Abstract

High Andean forests harbor a remarkably high biodiversity and play a key role in providing vital ecosystem services for neighboring cities and settlements. However, they are among the most fragmented and threatened ecosystems in the neotropics. To preserve their unique biodiversity, a deeper understanding of the effects of anthropogenic perturbations on them is urgently needed. Here, we characterized the plant communities of high Andean forest remnants in the hinterland of Bogotá in 32 0.04 ha plots. We assessed the woody vegetation and sampled the understory and epiphytic cover. We gathered data on compositional and structural parameters and compiled a broad array of variables related to anthropogenic disturbance, ranging from local to landscape‐wide metrics. We also assessed phylogenetic diversity and functional diversity. We employed nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) to select meaningful variables in a first step of the analysis. Then, we performed partial redundancy analysis (pRDA) and generalized linear models (GLMs) in order to test how selected environmental and anthropogenic variables are affecting the composition, diversity, and aboveground biomass of these forests. Identified woody vegetation and understory layer communities were characterized by differences in elevation, temperature, and relative humidity, but were also related to different levels of human influence. We found that the increase of human‐related disturbance resulted in less phylogenetic diversity and in the phylogenetic clustering of the woody vegetation and in lower aboveground biomass (AGB) values. As to the understory, disturbance was associated with a higher diversity, jointly with a higher phylogenetic dispersion. The most relevant disturbance predictors identified here were as follows: edge effect, proximity of cattle, minimum fragment age, and median patch size. Interestingly, AGB was efficiently predicted by the proportion of late successional species. We therefore recommend the use of AGB and abundance of late successional species as indicators of human disturbance on high Andean forests.

Keywords: aboveground biomass, biodiversity, bosque altoandino, Colombia, cryptic forest degradation, understory

High Andean forests play a key role in providing ecosystem services for neighboring urban settlements. Here, we aimed to identify and understand the effects of anthropogenic perturbations on diversity, composition, and structure of plant communities, as well as aboveground biomass in high Andean forest remnants in the hinterland of Bogotá. We found that the increase of human‐related disturbance resulted in less phylogenetic diversity and in the phylogenetic clustering of the woody vegetation and in lower aboveground biomass (AGB) values. As to the understory, disturbance was associated with a higher diversity, jointly with a higher phylogenetic dispersion. Interestingly, AGB was efficiently predicted by the proportion of late successional species.

1. INTRODUCTION

High Andean tropical montane forests (herein bosques altoandinos) can be found between ca. 2,700 and 3,300 m in the Northern Andes, extending from Venezuela to Ecuador, with considerable levels of species diversity and endemism (Gentry & Ortiz, 1993; Girardin et al., 2014; Killeen et al., 2007; Still et al., 1999; Young, 1992). These forests provide vital ecosystem services to the neighboring cities and settlements, such as the regulation of water fluxes (Armenteras et al., 2003; Chaves & Arango, 1998; Linares & Ríos, 2004; Rangel, 2000) or carbon capture and storage (Brown & Kappelle, 2001; Torres et al., 2012).

Bosques altoandinos have been subjected to extensive anthropogenic transformation across their natural range. In Colombia, large portions of the forest cover were cleared during the past four centuries and turned into agricultural or residential areas, in order to satisfy the growing demand for resources of an increasing human population (Brown & Kappelle, 2001; Cavelier et al., 2001; Etter et al., 2008; Heath & Binswanger, 1996; Sánchez‐Cuervo et al., 2012; Wassenaar et al., 2007). Such a reduction of forest cover can not only lead to loss of biodiversity but also to a lower structural integrity and resilience of the remaining fragments (Mori et al., 2013). Changes in species composition also go along with shifts in functional diversity and biological interactions (Bovendorp et al., 2019; Diaz & Cabido, 2001; Flynn et al., 2011; Petchey & Gaston, 2002, 2007; Poos et al., 2009; Swenson, 2014). Eventually, this affects ecosystem services (González et al., 2011; Menon et al., 2007; Rangel, 2000; Torres et al., 2012).

In the recent past, forest cover has increasingly been monitored using remote sensing techniques. For the Colombian high Andean forests, this has shown modest signs of recovery in some areas (Calbi et al., 2020; Etter, 2002; Rubiano et al., 2017; Sánchez‐Cuervo et al., 2012; but see Anselm et al., 2018). However, remote sensing cannot detect cryptic forms of forest degradation, such as selective logging or understory grazing. Even plot‐based surveys focusing on trees may not reveal such alterations. Yet, cryptic forest degradation has significant impact on soil erosion, successional dynamics, and regeneration, since understory and epiphytic plants are major drivers of ecosystem functioning (Nilsson & Wardle, 2005). Understanding the effects of anthropogenic disturbance on all major forest components, that is, tree, shrub, understory, and epiphyte layers, is therefore essential to elaborate and implement effective strategies for the sustainable management of these forest ecosystems (Battles et al., 2001; Fahey & Puettmann, 2007; Halpern & Spies, 1995; Roberts & Gilliam, 1995). In addition, multiple predictor and response variables should be analyzed simultaneously to properly address disturbance effects within this complex environment.

One of the best areas to study the impact of human‐induced alterations on bosques altoandinos in the northern Andes is the area of Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, which is situated at approximately 2,600 m altitude. With a population of around 9 million inhabitants, Bogotá is by far the largest city in the Andean high montane forest belt, putting tremendous pressure on the surrounding ecosystems. Remnants of high Andean forests near Bogotá are mostly affected by rural activities, which include logging, fires, and agriculture, typically resulting in soil compaction, low fertility, and/or erosion (Armenteras et al., 2003; Linares & Ríos, 2004; Posada & Norden, unpublished results). Bosques altoandinos in the surroundings of Bogotá have mostly been studied using phytosociological analysis of plot inventory data (Avella et al., 2014; Cantillo Higuera & Gracia, 2013; Cleef, 1981; Cortés, 2008; Sturm & Rangel, 1985; Van der Hammen, 2008). Beyond such floristically oriented approaches, few studies have addressed the effects of disturbance on these forest ecosystems. Some preliminary research works on forest succession and regeneration were carried out as thesis works (Acuña, 2013; Restrepo Abadia, 2016). In a recent study, Rodríguez‐Alarcón et al. (2018) found a negative effect of forest fragmentation on functional diversity and aboveground biomass, a first indication that more complex parameters such as functional diversity are indeed related to ecosystem services such as carbon storage. However, studies that simultaneously consider multiple disturbance predictors and different plant communities response variables were so far lacking.

According to the available literature, the most relevant disturbance factors, which variation proved to be significantly related to differences in forest species composition or diversity metrics, are as follows: age of forest fragment (Köster et al., 2009; Laurance et al., 2006), proximity to houses or roads and people and livestock density (Ribeiro et al., 2015, 2016), edge effect, and proximity to pastures (Parra Sánchez et al., 2016; Werner & Gradstein, 2009), as well as forest cover fragmentation metrics (Fahrig, 2003; Hertzog et al., 2019; Laurance et al., 2006). Nonetheless, it has not yet been tested whether these factors would be still relevant when a larger number of variables are considered simultaneously. For this reason, we conducted a comprehensive integrated assessment of the potential effects of multiple environmental and disturbance variables on the taxonomic, phylogenetic, and functional diversity of the two main forest layers (tree layer and understory) and on epiphytes cover.

We therefore hypothesized that anthropogenic disturbance as a whole, understood as a composite variable sensu Paine et al. (1998), affects the composition, and aboveground biomass of bosques altoandinos, with impacts on community diversity metrics, that is, taxonomic, phylogenetic, and functional diversity. We also hypothesized that our comprehensive analysis would identify significant predictor and response variables other than those found in previous studies. We specifically set out to answer three questions: (a) Which environmental and disturbance variables best explain species diversity and composition of tree and understory layers? (b) What are the effects of facilitators (parameters that increase the likeliness of disturbance) and causes (direct sources) of disturbance on species diversity, phylogenetic structure, functional diversity, and aboveground biomass? (c) Which vegetation variables are best indicators of disturbance?

2. METHODS

2.1. Study area

The study area encompasses ca. 4,600 km2 within the Cundiboyacense high plain in the Cordillera Oriental of Colombia, spanning peri‐urban and rural areas of the department of Cundinamarca and the administrative region of the city of Bogotá (Bogotá D.C. or Distrito Capital). The capital region is the most densely populated area of the country, with nearly 9 million inhabitants and approximately 4,500 people per km2 (DANE, 2019). The climate is characterized by isothermality with an annual mean temperature of around 14°C and mean annual precipitation between 600 and 1,300 mm. There are two rainy seasons: from April to June and from September to November, with a drier and warmer season from January to March (Anselm et al., 2020; IDEAM, 2007, 2015). The topography is marked by an extended plain, situated at around 2,600 m, which hosts most of the urban and agricultural area, and steep elevation gradients including mountains of up to 4,100 m altitude. Dominant soils in the study area were classified as Andisols (IGAC, 1985; Etter, 2002; Sturm & Rangel, 1985).

Rural areas in the region are highly influenced by the adjacent city of Bogotá and contiguous suburbs. Hence, sparse remnants of original vegetation are intermixed with secondary forests (Cortés, 2008; Rubiano et al., 2017). These remnants are largely dominated, by trees and shrubs in genera such as Weinmannia, Miconia, Clusia, Hesperomeles, Clethra, Myrcianthes, Myrsine, Gaultheria and Escallonia, various genera of Lauraceae, and Cedrela montana. Hygrophytic communities with prevalence of Drimys granadensis or Hedyosmum or higher elevation heliophyte associations of Gynoxys, Diplostephium, and Vallea stipularis also form part of these ecosystems (Rangel, 2000; Sturm & Rangel, 1985; Van der Hammen, 1998). The forest patches are embedded in a landscape mosaic with cattle pastures and small‐scale cultivation of potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), green beans (Pisum sativum), and cubios (Tropaeolum tuberosum). The size of remaining forest fragments is generally small, and their regeneration is threatened by further fragmentation, invasive species, erosion (Linares & Ríos, 2004), and urbanization (Rubiano et al., 2017).

2.2. Plot setup

Due to the usually small size of forest fragments, we used a plot size of 20 × 20 m (0.04 ha) as established in the framework of the Rastrojos project (Acuña, 2013; Hurtado‐Martilletti et al., 2020; Muñoz‐Camacho et al., 2017). We complemented the data from the tree layer assessments of 20 plots obtained from the Rastrojos project with data from 12 plots set up and assessed during this study. In addition to the tree layer data, we also assessed the understory layer, and epiphyte cover in the totaling 32 plots, which are located in six administrative regions of Bogotá D.C. and Cundinamarca (Figure 1; Appendix A1). We aimed for a widely scattered position of plots in order to represent the landscape (e.g., including differently inclined slopes). Our sampling design was influenced by the distribution of available and accessible fragments. Plot locations belonged to privately owned protected areas and farms, for which we obtained the required permits of entry from the corresponding owners.

FIGURE 1.

Study area and plot locations. (a) Colombia with Bogotá Capital Department in black; (b) manually vectorized forest fragment in Guatavita; (c) Typical aspect of forest fragment in the study area: (d) Bogotá Capital Department and plot locations. Base map modified from Bing and OSM

2.3. Macro‐environmental variables

For each plot, macro‐environmental variables were compiled from different sources in QGIS 2.18.12 “Las Palmas” (QGIS Development Team, 2018). Altitude, slope, and aspect (northness and eastness) were derived from an Aster Digital elevation model of the study area; for this, ASTGTM2_N04W075, ASTGTM2_N05W075, ASTGTM2_N05W074, and ASTGTM2_N04W074 data products were retrieved from the NASA Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC; https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/tools/data‐pool, NASA/METI/AIST/Japan Spacesystems & U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team, 2009). Mean annual precipitation and mean and maximum temperature data for the period 1981–2010 were obtained from the IDEAM meteorological station closest to each plot (http://www.pronosticosyalertas.gov.co/mapas‐graficos‐tiempo‐clima/indicadores‐climatologicos). Mean population density was extracted in two buffers (radius 1 km and 5 km) around the plots from the worldpop database for South America at 1 ha resolution (https://www.worldpop.org, Sorichetta et al., 2015). A complete list of all macro‐environmental variables can be found in the Appendix A2.

2.4. Tree and shrub layer assessment

Following the protocol of Hurtado‐Martilletti et al. (2020), for every woody plant with basal diameter > 5 cm (measured at 5 cm from the ground—DAH: Diameter at “ankle” height), we recorded its DAH, DBH and visually estimated tree height, a method that proved to be quite precise for lower canopies such as the ones studied here (Silva et al., 2012). Plant material was collected and identified with the available literature (Gentry & Vasquez, 1993; Trelease & Yuncker, 1950; or webpages: https://plantasdecolombia.com), by comparison with herbarium specimens, digitized specimens available online (JBB: http://herbario.jbb.gov.co; COL: http://www.biovirtual.unal.edu.co/en/collections/search/plants), or with additional help from local experts. Specimens were deposited in the herbarium of the Jardín Botánico de Bogotá José Celestino Mutis (JBB); high‐resolution digital specimen images can be provided upon request; and a plot‐resolved list of vouchers can be found in the Appendix A3.

2.5. Understory assessment

In each 20 × 20 m plot, eight 1 × 1 m quadrants (with marked 10 cm subgrids) were placed randomly. All vascular plants, including tree seedlings, were recorded, and mean height and total cover (the sum of all individuals cover) were measured for every species in each quadrant. When available, fertile material was collected and deposited in the JBB. Additionally, cover of bare soil, leaf litter, bryophytes, lichens, and coarse woody debris was visually estimated for every quadrant.

2.6. Epiphyte cover

In each plot, we sampled 40 randomly selected trees to estimate the epiphyte cover. Categorical cover classes (ranging from 0 to 3) were assigned to each of five major epiphyte groups (bryophytes, lichens, ferns, bromeliads, and orchids), separately for trunk and canopy branches.

2.7. Functional traits and functional diversity

Three leaf functional traits (specific leaf area: SLA; leaf thickness: LT; and leaf dry matter content: LDMC) were measured for each tree species following the protocols provided by Pérez‐Harguindeguy et al., (2013). Five leaves were collected from each of up to three different individuals per species and stored in wet paper for at least 12 hr, then weighted (petiole included). LT was measured with a digital micrometer, and a digital scan of the fresh leaves was taken with a Hewlett‐Packard F4280 scanner. Leaf area was calculated with ImageJ 1.8.0 (Schneider et al., 2012). Leaves were oven‐dried at 60°C until constant weight and weighted; SLA was then calculated as one‐sided area of a fresh leaf divided by its dry mass, expressed in cm2/g. LDMC was calculated as the dry mass (mg) divided by its fully hydrated fresh mass (g), and expressed in mg/g. Additionally, wood density (WD) was obtained from Rodríguez‐Alarcón et al. (2018) and the global wood density database (Chave et al., 2009) for all tree species or, depending on availability, at genus or family level estimates, using the R package biomass (Réjou‐Méchain et al., 2018) in R Studio (R Core Team, 2018). The traits used to estimate functional diversity were SLA, LDMC, LT, WD, maximum recorded height in the plots, and life form (tree or shrub). The final trait database was completed with data from the Rastrojos project including data from published reports (Muñoz‐Camacho et al., 2017) and Posada (unpublished results).

To reduce skewness, traits were log10‐transformed and computation of functional divergence, functional dispersion, functional richness, functional evenness, and Rao's quadratic entropy (FDiv, FDis, FRic, FEve and Rao's Q) was performed as indicated in Villéger et al. (2008), using the R package FD (Laliberté & Legendre, 2010; Laliberté et al., 2014). We specified “corr + lingoes, m = 3” to reduce dimensionality. Functional diversity (FD) index (Petchey & Gaston, 2002) was calculated as the total branch length of a functional dendrogram generated on a distance matrix of traits with the R function hclust, using the PD function in the R package picante (Kembel et al., 2010). We decided to compute functional diversity according to the framework proposed by Mason et al. (2005) and Villéger et al. (2008). The calculated indices provide independent information about the position and relative abundances of species in a multidimensional functional space, allowing for a more detailed examination of the mechanisms linking biodiversity to ecosystem function (Villéger et al., 2008).

2.8. Landscape metrics

A Landsat 8 raster was downloaded from the US Geological Survey and processed in QGIS with the SCP plugin (Congedo, 2016) to obtain a land cover map. Landscape metrics refer to the size, shape, configuration, number, and position of land‐use patches within a landscape and were obtained for the forest class within a 1,000 m diameter buffer zone around the plots with the LecoS plugin (Jung, 2013).

Additionally, fragments of forests were manually vectorized and the area was calculated on a prepared Bing aerial map obtained through the Openlayers plugin (see Figure 1 for an example). Distance to closest roads was calculated with the NNJoin plugin on a shapefile downloaded from the DANE Web site (2018). Also, the type of closest road (main, secondary, or track) was noted. Distances to closest houses or tracks were manually measured on the map. Presence or absence of cattle or active cultivated fields in different buffers (0 m, 50 m, 100 m, or 500 m radius) was surveyed in the field. A complete list of all landscape metrics can be found in the Appendix A2.

Minimum age of the forest cover of each plot was estimated through the visual analysis of 43 aerial pictures of the plot locations acquired from the IGAC (Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi, Bogotá; a detailed list of images can be found in the Appendix A4). The pictures ranged from the year 1940 to 2000 at roughly 10‐year intervals. We searched for available pictures from our plot locations and visually located the plots on the nongeoreferenced images. For each plot, we estimated the minimum age based on the oldest documented continuous occurrence of closed forest. A further analysis of forest cover change during the last seven decades around the study plots, carried out on the same set of aerial pictures, is presented in Calbi et al. (2020).

2.9. Community composition and structural variables

Based on the available literature (Cleef, 1981; Cortés, 2008; Cuatrecasas, 1958; Sturm & Rangel, 1985; Van der Hammen, 1998), tree layer species were classified either as late successional slow‐growing, early successional fast‐growing, exotic, or “other” (see Appendix A3 for details). Additionally, understory exotic species cover was calculated. The number of species and the relative proportion of individuals (in case of trees) or the percent cover (in case of the understory) of exotic species were used as indicators of disturbance versus conservation. Variance of tree DBH and height was also computed across all trees within each plot, together with the overall number of tree individuals, stems, stems per tree, and the percentage of large trees (DBH > 30 cm). Mean understory height and cover was calculated, as well as mean epiphytes cover.

The Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality within a distribution widely used in forestry (Bourdier et al., 2016; Latham et al., 1998; Lexerød & Eid, 2006), was calculated in each plot for stem basal areas with the gini function in the R package reldist (Handcock, 2016).

2.10. Taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity

Alpha‐diversity indices (Shannon's diversity, Simpson's and Pielou's evenness) were computed for each plot with the R package vegan (Oksanen et al., 2013). Phylogenetic community structure was assessed on the basis of a published angiosperm supertree (Phylomatic tree R20120829, available at https://github.com/camwebb/tree‐of‐trees/blob/master/megatrees/R20120829.new). First, a regional pool tree was generated with the Phylomatic webtool (Webb & Donoghue, 2005), and then, branch lengths were assigned with the bladj algorithm in the software Phylocom 4.2 (Webb et al., 2008), using the wikstrom.ages file (Wikström et al., 2001). Phylogenetic diversity (PD), mean pairwise distance (MPD), mean nearest taxon distance (MNTD), and their standardized counterparts (sesPD, sesMPD, and sesMNTD) were calculated for both trees and understory in the R package picante (Kembel et al., 2010). Moreover, abundance‐weighted MPD and MNTD were calculated to account for differences in species abundance (Webb et al., 2011). Four species of the Lycopodiaceae had to be removed from the understory regional pool since the family was not included in the used supertree.

The standardized PD metrics express the difference between observed and average value in units of standard deviation (SD). Positive values indicate phylogenetic overdispersion (co‐occurring species are more distantly related than expected by chance) and negative values phylogenetic clustering (co‐occurring species are more closely related than expected by chance).

2.11. Aboveground biomass

Aboveground tree biomass was calculated with the R package biomass. Field measurements of DBH contained less than 5% missing data, so imputation of missing values was performed with the R package mice (van Buuren & Groothuis‐Oudshoorn, 2011). To balance the missing data in height measurements, a regional diameter–height model was built in biomass. Error propagation was carried out using the AGBmonteCarlo function. Wood density error (errWD) was obtained with the getWoodDensity function as prior values on the uncertainty on wood density values, obtained using the mean sd at the species, genus, and family levels of taxa having at least 10 wood density values in the Global Wood Density database (Réjou‐Méchain et al., 2017). Height error (errH) was calculated as the RSE resulting from the local height–diameter models, as in Réjou‐Méchain et al. (2017), and diameter measurements propagation error (Dpropag) was set to "chave2004," which assigns a standard important error on 5 percent of the measures, and a smaller error on 95 percent of the trees (Réjou‐Méchain et al., 2018).

Mean stand aboveground biomass (AGB) and 95% credibility interval following the error propagation were calculated with the following equation (Chave et al., 2014):

where AGB = aboveground biomass [kg], WD = wood density [g/cm3], H = height [m], and D = DBH [cm]. Mean AGB per tree was calculated by dividing the total AGB value of each plot by the number of tree individuals.

2.12. Data analysis

2.12.1. Drivers of species composition of tree layer and understory

Presence and abundance of all tree, shrub, and liana species were compiled for each plot. Relative abundance was calculated for tree and understory layer mean cover.

Environmental and disturbance‐related variables as well as calculated diversity and biomass metrics were assigned to one of five categories relative to disturbance: geo‐environmental = predicting, causes = predicting, facilitators (parameters that increase the likeliness of disturbance) = predicting, level (calculated complex parameters of disturbance outcomes) = response, indicators (parameters that indicate directly the degree of disturbance) = response (Appendix A2). For instance, signs of grazing or logging were considered a potential cause of disturbance, whereas the nearest distance to a road was considered a potential facilitator. Diversity indices and biomass estimation were included in the level category.

To filter for dominant variables, we first ordinated the plots based on relative species abundances using nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) in vegan, using the mds function with Bray–Curtis distances, and specifying three as maximum number of axes. Subsequently, we fitted all variables using the envfit function and examined variable ordination scores, in order to identify the variables most strongly correlated with community composition and to assess redundancy. Both predictor and response variables were included in the same analyses, and NMDS was performed separately for tree and understory layer. Second, using Sørensen distances and flexible beta (set to –0.25) as group linkage method (McCune & Mefford, 2015), cluster analysis and subsequently indicator species analysis for each cluster were carried out in PCORD 7 (McCune & Mefford, 2015), in order to further classify community types and their characteristic elements.

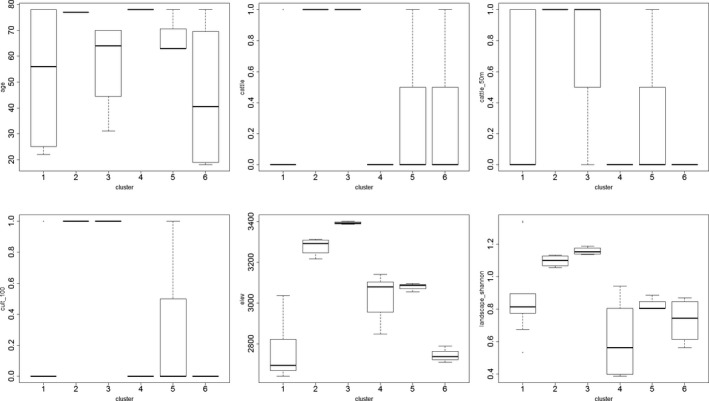

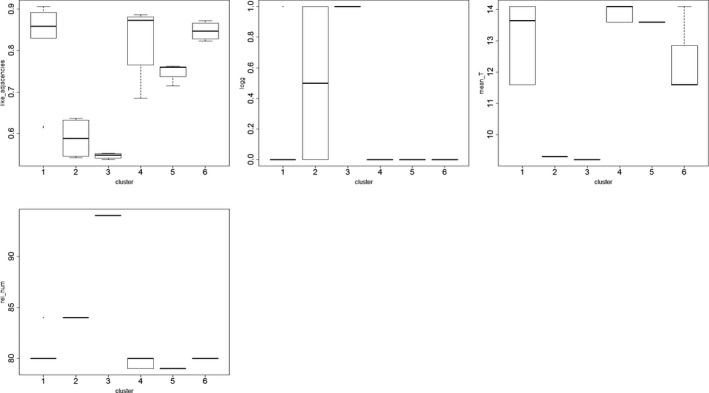

Following this preliminary analysis, we determined a subset of variables that correlated with the main axes above a given threshold (R sq > 0.35; Table 1) and performed either Kruskal–Wallis or parametric ANOVA, depending on the determined conditional distribution, using the clusters as independent variables and the filtered subsets of variables as response variables.

TABLE 1.

Variables (only predictors retained) correlating with axes above R Sq > 0.35 for trees and understory NMDS

| Variable | R sq | p | |

| Trees | elev | 0.84 | 0.001 |

| rel_hum | 0.81 | 0.001 | |

| like_adjacencies | 0.72 | 0.001 | |

| splitting_index | 0.71 | 0.001 | |

| patch_cohesion_index | 0.68 | 0.001 | |

| logg | 0.63 | 0.001 | |

| greatest_patch | 0.63 | 0.001 | |

| largest_patch_index | 0.62 | 0.001 | |

| land_cover | 0.61 | 0.001 | |

| landscape_porportion | 0.61 | 0.001 | |

| overall_core | 0.59 | 0.001 | |

| mean_T | 0.54 | 0.001 | |

| landscape_shannon | 0.53 | 0.001 | |

| effective_meshsize | 0.52 | 0.002 | |

| landscape_division | 0.52 | 0.002 | |

| cult_100 | 0.49 | 0.001 | |

| cattle | 0.49 | 0.001 | |

| landscape_simpson | 0.45 | 0.003 | |

| cattle_100 | 0.42 | 0.003 | |

| age | 0.41 | 0.004 | |

| cattle_50m | 0.39 | 0.006 | |

| road_dist | 0.36 | 0.001 | |

| Understory | elev | 0.74 | 0.001 |

| fragment | 0.62 | 0.001 | |

| overall_core | 0.58 | 0.001 | |

| nn_distance | 0.57 | 0.001 | |

| road_dist | 0.55 | 0.001 | |

| edge_density | 0.55 | 0.001 | |

| edge_lenght | 0.55 | 0.001 | |

| m_DBH | 0.54 | 0.001 | |

| like_adjacencies | 0.53 | 0.001 | |

| landscape_pielou | 0.53 | 0.001 | |

| people_density_1km | 0.49 | 0.001 | |

| landscape_simpson | 0.49 | 0.001 | |

| mAGBT | 0.48 | 0.001 | |

| people_density_5km | 0.45 | 0.001 | |

| effective_meshsize | 0.43 | 0.001 | |

| landscape_division | 0.43 | 0.001 | |

| landscape_shannon | 0.43 | 0.001 | |

| n_stems | 0.43 | 0.001 | |

| land_cover | 0.41 | 0.002 | |

| landscape_porportion | 0.41 | 0.002 | |

| n_trees | 0.40 | 0.001 | |

| cult_500 | 0.40 | 0.001 | |

| mean_H | 0.39 | 0.001 | |

| greatest_patch | 0.38 | 0.003 | |

| largest_patch_index | 0.38 | 0.003 | |

| mean_patch | 0.38 | 0.001 | |

| age | 0.36 | 0.001 | |

| cattle_100 | 0.36 | 0.002 |

To verify the presence of spatial autocorrelation in our predictors and responses, we calculated a geographical distance matrix between study plots and performed Moran's I test for all calculated variables. We detected spatial autocorrelation for 24 predictors, but none in our response variables (i.e., diversity metrics).

Finally, partial redundancy analysis (pRDA) was performed in vegan, separately for tree and understory layer. To take into account spatial autocorrelation, we fitted a pRDA specifying “locality” as condition, to be able to rule out locality effect on the ordination. The “condition” argument thereby defines partial terms that are fitted before other constraints and can be used to remove the effects of background variables, and their contribution to decomposing inertia (variance) is reported separately (Oksanen et al., 2013). Additionally, we performed Hellinger transformation of our community data as recommended by Legendre and Gallagher (2001). We further selected predictors from the set obtained with the NMDS screening, by checking for correlation (r > 0.7), performing Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis (setting the threshold to 10), and then using the vegan ordistep function which performs automatic stepwise model building for constrained ordination methods (Oksanen et al., 2013).

2.12.2. General linearized models between main causes and facilitators of disturbance and main response variables

To select meaningful variables to fit our GLMs, we inspected the NMDS and pRDA graph and selected a set of uncorrelated response variables based on the direction of the arrows in the graphs. We then compiled a set of predictor variables that correlated with each selected response and checked for correlation within each set, removing one of the elements in pairs with r > 0.7. In parallel, we merged all predictor sets and removed highly correlated and spatially autocorrelated variables. Once a set of consensus predictors was obtained, we conducted a VIF analysis (setting the threshold to 10) and obtained a reduced set of primary and secondary predictors (Table 2). We thus reduced the pool of geo‐environmental variables to four, that of causes to four, and that of facilitators to seven. In addition, we selected response variables for level, including diversity metrics and indicators.

TABLE 2.

Retained predictors for GLMs building

| Predictors | Responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Geo‐environmental | Tree layer diversity | ||

| north | northness | TSR | tree species richness |

| slope | slope | TPielou | tree Pielou's evenness |

| mean_prec | mean annual precipitation | Tshann | tree Shannon's diversity |

| mean_T | mean annual temperature | TsesPD | tree standardized phylogenetic diversity |

| Causes | TsesMPDABU | abundance‐weighted trees standardized mean pairwise distance | |

| cult_50m | cultivated fields in 50 m buffer | TsesMNTDABU | abundance‐weighted trees standardized mean nearest taxon distance |

| cattle | presence of cattle | FDis | Functional Dispersion |

| logg | logging signs | Feve | Functional Evenness |

| protected | pretected status | FDiv | Functional Divergence |

| Facilitators | FRic | Functional Richness | |

| path_dist | distance from closest path | AGBplot | plot above‐ground biomass |

| house_dist | distance from closest house | Understory diversity | |

| track_dist | distance to closest track | HSR | understory species richness |

| edge | the plot is located at the edge of the fragment | Hpielou | understory Pielou's evenness |

| age | minimum age of the plot | Hshann | understory Shannon's diversity index |

| cattle_100 | presence of cattle in 100 m buffer | HsesPD | understory standardized phylogenetic diversity |

| median_patch | median forest patch size in 1 km buffer | HsesMPDABU | abundance‐weighted understory standardized mean pairwise distances |

| Indicators | HsesMNTDABU | abundance‐weighted understory standardized mean nearest taxon distances | |

| n_inv_sp_T | number of invasive species of trees | ||

| n_FST_sp_T | number of fast‐growing species of trees | ||

| n_FST_ind_T | number of fast‐growing species of trees individuals | ||

| %_n_CON_sp_T | % of species of trees associated with conserved forests | ||

| Level | |||

| n_large_trees | number of trees with DBH > 30 cm | ||

| n_stems | number of stems | ||

| n_trees | number of trees | ||

| n_sp > 10DBH | number of species with DBH > 10 cm | ||

| Tree layer diversity | |||

| FDiv | Functional divergence | ||

| FRic | Functional richness | ||

| FDis | Functional dispersion | ||

| FEve | Functional evenness | ||

| Tshann | Trees Shannon diversity index | ||

| TsesMPD | Trees standardized mean pair distance | ||

| TsesMPDABU | Abundance‐weighted trees standardized mean pairwise distance | ||

| TMNTDABU | Abundance‐weighted trees standardized mean nearest taxon distance | ||

| AGBplot | plot aboveground biomass |

Predictor categories refer to the groups of predictor variables categorized in (Appendix A2).

For each selected response, we identified the best conditional distribution and then performed automated selection of the optimal Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with the regsubsets function in the leaps package (Lumley & Lumley, 2013), unifying all groups of predictor variables. We specified a maximum number of predictors of four. Predictors were scaled, and a “log” link was specified in the family argument.

Thus, our GLMs related separately number of species (trees and understory), species diversity (Shannon and Pielou's indices for trees and understory), abundance‐weighted phylogenetic diversity and structure (trees sesPD, sesMPDABU, sesMNTDABU; understory sesPD, sesMPDABU, sesMNTDABU), functional diversity (FDiv, FRic, FEve, FDis), and aboveground biomass (AGBplot) as response variables with selected explanatory variables among each group of predictors (geo‐environmental causes and facilitators).

Second, we performed automated selection of the optimal GLMs with AGB, understory number of species, understory Shannon's and Pielou's indices, understory phylogenetic diversity and structure, as response variables and tree diversity indices, level and indicators of disturbance as sets of secondary predictor variables.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Plot‐based species inventory of tree and understory layers

3.1.1. Tree layer

We recorded 9,841 tree individuals belonging to 98 taxa. From these, 89 were identified to species level, six to genus, one to family, and two lianas remained unidentified due to lack of leaves, flowers, or fruits required for identification (see the Appendix A3 for the complete list of species and collected herbarium vouchers). Identified taxa belonged to 64 genera and 41 families. The only conifer recorded in the study area was Podocarpus oleifolia, and the only tree fern was Blechnum schomburgkii.

Asteraceae (14 species), Melastomataceae, Ericaceae, Primulaceae (with 6 species each), Lauraceae, and Rosaceae (5) were found to be the most diverse families in the study area. Miconia squamulosa (1,194 individuals) and Cavendishia bracteata (1,130) were the most abundant species across the study area, followed by Weinmannia tomentosa (805) and Daphnopsis caracasana (522).

3.1.2. Understory layer

Overall, 326 understory taxa were recorded, with 266 of them identified to species level, 59 to genus, and one to family level (Appendix A3). Identified taxa belonged to 174 genera and 82 families. Orchidaceae (41 species), Asteraceae (38), and Polypodiaceae (16) were the most diverse families, followed by Piperaceae (13), Bromeliaceae (12), Melastomataceae (11), Dryopteridaceae (10), Ericaceae (9), and Rosaceae (9). Dryopteridaceae, Orchidaceae, Poaceae, Blechnaceae, and Bromeliaceae were the most abundant families.

3.2. Plot‐based community ordination (NMDS, cluster analysis and Kruskal–Wallis test/ANOVA)

3.2.1. Tree layer

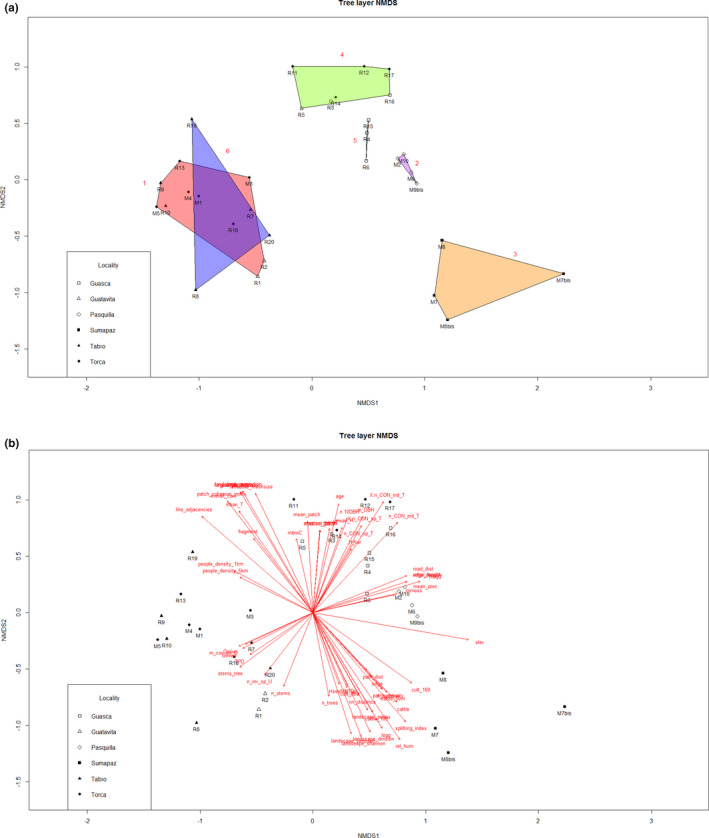

For the 3D ordination solution, we obtained a final stress value of 0.1160879 after 206 iterations. Visual interpretation of the NMDS graph led to the identification of three main groups. The subsequent cluster analysis revealed three additional groups, which showed deep divergence in the dendrogram (nodes at less than 50% remaining information), totaling six groups/clusters, which were used for the indicator species analysis (see Appendix A5 for further details on the indicator species analysis results).

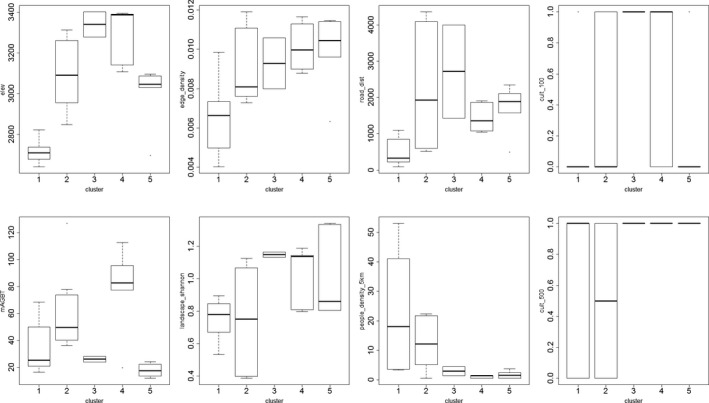

The NMDS graph (Appendix A6) showed numerous statistically significant axis correlations of environmental variables including elevation, relative humidity, and mean temperature, while the Kruskal–Wallis test and parametric ANOVA showed that floristic differences among all groups were related to elevation (chi‐sq = 25.94, p = .0009), mean temperature (chi‐sq = 20.99, p = .0008), relative humidity (chi‐sq = 25.71, p = .0001), presence of logging (chi‐sq = 17.57, p = .0035), presence of cattle (chi‐sq = 21.05, p = .0008), presence of cattle in a 50 m buffer (chi‐sq = 15.90, p = .0071), presence of cultivated fields in a 100 m buffer (chi‐sq = 23.94, p = .0002), Shannon's landscape diversity (F = 5.58, p = .0013), like adjacencies (chi‐sq = 18.37, p = .0025), distance to roads (chi‐sq = 19.45, p = .0016), and minimum age of the fragment (chi‐sq = 11.95, p = .0355).

The resulting NMDS graphs highlighted some interesting patterns. The NMDS graph of axis 1 versus 2 depicted the variables linked to aboveground biomass (AGB), percentage of late successional species, DBH, height and minimum age on the right hand side, opposite to the variables linked to the number of fast‐growing species of trees, mean exotic species cover in the understory, or to the number of trees and the number of stems in the plots (inverse correlation). In the same plot, the AGB showed high positive correlation with distances to roads, lichen cover in the canopy and mosses cover on the soil and inverse correlation with functional diversity, and Gini coefficient. Moreover, trees abundance‐weighted mean nearest taxon distance (TMNTDABU) lied opposite to the indicators of fragmentation. A complete table of NMDS variable correlation filtered through species abundance can be found in Appendix A7.

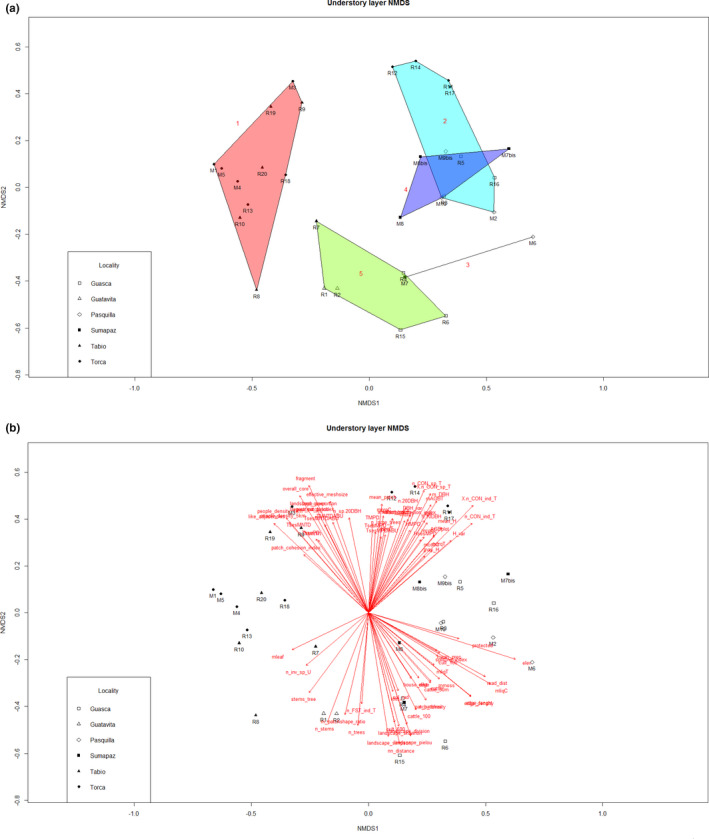

3.2.2. Understory layer

For the 3D ordination solution, we obtained a final stress value of 0.1514607 after 20 iterations. Visual grouping within the NMDS graph was not feasible (Appendix A8). The cluster analysis identified five main groups/clusters selecting nodes at less than 20% remaining information. Indicator species analysis did not clearly separate the plot localities from each other (Appendix A5).

Kruskal–Wallis test and parametric ANOVA showed that floristic differences among all groups were related to elevation (chi‐sq = 24.06, p = .0001), distance to roads (chi‐sq = 14.23, p = .0066), edge density (F = 4.93, p = .004), presence of cultivated fields in a 100 m buffer (chi‐sq = 23.93, p = .0002), mean tree AGB (chi‐sq = 13.69, p = .01774), Shannon's landscape diversity (F = 3.04, p = .0343), people density in a 5 km buffer (chi‐sq = 15.88, p = .0032), and presence of cultivated fields in a 500 m buffer (chi‐sq = 8.35, p = .0797).

In the understory, elevation again was the most correlated environmental variable with species abundances (see Appendix A7 for details on variables correlation with NMDS axis). In the NDMS graph of axis 1 versus 2, the indicators of fragmentation, together with the presence of cattle and cultivated fields in the vicinity, were located opposite to the indicators of continuous forest cover and most of trees diversity metrics. AGB correlated directly with number of late successional species and distance to paths and tracks, and inversely with the number of fast‐growing species of trees and exotic understory species. Most of understory diversity metrics pointed toward the lower part of the graphs, together with fragmentation indicators and exotic species cover in the understory, number of trees, stems, and fast‐growing species of trees. Understory phylogenetic mean pairwise distances were correlated with AGB.

3.3. pRDA

3.3.1. Tree layer

From the set of 25 variables with R sq > 0.35 (Table 1), after testing for redundancy, we limited our analysis to a subset of 10 variables: elevation, presence of logging, Shannon's landscape diversity, mean temperature, presence of cattle, presence of cultivated fields in a 100 m buffer, minimum fragment age, distance to roads, and presence of cattle in a 50 m buffer. The ordistep function selected seven of these: elevation, presence of logging, Shannon's landscape diversity, mean temperature, presence of cattle, minimum fragment age, and distance to roads.

The pRDA had an R sq of 0.23 and adjusted R sq of 0.17. The proportional conditional explained variance was 0.45, while the constrained explained variance was 0.24. The unconstrained explained variance was 0.31. Presence of cattle and lower distances to roads were associated with tree layer group 1 which was also positively correlated with Shannon's landscape diversity and negatively with elevation. Group 4 was defined by lower values of Shannon's landscape diversity and was positively correlated with minimum fragment age. Group 5 had some degree of negative correlation with minimum fragment age. Group 6 had an inverse correlation with elevation and minimum fragment age, and was associated with signs of logging, higher Shannon's landscape diversity, and absence of cattle. Groups 2 and 3 were not characterized by any particular association with the ordination variables (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

pRDA and Cluster analysis convex hulls of the tree layer. RDA graphs with convex hull volumes of tree layer groups for axis 1–2 (a), 2–3 (b), and 1–3 (c). (d) cluster dendrogram of plots species communities. Group 1 had Myrcianthes leucoxyla, Viburnum triphyllum, and Miconia elaeoides as statistically significant indicator species and comprised plots from Torca, Tabio, and Guatavita. Group 2 was characterized by Monticalia pulchella, Macleania rupestris, and Ilex kunthiana, and comprised plots exclusively from Pasquilla. Group 3 had Gaultheria anastomosans, Ageratina glyptophlebia, Buquetia glutinosa, Ageratina boyacensis, Berberis glauca, and Vaccinium floribundum as statistically significant indicator species, and comprised exclusively plots form Sumapaz. Group 4 was characterized by Myrsine coriacea and Clusia multiflora and included plots from Torca and Guasca. Group 5 included Cavendishia bracteata, Diplostephium rosmarinifolium, Gaiadendron punctatum, and Ulex europaeus, and comprised only plots from Guasca. Group 6 had Varronia cylindrostachia and Myrsine guianensis and included plots from Tabio and from Torca. For detailed IVI values and relative p‐values refer to the Appendix A5

3.3.2. Understory layer

From the set of 38 variables with R sq > 0.35 (Table 1), after the assessment of redundancy, we limited our analysis to a subset of 10: elevation, number of trees, edge density, Shannon's landscape diversity, mean tree aboveground biomass (mAGBT), presence of cultivated fields in a 500 m buffer, minimum fragment age, distance to roads, people density in a 5 km buffer, and fragment size. The ordistep function selected seven of these: elevation, edge density, Shannon's landscape diversity, mAGBT, presence of cultivated fields in a 500 m buffer, distance to roads, and people density in a 5 km buffer.

The pRDA had an R sq of 0.26 and adjusted R sq of 0.11. The proportional conditional explained variance was 0.29, while the constrained explained variance was 0.26. The unconstrained was 0.45.

The results of the pRDA indicated that group 1 was characterized by higher values of Shannon's landscape diversity, lower values for distance from roads, lower elevation, and lower edge density. In contrast with that, group 2 was linked with higher values for distance from roads, higher elevation, lower Shannon's landscape diversity, absence of cultivated fields in a 500 m buffer, and lower population density. Group 3 had lower values of mean tree biomass and higher values of population density. Group 5 was associated with lower values of mean tree biomass. Group 4 was not characterized by any particular association with the ordination variables (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

pRDA and Cluster analysis convex hulls of the understory. RDA graphs with convex hull volumes of understory groups for axis 1–2 (a), 2–3 (b), and 1–3 (c). (d) cluster dendrogram of plots species communities. The first group had Oreopanax incisus and Passiflora bogotensis as indicator species (Appendix A5) and included plots from Torca and Tabio. The second group had Elaphoglossum lingua as indicator species, including plots form Pasquilla, Guasca, and Torca. The third group had Monnina aestuans, Peperomia rotundata, and Nertera granadensis among higher valued indicator species. It included only two plots, one from Sumapaz and one from Pasquilla. The fourth group had Greigia stenolepis and Rubus acanthophyllos among indicator species and comprised plots from Sumapaz and Guasca. The last group had Ageratina asclepiadea as indicator species and comprised plots from Guatavita, Guasca, and Tabio. For detailed IVI values and relative p‐values refer to the Appendix A5

3.4. Generalized linear models

A total of 15 primary predictors, 17 secondary predictors, and 17 responses were retained for GLM building (Table 2). Significant variables in GLMs with either a good fit (McFadden R sq > 0.2) or a high Nagelkerke value (variance explained > 0.50) are reported below (Tables 3, 4 and 5). A complete table of all fitted GLMs is provided in Table S1. None of the variables associated with epiphytes cover was retained through the variable selection process and analysis.

TABLE 3.

GLMs of predictors versus responses, showing only GLMs with a good fit

| Response | Best model | Variable | Coefficients | Pseudo R 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | t value | p value (>|t|) | McFadden | Nagelkerke | |||

| Tshann | Tshann ~ slope+mean_T + house_dist+cult_50m | (Intercept) | 0.70361 | 0.02540 | 27.699 | <2e−16 | 0.752990 | 0.814632 |

| slope | −0.08664 | 0.02698 | −3.211 | .0034 | ||||

| mean_T | −0.02686 | 0.02873 | −0.935 | .3580 | ||||

| house_dist | −0.04705 | 0.02583 | −1.822 | .0796 | ||||

| cult_50m | −0.04004 | 0.02870 | −1.395 | .1744 | ||||

| Hshann | Hshann ~ track_dist+mean_prec + age+house_dist | (Intercept) | 0.89579 | 0.02215 | 40.441 | <2e−16 | 0.669964 | 0.759986 |

| track_dist | 0.06937 | 0.02916 | 2.379 | .024680 | ||||

| mean_prec | 0.08776 | 0.02867 | 3.061 | .004944 | ||||

| age | −0.10445 | 0.02380 | −4.389 | .000157 | ||||

| house_dist | −0.03438 | 0.02257 | −1.523 | .139413 | ||||

| AGB | AGBplot ~ slope+age + cattle+cult_50m | (Intercept) | 1.7145 | 0.07224 | 23.734 | <2e−16 | 0.150415 | 0.525516 |

| slope | −0.17248 | 0.07773 | −2.219 | .035092 | ||||

| age | 0.31665 | 0.07803 | 4.058 | .000379 | ||||

| cattle | 0.23182 | 0.09783 | 2.370 | .025207 | ||||

| cult_50m | −0.23070 | 0.09631 | −2.395 | .023807 | ||||

Predictor categories refer to the groups of predictor variables categorized in the Appendix A2.

TABLE 4.

GLMs of secondary predictors versus responses, showing only GLMs with a good fit

| Response | Best model | Variable | Coefficients | Pseudo R 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | t value | p value (>|t|) | McFadden | Nagelkerke | |||

| Hshann | Hshann ~ FDis+FRic + n_stems+n_inv_sp_T | (Intercept) | 0.89802 | 0.02507 | 35.825 | <2e−16 | 0.370602 | 0.474078 |

| FDis | −0.07597 | 0.03485 | −2.180 | .0382 | ||||

| FRic | 0.07827 | 0.03082 | 2.540 | .0172 | ||||

| n_stems | 0.03100 | 0.02455 | 1.262 | .2176 | ||||

| n_inv_sp_T | −0.04740 | 0.02916 | −1.626 | .1156 | ||||

| HsesMPDABU | HsesMPDABU ~ FDiv+FRic + n_sp.10DBH + TsesMPDABU | (Intercept) | 0.82655 | 0.07123 | 11.605 | 5.32e−12 | 0.261149 | 0.581732 |

| FDiv | 0.24527 | 0.08248 | 2.974 | .00613 | ||||

| FRic | −0.26250 | 0.08501 | −3.088 | .00463 | ||||

| n_sp.10DBH | 0.12922 | 0.07900 | 1.636 | .11351 | ||||

| TsesMPDABU | 0.15706 | 0.05962 | 2.634 | .01380 | ||||

| AGB | AGBplot ~ TsesMPD+n_large_trees + n_trees+%n_CON_sp_T | (Intercept) | 1.7140 | 0.07467 | 22.955 | <2e−16 | 0.151863 | 0.528924 |

| TsesMPD | −0.06882 | 0.11824 | −0.582 | .56535 | ||||

| n_large_trees | 0.36350 | 0.11200 | 3.246 | .00312 | ||||

| n_trees | 0.22454 | 0.10409 | 2.157 | .04005 | ||||

| %n_CON_sp_T | 0.29929 | 0.11420 | 2.621 | .01423 | ||||

Predictor categories refer to the groups of predictor variables categorized in the Appendix A2.

TABLE 5.

GLMs variables relationships: + indicates a positive relationship and − indicates a negative relationship. Higlighted cells represent GLMs with a good fit

| TSR | Tshann | Tpielou | TsesPD | TsesMPDABU | TsesMNTDABU | HSR | Hshann | Hpielou | HsesPD | HsesMNTDABU | HsesMPDABU | FDis | FDiv | FEve | FRic | AGB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean_T | − | − | − | ||||||||||||||

| mean_prec | + | ||||||||||||||||

| north | + | ||||||||||||||||

| slope | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||||||||

| logg | − | + | − | ||||||||||||||

| cattle | + | ||||||||||||||||

| cult_50m | − | − | + | − | |||||||||||||

| protected | − | − | |||||||||||||||

| edge | − | − | + | + | − | − | |||||||||||

| house_dist | − | ||||||||||||||||

| cattle_100 | − | − | + | ||||||||||||||

| median_patch | − | ||||||||||||||||

| age | − | − | + | ||||||||||||||

| track_dist | + | − | |||||||||||||||

| n.sp_10DBH | + | ||||||||||||||||

| n_trees | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| n_large_trees | + | ||||||||||||||||

| %n_CON_sp_T | + | ||||||||||||||||

| n_FST_ind_T | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| n_stems | + | ||||||||||||||||

| FDiv | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| FRic | + | + | − | − | |||||||||||||

| FDis | − | − | |||||||||||||||

| TsesMPDABU | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| TsesMPD | + |

Tree layer Shannon's diversity decreased with slope. Understory Shannon's diversity increased with distance to tracks, mean precipitation, and tree layer functional richness (FRic), but decreased with minimum age and functional dispersion (FDis). Understory abundance‐weighted phylogenetic mean pairwise distances (HsesMPDABU) increased with functional divergence (FDiv) and tree layer abundance‐weighted phylogenetic mean pairwise distances (TsesMPDABU) and decreased with FRic. Aboveground biomass (AGB) increased with increasing minimum age of the plot and presence of cattle within the plot, and decreased with slope and proximity of cultivated fields. AGB also increased with the number of trees and large trees and with the proportion of late successional species of tree.

3.4.1. Other general trends (from models without a good fit)

Among environmental predictors, slope had a negative effect on FDis, FRic, HsesMPDABU, tree layer species richness (TSR), tree layer Pielou's evenness (Tpielou), tree layer abundance‐weighted mean phylogenetic nearest neighbor distance (TsesMNTDABU). Mean temperature had a negative effect on understory phylogenetic diversity (HsesPD) and Tpielou. Northness had a positive effect on TSR. Among the causes predictors, logging had negative effect on functional evenness (FEve) and TSR, and a positive effect on understory layer Pielou's evenness (Hpielou). The presence of cultivated fields in the immediate surrounding of plots (50 m) had a negative effect on HSR and TsesMNTDABU and a positive effect on understory abundance‐weighted mean phylogenetic nearest neighbor distance (HsesMNTDABU). Protection status had a negative effect on HsesMNTDABU and tree layer phylogenetic diversity (TsesPD). As to the facilitators, the edge effect was linked with higher values of FDis and HsesMPDABU, and lower values of HsesMNTDABU, HsesPD, FDiv, and FRic. Increasing distance from houses had a negative effect on TSR, while increasing distance from tracks had negative effect on HsesPD. The presence of cattle in a 100 m buffer was linked to higher values of HsesMNTDABU, and lower values of tree layer abundance‐weighted mean phylogenetic pairwise distance (TsesMPDABU) and TsesMNTDABU. Median patch size had negative effect on HSR. Increasing minimum fragment age had a negative effect on HPielou. Coming to the secondary predictors, the number of species with DBH > 10 cm and the number of trees had positive effect on HsesMNTDABU. The number of fast‐growing trees species individuals had a positive effect on HsesMNTDABU and HsesPD. The number of stems had a positive effect on Hpielou. FDiv had a positive effect on HSR. FRic had negative effect on HsesMNTDABU and positive on HsesPD. FDis had a negative effect on HsesPD. Finally, TsesMPDABU had positive effect on HsesPD and TsesMPD had positive effect on Hpielou.

4. DISCUSSION

Pressure of urbanization on natural environments and its consequences has been the subject of numerous studies. However, high Andean forests (bosques altoandinos) have rarely been investigated in this context. Our study is the first to analyze the role of multiple factors in shaping environmental impact on these forests through urbanization and associated factors in the metropolitan area of Bogotá. However, we are aware of the limitations of this research, which is of rather explorative character and based on data from an area of in total 1.28 ha only. Our sampling design reflects the hurdles of working in a mixed urban–rural matrix, mostly privately owned. Also, having a limited number of plots, we decided to put a stronger emphasis on the variables filtering, to drastically reduce the number of tested hypotheses. Nevertheless, the studied forest fragments belong to several of the localities harboring the highest forest cover within the Capital District and we find the types of high Andean forests covered here to be representative for the hinterland of Bogotá.

Using the composition of natural vegetation as a benchmark, our study plots were dominated by Melastomataceae, Ericaceae, and Asteraceae in the tree layer, which is in accordance with previous work (Cuatrecasas, 1934, 1958; Franco et al., 2010; Torres & Marina, 2016). Bromeliaceae and Orchidaceae were the most diverse families in the understory, coinciding with reports by Cuatrecasas (1934, 1958) and Rangel et al. (2008). Notably, with the exception of Rangel et al. (2008), no recent inventories of the understory were undertaken in the target area prior to this study. The fact that many epiphytic species were found terrestrial in the understory may be due to certain favorable environmental conditions, such as low incidence of light, high humidity, and lower influence of wind than in the canopy (Krömer et al., 2007).

Overall tree species richness of the total area assessed (98) was similar to the 90 taxa reported by Rodríguez‐Alarcón et al. (2018) for an ecologically similar study area near Bogotá. Van der Hammen (1998) reported 50–60 species for 500 m2 plots of high Andean forest in the watershed of the Rio Bogotá, 20–30 of which belonged to trees and shrubs. Our own tree species count ranged between 10 and 24, with an average of 16, per 400 m2 plot, and Shannon's tree diversity varied between 1.05 and 2.6. Overall, these figures also compare well to those reported for high Andean forest ecosystems (2,300–2,900 m) in Southern Ecuador by Cabrera et al. (2019), who used a higher DBH threshold (10 cm) and obtained about 21 tree species and an average value of 2.44 for Shannon's diversity.

Thus far, only few published studies exist for the target area that aimed at characterizing the various communities of bosques altoandinos in terms of species composition. Using a phytosociological approach, Cortés et al. (1999) and Cortés (2008) described the Myrcianthes leucoxyla‐Miconia squamulosa community for the internal slopes of the Rio Bogotá watershed, characterized by scarce humidity and low precipitation, with high abundance of Oreopanax incisus and conspicuous lianas in the understory. This community corresponds to our tree clusters 1 and 6 and understory clusters 1 and 5. The pRDA further revealed a lower elevation, higher Shannon's landscape diversity, lower minimum fragment age, presence of logging and lower distance to roads as characteristic for this community, supporting the notion that it represents secondary forest, probably developing on patches of abandoned agricultural areas on the slopes surrounding cultivated and farmed plains (Cortés, 2008). Understory cluster 5 was generally found at medium elevations, on small high plains, with a drier climate (Cortés, 2008; Cortés et al., 1999), and in forest patches with generally low values of aboveground biomass.

The Drimys granadensis‐Weinmannia tomentosa community is a second bosque altoandino subtype (Vargas & Zuluaga, 1980), corresponding to our tree clusters 2 and 4. Cluster 2 is similar to the Criotoniopsis bogotana‐Weinmannia tomentosa forest subtypes described for elevations between 3,100 and 3,300 m (Cortés, 2008), whereas cluster 4 is found at the slopes and peaks of the watershed of the Río Bogotá between 2,700 and 3,200 m (Cortés, 2008). According to Cortés (2008) and Luteyn (2002), the presence of Macleania rupestris in the lower canopy of these communities points toward recent human intervention. This association is known to prefer humid, cold climates and steep grounds; according to our field observations, it is also associated with high lichen and moss cover in the canopy, which prosper in such a relatively high humidity (Batke et al., 2015; Munzi et al., 2014; Wolf, 1993). As shown in the pRDA ordination, it is also linked to low Shannon's landscape diversity, and higher minimum fragment age, probably representing secondary forest fragments approaching the structure of natural forest communities.

Our tree clusters 3 and 5 did not correspond to previously described communities. Cluster 3 was restricted to bosques altoandinos near Sumapaz, the largest known paramo on Earth. Characteristic elements of this cluster are families of high elevations such as Asteraceae and Ericaceae (Bach et al., 2007; Cuatrecasas, 1958; Sturm & Rangel, 1985), also typically found in areas subjected to fires or selective logging (Cuatrecasas, 1958). The latter notion is supported by the observed presence of both cattle and cultivated fields in the immediate surrounding, by a high Shannon's landscape diversity, and by the presence of logging, indicating recent and ongoing intervention in the area. Nonetheless, full‐grown individuals of Weinmannia fagaroides and Polylepis quadrijuga were found in two of the plots of this cluster, together with some young individuals of Podocarpus oleifolia and Berberis glauca abundant in the lower canopy, and a dense cover of mosses and ferns, which suggests that some small “islands” of mature forest elements were able to persist within the disturbed, secondary forest matrix. Understory cluster 3 did not fit any previously described communities either, but the indicator species of this cluster are known to be either dispersed by birds, for example, Monnina aestuans (Romero, 2002) and Nertera granadensis (Vargas‐Ríos, 1997), or by small mammals or birds, for example, in the case of the sticky fruits of Peperomia (Frenzke et al., 2016). Possibly, this cluster represents a successional understory community mainly dispersed by animals, which prosper in previously disturbed areas, as suggested by the high people density within 5 km radius and relatively low mean tree biomass. Tree cluster 5 was found in the Guasca region only and exhibits features of a disturbed, gap‐filled forest (azonal páramo) including the presence of invasive Ulex europaeus, which is confirmed by the pRDA correlation with lower minimum fragment age values. Another common species, Cavendishia bracteata, has been associated with secondary growth (Cortés, 2008). This cluster had rather low like adjacencies values and average Shannon's landscape diversity and distances to roads, which point to a somehow continued disturbance regime in the past. Indeed, this area, up to the 1990s, used to be an open‐pit limestone mine (Pèrez Sanz de Santamaría, 2013).

Notably, tree and understory communities found in the same plots did not always correspond to the same community's type, which suggests that different types of intervention act differentially on the tree and understory layers. For instance, cattle grazing, erosion, and expansion of edge species will affect the understory at a different pace than the tree layer (Halpern & Lutz, 2013; Millspaugh & Thompson, 2011; Thrippleton et al., 2016).

Our findings support the notion that bosques altoandinos in the vicinity of Bogotá are floristically and structurally not homogeneous, resulting in overall high species diversity, especially in the understory, with each of the study sites and plots contributing a portion to this diversity (i.e., high beta diversity). The observed differences in species composition between the study sites, and the high proportion of pRDA‐explained variance that was linked to the “locality” condition, may be determined by topographic variation, which promotes changes in structure, composition, and dynamics of the vegetation, even at small scales in high Andean ecosystems (Homeier et al., 2010; López & Duque, 2010). Our results are similar to a recent study that found substantial differences in species composition between municipalities in the region (Hurtado‐Martilletti et al., 2020), pointing toward the importance of landscape and habitat heterogeneity as a relevant criterion when assessing the impact of urbanization, since each locality may contribute unique elements of diversity not present at other localities, even within close distances. Following up on our first research question, taken aside the effects of local homogenization processes, our data show that plant communities in bosques altoandinos are mainly driven by a limited suite of geo‐environmental and disturbance factors, namely: elevation, mean temperature and relative humidity on one hand, and by the presence of cultivated fields and cattle in the immediate sourroundings of the plots, population density, Shannon's landscape diversity, and forest edge density on the other.

The compositionally based clustering of tree and understory communities was largely correlated with both geo‐environmental and disturbance variables, namely, elevation, people density, Shannon's landscape diversity and distance to roads. Mean temperature, relative humidity, logging, and minimum plot age were important factors driving tree species composition, but not the composition of understory species. For the latter, additional variables associated with edge effects, such as the proximity to cultivated fields, edge density, and distance from main roads were relevant. Additionally, mean tree aboveground biomass was a determinant factor in shaping the understory community. These results support the notion of a higher sensitivity of the understory to fragmentation and habitat heterogeneity (Forman & Alexander, 1998; Tyser & Worley, 1992).

Our results show effects of both geo‐environmental parameters and disturbance‐related variables as predictors of both community structure and diversity. Among the geo‐environmental parameters, the negative effects of the increase in slope on tree and understory diversity and aboveground biomass were evident. Slope is related to soil erosion, water drainage, and other unfavorable growth conditions which may act as environmental filters, reducing the number of taxa that can cope with them effectively and may also limit aboveground productivity. Higher mean temperatures were linked to lower tree Pielou's evenness and Understory phylogenetic diversity. This fact could be linked to the higher density of human activities at milder temperatures/lower parts of our study area, which are associated with highly disturbed forest communities, mostly dominated by species as Miconia squamulosa or Cavendishia bracteata, and host poorer understory communities. Higher precipitation values were linked to higher understory Shannon's diversity, possibly due to increased soil nutrients and moisture and thus by the absence of an environmental filter related to water availability.

With regard to human disturbance predictors, many of the previously identified relevant variables in literature were also selected through our multi‐step analysis, such as minimum age of the forest fragment, distance to houses, edge effect, and presence or proximity of cattle and cultivated fields. People density, on the other hand, showed to be too spatially autocorrelated to be used in our GLMs. Also, among all calculated forest fragmentation metrics, the only one which was selected was (median) forest patch size, already reported to be relevant for plant diversity as an indirect measure of habitat loss in the review of Fahrig (2003). As to the selected responses, tree layer diversity metrics were not particularly sensitive, retrieving only one GLM with a good fit. The correlation between higher distance from houses and forest protection status with lower tree species richness and low phylogenetic diversity was not immediately intuitive, but could be a sign of the deliberate introduction of useful tree species in the vicinity of rural houses, to be harvested for wood or other uses, or of the lack of edge‐related tree species in the interior of protected forest fragments. However, the presence of cattle and cultivated fields in the immediate proximity of plots leading to tree phylogenetic clustering, but on the other hand to understory phylogenetic dispersion, illustrates the disrupting, multi‐layer impact of landscape‐level patchiness and human activities.

Disturbed forests tend to exhibit functional and phylogenetical clustering due to the elimination of entire lineages sensible to disturbance, an effect known as environmental filtering (Chun & Lee, 2018; Gerhold et al., 2015; Kusuma et al., 2018; Mouchet et al., 2010; Ribeiro et al., 2016). Phylogenetic dispersion is expected to be higher in undisturbed, more mature forests than in early successional forests, due to competitive exclusion (Ding et al., 2012; Letcher, 2009; Norden et al., 2012; Purschke et al., 2013). In our study, local, chronic disturbances, such as proximity to farming activities or the presence of cattle in the immediate surroundings, had indeed a negative effect on tree phylogenetic diversity and resulted in phylogenetic clustering, supporting findings by Ribeiro et al. (2015, 2016). Likely, the floristic drift associated with this type of disturbance results in the co‐occurrence of more closely related taxa by decreasing effects of competitive exclusion. On the other hand, the observed increase of phylogenetic dispersion in the understory in close proximity of cattle or cultivated fields may be the result of opportunistic pioneer or exotic species, which introduce different lineages from those associated with more mature forest fragments (Hill & Curran, 2001; Kupfer et al., 2004).

Identified understory diversity metrics with the highest sensitivity to human disturbance were Shannon's diversity and phylogenetic clustering. As suggested by Forman and Alexander (1998) and Tyser and Worley (1992), the number and diversity of understory species were positively related to disturbance‐related variables. Proximity to human activities such as farming and the more recent establishment of forest patches (lower minimum age) fosters generalists or fast‐growing, nutrient‐, and light‐demanding species (Marcantonio et al., 2013). However, at the same time the edge effect promotes less phylogenetic diversity of the understory vegetation, which is in accordance with Ribeiro et al. (2016). This could be explained, in our case, by the fact that ferns and other early diverging taxa diversity tends to diminish toward the edge of a forest fragment to leave place to generalists and agricultural weeds, which can cope better with the site conditions. Larger median forest fragments size also resulted in less understory species, suggesting that recruitment of edge‐related species increment the number of species in smaller forest patches.

The observation that increasing tree functional divergence, and tree phylogenetic dispersion were linked to higher understory phylogenetic dispersion, may indicate that higher trait diversity in the upper stratum allows for more species to colonize the understory. This is partially supported through similar findings by Ampoorter et al. (2014) and Evy et al. (2016), who reported that a multi‐tree species mixture may induce a higher number of understory species, for instance, by modifying environmental conditions relevant to herbaceous plants and seedlings (Vockenhuber et al., 2011). At the same time, functional richness and functional dispersion showed contrasting effects on understory metrics, underlining the multifaceted effect of the multidimensional functional diversity indices. Moreover, the number of trees, large trees, fast‐growing tree individuals, and stems were related to higher understory phylogenetic diversity and dispersion, and to understory Pielou's evenness, confirming that intrastand heterogeneity allows for different understory taxa to thrive due to differences in nutrients, light and water availability (Huebner et al., 1995).

Averaging 149 Mg/ha, the obtained values for aboveground biomass are within the figures reported from other high Andean forest fragments, ranging between 130 and 165 Mg/ha and in some cases up to 640 Mg/ha (Álvarez‐Dávila et al., 2017; Girardin et al., 2014; Rodríguez‐Alarcón et al., 2018). The relatively low mean values obtained here are probably explained by the inclusion of areas characterized by early regeneration stages in several plots. However, our results are higher than those of Moser et al. (2011), who reported 112 Mg/ha for forest plots within a similar elevation range. In regard to our models, AGB seemed to decrease at higher values of slope, which in our study area may relate to eroded soils and drier conditions, supporting a trend that has been reported for relatively moist forests in the Americas (Keith et al., 2009; Stegen et al., 2011), which is perhaps related to the lower soil water content available to sustain photosynthesis (Parton et al., 2012; Stegen et al., 2011), but that can also be a secondary effect of the different rate of agricultural exploitation or forest clearing history between lower and drier and higher and wetter soils in the study area in recent times (Etter et al., 2008; Etter & van Wyngaarden, 2000). Notably, low AGB was linked to the proximity of cultivated fields, suggesting a clear correlation between intervention causing patchy landscapes and lower biomass accumulation. However, the presence of cattle within the plot was linked to higher AGB values. This may be particular to our study area, in which we observed forest fragments with large trees but a much depauperate understory, located in proximity to farms. This is alarming as grazing may interfere with tree species recruitment and stamping may lead to higher soil erosion which in turn will reduce productivity over time in these last standing carbon stock fragments (Nepstad et al., 2002).

The positive correlation that AGB exhibits with the minimum fragment age, and number of trees and large trees, summed to a positive correlation with the percentage of late successional tree species, suggests that AGB is positively influenced by the abundance of slow‐growing species that stock large amount of carbon (Aldana et al., 2017; Álvarez‐Dávila et al., 2017). This finding relates to the question of biomass storage in forest plantations or tree monocultures. Conversely, the increment of environmental stressors in highly fragmented landscapes can increase the mortality of large trees (D'Angelo et al., 2004; Laurance et al., 2000). This promotes the uncontrolled growth of fast‐growing species with lower wood density, which reduces AGB (Berenguer et al., 2014; Chaplin‐Kramer et al., 2015; Laurance & Bierregaard, 1997; de Paula et al., 2011).

In conclusion, the increase of disturbance resulted overall in a negative effect on tree phylogenetic diversity and dispersion. Notably, disturbance affected aboveground biomass negatively. As to the understory, disturbance was associated with more diversity and more phylogenetic dispersion. The causes and the facilitators category variables were quite efficient in predicting diversity or AGB, among which edge effect, proximity of cattle and cultivated fields, and minimum fragment age appear to be the most important ones.

The plurality of diversity metrics can be difficult to interpret in the light of human disturbance. However, AGB proved to be sensitive to human disturbance and was closely related with the proportion of late successional species. Such indicators could serve as immediate proxies of human disturbance, rather than diversity measures themselves, which have also been shown to react ambiguously to the effects of fragmentation (Fahrig, 2003).

5. CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our study on taxonomic, phylogenetic, functional diversity and ABG of high Andean forest underscores the complexity and singularity of interactions between disturbance drivers and plant communities. The main goal of our approach was to test and quantify the alteration of high Andean forest composition, structure, and functioning through human disturbance, testing the effectiveness of known relevant drivers and indicators when a large number of variables are considered simultaneously. We contributed to the characterization of high Andean patterns of tree and understory diversity and local and regional human disturbance, which is usually considered to have a negative effect on native biodiversity and carbon storage. In our case, this fact was confirmed by lower tree layer diversity and a lower ABG in relation to increasing human disturbance, but was however not always apparent through the score of all the diversity metrics that we employed. Decline of AGB and disappearance of the forest ecosystem's late successional species is a warning signal that should impulse protection efforts and restoration measures. Yet, it is also true that the study area has now undergone anthropic disturbance over centuries, with continuous agropastoral activities and subsequent land cover change. In the context of the recovery of forest cover and ecosystem services, then our findings could be interpreted as a positive sign of resilience at a regional scale. Relatively small isolated fragments of high Andean forests can still host high plant diversity and serve as stepping stones or temporary refuges for the local fauna within the rural modified matrix. In this sense, efforts to implement forest connectivity and corridors and to guarantee land‐use continuity even in partially forested areas are priorities that should be taken into account by local decision‐makers. Successful conservation strategies require a sound understanding of community and ecosystem dynamics, and we hope that with the predictors and indicators of disturbance that we pointed out, it will be possible to improve the management strategies for the passive or active restoration and protection of the remaining forest fragments in the study area.

Our results contribute to urgently needed but yet missing baseline knowledge on main drivers of disturbance and its effects on the biodiversity in the study area. However, we strongly recommend that future studies should expand further the established plot network and that more investigations test our results on similar ecosystems to further disentangle the relationship between natural and human‐induced causes of diversity loss and their underlying mechanisms. As shown here, a first approximation can be achieved through an exploratory approach like the one that we employed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mariasole Calbi: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (lead); writing–original draft (lead); writing–review and editing (lead). Francisco Fajardo‐Gutiérrez: Data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing–original draft (supporting); writing–review and editing (supporting). Juan Manuel Posada: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); investigation (supporting); methodology (lead); project administration (equal); resources (equal); visualization (equal); writing–original draft (supporting); writing–review and editing (supporting). Robert Lücking: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (supporting); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (lead); supervision (equal); writing–original draft (equal); writing–review and editing (equal). Grischa Brokamp: Funding acquisition (equal); methodology (supporting); project administration (lead); resources (equal); supervision (equal); writing–original draft (equal); writing–review and editing (supporting). Thomas Borsch: Conceptualization (supporting); funding acquisition (lead); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); resources (equal); supervision (lead); writing–original draft (equal); writing–review and editing (supporting).

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS