Abstract

Efficient and novel recombinant protein expression systems can further reduce the production cost of enzymes. Vibrio natriegens is the fastest growing free-living bacterium with a doubling time of less than 10 min, which makes it highly attractive as a protein expression host. Here, 196 pET plasmids with different genes of interest (GOIs) were electroporated into the V. natriegens strain VnDX, which carries an integrated T7 RNA polymerase expression cassette. As a result, 65 and 75% of the tested GOIs obtained soluble expression in V. natriegens and Escherichia coli, respectively, 20 GOIs of which showed better expression in the former. Furthermore, we have adapted a consensus “what to try first” protocol for V. natriegens based on Terrific Broth medium. Six sampled GOIs encoding biocatalysts enzymes thus achieved 50–128% higher catalytic efficiency under the optimized expression conditions. Our study demonstrated V. natriegens as a pET-compatible expression host with a spectrum of highly expressed GOIs distinct from E. coli and an easy-to-use consensus protocol, solving the problem that some GOIs cannot be expressed well in E. coli.

Keywords: Vibrio natriegens, recombinant protein, pET expression system, fermentation optimization, synthetic biology

Introduction

The Escherichia coli pET expression system remains one of the most popular systems for recombinant protein production (Shilling et al., 2020). Numerous strategies have been proposed to improve recombinant protein production, including codon optimization of target proteins (Burgess-Brown et al., 2008; Menzella, 2011; Chung and Lee, 2012), screening and construction of a superior host cell (Choi et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015; Hayat et al., 2018), addition of fusion tags (Esposito and Chatterjee, 2006; Young et al., 2012; Hayat et al., 2018), optimization of expression elements (Gustafsson et al., 2012; Eichmann et al., 2019), or the development of high-density fermentation processes (Yee and Blanch, 1992; Zhang et al., 2000; Thongekkaew et al., 2008). Although E. coli is highly amenable to genetic modification and has a clear genetic background, quite many genes of interest (GOIs) were not well-expressed in E. coli. Furthermore, contamination of fermentation processes with other microorganisms or phages is a common problem that requires an urgent solution (Samson et al., 2013; Ou et al., 2020). Developing alternative hosts that possess a distinct spectrum of highly expressed GOIs complementary to E. coli and compatible with the pET expression system is an attractive way to solve this problem (Calero and Nikel, 2019).

Vibrio natriegens, a Gram-negative, non-pathogenic marine bacterium (Payne, 1958), is considered the fastest growing free-living bacterium, with a doubling time between 7 and 10 min under optimal conditions (Eagon, 1962; Weinstock et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2019). Estimates for the number of ribosomes in V. natriegens in the exponential phase suggest around 115,000 per cell, while E. coli is estimated to have only 70,000–90,000 (Des Soye et al., 2018), which partly explains its greater biomass synthesis rate and stronger protein expression ability (Zhu et al., 2020). Therefore, V. natriegens as the host for GOI expression is allowed to own higher productivity, saving time and energy costs in industrial production (Hoffart et al., 2017).

With the development of genetic tools or methods for V. natriegens since 2016 (Weinstock et al., 2016; Dalia et al., 2017), studies investigated multiple aspects of this organism, including fast growth and metabolism (Long et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2019; Pfeifer et al., 2019), expression of recombinant protein (Levarská et al., 2018; Becker et al., 2019; Eichmann et al., 2019; Tschirhart et al., 2019), establishment of cell-free protein synthesis system (CFPS) (Des Soye et al., 2018; Failmezger et al., 2018; Wiegand et al., 2018), and synthesis of chemicals (Liu, 2002; Fernandez-Llamosas et al., 2017; Ellis et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Erian et al., 2020). The T7 RNA polymerase cassette containing the gene encoding T7 RNA polymerase under the control of an isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) inducible promoter lacUV5 was necessary for pET protein expression system. The dns gene in V. natriegens encoding Dns nuclease reduces the integrity of plasmid DNA (Weinstock et al., 2016). Therefore, they developed the commercial V. natriegens Vmax strain by integrating the T7 RNA polymerase cassette at dns locus and successfully induced green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression using plasmid pET-28a-GFP (Weinstock et al., 2016). It has also been reported that isotopically labeled proteins FK506-binding protein (FKBP) and enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) (Becker et al., 2019), as well as recombinant human growth hormone (hGT), yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), and archaeal catalase-peroxidase (AfKatG) (Kormanova et al., 2020), were successfully produced using the pET expression system, among which FKBP, EYFP, and AfKatG showed better soluble expression than in E. coli BL21(DE3). Besides, the membrane protein Mrp from the secondary transport system of Vibrio cholerae was also functionally expressed in V. natriegens (Schleicher et al., 2018). However, despite its high application potential as a novel recombinant protein expression host, the recombinant GOI production capacity and highly expressed spectrum of V. natriegens have not been comprehensively evaluated.

Here, we electroporated each of 196 recombinant pET plasmids expressing commonly used biocatalysts enzymes (Jiang et al., 2016) into the non-pathogenic and fastest-growing V. natriegens ATCC14048 with an integrated T7 RNA polymerase cassette in advance. Analysis of the soluble expression of these GOIs in both V. natriegens VnDX and E. coli BL21(DE3) showed that the spectrum of highly expressed GOIs in V. natriegens was complementary to that of E. coli. Furthermore, we adapted a consensus “what to try first” fermentation protocol for V. natriegens based on Terrific Broth (TB) Salt (TBv2) medium. These findings confirm that V. natriegens has great potential as a novel cell factory for recombinant protein production, which is compatible with the pET system and complementary to E. coli.

Results

Evaluation of the Soluble Expression of 196 Genes of Interest and Analysis of the Spectrum of Highly Expressed Genes of Interest of V. natriegens

The T7 RNA polymerase cassette and spectinomycin resistance cassette used for positive screening were integrated into the dns locus in the genome of V. natriegens ATCC14048, resulting in a modified V. natriegens strain VnDX (Supplementary Figure 1). The pET-24a-GFP plasmid transformants of VnDX cultured under the same conditions as that of Vmax (Weinstock et al., 2016) resulted in similar GFP fluorescence (Supplementary Figure 1), indicating that the VnDX can be considered equivalent for recombinant protein production using the pET system to Vmax.

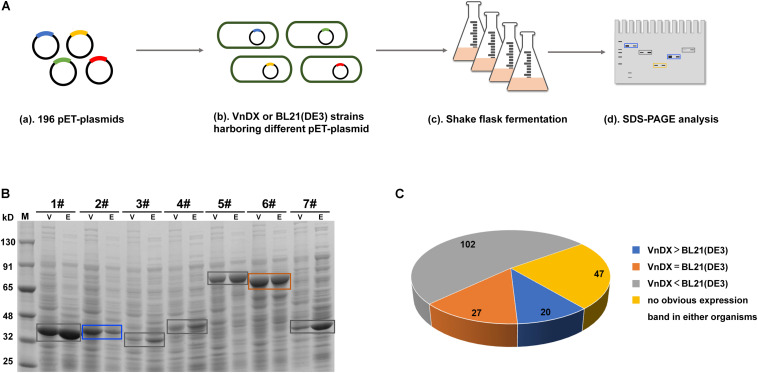

In a previous study, we established an enzyme library (Supplementary Table 1) containing 196 GOIs, including many commonly used biocatalyst enzymes (Jiang et al., 2016), the Saccharomyces cerevisiae sodium–potassium pump Trk1 (Ko and Gaber, 1991), and plant-derived isoprenoid synthase and its mutants (Yang et al., 2016), covering seven families of enzymes from bacteria, fungi, and plants. The pET expression plasmids encoding the GOIs were electroporated into V. natriegens VnDX and E. coli BL21(DE3) to compare the two expression systems. The optimal expression condition for E. coli BL21(DE3) (Sun et al., 2020) and the reported expression condition for V. natriegens (Weinstock et al., 2016) were used for flask fermentation to compare the soluble expression of each GOI in the two microbial hosts (Figure 1A). Finally, the quantitative amounts of the soluble protein per OD600 were compared between V. natriegens and E. coli (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Evaluation of the soluble expression of 196 genes of interest (GOIs) in Escherichia coli and Vibrio natriegens. (A) Flowchart about shake-flask fermentation of 196 GOIs and soluble expression comparison between E. coli BL21(DE3) and V. natriegens VnDX. (B) Compare the soluble expression of the same GOI in E. coli and V. natriegens through sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Here, 0.15 OD600 (10-well gel) or 0.075 OD600 (15-well gel) prepared crude protein samples were loaded to the corresponding protein gel wells. V, V. natriegens VnDX; E, E. coli BL21(DE3); Blue box, GOI possessing higher expression in VnDX than BL21(DE3); Orange box, GOI possessing the same expression in VnDX and BL21(DE3); Gray box, GOI possessing higher expression in BL21(DE3) than VnDX. 1#: Alanine racemase from Bacillus subtilis 168; 2#: N-acetyl amino acid racemase from Alcaligenes sp.; 3#: N-acetyl amino acid racemase from Deinococcus radiodurans NCHU1003; 4#: N-acetyl amino acid racemase from Amycolatopsis sp. TS-1-60; 5#: Maltooligosaccharide trehalose synthetase from Arthrobacter sp. Q36; 6#: Maltooligosaccharide trehalose synthetase from Arthrobacterium S34; 7#: D-carbamoylase (K34E) from Burkholderia pickettii. (C) Pie chart about the soluble expression results of 196 GOIs. VnDX > BL21(DE3): GOI possessing higher expression in VnDX than BL21(DE3); VnDX = BL21(DE3): GOI possessing the same expression in VnDX and BL21(DE3); VnDX < BL21(DE3): GOI possessing higher expression in BL21(DE3) than VnDX.

We evaluated the expression results of 196 GOIs (Figure 1C) and found that the expression of 102 GOIs in V. natriegens was not as good as in E. coli, while no significant overexpression bands were observed for 47 GOIs in either organism. However, we also found that 27 GOIs were expressed equally in both hosts, and 20 GOIs were expressed at higher levels than in E. coli (Figure 2A), unexpectedly, although the fermentation conditions of V. natriegens were not optimized.

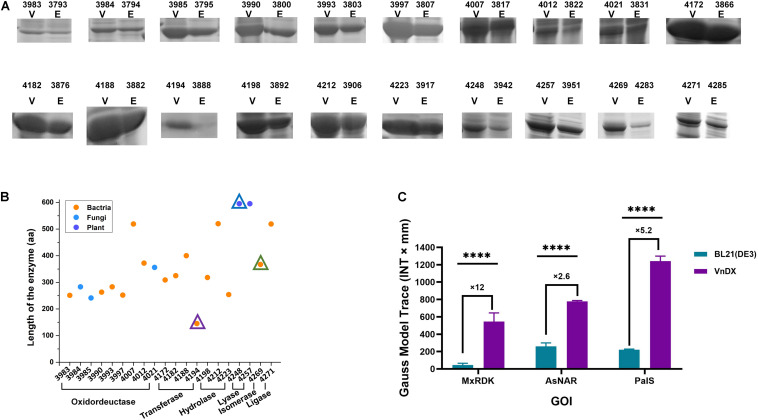

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of the spectrum of highly expressed genes of interest (GOIs) in V. natriegens VnDX. (A) Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) comparison of 20 highly expressed GOIs. Here, 0.15 OD600 (10-well gel) or 0.075 OD600 (15-well gel) prepared crude protein samples were loaded to the corresponding protein gel wells. V, V. natriegens VnDX; E, E. coli BL21(DE3). Numbers above the SDS-PAGE lanes represent strain numbers of 20 highly expressed GOIs in both hosts. The detailed information of these GOIs was marked with blue asterisk in Supplementary Table 3. (B) Classification, sources, and protein length analysis of 20 GOIs with high expression in V. natriegens. Numbers of horizontal axis represents V. natriegens strain numbers of 20 highly expressed GOIs. The GOI indicated by the three triangles corresponds to three enzymes in (C). (C) Quantity comparison of three highly expressed GOIs with poor expression in E. coli. MxRDK: Ribonucleoside diphosphate kinase from M. xanthus, CIBT3888 and CIBT4194; AsNAR: N-acetyl amino acid racemase from Alcaligenes sp. CIBT3942 and CIBT4248; PaIS: Isoprene synthase (K308R, C533W) from Populus alba (codon Optimized for E. coli) CIBT4283 and CIBT4269. Error bars represent the SD of n = 3 technical replicates. Quantitative analysis was calculated by software Quantity One 1-D; GraphPad Prism software was used to analyze the significance by t-test, ****P < 0.0001.

The 20 highly expressed GOIs of V. natriegens (Figure 2B) encompass 6 families of enzymes except for translocase (Supplementary Figure 3A), indicating that V. natriegens can express practically any type of enzyme. Analyzing the source of all GOIs revealed that the spectrum of highly expressed proteins of V. natriegens was derived from various species, including bacteria such as E. coli and Lactobacillus kefiri, fungi such as Candida magnoliae, and even plants (Populus alba) (Supplementary Figure 3B). The length of the 196 GOIs ranged from 100 to 1,000 amino acids (aa), while highly expressed GOIs in V. natriegens were all within 100–600 aa, suggesting that V. natriegens may have an advantage in the production of enzymes with small molecular weight (Supplementary Figure 3C).

Moreover, ribonucleoside diphosphate kinase from Myxococcus xanthus, N-acetyl amino acid racemase from Alcaligenes sp. and isoprene synthase (K308, C533W) from Populus alba (codon optimized for E. coli), showed poor expression in E. coli BL21(DE3) according to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), while having obvious soluble expression bands indicating excellent expression in V. natriegens. Further quantification revealed that the expression of N-acetyl amino acid racemase in V. natriegens was 2.6 times higher than that in E. coli, and that of isoprene synthase was 5.2 times higher. Ribonucleoside diphosphate kinase showed the most significant difference with 12 times higher expression in V. natriegens than in E. coli (Figure 2C). These three proteins are isomerase, lyase, and transferase, respectively. Moreover, they are derived from different species and have significantly different molecular weights. Thus, V. natriegens can be viewed as a complementary protein expression host to E. coli.

Our overall assessment indicates that the modified V. natriegens is compatible with the commonly used pET expression system and has a different spectrum of highly expressed GOIs from E. coli. Moreover, enzymes from all sources and all families can potentially be expressed using the pET system in V. natriegens. In addition, we also found that plant-derived enzymes were highly expressed in V. natriegens. Therefore, it can be used as a host for some GOIs that are difficult to express in E. coli, acting as a complementary expression host alongside E. coli.

Optimizing the Culture Medium for Growth and Protein Production

Because its enzyme activity can be measured conveniently (Sun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), we chose glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) from Bacillus subtilis as a reporter enzyme to screen culture media for optimal expression in V. natriegens. TB is the most recommended medium for protein production in E. coli (Gräslund et al., 2008; Novagen). Aiming to produce a better protein expression medium than the medium based on Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) and Luria–Bertani (LB) (Weinstock et al., 2016; Kormanova et al., 2020), an additional 15 g/L NaCl was added to TB (Hoffart et al., 2017), resulting in the modified TBv2 medium.

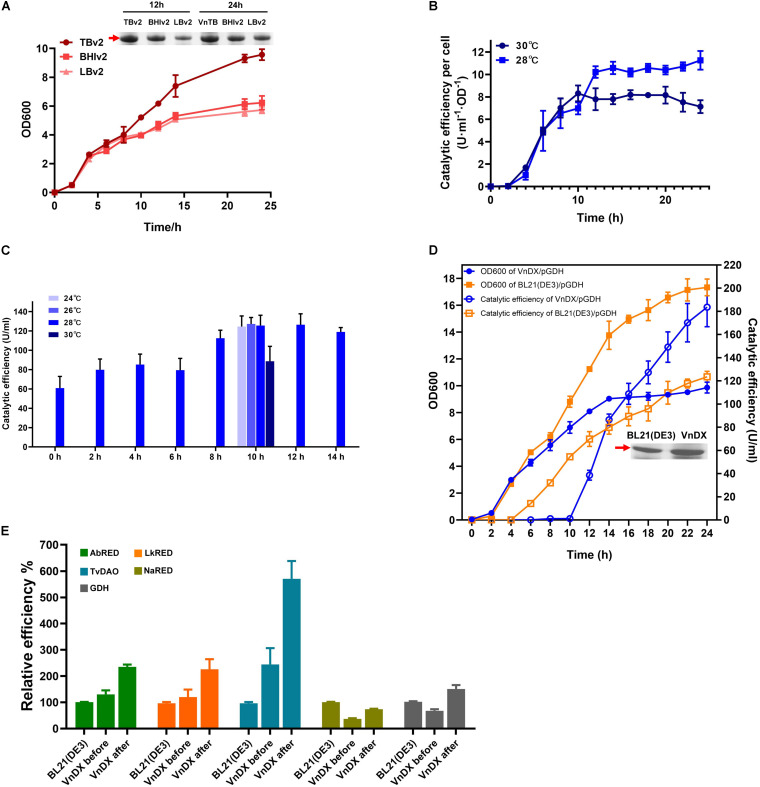

Growth of VnDX/pGDH was evaluated in BHIv2, TBv2, and LBv2 culture medium. There was no significant difference between the media during 0–8 h. However, the growth in TBv2 was much better than BHIv2 or LBv2 after 8 h. The final cell density in TBv2 was 50% higher than in BHIv2 and that in LBv2 was 16% lower than that in BHIv2. According to SDS-PAGE analysis, the GDH expression after 24-h fermentation in TBv2 was 59% higher than in BHIv2, while in LBv2, it was 48% lower than in BHIv2 (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Optimization of “what to try first” protocol for V. natriegens and testing the general applicability of the consensus protocol. (A) Growth curve of VnDX/pGDH in TBv2, BHIv2, and LBv2 medium and sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis of soluble glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) in 12 and 24 h. Here, 0.075 OD600 crude protein samples were loaded for SDS-PAGE. (B) The curve of GDH catalytic efficiency per OD600 [U/(ml⋅OD)] at 28 or 30°C. Induction occurred at 0 h. (C) Optimization of induction point and temperature of VnDX/pGDH. (D) Compare growth and catalytic efficiency of GDH between VnDX and BL21(DE3) under consensus “what to try first” fermentation conditions. (E) Five genes of interest (GOIs) were tested for the general applicability of the “what to try first” protocol. AbRED, carbonyl reductase from Acinetobacter baylyi CIBT3993; LkRED, carbonyl reductase from Lactobacillus kefiri CIBT3995; TvDAO, D-amino acid oxidase from Trigonopsis variabilis CIBT4021; NaRED, carbonyl reductase from Novosphingobium aromaticivorans DSM 12444 CIBT3990; GDH, glucose dehydrogenase from Bacillus subtilis. BL21(DE3), the optimal fermentation condition for E. coli BL21(DE3); VnDX before, V. natriegens fermentation condition before optimization; VnDX after, the fermentation condition using our improved “what to try first” protocol. Error bars represent the SD of n = 3 technical replicates.

To further verify whether TBv2 has generally better for recombinant protein production in V. natriegens, four enzymes were selected from the list of GOIs with poorer expression than E. coli: simvast acyltransferase from Aspergillus terreus, D-amino acid transaminase from Silicibacter promeroyi DSS-3, haine racemase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens str. C58, and maltooligosaccharide trehalose hydrolase from Arthrobacterium 34. In all cases, TBv2 was still the best medium for growth and protein expression (Supplementary Figure 4). Therefore, TBv2 can be generally recommended for protein production using the pET system in V. natriegens.

A Consensus “What to Try First” Protocol for Improving Catalytic Efficiency in V. natriegens

Kormanova et al. (2020) optimized the fermentation conditions for the expression of hGH, ADH, and AfkatG in V. natriegens, respectively, but obtained inconsistent results. Therefore, a more general protocol for V. natriegens was needed, giving researchers the first-to-try choice for protein production in this novel host. We aimed to adapt a consensus “what to try first” protocol in TBv2 for V. natriegens based on our collective analysis of the expression of over 200 GOIs in E. coli BL21(DE3) (Gräslund et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2016; Rongsheng et al., 2016).

When the induction temperature of VnDX/pGDH was decreased from 30 to 28°C, which was a “first-to-try” temperature for E. coli (Tao et al., 2014), the catalytic efficiency of GDH (U/ml) increased by 35% (Supplementary Figure 5B). This increase was not due to an increase in cell density (Supplementary Figure 5A) but resulted from an increase of GDH yield per OD600 by 57% (Figure 3B). We observed a turning point in catalytic efficiency per OD600 at nearly 10–12 h, so it was considered that adding an inducer at the 10th to the 12th hour might further increase GDH yield.

Therefore, we explored the optimal point in time to add the inducer after the seed culture was transferred to the shake flask (we called “induction point”). Eight trials were conducted, each being a multiple of two from 0 to 14 h, the highest titer of 130 U/ml was reached when it was induced at 10 h (Figure 3C). We then tested two other induction temperatures in the range of 24–30°C. The reduction of the temperature from 30 to 28°C did improve the GDH catalytic efficiency, but there was no obvious benefit from a further reduction of induction temperature (Figure 3C). Considering that the continuous reduction of temperature in industrial applications will greatly increase energy consumption, 28°C was selected as the “what to try first” induction temperature for V. natriegens.

The cell growth and catalytic efficiency of V. natriegens VnDX/pGDH and E. coli BL21(DE3)/pGDH were compared under the optimized “what to try first” conditions. Although the cell density of V. natriegens was 35% lower than that of E. coli at 24 h, the GDH yield of V. natriegens had overtaken that of E. coli after 4 h of induction. The catalytic efficiency reached 185 U/ml at the end of fermentation, which was 60% higher than that in E. coli (Figure 3D). Moreover, the yield per OD600 was 2.44 times higher than that of E. coli (Supplementary Figure 6), indicating that the higher catalytic efficiency of V. natriegens was due to superior expression of soluble GDH per unit of biomass. The possible explanation for this phenomenon was that the recombinant expression of toxic GDH in V. natriegens caused a greater burden on cells, so its growth rate was slightly lower than that under optimal conditions.

Our results indicate that choosing an appropriate induction temperature and induction point could balance cell growth and recombinant protein expression more effectively, which greatly enhanced the final catalytic efficiency of GDH.

Testing the General Applicability of the Consensus “What to Try First” Protocol

The GDH catalytic efficiency increased by 123% in V. natriegens using the “what to try first” protocol (Figure 3E). To further confirm this consensus protocol, we also tested the expression of carbonyl reductase from Acinetobacter baylyi (AbRED), carbonyl reductase from Lactobacillus kefiri (LkRED), and D-amino acid oxidase from Trigonopsis variabilis (TvDAO). These were chosen for convenience, since their enzyme activity assays were the simplest among the 20 enzymes that showed better expression in V. natriegens than in E. coli. Additionally, we also tested carbonyl reductase from Novosphingobium aromaticivorans DSM 12444 (NaRED), which showed inferior expression in V. natriegens. Compared with the fermentation conditions reported in the literature, the enzyme efficiency increased by 82% for LkRED, 76% for AbRED, 128% for TvDAO, and 100% for NaRED. Furthermore, while the NaRED efficiency in V. natriegens was only 33% of that in E. coli before optimization, it increased to 60% under the optimized conditions (Figure 3E).

Thus, to adapt the E. coli consensus “what to try first” protocol based on TBv2 medium for V. natriegens, we changed the temperature to optimally grown temperature 30°C (Supplementary Figure 7) and induction point to the 10th hour at 28°C for V. natriegens in this study, and we proved that this modified protocol was effective for various GOIs.

Discussion

This study compared the soluble expression of 196 GOI encoding enzymes of various families from various sources between V. natriegens VnDX and E. coli BL21(DE3). The results showed that the engineered V. natriegens strain VnDX is compatible with the pET system but had a distinct spectrum of highly expressed proteins compared with E. coli, indicating that it might be a valuable complementary expression system to E. coli. A consensus “what to try first” protocol for V. natriegens was obtained through fermentation optimization, which significantly improved the expression of GDH, TvDAO, NaRED, LkRED, and AbRED. Moreover, this protocol also enabled the soluble expression of other recombinant GOIs in V. natriegens, indicating its general applicability.

While comparison of the insoluble or total expression should give us an in-depth insight into the capacity of protein synthesis in both E. coli and V. natriegens, our limited resources were allocated to evaluation of the soluble protein output from more GOIs in V. natriegens rather than the total recombinant protein yield in both hosts. Nevertheless, the insoluble fractions of three GOIs in both organisms were run on SDS-PAGE and the amount of recombinant protein looked negligible (Supplementary Figure 8). The success rate of soluble expression was 75% in E. coli, while it reached 65% in V. natriegens. The soluble expression of 129 GOIs in V. natriegens was less than or equal to that of E. coli. There are three possible explanations for this phenomenon: (1) Almost all the GOIs were codon-optimized for E. coli. While GOIs codon-optimized for V. natriegens and E. coli, respectively, should avoid biases, considering that E. coli is the first-to-try chassis for protein expression, it will save time and cost in practice to transform pET plasmids that were not well-expressed in E. coli into V. natriegens directly. For the researchers who are dedicated to optimize their GOI expression in V. natriegens or believe V. natriegens is the better expression host at the beginning, they had better synthesize their GOIs with V. natriegens codon optimization. (2) The spectrum of highly expressed was different in V. natriegens and E. coli. Therefore, the two hosts are compatible. (3) E. coli BL21(DE3) produced proteins under optimized fermentation conditions, while V. natriegens used suboptimal conditions and our consensus “what to try first” protocol increased the yield for many GOIs. Therefore, further optimization should be considered when using V. natriegens as an industrial expression host in the future.

It is known that differences in media composition affect microbial recombinant protein production (Broedel et al., 2001; Terol et al., 2019). Furthermore, it was reported that the stability of expression plasmids could be improved by using complex nitrogen sources (Matsui et al., 1990). Here, we reported TBv2 for the first time, a medium recommended for V. natriegens fermentation. We believe that several factors contribute to the satisfactory results of protein production in TBv2: its carbon source was more abundant than those of LBv2 and BHIv2; a higher concentration of yeast extract increased background expression of lacUV5 promoter (Doran et al., 1990; Gomes and Mergulhao, 2017), which may improve the protein expression of the T7 system; TBv2 contains glycerin (Clomburg and Gonzalez, 2013; Terol et al., 2019), and supplementing complex media with glycerol improves protein production (Terol et al., 2019).

Maximization of protein production and minimization of costs are major aims in the production of recombinant proteins, which requires a balance between cell growth and the expression of recombinant proteins (Gomes and Mergulhao, 2017). It has been reported that de-coupling cell growth from protein production in E. coli could increase the yield of various proteins (Lemmerer et al., 2019; Stargardt et al., 2020). We found that the accumulation of biomass at the optimal temperature in the early fermentation stage and induction of protein expression in the later stage were also effective strategies to improve the yield of recombinant proteins in V. natriegens. These results showed that appropriate separation between the growth of V. natriegens and protein production could better balance the resources in the cell and achieve the goal of maximizing protein production.

Because different proteins had different optimal expression conditions, there can be no “right” answer a priori (Gräslund et al., 2008), which is the same in V. natriegens (Kormanova et al., 2020). In order to facilitate the decision-making, we compared with the general fermentation method for E. coli established in our laboratory (Jiang et al., 2016), proposed a consensus “what to try first” protocol for V. natriegens and verified the effectiveness of this protocol in the expression of multiple GOIs. This protocol provides a reference for researchers who are starting out with protein expression in V. natriegens. When they are uncertain about appropriate fermentation conditions for a protein, they can try our tested condition first.

Our study focused on increasing the total amount of recombinant protein by enhancing the protein production per cell. Although the enzyme catalytic efficiency of several proteins was significantly higher than that in E. coli, it was also found that the shake-flask fermentation density of V. natriegens was 25% lower than that of E. coli, representing a possible bottleneck for industrial application. To solve the problem of low fermentation density, optimization can conceivably proceed in two aspects: (1) Vibrio sp. produce more extracellular polysaccharide and capsular polysaccharide than E. coli (Teschler et al., 2015). As a result, carbon sources are used for polysaccharide synthesis, which results in the cells being coated with capsular polysaccharides or biofilms, and the amount of extracellular polysaccharides in the fermentation broth increases (Flemming and Wingender, 2010). Blocking the polysaccharide synthesis pathway can redirect more carbon flux toward biomass accumulation and protein synthesis, and knocking out the polysaccharide synthesis pathway can also theoretically reduce the viscosity of the fermentation medium, thereby improving the mass transfer efficiency. (2) Knocking out the quorum-sensing system of V. natriegens may also increase the maximal cell density of the microbial population (Marrs and Swalla, 2008). The competitiveness of the V. natriegens protein expression system will be greatly improved if the number of cells per unit volume could be increased.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that V. natriegens is an effective pET-based expression host complementary to E. coli. We hope that these findings will inspire more researchers to introduce their pET plasmids with poor expression in E. coli into V. natriegens. Furthermore, a consensus “what to try first” protocol was proposed to further enhance the protein production in V. natriegens, as well as providing guidance to researchers interested in V. natriegens. Finally, we also hope to inspire other researchers to further optimize this new bacterial chassis to make it much more competitive for recombinant protein expression.

Materials and Methods

Construction of Plasmids and Strains

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supporting information Supplementary Table 2, and the primers were listed in Supplementary Table 4.

All restriction enzymes used in this study were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, United States). The PrimeSTAR Max® (DNA polymerase TaKaRa, China) and 2 × Rapid Taq Master Mix (Vazyme, China) were used for gene cloning and colony PCR, respectively.

The plasmid pMD19T-dnsaLR-T7RNApol was cloned in two steps: (1) The pMD19T vector was linearized by XbaI digestion. The spectinomycin cassette was cloned from pTargetF, and the 3-kb homologous arms were cloned from the genome of Vibrio natriegens ATCC14048. These three fragments were assembled with the linearized pMD19T by Gibson Assembly, yielding pMD19T-dnsaLR-spec. (2) The pMD19T-dnsaLR-spec plasmid was further digested with HindIII, and the larger DNA fragment was extracted using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit. The T7 RNA polymerase cassette was cloned from the genome of E. coli BL21(DE3), and the spectinomycin cassette was cloned from pMD19T-dnsaLR-spec. The three fragments were assembled by Gibson Assembly (Gibson et al., 2009), resulting in the plasmid pMD19T-dnsaLR-T7RNApol.

Plasmids were constructed and propagated in E. coli DH5α, purified using Miniprep Kits (Qiagen, Germany), and verified by Sanger sequencing (TsingKe, China). The plasmid pMD19T-dnsaLR-T7RNApol was then digested with XbaI, yielding the linearized DNA fragments dnsaLR-T7RNApol, which was used for further natural transformation. The V. natriegens strain VnDX, which was derived from ATCC 14048 by integrating the T7 RNA polymerase expression cassette at the dns locus, was constructed using MuGENT method (Dalia et al., 2017). Plasmids were transferred into V. natriegens using a previously published electroporation protocol (Weinstock et al., 2016).

Media and Culture Conditions

The E. coli strains were grown in LB or TB medium at 37°C, supplemented where necessary with 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Amp) or 100 μg/ml kanamycin (StateKan). The V. natriegens strains were grown in LBv2, BHIv2 (Weinstock et al., 2016), or TBv2 medium (12 g/L tryptone, 24 g/L yeast extract, 0.5% v/v glycerol, 15 g/L NaCl, 2.31 g/L KH2PO4, 16.43 g/L K2HPO4⋅3H2O) medium at 30°C. Where needed, 15 g/L agar added to produce solid medium. Plasmids encoding TfoX were maintained in V. natriegens by adding 100 μg/ml carbenicillin (Carb). V. natriegens strains maintaining pET plasmids were supplied with 100 μg/ml Carb or 200 μg/ml StateKan.

Shake-Flask Fermentation

V. natriegens strains harboring pET plasmids were grown in 5 ml of LBv2 liquid medium overnight at 30°C. Then, 300 μl of the resulting seed cultures were used to inoculate 30 ml of BHIv2 medium in 250-ml shake flasks. IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.3 mM when seed cultures were inoculated, and fermentation was allowed to continue for an additional 22 h at 30°C.

E. coli strains harboring pET plasmids were grown in 5 ml of LB liquid medium overnight at 37°C. Then, 300 μl of the resulting seed cultures were used to inoculate 30 ml of TB medium in 250-ml shake flasks. Cells were cultured at 37°C to an OD600 of 2–4 (nearly 3 h), at which point IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.3 mM, and the fermentation was allowed to continue at 28°C for an additional 22 h. The fermentation conditions for E. coli BL21(DE3) used in this study were optimized by our laboratory in earlier work (Sun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020).

After 22-h fermentation, the cell density was measured by spectrophotometer at 600 nm. Then, 1 ml final fermentation culture was collected in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes, respectively, for subsequent protein expression analysis.

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis Analysis

The collected 1-ml sample of the fermentation broth was centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 rpm, and the supernatant was removed. The cells were resuspended in 1 ml of 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and lysed using an Ultrasonic Cell Disruptor (operating for 5 s, pausing for 5 s, 40 times). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 4°C, 12,000 rpm for 10 min to remove the cell debris. Eighty microliters of the supernatant was mixed with 20 μl of 5 × SDS-PAGE loading buffer and heated to 100°C in a metal block for 10 min. The final protein samples were used for SDS-PAGE (WSHT, China).

To facilitate the gel analysis, we calculated normalized loading volumes for standard gels (Novagen). Samples containing the protein from an amount of cells corresponding to 0.15 OD600 units (10-well gel) or 0.075 OD600 units (15-well gel) were added to the corresponding protein gel wells and separated at 90 V until the dye reached at the end of the gel. Quantitative comparison was conducted using Quantity One 1-D software (BioRad, United States) and Quantity One User Guide for Version 4.6.2. According to the calculation results of Quantity One, NVn represents the value of the GOI overexpression band in VnDX, and NEc represents the value of the GOI overexpression band in BL21(DE3). VnDX = BL21(DE3) when the following inequality is satisfied. GraphPad prism software was used for statistical analysis of data.

Glucose Dehydrogenase Activity Assay

To measure GDH activity, 1 ml of fermentation broth was treated as described above, and the resulting supernatant was the crude enzyme solution. The reaction mixture contained 100 mM glucose, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM NAD+, and the diluted crude enzyme solution. The GDH activity was assayed at 30°C by following the increase of the absorbance at 340 nm (A340) due to the reduction of NAD+ to NADH. The enzyme activity was calculated using the formula U/ml = [ΔA/min] × [1/ε] × 8,000 [ε = A/cL = 6.402 ml/(μmol × cm)] (Bucher et al., 1974).

Carbonyl Reductase Activity Assay

To measure carbonyl reductase activity, 1 ml of fermentation broth was treated as described above, and the resulting supernatant was the crude enzyme solution. The reaction mixture contained 16 g/L isopropanol, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM NAD+, and the diluted crude enzyme solution. The carbonyl reductase activity was assayed at 37°C by following the increase ofA340. The enzyme activity was calculated using the formula U/ml = [ΔA/min] × [1/ε] × 8,000 [ε = A/cL = 6.402 ml/(μmol × cm)] (Bucher et al., 1974).

D-Amino Acid Oxidase Activity Assay

To measure D-amino acid oxidase activity, 1 ml of fermentation broth was treated as described above, and the resulting supernatant was the crude enzyme solution. Then, 0.1 ml of the diluted crude enzyme was pipetted into a 1.5 cm × 15 cm test tube, and 400 IU of catalase (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 ml 0.1 M D-alanine [prepared with 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 8.0, Sangon Biotech, China] were added. The mixed solution was placed in a water bath at 37°C and shaken at 180 rpm for 10 min. Then, 0.6 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid (Aladdin, China) was added to terminate the reaction and 0.1 ml of the mixed solution was diluted with 0.9 ml PBS, followed by the addition of 0.4 ml of 0.2% 2.4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (Aladdin, China) and incubation for 10 min at room temperature (RT). Then, 1.5 ml 3 M NaOH (Sangon Biotech, China) was added, mixed well, and incubated for 15 min at RT. The mixture was then centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was taken to measure the absorbance at 550 nm (Zheng et al., 2007). One unit (U) of DAAO enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce 1 μmol of sodium pyruvate per minute.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

JX, FD, JY, YJ, and SY developed the research plan. JX, FD, and MW performed the experiments. JX and RT collected and analyzed data. JX, JY, MW, YJ, SY, and LY wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

RT was employed by company Huzhou Yisheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. YJ was employed by company Shanghai Taoyusheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ankur B. Dalia from Indiana University for providing the pMMB67EH-tfox plasmid.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Numbers: 21825804 and 31921006), the Special Program for Biological Sciences Research of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KFJ-BRP-009) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (18ZR1446500).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.627181/full#supplementary-material

Construction of V. natriegens VnDX strain and GFP expression using pET-based system. (A) Schematic of the construction of VnDX. The T7 RNA polymerase and specR cassettes were integrated into the dns locus using natural transformation (MuGNET described in section “Materials and Methods”). tDNA, transformed DNA. (B) plasmid pET-24a-GFP was transformed into VnDX and BL21(DE3), respectively, and GFP fluorescence was detected with or without IPTG in liquid medium. Top: cells under white light; bottom: cells under blue light. VnDX or BL21(DE3) strain containing pET-24a-GFP showed visible GFP fluorescence after IPTG induction. (C) GFP fluorescence was detected with or without IPTG on LBv2 agar plate. Top: cells under white light; bottom: cells under blue light. 1#: V. natriegens/pET-24a; 2#: VnDX/pET-24a; 3#: V. natriegens/pET-24a-GFP; 4#: VnDX/pET-24a-GFP; 5#: BL21(DE3)/pET-24a-GFP. Only V. natriegens strain with T7 RNA polymerase cassette and pET-24a-GFP showed GFP fluorescence after IPTG induction. (D) SDS–PAGE analysis of soluble cytosolic fraction of lysed cells (the GFP band is marked with a red arrow).

Comparison the soluble expression of 196 GOI in our library according to SDS-PAGE. (A–T) 0.15 OD (10-well gel) or 0.075 OD (15-well gel) prepared crude protein samples were loaded to the corresponding protein gel wells. V, V. natriegens VnDX; E, E. coli BL21(DE3); Ctrl, Glucose dehydrogenase from Bacillus subtillis contained in each batch of fermentation as a positive control; Blue box, GOI possessing higher expression in VnDX than BL21(DE3); Orange box, GOI possessing the same expression in VnDX and BL21(DE3); Gray box, GOI possessing higher expression in BL21(DE3) than VnDX. Numbers above the lanes represent V. natriegens or E. coli strains and the detailed information of these strains were shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Classifications of the evaluation results of these 196 GOI in VnDX and BL21(DE3) according to enzyme families, sources and lengths of amino acids. (A) Classification according to enzyme family. (B) Classification according to enzyme sources. (C) Classification according to the length of enzymes. VnDX>BL21(DE3): GOI possessing higher expression in VnDX than BL21(DE3); VnDX=BL21(DE3): GOI possessing the same expression in VnDX and BL21(DE3); VnDX<BL21(DE3): GOI possessing higher expression in BL21(DE3) than VnDX.

Growth curve and protein expressions of four GOI in BHIv2, TBv2, and LBv2 culture medium. (A) Simvast acyltransferase from Aspergillus terreus. (B) D-amino acid transaminase from Silicibacter promeroyi DSS-3. (C) Haine racemase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens str. C58. (D) Maltooligosaccharide trehalose hydrolase from Arthrobacterium S 34. 0.15 OD600 (10-well gel) prepared crude protein samples were loaded to the corresponding protein gel wells. Error bars represent the SD of n = 3 technical replicates.

The growth and GDH catalytic efficiency curve of VnDX/pGDH at 30 or 28°C. (A) the growth curve of VnDX/pGDH at 30 or 28°C. (B) the GDH catalytic efficiency (U/ml) curve of VnDX/pGDH at 30 or 28°C. Error bars represent the SD of n = 3 technical replicates.

The GDH catalytic efficiency per OD600 (U⋅ml–1⋅OD–1) in BL21(DE3)/pGDH and VnDX/pGDH at the end of fermentation (24 h). Error bars represent the SD of n = 3 technical replicates.

The growth curve of V. natriegens at 37 or 30°C. Error bars represent the SD of n = 3 technical replicates.

The SDS-PAGE of soluble and insoluble expression of 3 GOI. 0.15 OD600 prepared crude protein samples were loaded to the corresponding protein gel wells. V, V. natriegens VnDX; E, E. coli BL21(DE3); Sol, soluble expression proteins; Insol, insoluble expression proteins. The GOI band is marked with red arrows. The detailed information of these GOI were shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Enzyme classification of 196 GOI in our library.

Strains and plasmids used in this work.

Detailed information of 196 GOI in E. coli and V. natriegens.

Primers used in this study.

References

- Becker W., Wimberger F., Zangger K. (2019). Vibrio natriegens: an alternative expression system for the high-yield production of isotopically labeled proteins. Biochemistry 58 2799–2803. 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broedel S. J., Papciak S., Jones W. (2001). The selection of optimum media formulations for improved expression of recombinant proteins in E. coli. Technic. Bull. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher T., Krell H., Lusch G. (1974). Molar extinction coefficients of NADH and NADPH at Hg spectral lines. Z. Klin. Chem. Klin. Biochem. 12 239–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess-Brown N. A., Sharma S., Sobott F., Loenarz C., Oppermann U., Gileadi O. (2008). Codon optimization can improve expression of human genes in Escherichia coli: a multi-gene study. Protein Expr. Purif. 59 94–102. 10.1016/j.pep.2008.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calero P., Nikel P. I. (2019). Chasing bacterial chassis for metabolic engineering: a perspective review from classical to non-traditional microorganisms. Microb. Biotechnol. 12 98–124. 10.1111/1751-7915.13292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. W., Yim S. S., Kim M. J., Jeong K. J. (2015). Enhanced production of recombinant proteins with Corynebacterium glutamicum by deletion of insertion sequences (IS elements). Microb. Cell. Fact. 14:205. 10.1186/s12934-015-0401-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K. S., Lee D.-Y. (2012). Computational codon optimization of synthetic gene for protein expression. BMC Syst. Biol. 6:134. 10.1186/1752-0509-6-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clomburg J. M., Gonzalez R. (2013). Anaerobic fermentation of glycerol: a platform for renewable fuels and chemicals. Trends Biotechnol. 31 20–28. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalia T. N., Hayes C. A., Stolyar S., Marx C. J., McKinlay J. B., Dalia A. B. (2017). Multiplex genome editing by natural transformation (MuGENT) for synthetic biology in Vibrio natriegens. ACS Synth. Biol. 15 1650–1655. 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Soye B. J., Davidson S. R., Weinstock M. T., Gibson D. G., Jewett M. C. (2018). Establishing a high-yielding cell-free protein synthesis platform derived from Vibrio natriegens. ACS Synth. Biol. 7 2245–2255. 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran J. L., Leskiw B. K., Petrich A. K., Westlake D. W. S., Jensen S. E. (1990). Production of streptomyces clavuligerus isopenicillin N synthase in Escherichia coli using two-cistron expression systems. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 5 197–206. 10.1007/BF01569677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagon R. G. (1962). Pseudomonas natriegens, a marine bacterium with a generation time of less than 10 minutes. J. Bacteriol. 83 736–737. 10.1128/JB.83.4.736-737.1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichmann J., Oberpaul M., Weidner T., Gerlach D., Czermak P. (2019). Selection of high producers from combinatorial libraries for the production of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli and Vibrio natriegens. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7:254. 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis G. A., Tschirhart T., Spangler J., Walper S. A., Medintz placeI. L., Vora G. J. (2019). Exploiting the feedstock flexibility of the emergent synthetic biology chassis Vibrio natriegens for engineered natural product production. Mar. Drugs 17:679. 10.3390/md17120679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erian A. M., Freitag P., Gibisch M., Pflügl S. (2020). High rate 2,3-butanediol production with Vibrio natriegens. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 10:100408. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito D., Chatterjee D. K. (2006). Enhancement of soluble protein expression through the use of fusion tags. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17 353–358. 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Failmezger J., Scholz S., Blombach B., Siemann-Herzberg M. (2018). Cell-free protein synthesis from fast-growing Vibrio natriegens. Front. Microbiol. 9:1146. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Llamosas H., Castro L., Blazquez M. L., Diaz E., Carmona M. (2017). Speeding up bioproduction of selenium nanoparticles by using Vibrio natriegens as microbial factory. Sci. Rep. 7:16046. 10.1038/s41598-017-16252-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming H. C., Wingender J. J. N. R. M. (2010). The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8 623–633. 10.1038/nrmicro2415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson D. G., Young L., Chuang R. Y., Venter J. C., Hutchison C. A., III, Smith H. O. (2009). Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 6 343–345. 10.1038/nmeth.1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes L. C., Mergulhao F. J. (2017). Effects of antibiotic concentration and nutrient medium composition on Escherichia coli biofilm formation and green fluorescent protein expression. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 364:8. 10.1093/femsle/fnx042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gräslund S., Nordlund P., Weigelt J., Hallberg B. M., Bray J., Gileadi O., et al. (2008). Protein production and purification. Nat. Methods 5 135–146. 10.1038/nmeth.f.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson C., Minshull J., Govindarajan S., placeNess J., Villalobos A., Welch M. (2012). Engineering genes for predictable protein expression. Protein Expr. Purif. 83 37–46. 10.1016/j.pep.2012.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat S. M. G., Farahani N., Golichenari B., Sahebkar A. (2018). Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli (E.coli): what we need to know. Curr. Pharm. Des. 24 718–725. 10.2174/1381612824666180131121940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffart E., Grenz S., Lange J., Nitschel R., Muller F., Schwentner A., et al. (2017). High substrate uptake rates empower Vibrio natriegens as production host for industrial biotechnology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83:AEM.1614-17. 10.1128/AEM.01614-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Tao R., Yang S. (2016). Tailor-made biocatalysts enzymes for the fine chemical industry in China. Biotechnol. J. 11 1121–1123. 10.1002/biot.201500682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko C. H., Gaber R. F. (1991). Trk1 and trk2 encode structurally related K+ transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11 4266–4273. 10.1128/mcb.11.8.4266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kormanova L., Rybecka S., Levarski Z., Struharnanska E., Levarska L., Blasko J., et al. (2020). Comparison of simple expression procedures in novel expression host Vibrio natriegens and established Escherichia coli system. J. Biotechnol. 321 57–67. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. H., Ostrov N., Wong B. G., Gold M. A., Khalil A. S., Church G. M. (2019). Functional genomics of the rapidly replicating bacterium Vibrio natriegens by CRISPRi. Nat. Microbiol. 4 1105–1113. 10.1038/s41564-019-0423-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmerer M., Mairhofer J., Lepak A., Longus K., Hahn R., Nidetzky B. (2019). Decoupling of recombinant protein production from Escherichia coli cell growth enhances functional expression of plant Leloir glycosyltransferases. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 116 1259–1268. 10.1002/bit.26934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levarská L., Levarski Z., Stuchlík S., Kormanová L., Turna J. (2018). Vibrio natriegens – an effective tool for protein production. New Biotechnol. 44:S77. [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Feng X., Ding Y., Zhao G., Liu H., Xian M. (2015). Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli to improve recombinant protein production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99 10367–10377. 10.1007/s00253-015-6955-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.-J. (2002). Biosynthesis and accumulation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) in Vibrio natriegens. Sheng wu gong cheng xue bao 18 614–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long C. P., Gonzalez J. E., Cipolla R. M., Antoniewicz M. R. (2017). Metabolism of the fast-growing bacterium Vibrio natriegens elucidated by 13C metabolic flux analysis. Metab. placecountry-regionEng. 44 191–197. 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs B., Swalla B. M. (2008). New[[AQ23]] genetically modified microorganism comprises a genetic mutation, where the mutation confers upon the genetically modified microorganism the ability to grow to a greater cell density, useful for producing a fermentation product. Patent. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T., Sato H., Sato S., Mukataka S., Takahashi J. J. A. (1990). Effects of nutritional conditions on plasmid stability and production of tryptophan synthase by a recombinant Escherichia coli. Agr. Biol. Chem. 54 619–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzella H. G. (2011). Comparison of two codon optimization strategies to enhance recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli. Microb. Cell Fact. 10:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou X., Peng F., Wu X., Xu P., Zong M., Lou W. (2020). Efficient protein expression in a robust Escherichia coli strain and its application for kinetic resolution of racemic glycidyl o-methylphenyl ether in high concentration. Biochem. Eng. J. 158:107573. 10.1016/j.bej.2020.107573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Payne W. J. (1958). studies on bacterial utilization of uronic acids. J. Bacteriol. 76 301–307. 10.1128/JB.76.3.301-307.1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer E., Michniewski S., Gätgens C., Münch E., Müller F., Polen T., et al. (2019). Generation of a prophage-free variant of the fast-growing bacterium Vibrio natriegens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85:e00853-19. 10.1128/AEM.00853-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rongsheng T., Wenchao F., Fuyun Z., Benben Y., Weihong J., Yunliu Y., et al. (2016). Development and case study of biocatalysis based green chemistry in fine chemical manufacture. J. Shanghai Institute Technol. (Natural Science) 16 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Samson J. E., Magadán A. H., Sabri M., Moineau S. (2013). Revenge of the phages: defeating bacterial defences. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11 675–687. 10.1038/nrmicro3096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher L., Muras V., Claussen B., Pfannstiel J., Blombach B., Dibrov P., et al. (2018). Vibrio natriegens as host for expression of multisubunit membrane protein complexes. Front. Microbiol. 9:2537. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilling P. J., Mirzadeh K., Cumming A. J., Widesheim M., Köck Z., Daley D. O. (2020). Improved designs for pET expression plasmids increase protein production yield in Escherichia coli. Commun. Biol. 3:214. 10.1038/s42003-020-0939-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stargardt P., Feuchtenhofer L., Cserjan-Puschmann M., Striedner G., Mairhofer J. (2020). Bacteriophage inspired growth-decoupled recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 9 1336–1348. 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.-M., Zhang Z.-X., Wang L.-R., Wang J.-G., Liang Y., Yang H.-F., et al. (2020). Downregulation of T7 RNA polymerase transcription enhances pET-based recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) by suppressing autolysis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 118 153–163. 10.1002/bit.27558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R., Jiang Y., Zhu F., Yang S. (2014). A one-pot system for production of L-2-aminobutyric acid from L-threonine by L-threonine deaminase and a NADH-regeneration system based on L-leucine dehydrogenase and formate dehydrogenase. Biotechnol. Lett. 36 835–841. 10.1007/s10529-013-1424-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terol G. L., Gallego-Jara J., Sola Martinez R. A., Diaz M. C., Puente T. D. D. (2019). Engineering protein production by rationally choosing a carbon and nitrogen source using E. coli BL21 acetate metabolism knockout strains. Microb. Cell Fact 18:151. 10.1186/s12934-019-1202-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teschler J. K., Zamorano-Sanchez D., Utada A. S., Warner C. J., Wong G. C., Linington R. G., et al. (2015). Living in the matrix: assembly and control of Vibrio cholerae biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13 255–268. 10.1038/nrmicro3433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thongekkaew J., Ikeda H., Masaki K., Iefuji H. (2008). An acidic and thermostable carboxymethyl cellulase from the yeast Cryptococcus sp. S-2: purification, characterization and improvement of its recombinant enzyme production by high cell-density fermentation of Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr. Purif. 60 140–146. 10.1016/j.pep.2008.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschirhart T., Shukla V., Kelly E. E., Schultzhaus Z., NewRingeisen E., Erickson J. S., et al. (2019). Synthetic biology tools for the fast-growing marine bacterium Vibrio natriegens. ACS Synth. Biol. 8 2069–2079. 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Tschirhart T., Schultzhaus Z., Kelly E. E., Chen A., Oh E., et al. (2019). Melanin produced by the fast-growing marine bacterium Vibrio natriegens through heterologous biosynthesis: characterization and application. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86 e02749-19. 10.1128/aem.02749-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock M. T., Hesek E. D., Wilson C. M., Gibson D. G. (2016). Vibrio natriegens as a fast-growing host for molecular biology. Nat. Methods 13 849–851. 10.1038/nmeth.3970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand D. J., Lee H. H., Ostrov N., Church G. M. (2018). Establishing a cell-free Vibrio natriegens expression system. ACS Synth. Biol. 7 2475–2479. 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Gao X., Jiang Y., Sun B., Gao F., Yang S. (2016). Synergy between methylerythritol phosphate pathway and mevalonate pathway for isoprene production in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 37 79–91. 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee L., Blanch H. W. (1992). Recombinant protein expression in high cell density fed-batch cultures of Escherichia coli. Biotechnology (N Y) 10 1550–1556. 10.1038/nbt1292-1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young C. L., Britton Z. T., Robinson A. S. (2012). Recombinant protein expression and purification: a comprehensive review of affinity tags and microbial applications. Biotechnol. J. 7 620–634. 10.1002/biot.201100155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Inan M., Meagher M. M. (2000). Fermentation strategies for recombinant protein expression in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol. Bioprocess placecountry-regionEng. 5 275–287. 10.1007/BF02942184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Sun X., Wang Q., Xu J., Dong F., Yang S., et al. (2020). Multicopy chromosomal integration using CRISPR-associated transposases. ACS Synth. Biol. 9 1998–2008. 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H., Zhu T., Chen J., Zhao Y., Jiang W., Zhao G., et al. (2007). Construction of recombinant Escherichia coli D11/pMSTO and its use in enzymatic preparation of 7-aminocephalosporanic acid in one pot. J. Biotechnol. 3 400–405. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M., Mu H., Jia M., Deng L., Dai X. (2020). Control of ribosome synthesis in bacteria: the important role of rRNA chain elongation rate. Sci. China Life Sci. 10.1007/s11427-020-1742-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Construction of V. natriegens VnDX strain and GFP expression using pET-based system. (A) Schematic of the construction of VnDX. The T7 RNA polymerase and specR cassettes were integrated into the dns locus using natural transformation (MuGNET described in section “Materials and Methods”). tDNA, transformed DNA. (B) plasmid pET-24a-GFP was transformed into VnDX and BL21(DE3), respectively, and GFP fluorescence was detected with or without IPTG in liquid medium. Top: cells under white light; bottom: cells under blue light. VnDX or BL21(DE3) strain containing pET-24a-GFP showed visible GFP fluorescence after IPTG induction. (C) GFP fluorescence was detected with or without IPTG on LBv2 agar plate. Top: cells under white light; bottom: cells under blue light. 1#: V. natriegens/pET-24a; 2#: VnDX/pET-24a; 3#: V. natriegens/pET-24a-GFP; 4#: VnDX/pET-24a-GFP; 5#: BL21(DE3)/pET-24a-GFP. Only V. natriegens strain with T7 RNA polymerase cassette and pET-24a-GFP showed GFP fluorescence after IPTG induction. (D) SDS–PAGE analysis of soluble cytosolic fraction of lysed cells (the GFP band is marked with a red arrow).

Comparison the soluble expression of 196 GOI in our library according to SDS-PAGE. (A–T) 0.15 OD (10-well gel) or 0.075 OD (15-well gel) prepared crude protein samples were loaded to the corresponding protein gel wells. V, V. natriegens VnDX; E, E. coli BL21(DE3); Ctrl, Glucose dehydrogenase from Bacillus subtillis contained in each batch of fermentation as a positive control; Blue box, GOI possessing higher expression in VnDX than BL21(DE3); Orange box, GOI possessing the same expression in VnDX and BL21(DE3); Gray box, GOI possessing higher expression in BL21(DE3) than VnDX. Numbers above the lanes represent V. natriegens or E. coli strains and the detailed information of these strains were shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Classifications of the evaluation results of these 196 GOI in VnDX and BL21(DE3) according to enzyme families, sources and lengths of amino acids. (A) Classification according to enzyme family. (B) Classification according to enzyme sources. (C) Classification according to the length of enzymes. VnDX>BL21(DE3): GOI possessing higher expression in VnDX than BL21(DE3); VnDX=BL21(DE3): GOI possessing the same expression in VnDX and BL21(DE3); VnDX<BL21(DE3): GOI possessing higher expression in BL21(DE3) than VnDX.

Growth curve and protein expressions of four GOI in BHIv2, TBv2, and LBv2 culture medium. (A) Simvast acyltransferase from Aspergillus terreus. (B) D-amino acid transaminase from Silicibacter promeroyi DSS-3. (C) Haine racemase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens str. C58. (D) Maltooligosaccharide trehalose hydrolase from Arthrobacterium S 34. 0.15 OD600 (10-well gel) prepared crude protein samples were loaded to the corresponding protein gel wells. Error bars represent the SD of n = 3 technical replicates.

The growth and GDH catalytic efficiency curve of VnDX/pGDH at 30 or 28°C. (A) the growth curve of VnDX/pGDH at 30 or 28°C. (B) the GDH catalytic efficiency (U/ml) curve of VnDX/pGDH at 30 or 28°C. Error bars represent the SD of n = 3 technical replicates.

The GDH catalytic efficiency per OD600 (U⋅ml–1⋅OD–1) in BL21(DE3)/pGDH and VnDX/pGDH at the end of fermentation (24 h). Error bars represent the SD of n = 3 technical replicates.

The growth curve of V. natriegens at 37 or 30°C. Error bars represent the SD of n = 3 technical replicates.

The SDS-PAGE of soluble and insoluble expression of 3 GOI. 0.15 OD600 prepared crude protein samples were loaded to the corresponding protein gel wells. V, V. natriegens VnDX; E, E. coli BL21(DE3); Sol, soluble expression proteins; Insol, insoluble expression proteins. The GOI band is marked with red arrows. The detailed information of these GOI were shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Enzyme classification of 196 GOI in our library.

Strains and plasmids used in this work.

Detailed information of 196 GOI in E. coli and V. natriegens.

Primers used in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.