Abstract

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory disease with complicated pathophysiology that involves genetic and environmental elements and dysregulation of innate and adaptive immunity, neurovascular responses, microbiome colonization or infection, resulting in recurrent inflammation. Rosacea has been reported associated with various gastrointestinal diseases including inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease, Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection, and small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). The link may involve common predisposing genetic, microbiota, and immunological factors, comprising the theory of the gut–skin axis. Although the evidence is still controversial, interestingly, medications for eradicating SIBO and HP provided an effective and prolonged therapeutic response in rosacea, and conventional therapy for which is usually disappointing because of frequent relapses. In this article, we review the current evidence and discuss probable mechanisms of the association between rosacea and gastrointestinal comorbidities.

Keywords: Celiac disease, Gut–skin axis, Helicobacter pylori, Inflammatory bowel disease, Irritable bowel syndrome, Rosacea, Small intestine bacterial overgrowth

Key Summary Points

| Rosacea has been reported to be associated with various gastrointestinal diseases including inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease, Helicobacter pylori infection, and small intestine bacterial overgrowth. |

| Among rosacea-associated gastrointestinal diseases, the evidence for inflammatory bowel disease is the strongest. |

| The link between rosacea and gastrointestinal comorbidities may involve common predisposing genetic, microbiota, and immunological factors, comprising the theory of the gut–skin axis. |

| The associations of rosacea with gastrointestinal diseases remind us of these possible comorbidities and provide an innovate direction for treating rosacea, and conventional therapy for which is usually unsatisfactory because of frequent relapses. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13562315.

Introduction

Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory disease that mainly affects the central face and presents with flushing, persistent erythema, papules and pustules, telangiectasia with or without burning or stinging sensation, dry and rough appearance, facial plaques or edema, phymatous changes, and ocular involvement [1]. Rosacea is classified into four subtypes: erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, papulopustular rosacea, phymatous rosacea, and ocular rosacea [1].

The pathophysiology of rosacea involves genetic and environmental elements and dysregulation of innate and adaptive immunity, neurovascular responses, and microbiome colonization or infection, with resultant chronic recurrent inflammation [2, 3]. Although the exact mechanisms are unclear, rosacea has been associated with many comorbidities such as gastrointestinal, neurologic, cardiovascular, psychiatric, metabolic, and autoimmune diseases [3–5]. Among these comorbidities, the gastrointestinal conditions were the most frequently reported, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) which consists of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), celiac disease (CeD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection, and small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) [3, 5–7]. The gut–skin axis, a newly emerging concept for pathogenesis of many chronic inflammatory diseases, proposes that gastrointestinal health affects the skin homeostasis and allostasis through complicated interactions between the immune, metabolic, and nervous systems [8, 9]. The gut microbiome is regarded as a major regulator of the gut–skin axis with a bidirectional modulation between the gut microbiome and host immunity [8–10]. Perturbations of the gut microbiota would disrupt balance of the immune system not only in the intestinal mucosa but also systemically. Thus, the “leaky gut” theory, noted by increased gut permeability, intestinal dysbiosis, and changed mucosal immunity, has been considered related to the development of chronic inflammatory diseases [10]. In this article, we review the current evidence and discuss probable mechanism of the association between rosacea and gastrointestinal comorbidities. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Gut–Skin Axis: Gut Microbiota as a Link Between Rosacea and Gastrointestinal Comorbidities

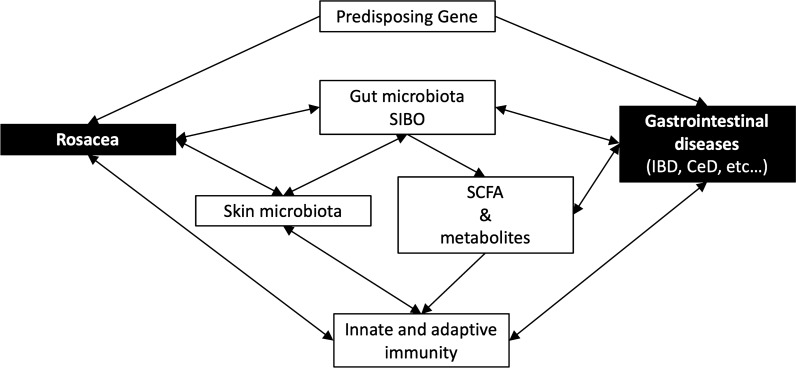

Gut microbiota have been reported to affect skin homeostasis and allostasis through their effects on both innate and adaptive immunity [8]. The gut microbiome can affect the host immune system in a complicated and intricate way, which can promote immune tolerance of dietary and environmental antigens and provide protection against invasion of exogenous pathogens directly by competitively binding to endothelial cells and triggering immunoprotective responses [9]. Segmented filamentous bacteria, a nonculturable Clostridia-related species, orchestrate the differentiation of both proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells and regulatory T cell responses [11]. Certain microbes and their metabolites, such as retinoic acid, and polysaccharide A of Bacteroides fragilis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, were reported to promote regulatory T cells [9, 10]. Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as propionate, acetate, and butyrate, were synthesized from dietary fiber fermentation by the gut microbiome. SCFAs have been found to inhibit inflammatory cells proliferation, migration, adhesion, decrease cytokine production, inhibit histone deacetylase, and inactivate the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathways, and therefore regulate the activation and apoptosis of immune cells and decrease immune response [9, 12]. Not surprisingly, SCFAs have demonstrated protection against the development of inflammatory disorders such as allergy [13]. On the other hand, emerging evidence shows that gut microbiota are supposed to impact the skin microbiota. SCFAs were reported to play a key role in impacting the predominance of skin microbiota and subsequently affect the cutaneous immune response [9]. Also, intestinal microbiota and their metabolites have been found to metastasize to the skin via the bloodstream in cases with disturbed intestinal barriers, accumulate in the skin, and then disrupt skin homeostasis [8, 9]. Skin microbiota are crucial for the balance of skin immunity and defensive function, like a skin barrier. Perturbation of skin microbiota may abnormally enhance the Toll-like receptor 2-related pathway, activate innate immunity, and amplify the inflammatory response to external stimuli in patients with rosacea [14]. The evidence suggests direct interactions among gut microbiota, skin microbiota, and skin homeostasis. Rosacea is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease and diseases of this kind have shown certain evidence associated with gut dysbiosis [15]. Several studies have suggested a relationship of rosacea with HP infection and SIBO, although the role is still controversial [8]. SIBO produces toxic metabolites which induce enterocytes injury and increased intestinal permeability, and thus contributes to systemic inflammation [9, 12]. Various gastrointestinal diseases such as IBD, CeD, and IBS have also been related to SIBO [16–19]. Microbiota have been considered a link between rosacea and gastrointestinal comorbidities (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Probable mechanism for association between rosacea and gastrointestinal comorbidities. CeD celiac disease, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, SCFA short chain fatty acids, SIBO small intestine bacterial overgrowth

Helicobacter pylori Infection

Helicobacter pylori is a type of spiral-shaped gram-negative bacteria known to cause gastritis and peptic ulcer. The association between HP infection and rosacea is controversial. A case–control study has shown a significantly higher prevalence of HP infection in patients with rosacea than in age‐ and sex‐matched controls, and rosacea has been associated with gastritis, especially involving antrum mucosa [20]. In contrast, another case–control study revealed that patients with rosacea had similar rates of HP infection as healthy controls [21]. Also, a study found no increased risk of nonimmunologic gastrointestinal ulcers in patients with rosacea [22]. A meta-analysis of 14 observational studies found a weak but non-significant association between rosacea and HP infection (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.00–2.84, P = 0.052), but a sensitivity analysis restricted to C-urea breath test showed a significant association (OR 3.12, 95% CI 1.92–5.07, P < 0.0001) [23]. The conclusion of that article with the highest level of evidence seems to give us a temporary answer to the conflicting results. However, the relationship between HP infection and rosacea appears more complicated with many confounding factors. Some studies discovered a higher prevalence of HP infection among patients with moderate to severe rosacea, implying a potential dose–response relationship between the severity of rosacea and concurrent HP infection rates [24, 25]. One case–control study found no significant association between exposure to HP and rosacea, but a strong correlation in those without previous antibiotics use (OR 5.19, P = 0.005). The fact is that oral antibiotics are standard treatment options for both diseases, which complicates the interpretation of these findings, and there were two separate studies on patients without previous antibiotic use showing a strong association between rosacea and HP infection [26].

Prolonged use of systemic antibiotics in rosacea may be a confounder in the relationship. Antibiotics could diminish the antigenic effect of HP, and partial treatment of HP can lead to non-reactive serology [27]. Thus, the association between HP infection and rosacea is usually underestimated.

On the other hand, some reports found that eradication of HP successfully treated rosacea, even for patients who failed to improve with prior conventional treatments [28, 29]. However, one meta-analysis of seven studies revealed a trend but no significant effect of HP eradication on rosacea symptoms (RR 1.28, 95% CI 0.98–1.67, P = 0.069) [23]. Actually, reports of improvement in rosacea following antibiotic therapy for HP infection may be attributable to the anti-inflammatory effects of antibiotics used. The association among HP infection, antibiotics effect, and rosacea still needs to be clarified.

Despite the highly conflicting results of current research, there are some reasonable mechanisms to explain the possible association between these two diseases. Rosacea is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease and usually presents with flushing, while HP may induce inflammation and flushing possibly through the release of angiogenic and vasomotor agents. Firstly, HP can increase the in vivo concentrations of nitrous oxide, which induces vasodilation, inflammation, and cytotoxic reaction. HP can also induce delivery of a highly immunogenic protein, cytotoxin-associated gene A, into cells [30] and provoke proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-8, causing a series of inflammatory reactions [27, 30, 31]. On the other hand, gastric HP infection is largely related to hypergastrinemia [32], and gastrin is the endogenous trigger to evoke flushing [30, 33].

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth

SIBO is defined as small bowel aspirate of more than 105 colony-forming unit/ml as a gold standard although the diagnosis could be made by various tools [34]. However, a systematic review demonstrated the limited ability to accurately identify SIBO by current detection methods [34]. This may contribute to variable results between SIBO studies as a result of different detection methods.

A nationwide cohort study found no increased incidence of SIBO in patients with rosacea despite the significant higher prevalence, but the study authors stated that SIBO prevalence might have been underestimated [6]. A prospective study demonstrated SIBO in almost half of patients with rosacea, and the prevalence was significantly higher than in healthy controls. Additionally, most of the SIBO-positive patients with rosacea presented with papulopustular-type rosacea [35]. However, another case–control study found that HP infection, rather than SIBO, was significantly more prevalent and may play a pathogenic role in rosacea [29]. In that study, most patients presented with facial flushing and erythema but only 30% with papulopustules [29]. The results of these studies were consistent with a previously proposed hypothesis that HP seems more prevalent in erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, possibly because HP-related angiogenic and vasomotor agents can induce flushing and erythema. Nevertheless, SIBO played a more important role in papulopustular rosacea [35, 36]. The hypothesis was confirmed by the study by Drago, which showed significant higher risk of SIBO in papulopustular rosacea than in erythematotelangiectatic type (P = 0.018, OR 12.3, CI 1.4–105.5) [37].

After eradication of SIBO by rifaximin 400 mg three times daily for 10 days, almost all of the patients achieved complete resolution or at least great improvement of rosacea [35]. Skin lesions remained in remission without other treatments in these SIBO-eradicated patients for more than 9 months. By contrast, among those who received placebo, skin lesions remained stationary or even worsened until they received SIBO eradication afterwards [35]. Another study with 3 years of follow-up also demonstrated persistent therapeutic effects after eradicating SIBO with rifaximin [37]. In addition, there was a report that eradication of SIBO benefitted ocular rosacea greatly [38]. Rifaximin can diminish SIBO but the poor absorbability resulted in less interference with skin microbiota or systemic anti-inflammatory effect; thus SIBO is suggested to be a determinant in persistent inflammation in rosacea [35, 37]. Actually, for those patients without SIBO, rifaximin use did not improve rosacea symptoms [35].

The underlying mechanism linking SIBO to rosacea remains unelucidated. It has been speculated that SIBO increases intestinal permeability, which results in translocation of bacterial components and proinflammatory cytokines into systemic circulation and then triggers inflammation of the skin [7, 15]. Also, gut bacteria have been shown to mimic immunogens. The existence of SIBO may trigger rosacea by increasing TNF or other cytokines, suppressing IL-17, and stimulating the T helper 1-mediated immune reaction [38, 39]. These results provide a new perspective on the pathogenesis and treatment for rosacea in that dysbiosis may play an important role.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Among rosacea-associated gastrointestinal diseases, the evidence for IBD is the strongest [3]. A recent meta-analysis indicated an increased prevalence of both CD and UC among patients with rosacea [7]. The association appeared stronger for CD than UC [7, 40]. Another meta-analysis found that the association between rosacea and IBD was bidirectional [41].

Rosacea and IBD are both chronic inflammatory diseases involving the interplay between genetic, immunological, and microbiota elements. As for the genetic aspect, the significant single-nucleotide polymorphisms of butyrophilin-like 2, which likely functions in T cell activation, and polymorphisms of glutathione-S-transferase gene, which encodes enzymes that catalyze toxic oxidative intermediates, have been related to both rosacea and IBD [7, 42]. Sociobiologically, rosacea and IBD share common risk factors such as obesity and smoking [7, 43].

In the aspect of immunity, both rosacea and IBD are associated with alterations in innate and adaptive immunity [3]. There have been reports that dysfunction of the innate immune system as activation of macrophages and Toll-like receptor 2, dysregulation of mast cells, fibroblasts, and production of reactive oxygen species, matrix metalloproteinases, TNF, and IL-1β contribute to the development of chronic inflammation and vascular abnormalities, causing inflammation of both rosacea and IBD [3, 7, 44]. For adaptive immunity, T helper type 1 and 17 cells as well as B cells are pathogenic in both rosacea and IBD through production of interferon-gamma (IFNγ), TNF, IL-17, and multiple immunoglobulins [3, 7, 44]. As previously discussed, SIBO is considered linked to rosacea. Similarly, significant higher SIBO has been observed in patients with CD and patients with UC [16], and eradication of SIBO substantially improved clinical symptoms of IBD [7, 45, 46]. Dysbiosis may also play a role in the link between rosacea and IBD. Medication effluence is another possible cause for the association. Patients with rosacea usually received long-term antibiotics, especially tetracycline. A study also demonstrated ever use of tetracycline at baseline was associated with an increased risk for CD and UC [40].

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an immune-mediated, gluten-induced small-intestinal mucosal injury and nutrient malabsorption [47]. A Danish population-based cohort study revealed a significant association of rosacea with incident CeD (HR 1.46, 95% CI 1.11–1.93) [6]. In addition, a case–control study demonstrated that patients with rosacea had a twofold odds for prevalent CeD compared with age, sex, and calendar time-matched controls (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.35–3.07) [4], and stratification by gender revealed a significant association of rosacea with CeD in women, but not in men [4].

Rosacea shares genetic risk loci with CeD. A genome-wide association study (GWAS) found that rosacea was associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DRB1*03:01, HLA-DQB1*02:01, and HLA-DQA1*05:01 [42], and both HLA-DQB1*02:01 and HLA-DQA1*05:01 were associated with CeD [48]. In CeD, the main immune actions were Th1 and B lymphocyte-related response releasing immunoglobulin E and other immunoglobulins and Th2-related releasing of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF and IFNγ [49, 50]. On the other hand, a high prevalence of SIBO in patients with CeD was noted, but the evidence was only stronger in those with persistent gastrointestinal symptoms after gluten-free diet [17, 18]. Rosacea and CeD may share common pathogenesis in gene, immune reaction, and SIBO.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

The pathophysiology of IBS remains uncertain. A Danish population-based cohort study found an increased incidence of IBS in patients with rosacea (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.19–1.50) [6], whereas in the subgroup analysis according to gender, the increased risk for IBS only existed in women (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.19–1.54), but not in men (HR 1.29, 95% CI 0.98–1.69) [6]. However, the data were based on International Classification of Diseases codes, and the diagnosis of IBS should exclude other identified gastrointestinal diseases which had symptoms overlapping those of IBS. The association of rosacea with IBS still needs further evidence.

Rosacea and IBS also share some common pathogenesis. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with IBS produce high levels of TNF [51], which plays a role in the pathogenesis of rosacea. SIBO was also reported to be associated with IBS. It has been reported that 78% of patients with IBS had SIBO, and eradication of the overgrowth eliminated IBS in 48% of subjects [19]. However, some studies did not support an association between SIBO and IBS, with only mildly increased amounts of small-bowel bacteria found [52].

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Only one case–control study reported a significant association between rosacea and GERD (OR 4.2, 95% CI 1.7–10.2) [53]. Some common risk factors, such as smoking and alcohol use, are shared by rosacea and GERD [26, 43, 54, 55]. More studies are awaited to examine the association between the two diseases.

Conclusions

Rosacea is associated with many gastrointestinal comorbidities although the pathogenesis is not yet fully elucidated, which may involve shared common predisposing factors as genetic, microbiota, and immunological elements. Table 1 summarizes the possible mechanisms of the association of rosacea with the gastrointestinal comorbidities we discussed in this article. As illustrated in Fig. 1, some common genetic loci may predispose subjects to both rosacea and gastrointestinal diseases. Also, microbiota and related changes of immunity play an important role in the association. Dysbiosis and SIBO affect the host immune system in a complicated and intricate way, involving both innate and adaptive immunity through changing SCFA, certain intestinal microbes and their metabolites, and the influence on the skin microbiota, and subsequently affect cutaneous immune response. Interestingly, although the evidence is still equivocal, medication for eradicating SIBO and HP seemed to provide an effective and prolonged therapeutic response for rosacea in some studies. Not only do these associations remind us of these gastrointestinal comorbidities among patients with rosacea but also provide an innovate direction for treating rosacea, conventional therapy for which is usually unsatisfactory because of frequent relapses.

Table 1.

Reported common mechanisms of rosacea and each associated gastrointestinal comorbidity

| Gastrointestinal comorbidities | Possible mechanisms of the association |

|---|---|

| Helicobacter pylori infection | HP may induce inflammation and flushing possibly through the release of angiogenic and vasomotor agents. HP can increase nitrous oxide concentrations, which induces vasodilation, inflammation, and cytotoxic reaction. HP can also induce delivery of a highly immunogenic protein, cytotoxin-associated gene A, into cells and provoke proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF and IL-8, causing a series of inflammatory reactions. Also, gastric HP infection is largely related to hypergastrinemia, and gastrin is the endogenous trigger to evoke flushing |

| Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) | SIBO increases intestinal permeability, resulting in translocation of bacterial components and proinflammatory cytokines into systemic circulation and then triggers inflammation of skin. Also, gut bacteria mimic immunogens, so SIBO may trigger rosacea by increasing TNF or other cytokines, suppressing IL-17, and stimulating the T helper 1-mediated immune reaction |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Both rosacea and IBD are associated with alterations in innate and adaptive immunity. Dysfunction of the innate immune system as activation of macrophages and Toll-like receptor 2, dysregulation of mast cells, fibroblasts, and production of reactive oxygen species, matrix metalloproteinases, TNF, and IL-1β contribute to the development of chronic inflammation and vascular abnormalities, causing inflammation of both diseases. For adaptive immunity, T helper type 1 and 17 cells as well as B cells are pathogenic in both rosacea and IBD through production of IFNγ, TNF, IL-17, and multiple immunoglobulins. The common predisposing genes were found, such as the significant polymorphisms of butyrophilin-like 2 and glutathione-S-transferases gene. SIBO is considered linked to both rosacea and IBD. Medication effluence, like ever use of tetracycline in rosacea was associated with an increased risk for CD and UC |

| Celiac disease | Rosacea shares genetic risk loci with CeD, such as HLA-DQB1*02:01 and HLA-DQA1*05:01. In CeD, the main immune actions were Th1 and B lymphocyte-related response releasing immunoglobulin E and other immunoglobulins and Th2-related releasing of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF and IFNγ. On the other hand, a high prevalence of SIBO seems noted in patients with rosacea and patients with CeD |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with IBS produce high levels of TNF, which plays a role in the pathogenesis of rosacea. SIBO was also reported associated with IBS and rosacea, and eradication of SIBO benefit in these two diseases in some evidence |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | Some common risk factors, such as smoking and alcohol use, are shared by rosacea and GERD |

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Fang-Ying Wang and Ching-Chi Chi have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1.Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the national rosacea society expert committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584–587. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwab VD, Sulk M, Seeliger S, et al. Neurovascular and neuroimmune aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:53–62. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2011.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes AD, Spoendlin J, Chien AL, Baldwin H, Chang ALS. Evidence-based update on rosacea comorbidities and their common physiologic pathways. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egeberg A, Hansen PR, Gislason GH, Thyssen JP. Clustering of autoimmune diseases in patients with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:667–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haber R, El Gemayel M. Comorbidities in rosacea: a systematic review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:786–792. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egeberg A, Weinstock LB, Thyssen EP, Gislason GH, Thyssen JP. Rosacea and gastrointestinal disorders: a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:100–106. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang FY, Chi CC. Association of rosacea with inflammatory bowel disease: a moose-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019;98:e16448. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Neill CA, Monteleone G, McLaughlin JT, Paus R. The gut-skin axis in health and disease: a paradigm with therapeutic implications. BioEssays. 2016;38:1167–1176. doi: 10.1002/bies.201600008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salem I, Ramser A, Isham N, Ghannoum MA. The gut microbiome as a major regulator of the gut-skin axis. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1459. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forbes JD, Van Domselaar G, Bernstein CN. The gut microbiota in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1081. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Rakotobe S, Lécuyer E, et al. The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity. 2009;31:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuelson DR, Welsh DA, Shellito JE. Regulation of lung immunity and host defense by the intestinal microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1085. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y-G, Udayanga KGS, Totsuka N, Weinberg JB, Núñez G, Shibuya A. Gut dysbiosis promotes M2 macrophage polarization and allergic airway inflammation via fungi-induced PGE2. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picardo M, Ottaviani M. Skin microbiome and skin disease: the example of rosacea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(Suppl 1):S85–86. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riordan SM, McIver CJ, Thomas DH, Duncombe VM, Bolin TD, Thomas MC. Luminal bacteria and small-intestinal permeability. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:556–563. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah A, Morrison M, Burger D, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:624–635. doi: 10.1111/apt.15133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti G. High prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in celiac patients with persistence of gastrointestinal symptoms after gluten withdrawal. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:839–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Losurdo G, Marra A, Shahini E, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and celiac disease: a systematic review with pooled-data analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29:e13028. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3503–3506. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szlachcic A. The link between Helicobacter pylori infection and rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:328–333. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma VK, Lynn A, Kaminski M, Vasudeva R, Howden CW. A study of the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and other markers of upper gastrointestinal tract disease in patients with rosacea. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:220–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spoendlin J, Karatas G, Furlano RI, Jick SS, Meier CR. Rosacea in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: a population-based case–control study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:680–687. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jørgensen AR, Egeberg A, Gideonsson R, Weinstock LB, Thyssen EP, Thyssen JP. Rosacea is associated with Helicobacter pylori: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:2010–2015. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beridze L, Ebanoidze T, Katsitadze T, Korsantia N, Zosidze N, Grdzelidze N. The role of Helicobacter pylori in rosacea and pathogenetic treatment. Georgian Med News. 2020;298:109–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattarai S, Agrawal A, Rijal A, Majhi S, Pradhan B, Dhakal SS. The study of prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with acne rosacea. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2012;10:49–52. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v10i4.10995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, Hata TR. Rosacea: part i. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonamigo RR, Leite CS, Wagner M, Bakos L. Rosacea and Helicobacter pylori: interference of systemic antibiotic in the study of possible association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:424–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00090-3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolibásová K, Tóthová I, Baumgartner J, Filo V. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori as the only successful treatment in rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1393. doi: 10.1001/archderm.132.11.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gravina A, Federico A, Ruocco E, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection but not small intestinal bacterial overgrowth may play a pathogenic role in rosacea. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:17–24. doi: 10.1177/2050640614559262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dundon WG, de Bernard M, Montecucco C. Virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori. Int J Med Microbiol. 2001;290:647–658. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(01)80002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori and rosacea: review and discussion. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:318. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3232-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson WL, Barnett CC, Evans DJ, Jr, et al. Acid secretion and serum gastrin in normal subjects and patients with duodenal ulcer: the role of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:2038–2043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frölich JC, Bloomgarden ZT, Oates JA, McGuigan JE, Rabinowitz D. The carcinoid flush. Provocation by pentagastrin and inhibition by somatostatin. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:1055–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197811092991908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khoshini R, Dai S-C, Lezcano S, Pimentel M. A systematic review of diagnostic tests for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1443–1454. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parodi A, Paolino S, Greco A, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in rosacea: clinical effectiveness of its eradication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:759–764. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rebora A, Drago F, Picciotto A. Helicobacter pylori in patients with rosacea. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1603–1604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drago F, De Col E, Agnoletti AF, et al. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in rosacea: a 3-year follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:e113–e115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinstock LB, Steinhoff M. Rosacea and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: prevalence and response to rifaximin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:875–876. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2–11. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2011.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li W-Q, Cho E, Khalili H, Wu S, Chan AT, Qureshi AA. Rosacea, use of tetracycline, and risk of incident inflammatory bowel disease in women. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han J, Liu T, Zhang M, Wang A. The relationship between inflammatory bowel disease and rosacea over the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2019;43:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang ALS, Raber I, Xu J, et al. Assessment of the genetic basis of rosacea by genome-wide association study. J Investig Dermatol. 2015;135:1548–1555. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abram K, Silm H, Maaroos HI, Oona M. Risk factors associated with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:565–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choy MC, Visvanathan K, De Cruz P. An overview of the innate and adaptive immune system in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:2–13. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rana SV, Sharma S, Malik A, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and orocecal transit time in patients of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2594–2598. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castiglione F, Del Vecchio BG, Rispo A, et al. Orocecal transit time and bacterial overgrowth in patients with Crohn's disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:63–66. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200007000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kagnoff MF. Celiac disease: pathogenesis of a model immunogenetic disease. J Clin Investig. 2007;117:41–49. doi: 10.1172/JCI30253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krini M, Chouliaras G, Kanariou M, et al. HLA class II high-resolution genotyping in Greek children with celiac disease and impact on disease susceptibility. Pediatr Res. 2012;72:625–630. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodrigo L, Beteta-Gorriti V, Alvarez N, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal manifestations associated with celiac disease. Nutrients. 2018;10:800. doi: 10.3390/nu10070800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jabri B, Sollid LM. T cells in celiac disease. J Immunol. 2017;198:3005–3014. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liebregts T, Adam B, Bredack C, et al. Immune activation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:913–920. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Posserud I, Stotzer P-O, Björnsson ES, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2007;56:802–808. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.108712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rainer BM, Fischer AH, da Silva DLF, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea is associated with chronic systemic diseases in a skin severity-dependent manner: results of a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:604–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang JH, Luo JY, Dong L, Gong J, Tong M. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a general population-based study in Xi'an of northwest china. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1647–1651. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i11.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li S, Cho E, Drucker AM, Qureshi AA, Li W-Q. Alcohol intake and risk of rosacea in us women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.