Abstract

Introduction

In the last decade, there has been a renewed interest in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) preservation surgeries in the younger patients. Several ACL preservation techniques such as primary repair, augmented repair, and scaffold repair have been described based on the particular tear type and pattern. The purpose of this study was to determine the distribution of tear patterns in young patients presenting with an acute ACL injury.

Methods

A prospective observational study was performed at two tertiary children’s hospitals. Patients under 18 years undergoing ACL reconstruction within 8 weeks of initial injury were included from 2017 to 2019. Tear patterns were classified by two orthopedic surgeons from each of the two centers during arthroscopic ACL reconstruction into 4 types: I. Avulsion off the femur, II. <10% of total ACL length tear from femoral end, III. Mid-substance tear and IV. Single bundle tear. For reliability, the four surgeons classified ACL injury (2 rounds each) based on de-identified intraoperative videos of 33 randomly selected surgical ACL cases. Inter and intra-rater reliability studies were calculated using Kappa statistics.

Results

224 patients (123 males, 101 females) with mean age of 16 (range: 9-18) years were enrolled in this study. Fifty-seven (25%) patients reported contact injury while 167 (75%) reported non-contact. Isolated ACL injury was recorded in 70 (31%) patients, while concomitant injuries were recorded in 154 patients (69%). The most common associated injury was lateral meniscus tear (35%), followed by lateral and medial meniscus tears (20%). According to our classification, 31 (14%) patients were Type I, 30 (13%) were Type II, 139 (62%) were Type III, 18 (8%) were Type IV. The intra-rater reliability was excellent for 2 reviewers, good for 1 and marginal for another. The overall inter-rater reliability for all 4 reviewers was marginal for both readings. There was no statistical difference in the occurrence of type of tear based on the mechanism of injury (contact vs non-contact) or age of the patients.

Conclusions

This is the first multicenter study using an arthroscopic assessment to classify the location of ACL tear in the young population. It gives us further insight on the possible application for surgeries to preserve the ACL in this group. Larger studies incorporating these findings with MRI evaluation and ACL repair techniques are needed to confirm the utility of this information to decide the eligibility for repair in pediatric patients.

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament, Adolescent sports injury, ACL tear, ACL reconstruction, ACL repair

1. Introduction

There has been an increase in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries diagnosed in the pediatric and adolescent population, which can be explained by increase in youth sports specialization along with improved imaging modalities.1 Given the difficulty with nonoperative treatment in this population and the risk of recurrent instability causing further damage to the knee, ACL reconstruction is now considered the standard treatment for ACL tears in the pediatric patients.2,3

ACL reconstruction in the skeletally immature patient carries its own set of complications such as: growth arrest due to injury to the physis,4,5 re-rupture or contralateral ACL tear,6, 7, 8, 9 and early onset of osteoarthritis.10,11 For these reasons, there has been renewed interest in various surgical techniques which try to preserve and heal the native ACL.12 These ACL preservation surgeries consist of two broad categories-primary repairs with or without augmentation for proximal tears at the femoral insertion and biologic scaffold-assisted repair for mid-substance tears. The proximal primary repair techniques have yielded good results in the pediatric, adolescent and adult population.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Very recently, prospective trials for mid-substance ACL tears undergoing primary repair with biologic scaffolds have shown promising early outcomes.19,20

With good results shown in early ACL preservation studies and its potential benefits for younger patients, it is important to know the incidence of different tear patterns to help with deciding the most appropriate surgical plan. Studies are trying to find the eligibility of tears which can undergo repair.21 With this in mind, our study was performed to determine the distribution of different ACL tear locations in the young patients using arthroscopy and evaluate the possible role of demographics and mechanism of injury on this distribution.

2. Methods

After both institutional review boards’ approval, this prospective observational study was performed at two tertiary children’s hospitals. Patients under 18 years old undergoing ACL reconstruction within 8 weeks of initial injury were included from April 2017–2019. Patients who were undergoing revision ACL surgery and multi-ligamentous injuries were excluded. Distal bony avulsion fractures were excluded as these were treated as tibial eminence fractures. During arthroscopic surgery, ACL tear locations were graded during arthroscopic surgery by four fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeons, two from each of the two centers. For reliability, the four surgeons classified ACL injury (2 rounds each) based on de-identified intraoperative videos of 33 randomly selected surgical cases from the study cohort. Inter and intra-rater reliability studies were calculated using Kappa statistics (over 0.75- excellent, 0.40 to 0.75- fair to good, and below 0.40 as marginal) and summarized with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

During the arthroscopic evaluation, the ACL tear location was objectively assessed using a standard arthroscopic probe with a 5 mm tip. Based on the tear pattern, the proximal end of the torn ACL was identified and the length of the proximal part of the stump was measured comparing it to the tip of the probe. We approximated the percentage of the proximal stump as compared to the length of the ACL and critically reviewed to confirm tear location. If an elongated stretched-out ACL was encountered with no obvious proximal stump, the middle of the elongated portion was defined as the tear location.

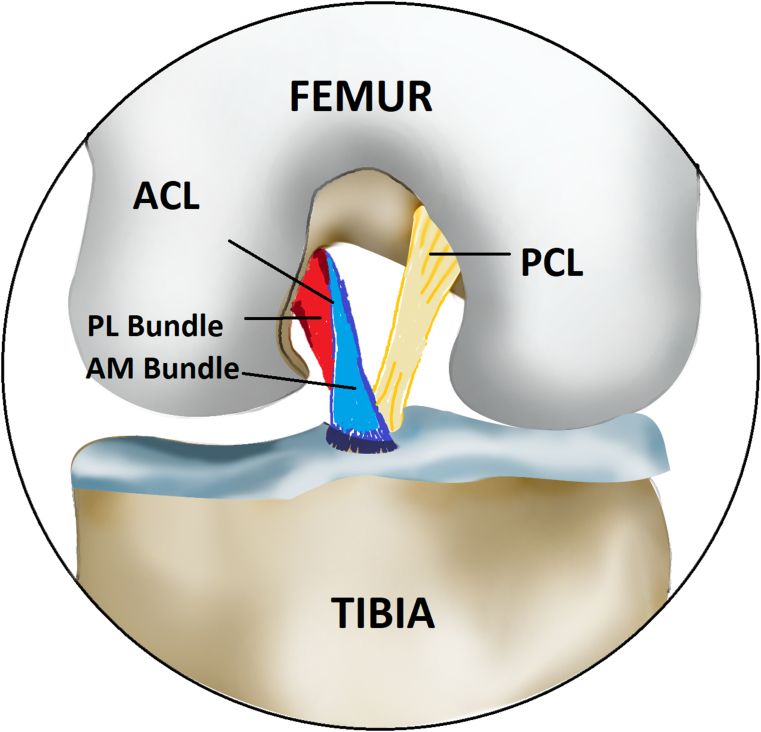

ACL tears were classified as one of the following tear types (Table 1) as compared to a representative illustration of the normal knee (Fig. 1): proximal avulsion (type I, Fig. 2, Fig. 3) which included soft tissue or bony avulsions, proximal tear with 10% or less of the ACL stump remaining on the femoral end (type II, Fig. 4), mid-substance tear with more than 10% of the ACL stump remaining on the femoral end (type III, Fig. 5, Fig. 6), and single bundle tear (type IV, Fig. 7). Tears that could not be classified were labelled as others - type V (Table 1).

Table 1.

Arthroscopic pediatric ACL Tear Type Classification System.

| Tear Type | Description | Tear location |

|---|---|---|

| Type I | Proximal avulsion | Off the femur |

| Type 2 | Proximal avulsion | Length of proximal stump less than 10% of the length of total ACL |

| Type 3 | Mid- substance tear | Length of proximal stump more than 10% of the length of total ACL |

| Type 4 | Single bundle tear | Antero-medial or postero-medial bundle tear |

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the normal knee showing a normal ACL.

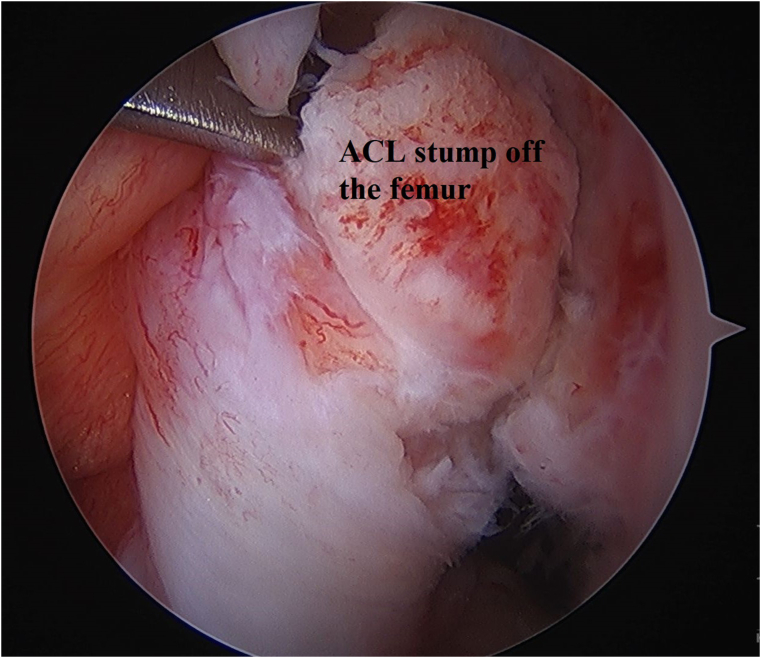

Fig. 2.

Type I tear of the ACL off the femoral end.

Fig. 3.

Arthroscopic picture showing a type 1 tear off the femur.

Fig. 4.

Type 2 tear proximal avulsion of the ACL with length of proximal stump less than 10% of the length of total ACL.

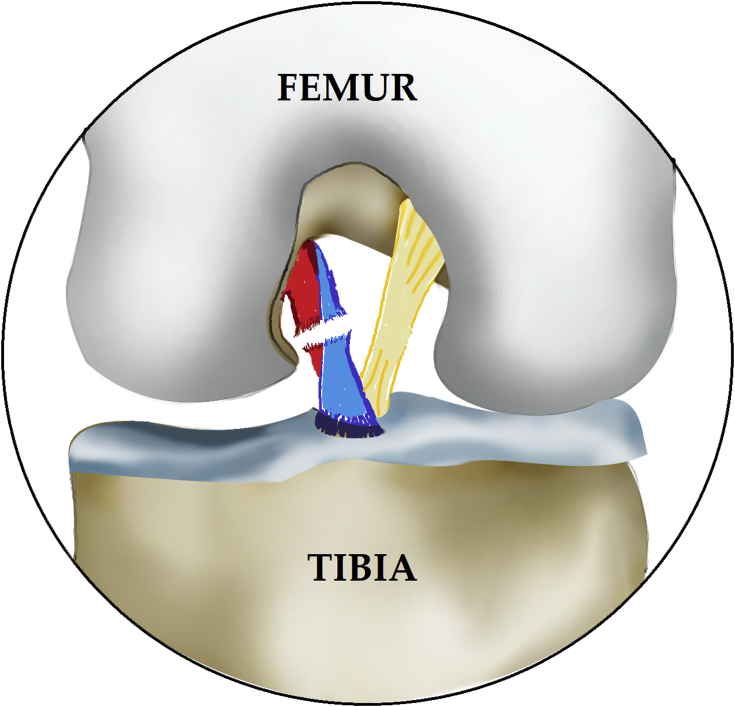

Fig. 5.

Type 3 Mid-substance tear of the ACL.

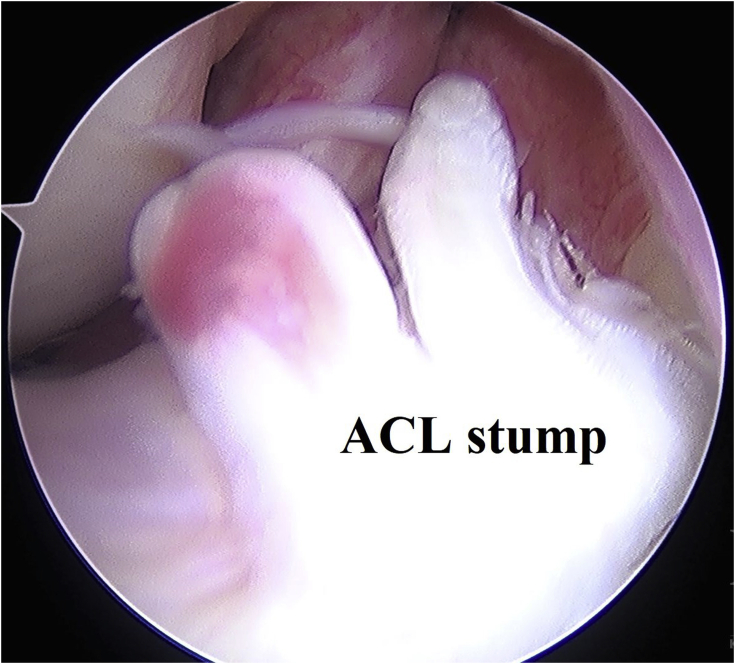

Fig. 6.

Arthroscopic picture of a mid-substance tear.

Fig. 7.

Single bundle tear of the ACL.

After discussion of the design and implementation of this classification system, four fellowship-trained pediatric orthopedic surgeons who perform ACL surgeries at their respective hospitals graded all ACL tear locations as described. Additional data collected from the patient electronic medical records were age, sex, weight height, laterality, associated injuries and injury mechanism (contact vs non-contact).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software; Kruskal Wallis test and Fisher exact tests were used to compare different classification groups and the incidence of different tear locations in different subgroups. We used Kappa statistics to measure the agreement of the first time and second time read for each observer separately and Fleiss’s Kappa statistics to measure the agreement across those observers. According to the guidelines of agreement levels: Kappa over 0.75 was considered as excellent, 0.40 to 0.75 as fair to good, and below 0.40 as marginal.

3. Results

224 patients (123 males, 101 females) with mean age of 16 (range 9-18) years and mean body mass index (BMI) 26 (16–54) lbs./in2 were included in this study from January 2017 to April 2020. 57 (25%) patients reported contact injury while 167 (75%) reported non-contact. Isolated ACL injury was recorded in 70 (31%) patients while concomitant injuries were recorded in 154 patients (69%). The most common associated injury was a lateral meniscus tear (35%), followed by lateral and medial meniscus tears (20%).

According to our classification, 31 (14%) patients were Type I tears with ACL avulsion off the femur, 30 (13%) were Type II with less than 10% proximal ACL stump, 139 (62%) were Type III which consisted of mid-substance ACL tears, 18 (8%) were Type IV which were single bundle ACL tears. 6 (3%) were tears that could not be classified - Type V. Comparing different classification groups, analysis did not show any difference between gender (p = 0.31), Skeletal maturity (p = 0.77), laterality (p = 0.1) or mechanism of injury (0.9). BMI did not have significant differences among different classification groups. (p = 0.88). The intra-rater reliability was excellent for 2 reviewers, good for 1 and marginal for another. The overall inter-rater reliability for all 4 reviewers was marginal for both readings (k = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.23–0.44; k = 0.26, 95%CI: 0.16–0.35 respectively).

4. Discussion

Historically, Sherman et al.22 were the first to categorize adult ACL tears into 4 tear types. As the majority of patients undergo an ACL reconstruction regardless of their tear type, there has been little subsequent research to further classify ACL tear type as it did not impact treatment decisions. However, in the past decade, there has been renewed interest in ACL preservation surgeries (primary repair, augmented repair, repair with biologic scaffold) with promising early results for various techniques.14,16, 17, 18, 19, 20,23,24 The aim of ACL preservation surgery is to maintain and heal the ACL tissue which can potentially avoid the complications associated with ACL reconstruction in young patients like injury to the growth plate,4,5 high rate of re-rupture of ACL6, 7, 8, 9 and inability to avoid radiographic and clinical progression to early osteoarthritis.3,10 Repair of the ACL is being revisited25,26 as it is hypothesized that by preserving and repairing native ACL tissue is a key paradigm shift in the treatment of ACL injuries.12 Studies are trying to find out identify candidates who can undergo a repair rather than ACL reconstruction.21 Our study arthroscopically classifies ACL tears based on the location of the tear in the young population, with the ultimate goal being to help identify those patients who may be eligible for ACL preservation surgery. We are not aware of any other multi-center study utilizing an arthroscopic assessment to classify ACL tear location in this population. Another important finding of this study was that age, sex and injury mechanism did not play an important role in tear location distributions in our cohort.

In our study, the overall incidence of type I proximal ACL avulsions/tears was 14%. This is similar to a recent MRI based study which showed a 15% incidence of proximal avulsions.27 Our study results can be compared with clinical studies reporting the percentage of patients eligible for arthroscopic primary repair of the proximally avulsed ACL (i.e. Type I in our study). In another study on young patients,13 the authors found in their pediatric cohort that 11% (5/46) were repairable. A couple of other studies reported the incidence of the eligibility for primary repair of proximal avulsions (6%–11%) in adult patients.23,28 This percentage is slightly less than our study (14%). Our study gives insight to the ACL surgeon pre-operatively about the proportion of young patients who might be eligible for potential surgery to preserve the ACL, such as primary repair (type I), repair with biologic or synthetic augmentation (type II), repair utilizing a biological scaffold (type III), or single bundle reconstruction/augmentation (type IV).29,30

A previous study27 which classified ACL tears based on MRI showed that Type I tears were seen in 15% (all soft tissue avulsion), type II in 23%, type III in 52%, type IV in 1%, and type V in 8% of patients (1% soft tissue avulsion and 7% bony avulsion). These findings are similar to our study. In their study, no patients with tears of the anteromedial or posterolateral ACL bundle were identified as it might be difficult to ascertain that on MRI only; in fact, the authors in that study recommended an arthroscopic classification for better and reliable determination of the tear which our study has been able to achieve.

In a previous MRI study,27 the incidence of tibial bony avulsions (which they classified as type V) was found to be high in the youngest group of patients aged 6–10 years (93%). We have not included these in our classification system as we believe that those comprise of tibial eminence/spine avulsion fractures and should be considered a separate injury and not a type of ACL tear.

Our study has some limitations. Skeletal immaturity (<12 years for girls and <14 years for boys) was assessed based on chronologic age at the time of injury and not on skeletal age. Even with careful arthroscopic visualization, the determination of exact type of tear can be challenging. There is a possibility that overlap of tear patterns can occur (especially type I or type II injuries for tears around proximal end of the torn ACL). The above-mentioned factors likely affected the incidence of tear types and the inter-observer variability. However arthroscopic probing is more reliable way to determine the exact tear pattern than an MRI as the surgeon is actually visually confirming the findings. We recommend larger multi-center studies in young patients to validate our findings and classification which can be valuable in guiding preoperative discussions and surgical preparation.

5. Conclusion

This study gives an arthroscopic assessment of the tear patterns of acute ACL injuries in young patients. With renewed interest in various ACL preservation and augmentation techniques a classification system for pediatric ACL tears based on their location can guide with surgical planning. Our classification system provides a step to achieve this goal. It showed overall good intra-observer reliability. Further prospective studies are needed to correlate our arthroscopic findings and further assess the incidence of various tear types in this population.

Sources of support (if applicable)

None.

Authors’ contribution

Indranil Kushare: Responsible for initiation of the concept and study, methodology, data collection, manuscript writing, editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Kevin Klingele: Involved in investigation and methodology, data documentation, manuscript writing, reviewing and editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Matt Beran: Involved in literature review, investigation and methodology, data documentation, manuscript writing and editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Mohit Jain : Initiation of concept, investigation and methodology, data collection, reviewing and editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Kevin Klingele: Involved in investigation and methodology, data acquisition manuscript writing, reviewing and editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Attia Elsayed: Involved in investigation and methodology, data acquisition, statistical analysis manuscript writing, reviewing and editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Scott McKay: Involved in investigation and methodology, data documentation, manuscript writing, reviewing and editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent statement

No consent as it was a retrospective study.

Declaration of competing interestCOI

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. No conflict of interest is to be declared.

Statement of equal authors’ contribution

We provide assurance that each author fulfills authorship criteria based on the substantial contributions to the study.

References

- 1.Fabricant P.D., Kocher M.S. Management of ACL injuries in children and adolescents. J Bone Jt Surg Am Vol. 2017;99(7):600–612. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner B.C., Yang S., Looney A.M., Gwathmey F.W., Jr. Trends in pediatric and adolescent anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36(5):447–452. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poehling-Monaghan K.L., Salem H., Ross K.E. Long-Term outcomes in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review of patellar tendon versus hamstring autografts. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(6) doi: 10.1177/2325967117709735. 2325967117709735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frosch K.H., Stengel D., Brodhun T. Outcomes and risks of operative treatment of rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament in children and adolescents. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2010;26(11):1539–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.04.077. official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong S.E., Feeley B.T., Pandya N.K. Comparing outcomes between the over-the-top and all-epiphyseal techniques for physeal-sparing ACL reconstruction: a narrative review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(3) doi: 10.1177/2325967119833689. 2325967119833689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webster K.E., Feller J.A. Exploring the high reinjury rate in younger patients undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(11):2827–2832. doi: 10.1177/0363546516651845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiggins A.J., Grandhi R.K., Schneider D.K., Stanfield D., Webster K.E., Myer G.D. Risk of secondary injury in younger athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(7):1861–1876. doi: 10.1177/0363546515621554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paterno M.V., Rauh M.J., Schmitt L.C., Ford K.R., Hewett T.E. Incidence of contralateral and ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury after primary ACL reconstruction and return to sport. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22(2):116–121. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318246ef9e. official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paterno M.V., Rauh M.J., Schmitt L.C., Ford K.R., Hewett T.E. Incidence of second ACL injuries 2 Years after primary ACL reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1567–1573. doi: 10.1177/0363546514530088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Øiestad B.E., Engebretsen L., Storheim K., Risberg M.A. Knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(7):1434–1443. doi: 10.1177/0363546509338827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Porat A., Roos E.M., Roos H. High prevalence of osteoarthritis 14 years after an anterior cruciate ligament tear in male soccer players: a study of radiographic and patient relevant outcomes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(3):269–273. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.008136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahapatra P., Horriat S., Anand B.S. Anterior cruciate ligament repair - past, present and future. J Exp Orthop. 2018;5(1) doi: 10.1186/s40634-018-0136-6. 20-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bigoni M., Gaddi D., Gorla M. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament repair for proximal anterior cruciate ligament tears in skeletally immature patients: surgical technique and preliminary results. Knee. 2017;24(1):40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henle P., Röder C., Perler G., Heitkemper S., Eggli S. Dynamic Intraligamentary Stabilization (DIS) for treatment of acute anterior cruciate ligament ruptures: case series experience of the first three years. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2015;16(27) doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0484-7. 15-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoogeslag R.A.G., Brouwer R.W., Boer B.C., de Vries A.J. Huis in ’t veld R. Acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: repair or reconstruction? Two-year results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(3):567–577. doi: 10.1177/0363546519825878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukhopadhyay R., Shah N., Vakta R., Bhatt J. ACL femoral avulsion repair using suture pull-out technique: a case series of thirteen patients. Chin J Traumatol. 2018;21(6):352–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2018.07.001. Zhonghua chuang shang za zhi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith J.O., Yasen S.K., Palmer H.C., Lord B.R., Britton E.M., Wilson A.J. Paediatric ACL repair reinforced with temporary internal bracing. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(6):1845–1851. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4150-x. official journal of the ESSKA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xavier P.M., Fournier J., de Courtivron B., Bergerault F., Bonnard C. Rare ACL enthesis tears treated by suture in children. A report of 14 cases after a mean 15 years follow-up. Orthop Traumatol Surgery Res: OTSR. 2016;102(5):619–623. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray M.M., Fleming B.C., Badger G.J. Bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair is not inferior to autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction at 2 Years: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(6):1305–1315. doi: 10.1177/0363546520913532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray M.M., Kalish L.A., Fleming B.C. Bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair: two-year results of a first-in-human study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(3) doi: 10.1177/2325967118824356. 2325967118824356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der List J.P., Jonkergouw A., van Noort A., Kerkhoffs G., DiFelice G.S. Identifying candidates for arthroscopic primary repair of the anterior cruciate ligament: a case-control study. Knee. 2019;26(3):619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherman M.F., Lieber L., Bonamo J.R., Podesta L., Reiter I. The long-term followup of primary anterior cruciate ligament repair. Defining a rationale for augmentation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(3):243–255. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiFelice G.S., Villegas C., Taylor S. Anterior cruciate ligament preservation: early results of a novel arthroscopic technique for suture anchor primary anterior cruciate ligament repair. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2015;31(11):2162–2171. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.08.010. official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heusdens C.H.W., Zazulia K., Roelant E. Study protocol: a single-blind, multi-center, randomized controlled trial comparing dynamic intraligamentary stabilization, internal brace ligament augmentation and reconstruction in individuals with an acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: LIBRƎ study. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2019;20(1):547. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2926-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der List J.P., Vermeijden H.D., Sierevelt I.N., DiFelice G.S., van Noort A., Kerkhoffs G. Arthroscopic primary repair of proximal anterior cruciate ligament tears seems safe but higher level of evidence is needed: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent literature. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(6):1946–1957. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05697-8. official journal of the ESSKA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmad S.S., Difelice G.S., van der List J.P., Ateschrang A., Hirschmann M.T. Primary repair of the anterior cruciate ligament: real innovation or reinvention of the wheel? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(1):1–2. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5312-9. official journal of the ESSKA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der List J.P., Mintz D.N., DiFelice G.S. The locations of anterior cruciate ligament tears in pediatric and adolescent patients: a magnetic resonance study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39(9):441–448. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Achtnich A., Herbst E., Forkel P. Acute proximal anterior cruciate ligament tears: outcomes after arthroscopic suture anchor repair versus anatomic single-bundle reconstruction. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2016;32(12):2562–2569. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.04.031. official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der List J.P., DiFelice G.S. Preservation of the anterior cruciate ligament: a treatment algorithm based on tear location and tissue quality. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2016;45(7):E393–E405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der List J.P., DiFelice G.S. Preservation of the anterior cruciate ligament: surgical techniques. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2016;45(7):E406–E414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]