Abstract

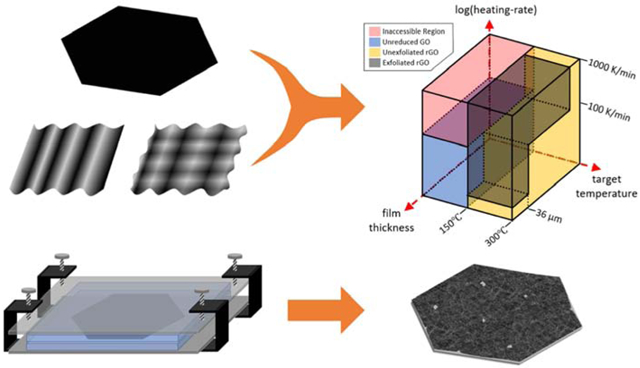

Thermal exfoliation is an efficient and scalable method for the production of graphene nanosheets or nanoplatelets, which are typically re-assembled or blended to form new macroscopic “graphene-based materials”. Thermal exfoliation can be applied to these macroscopic graphene-based materials after casting to create internal porosity, but this process variant has not been widely studied, and can easily lead to destruction of the physical form of the original cast body. Here we explore how the partial thermal exfoliation of graphene oxide (GO) multilayer nanosheet films can be used to control pore structure and electrical conductivity of planar, textured, and confined GO films. The GO films are shown to exfoliate explosively when the instrument-set heating rates are 100 K/min and above leading to complete destruction of the film geometry. Textured films with engineered micro-wrinkling and crumpling show similar thermal behavior to planar films. Here, we also demonstrate a novel method to produce fairly large size intact rGO films of high electrical conductivity and microporosity based on confinement. Sandwiching GO precursor films between inert plates during partial exfoliation at 250°C produces high conductivity and porosity material in the form of a flexible film that preserves the macroscopic structure of the original cast body.

Keywords: Planar, textured, and confined graphene nanosheet films; Partial thermal exfoliation

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Porous graphene-based materials hold great potential for a wide variety of applications in fields such as energy storage, selective membranes, semi-conductors and catalysis, if they are effectively produced and engineered with tuned properties [1-9]. The graphene oxide (GO) is a convenient precursor for graphene-based materials but many common processing methods leads to layer stacking and dramatic loss of specific surface area [10]. In many applications it is also desirable to deoxygenate the GO precursor to reduced graphene oxide (rGO). Among the various deoxygenation techniques that include chemical [11], electrochemical [12], and hydrothermal [13] methods, thermal (dry) technique (which is disproportionation, but commonly referred to as thermal reduction) is simple, chemical free, readily scaled-up, and avoids externally introducing heteroatom impurities [14-18]. One potentially attractive approach to graphene-based porous carbons is to cast GO suspensions into macroscopic bodies of desired shape, and allowing spontaneous sheet stacking to occur that essentially eliminates internal surface area, but then re-introduce porosity by partial exfoliation during thermal reduction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of exothermic thermal reduction / exfoliation of few-layer and porous rGO films.

This approach, however, requires that thermal reduction be carried out in a manner that preserves the physical form of the original cast object, which is a major challenge. The goal of the current study is to understand the GO partial exfoliation process sufficiently to achieve such shape-controlled, monolithic (single piece) carbon bodies with controlled porosity. The experimental parameters of GO thermal reduction are known to influence final product properties such as C:O ratio [14, 19, 20]. Exfoliation can also occur under some conditions when product gases (CO, CO2 and H2O) are generated rapidly within the lamellar structure [21] associated with heat generation, rapid reaction, and pressure build up that can overcome the van der Waals forces between individual sheets [20, 22-27], leading to partial or complete (re)-exfoliation. There are many parameters that affect thermal reduction and/or exfoliation: graphene oxide preparation method (Hummers, Brodie, Staudenmaier, Tour), C/O ratio (affected by preparation method), physical size and structure of the GO (cake vs film), applied vacuum, target temperature and externally applied instrument heating rate [11, 26-41]. High temperature heating and vacuum environments have been reported to be beneficial in producing rGO with high specific surface areas, by increasing the available energy and pressure difference for the driving force of decomposition of oxygen functionalities and interlayer separation [27, 28, 33, 38, 39]. Importantly, the local rate of sample heating, externally imposed by the heating instrument, is a key factor in determining rGO product surface area; generally, GO samples heated at rates above a threshold value will explosively disintegrate to rGO powder, yielding high porosity, but instead losing mechanical stability and the original GO morphology [34, 42]. Qiu et al. showed that the onset heating-rate value of this explosive-mode exfoliation for Hummers GO cake was at 10 K/min [28].

Mechanically and chemically stable free-standing rGO films are desirable for many applications that specifically benefit from the macroscopic dimensions, structure, and mechanical properties of a film. Flexible electrodes, passive samplers, biosensors and selective membranes require such a material which retains film structure [6-9, 43-47]. For instance, Castilho et al. suggested a novel use of GO films as breathable wearable barriers against mosquito bites [6]. Others proposed the use of graphene-based selective membranes for permeation or blockage of various environmental gases for personal protective equipment [7, 9]. To produce rGO films via thermal reduction, Legge et al. reported a method in which aqueous GO suspension was spray-coated onto a glass surface and then simultaneously chemically and thermally reduced to obtain an electrically conductive thin-film rGO coating [48]. Wei et al. [49] thermally reduced and exfoliated GO films by bringing a 200 soldering iron in contact with the film, and confirmed that there was an onset heating rate (10 ° C/min) for the explosive-mode, which was identical to the findings of thermally exfoliating GO cake by Qiu et al. [28]. X. Chen et al. [50] and C. Chen et al. [51] each demonstrated methods of heating a GO film confined between solid substrates (glass plates and silicon wafers, respectively) to achieve high electrical conductivities in free-standing rGO films.

Despite the progress, there is a lack of systematic studies of how various GO films (planar, textured, and confined) behave during the thermal exfoliation with varied instrument external heating rates and sample target temperatures. Only a few studies achieve porous materials by partial exfoliation with preservation of the original cast physical form. Herein, we (1) systematically explore the thermal exfoliation behavior of various GO films applying a range of target temperatures and instrument heating rates, and (2) demonstrate a simple method in which GO films are heated in confinement between borosilicate glass and stainless-steel plates to yield free-standing rGO films that are intact, porous, electrically conductive, and flexible.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Planar GO films with various thicknesses

Graphene oxide suspension was prepared by applying a modified Hummers’ method [52], in which graphite was pre-oxidized with K2S2O8 and P2O5 in concentrated H2SO4 and further oxidized with KMnO4 in concentrated H2SO4. This was followed by a vigorous two-step washing process with HCl and acetone. The product suspension concentration varied for each batch produced, ranging between 2.1 mg/mL and 4 mg/mL. The suspensions were stored in amber glass bottles or falcon tubes covered by aluminum foil to minimize graphene oxide exposure to light, given the tendency for aqueous graphene oxide suspensions to age when exposed to UV rays [53]. The concentration of the suspension was determined by a Jasco V-730 UV/Vis Spectrophotometer. The concentration was calculated applying Beer-Lambert law, with an experimentally determined calibration coefficient:

| (Eq. 1) |

Before processing graphene oxide suspensions into films, the suspension was placed into an ultrasonic bath for 10 minutes. The GO films were prepared similarly to our previous work, Qiu et al. [34], by pipetting certain volume of graphene oxide suspension onto a polystyrene substrate and leaving to dry in ambient conditions overnight. The GO film thickness could be increased to a target GO film thickness by additionally drop-casting fresh graphene oxide suspension to the previously dried layer. After reaching the desired thickness GO films were carefully peeled off from the polystyrene substrate to obtain planar free-standing GO films. The GO film thickness was calculated applying the following formula:

| (Eq. 2) |

with the bulk density of the GO taken to be 1.8 g/cm3 [54]. The number of nanosheet layers is estimated by dividing the thickness by the interlayer spacing, d = 0.8 nm, measured using X-ray diffraction crystallography (XRD).

2.1.2. Textured GO films

Textured GO films were synthesized by in-plane compression during relation of pre-stretched polystyrene substrates as described in Chen et al. [55], yielding 1D wrinkled and 2D crumpled films (Fig. S1). Briefly, polystyrene 3 cm by 1 cm substrates were pretreated with oxygen plasma in Harrick Plasma Cleaner PDC-001-HP. Graphene oxide suspension (3.55 mg/mL) was drop-cast on the plasma pretreated surface and completely dried in a laboratory oven set to 60° C. Then it was heated in a 140 ° C oven to allow the thermoplastic substrate to shrink. The substrate length was fixed from opposite ends leaving the two other ends unfixed. The uniaxial shrinkage during drying yielded 1D wrinkled films. The 2D crumpled films were generated similarly to 1D wrinkled films, except the ends of the substrate were not fixed. The substrate was removed by etching with dichloromethane.

2.2. GO thermal exfoliation

2.2.1. Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) thermal exfoliations

For unconfined thermal exfoliation, GO films were treated similarly to our previous work, Qiu et al. [34]. GO films were rolled into a 2mL aluminum oxide crucible and loaded into the TA Instruments Thermogravimetric Apparatus (TGA) (see Fig. S2). The TGA was used in its standard operation mode to supply heat for thermal exfoliation of GO in a high-purity nitrogen gas environment and at computer-controlled heating rates up to 100 K/min. The TGA was customized to perform thermal reduction/exfoliation at higher heating rates (up to 1600 K/min), accomplished by manually moving the quartz tube holding GO sample into the preheated 700 to 900 TGA furnace (see video in Fig. S3). A thermocouple at the sample location recorded the sample temperature over time, providing data for calculating the instrument applied heating rate.

2.2.2. Confined GO film thermal exfoliations

Planar GO films were confined between two microscope slides (75 × 22 × 2mm) held together by two binder clips (see Fig. S4). A Heratherm™ convectional laboratory oven was preheated to be at 250 target temperature, and the confined GO films at room temperature were placed in the preheated laboratory oven for heat up under an atmosphere of air. This set up is similar to one used in Chen et al. [50]. In order to improve the method and prepare rGO films with a larger lateral area we have prepared our own design for rGO films (see Fig. S5). The GO free-standing films were confined air-tightly between two square 3 mm thick borosilicate glass plates. The glass plates were further held together by stainless steel plates on each side and c-clamp screw compressors to apply pressure. The “sandwiched” GO sample at ambient temperature was placed quickly in the oven for thermal exfoliation, and the temperature of the sample was recorded by the attached thermocouple. The thermal time constant (time required to heat to steady state temperature) was about 10 minutes. The sample heating rate was at maximum 1200 K/min and averaged about 30 K/min.

2.3. GO and rGO characterization

The morphology and surface topography of GO and rGO films were investigated applying LEO 1530 VP ultra-high-resolution field emitter scanning electron microscope (SEM). Jasco FT/IR 4100 was used to investigate GO and rGO oxygen functional groups and to estimate the degree of GO thermal exfoliation to rGO. Bruker AXS D8 Advance XRD instrument with Cu K α radiation was used to investigate the atomic interlayer spacing, d, of GO and rGO films. Wavelength of λ = 1.5418Å was applied, and Bragg’s Law below was used to calculate the atomic interlayer spacing. A Thermo Fisher Scientific K-Alpha X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer (XPS) was used to obtain the XPS spectra’s – a plot of the number of electrons detected at a specific binding energy.

The Anton-Paar Autosorb-1 instrument was used to obtain N2 vapor isotherms at 77K and CO2 isotherms at 273K from which the surface areas based on the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory and pore size distributions (PSD) based on the non-local density functional theory (NLDFT) slit pore model were calculated [56, 57]. Electrical conductivities of samples were calculated by Eq. 3, following the methods of Valdes et al. [58], from the electrical resistance measurements taken with Lucas Labs S-302-4 Manual Four Point Resistivity Probing Equipment fitted with a SP4 Four Point Probe Head using a Keithley Model 2400 Series Source Meter as the DC power supply and multimeter (see Fig. S6). The use of a four-point probe, which consists of 4 equidistant (s = 1.0 mm) linearly aligned probes, removes effects of contact resistance and resistance from wires and probes, and can be used to take resistance measurements of a semi-infinite thin film of thickness t.

| (Eq. 3) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Planar free-standing GO films

Various thickness (9 to 36-μm) free-standing planar GO films are shown in Fig. 2a. The SEM image of a 2-μm thick GO film is shown in Fig. 2b and 2c.

Fig. 2.

a) Optical images of GO films with varying thicknesses. 2b) and 2c) SEM images of a 1-cycle planar free-standing GO film. Film thickness is approximately 2-μm.

The external surface area of all GO films shown in Fig. 2a was approximately 21 cm2. In this study, the free-standing GO films thicknesses were varied from 2-μm up to 50-μm. The digital images in Fig. 2a show some imperfections in film surface as GO film thickens. This is likely due to the presence of local air-pockets in the film as the cycle number (each new drop-cast batch added) grew. The SEM images (Fig. 2b and 2c) of 1 drop-cast freestanding GO film with approximately 2-μm thickness suggested that the individual layers of graphene oxide are packed tightly together without any openings. The N2 probe surface area measurements for of all free-standing GO films were unsuccessful, meaning that the surface area with such a low GO film mass was undetectable. However, we were able to measure a 36-μm thick GO film CO2 BET area to be 38 m2/g. This is still a fairly small surface area, and likely originates from above-mentioned air pocket formation between repeated drop-casted layers to achieve this thickness.

3.2. “Low” instrument-set heating rate rGO films

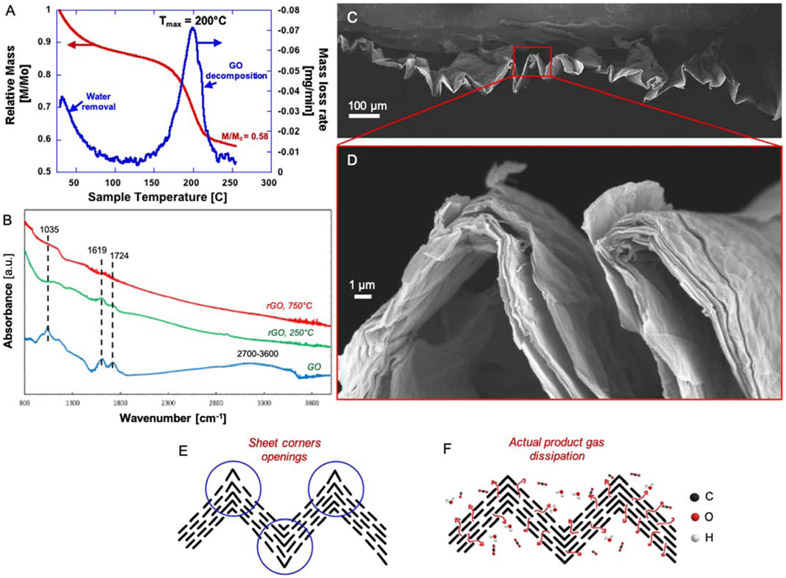

The degree of exfoliation is known to be strongly affected by heating rate [21, 28, 33, 34, 38]. Our earlier studies [28, 34] showed that explosive exfoliation of GO cake took place when the instrument-set heating rate was 10 K/min or above. Therefore, the “low” heating rate designation was given to the experiments during which the GO exfoliation occurred without GO explosion (any heating rate ≤ 10 K/min), and “high” heating rate designation to the exfoliation process at which GO decomposed explosively (any heating rate >10 K/min). A typical TGA thermogram of thermal exfoliation of a GO film at “low” instrument-set heating rate is shown in Fig. 3a. In this instance, the GO film was exfoliated at 10 K/min instrument heating rate and target temperature of 250°C and did not result an explosive GO runaway reaction.

Fig. 3.

a) Planar GO film thermal exfoliation in the TGA at 10 K/min heating rate. Exfoliation reaction occurs without an explosive thermal runaway reaction. 3b) A 3-μm thick GO and 3c) a 9-μm thick GO film XRD spectra comparatively with their rGO film XRD spectra. Note, GO atomic interlayer spacing is approximately 0.85-nm, and rGO interlayer spacing approximately 0.36-nm. 3d) – 3f) Low and high magnification SEM images of rGO films exfoliated at 10 K/min in TGA.

The GO film runaway reaction begins at around 150 ° C and the reaction rate reaches a maximum at 211 ° C, which is similar to results for graphite oxide cake samples. The relative mass at the end of the decomposition is 0.52, indicating that almost half its original mass is lost due to the release of the product gases such as CO2, CO and H2O [27]. The XRD spectra of two GO and rGO films with varying thicknesses are shown in Fig. 3b and 3c. The average GO interlayer spacing (d) is about 0.85 nm, which is consistent with the results reported in literature [59, 60]. With calculated GO film thickness (Eq. 2) and measured GO interlayer spacing (d ~ 0.85 nm), one can approximately calculate the number of individual graphene oxide layers in the GO film. For example, a 9-μm thick GO film with 0.85-nm atomic interlayer distance would have approximately 10,600 individual graphene oxide layers.

The XRD spectra of rGO are comparatively shown with the GO spectra in Fig. 3b and 3c. The rGO interlayer spacing is independent of rGO film thickness and is approximately 0.367 nm, which is close to a typical graphenic carbon interlayer spacing of 0.34 nm [61, 62]. This effect is attributed to the removal of water and oxygen functionalities located between each individual graphene oxide layer, causing the collapse of the GO structure to a graphenic structure. The rGO films had an electrical conductivity of ~400 S/m, which is much higher than GO films (< 10 S/m). The SEM results in Fig. 3d to 3f support these findings. The SEM images show minimal interlayer separation, except some of the openings at the edges of the rGO film. The N2 BET specific surface area measurements were also consistent in this way; rGO film surface areas were mostly undetectable or fairly low. The rGO film surface area measured with N2 probe was 0.85 m2/g and with the CO2 probe 40 m2/g suggesting that the rGO films were essentially nonporous. These results aligning closely with the Qiu et al. study [28], in which rGO cake exfoliated at ‘low’ instrument-set heating rate was reported to be essentially non-porous. The GO film surface chemistry changes during thermal exfoliation at 250°C and 750°C target temperatures are shown in Fig. 4a and 4b.

Fig. 4.

a) The FTIR spectra of planar GO and rGO films. The GO films were exfoliated at 250°C and 750°C at 10 K/min instrument heating rate in the TGA. 4b) The XPS spectra of the same GO and rGO films. The C/O atomic ratios show the partial exfoliation of planar GO films.

The FTIR analysis of GO film shows that most of the oxygen functionalities are removed when heated to 250°C. The large hydroxyl group (COOH, C-OH) peak at 2900-3600 cm−1 is eliminated completely. Most of the epoxides and ethers at ~932 cm−1 and ~1035 cm−1 are also removed from GO film exfoliated at 250°C. It seems there are some carboxyl groups or ketones (C=O, 1724 cm−1) that are unremoved at 250°C. The FTIR spectra for the GO film heated to 750 shows that almost all oxygen functionalities are removed. The XPS results shown in Fig. 4b closely align with the FTIR results. The rGO film C/O atomic ratio reaches to a maximum of 6.8 if exfoliated at 750°C.

Herein, we report a threshold GO film thickness (36-μm) at which the GO films behave slightly differently when exfoliated at instrument-set ‘low’ heating rate of 10 K/min. The results are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

a) and 5b) The low and high magnification SEM images of rGO film originating from 36-μm thick GO film. The GO film layers are visibly opened up (partial exfoliation). 5c) The NLDFT Pore Size Distribution (PSD) from the N2 adsorption isotherm of the same rGO film sample shown in 5a and 5b. 5d) Hypothetical models of how <36-μm and >36-μm GO films thermally exfoliate at “low” instrument-set heating rate = 10 K/min. For thickness t1 the product gases leave perpendicular to the film surface leaving behind low or no porosity. At the threshold, 36-μm GO film thickness (t2 on diagram) the product gas pressures increase locally in the film interior to values high enough for the rapid expansion of the GO film system and creating an N2 BET specific surface area (SSA) of 171 m2/g. In this scenario, we could likely reflect that significant amounts of gas escape through transport routes parallel to the GO layers.

By evaluating these SEM images (Fig. 5a and 5b), one could notice that the film integrity is nearly lost. The edges of the film show clear signs of partial exfoliation. The large gaps between opened layers seem to be the product gas pathways during thermal exfoliation. The specific surface areas measured with the N2 and CO2 probes were 171 m2/g and 1471 m2/g, respectively. Pore size distribution (shown in Fig. 5c) were obtained from the same rGO N2 adsorption isotherm recorded at 77K. The pores seen by the N2 probe are the mesopores with sizes 2.9 nm, 5.4 nm, and 7.6 nm. The micropores (pore size < 2.0 nm), were not detected. Conceptual models of the partial exfoliation mechanism are shown in Fig. 5d. For thin GO films (<36-μm; t1 on the diagram), the product gas path perpendicular to the film (z-direction) is the minimum resistance path. These z-directional pathways are rather short relative to the path parallel to the GO layers, resulting in rGO film with low specific surface area and porosity. As GO film thickness increases, the z-directional path resistance increases. At certain critical GO film thickness (36-μm and above), local pockets of high-pressure product gas are formed during thermal exfoliation between the layers (due to sufficient resistance in the z-directional pathways). These pockets of high-pressure product gases overcome van der Waals forces to expand layers and the product gases can also escape parallel to the film (x, y-direction), leaving behind longer pathways. A greater degree of local partial exfoliation is achieved, yielding a higher rGO film surface area and porosity.

3.3. “High” instrument-set heating rate rGO films

The “high” instrument-set heating rate designation were given to the heating rates that resulted in explosive thermal exfoliation of GO films to a rGO powder. Table 1 summarizes the results of the rGO powder surface area and porosity for various GO film thicknesses and instrument-set heating rates.

Table 1.

The N2 BET surface areas and total pore volumes of rGO powder obtained from planar GO films with various thicknesses. At any instrument heating rate >100 K/min, GO films with thicknesses from 3 to 45-μm exfoliated explosively with the destruction of the film geometry.

| GO Film Thickness (μm) |

Instrument-set Heating Rate (K/min) |

N2 BET, Specific Surface Area (m2/g) |

Total Pore Volume (cc/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 560 | 757 | 1.75 |

| 9 | 550 | 714 | 1.88 |

| 27 | 412 | 689 | 1.51 |

| 45 | 105 | 782 | 1.57 |

GO films at any thickness tested exfoliated explosively at instrument-set heating rates of 100 K/min and above, yielding a fluffy low-density rGO powder product (Fig. 6a-c). As the SEM images of the rGO powder suggest the grain sizes are irregular, ranging from sub-micron up to 100-μm. Some of the rGO particles exhibit “accordion-like” structure (GO partial exfoliation), which has been seen in our previous work with explosively exfoliated rGO [28]. A N2 adsorption isotherm of a rGO powder sample is shown in Fig. 6d, with the corresponding pore size distribution (PSD) in Fig 6e. The source material was a 27-μm thick GO film before it explosively was exfoliated at 412 K/min, resulting a rGO powder with 689 m2/g specific surface area and 1.5 cc/g total pore volume. The pore size distribution shows micro-porosity and mostly lower-end size mesoporosity (2 to 20 nm). Both the isotherm and PSD have patterns commonly seen for rGO materials (note the periodicity in PSD) [10]. The specific surface areas of rGO powders fell in a narrow range from 700 to 800 m2/g. The specific surface area was independent of GO film thickness and instrument-set heating rate (> 100 K/min). This is an interesting finding, suggesting a probable existence of a threshold thickness (much thinner than 3-μm) from which higher thickness GO film all explosively exfoliate at high instrument-set heating rates (Table 1). We have not investigated this threshold thickness. Moreover, the results in Table 1 also suggest that the instrument-set heating rate (between 105 and 560 K/min) has little or no effect to the rGO powder surface area and porosity. At high heating rates, the GO self-heating reaction surpasses the instrument external heating rate and GO exfoliates at the same degree no matter what the instrument heating rate is. This is very similar result reported by Qiu et al. [28] for GO cakes, except that for the threshold heat rate value for rGO films when the explosive thermal exfoliation begins is 100 K/min, rather than 10 K/min. In terms of obtaining materials with high surface area and porosity, these rGO powders would clearly be a success material.

Fig. 6.

a) Optical image of fluffy low-density rGO powder obtained after explosive thermal exfoliation of GO film. 6b) and 6c) the SEM images of the same powder at different magnifications. 6d) N2 adsorption isotherm of rGO powder obtained after explosively exfoliating a 27-μm thick GO film with 412 K/min instrument-set heating rate in TGA. 6e) Pore size distribution obtained from N2 adsorption isotherm data 6d) applying NLDFT slit pore model. Most pores present in rGO powder are small size mesopores ranging from 2.8 nm to 20 nm. The porosity in rGO powders originates from the expanded irregular stacking of individual rGO platelets as a result of partial exfoliation.

We have undertaken a series of experiments with GO films and have determined the instrument-set heating rate and target temperature threshold values at which exfoliation proceeds explosively. The results are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

The 2D regime diagram for thermal exfoliation of graphene oxide films showing four quadrants that give rise to different morphologies and physical properties. Starting materials are free-standing planar GO films, and the regimes are determined by threshold target temperature and instrument-set heating rates.

This diagram divides the products into three categories with easily identifiable characteristics, depending on the instrument heating rate and target temperatures. All three categories materials – GO films (labeled blue), rGO powders (black), and rGO films (yellow) – have characteristics that are useful for different applications, depending on the application’s need for high specific surface area, mechanical strength, or electrical conductivity. As seen, the explosive GO film exfoliation takes place in the experiments at which the instrument-set heating rates were 100 K/min and above. This threshold value is 10x higher than that reported in our ealier work with bulk graphite oxide cake. This finding is not completely unexpected, since GO films have a much greater surface to volume ratio compared to GO cakes. Thin films with this larger outer surface area allow greater heat loss, while a cake particle has no superthin dimension. The film higher surface area to volume ratio delays internal heat build-up during thermal exfoliation, causing the heating rate threshold value for the explosive exfoliation to be higher for films.

3.4. Effect of film texture on reduction and partial exfoliation behavior.

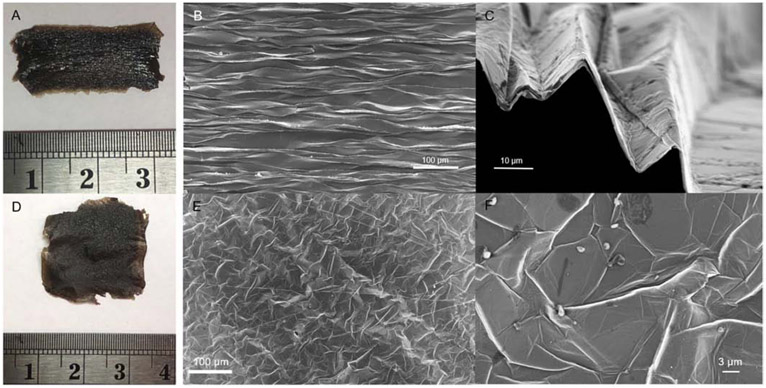

There is a great interest in texturing graphene films to impart stretchability [63-65] or other functions such as modified hydrophilicity and electrochemical responsivity [55, 64, 66, 67]. It is unknown if or how these microscale features will affect thermal exfoliation, gas release, and developed porosity. 1D wrinkled and 2D crumpled GO films were therefore prepared as shown in Fig. S1. The optical images of the GO films are shown in Fig. 8a and 8d. The SEM images of 1D wrinkled and 2D crumpled 1-μm thick films are shown in Fig. 8b, 8c, 8e and 8f.

Fig. 8.

a) An optical image of 1-μm thick 1D wrinkled GO film. 8b) and 8c) SEM images of 1D wrinkled 1-μm thick GO film. Note, there is nearly perfect unidirectional 1D wrinkling topography. Wrinkles have a characteristic “wavelength” of 15 to 20-μm. 8d) An optical image of 1-μm thick 2D crumpled GO film. 8e) and 8f) The SEM images of 2D crumpled 1-μm thick GO film.

The wrinkled topography introduces corners or “kinks” that initially were thought to increase the availability of product gas pathways parallel to the film during thermal exfoliation (Fig. 8c and 8e). The product gases would potentially escape through these corner channels instead of the minimum energy path (perpendicular to film). Both wrinkled and crumpled GO films were thermally exfoliated in the TGA in 10 K/min in N2 flow. The wrinkled rGO film characterization results are cumulatively shown in Fig. 9 panel. The partially reduced textured films (see Fig. 9c and 9d SEM images) show some degree of flexibility. However, the investigation of thermally reduced textured film stretchability was not the aim of this study. Chen et al. [65] show that textured rGO films can be uniaxially stretched up to 35% without compromising the rGO film integrity. Overall, the higher the reduction extent the harder it is to stretch the films back without their destruction [65]. The thermogram shown in Fig. 9a is nearly identical to the planar GO film thermal exfoliation thermogram shown on Fig. 3a. This was not a surprise, since the same modified Hummers GO suspension used to prepare wrinkled and crumpled GO films. In addition, the FTIR spectra of wrinkled rGO films suggested that most of the oxygen functionalities were lost at 250°C (similar to planar rGOs, see Fig. 4a). The low and high magnification SEM images in Fig. 9c and 9d show little to no interlayer separation or pore development in the channels as desired. The BET specific surface area of the rGO was measured to be 0.7 m2/g, which is very similar to the surface area obtained for planar rGO films when exfoliated at ‘low’ instrument-set heating rate and target temperature. Fig. 9e and 9f show a conceptual model of product gas release through interlayer spaces (least resistance path), which is very similar to exfoliation paths seen in thermal exfoliation of drop-cast GO films (Fig. 5d). Although this technique does not create surface area by partial exfoliation, it provides a simple route to microtextured flexible and stretchable films in the rGO conductive platform.

Fig. 9.

a) Thermal exfoliation of 1D wrinkled 1-μm thick GO film in the TGA at 10 K/min. Note, exfoliation occurs without explosion. 9b) The FTIR spectra of 1-μm thick 1D wrinkled GO and rGO films. The GO films were exfoliated at 250°C and 750°C at 10 K/min instrument heating rate in TGA, 9c) and 9d) SEM images of 1D wrinkled thermally exfoliated up to 250°C at the low heating rate at 10 K/min. 9e) and 9f) Conceptual models how 1D wrinkled GO films thermally exfoliate. Product gases leave perpendicular to the film surface leaving behind low or no porosity rGO films.

We have also explored GO wrinkled films with “high” instrument-set heating rates. When an instrument-set heating rate of 770 K/min was applied, the 1-μm wrinkled GO film exfoliated similarly to planar films, exfoliating explosively into fine fluffy rGO powder with fairly high specific surface area (445 m2/g) N2 BET. The surface area and porosity results are shown in Fig. 10. The rGO powder pore size distribution suggests periodicity, which has been seen with many rGO powders (see Fig. 6e and Guo et al. [10] Fig. 1b.).

Fig. 10.

a) The N2 adsorption isotherm of rGO powder obtained after 1-μm 1D wrinkled film thermal exfoliation at 770 K/min. 10b) The rGO powder NLDFT slit pore model pore size distribution obtained from N2 isotherm 10a).

The results with wrinkled and crumpled GO films suggest that introduction of microscale texturing does not alter the fundamentals of thermal reduction behavior.

3.5. Use of confinement to make intact porous films

The experiments described above yield a variety of useful carbon materials with different physical forms, surface areas, electrical conductivities, and surface textures, but do not identify any method for introducing high surface area to cast GO films while preserving their macroscopic film structure. We therefore explored spatial confinement to inhibit film destruction and potentially enhance the degree of partial exfoliation by increasing internal gas pressures. We confined the planar GO films between two borosilicate glass microscope slides (75 mm × 22mm × 2mm) and held the glass-GO assembly together with clips (Fig. S4), similar to Chen et al. [50]. Borosilicate glass is nonporous, and has favorable thermal properties that include a high softening point (~500°C) and low coefficient of linear thermal expansion (~3.3×10−6 /K) [68]. The sandwiched GO film was heated to 250°C-target temperature for 30 or 60 minutes. The heating rate and estimated convectional heat transfer coefficient of the microslide-GO assembly gave a Biot number of 0.084, which is low enough to be treated as a thermally ‘thin body,’ implying essentially constant internal temperature during fast assembly heat up process. The resulting rGO films are intact, stable to handling in free-standing form and have mechanical flexibility (Fig. 11a-c).

Fig. 11.

The rGO films obtained by thermal treatment of planar GO films confined in between borosilicate glass slides. 11a) Optical image of rGO film obtained from a 4.2-μm drop-cast 6-cycle GO film. 11b) The optical image of rGO film obtained from a 6.2-μm thick 2-cycle planar GO film 11c) The optical image of rGO film obtained from a 3.4-μm thick drop-cast 1-cycle GO film 11d) The FTIR spectra of rGO films exfoliated for 30-min and 60-min at 250°C. The rGO film degree of exfoliation is close to identical.

The film surfaces (Fig. 11a, b) possess rough or crumpled surface textures, which are potentially due to air pockets while building the GO film thickness in cyclic manner. The 1-cycle GO film when exfoliated between borosilicate microslides produces shiny non-crumpled surface texture and highly flexible rGO film. The FTIR analysis of thermally exfoliated rGO films (Fig. 11d) suggests that the removal of oxygen functional groups reached completion in 30 minutes at the target exfoliation temperature of 250°C. There are no significant differences between the rGO film spectra obtained after 30 minutes and that of 60 minutes, which suggest that the thermal exfoliation reaction is complete within 30 minutes. These results are also consistent with the FTIR results shown prior in Fig. 4a and Fig. 9b. The electrical conductivity of these rGO films were measured to be in the range of 601 to 690 S/m, which suggests successful partial exfoliation without major graphene plane defects. In order to make precise quantitative surface area measurements, we have fabricated larger films using a modified technique to allow the exfoliation of larger GO films.

Fig. S5A shows the scaled-up design that incorporates two stainless steel plates to confine the GO film during the thermal exfoliation. The experiment protocol was identical with the microslide-GO assembly heat up protocol – 250°C target temperature for 30-minutes. The planar precursor GO films and resulting rGO films are shown in Fig. 12 panel.

Fig. 12.

a) The optical image of drop-cast GO film used in thermal exfoliation experiment. 12b) The optical image of a rGO film obtained from a confined 6.2-μm thick drop-cast 9-cycle GO film, 12c) The optical image of rGO film obtained from a confined 19.6-μm thick drop-cast 3-cycle GO film, 12d) The optical image of rGO film obtained from a confined 3.2-μm thick drop-cast 6-cycle GO film. 12e) The GO and confined rGO film FTIR spectra. The confined GO film was thermally exfoliated at 250°C, 12f) The XPS spectra of the same GO and confined rGO films. The C/O atomic ratios show the partial exfoliation of confined GO film. Although FTIR spectra show that most of the O-functionalities are lost, the XPS spectra confirm that partial thermal exfoliation has taken place.

The rGO films maintained their film structure, mechanical stability and flexibility. Multi cycle drop-casting produced air-pockets between cycles and was observed as visible defects or rough surface texture. BET area using CO2 as an adsorbate were 581 to 971 m2/g, while the N2 areas were undetectable, indicating the presence of super-micropores (< 1nm). The electrical conductivity of these rGO films were measured to be 757 S/m to 950 S/m. Therefore, we have shown that intact microporous rGO films with mechanical stability and high electrical conductivity can be produced with this straightforward simple method. These rGO films can be prepared to be more flexible and less brittle as needed by varying film thickness (see Fig. 11a vs. Fig. 11c). As shown in this work, the confinement technique appears to be scalable, which is important for creating large area rGO films for some applications (see Fig. 12).

4. Conclusions

This work shows how partial thermal exfoliation of graphene oxide (GO) multilayer nanosheet films can be used to control pore structure and electrical conductivity of planar and confined GO films. GO films are shown to exfoliate explosively when the instrument-set heating rates are 100 K/min and above leading to surface areas ~700 m2/g, but with complete destruction of the film geometry. At low heating rates, GO films with thickness < 36 μm yield mechanically stable rGO films with high electrical conductivity (~400 S/m), but undetectable surface area and porosity. In contrast, thicker films (> 36 μm) exfoliate destructively into rGO film fragments and with a N2 BET surface area of 171 m2/g. Textured films with engineered micro-wrinkling and crumpling do not alter the extent of thermal exfoliation if compared to planar films. The product gases are escaping the rGO film perpendicular to the film surface – the least resistant path. Sandwiching GO precursor films between borosilicate glass and stainless-steel plates during partial exfoliation at 250°C produces material with 757 S/m conductivity and 500 – 970 m2/g CO2 surface area in the form of a flexible film that preserves the macroscopic structure of the original cast body. These results are useful for researchers trying to optimize thermal treatment process to produce a variety of rGO films for a diverse set of applications such as solar cells, flexible electrodes, and sensors.

Supplementary Material

Partial thermal exfoliation allows control of rGO film pore structure and electrical conductivity.

Textured films with engineered micro-wrinkling and crumpling show similar thermal exfoliation behavior to planar films.

Planar and textured GO films exfoliate explosively when instrument-set heating rates are 100 K/min and above.

Precursor film confinement prior to thermal exfoliation allows to produce high electrical conductivity and porosity rGO films.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible thanks to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program (Grant P42 ES013660) and the Brown University School of Engineering. Senior Technical Assistant Benjamin Lyons is acknowledged for the technical assistance while preparing plates for film confinement experiments.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Bonaccorso F, Colombo L, Yu G, Stoller M, Tozzini V, Ferrari AC, Ruoff RS, Pellegrini V, Graphene, related two-dimensional crystals, and hybrid systems for energy conversion and storage, Science 347(6217) (2015) 1246501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Edwards RS, Coleman KS, Graphene synthesis: relationship to applications, Nanoscale 5(1) (2013) 38–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Torrisi F, Coleman JN, Electrifying inks with 2D materials, Nature Nanotechnology 9(10) (2014) 738–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Liu J, Charging graphene for energy, Nature Nanotechnology 9(10) (2014) 739–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lee GH, Lee JW, Choi JI, Kim SJ, Kim YH, Kang JK, Ultrafast Discharge/Charge Rate and Robust Cycle Life for High-Performance Energy Storage Using Ultrafine Nanocrystals on the Binder-Free Porous Graphene Foam, Advanced Functional Materials 26(28) (2016) 5139–5148. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Castilho CJ, Li D, Liu M, Liu Y, Gao H, Hurt RH, Mosquito bite prevention through graphene barrier layers, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(37) (2019) 18304–18309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Steinberg R, Cruz M, Mahfouz N, Qiu Y, Hurt R, Breathable Vapor Toxicant Barriers Based on Multilayer Graphene Oxide, ACS Nano 11(6) (2017) 5670–5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nair RR, Wu HA, Jayaram PN, Grigorieva IV, Geim AK, Unimpeded Permeation of Water Through Helium-Leak-Tight Graphene-Based Membranes, Science 335(6067) (2012) 442–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Guo F, Silverberg G, Bowers S, Kim S-P, Datta D, Shenoy V, Hurt RH, Graphene-Based Environmental Barriers, Environmental Science & Technology 46(14) (2012) 7717–7724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Guo F, Creighton M, Chen YT, Hurt R, Kulaots I, Porous structures in stacked, crumpled and pillared graphene-based 3D materials, Carbon 66 (2014) 476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Stankovich S, Dikin DA, Piner RD, Kohlhaas KA, Kleinhammes A, Jia Y, Wu Y, Nguyen ST, Ruoff RS, Synthesis of graphene-based nanosheets via chemical reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide, Carbon 45(7) (2007) 1558–1565. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shao YY, Wang J, Engelhard M, Wang CM, Lin YH, Facile and controllable electrochemical reduction of graphene oxide and its applications, Journal of Materials Chemistry 20(4) (2010) 743–748. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhou Y, Bao QL, Tang LAL, Zhong YL, Loh KP, Hydrothermal Dehydration for the "Green" Reduction of Exfoliated Graphene Oxide to Graphene and Demonstration of Tunable Optical Limiting Properties, Chemistry of Materials 21(13) (2009) 2950–2956. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pei SF, Cheng HM, The reduction of graphene oxide, Carbon 50(9) (2012) 3210–3228. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shams SS, Zhang R, Zhu J, Graphene synthesis: a Review, Materials Science-Poland 33(3) (2015) 566–578. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Singh RK, Kumar R, Singh DP, Graphene oxide: strategies for synthesis, reduction and frontier applications, Rsc Advances 6(69) (2016) 64993–65011. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhu YW, Murali S, Cai WW, Li XS, Suk JW, Potts JR, Ruoff RS, Graphene and Graphene Oxide: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications, Advanced Materials 22(35) (2010) 3906–3924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhu YW, Stoller MD, Cai WW, Velamakanni A, Piner RD, Chen D, Ruoff RS, Exfoliation of Graphite Oxide in Propylene Carbonate and Thermal Reduction of the Resulting Graphene Oxide Platelets, ACS Nano 4(2) (2010) 1227–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Acik M, Chabal Y, A review on thermal exfoliation of graphene oxide, Journal of Materials Science Research 2(1) (2013) 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Acik M, Lee G, Mattevi C, Pirkle A, Wallace RM, Chhowalla M, Cho K, Chabal Y, The Role of Oxygen during Thermal Reduction of Graphene Oxide Studied by Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy, Journal of Physical Chemistry C 115(40) (2011) 19761–19781. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Qiu Y, Collin F, Hurt RH, Kulaots I, Thermochemistry and kinetics of graphite oxide exothermic decomposition for safety in large-scale storage and processing, Carbon 96 (2016) 20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schafhaeutl C, Ueber die Verbindungen des Kohlenstoffes mit Silicium, Eisen und anderen Metallen, welche die verschiedenen Gallungen von Roheisen, Stahl und Schmiedeeisen bilden, Journal für Praktische Chemie 21(1) (1840) 129–157. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brodie BC, On the atomic weight of graphite, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 149 (1859) 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boehm HP, Stumpp E, Citation errors concerning the first report on exfoliated graphite, Carbon 45(7) (2007)1381–1383. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dreyer DR, Ruoff RS, Bielawski CW, From Conception to Realization: An Historial Account of Graphene and Some Perspectives for Its Future, Angewandte Chemie-International Edition 49(49) (2010) 9336–9344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang C, Lv W, Xie XY, Tang DM, Liu C, Yang QH, Towards low temperature thermal exfoliation of graphite oxide for graphene production, Carbon 62 (2013) 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Schniepp HC, Li JL, McAllister MJ, Sai H, Herrera-Alonso M, Adamson DH, Prud'homme RK, Car R, Saville DA, Aksay IA, Functionalized single graphene sheets derived from splitting graphite oxide, Journal of Physical Chemistry B 110(17) (2006) 8535–8539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Qiu Y, Moore S, Hurt R, Külaots I, Influence of external heating rate on the structure and porosity of thermally exfoliated graphite oxide, Carbon 111 (2017) 651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Botas C, Alvarez P, Blanco P, Granda M, Blanco C, Santamaria R, Romasanta LJ, Verdejo R, Lopez-Manchado MA, Menendez R, Graphene materials with different structures prepared from the same graphite by the Hummers and Brodie methods, Carbon 65 (2013) 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Jankovský O, Marvan P, Nováček M, Luxa J, Mazánek V, Klímová K, Sedmidubský D, Sofer Z, Synthesis procedure and type of graphite oxide strongly influence resulting graphene properties, Applied Materials Today 4 (2016) 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- [31].You S, Luzan SM, Szabó T, Talyzin AV, Effect of synthesis method on solvation and exfoliation of graphite oxide, Carbon 52 (2013) 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Boehm H, Clauss A, Fischer G, Hofmann U, Surface properties of extremely thin graphite lamellae, Proceedings of the fifth Conference on Carbon, Pergamon Press, 1962, pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- [33].McAllister MJ, Li JL, Adamson DH, Schniepp HC, Abdala AA, Liu J, Herrera-Alonso M, Milius DL, Car R, Prud'homme RK, Aksay IA, Single sheet functionalized graphene by oxidation and thermal expansion of graphite, Chemistry of Materials 19(18) (2007) 4396–4404. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Qiu Y, Guo F, Hurt R, Kulaots I, Explosive thermal reduction of graphene oxide-based materials: Mechanism and safety implications, Carbon 72 (2014) 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Li SM, Yang SY, Wang YS, Tsai HP, Tien HW, Hsiao ST, Liao WH, Chang CL, Ma CCM, Hu CC, N-doped structures and surface functional groups of reduced graphene oxide and their effect on the electrochemical performance of supercapacitor with organic electrolyte, Journal of Power Sources 278 (2015) 218–229. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li SM, Yang SY, Wang YS, Lien CH, Tien HW, Hsiao ST, Liao WH, Tsai HP, Chang CL, Ma CCM, Hu CC, Controllable synthesis of nitrogen-doped graphene and its effect on the simultaneous electrochemical determination of ascorbic acid, dopamine, and uric acid, Carbon 59 (2013) 418–429. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wu ZS, Ren WC, Gao LB, Liu BL, Jiang CB, Cheng HM, Synthesis of high-quality graphene with a pre-determined number of layers, Carbon 47(2) (2009) 493–499. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhang HB, Wang JW, Yan Q, Zheng WG, Chen C, Yu ZZ, Vacuum-assisted synthesis of graphene from thermal exfoliation and reduction of graphite oxide, Journal of Materials Chemistry 21(14) (2011) 5392–5397. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lv W, Tang DM, He YB, You CH, Shi ZQ, Chen XC, Chen CM, Hou PX, Liu C, Yang QH, Low-Temperature Exfoliated Graphenes: Vacuum-Promoted Exfoliation and Electrochemical Energy Storage, ACS Nano 3(11) (2009) 3730–3736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Vivekchand SRC, Rout CS, Subrahmanyam KS, Govindaraj A, Rao CNR, Graphene-based electrochemical supercapacitors, Journal of Chemical Sciences 120(1) (2008) 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Du XA, Guo P, Song HH, Chen XH, Graphene nanosheets as electrode material for electric double-layer capacitors, Electrochimica Acta 55(16) (2010) 4812–4819. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yang SJ, Kim T, Jung H, Park CR, The effect of heating rate on porosity production during the low temperature reduction of graphite oxide, Carbon 53 (2013) 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Yin Z, Sun S, Salim T, Wu S, Huang X, He Q, Lam YM, Zhang H, Organic Photovoltaic Devices Using Highly Flexible Reduced Graphene Oxide Films as Transparent Electrodes, ACS Nano 4(9) (2010) 5263–5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kang D, Kwon JY, Cho H, Sim J-H, Hwang HS, Kim CS, Kim YJ, Ruoff RS, Shin HS, Oxidation Resistance of Iron and Copper Foils Coated with Reduced Graphene Oxide Multilayers, ACS Nano 6(9) (2012) 7763–7769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].David L, Singh G, Reduced Graphene Oxide Paper Electrode: Opposing Effect of Thermal Annealing on Li and Na Cyclability, Journal of Physical Chemistry C 118(49) (2014) 28401–28408. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Song N-J, Chen C-M, Lu C, Liu Z, Kong Q-Q, Cai R, Thermally reduced graphene oxide films as flexible lateral heat spreaders, Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2(39) (2014) 16563–16568. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Su Y, Kravets VG, Wong SL, Waters J, Geim AK, Nair RR, Impermeable barrier films and protective coatings based on reduced graphene oxide, Nature Communications 5(1) (2014) 4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Legge EJ, Ahmad M, Smith CTG, Brennan B, Mills CA, Stolojan V, Pollard AJ, Silva SRP, Physicochemical characterisation of reduced graphene oxide for conductive thin films, Rsc Advances 8(65) (2018) 37540–37549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wei W, Guan T, Li C, Shen L, Bao N, Heating Rate-Controlled Thermal Exfoliation for Foldable Graphene Sponge, Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 59(7) (2020) 2946–2952. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chen X, Meng D, Wang B, Li B-W, Li W, Bielawski CW, Ruoff RS, Rapid thermal decomposition of confined graphene oxide films in air, Carbon 101 (2016) 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chen C-M, Huang J-Q, Zhang Q, Gong W-Z, Yang Q-H, Wang M-Z, Yang Y-G, Annealing a graphene oxide film to produce a free standing high conductive graphene film, Carbon 50(2) (2012) 659–667. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Hummers WS, Offeman RE, Preparation of Graphitic Oxide, Journal of the American Chemical Society 80(6) (1958) 1339–1339. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Guardia L, Villar-Rodil S, Paredes JI, Rozada R, Martínez-Alonso A, Tascón JMD, UV light exposure of aqueous graphene oxide suspensions to promote their direct reduction, formation of graphene–metal nanoparticle hybrids and dye degradation, Carbon 50(3) (2012) 1014–1024. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dikin DA, Stankovich S, Zimney EJ, Piner RD, Dommett GHB, Evmenenko G, Nguyen ST, Ruoff RS, Preparation and characterization of graphene oxide paper, Nature 448(7152) (2007) 457–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Chen P-Y, Sodhi J, Qiu Y, Valentin TM, Steinberg RS, Wang Z, Hurt RH, Wong IY, Multiscale Graphene Topographies Programmed by Sequential Mechanical Deformation, Advanced Materials 28(18) (2016) 3564–3571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lastoskie C, Gubbins KE, Quirke N, Pore-Size Heterogeneity and the Carbon Slit Pore - a Density-Functional Theory Model, Langmuir 9(10) (1993) 2693–2702. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ravikovitch PI, Vishnyakov A, Russo R, Neimark AV, Unified Approach to Pore Size Characterization of Microporous Carbonaceous Materials from N2, Ar, and CO2 Adsorption Isotherms, Langmuir 16(5) (2000) 2311–2320. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Valdes L, Resistivity Measurements on Germanium for Transistors, Proceedings of the IRE 42(2) (1954) 420–427. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lian B, Deng J, Leslie G, Bustamante H, Sahajwalla V, Nishina Y, Joshi RK, Surfactant modified graphene oxide laminates for filtration, Carbon 116 (2017) 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Joshi RK, Carbone P, Wang FC, Kravets VG, Su Y, Grigorieva IV, Wu HA, Geim AK, Nair RR, Precise and Ultrafast Molecular Sieving Through Graphene Oxide Membranes, Science 343(6172) (2014) 752–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bacon GE, The interlayer spacing of graphite, Acta Crystallographica 4(6) (1951) 558–561. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Çakmak G, Öztürk T, Continuous synthesis of graphite with tunable interlayer distance, Diamond and Related Materials 96 (2019) 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zang J, Cao C, Feng Y, Liu J, Zhao X, Stretchable and High-Performance Supercapacitors with Crumpled Graphene Papers, Scientific Reports 4(1) (2015) 6492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Hong J-Y, Kim W, Choi D, Kong J, Park HS, Omnidirectionally Stretchable and Transparent Graphene Electrodes, ACS Nano 10(10) (2016) 9446–9455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Chen P-Y, Zhang M, Liu M, Wong IY, Hurt RH, Ultrastretchable Graphene-Based Molecular Barriers for Chemical Protection, Detection, and Actuation, ACS Nano 12(1) (2017) 234–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Zang J, Ryu S, Pugno N, Wang Q, Tu Q, Buehler MJ, Zhao X, Multifunctionality and control of the crumpling and unfolding of large-area graphene, Nature Materials 12(4) (2013) 321–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Chen P-Y, Liu M, Wang Z, Hurt RH, Wong IY, From Flatland to Spaceland: Higher Dimensional Patterning with Two-Dimensional Materials, Advanced Materials 29(23) (2017) 1605096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bouras N, Madjoubi MA, Kolli M, Benterki S, Hamidouche M, Thermal and mechanical characterization of borosilicate glass, Physics Procedia 2(3) (2009) 1135–1140. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.