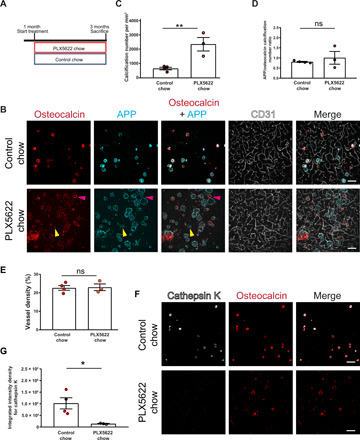

Fig. 5. Pharmacological ablation of microglia aggravates vascular calcification.

(A) Experimental setup of the pharmacological ablation of microglia. One-month-old mice (Pdgfbret/wt, Pdgfbret/ret, or C57BL6) were fed PLX5622 or control chow for 2 months. Mice were euthanized at 3 months of age. (B) Vessel-associated calcifications, visualized by osteocalcin (in red) and APP staining (in cyan), are increased in Pdgfbret/ret compared to control chow–fed Pdgfbret/ret animals. Blood vessels are visualized using CD31 staining (in white). Note that some calcifications in PLX5622-treated Pdgfbret/ret mice are only positive for APP (yellow arrowheads), whereas others are positive only for osteocalcin (magenta arrowheads). (C) Quantification of calcification number in Pdgfbret/ret mice administered PLX5622 or control chow (unpaired two-tailed t test; **P = 0.0087). (D) Ratio between APP- and osteocalcin-positive calcifications after PLX5622 and control chow treatment. (E) Quantification of vessel density in Pdgfbret/ret mice with administered PLX5622 or control chow (unpaired two-tailed t test; P = 0.8782). (F) Cathepsin K (in white) deposition in calcifications (in red) in Pdgfbret/ret mice is reduced after PLX5622 treatment. (G) Quantification of cathepsin K intensity from immunohistochemical stains in (F) (unpaired two-tailed t test; *P = 0.0276). Control chow, n = 4; and PLX5622 chow, n = 3. Scale bars, 100 μm (B and F). ns, not significant. All data are presented as means ± SEM.