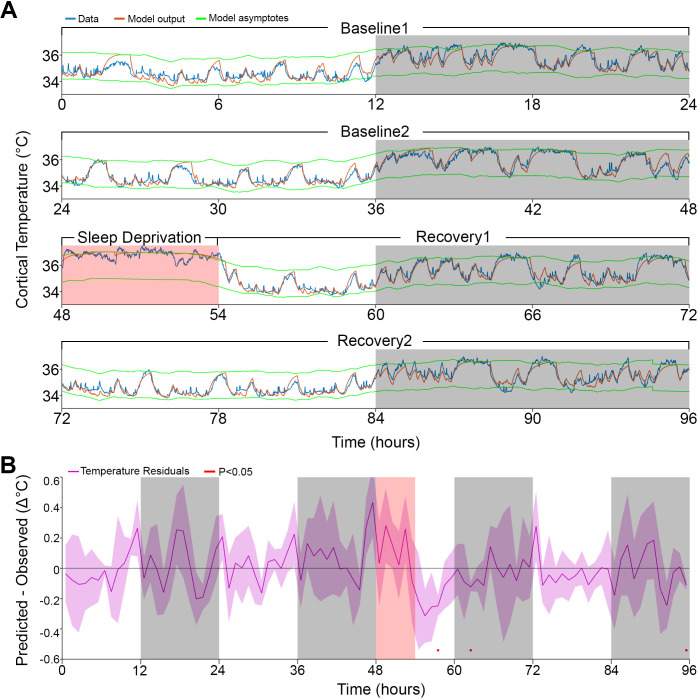

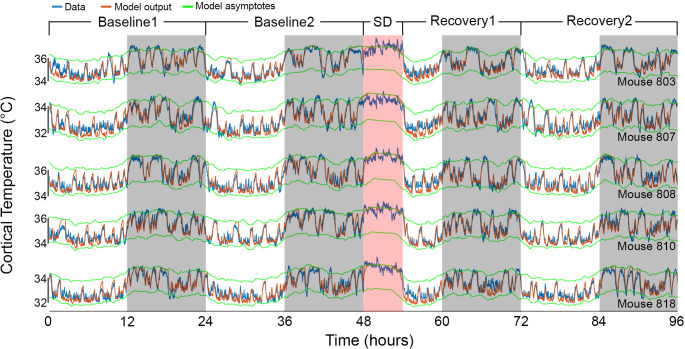

Figure 4. Model fit to a novel dataset.

(A) Representative example of the Model 2 fit (orange) to novel raw data (blue) not used for optimization, using the median of the optimized parameters from the original dataset (Table 1). (B) Temperature residuals of Model 2 (mean ± STD) across all animals in the novel dataset. Notice the small number of red markers, indicating significant deviations from zero. White/gray/salmon backgrounds in both panels indicate light/dark/sleep deprivation periods, respectively.

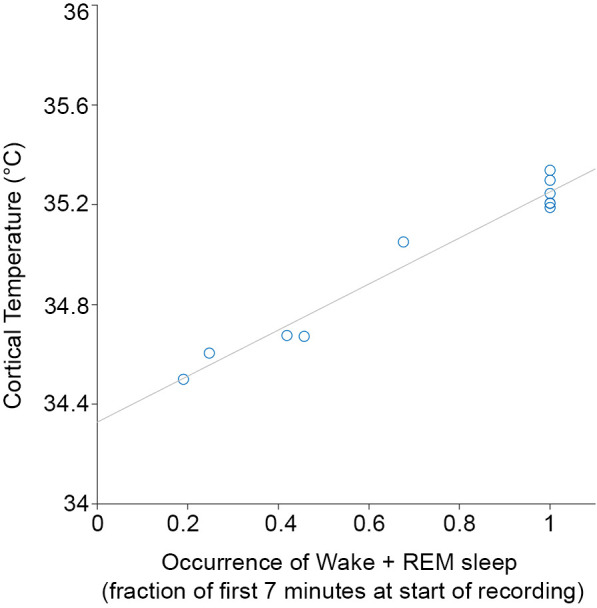

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Correlation between initial temperature to wake and rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep prevalence.