Abstract

Rotator cuff tendon tears and tendinopathies are common injuries affecting a large portion of the population and can result in pain and joint dysfunction. Incidence of rotator cuff tears significantly increases with advancing age, and up to 90% of these tears involve the supraspinatus. Previous literature has shown that aging can lead to inferior mechanics, altered composition, and changes in structural properties of the supraspinatus. However, there is little known about changes in supraspinatus mechanical properties in context of other rotator cuff tendons. Alterations in tendon mechanical properties may indicate damage and an increased risk of rupture, and thus, the purpose of this study was to use a rat model to define age-related alterations in rotator cuff tendon mechanics to determine why the supraspinatus is more susceptible to tears due to aging than the infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor. Fatigue, viscoelastic, and quasi-static properties were evaluated in juvenile, adult, aged, and geriatric rats. Aging ubiquitously and adversely affected all rotator cuff tendons tested, particularly leading to increased stiffness, decreased stress relaxation, and decreased fatigue secant and tangent moduli in geriatric animals, suggesting a common intrinsic mechanism due to aging in all rotator cuff tendons. This study demonstrates that aging has a significant effect on rotator cuff tendon mechanical properties, though the supraspinatus was not preferentially affected. Thus, we are unable to attribute the aging-associated increase in supraspinatus tears to its mechanical response alone.

Keywords: Tendon, Aging, Tendon Biomechanics, Viscoelasticity, Fatigue, Quasi-static

INTRODUCTION

Rotator cuff tendon tears are a common, debilitating injury affecting a large portion of the population (Edelstein, Thomas, & Soslowsky, 2011). The rotator cuff is comprised of four major tendons, the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and the teres minor. When functioning properly, these tendons provide strength and stability to the glenohumeral joint. Rotator cuff tendon tears and tendinopathies are common injuries affecting a large portion of the population and can result in pain and joint dysfunction (Dang & Davies 2018). Incidence of rotator cuff tears significantly increases with age, with some studies claiming up to 50% of the general population experiencing a cuff tear by age 70 (Minagawa, et al., 2013). Of these rotator cuff tears, 90% involve injury to the supraspinatus tendon, 35% to the infraspinatus, and 25% to the subscapularis (Kempf, et al., 1999; Minagawa, et al., 2013; Muto, Inui, Ninomiya, Tanaka, & Nobuhara, 2017).

The effect of aging on supraspinatus tendon has been studied, but not in context of the other rotator cuff tendons. In human cadaveric supraspinatus tendons from asymptomatic shoulders, tensile strength is greater in specimens with mean age of 32.5 years, compared to specimens with mean age of 60.9 years (Nakajima, Rokuuma, Hamada, Tomatsu, & Fukuda, 1994), and in 90-day, 300-day, and 570-day old mouse supraspinatus tendons, changes in collagen initial alignment and fiber re-alignment suggest a decreased response to load with aging (Connizzo, Sarver, Iozzo, Birk, & Soslowsky, 2013). Accumulation of advanced glycation end-products, increased collagen cross-linking, and fatty infiltration increase in rat supraspinatus tendons between 24-months and 36-months of age(Gumucio J. , et al., 2014), which have separately been shown to cause alterations in rabbit tendon mechanical properties (Reddy, 2004; Steplewski, et al., 2017). However, none of these studies attempted to compare the supraspinatus to the other rotator cuff tendons. Other literature that does make comparisons across tendons and age are limited. Ultrasonographic evaluation of rotator cuff tendons in healthy patients between 20 and 84 years old showed a significant correlation between age and supraspinatus tendon thickness, and another between age and echogenicity, which is indicative of structural changes in tendon fiber alignment and tissue density, while the infraspinatus had only a trending correlation between age and these parameters, and none were found in the subscapularis (Yu, et al., 2012). However, age dependent alterations in tendon mechanical properties that may predispose the supraspinatus to injury relative to the other rotator cuff tendons remain unclear.

Changes in mechanical properties may indicate damage to the tendon and an increased risk of rupture; however, experiments investigating the effect of aging on tendon mechanics are inconclusive (Sharma & Maffulli, 2006; Miller, Thunes, Spandan, Musahl, & Debski, 2018). Some evidence suggests that tendon ultimate load, modulus, and strength decrease with age (Vogel, 1983), but others have shown that strength and stiffness increase with age (Shadwick, 1990; Nielsen, Skalicky, & Viidik, 1998). While strength and stiffness are distinguishing features of tendons, viscoelastic behaviors are important at physiological strains (LaCroix, et al., 2013). Changes in tendon viscoelasticity are detrimental to the tissue’s adaptation to load over time, and ability to store, translate, and dissipate energy (Sharma & Maffulli, 2006). In vivo observations of tendons in the elderly and young populations have shown that tendon stress relaxation and hysteresis are impacted by aging (Maganaris, 2001; Connizzo, Sarver, Iozzo, Birk, & Soslowsky, 2013), while others suggest that aging has no effect on tendon viscoelasticity (Flahiff, Brooks, Hollis, Schilden, & Nicolas, 1995; Jognson, et al., 1994). In addition to viscoelasticity, fatigue mechanics have also been studied. Progressive degradation of mechanical properties from cyclic (fatigue) loading contributes to tendon degeneration and susceptibility to rupture (Fung, et al., 2010; Soslowsky, et al., 2000). A rat study of aging Achilles tendon mechanical properties showed significant decreases in dynamic and secant modulus in fatigue loading with advancing age (Pardes, et al., 2017). A comprehensive assessment of rotator cuff tendon mechanics could clarify these contradictory effects of aging.

This rat model has been used previously to describe age related changes in rotator cuff muscle (Swan, Sato, Galatz, Thomopoulos, & Ward, 2014; Plate, et al., 2014; Gumucio G. , et al., 2014; Plate, et al., 2014). The objective of this study was to use a rat model to define the age-related alterations in rotator cuff tendon mechanics to determine whether the supraspinatus is more susceptible to injury due to aging than the infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor. We hypothesized that aging would adversely and preferentially affect supraspinatus tendon mechanics when compared to the subscapularis, infraspinatus, and teres minor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Design and Sample Preparation

7-month juvenile (n=16), 18-month adult (n=16), 27-month aged (N=16), and 36-month geriatric (n=16) male F344XBN rats were obtained from the National Institute of Aging (IACUC approved), approximating respective human ages of 18, 43, 63, and 90 years old. After sacrifice, a total of 16 left shoulders were harvested per group for quasi-static and viscoelastic testing, while 10 right shoulders were used to evaluate fatigue mechanical properties. Lower and upper subscapularis (LS & US, respectively) (Rathi, Taylor, & Green, 2017), supraspinatus (SS), infraspinatus (IS), and teres minor (TM), muscle-tendon complexes were then each carefully dissected from the scapula of the right shoulder and removed with the proximal humerus for mechanical testing. Muscle, along with extraneous tissue was removed from each tendon and cross-sectional area of each tendon was measured using a custom laser device (Favata, 2006). Each humerus was potted in a custom acrylic cylinder secured with polymethyl-methacrylate, leaving the proximal humerus exposed. The head of the humerus was secured using a selftapping screw to prevent failure at the growth plate. Custom fixtures were fabricated to test each tendon on-axis with respect to its insertion site into the proximal humerus.

Quasi-static and Viscoelastic Mechanical Testing

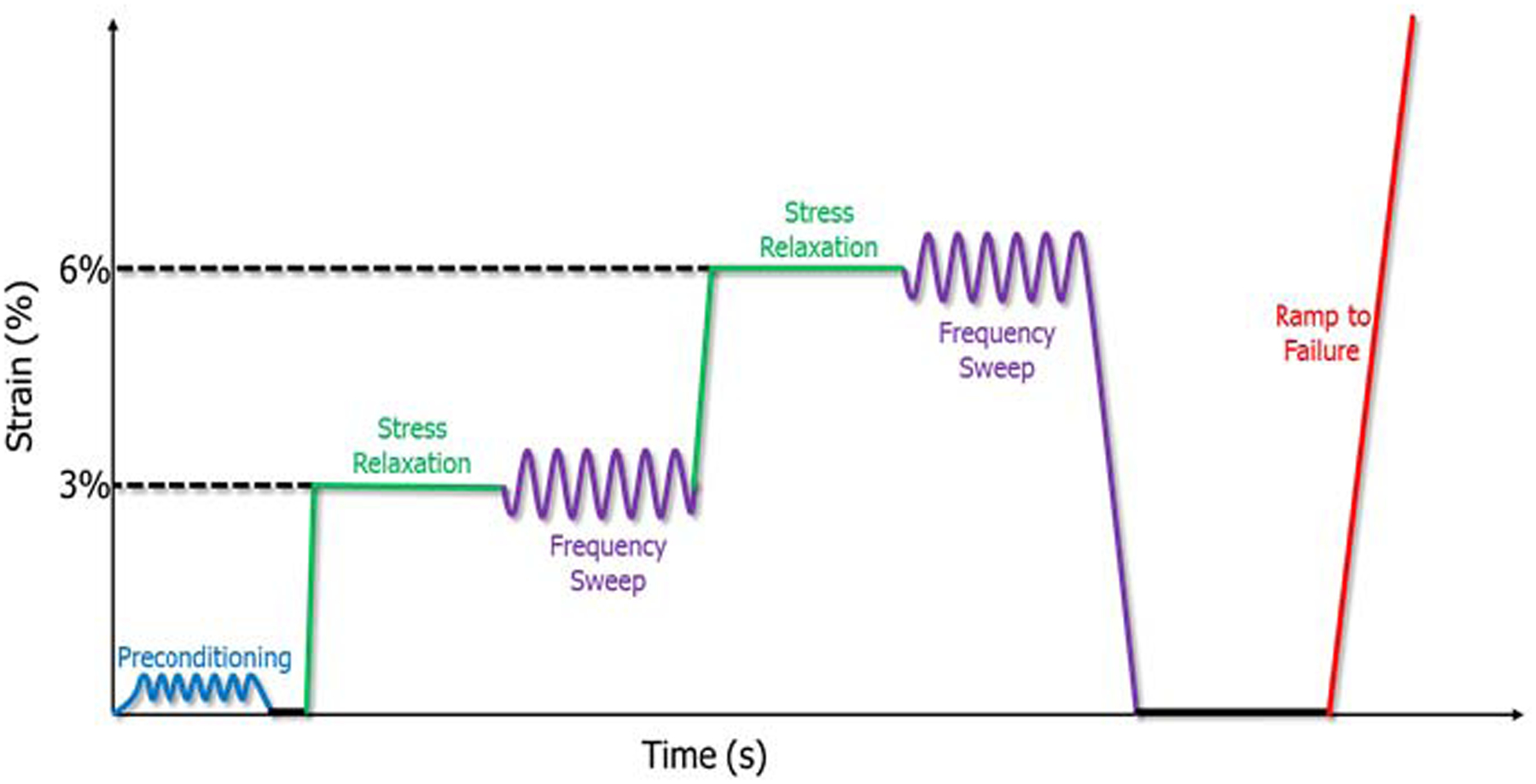

The LS, US, SS, IS, and TM from each animal were mechanically tested independently on an Instron ElectroPuls E3000 (Instron Inc., Norwood, MA). The testing protocol consisted of a 0.1N preload; preconditioning (30 cycles, 0.125% to 0.375% strain, 0.25 Hz); stress relaxation at 3% strain magnitude for 600s; frequency sweep at 3% strain (+/− 0.1875% strain at 0.1 Hz, 1.0 Hz, 2.0 Hz, and 10.0 Hz); stress relaxation at 6% strain magnitude for 600s; frequency sweep at 6% strain (+/− 0.1875% strain at 0.1 Hz, 1.0 Hz, 2.0 Hz, and 10.0 Hz); 300s rest at 0% strain; and a ramp to failure at 0.15% strain/second (Figure 1). Percent relaxation was calculated from each stress relaxation, dynamic modulus and tan(δ) from the frequency sweeps, and a bilinear fit was used to determine linear and toe stiffness from the ramp-to-failure load-displacement curve.

Figure 1:

Quasi-static viscoelastic mechanical testing protocol for LS, US, SS, IS, and TM. Preconditioning followed by stress relaxations and frequency sweeps at 3% and 6% strain, ending with a ramp to failure.

Fatigue Mechanical Testing

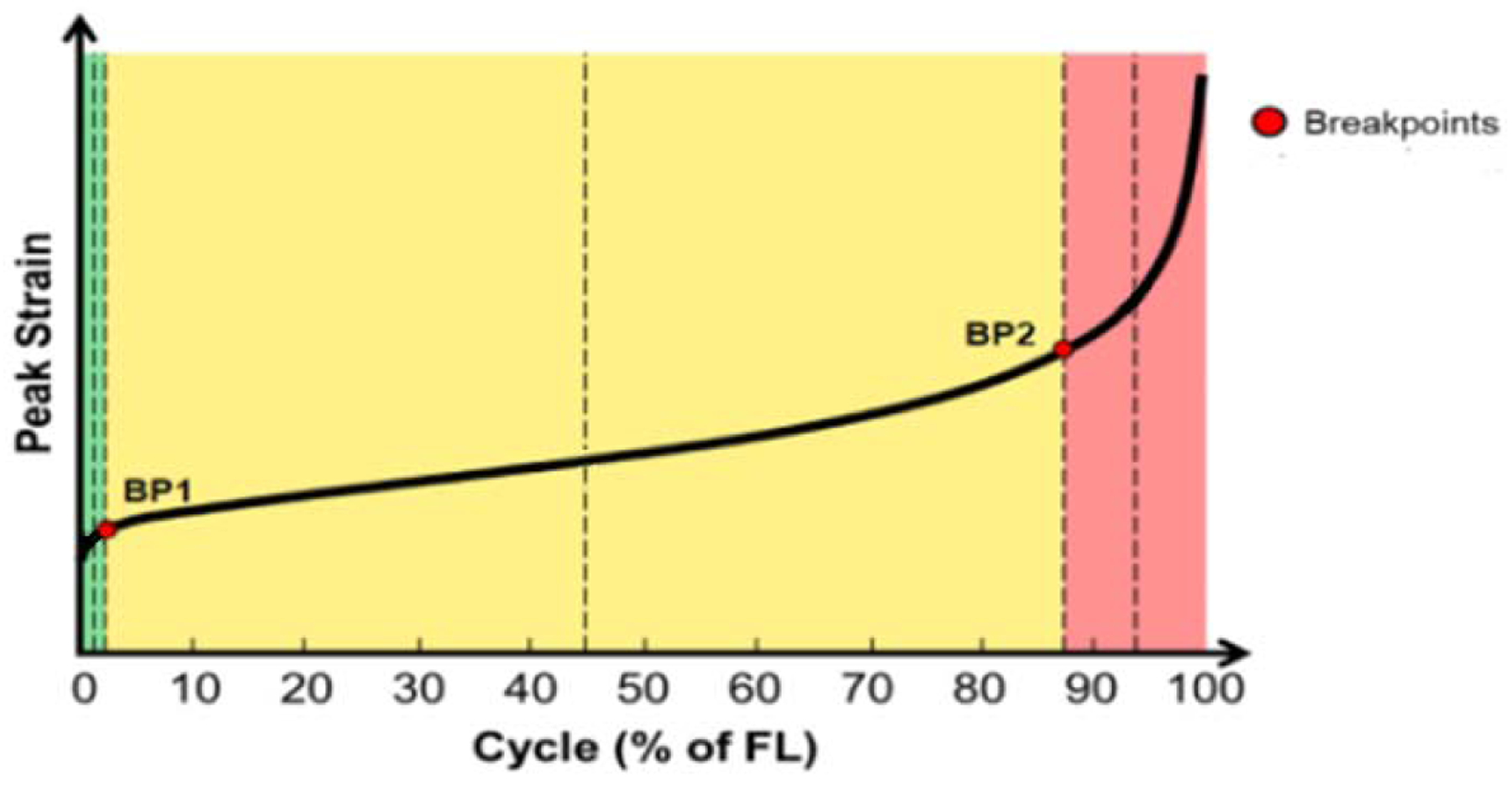

Maximum stresses were calculated from previous ramp to failure testing on contralateral shoulders for each tendon for each group. Mechanical testing consisted of a 0.1N preload, a ramp to 40% maximum stress at 1% strain per minute, and cyclic loading until failure (7–40% maximum load at 2Hz). During loading, force and displacement data were acquired and analyzed using a custom code (Matlab R2015a, Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA). A triphasic line was fit to the peak strain vs. cycles curve for each tendon (Figure 2), with an initial rapid increase in peak cyclic strain (primary phase), a longer steady increase in strain (secondary phase), and an accelerated increase in strain until failure (tertiary phase). All fatigue parameters were calculated at breakpoints 1 (BP1) and 2 (BP2), demarking a transition from the primary to secondary phase, and secondary to tertiary phase, respectively. This allows for consistent comparisons between tests at both early and late cycles during the fatigue loading protocol, respectively. Cycles to failure, secant modulus and stiffness, peak strain, laxity (resistance of material to elastic deformation), and hysteresis (measure of energy dissipation) were evaluated.

Figure 2:

Example peak strain vs cycles (% of failure, FL) curve. Fatigue parameters were calculated at breakpoints 1 (BP1), and breakpoints 2 (BP2)

Statistics

Data sets were tested for normality using D’Agostino normality tests. For normal data, a 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc tests were used to compare the difference ages for each tendon with significance set to p<0.05. For non-parametric data, Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare among age groups for each tendon with significance set to p<0.05.

RESULTS

Aging Affects Cross Sectional Area, Stiffness, and Viscoelasticity at Higher Strains

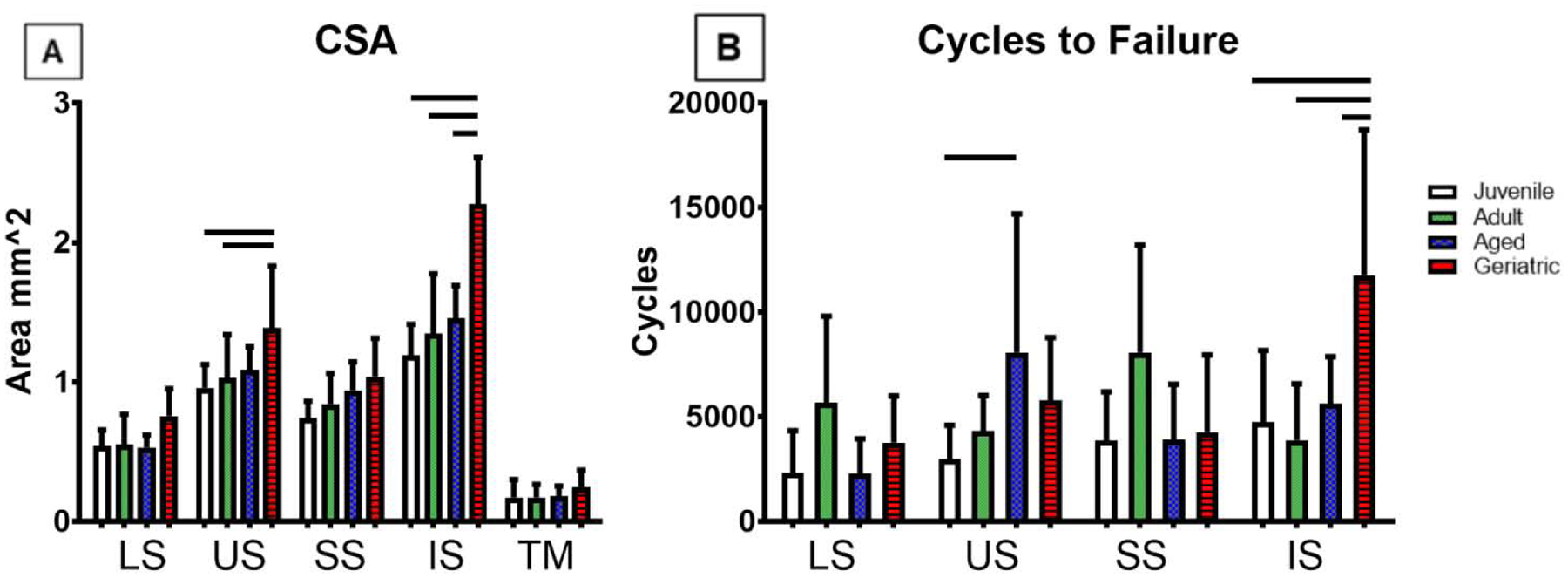

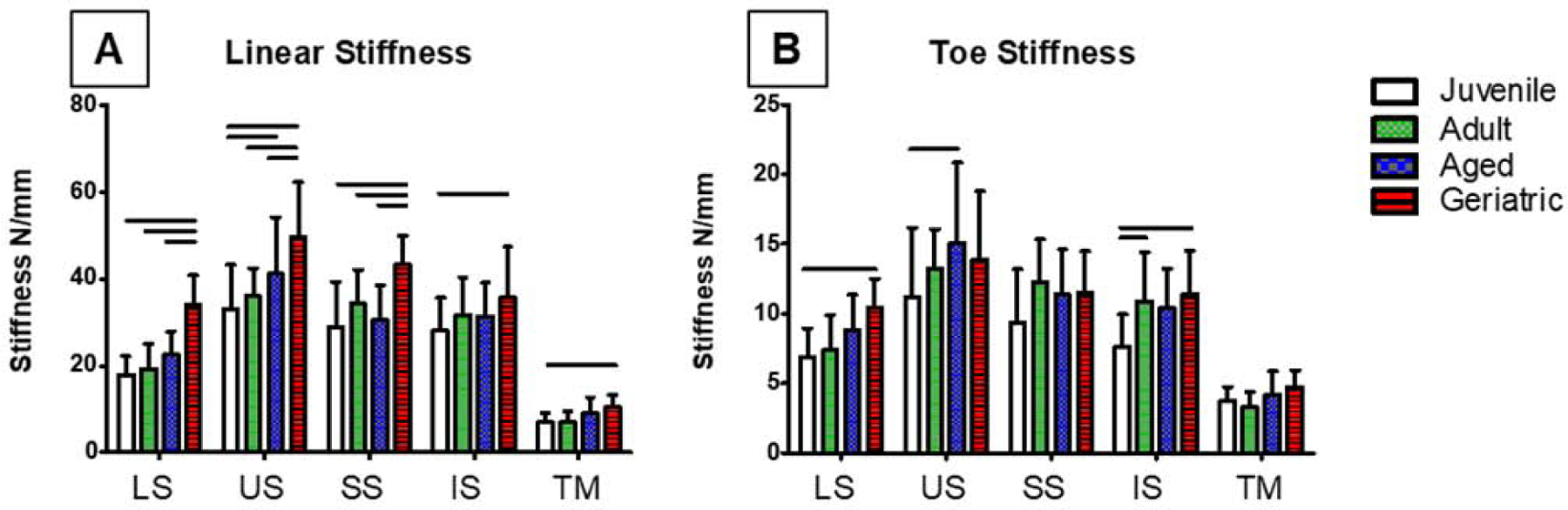

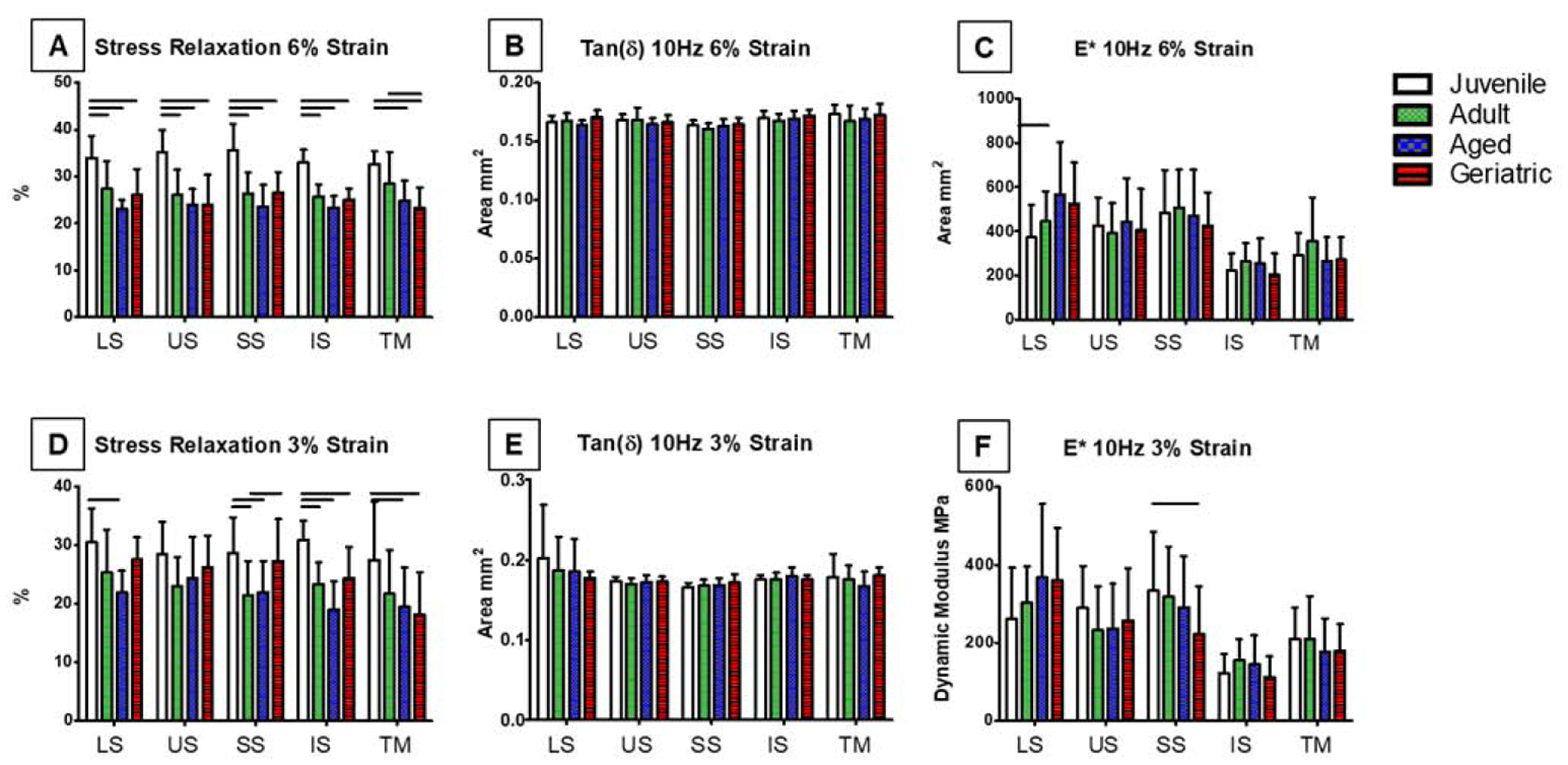

Cross sectional area increased in US and IS geriatric animals (Figure 3A), and cycles to failure peaked in US aged and IS geriatric tendons (Figure 3B). Linear stiffness increased in all tendons in the geriatric animals (Figure 4A), while toe region stiffness only increased in LS, US, and IS tendons (Figure 4B). Stress relaxation was significantly reduced compared to the juvenile animals in all tendons at 6% strain (Figure 5A). In contrast, aging resulted in no changes in tan(δ), and dynamic modulus only showed differences in the LS (Figure 5B, C). At 3% strain, aging decreased stress relaxation in all tendons except the US with no changes found in tan(δ), and SS dynamic modulus decreased in geriatric tendons (Figure 5D–F). No changes were found in insertion-site or mid-substance moduli (data not shown).

Figure 3:

Cycles to failure was increase in US aged and IS geriatric animals (A). Cross sectional area (CSA) increased in US and IS geriatric groups (A, B). Data presented as mean +/− standard deviation, bars indicate significance (p<0.05).

Figure 4:

Linear stiffness increased in all tendons in aged animals (A), and toe stiffness increased in LS, US, and IS (B). Data presented as mean +/− standard deviation, bars indicate significance (p<0.05).

Figure 5:

Stress relaxation was significantly reduced compared to the juvenile animals in all tendons at 6% strain (A). No changes were found in tan(δ) at 6% strain (B) (only 10Hz shown). Dynamic modulus increased in LS at 6% strain in geriatric rats (C). Stress relaxation decreased in LS, SS, IS, and TM at 3% strain compared to juvenile animals (D). Tan(δ) showed no significant changes at 3% strain (E). Dynamic modulus decreased in SS geriatric tendons at 3% strain (F). Data presented as mean +/− standard deviation, bars indicate significance (p<0.05).

Aging Affects Fatigue Mechanics in All Rotator Cuff Tendons Tested, Especially in Later Fatigue Cycles

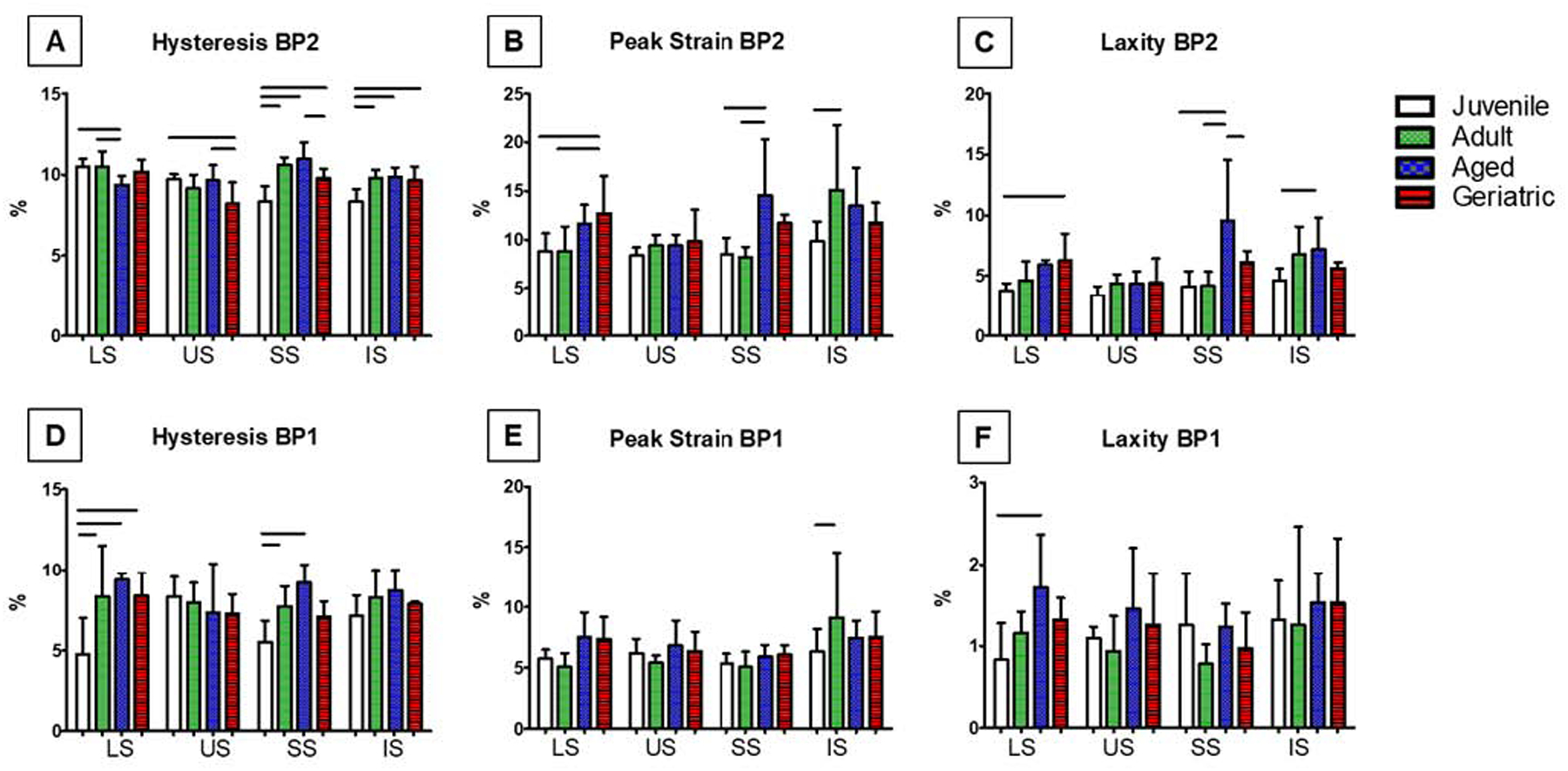

Geriatric animals showed decreases in secant modulus, secant stiffness, and/or tangent modulus in all tendons in later fatigue cycles at BP2 (Figure 6A–C). However, these differences were not consistently observed at BP1 earlier in fatigue loading (Figure 6D–F). No changes were found in tangent stiffness at either breakpoint (not shown). Hysteresis significantly decreased in the LS tendon from juvenile and adult animals to aged, and decreased in the US from juvenile and aged animals to geriatric. Hysteresis was lowest in the juvenile groups for both the SS and IS (Figure 7A). Laxity was higher in the LS geriatric compared to juvenile, SS aged compared to all other ages, and IS aged compared to juvenile animals (Figure 7B–C). These significant differences were not found at BP1 in these parameters with the exception of SS hysteresis, LS laxity, and IS peak strain (Figure 7D–F).

Figure 6:

Significant decrease was seen in LS, SS, and IS secant modulus at BP2 (A). BP2 Secant stiffness decreases in US and IS with age (B). Tangent modulus decreased in LS, US, and IS in aging tendons at BP2 (C). Secant modulus decreased in LS and IS with aging at BP1 (D). No differences were found in secant stiffness at BP1 (E). Tangent modulus significantly decreased at BP1 with aging in LS and IS (F). Data presented as mean +/− standard deviation, bars indicate significance (p<0.05).

Figure 7:

Hysteresis was significantly altered in all tendons with aging at BP2 (A). BP1 peak strain and laxity peaked in aging LS, SS, and IS tendons (B, C). LS and SS hysteresis increased with age at BP1 (D). IS peak strain increases in IS adult tendons at BP1 (E). Laxity at BP1 only peaked in LS aged tendons (F). Data presented as mean +/− standard deviation, bars indicate significance (p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

Though advancing age leads to significantly more supraspinatus tears compared to the other tendons of the rotator cuff (Minagawa, et al., 2013; Kempf, et al., 1999), the age-related changes in tendon mechanical properties that may predispose to preferential supraspinatus injury are unclear. The purpose of our study was to evaluate the fatigue, viscoelastic, and quasi-static mechanics of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, upper and lower subscapularis, and teres minor in an aging rat model. All rotator cuff tendons tested showed significant changes with aging, particularly in geriatric animals; however, the supraspinatus was not preferentially affected by these changes, and thus, the age-related increase in supraspinatus tears cannot be attributed to biomechanical alterations alone.

Overall, none of the tendons tested were preferentially affected by aging. All rotator cuff tendons exhibited significant decreases in stress relaxation, a measure of tendon viscoelasticity that is exacerbated at higher strain levels and indicative of reduced capacity to adapt to applied load. Previous literature describes using such measurements of tendon viscoelasticity as tools for assessing tendinopathy (Surdam, et al., 2015). These results are supported by several recent studies that also found reduced viscoelastic properties with aging in mouse supraspinatus (Connizzo, Sarver, Iozzo, Birk, & Soslowsky, 2013), rat Achilles tendons (Nielsen, Skalicky, & Viidik, 1998), and human flexor tendons (Hubbard & Soutas-Little, 1984), suggesting that aging may have the same effect on viscoelastic properties across multiple tendon types. Changes in viscoelastic properties of tendon may be indicative of alterations in ECM composition from aging and subsequent water content within the tendon (Legerlotz, Riley, & Screen, 2013).

All rotator cuff tendons showed significant increases in linear stiffness in the geriatric age group. It is theorized that during maturation and aging, collagen cross-linking occurs, subsequently increasing stiffness (Shadwick, 1990). Advanced glycation end-products also accumulate during aging, leading to collagen cross-linking and further increasing stiffness (Shadwick, 1990). However, other literature suggests that increases in stiffness mainly occur in maturation and are only minimally affected by aging (Hubbard & Soutas-Little, 1984; Connizzo, Sarver, Iozzo, Birk, & Soslowsky, 2013).

All tendons showed a reduction in either secant modulus, secant stiffness, or tangent modulus, contradictory to an increase in stiffness and no changes in modulus in ramp-to-failure testing. It has been suggested that decreases in these fatigue properties are indicative of an accumulation of damage throughout the cyclic loading protocol (Wren, Lindsey, Beaupre, & Carter, 2003). While there is some evidence that dynamic properties change with age in tendon (Vogel, 1983), further evidence is needed to draw clear conclusions on the mechanisms behind these changes.

In hysteresis, geriatric animals showed significant differences from juvenile rats in all tendons, aged animals showed significant changes from juvenile in LS, SS, and IS tendons, and adult animals showed significant changes from juvenile rats in LS, SS, and IS tendons at either BP1 or BP2, indicating a differential response to cyclic loading and material potential for elastic energy recovery (Maganaris & Narici, 2005); though it should be noted that hysteresis increased in the SS and IS, and decreased in the LS and US with aging. Studies on the mechanical changes in rat tail tendons and cadaveric flexor tendons found that hysteresis was considerably influenced by maturation, but only a minor degree by aging (Vogel, 1983; Hubbard & Soutas-Little, 1984). Increases in peak strain and laxity in the lower subscapularis, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus indicate increases in nonrecoverable length during cyclic loading (Freedman, Zuskov, Sarver, Buckley, & Soslowsky, 2015). Similar work found a surprising lack of differences in aging Achilles tendon peak stress and laxity during fatigue loading (Pardes, et al., 2017); however, this may be described by the differential roles of rotator cuff and Achilles tendon, as the latter is more heavily involved in cyclic loading and less likely to respond to fatigue due to its role in ambulation. Interestingly, more significant changes from aging were found at higher percent strains and in later fatigue cycles, suggesting a significant response to fatigue and higher strain levels. Rotator cuff tears are generally non-traumatic, resulting from an accumulation of damage over time (Yamamoto, et al., 2010), and these results suggest that aging has a more significant effect in these later cycles where tendons are more prone to rupture.

It is unclear why would aging preferentially affect the supraspinatus. Our results indicate that aging results in similar adverse effects across all rotator cuff tendons, thus we cannot determine why supraspinatus tears are most common. It has long been discussed whether intrinsic factors associated with degeneration of the rotator cuff tendons or extrinsic mechanisms defined as factors which can lead to compression of rotator cuff tendons, are the primary reason for rotator cuff pathology (Seitz, McClure, Finucane, Boardman, & Michener, 2010). Previous literature suggests that extrinsic mechanisms such as subacromial spurring and impingement (Neer, 1972; Neer, 1983), and internal impingement (Burkhart, Morgan, & Kibler, 2003; Jobe, 1995; Kibler, 1998; Kvitne & Jobe, 1993) can lead to the development of rotator cuff pathology. However, other studies suggest that intrinsic mechanisms such as biology, mechanics, morphology, vascularity, and gene predisposition may have a more predominant effect than previously believed (Iannoti, et al., 1991; Biberthaler, et al., 2003; Kumagai, Sarkar, & Uhthoff, 1994; Lake, Miller, Elliot, & Soslowsky, 2009; Harvie, et al., 2004). However, it is likely that a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms play a role in the predominance of supraspinatus tears with aging. It is also important to discuss the shared characteristics between the rat and human condition in order to appropriately contextualize this study. In both species, the supraspinatus passes beneath the acromion, potentially leading to compressive forces on the tendon from the acromion (external impingement) during locomotion in the rat and during overhead movement in humans (Soslowsky, Carpenter, DeBano, Banerji, & Maolii, 1996, Schneeberger, Nyffeler, Gerber, 1998). Intrinsic mechanisms such as biology, mechanics, morphology, vascularity, and gene predisposition are also shared between species (Zumstein, Ladermann, Raniga, Schar & 2016; Soslowsky, Carpenter, DeBano, Banerji, & Maolii, 1996; Riggin, et al., 2020; Longo, Berton, Papaietro, Maffulli, & Denaro, 2011). In this study, our results demonstrate that almost all mechanical properties of all rotator cuff tendons change with age, suggesting a common intrinsic mechanism across tendons. However, literature suggests that the supraspinatus is more commonly torn with advancing age, perhaps extrinsic mechanisms may have a key role in the higher incidence of supraspinatus pathology.

This is the first study to directly compare the differential effect of aging on all rotator cuff tendons in rats. However, there are limitations to this study. While the rat rotator cuff well represents the human condition (Soslowsky, Carpenter, DeBano, Banerji, & Maolii, 1996), we did not find any spontaneous ruptures, even in our oldest animals. This is contrary to human rotator cuff tendons where up to 50% of the general population experiences a rotator cuff tear by age 70 (Minagawa, et al., 2013). Additionally, there are predisposing factors that may increase the incidence of rotator cuff tears in humans such as smoking, diabetes, elevated cholesterol, and activity level, that are not replicated in this rat model (Mall, Tanaka, Choi, & Paletta, 2014). No biological or biochemical factors were examined. Aging can result in accumulation of advanced glycation end-products, increased collagen crosslinking, fatty infiltration, and decreased fiber alignment in the supraspinatus tendon (Connizzo, Sarver, Iozzo, Birk, & Soslowsky, 2013; Gumucio J., et al., 2014; Yamamoto, et al., 2010). However, it is expected that these factors would result in significant alterations in tendon mechanics, and would be reflected in this study (Connizzo, Sarver, Iozzo, Birk, & Soslowsky, 2013; Chung, et al., 2016).

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that aging has a significant effect on mechanical properties of the rat rotator cuff, though the supraspinatus was not preferentially affected. Specifically, we utilized a well-established animal model to investigate how the rotator cuff tendon viscoelastic, quasi-static, and fatigue mechanical properties vary with age. Our results indicate that the supraspinatus is not preferentially affected by aging, compared to the other rotator cuff tendons, suggesting a common intrinsic mechanism across tendons. Though mechanical properties were similarly affected in all rotator cuff tendons with aging, biological and structural factors, or extrinsic mechanisms may explain the predominance of supraspinatus tears with age. Previous literature suggests an altered biochemical and structural environment may be present within the rat rotator cuff tendons, and further investigation is necessary. Future studies will investigate the histological, morphological, and biochemical changes in all rotator cuff tendons and muscle in response to aging.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by NIH/NIAMS (R01AR064216) and the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (P30AR069619).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Study Approved By: University of Pennsylvania IACUC

REFERENCES

- Biberthaler P, Wiedemann E, Nerlich A, Kettler M, Mussack T, Deckelmann S, & Mutschler W, 2003. Microcirculation Associated With Degenerative Rotator Cuff Lesions. In Vivo Assessment With Orthogonal Polarization Spectral Imaging During Arthroscopy of the Shoulder. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 85(3), 475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart S, Morgan C, & Kibler W, 2003. The Disabled Throwing Shoulder: Spectrum of Pathology Part III: The SICK Scapula, Scapular Dyskinesis, the Kinetic Chain, and Rehabilitation. Arthroscopy, 19(6), 641–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, & Bedi A, 2010. Rotator Cuff Defect: Acute or Chronic? Journal of Hand Surgery, 36(3), 513–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Park H, Kwon J, Choe G, Kim S, & Oh J, 2016. Effect of Hypercholesterolemia. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(5), 1153–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connizzo B, Sarver J, Iozzo R, Birk D, & Soslowsky L, 2013. Effect of Age and Proteoglycan Deficiency on Collagen Fiber Re-Alignment and Mechanical Properties in Mouse Supraspinatus Tendon. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 135(2), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang A, & Davies M 2018. Rotator Cuff Disease: Treatment Options and Considerations. Sports Medicine Arthroscopic Review 26 (3): 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein L, Thomas S, & Soslowsky L, 2011. Rotator Cuff Tears: What have we learned from animal models? Journal of Musculoskeletal Neuronal Interactions, 11(2), 150–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favata M, 2006. Scarless healing in the fetus: implications and strategies for postnatal tendon repair. PhD Thesis, University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Flahiff C, Brooks A, Hollis J, Schilden J, & Nicolas R, 1995. Biomechanical analysis of patellar tendon allografts as a function of donor age. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 23(3), 354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman B, Zuskov A, Sarver J, Buckley M, & Soslowsky L, 2015. Evaluating Changes in Tendon Crimp with Fatigue Loading as an ex vivo Structural Assessment of Tendon Damage. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 33(6), 904–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung D, Wang V, Andarawis-Puri N, Basta-Pljakic J, Li Y, Laudier D, & Flatow E, 2010. Early response to tendon fatigue damage accumulation in a novel in vivo model. Journal of Biomechanics, 43(2), 274–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumucio G, Korn M, Saripalli A, Flood M, Phan A, Roche S, & Mendias C, 2014. Agingassociated Exacerbation in Fatty Degeneration and Infiltration After Rotator Cuff Tear. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 23(1), 99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvie P, Osterlere S, Teh J, McNally E, Clipsham K, Burston B, & Carr A, 2004. Genetic Influences in the Aetiology of Tears of the Rotator Cuff. Sibling Risk of a Full-Thickness Tear. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 86(5), 696–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard R, & Soutas-Little R, 1984. Mechanical Properties of Human Tendon and Their Age Dependence. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 106(2), 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannoti J, Zlatkin M, Esterhai J, Kressel H, Dalinka M, & Spindler K, 1991. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Shoulder. Sensitivity, Specificity, and Predictive Value. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 73(1), 17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe C, 1995. Posterior Superior Glenoid Impingement: Expanded Spectrum. Arthroscopy, 11(5), 530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jognson G, Tramaglini D, Levine R, Ohno K, Choi N, & Woo S, 1994. Tensile and viscoelastic properties of human patellar tendon. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 12(6), 796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf J, Gleyze P, Bonnomet F, Walch G, Mole D, Beaufils P, & Jaffe A, 1999. A multicenter study of 210 rotator cuff tears treated by arthroscopic acromioplasty. Arthroscopy, 15(1), 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibler W, 1998. The Role of the Scapula in Athletic Shoulder Function. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(2), 325–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai J, Sarkar K, & Uhthoff H, 1994. The Collagen Types in the Attachment Zone of Rotator Cuff Tendons in the Elderly: An Immunohistochemical Study. Journal of Rheumatology, 21(11), 2096–2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvitne R, & Jobe F, 1993. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Anterior Instability in the Throwing Athlete. Clinical Orthopaedic Related Research, (291), 107–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCroix A, Duenwald-Kuehl S, Brickson S, Akins T, Diffee G, Aiken J, & Lakes R, 2013. Effect of Age and Exercise on the Viscoelastic Properties of Rat Tail Tendon. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 41(6), 1120–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake S, Miller K, Elliot D, & Soslowsky L, 2009. Effect of fiber distribution and realignment on the nonlinear and inhomogeneous mechanical properties of human supraspinatus tendon under longitudinal tensile loading. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 27(12), 1596–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legerlotz K, Riley G, & Screen H, 2013. GAG depletion increases the stress-relaxation response of tendon fascicles, but does not influence recovery. Aca Biomaterialia, 9(6), 6860–6866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo U, Berton A, Papapietro N, Maffulli N, & Denaro V, 2011. Epidemiology, genetics and biological factors of rotator cuff tears. Medicine and Sports Science. 57(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maganaris C, & Narici V, 2005. Mechanical Properties of Tendons. Tendon Injuries, 1(1), 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Maganaris D, 2001. In vivo tendon mechanical properties in young adults and healthy elderly. Proceedings of the Active Life Span Research Symposium. [Google Scholar]

- Mall N, Tanaka M, Choi L, & Paletta G, 2014. Factors affecting rotator cuff healing. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 96(9), 778–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R, Thunes J, Spandan M, Musahl V, & Debski R, 2018. Effects of Tendon Degeneration on Predictions of Supraspinatus Tear Propagation. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 47(1), 154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minagawa H, Yamamoto N, Abe H, Fukuda M, Seki N, Kikuchi K, & Itoi E, 2013. Prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears in the general population: From mass-screening in one village. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 10(1), 8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto T, Inui H, Ninomiya H, Tanaka H, & Nobuhara K, 2017. Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes in Overhead Sports Athletes after Rotator Cuff Repair. Journal of Sports Medicine, 2017(1), 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Rokuuma N, Hamada K, Tomatsu T, & Fukuda H, 1994. Histologic and biomechanical characteristics of the supraspinatus tendon: Reference to rotator cuff tearing. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 3(2), 97–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neer C, 1972. Anterior Acromioplasty for the Chronic Impingement Syndrome in the Shoulder: A Preliminary Report. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 54(1), 41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neer C, 1983. Impingement Lesions. Clinical Orthopaedic Related Research(173), 70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen H, Skalicky M, & Viidik A, 1998. Influence of physical exercise on aging rats. III. Lifelong exercise modifies the aging changes of the mechanical properties of limb muscle tendons. Mechanics of Ageing and Developmentq, 100(3), 243–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardes A, Beach Z, Raja H, Rodriguez A, Freedman B, & Soslowsky L, 2017. Aging leads to inferior Achilles tendon mechanics and altered ankle function in rodents. Journal of Biomechanics, 60, 30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plate J, Brown P, Walters J, Clark J, Smith T, Freehill M, & Mannava S, 2014. Advanced Age Diminishes Tendon-To-Bone Healing in a Rat Model of Rotator Cuff Repair. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(4), 859–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plate J, Pace L, Seyler T, Moreno R, Smith T, Tuohy C, & Mannava S, 2014. Agerelated Changes Affect Rat Rotator Cuff Muscle Function. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 23(1), 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathi S, Taylor N, & Green R, 2017. The upper and lower segments of subscapularis muscle have different roles in glenohumeral joint functioning. Journal of Biomechanics, 3, 92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G, 2004. Cross-linking in collagen by nonenzymatic glycation increases the matrix stiffness in rabbit achilles tendon. Experimental Diabesity Research, 5(2), 143–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggin C, Rodriguez A, Weiss S, Raja H, Chen M, Schultz S, Sehgal C, & Soslowsky L, 2020. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Seitz A, McClure P, Finucane S, Boardman D, & Michener L, 2010. Mechanisms of Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: Intrinsic, Extrinsic, or Both? Clinical Biomechanics, 26(1), 112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadwick R, 1990. Elastic energy storage in tendons: mechanical differences related to function and age. Journal of Applied Physiology, 68(3), 1033–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, & Maffulli N, 2006. Biology of tendon injury: healing, modeling and remodeling. Journal of Musculoskeletal Neuronal Interactions, 6(2), 181–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeberger A, Nyffler R, & Gerber C, 1998. Structural changes of the rotator cuff caused by experimental subacromial impingement in the rat. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 7(4), 375–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soslowsky L, Carpenter J, DeBano C, Banerji B, & Maolii M, 1996. Development and use of an animal model for investigations on rotator cuff disease. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 5(5), 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soslowsky L, Thomopoulos S, Tun S, Flanagan C, Keefer C, Mastaw J, & Carpenter J, 2000. Neer Award 1999. Overuse activity injures the supraspinatus tendon in an animal model: a histologic and biomechanical study. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 9(2), 79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steplewski A, Fertala J, Tomlinson R, Hoxha K, Han L, Thakar O, & Fertala A, 2017. The impact of cholesterol deposits on the fibrillar architecture of the Achilles tendon in a rabbit model of hypercholesterolemia. Journal of Othopaedic Surgery and Research, 14(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surdam S, Soulas E, Elliot D, Silbernagel K, Buchanan T, & Cortes D, 2015. Viscoelastic Properties of Healthy Achilles Tendon are Independent of Isometric Plantar Flexion Strength and Cross-Sectional Area. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 33(6), 926–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan M, Sato E, Galatz L, Thomopoulos S, & Ward S, 2014. The Effect of Age on Rat Rotator Cuff Muscle Architecture. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 23(12), 1786–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel H, 1983. Age dependence of mechanical properties of rat tail tendons (hysteresis experiments). Aktuelle Gerontol, 13(1), 22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren T, Lindsey D, Beaupre G, & Carter D, 2003. Effects of creep and cyclic loading on the mechanical properties and failure of human Achilles tendons. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 31(6), 710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto AT, Osawa T, Yanagawa T, N. D, Shitara H, & Kobayashi T, 2010. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 19(1), 116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T, Tasi W, Cheng J, Yang Y, Liang F, & Chen C, 2012. The effects of aging on quantitative sonographic features of rotator cuff tendons. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound, 40(8), 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T, Tasi W, Cheng J, Yang Y, Liang F, & Chen C, 2012. The effects of aging on quantitative sonographic features of rotator cuff tendons. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound, 392 40(8), 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]