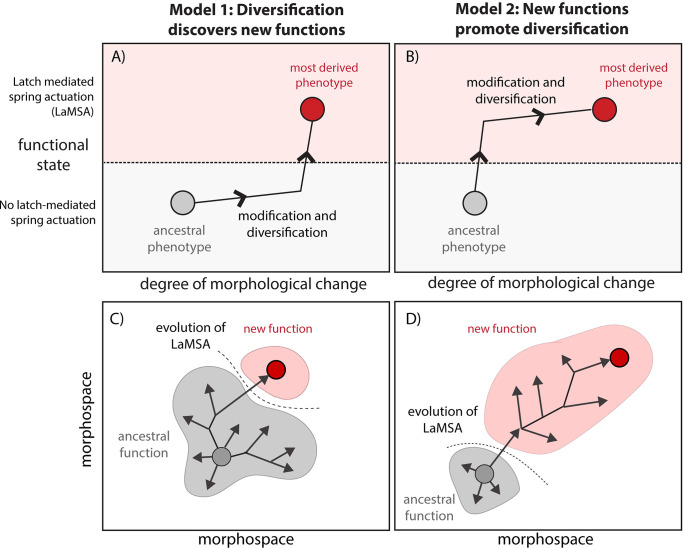

Fig 1. Conceptual diagram showing contrasting hypotheses for a functional and morphological transitions during biomechanical innovation.

Biomechanical innovations involve both functional and morphological changes. In one model (A, C), derived morphologies (in this case, modification of the mandible apparatus) diversify first either through neutral variation or adaptation to other functions, and only finally does the new emergent function (in this case, latch-mediated spring actuation, LaMSA) evolves after morphology is highly derived. Alternatively (B, D), the new function evolves through very minor morphological changes, followed by subsequent large diversification in form to explore a new adaptive landscape, reaching new optima for the new function. Our study supports the latter model for trap-jaw mandibles in Strumigenys ants.