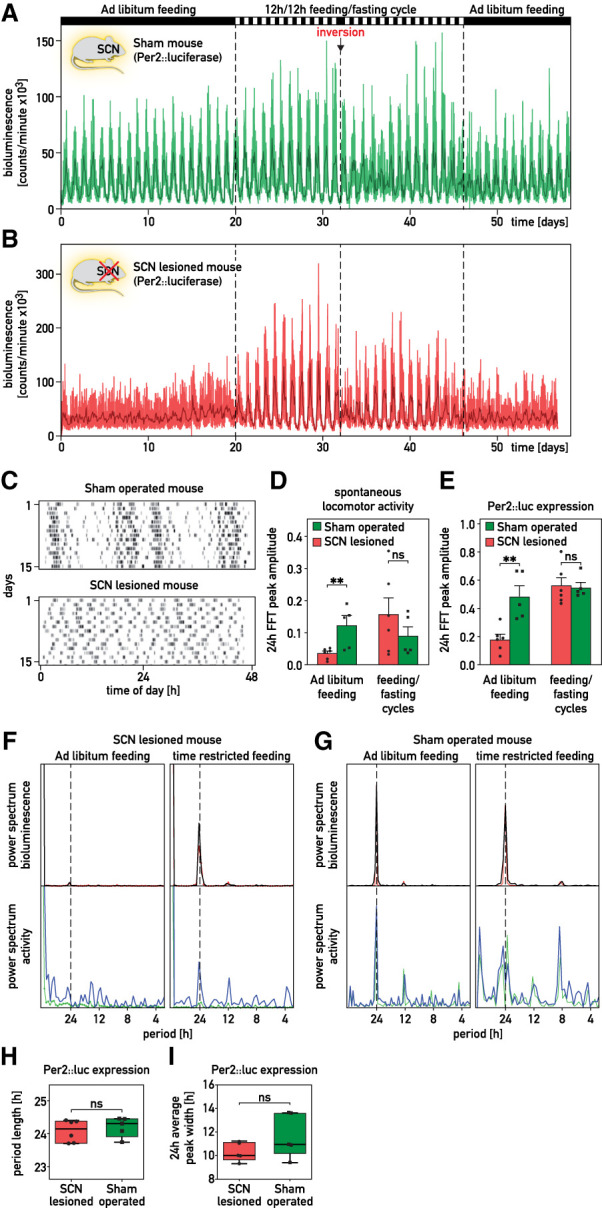

Figure 2.

The SCN is required for the synchronization of peripheral clocks among organs. (A,B) Whole-body bioluminescence for sham-operated (A) and SCN-lesioned (B) Per2::luc mice kept in constant darkness. The feeding regimens are reported above the graphs. The spontaneous locomotor activities of the animals are shown in Supplemental Figure S2A,B. (Thin lines) Raw data (1 min photon counts), (bold lines) 120-min time-binned traces. (C) Actograms of spontaneous locomotor activity of the sham-operated mouse used in A and the SCN-lesioned mouse used in B. After surgery, mice were housed in 12-h/12-h light/dark (LD) cycles and then recorded during 15 d in constant darkness (D/D). (D,E) Amplitude of the FFT peak in the circadian range (≈24 h) of locomotor activities (D) and of Per2::luciferase expression (E) of SCN-lesioned and sham-operated mice subjected to different feeding regimens (means ± SEM, n ≥ 5 per group). (F,G) Periodograms (FFT analysis) of bioluminescence and locomotor activity recorded for the sham-operated mouse displayed in A and the SCN-lesioned mouse displayed in B. (Red and green lines) Raw data (1-min counts), (black and blue lines) integrated data over 120 points. (H,I) Period length from FFT analysis (H) and average oscillation width (I) in sham-operated and SCN-lesioned animals subjected to feeding–fasting cycles. Whiskers of the box plots range from the minimum to the maximum values. The median values are indicated by the horizontal segment within the box, n ≥ 5 per group. Statistical tests for D, E, H, and I were two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. (**) P < 0.01, (ns) nonsignificant.