Abstract

We report a case of an elderly male who has undergone right radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Six months later, he presented with gradually progressive low backache and mild lower limb weakness. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT) was done that revealed a suspected area of mild metabolic activity in the spinal cords at the L1–L2 vertebral level. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed intramedullary spinal cord metastasis (ISCM). Solitary ICSM is a rare presentation of RCC on FDG PET-CT, and only a few case reports exist in the literature. This case highlights that adequate clinical history and careful examination of the PET images may reveal it.

Keywords: 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography, intramedullary spinal cord metastasis, renal cell carcinoma

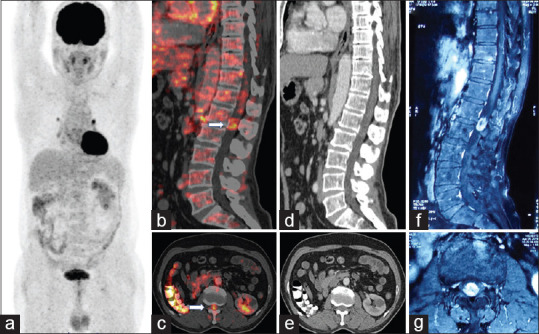

A 65-year-old elderly male underwent right radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. Six months later, patients presented with progressive low backache. Because of suspicious of the skeletal metastases, patients referred for an 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scan. On PET-computed tomography (PET-CT), there was a suspicious area of mild uptake (SUVmax 2.9) in the spinal cord with no significant CT abnormality [Figure 1]. The rest of the body was unremarkable for metastatic disease. The patient underwent contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine that revealed ICSM at the level of the L1–L2 vertebral level. The patient was given stereotactic radiotherapy for the lesion.

Figure 1.

(a) 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography Maximum intensity image is unremarkable apart from the absence of the right kidney and few mediastinal lymph nodes. (b and c) Saggital and axial fused positron emission tomography/computed tomography images show a focal area of mild uptake in the spinal cord at the level of L1 vertebrae. (d and e) Corresponding sagittal and coronal images of computed tomography that are unremarkable. Fluorodeoxyglucose and T1-weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (f and g) in sagittal view, and axial view reveals a well-defined intensely enhancing intramedullary lesion at the L 1–2 level

Metastatic neoplasms involvement of the spine itself is uncommon, and intramedullary spinal cord metastases (ISCMs) are rare. Lung primary is the most frequent cause of the ISCMs followed by the breast 11%–14%, kidney 6%–9%, colorectal 3%–5%, melanoma 6%–9%, lymphoma 4%, and others.[1] They are often asymptomatic, and more than half of patients have concomitant leptomeningeal and brain metastases.[2] Most of the patients have systemic metastasis at the time of diagnosis.[3] Three possible pathological mechanisms have been postulated for ISCMs. One is an arterial pathway which is assisted by the coexisting lung and brain metastasis. Another path is through Batson's venous plexus, which allows retrograde transportation to the spinal cord. The third mechanism is a direct invasion of metastatic tumor cells from the spinal extradural space, cerebrospinal fluid, or nerve roots.[2] The most common presentation is weakness (91%) followed by sensory loss (79%), sphincter dysfunction (60%), back and radicular pain (38%).[1,2,4]

The primary role of PET-CT is the suspected recurrence in to disclose the various metastatic sites. It may play a role in ISCMs by providing metabolic activity of the lesion and reducing other diagnostic concerns such as necrosis and infarction.[5] FDG PET images may not be able to differentiate it from an epidural tumor due to a lack of sufficient image resolution. A gadolinium-enhanced MRI is needed to establish such localization and confirmation. Mostardi et al., in a large series (ten patients with 13 ISCM), correlate the PET and MRI features of the ISCMs. Larger lesions with more edema are likely to be visible on PET. The author suggested that the spinal cord should be explicitly assessed on PET for evidence of ISCMs to provide a timely and accurate diagnosis.[6] Reporting physicians must be aware of the physiological uptake in the cervical spinal cord peaking at the C4 level and in the lower thoracic spinal cord peaking at the T11–T12 segments to avoid misinterpretation.[7]

Therapeutic options for ISCMs include microsurgical excision, stereotactic radiotherapy, chemotherapy, palliative therapy, and particularly steroids.[8] ISCMs have a poor prognosis as most of the patients have a systemic spread of disease. Grem et al. found that more than 80% of patients died within 3 months.[9] However, few patients have shown a better prognosis.[3]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient (s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initial s will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Potti A, Abdel-Raheem M, Levitt R, Schell DA, Mehdi SA. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases (ISCM) and non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC): clinical patterns, diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Lung Cancer. 2001;31:319–23. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalayci M, Caǧavi F, Gül S, Yenidünya S, Açikgöz B. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: diagnosis and treatment-An illustrated review. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2004;146:1347–54. doi: 10.1007/s00701-004-0386-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weng Y, Zhan R, Shen J, Pan J, Jiang H, Huang K, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review of the literature. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:7485020. doi: 10.1155/2018/7485020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasser T, Sandalcioglu IE, El Hamalawi B, van de Nes JA, Stolke D, Wiedemayer H. Surgical treatment of intramedullary spinal cord metastases of systemic cancer: functional outcome and prognosis. J Neurooncol. 2005;73:163–8. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-4275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poggi MM, Patronas N, Buttman JA, Hewitt SM, Fuller B. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: detection by positron emission tomography. Clin Nucl Med. 2001;26:837–9. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mostardi PM, Diehn FE, Rykken JB, Eckel LJ, Schwartz KM, Kaufmann TJ, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: visibility on PET and correlation with MRI features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:196–201. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt G, Li XF, Jain A, Sharma VR, Pan J, Rai A, et al. The normal variant (18) F FDG uptake in the lower thoracic spinal cord segments in cancer patients without CNS malignancy. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;3:317–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalita O. Current insights into surgery for intramedullary spinal cord metastases: A literature review. Int J Surg Oncol. 2011;2011:989506. doi: 10.1155/2011/989506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grem JL, Burgess J, Trump DL. Clinical features and natural history of intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. Cancer. 1985;56:2305–14. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851101)56:9<2305::aid-cncr2820560928>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]