the language criteria. Second, this article only includes studies that were published, and therefore results may contain some bias if CBPR studies examining diabetes interventions were not published due to nonsignificant findings. Third, this study is considered narrative, and no statistical methods were used to determine statistical significance and therefore cannot speak to any causal relationships or any statistical differences in CBPR approach used.

Implications and Relevance for Diabetes Care and Education Specialists

Although standard models specific to CBPR are greatly needed,43,44 the studies summarized here demonstrate that diabetes interventions can effectively be carried out across the continuum of CBPR with significant impact on diabetes outcomes. Additionally, the evidence summarized in this review shows the pivotal role that CHWs and diabetes care and education specialists play in not only intervention delivery but also in the development of outward-facing diabetes care approaches that are person- and community-centered. Overall, 12 out of the 16 studies using CBPR approaches for diabetes interventions demonstrated statistically significant differences in 1 or more outcome measured at a postintervention time point.

Future studies should consider meta-analysis to determine statistically significant differences in CBPR approach across the continuum of engagement. Additionally, the central role of CHWs and diabetes care and education specialists in intervention development using a CBPR approach warrants further consideration as well as population of interest for understanding effective strategies for CBPR interventions for diabetes management.

Supplementary Material

Funding Source:

This article was partially supported the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (K24DK093699, R01DK118038, R01DK120861, principal investigator: Egede) and Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment (principal investigator: Egede). Funding organizations had no role in the analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of the article.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no competing financial interests exist.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Diabetes. Accessed May 5, 2020 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes

- 2.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report. Published 2017. Accessed May 5, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

- 3.American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(suppl 1):S55–S64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association. 15. Diabetes advocacy: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41 (suppl 1):S152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. 4. Lifestyle management: standards of medical care in diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care. 2018; 41(suppl 1):S38–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nam S, Janson SL, Stotts NA, Chesla C, Kroon L. Effect of culturally tailored diabetes education in ethnic minorities with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27(6): 505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawthorne K, Robles Y, Cannings-John R, Edwards AG. Culturally appropriate health education for type 2 diabetes in ethnic minority groups: a systematic and narrative review of randomized controlled trials. Diabet Med. 2010;27(6):613–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawthorne K, Robles Y, Cannings-John R, Edwards AG. Culturally appropriate health education for type 2 diabetes mellitus in ethnic minority groups. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD006424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De las Nueces D, Hacker K, DiGirolamo A, Hicks LS. A systematic review of community-based participatory research to enhance clinical trials in racial and ethnic minority groups. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 Pt 2):1363–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Diabetes Prevention and Control. The community guide. Published 2017. Accessed May 5, 2020 https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/What-Works-Factsheet-Diabetes.pdf

- 11.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady DG, Newmann TB. Designing Clinical Research. 4th ed. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCloskey DJ, McDonald M, Cook J, et al. Community engagement: defining and organizing concepts from the literature In: Principles of Community Engagement. 2nd ed. National Institutes of Health; 2011:341. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, eds. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, Wilson N. Improving health through community organization and community building In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Jossey-Bass; 2008:287–312. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hacker K. Community-Based Participatory Research. SAGE Publications, Inc; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Sayu RP, Sparks SM. Factors that facilitate addressing social determinants of health throughout community-based participatory research processes. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2017; 11(2):119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dodani S. Community-based participatory research approaches for hypertension control and prevention in churches. Int J Hypertens. 2011;2011:273120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gehlert S, Coleman R. Using community-based participatory research to ameliorate cancer disparities. Health Soc Work. 2010; 35(4):302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horowitz CR, Goldfinger JZ, Muller SE, et al. A model for using community-based participatory research to address the diabetes epidemic in East Harlem. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008;75(1):13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. a consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018;41:2669–2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl. 1):S1–S212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Methods Cochrane. RoB2: a revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials. Published 2019. Accessed August 31, 2019 https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/current-version-of-rob-2

- 26.Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Systematic reviews of effectiveness In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. Accessed August 31, 2019 https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/MANUAL/Chapter3%3ASystematicreviewsofeffectiveness [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balagopal P, Kamalamma N, Patel TG, Misra R. A community-based participatory diabetes prevention and management intervention in rural India using community health workers. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(6):822–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chesla CA, Chun KM, Kwan CM, et al. Testing the efficacy of culturally adapted coping skills training for Chinese American immigrants with type 2 diabetes using community-based participatory research. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36(4):359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeman K, Hanlon M, Denslow S, Hooper V. Patient engagement in type 2 diabetes: a collaborative community health initiative. Diabetes Educ. 2018;44(4):395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison RL, Mattson LK, Durbin DM, Fish AF, Bachman JA. Wellness in community living adults: the Weigh to Life program. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(2):270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heisler M, Choi H, Palmisano G, et al. Comparison of community health worker-led diabetes medication decision-making support for low-income Latino and African American adults with diabetes using e-health tools versus print materials: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10 suppl): S13–S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Islam NS, Wyatt LC, Patel SD, et al. Evaluation of a community health worker pilot intervention to improve diabetes management in Bangladeshi immigrants with type 2 diabetes in New York City. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39(4):478–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim MT, Kim KB, Huh B, et al. The effect of a community-based self-help intervention: Korean Americans with type 2 diabetes. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(5):726–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lutes LD, Cummings DM, Littlewood K, Dinatale E, Hambidge B. A community health worker-delivered intervention in African American women with type 2 diabetes: a 12-month randomized trial. Obesity. 2017;25(8):1329–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch EB, Liebman R, Ventrelle J, Avery EF, Richardson D. A self-management intervention for African Americans with comorbid diabetes and hypertension: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McElfish PA, Bridges MD, Hudson JS, et al. Family model of diabetes education with a Pacific Islander community. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41(6):706–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehuys E, Van Bortel L, De Bolle L, et al. Effectiveness of a community pharmacist intervention in diabetes care: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36(5):602–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mendenhall TJ, Berge JM, Harper P, et al. The Family Education Diabetes Series (FEDS): community-based participatory research with a midwestern American Indian community. Nurs Inq. 2010; 17(4):359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pérez-Escamilla R, Damio G, Chhabra J, et al. Impact of a community health workers-led structured program on blood glucose control among Latinos with type 2 diabetes: the DIALBEST trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(2):197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spencer MS, Rosland AM, Kieffer EC, et al. Effectiveness of a community health worker intervention among African American and Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):2253–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West-Pollak A, Then EP, Podesta C, et al. Impact of a novel community-based lifestyle intervention program on type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk in a resource-poor setting in the Dominican Republic. Int Health. 2014;6(2):118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yazdanpanah B, Safari M, Yazdanpanah S, et al. The effect of participatory community-based diabetes cares on the control of diabetes and its risk factors in western suburb of Yasouj, Iran. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(5):794–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen PG, Diaz N, Lucas G, Rosenthal MS. Dissemination of results in community-based participatory research. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(4):372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delafield R, Hermosura AN, Ing CT, et al. A community-based participatory research guided model for the dissemination of evidence-based interventions. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2016;10(4):585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.