Abstract

Non-opioid therapeutics for the treatment of neuropathic pain are urgently needed to address the ongoing opioid crisis. Peptides from cone snail venoms have served as invaluable molecules to target key pain-related receptors but can suffer from unfavorable physicochemical properties, which limit their therapeutic potential. In this work, we developed conformationally constrained α-RgIA analogues with high potency, receptor selectivity and enhanced human serum stability to target the human α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. The key lactam linkage introduced in α-RgIA fixed the favored globular conformation and suppressed disulfide scrambling. The NMR structure of the macrocyclic peptide overlays well with that of α-RgIA4, demonstrating that the cyclization does not perturb the overall conformation of backbone and key side-chain residues. Finally, a molecular docking model was used to rationalize the selective binding between a macrocyclic analogue and the α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. These conformationally constrained antagonists are therefore promising candidates for antinociceptive therapeutic intervention.

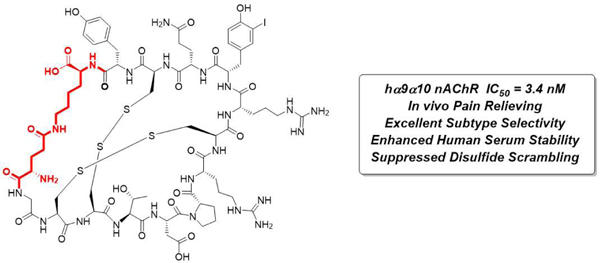

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Neuropathic pain is debilitating both physically and psychologically and is a highly prevalent complication of a large variety of diseases, including cancer, diabetes, stroke, AIDS and nerve damage.1 The use of opioid-based medications for the treatment of neuropathic pain is challenging not only because of severe side-effects but also due to the strong propensity for drug tolerance and addiction in long-term use, which has contributed to the notorious worldwide opioid overdose epidemic.2 Conotoxins (CTxs), derived from the venom of marine predatory cone snails, are promising candidates for non-opioid analgesics due to their high potency and selectivity for ion channels implicated in neuropathic pain.3 ω-conotoxin MVIIA, also known as Ziconotide (Prialt®), selectively targets voltage-gated calcium channel subtype (Cav2.2), was approved by U.S. FDA in 2004, and is used clinically for the treatment of intractable chronic pain.4

Recent studies have identified inhibition of the α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subtype as an important non-opioid based mechanism for chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain.5 Among the α9α10 nAChR antagonists, the second generation analogue α-RgIA4, modified from the parent sequence α-RgIA, crosses over the “species-related affinity gap” and exhibits high potency for both rodent (IC50 0.9 nM) and human α9α10 nAChR (IC50 1.5 nM) without inhibiting other subtypes and other pain-related receptors (> 1000 fold).6 Therefore, α-RgIA4 has great potential as a lead compound for non-opioid analgesic development. However, as with most disulfide-rich peptide drug molecules, α-RgIA4 is a poor candidate because of its low protease resistance and short plasma half-life.7 This is mainly caused by disulfide scrambling induced by thiol/disulfide exchange reactions, which result in conformational changes and substantial loss of potency due to marginal differences in the thermodynamic stabilities between the active (Globular) and inactive (Ribbon) conformations (Figure 1A).8

Figure 1.

Concept of this research. A) Rapid conformation equilibrium between globular (active) and ribbon (inactive) conformations. B) Constrained conformation disfavors conformation changes and suppresses disulfide scrambling.

Disulfide mimetics have arisen to address this issue and produce bioavailable compounds for further clinical developments, and have been applied successfully in some CTxs.9 However, disulfide mimetics may cause structural perturbation and therefore pose a risk of potency loss. For example, α-RgIA analogues having non-reducible dicarba bridges in place of native disulfides are not subject to disulfide scrambling but have significantly (two orders of magnitude) reduced potency compared with the native peptide.10 “Head-to-tail” backbone cyclization has proven to be another practical method for CTxs stabilization through hiding the flexible terminal protease recognition regions. For example, cRgIA-6, together with other backbone cyclized analogues including cVc 1.1 reported by Craik and co-workers, exhibited moderate increase in serum stability; however this increased stability came at the cost of reduced potency for human α9α10 nAChR.11 Side chain cyclization, on the other hand, is another peptide stabilization method that has been applied to some peptide drug leads recently.12 Inspired by previous studies, we aimed to introduce a third cyclization bridge at the termini through side chain cyclization to rigidify the active conformation of α-RgIA analogues while retaining binding activity (Figure 1B).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design and synthesis of conformationally constrained α-RgIA analogues.

Based on our goal to engineer a fully-active, cyclic α-RgIA4 analogue, we examined the NMR structure (PDB 2JUQ) and a recent receptor co-crystalized structure (PDB 6HY7) of α-RgIA.13 Holding a distance of around 11.6 Å, both N- and C-termini of α-RgIA reach out away from the pharmacophore. In order to accommodate the existing backbone geometry, additional amino acids at both ends would be required in order to span this distance so that the ideal linker minimally perturbs the backbone to maintain potency. Therefore, a series of side chain cyclized peptides were synthesized following a designed synthetic route depicted in Scheme 1. The newly introduced lactam bridge was synthesized on resin followed by a two-step liquid phase oxidation process in which a regioselective disulfide-bond arrangement was applied to afford the globular isomer. In detail, side-chain protected complex I was synthesized through automated Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) on 2-chlorotrityl chloride (2-CTC) resin with N-terminal Fmoc removal and re-protected with Boc. The terminal side chain amine and acid were then orthogonally deprotected (PG1 and PG2) and further cyclized to form the lactam bridged molecule complex II. The lactam cyclized peptide was generated through cleavage, purification and then underwent air oxidation to afford bicyclic product III. Finally, fully folded peptide IV was generated through an in situ iodine oxidative deprotection-disulfide formation cascade.

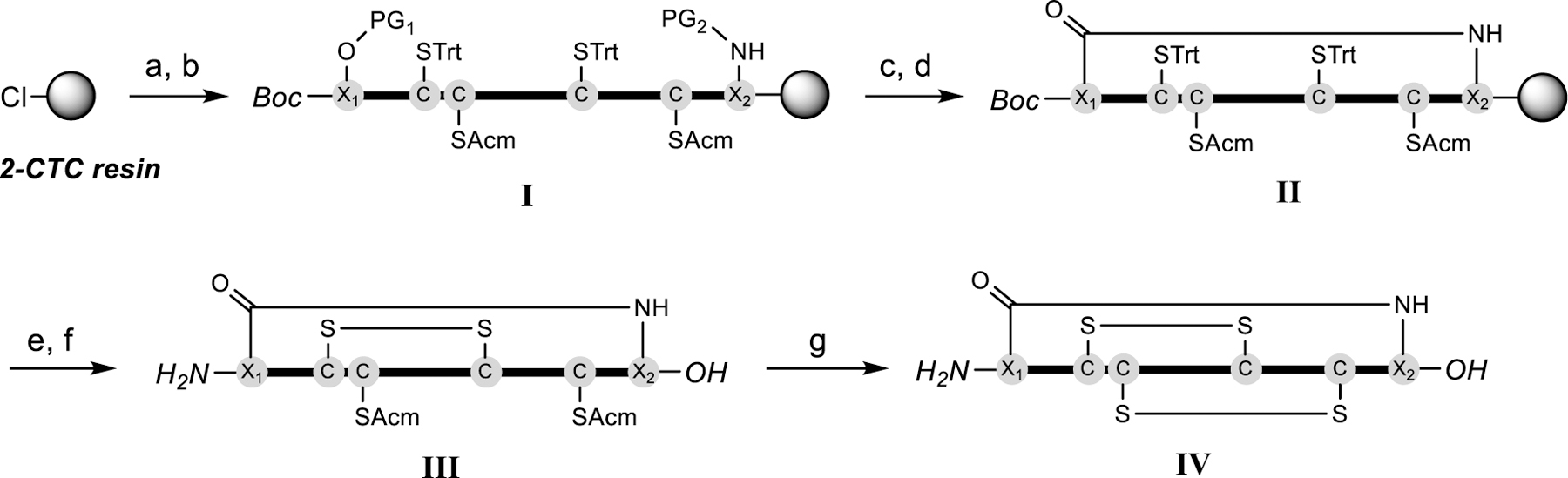

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route for macrocyclic α-RgIA analogues. a) Fmoc-SPPS. b) Boc2O, DIEA, DCM. c) Method 1 for normal tyrosine containing sequences (PG1 = allyl, PG2 = aloc): Pd(PPh3)4, DMBA, DCM; Method 2 for 3-iodotyrosine containing sequences (PG1 = Dmab, PG2 = ivDde): 5% Hydrazine in DMF. d) PyBOP, DIEA, HOBt, DMF. e) TFA:H2O:TIPS:EDT = 95:2:2:1 (v/v) then RP-HPLC. f) 0.02 M Na2HPO4 (pH 8.0), air. g) I2, AcOH, H2O. PG = protecting group.

In vitro and in vivo biological evaluation of synthesized peptides.

Prior failures in clinical trials of some α-CTx-based drug candidates demonstrated that surmounting the different sensitivities of human versus rodent nAChRs is a significant hurdle and confounding factor in the development of CTx-based analgesics.14 To address this, all our synthesized analogues were tested by two-electrode voltage-clamp electrophysiology of human α9α10 nAChR expressing X. laevis oocytes. The IC50 values generated from each concentration-response curve (Figure 2A) are listed in Table 1. Analogues 1 to 4 were synthesized to identify the optimal linker configuration. The most potent analogue 3, cyclized with terminal [Glu-Lys] side chains, is 10-fold less potent compared with α-RgIA4. The bioactivity drops significantly in analogue 1 [Asp-Dap] and 2 [Asp-Lys] when shorter linkers are generated, which are likely caused by strains and perturbations in the backbone. Analogue 4 with one CH2 unit lengthened linker by replacing Gly1 with βAla1 at the N-terminal residue of the molecule also resulted in potency drop, although not as drastic as the analogues with shorter linkers. With the best linker identified as [Glu-Lys], we then synthesized analogue 5 with 3-iodo-Tyrosine mutation which has been demonstrated as a key residue in potency increase on human α9α10 nAChR.6c The potency of analogue 5 reached 5.9 nM and was further improved to 3.4 nM (analogue 6) when Cit9 was mutated back to Arg9 (in accordance with α-RgIA5).6c Testing analogue 6 on other human nAChR subtypes to measure its selectivity showed > 10 μM potency for all subtypes except for α7 (IC50 = 504 nM, 150-fold reduction) which is also a pain-associated nAChR subtype (Figure S1). This result indicates that the current cyclization strategy produces analogue 6 with both retained potency and good receptor selectivity (Table S2). We then assessed the in vivo pain-relieving effect of analogue 6 in the oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathic pain rodent model. As shown in Figure 2B, oxaliplatin administration in mice produced cold allodynia which led to progressively reduced latency on cold plate testing while a daily co-administration of analogue 6 significantly prevented the cold allodynia. Analogue 6 is ~2-fold less potent than RgIA4 in vitro; we therefore dosed analogue 6 at 80 µg/kg compared to the 40 µg/kg used in comparable in vivo mouse studies of RgIA4. No significant difference in the in vivo pain-relieving efficacy of analogue 6 compared to RgIA4 was identified.6c Taken together, analogue 6 exhibits similar bioactivity with RgIA4 both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 2.

A) Concentration responses of synthesized analogues on human α9α10 nAChRs. Data represents separate oocytes (n = 3–6) measurement and error bar represents SD. B) Analogue 6 prevents chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain on cold-plate testing. Dose = 80 µg/kg (s.c.). Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n= 8) for each experimental determination. **p < 0.01 for Ox/6 versus Oxi/Sal, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Sal = saline; Ox = oxaliplatin; SD = standard deviation.

Table 1.

Inhibition of human α9α10 nAChR IC50 values for α-RgIA4 and synthesized analogues (1-6)a

| Peptide | Sequencesb | IC50 (nM)c | 95% CI (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RgIA4 | GCCTDPRC(Cit)(iY)QCY^ | 1.5 | 0.5–2.5 |

| 1 | [DGCCTDPRC(Cit)YQCY(Dap)]^ | 172 | 98.4–301 |

| 2 | [DGCCTDPRC(Cit)YQCYK]^ | 540 | 348–837 |

| 3 | [EGCCTDPRC(Cit)YQCYK]^ | 15.2 | 11.4–20.4 |

| 4 | [E(bA)CCTDPRC(Cit)YQCYK]^ | 33.7 | 20.9–54.3 |

| 5 | [EGCCTDPRC(Cit)(iY)QCYK]^ | 5.9 | 3.4–10.0 |

| 6 | [EGCCTDPRCR(iY)QCYK]^ | 3.4 | 2.6–4.4 |

Calculated from concentration-response curve; IC50 = half maximal inhibitory concentration.

disulfide connectivity (1–3, 2–4);

= C-terminal carboxylic acid; [ ] = side chain cyclization; Side chain cyclized amino acids are labeled in red. Cit = L-citrulline; iY = L-3-iodo-tyrosine; Dap = L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid;

A = β-alanine.

All peptides are confirmed ≥ 95% purity; RP-HPLC chromatograms for each of the peptides showing the purity are presented in the supporting information.

Human serum stability of RgIA4 and analogue 6.

Thiol-induced disulfide scrambling and proteolytic degradation in human plasma are two major threats to disulfide-rich peptide drugs. To determine how the newly introduced conformational constraint influences metabolic stability, we carried out in vitro human serum stability assay on the most potent analogue 6 in comparison with α-RgIA4. As shown in Figure 3A, analogue 6 exhibited a dramatically increased stability over α-RgIA4. Furthermore, a striking disulfide scrambling suppression was observed by HPLC analysis (Figure 3B). The front peaks are scrambled products [1,4] which were identified with isomer co-injection (Figure S2). Over half of α-RgIA4 scrambled into its ribbon isomer α-RgIA4[1,4] whereas less than 10% of analogue 6 was scrambled (Figure 3A). Taken together, these data indicated the side chain cyclization in analogue 6 greatly inhibited both proteolytic degradation and disulfide scrambling.

Figure 3.

Stability of α-RgIA4 and analogue 6 in human serum. A) Human serum stability comparison. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 separate replicates. **p < 0.01 for analogue 6 against RgIA4, student t (unpaired) test. B) Representative RP-HPLC trace of disulfide scrambling at different time points in human serum at 37 °C (Sample concentration = 0.1 mg/mL in 90% human serum).

NMR Analysis and Structure Determination.

To better understand the effect of side chain cyclization on the whole structure, we carried out NMR studies of α-RgIA4 together with analogues 3 and 6. A closely correlated secondary Hα chemical shift, particularly on the helical region from Pro6 to Gln11, indicated a high degree of structural similarity between these three molecules (Figure 4A). Slight variations were observed at the C-terminal region between α-RgIA4 and 3, whereas α-RgIA4 and 6 were more similar. Full three-dimensional solution NMR structures of α-RgIA4, 3 and 6 were then calculated using CYANA3.0. The 20 lowest energy structures from 200 calculated structures were generated with low backbone RMSD (Supporting information). Despite the differences at cyclization-constrained termini and perturbations on side chain linker, both analogue 3 and analogue 6 shared high structural similarities with α-RgIA4 (Figure 4B and 4C), particularly in the Asp5-Pro6-Arg7 “recognition finger” region which was important for receptor binding according to previous studies. Overall, the additional [Glu-Lys] side chain cyclization does not result in structural perturbation to the core of the peptide.

Figure 4.

NMR study of α-RgIA4, analogue 3 and 6. A) Secondary Hα chemical shift overlay. Residue No. 0 represents for Glu and No. 14 for Lys. B) Superposition of the representative NMR solution structure of B) α-RgIA4 (black) and 3 (red) C) α-RgIA4 (black) and 6 (blue).

Finally, a docking model of analogue 6 to the receptor based on Rosseta protein-protein docking calculations was generated to help inform SAR efforts. We found that key binding interactions revealed by the α-RgIA/α9(+) crystal structure (PDB 6HY7) were predicted by Rosetta to also be present in the case of analogue 6 binding with α9/α10 nAChR.15 Specifically, analogue 6 residues Asp5 and Arg7 form an intramolecular salt bridge, with the remaining amine on Arg7 hydrogen-bonding to the backbone carbonyl of receptor residue Pro200 on both the α9(+) and α10(+) surfaces, an interaction that is nearly identical to the reported crystal structure (Figure 5A, 5C). Additionally, Pro6 in analogue 6 forms a CH2-π interaction with Trp151 on loop-B. Further interactions show some variation between the two receptor surfaces studied here, however these apparent differences, which place some potential interacting partners barely beyond the hydrogen-bond cutoff distance, may be overstated by this model as it does not take in to account any potential induced-fit conformational changes in the receptor backbone positions upon ligand binding. Our results indicated additional interactions between Arg9 and the backbone oxygen of Thr152 in the case of the α9(+)/α9(−) interface. Receptor residue Arg59 forms hydrogen bonds with the backbone oxygen of analogue 6 residue Cys3 for both α10(+)/α9(−) and α9(+)/α9(−) and Cys8 for α10(+)/α9(−) only. Finally, residue Thr4 is predicted to form a hydrogen bond with Asp171 (Figure 5B, 5D). We note that this model does not predict direct interactions of iodo-Tyr10 to the receptor in the context of this macrocyclic analogue. The modest 2.6-fold improvement in the IC50 that was observed following iodination (Analogue 3 versus Analogue 5, Table 1) is more in line with sub-angstrom displacements to the overall conformation of the macrocycle or slight alterations to thermodynamic stability rather than the formation of an additional, direct interaction with the receptor.16 The agreement of these Rosetta models with the only reported co-complex of α-RgIA and the human α9(+) surface suggests accurate emulation of the interface during our modeling. However, given the lack of X-ray crystallography or electron microscopy data of the (−) surface with α-RgIA and α9α10 nAChR, structure determination of α-RgIA and related analogues in complex with the full receptor ECD remains an important target for future research.

Figure 5.

Selected binding model from docking of NMR structure ensemble of analogue 6 into a homology model of human (A, B) α9(+)/α9(−) and (C, D) α10(+)/α9(−) nAChR interface using RossetaDock. α9-ECD shown in green, α10-ECD in light blue and analogue 6 in orange. Key binding residues are shown as stick representation with oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur atoms in red, blue, and yellow, respectively. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds formed between analogue 6 and receptors. The hα9-ECD structure was generated from RgIA bound X-ray crystal structure (PDB 6HY7) and the hα10-ECD was generated from the previously reported homology model based on the same structure.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we have developed a side-chain cyclized α-RgIA4 analogue 6 which functions as a stabilized human α9α10 nAChR antagonist for the treatment of neuropathic pain. In vivo testing indicated that analogue 6 can prevent pain in a chemotherapy induced neuropathic pain model. Structurally, the newly introduced lactam bond provides an additional conformational constraint to rigidify the bioactive conformation and suppress disulfide scrambling, providing considerable human serum stability improvements. The current established method also has potential in stabilizing other CTxs as well as other disulfide-rich based peptide compounds for the development of novel probes and therapeutics. Based on the current research, attempts to generate a co-crystal structure of analogue 6 binding to the pentameric human α9α10 nAChRs as well as other further research are underway.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials.

All commercially available chemicals were purchased and used directly without further purification. Standard Fmoc protected amino acids were obtained from Protein Technologies Inc. Special protected amino acids including Fmoc-L-Cys(SAcm)-OH, Fmoc-L-Cit-OH, Fmoc-L-3-Iodo-Tyr-OH, Fmoc-beta-Ala-OH, Fmoc-L-Glu(OAll)-OH, Fmoc-L-Lys(NAloc)-OH, Fmoc-L-Asp(OAllyl)=OH, Fmoc-L-Glu(ODmab)-OH, Fmoc-L-Dap(NAloc)-OH, Fmoc-L-Lys(ivDde)-OH and chemicals including HATU, HOBt, PyBOP were purchased from Chemimpex Inc. 2-CTC resin was purchased from ChemPep. EDT, DIEA, DCM, TIPS, DMBA, Pd(PPh3)4, iodine, piperidine, ACh, potassium chloride, human serum and BSA were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. DMF, TFA, acetic acid, ACN and ethyl ether were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Oxaliplatin was purchased from MedChem Express.

Animals.

All experimental procedures on animals were performed in accordance with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were performed under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) approved protocols by University of Utah. Xenopus leavis frog oocytes used for two electrode voltage clamp experiments were obtained from Xenopus One. Mice (2–3 months old, male) for the oxaliplatin experiments were CBA/CaJ inbred strain, available from Jackson Laboratory. All efforts were made to reduce the number of animals used and minimize suffering during procedures.

Peptide Synthesis.

Peptides were synthesized using automated Fmoc SPPS chemistry on synthesizer (Syro I). The first amino acid was coupled manually onto 2-CTC resin (substitution = 0.77 mmol/g) and the resin was capped with MeOH to a final substitution of 0.4 mmol/g. Briefly, 250 mg of 2-CTC resin (substitution = 0.77 mmol/g) was swelled and washed in DCM for 30 min. The resin was drained and followed by adding in a solution of specific Fmoc protected amino acid (Fmoc-AA-OH = 0.1 mmol, DIEA = 0.2 mmol in DCM = 4 mL) and incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h. Then the resin was washed with DMF and DCM multiple times and incubated with 5 mL of DCM containing 16% v/v MeOH and 8% v/v DIEA for 5 min. This action was repeated for 5 times before thoroughly washed with DCM and DMF. Then the resin was set to the synthesizer for automated synthesis. Coupling reactions were performed using HATU (5.0 eq.), DIEA (10.0 eq.) and Fmoc-AA-OH (5.0 eq.) in DMF (5 mL per 0.1 mmol amino acid bonded resin) with 15 min heating to 70 °C (50 °C for Cys and Allyl and Aloc protected amino acids). Deprotection reaction was performed using 20% (v/v) Piperidine in DMF (4 mL), 5 min for 2 rounds at room temperature.

Cleavage.

Peptides were cleaved off from the resin by treatment with a cocktail buffer consisted of TFA/H2O/TIPS/EDT = 95:2:2:1 for 2.5 h at room temperature (3.0 mL per 0.1 mmol sequence bonded resin). The obtained peptide-TFA solution was then filtered and precipitated out into cold ethyl ether, centrifuged and washed with ethyl ether for at least 2 times before it was dried in vacuum. The crude product was then purified by RP-HPLC.

LC/MS analysis.

Characterization of peptides was performed by LC/MS on an Xbridge C18 5 µm (50 × 2.1 mm) column at 0.4 mL/min with a H2O/ACN gradient in 0.1% FA on an Agilent 6120 Quadrupole LC/MS system. Fractions collected from HPLC runs were also analyzed by LC/MS using the same method.

HPLC purification methods and purity check.

All samples were analyzed by the following conditions unless otherwise specified: Semi-preparative reverse phase HPLC of crude peptides was performed on Jupiter 5 µ C18 300 Å (250 × 10 mm) column at a flow rate of 3.0 mL/min with a H2O/ACN gradient containing 0.1% TFA from 5% to 35% of ACN over 45 minutes on an Agilent 1260 HPLC system. The purified fractions containing the targeted product were collected and lyophilized using a Labconco Freeze Dryer. All purity check, isomer co-injection and stability assay check were performed by HPLC on Phenomenex Gemini C18 3 µm (110 Å 150 × 3 mm) column.

On resin orthogonal deprotection and lactamization.

Method 1:

The allyl ester (OAll) and allyl carbamate (NHAloc) were removed on resin using Pd(PPh3)4 (0.1 eq.) and DMBA (4.0 eq.) in DCM (4 mL) for 2 h and this reaction was repeated for another two rounds.

Method 2:

The Pd mediated deprotection is not compatible with 3iodo-Tyr containing sequence as we have noticed that the de-Iodo product as major which may be because of Pd insertion and reduction with hydride. Thus, O(Dmab) and NH(ivDde) were used as orthogonal protection pair. The loaded resin was incubated in 5% hydrazine in DMF for 4 h and the action was repeated once. Lactam cyclization was performed on resin under the cyclization condition of PyBOP/HOBt/DIEA (2:2:2.4 eq.) in DMF and > 6 h agitation on rotator required for completion. The reaction conversion was monitored by micro-cleavage and checked by LC/MS.

Air-oxidative disulfide bond formation.

Peptide with two free Cysteines was oxidized by aerating in a 0.01 M Na2HPO4 buffer (pH = 8.0) containing 5% DMSO at room temperature for > 48 h. The reaction progress was monitored by LC/MS. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was purified by RP-HPLC using the method mentioned above.

I2-mediated disulfide bond formation.

To the stirred Bis-Acm-protected peptide solution in AcOH: H2O (80%:20% v/v, 1.00 mM) was added I2 (10.0 eq.) dissolved in AcOH in a dropwise manner at room temperature. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 10 min and monitored by LC/MS. The excess I2 was quenched by the addition of ascorbic acid solution (1.0 M, aq.) until the mixture became colorless. Then the mixture was diluted with H2O (equal volume to the reaction mixture) and purified by RP-HPLC.

Compound characterization.

All analogues synthesized and studied in this research were determined with purity ≥ 95% by HPLC. Molecular weights were measured by ESI-MS. [M+H]+ M/Z (Da): RgIA4, Calc 1691.6, Found 1691.4; Analogue 1: Calc 1749.1, Found 1749.6; Analogue 2, Calc 1791.0, Found 1791.5; Analogue 3, Calc 1804.1, Found 1804.6; Analogue 4, Calc 1819.1, Found 1819.6; Analogue 5, Calc 1931.0, Found 1931.5; Analogue 6, Calc 1929.0, Found 1929.8; RgIA4[1,4], Calc 1691.6, Found 1691.4; Analogue 6[1,4], Calc 1929.0, Found 1929.6.

Oocyte receptor expression.

X. laevis oocytes were micro-injected with cRNA encoding the selected nAChR subunits. For all the human heterologous nAChRs oocytes were injected with 15–25 ng equal parts of each subunit, and for homologous human α7 oocytes were injected with 50 ng of α7 encoding cRNA. Oocytes were incubated at 17 °C for 1–3 days in ND96 prior to use.

Electrophysiological Recordings.

Injected oocytes were placed in a 30 µL recording chamber and voltage clamped to a membrane potential of −70 mV. ND96 (96.0 mM NaCl, 2.0 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) with 0.1 mg/mL BSA was gravity perfused through the recording chamber at ~2 mL/min. A one second pulse of ACh was applied to measure receptor response, with pulses occurring every minute. ACh was applied at a concentration of 100 µM for all subtypes, with the exception of 200 µM for α7 and 10 µM for the muscle subtype. A baseline ACh response was established, and then the ND96 control solution was switched to a ND96 solution containing the various concentrations of test peptides. During perfusion of the peptide-containing solutions, ACh pulses continued once per minute to assess for block of the ACh-induced response. ACh responses were measured in the presence of a peptide concentration until the responses reached steady state; an average of three of these responses compared to the baseline response was used to determine percent response. Due to limited material, for 10 µM concentration testing, 3 µl of 100 µM peptide was introduced into the 30 µl recording chamber with the ND96 flow stopped. After 5 minutes of incubation, the ND96 flow and ACh pulses resumed to measure any block by peptide. All concentration-response analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism software; values, including the resulting IC50 were calculated using a non-linear regression (curve fit) sigmoidal dose-response (variable-slope).

Oxaliplatin-Induced Cold Allodynia.

Oxaliplatin was dissolved at 0.875 µg/µl in 0.9% sterile saline. Analogue 6 was dissolved at 0.02 µg/µl in 0.9% sterile saline. CBA/CaJ mice (male, 2–3 months old) were injected daily (excluding weekends) i.p. with oxaliplatin (3.5mg/kg) or 0.9% saline (vehicle). Mice (n = 8 for each treatment group) were also injected daily s.c. with analogue 6 (80 µg/kg) or 0.9% saline as control. All compounds were blinded for the experimenter in this study. The study began with an initial baseline cold sensitivity testing on a Wednesday, and injections were administered during the first week on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. Injections continued Monday-Friday for two more weeks, with testing on Wednesdays 24 hours after the previous day’s injection. The final week, injections occurred on Monday and Tuesday, and the final testing day occurred 24 hours later.

Cold Plate Test.

Testing was performed using a hot/cold plate machine purchased from IITC Life Science. Test mice (n = 8 for each treatment group) were allowed to acclimate to the testing chamber with the plate held at room temp (23 °C) until investigative behavior subsided. Temperature was then lowered on a linear ramp at a rate of 10 °C per minute. The test was stopped when the mouse lifted both forepaws and vigorously shook them or repeatedly licked the footpad. Lifting of one forepaw at a time or alternating back and forth between paws was not scored and the testing continued. Final time and temperature was recorded and the resulting data was plotted using Graphpad Prism. Data was analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test. P-values were, * P < 0.05, ** P <0.01, and *** P <0.001 for significant difference from oxaliplatin/saline control.

In Vitro Human Serum Stability Test.

Peptides (RgIA4 and analogue 6) were dissolved in H2O (1.0 mg/mL) and 100 µL of this solution was added into 900 µL of human serum from human male AB plasma which is first-time defrosted, sterile filtered and pre-centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min to remove lipid. Final peptide concentration was 0.1 mg/mL. Solutions were then incubated in 37 °C water bath and individual 100 µL of the solution was taken up at certain, pre-determined time points and denatured with 300 µL ACN and cooled on ice for 30 mins. The suspension was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 mins at room temperature. Then 10 µL of supernatant was taken up and dissolved in 10 µL of Buffer A (0.1% TFA in H2O) to make the HPLC sample. The samples were analyzed by HPLC (injection volume = 15 µL; column: Phenomenex, 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 100 Å, 5 μm) with a linear gradient of 5–50% B over 8 mins (A = H2O + 0.1% FA and B = ACN + 0.1% FA; 0.4 mL/min flow rate). Peptide peak areas were integrated on 220 nm and the % of peptide left, compared to the initial was graphed against the time. The serum stability experiments were repeated independently for 3 times of each peptide. Data analysis were performed with GraphPad Prism software. Data was analyzed using Student t (unpaired) test where ** P <0.01 stands for significant difference between RgIA4 versus analogue 6.

NMR Spectroscopy.

Peptide samples were prepared in a pH 3.5 buffer consist of (20 mM Na2HPO4, 50 mM NaCl, 50 µM NaN3 and 0.1 mM EDTA) containing 10% D2O at 2.0 mM (uncorrected for isotope effects). Spectra were recorded on an Inova 500 and 600 MHz spectrometer at 298 K. Spectrometers were set with VnmrJ4.0. The 2D experiments including TOCSY (80 ms), gCOSY, NOESY (200 ms), g11-NOESY and 13C-HSQC were generated. Samples were loaded in Shigemi tube for data collection and water suppression was achieved using excitation sculpting with gradients. Spectra were processed with software NMRPipe and chemical shifts were assigned with SPARKY.

Structure Calculation.

The 3D structures in this research were calculated by deriving inter-proton distance restraints from the intensity of cross-peaks in NOESY (200 ms) and g11-NOESY spectra using CYANA 3.0. Special amino acid libraries (3-iodoTyr, Linked Glu and Lys) were modified on side chain based on natural amino acids. Pseudo-atom corrections were applied to non-stereospecifically assigned protons. Constraints for the φ, ψ and χ1 backbone dihedral angles were generated from TALOS based on the Hα, Cα, Cβ, and HN chemical shifts. The structures were demonstrated using the program PyMOL and refined with Rosseta.

Docking Study.

Two general classes of analogue 6 conformers were represented in the 20 lowest energy ensembles from the NMR data. Both of these classes were analyzed in Rosetta, however only one class (containing 17 of the 20 ensemble structures) generated docked coordinates which successfully reproduced known interactions resolved in the crystal structure of RgIA with α9 subunit (PDB 6HY7). The lowest energy conformer from that class was selected for generating a hypothetical binding model for analogue 6 at α9/α10 nAChR subunit interfaces using Rosetta. Structures of α9 were taken from PDB entries 6HY7 and 4D01, and the homology-modeled coordinates for α10 were taken from previous report.13b Mutational experiments in vitro have indicated that α-RgIA likely binds the α9(+)/α9(−) and α10(+)/α9(−) interfaces preferentially over the α9(+)/α10(−) interface, so only α9(+)/α9(−) and α10(+)/α9(−) were chosen for modeling in Rosetta. Initial docking runs of analogue 6 against receptor subunit interfaces were done using Rosetta Docking Protocol, and allowed for random translational and rotational perturbation of the starting position of analogue 6 at the acetylcholine binding site by 3Å and 8°. The Rosetta docking metrics I_sc and rms for the resulting 1000 coordinate files were plotted on a 2D scatter plot (supporting information), revealing that positioning of analogue 6 in the acetylcholine binding site (aligned to RgIA in PDB file 6HY7) provided the most favorable I_sc scores. There was a significant correlation between I_sc and rms, indicating convergence during the initial docking step. Further refinement of the interface interactions was done using the [-docking_local_refine flag]. The local refinement results were clustered using I_rms and I_sc to ensure that high-scoring results were not outliers and a final minimization step was done using Rosetta Relax.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is supported by U.S. Department of Defense NIGMS GM125001, GM103801 and GM136430. We thank Prof. Jack Skalicky for the help of NMR study and docking discussion. We thank Prof. Helena Safavi-Hamami, Dr. Joanna Gajewiak, Dr. Weiliang Xu and Yi Wolf Zhang for help and discussions.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- ACh

acetylcholine

- Acm

acetamidomethyl

- ACN

acetonitrile

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CTxs

conotoxins

- 2-CTC

2-chlorotrityl chloride

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DIEA

diisopropylethylamine

- DMBA

N,N-dimethylbarbituric acid

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDT

1,2-ethanedithiol

- FA

formic acid

- HATU

O-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- nAChRs

nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

- PyPOB

benzotriazol-1-yloxy)tripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate

- RP

reversed phase

- s.c.

subcutaneous injection

- SPPS

solid phase peptide synthesis

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TIPS

triisopropylsilane

- Trt

trityl

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Supporting tables and figures, HPLC trace, ESI-MS characterization, NMR chemical shift assignments table and NMR spectra of compounds (PDF)

20 lowest energy states ensemble of NMR solution structures for RgIA4 (PDB), analogue 3 (PDB) and analogue 6 (PDB)

Docking models of analogue 6 bound with α9(+)/α9(−) (PDB) and α10(+)/α9(−) (PDB) nAChR subtype interfaces using Rosetta Dock.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Murnion BP Neuropathic Pain: Current Definition and Review of Drug Treatment. Aust. Prescr 2018, 41, 60–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Brady KT; McCauley JL; Back SE Prescription Opioid Misuse, Abuse, and Treatment in the United States: An Update. Am J Psychiatry 2016, 173, 18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Burke DS Forecasting the Opioid Epidemic. Science 2016, 354, 529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Alonso D; Khalil Z; Satkunanthan N; Livett BG Drugs from the Sea: Conotoxins as Drug Leads for Neuropathic Pain and Other Neurological Conditions. Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 2003, 3, 785–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Layer RT; McIntosh JM Conotoxins: Therapeutic Potential and Application. Mar Drugs 2006, 4, 119–142. [Google Scholar]; (c) Livett BG; Sandall DW; Keays D; Down J; Gayler KR; Satkunanathan N; Khalil Z Therapeutic Applications of Conotoxins that Target the Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Toxicon 2006, 48, 810–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Netirojjanakul C; Miranda LP Progress and Challenges in the Optimization of Toxin Peptides for Development as Pain Therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2017, 38, 70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Safavi-Hemami H; Brogan SE; Olivera BM Pain Therapeutics from Cone Snail Venoms: From Ziconotide to Novel Non-opioid Pathways. J. Proteomics 2019, 190, 12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sanford M Intrathecal Ziconotide: A Review of Its Use in Patients with Chronic Pain Refractory to Other Systemic or Intrathecal Analgesics. CNS Drugs 2013, 27, 989–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) McIntosh JM; Absalom N; Chebib M; Elgoyhen AB; Vincler M Alpha9 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors and the Treatment of Pain. Biochem. Pharmacol 2009, 78, 693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mohammadi SA; Christie MJ Conotoxin Interactions with α9α10-nAChRs: Is the α9α10-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor an Important Therapeutic Target for Pain Management? Toxins 2015, 7, 3916–3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hone AJ; Servent D; McIntosh JM α9-Containing Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors and the Modulation of Pain. Br. J. Pharmacol 2018, 175, 1915–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Ellison M; Haberlandt C; Gomez-Casati ME; Watkins M; Elgoyhen AB; McIntosh JM; Olivera BM α-RgIA: A Novel Conotoxin that Specifically and Potently Blocks the α9α10 nAChR. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 1511–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Christensen SB; Hone AJ; Roux I; Kniazeff J; Pin JP; Upert G; Servent D; Glowatzki E; McIntosh JM RgIA4 Potently Blocks Mouse α9α10 nAChRs and Provides Long Lasting Protection against Oxaliplatin-Induced Cold Allodynia. Front. Cell. Neurosci 2017, 11, 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Romero HK; Christensen SB; Di Cesare Mannelli L; Gajewiak J; Ramachandra R; Elmslie KS; Vetter DE; Ghelardini C; Iadonato SP; Mercado JL; Olivera BM; McIntosh JM Inhibition of α9α10 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Prevents Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114, E1825–E1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Akondi KB; Muttenthaler M; Dutertre S; Kaas Q; Craik DJ; Lewis RJ; Alewood PF Discovery, Synthesis, and Structure-Activity Relationships of Conotoxins. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 5815–5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jin AH; Muttenthaler M; Dutertre S; Himaya SWA; Kaas Q; Craik DJ; Lewis RJ; Alewood PF Conotoxins: Chemistry and Biology. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 11510–11549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Moroder L; Musiol HJ; Gotz M; Renner C Synthesis of Single- and Multiple- Stranded Cystine-Rich Peptides. Biopolymers 2005, 80, 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bulaj G; Olivera BM Folding of Conotoxins: Formation of the Native Disulfide Bridges during Chemical Synthesis and Biosynthesis of Conus Peptides. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 2008, 10, 141–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) MacRaild CA; Illesinghe J; van Lierop BJ; Townsend AL; Chebib M; Livett BG; Robinson AJ; Norton RS Structure and Activity of (2,8)-Dicarba-(3,12)-cystino α-ImI, an α-Conotoxin Containing a Nonreducible Cystine Analogue. J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Muttenthaler M; Nevin ST; Grishin AA; Ngo ST; Choy PT; Daly NL; Hu SH; Armishaw CJ; Wang CI; Lewis RJ; Martin JL; Noakes PG; Craik DJ; Adams DJ; Alewood PF Solving the α-Conotoxin Folding Problem: Efficient SeleniumDirected On-Resin Generation of More Potent and Stable Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Antagonists. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 3514–3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) de Araujo AD; Callaghan B; Nevin ST; Daly NL; Craik DJ; Moretta M; Hopping G; Christie MJ; Adams DJ; Alewood PF Total Synthesis of the Analgesic Conotoxin MrVIB through Selenocysteine-Assisted Folding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 6527–6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Dekan Z; Vetter I; Daly NL; Craik DJ; Lewis RJ; Alewood PF α-Conotoxin ImI Incorporating Stable Cystathionine Bridges Maintains Full Potency and Identical Three-Dimensional Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 15866–15869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) de Araujo AD; Mobli M; Castro J; Harrington AM; Vetter I; Dekan Z; Muttenthaler M; Wan J; Lewis RJ; King GF; Brierley SM; Alewood PF Selenoether Oxytocin Analogues have Analgesic Properties in a Mouse Model of Chronic Abdominal Pain. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Gori A; Wang CI; Harvey PJ; Rosengren KJ; Bhola RF; Gelmi ML; Longhi R; Christie MJ; Lewis RJ; Alewood PF; Brust A Stabilization of the Cysteine-Rich Conotoxin MrIA by Using a 1,2,3-Triazole as a Disulfide Bond Mimetic. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 1361–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Gori A; Gagni P; Rinaldi S Disulfide Bond Mimetics: Strategies and Challenges. Chem. Eur. J 2017, 23, 14987–14995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Knuhtsen A; Whitmore C; McWhinnie FS; McDougall L; Whiting R; Smith BO; Timperley CM; Green AC; Kinnear KI; Jamieson AG α-Conotoxin GI Triazole-Peptidomimetics: Potent and Stable Blockers of a Human Acetylcholine Receptor. Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 1671–1676. [Google Scholar]; (i) Qu Q; Gao S; Wu F; Zhang M-G; Li Y; Zhang L-H; Bierer D; Tian C-L; Zheng J-S; Liu L Synthesis of Disulfide Surrogate Peptides Incorporating Large-Span Surrogate Bridges Through a Native-Chemical-Ligation-Assisted Diaminodiacid Strategy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Chhabra S; Belgi A; Bartels P; van Lierop BJ; Robinson SD; Kompella SN; Hung A; Callaghan BP; Adams DJ; Robinson AJ; Norton RS Dicarba Analogues of α-Conotoxin RgIA. Structure, Stability, and Activity at Potential Pain Targets. J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 9933–9944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) Clark RJ; Fischer H; Dempster L; Daly NL; Rosengren KJ; Nevin ST; Meunier FA; Adams DJ; Craik DJ Engineering Stable Peptide Toxins by Means of Backbone Cyclization: Stabilization of the α-Conotoxin MII. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2005, 102, 13767–13772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Clark RJ; Jensen J; Nevin ST; Callaghan BP; Adams DJ; Craik DJ The Engineering of an Orally Active Conotoxin for the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010, 49, 6545–6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Halai R; Callaghan B; Daly NL; Clark RJ; Adams DJ; Craik DJ Effects of Cyclization on Stability, Structure, and Activity of α-Conotoxin RgIA at the α9α10 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor and GABAB Receptor. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 6984–6992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang CK; Craik DJ Designing Macrocyclic Disulfide-Rich Peptides for Biotechnological Applications. Nat. Chem. Biol 2018, 14, 417–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Sadeghi M; Carstens BB; Callaghan BP; Daniel JT; Tae HS; O’Donnell T; Castro J; Brierley SM; Adams DJ; Craik DJ; Clark RJ Structure-Activity Studies Reveal the Molecular Basis for GABAB-Receptor Mediated Inhibition of High Voltage-Activated Calcium Channels by α-Conotoxin Vc1.1. ACS. Chem. Biol 2018, 13, 1577–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Miranda LP; Winters KA; Gegg CV; Patel A; Aral J; Long J; Zhang J; Diamond S; Guido M; Stanislaus S; Ma M; Li H; Rose MJ; Poppe L; Veniant MM Design and Synthesis of Conformationally Constrained Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Derivatives with Increased Plasma Stability and Prolonged in Vivo Activity. J. Med. Chem 2008, 51, 2758–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Murage EN; Gao G; Bisello A; Ahn JM Development of Potent Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Agonists with High Enzyme Stability via Introduction of Multiple Lactam Bridges. J. Med. Chem 2010, 53, 6412–6420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Khoo KK; Wilson MJ; Smith BJ; Zhang M-M; Gulyas J; Yoshikami D; Rivier JE; Bulaj G; Norton RS Lactam-Stabilized Helical Analogues of the Analgesic μ-Conotoxin KIIIA. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 7558–7566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hoang HN; Song K; Hill TA; Derksen DR; Edmonds DJ; Kok WM; Limberakis C; Liras S; Loria PM; Mascitti V; Mathiowetz AM; Mitchell JM; Piotrowski DW; Price DA; Stanton RV; Suen JY; Withka JM; Griffith DA; Fairlie DP Short Hydrophobic Peptides with Cyclic Constraints Are Potent Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor (GLP-1R) Agonists. J. Med. Chem 2015, 58, 4080–4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yang D; Qin W; Shi X; Zhu B; Xie M; Zhao H; Teng B; Wu Y; Zhao R; Yin F; Ren P; Liu L; Li Z Stabilized β-Hairpin Peptide Inhibits Insulin Degrading Enzyme. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 8174–8185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Dougherty PG; Wen J; Pan X; Koley A; Ren J-G; Sahni A; Basu R; Salim H; Kubi GA; Qian Z; Pei D Enhancing the Cell Permeability of Stapled Peptides with a Cyclic Cell-Penetrating Peptide. J. Med. Chem 2019, 62, 1009810107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Ellison M; Feng ZP; Park AJ; Zhang X; Olivera BM; McIntosh JM; Norton RS α-RgIA, a Novel Conotoxin That Blocks the α9α10 nAChR: Structure and Identification of Key Receptor-Binding Residues. J. Mol. Biol 2008, 377, 1216–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zouridakis M; Papakyriakou A; Ivanov IA; Kasheverov IE; Tsetlin V; Tzartos S; Giastas P Crystal Structure of the Monomeric Extracellular Domain of α9 Nicotinic Receptor Subunit in Complex With α-Conotoxin RgIA: Molecular Dynamics Insights into RgIA Binding to α9α10 Nicotinic Receptors. Front. Pharmacol 2019, 10, 474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Pennington MW; Czerwinski A; Norton RS Peptide Therapeutics from Venom: Current Status and Potential. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2018, 26, 2738–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Azam L; McIntosh JM Molecular Basis for the Differential Sensitivity of Rat and Human α9α10 nAChRs to α-Conotoxin RgIA. J. Neurochem 2012, 122, 11371144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Azam L; Papakyriakou A; Zouridakis M; Giastas P; Tzartos SJ; McIntosh JM Molecular Interaction of α-Conotoxin RgIA with the Rat α9α10 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Mol. Pharmacol 2015, 87, 855–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu R; Tae HS; Tabassum N; Shi J; Jiang T; Adams DJ Molecular Determinants Conferring the Stoichiometric-Dependent Activity of α-Conotoxins at the Human α9α10 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subtype. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 4628–4634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li R; Li X; Jiang J; Tian Y; Liu D; Zhangsun D; Fu Y; Wu Y; Luo S Interaction of Rat a9a10 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor with a Conotoxin RgIA and Vc1.1: Insights from Docking, Molecular Dynamics and Binding Free Energy Contributions. J. Mol. Graph. Model 2019, 92, 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Shinada NK; de Brevern AG; Schmidtke P Halogens in Protein–Ligand Binding Mechanism: A Structural Perspective. J. Med. Chem 2019, 62, 21, 9341–9356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hosseini AS; Pace CJ; Esposito AA; Gao J Non-additive Stabilization by Halogenated Amino Acids Reveals Protein Plasticity on a Sub-angstrom Scale. Protein Sci 2017, 26, 2051–2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.