Foreword

The ASHP Foundation Pharmacy Forecast has been a valuable source of insight and guidance about our profession as it is influenced by or influences external factors in our environment. ASHP and the ASHP Research and Education Foundation (“the Foundation”) present this ninth edition of the annual Pharmacy Forecast and are pleased to disseminate the Pharmacy Forecast through AJHP, providing readers with easy access to the report. The staff of AJHP has provided substantial editorial support for this publication, and we appreciate their assistance.

The Pharmacy Forecast is a vital component of ASHP’s efforts to advance pharmacy practice leadership, and the Foundation appreciates the many pharmacists and others who have contributed to the David A. Zilz Leaders for the Future fund, which provides the resources to develop the report. The Foundation is also grateful to Omnicell for their support of the Zilz fund, which has made the Pharmacy Forecast possible. The Pharmacy Forecast could not be created without the contributions of the report’s founding editor, William Zellmer; members of the Forecast 2021 Advisory Committee; Forecast Panelists (FPs) who responded to the forecast survey; and chapter authors. ASHP and the Foundation are indebted to those individuals who have helped make the 2021 edition a success.

Over the past 8 years, the Pharmacy Forecast has provided insight into emerging trends and phenomena that have impacted the practice of pharmacy and the health of patients in health systems. The value of the report is determined by its value to health-system pharmacists and health-system pharmacy leaders as they use the report to inform their strategic planning efforts. The Pharmacy Forecast is not intended to be an accurate prediction of future events. Rather, the report is intended to be a provocative stimulant for the thinking, discussion, and planning that must take place in every hospital and health system in order for those organizations to succeed in their mission of caring for patients and advancing the profession of pharmacy. Some may disagree with the opinions of the FPs or the positions taken by individual chapter authors with respect to their vision of the future. That is acceptable and desirable. Also, the report reflects a consensus of the national direction and may not reflect what is likely to occur in your geographic region or state. Reflect those differing opinions in your organization’s strategic planning process and chart a course for your organization that is consistent with your beliefs, and the Pharmacy Forecast will have met its objective of encouraging planning efforts of health systems.

We welcome your comments on this new 2021 edition of the Pharmacy Forecast. Suggestions for future forecasts can be sent to any of the forecast editors through the Foundation’s Pharmacy Forecast website at http://www.ashpfoundation.org/pharmacyforecast and will be considered for future editions.

Introduction and Methods

Joseph T. DiPiro, PharmD, FCCP, FAAAS, Dean, School of Pharmacy, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA

Address correspondence to Dr. DiPiro (jtdipiro@vcu.edu).

An underlying assumption supporting the need for the Pharmacy Forecast is that many factors influencing our profession and pharmacy services are not directly under our control, yet we can take actions that enhance the likelihood of favorable outcomes within this environment. Those influencing factors may be as a specific state or national policy or regulation, or as nebulous as the trend toward globalization (or anti-globalization). Other than the COVID-19 pandemic, the influencing factors such as the prominence of “big data,” issues of personal privacy, financing and health access are not new and have emerged over time. Within that context, then, we have greatest control over the scope of our pharmacy enterprise and the workforce within that enterprise, and some control over those factors where we can advocate to the decision makers (such as health-system administrators, legislators, and government agency officials). The perspective gained from reading the 2021 Pharmacy Forecast is most effectively used within the process of strategic planning as part of environmental scanning or when identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, or threats (SWOT). In addition, the recommendations provided below can be part of the institution’s strategic planning action steps.

FORECAST METHODS

The methods used to develop the 2021 Pharmacy Forecast were similar to those used in the previous editions, drawing on concepts described in James Surowiecki’s book The Wisdom of Crowds.1 According to Surowiecki, the collective opinions of “wise crowds”—groups of diverse individuals in which each participant’s input is provided independently, drawing from their own locally informed points of view—can be more informative than the opinion of any individual participant. This process is particularly valuable when addressing phenomena that are not well suited to quantitative predictive methods. A critical requirement for successfully creating crowd-based knowledge is establishing a systematic method of combining individual beliefs into a collective opinion—the Pharmacy Forecast uses a survey of carefully selected pharmacy leaders to derive our environmental scan.

The 2021 Pharmacy Forecast Advisory Committee (see membership list in the Foreword) began the development of survey questions by contributing lists of issues and concerns they believed will influence health-system pharmacy in the coming 5 years. That list was then expanded and refined through an iterative process, resulting in a final set of 7 themes, each with 6 focused topics on which the survey was built. Each of 42 survey items was written to explore the selected topics and was pilot tested to ensure clarity and face validity.

As in the past, Pharmacy Forecast survey respondents—the Forecast Panelists (FPs)—were selected by ASHP staff after nomination by the leaders of the ASHP sections. Nominations were limited to individuals known to have expertise in health-system pharmacy and knowledge of trends and new developments in the field. The size of and representation within the Forecast Panel were intended to capture opinions from a wide range of pharmacy leaders.

The Pharmacy Forecast survey instructed FPs to read each of the 42 scenarios represented in survey items and consider the likelihood of those scenarios occurring in the next 5 years. They were asked to base their response on their firsthand knowledge of current conditions in their region, not on their understanding of national circumstances. The panel was carefully balanced across the census regions of the United States to reflect a representative national picture. They were asked to provide a top-of-mind response regarding the likelihood of those conditions being very likely, somewhat likely, somewhat unlikely, or very unlikely to occur.

This year we chose to present (in related articles in this issue of AJHP) additional insights on Pharmacy Forecast topics in the light of major societal factors, the U.S. presidential election, the COVID-19 pandemic, and racial equity and social justice within our country. William Zellmer was invited to reflect on the developing political environment after our national election and how it could impact healthcare.2 Suzanne Shea was invited to address the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on selected topics within the Pharmacy Forecast survey.3 And Bruce Scott was invited to address the intersection of racial equity and healthcare.4

FORECAST SURVEY RESULTS

The strength (and possibly validity) of predictions generated using the “wisdom of the crowd” method is largely dependent on the nature of the panelists responding to the forecast survey. Therefore, it is important to understand the composition and characteristics of the panel.

A total of 319 FPs were recruited to complete the forecast survey. Responses were received from 272 (an 85.3% response rate, similar to the response rates in previous years). Most of the FPs (83%) had been in practice for greater than 10 years, and 53% had been in practice for greater than 20 years. Most FPs (53%) described their practice setting as a teaching hospital or health system, while 14% of FPs were from nonteaching hospitals or health systems. Twenty-one percent were from academia, compared with 13% the previous year. FPs reported that their primary organizations offered diverse services, including home health or infusion care (47%), oncology (69%), specialty pharmacy (59%), ambulatory care (77%), pediatric care (55%), and hospice care (38%). Sixty-five percent of their organizations had a retail pharmacy and 23% provided nursing home/long-term care.

Many of the FPs hold the title of chief pharmacy officer, director of pharmacy, or associate/assistant director of pharmacy (14%, 17%, and 6% of FPs, respectively). Eleven percent of FPs listed their primary position as “clinical pharmacist” (generalist or specialist) and 3% as “clinical coordinator.” Another 21% described their primary role as faculty. Eight percent of respondents indicated informatics/technology specialist as their primary position (compared with 6% the previous edition). The remainder of FPs included leaders and practitioners at varying levels and with varying titles. Fifty-nine percent of FPs were employed by hospitals with 400 or more beds, and 12% of respondents were from hospitals of less than 400 beds. Overall, the composition of the Forecast Panel was similar to that in previous years. As shown in Table 1, the percent of total responses from each U.S. region ranged from 6% in New England and the Middle South to 20% in the Great Lakes region. In the 2021 survey, every region was represented by a minimum of 15 FP respondents.

Table 1.

Forecast Survey Responses by Region

| Region | Percent of 272 Total Responses |

|---|---|

| New England (ME, NH, VT, MA, RI, CT) | 6 |

| Mid-Atlantic (DE, NY, NJ, PA) | 9 |

| South Atlantic (MD, DC, VA, WV, NC, SC, GA, FL) | 18 |

| Southeast (KY, TN, AL, MS) | 11 |

| Great Lakes (OH, IN, IL, MI, WI) | 20 |

| Western Plains (MN, IA, MO, ND, SD, NE, KS) | 11 |

| Middle South (AR, LA, OK, TX) | 6 |

| Mountain (MT, ID, WY, CO, NM, AZ, UT, NV) | 7 |

| Pacific (WA, OR, CA, AK, HI) | 12 |

CONTENTS OF THE 2021 PHARMACY FORECAST

Each section of the report provides a summary of the survey findings, assessment and perspective of the chapter author, and strategic recommendations. While the individual survey items focus on a specific projection of the future, the full breadth of discussion in each chapter is broad and links related items when appropriate.

The first chapter, by Erin Fox and Aron Kesselheim, focuses on the global drug supply chain. A generally accepted assumption is that the world at large and the United States will likely experience calamities such as the COVID-19 pandemic and breaches in cybersecurity that could disrupt the availability or reduce the quality of medications. What can and should we do within health systems to prepare for these possibilities?

While access to healthcare has always been an issue, it has received greater visibility and urgency as our nation struggles with racial equity. Marie Chisholm-Burns, Christopher Finch, and Christina Spivey addressed healthcare access topics. The emergence of new communication technology provides greater opportunity to expand access to underserved populations. Advancement in pharmacists’ scope of practice and technician roles provide further opportunity for extension of pharmacy services to populations in need.

As pharmacy services and healthcare in general have become more data-complex, effective and ethical use of data has become ever more important. Jannet Carmichael and Joy Meier discuss the implications of data use to develop more efficient and consistent models of care, and also the ethical issue of privacy in systems that have access to a greater extent of patient and employee data.

Healthcare financing, a persistent topic for past Forecast editions, is addressed by Thomas Woller and Brian Pinto and includes a wide scope of topics from pharmacy benefit manager transparency to contracts with online distributors and value-based contracts. The tax-exempt status of health systems is another topic of discussion in the chapter as requirements for the charity-care requirement are under scrutiny by federal and state governments.

Patient safety is addressed in the chapter by James Hoffman and David Bates and continues the discussion from previous editions of Pharmacy Forecast. The authors discuss the “zero harm” paradigm as an opportunity to change the way we think about medication safety. They also address the role of the pharmacists as patient safety leaders and the roles of pharmacy and therapeutics committees. They tie in staff resilience and well-being to patient safety.

We are all aware that the scope of the pharmacy enterprise in health systems has grown and changed substantially in the past decade. John Armitstead and Dorinda Segovia discuss expansion of access to pharmacists in primary care settings as well as the potential for pharmacist redeployment from traditional acute care positions. They also discuss institutional credentialing processes and likely changes in the extent and documentation of pharmacy services.

Along with changes in the pharmacy enterprise, there have been and will continue to be changes in our pharmacy workforce, and these issues are addressed by Melanie Dodd and Mollie Ashe Scott. Among the issues that have been before us for years are pharmacist provider status and prescribing authority. They also discuss the opportunity to enhance pharmacist roles through automatic verification of medication orders and expanded roles of technicians. Finally, the pharmacist workforce, including resident recruitment, could significantly be impacted by a reduction in the number of pharmacy graduates across the country.

USER’S GUIDE TO THE PHARMACY FORECAST

The focus of the Pharmacy Forecast is on large-scale, long-term trends that will influence us over months and years and not on day-to-day situational dynamics. The 2021 edition of the Pharmacy Forecast differs from past editions by inclusion of new, timely topics while continuing the discussion of topics that have remained important from previous years.

The report is intended to stimulate thinking and discussion, providing a starting point for individuals and teams who wish to proactively position themselves and their teams and departments for potential future events and trends rather than be reactive to those things that occur.

This is the most appropriate level of focus for strategic planning. As the process of strategic planning should involve pharmacy staff at all levels, the Pharmacy Forecast provides guidance to anyone participating in health-system strategic planning activities, and it is recommended that the report be reviewed by all involved.

When using the Pharmacy Forecast, it is recommended that planners review at least 1 or 2 past editions in addition to this new report; many of the observations and recommendations that are 1 or 2 years old remain important to consider. Past editions of the Pharmacy Forecast can be found on the ASHP Foundation website at http://www.ashpfoundation.org/pharmacyforecast.

Those organizations involved in education or training should consider the use of the Pharmacy Forecast as a teaching tool. Many educators and residency preceptors use the report as part of coursework, seminars, or journal club sessions to help engage pharmacy trainees in thinking about the future of the profession they are preparing to enter.

Finally, as the pharmacy workforce is increasingly relied upon to provide system-wide leadership, the Pharmacy Forecast addresses many issues that are relevant well beyond the traditional boundaries of pharmacy and the medication-use process. The content of the report should inform the broadened scope of responsibility that many pharmacists now take. The Pharmacy Forecast should be shared with other senior health-system leaders and executives as a resource to help them understand the challenges facing pharmacy and to help them recognize the way emerging healthcare trends will affect many other areas of health systems.

Disclosures

Dr. DiPiro currently serves on the AJHP Editorial Advisory Board.

Reference

- 1. Surowiecki J. The wisdom of crowds. Anchor; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zellmer WA. How pharmacists can help heal democracy in America. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2021;78(6):xxx-xxx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 3. Shea SB. Reflections on the COVID-19 pandemic and Pharmacy Forecast 2019. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2021;78( 6):xxx-xxx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scott B. Racial and ethnic equality is also about healthcare. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2021;78(6):xxx-xxx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The Certainty of Uncertainty for a Global Supply Chain

Erin R. Fox, Pharm.D., BCPS, FASHP, Senior Director, Drug Information and Support Services, University of Utah Health, and Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Utah College of Pharmacy, Salt Lake City, UT

Aaron S. Kesselheim, M.D, J.D., M.P.H., Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Director, Program on Regulation, Therapeutics, And Law (PORTAL), Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA

Address correspondence to Dr. Fox (Erin.Fox@hsc.utah.edu).

INTRODUCTION

With a global pandemic and continuing uncertainty regarding the stability and quality of the medication supply chain, health-system pharmacists must be prepared for significant disruptions to “normal” healthcare delivery, including disruption of medication procurement.

ALLOCATION OF SCARCE RESOURCES

Drug shortages are not new to healthcare providers in the United States, and the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has highlighted the fragility of the global medication supply chain. The number of ongoing and active drug shortages increased from 202 in 2017 to 276 in 2020, with many of the shortages in 2020 exacerbated by the current pandemic.1

Primary management of shortages falls mainly to pharmacists. Forecast Panelists (FPs) overwhelmingly agreed (90%) that at least 75% of health systems will develop guidelines through ethics committees or similar processes to allocate finite resources during a disease pandemic (Figure 1, item 1). In the early days of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, as hospitals were struggling with allocation of personal protective equipment and ventilators, the crisis standards of care that states generated helped provide some clarity and transparency to the process. Bioethics researchers such as those at the Hastings Center and the Berman Institute are also suggesting guidance for allocating scarce resources.

Figure 1 (Global Supply Chain).

Forecast Panelists’ responses to the question, “How likely is it that the following will occur, by the year 2025, in the geographic region where you work?”

Most health systems suffered substantial financial shortfalls from fewer patient encounters and cancelled procedures during statewide shutdowns. While many FPs (81%) were optimistic that federal resources would be made available to hospitals for surge planning, early reporting has been disappointing (Figure 2, item 2). Substantial federal funds were provided to wealthy health systems, with 20 large chains receiving $5 billion in federal grants despite holding more than $100 billion in cash.2 Smaller hospitals, by contrast, received insufficient federal assistance.

MEDICATION QUALITY AND SUPPLY CHAIN

A key recommendation from a recent report by the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Drug Shortages Task Force was to develop a manufacturing quality rating system to provide incentives for drug manufacturers to invest in improving their facilities.3 Ratings would allow FDA to more clearly communicate differences between manufacturers in medication quality to health systems that purchase medications or to the public. Since 2013, FDA leaders have been advocating for such a system to reduce the likelihood of shortages and encourage low-performing manufacturers to improve.4 The FPs were almost evenly split on the question of whether FDA would rate the effectiveness of manufacturers’ quality management systems, with 47% agreeing and 53% disagreeing (Figure 1, item 4). Unfortunately, cases of quality problems, including with angiotensin II receptor blockers and metformin, have continued in recent years, sometimes also contributing to shortages. Despite several drug shortage provisions in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act),5 such as requiring manufacturers to provide FDA with more information regarding reasons for and durations of shortages and asking manufacturers to establish contingency plans relating to supply disruptions, a method to rate the quality of medications was not included.

A concern during the initial stages of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic was the global nature of the U.S. drug supply chain. Many clinicians were concerned that drug shortages would increase due to manufacturing closures in China or that some nations would halt imports to reserve supplies for their people. A list of potentially affected products was challenging to prepare due to the proprietary nature of much drug manufacturing information, including the source of raw materials and site or name of the manufacturer. FPs overwhelmingly (92%) believed that global issues such as trade restrictions, pandemics, or climate change will increase the potential for drug shortages (Figure 1, item 5).

Fortunately, supply line breakdowns due to global COVID-19-related closures did not come to pass. As more patients came down with COVID-19 in the United States, drug shortages increased, but those shortages were due to an increased demand resulting from high patient volumes rather than global causes. Despite this reality, politicians moved to bolster U.S. drug manufacturing. The U.S. Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) provided a $345 million contract to provide generic medications and the raw materials intended to produce medications needed to meet COVID-19-related demand.6 Congressional representatives also introduced multiple bills related to moving drug manufacturing back to the United States.

INTERNATIONAL MARKET AS A SOURCE OF LOWER DRUG PRICES

Despite potential concerns over a global supply chain, two-thirds of FPs (68%) believe the United States will adopt rules to import prescription drugs from other countries to help lower drug prices (Figure 1, item 6). The United States spends about $450 billion per year on prescription drugs and pays by far the most per capita for brand-name drugs in the world. Inexpensive generic drugs are among the most cost-effective healthcare interventions, and prices of some older, off-patent medications have been increased substantially, leading to increased healthcare system spending and lack of access for patients.

Importation of prescription drugs has been proposed for decades, but prior presidential administrations were reluctant to push for more vigorous implementation of importation in the face of opposition by the pharmaceutical industry. While importation of single-source brand-name drugs may not be feasible, FDA may develop pathways for responding to generic drug shortages (or price hikes) by facilitating the regulatory approval of overseas manufacturers of those products. Forty percent of generic medications without production competition in the United States had approved versions made by independent manufacturers outside of the United States, and importation could therefore help ensure lower prices.7

STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE LEADERS.

Develop or enhance your health system’s guidelines for allocating scarce pharmaceutical resources.

Collaborate with other health systems and local and state agencies to plan for pandemic-related surges or distribution of scarce resources such as vaccines. Establish information-sharing systems to ensure level loading between organizations.

Insist on receiving publicly reported quality measures when signing drug acquisition contracts, and ensure that contracts signed on behalf of health systems also include a measure of quality.

Encourage public policy advocates within your circle of influence (e.g., at your health system, within state and national hospital and pharmacy associations) to support legislation that reduces unnecessary spending on medications and improves the quality of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Disclosures

Dr. Fox is an unpaid volunteer member of the advisory board for Civica Rx and a member of the AJHP Editorial Advisory Board. The University of Utah Drug Information Service (UUDIS) has a contract to provide Vizient (a group purchasing organization) with drug shortage information. The total value of the contract represents less than 5% of the total budget for UUDIS.Dr. Fox also currently serves on the AJHP Editorial Advisory Board. Dr. Kesselheim’s work is funded by Arnold Ventures and the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science.

References

- 1. University of Utah Drug Information Service. Drug shortages statistics.https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Shortage-Resources/Drug-Shortages-Statistics (accessed September 4, 2020).

- 2. Drucker J, Silver-Greenberg J, Kliff S. Wealthiest hospitals got billions in bailout for struggling health providers (May 25, 2020). New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/25/business/coronavirus-hospitals-bailout.html (accessed August 13, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Food and Drug Administration. Report – drug shortages: root causes and potential solutions.https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-shortages/report-drug-shortages-root-causes-and-potential-solutions (accessed August 13, 2020).

- 4. Woodcock J, Wosinska M. Economic and technological drivers of generic sterile injectable drug shortages. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013; 93(2):170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. United States Senate. S 3548 Coronvirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/s3548/BILLS-116s3548is.pdf (accessed August 13, 2020).

- 6. Weintraub A. How Civica helped under-the-radar Phlow nab a $354M COVID-10 manufacturing deal (May 21, 2020). Fierce Pharma. https://www.fiercepharma.com/manufacturing/how-under-radar-phlow-and-civica-nabbed-a-354m-covid-19-manufacturing-deal (accessed August 13, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gupta R, Bollyky TJ, Cohen M, Ross JS, Kesselheim AS. Affordability and availability of off-patent drugs in the United States – the case for importing from abroad: observational study. BMJ. 2018; 360:k831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Access to Healthcare: Positioning Healthcare Systems for Improvement

Marie Chisholm-Burns, Pharm.D., M.P.H., M.B.A., FCCP, FASHP, FAST, Dean and Professor, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Pharmacy, and Professor of Surgery, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Medicine, Memphis, TN

Christopher K. Finch, Pharm.D., FCCM, FCCP, Chair and Professor, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Translational Science, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Pharmacy, Memphis, TN

Christina Spivey, Ph.D., LMSW, Associate Professor, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Translational Science, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Pharmacy, Memphis, TN

Address correspondence to Dr. Marie Chisholm-Burns (mchisho3@uthsc.edu).

INTRODUCTION

Barriers to healthcare threaten the health of those in front of the closed doors—and the health of everyone. Given the COVID-19 pandemic and the renewed awareness of health disparities in the United States, it is timely to discuss items pertaining to healthcare access, including utilization of telehealth services, pharmacy technicians and their role in medication access, legal regulations concerning pharmacists’ scope of practice, alignment of formulary decisions, and inpatient access to non-FDA-regulated therapies.

TELEHEALTH

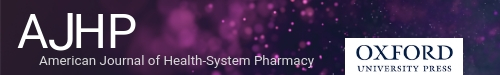

Greater than 90% of Forecast Panelists (FPs) expect significant expansion of patient access to telehealth in rural and other underserved locations, including use of telehealth to provide pharmacist patient care services and improve outcomes (Figure 2, items 1 and 2). Advances in technological adaptability will and have paved the way for this to occur. In fact, we have already witnessed a considerable growth in telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, with patient consultations being conducted remotely.1 Healthcare payers, such as Blue Cross Blue Shield, are expanding coverage (e.g., increasing reimbursement and waiving cost-sharing) for telehealth visits.1,2 Limited access to technology may be a potential barrier in some underserved populations and needs to be rectified. Nevertheless, use of telehealth, including telepharmacy (Figure 2, item 2), for services such as transitions of care and medication therapy monitoring and recommendations will likely continue to grow due to its convenience, efficiency, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness.

Figure 2 (Access to Healthcare).

Forecast Panelists’ responses to the question, “How likely is it that the following will occur, by the year 2025, in the geographic region where you work?”

SCOPE OF PRACTICE

Seventy-one percent of FPs believe that pharmacy technicians will be actively engaged with patients and interprofessional care teams in identifying, assessing, and resolving barriers to medication access (Figure 2, item 3). An interprofessional care team, which included pharmacy technicians, worked with patients to identify, assess, and resolve medication access barriers; increase medication access; and significantly improve therapeutic outcomes and patient quality of life.3

Although 29% of FPs believe it is not likely that pharmacy technicians will take on this expanded role, with adequate training pharmacy technicians can successfully perform beyond traditional dispensing support roles. It is incumbent upon pharmacy leaders to assess the roles pharmacy technicians can play, as extending their scope of practice may improve care and reduce costs to institutions and the patients they serve.

Ninety-one percent of FPs believe 50% of states will have a legal provision through which pharmacist scope of practice can be expanded when public health emergencies are declared (Figure 2, item 4), as was seen in 2009 during the H1N1 pandemic with increased authorization of pharmacists to administer the H1N1 vaccine.4 Likewise, in response to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act authorized licensed pharmacists to order and perform COVID-19 tests and limited the authority of state agencies to prevent distribution of tests by pharmacists.5 With immunization administration and point-of-care testing by pharmacists becoming more commonplace, the expansion of scope of practice, including prescribing authority and more comprehensive medication management, during public health emergencies is a natural step forward in the best interests of public health.

FORMULARY ALIGNMENT

FPs were divided on whether at least 25% of health systems will align their inpatient drug formularies with the formularies of other health systems, insurers, and health plans that serve their region (Figure 2, item 5). While having seamless transitions from one setting to the next as they relate to medication therapy would be ideal, the reality of having a perfectly aligned formulary is rife with logistical challenges, including:

Lack of national formulary guideline adoption

Medication shortages

Prescriber preferences

Wholesaler and/or group purchasing organization contracts, discounts, and preferred products

Direct-to-consumer advertising

Tertiary care hospitals’ different formulary needs relative to community hospitals, which provide more general care

Variation in patient insurance medication coverage

Inconsistencies among insurers and reimbursement models

Given these challenges and many more, the realization of a community or regional formulary will continue to face obstacles and likely not be fully supported in the near future.

NON-FDA-REGULATED THERAPIES

The majority of FPs do not believe that at least 75% of health systems’ policies will allow inpatients broadened access to non-FDA-regulated therapies (Figure 2, item 6), likely due to concerns regarding liability and uncertainty as to the lack of regulatory standards, safety, and efficacy of these products. For example, since cannabis use is illegal under federal law and because hospital accreditation occurs through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, health systems that provide access to cannabis put themselves at significant risk, as cannabis use could result in violations, loss of federal funding, or other substantial penalties.6 Although at least 50% of respondents in pediatric inpatient settings permitted home herbal preparations and supplements, adverse events have resulted from use of supplements.7 Universal screening of home products by institutional pharmacies is needed to reduce potential risks posed by these products,7 but screening may be prohibitive due to resource limitations in health systems. The Joint Commission weighed in on nonhospital medications with standard MM.03.01.05, which states, “the hospital safely controls medications brought into the hospital by patients, their families, or licensed independent practitioners.” 8 Thus, allowing these products into the health system brings additional pharmacy responsibilities: physical inspection and verification of home product and ingredients, manual entry into the medication administration record, drug interaction checking, product storage, and special labeling for barcode-assisted medication administration. In addition, if inpatient settings began dispensing non-FDA-regulated products, added problems would no doubt materialize in the form of lack of inventory control and formulary management. All of these pose opportunities for error, increased cost, and breaches in safety for the patient.

STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE LEADERS.

Build on the expanded use of telehealth during the coronavirus pandemic to implement, permanently, telepharmacy that will enhance the medication-related outcomes of all patients in your health system, including those in underserved areas.

Assess how pharmacy technicians in your pharmacy enterprise can be engaged more broadly and effectively by patient care teams to improve medication access; enhance technician training and roles accordingly.

Evaluate with other pharmacy leaders in your state the desirability and feasibility of making permanent any expanded pharmacy scope of practice that was implemented in response to the coronavirus pandemic or other public health emergencies.

Pursue with the pharmacy leaders of other health systems in your region the prospect for greater harmonization of formularies and the formulary decision-making process.

Initiate a process within your health system of examining (and revising if necessary) existing policies related to use of non-FDA-regulated therapies.

Disclosures

The authors have declared no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Engel-Smith L. COVID breathes life into North Carolina’s rural telehealth, but broadband remains an obstacle. North Carolina Health News. Published May 14, 2020. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.northcarolinahealthnews.org/2020/05/14/coronavirus-rural-telehealth/ [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. Media statement: Blue Cross and Blue Shield Companies announce coverage of telehealth services for members. Published March 19, 2020. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.bcbs.com/press-releases/media-statement-blue-cross-and-blue-shield-companies-announce-coverage-of-telehealth-services-for-members

- 3. Chisholm MA, Spivey CA, Mulloy LL. Effects of a medication assistance program with medication therapy management on the health of renal transplant recipients. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2007; 64:1506-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Courtney B, Morhard R, Bouri Net al. . Expanding practitioner scopes of practice during public health emergencies: Experiences from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic vaccination efforts. Biosecur Bioterror. 2010; 8:223-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charrow RP. Advisory opinion 20-02 on the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act and the secretary’s declaration under the act. Published May 19, 2020. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/advisory-opinion-20-02-hhs-ogc-prep-act.pdf

- 6. Borgelt LM, Franson KL. Considerations for hospital policies regardig medical cannabis use. Hosp Pharm. 2017; 52:89-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stubblefield S. Survey of complementary and alternative medicine in pediatric inpatient settings. Complementary Ther Med. 2017; 35:20-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Standard MM. 03.01.05. In: Comprehensive Medication Manual for Hospitals: The Official Handbook, Update 2 (CAMH). Joint Commission; 2011. [Google Scholar]

Pharmacy Analytics and Use of Big Data

Jannet M. Carmichael, B.S., Pharm.D., BCPS, President, Pharm Consult NV LLC, Reno, NV

Joy Meier, Pharm.D., PA, BCACP, Chief Health Informatics Officer, VA Sierra Pacific Network, Pleasant Hill, CA

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacists are uniquely qualified and inherently responsible for assuming a significant role in pharmacy data analytics.1 Most health systems have focused on health information technology (HIT) installation and data storage, which includes advanced clinical systems, electronic health records, business intelligence, and analytics tools—the “things” that collect the data.2 The time has come to place more emphasis on the output of these systems and harness this vast knowledge through the analysis, use, and dissemination of that data. Integrating an informatics pharmacist as a core team member enhances the likelihood that big data will be used for administrative and clinical decision making.3

Pharmacy informatics, as defined by the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), focuses on medication-related data and knowledge within the continuum of healthcare systems—including its acquisition, storage, analysis, use and dissemination—in the delivery of optimal medication-related patient care and health outcomes.2 HIT and health informatics (HI) are not separate from pharmacy operations and clinical pharmacy (i.e., they do not constitute a “third pillar”), as some have suggested.4 In fact, more emphasis should be put on integrating pharmacy analytics, defined as the leveraging and use of data from HIT systems, to optimize clinical practice outcomes and drive innovation within pharmacy operations. Big data analytics and use empower healthcare systems to strategically support cost-efficient evidence-based decisions and improve individual and population health and outcomes.

HEALTH SYSTEMS’ USE OF BIG DATA

Along with data usage for clinical and administrative purposes, health systems will be confronted with use cases that will present both ethical and legal challenges. For example, employee-related data may be collected and analyzed for quality improvement within the institution, but at the same time employee privacy should be protected. Survey items 1 and 2 relate to use of electronic surveillance technology to track the location and activities of workers for the purpose of performance evaluation and the development of policies that protect personal-privacy rights of employees while they are being tracked. The amount of time a clinician spends in each patient’s electronic health record (EHR) or communicating with another health professional is already tracked within EHR systems. Forecast Panelists (FPs) had a split response regarding the likelihood of electronic surveillance being used for performance evaluation (Figure 3, item 1). Use of this information for employee contact tracing during a pandemic, or to improve work-flow, may be more helpful than punitive. FPs were split on whether health systems will have policies that protect personal-privacy rights of employees associated with electronic surveillance (Figure 3, item 2). No doubt these policies will be affected by societal and ethical concerns about human surveillance by authorities, be they governments, businesses, or employers.

Figure 3 (Analytics and Big Data).

Forecast Panelists’ responses to the question, “How likely is it that the following will occur, by the year 2025, in the geographic region where you work?”

Two-thirds of FPs thought that over the next 5 years health systems would prohibit the sale of aggregated, de-identified patient and provider data to third parties (Figure 3, item 3). While there are few technical limitations to information exchange in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act or regulations, many health systems see health information as proprietary and may not wish to share data from their EHR with other pharmacists or providers of care outside the health system.4 There may be few reasons to share provider data for marketing purposes, but there are many potential benefits to data standardization, exchange, and stewardship to improve patient outcomes and decrease costs. Regulatory involvement may be needed to standardize and provide the level playing field needed for all systems to participate equally in data sharing.

HI PHARMACIST ENGAGEMENT

Most FPs indicated that analytics will be routinely used to leverage population level data for prioritizing patients for pharmacist care (Figure 3, item 4). This may be based on the knowledge that hospitals and health systems cannot afford to provide pharmacist-review of every medication treatment order. Pharmacy informaticists’ guidance on how to apply population-level data efficiently will be essential. Sophisticated algorithms are being developed through the use of machine learning and artificial intelligence, and 73% of FPs anticipate EHR data will be used to compute optimal drug dosages and individualize therapies to patient-specific variables (Figure 3, item 5). It remains to be seen whether this approach will be applied broadly to all drug doses or limited to high-risk therapies. Likewise, 69% of FPs believe it likely that algorithms applied within the EHR will detect instances when a medication order deviates from the institution’s “historical” pattern of use (Figure 3, item 6). Such systems should prioritize “evidence-based” recommendations over historic patterns of use. Pharmacist HI professionals will be needed to assign parameters to develop, analyze, and support these clinical decision tools and further analyze the effects of their use on outcomes.

STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE LEADERS.

Recruit, resource, and expand\ a team of pharmacist HI professionals with strong clinical decision-making skills. pharmacists trained to make appropriate evidence-based decisions for individual patients are prerequisite to designing systems for hundreds or thousands through computer algorithms. Ensure that these professionals contribute far beyond the installation and integration of computer hardware and software for HIT systems, and include training in the ability to analyze and use data.

Ensure that pharmacy HI professionals work collaboratively with other HI professionals throughout the health-system to identify clinical and ethical issues related to patients and employees. Pharmacy HI professions should have the competence and capability to evaluate commercial applications of artificial intelligence and identify problems or issues in the medication-use process that merit development of an artificial intelligence application internally.

Engage in implementation, analysis, and utilization of big data that supports all aspects of patient care across multiple hospital systems and requirements for data sharing. Analytics and patient outcomes should drive the strategic direction of pharmacy operations and clinical pharmacy service decisions, as well as safe and evidence-based medication use throughout the healthcare system.

Incorporate advanced sets of core knowledge into pharmacy informatics residency training that include design, analysis, use, and evaluation of data to improve clinical and population health processes and outcomes, enhance patient and health professional interactions with the health system, and strengthen the ability of communities and individuals to manage their health.5

Create new pharmacy service offerings (e.g., granular, interactive data-driven dashboards of actual clinical care outcomes) that provide evidence-based medication use guidance to healthcare providers in all service areas, that remove barriers, and that improve patient outcomes and medication use.

Promote organizational learning to better understand the opportunities and limitations of the institution’s big data. As analytic processes develop and mature, ensure that clinical and operational outcomes are assessed for effectiveness and beneficial impact.

Disclosures

Dr. Carmichael currently serves on the AJHP Editorial Advisory Board. Dr. Meier has declared no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on the pharmacist’s role in clinical informatics. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2016; 73:410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. HIMSS: Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society. Accessed June 20, 2020. www.himss.org

- 3. Matsuura GT, Weeks DL. Use of pharmacy informatics resources by clinical pharmacy services in acute care hospitals. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2009; 66:1934-8. 10.2146/ajhp080534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Belford S, Peters SG. Technology innovations and involvement by pharmacy leaders. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2019; 76:89-91. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gadd CS, Steen EB, Caro CM, Greenberg S, Williams JJ, Fridsma DB. Domains, tasks, and knowledge for health informatics practice: results of a practice analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020; 27:845-52. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Healthcare Financing and Delivery: Leading Through Uncertainty

Thomas Woller, M.S., FASHP, System Vice President, Pharmacy Services, Advocate Aurora Health, Waukesha, WI

Brian Pinto, Pharm.D., M.B.A., Senior Principal, Government Affairs, Cigna, Washington DC

Address correspondence to Mr. Woller (tom.woller@aah.org).

INTRODUCTION

Like many other aspects of medical care, healthcare financing and delivery was affected immediately by the COVID-19 pandemic. Federal and state governments diverted much of their attention to respond to the pandemic, resulting in less focus on other issues facing healthcare. Likewise, providers, suppliers, and payers (pharmacy benefit managers [PBMs] and insurance companies) had to set aside work being done on issues such as drug pricing reform to address the pandemic. 2020 began with significant uncertainty regarding the 6 questions posed to Forecast Panelists (FPs). The pandemic response, coupled with election year politics, has layered additional complexity on the environment, leaving pharmacy leaders with uncertainty as they navigate the future.

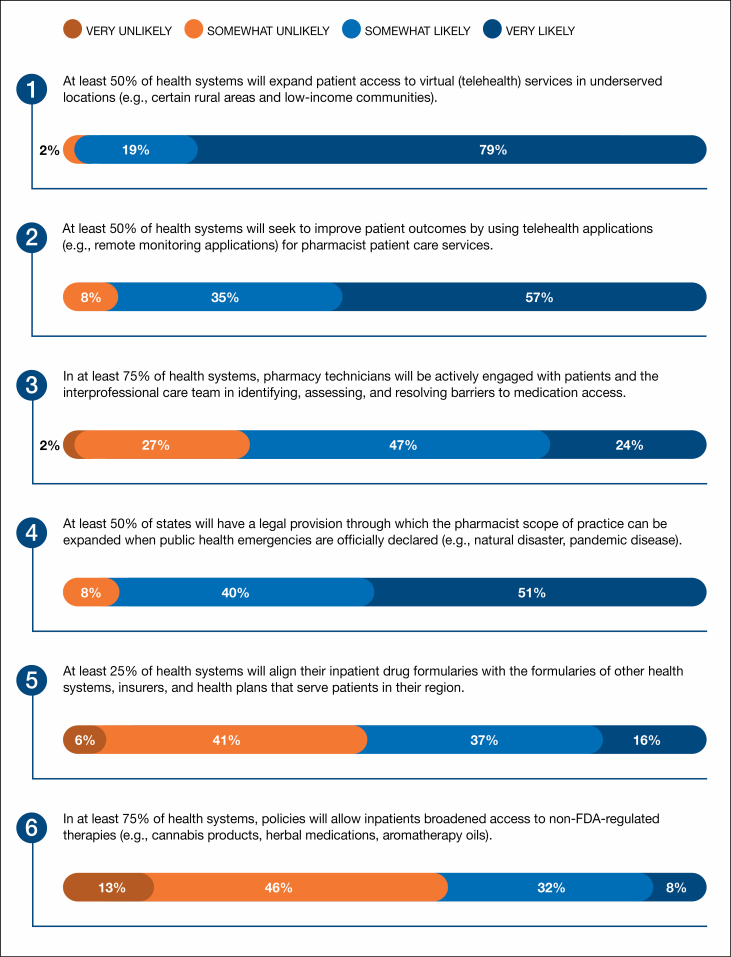

PBM PRICE TRANSPARENCY

There is growing interest in drug pricing reform at both the federal and state levels.1 FPs were in general agreement that the trend of state government intervention to require price transparency by PBMs will continue (Figure 4, item 1). However, it is worth noting that price transparency reform is not limited to PBMs or drug costs. Hospitals and insurers are also under significant pressure for price transparency, as evidenced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services proposed rule issued at the end of 2019.2 Pharmacy leaders should continue to nurture relationships with government affairs (GA) leaders in their health systems by scheduling regular meetings with GA representatives, establishing a pharmacy advocacy platform, and advocating for comprehensive legislative strategies that improve access to and affordability of prescription medications.

Figure 4 (Healthcare Financing and Delivery).

Forecast Panelists’ responses to the question, “How likely is it that the following will occur, by the year 2025, in the geographic region where you work?”

LONG-TERM CONTRACTS FOR DRUG SUPPLIES

The past 3 years have seen a sea change in terms of contracting for multisource injectable drugs. Group purchasing organizations (GPOs) and other entities have begun using long-term contracts to assure supply of these critical medications. Seventy-five percent of FPs believe that 50% or more of the generic injectable drugs used by health systems in the future will be acquired through these long-term contracts (Figure 4, item 2). This strategy could result in a much more stable supply chain for these products. Pharmacy leaders should evaluate contracting opportunities in terms of cost, supply stability, and risk of failure to supply. To mitigate the risk of shortages, a comprehensive pharmacy supply chain strategy should include multiple channels for key products whenever possible.

VALUE-BASED AGREEMENTS FOR SPECIALTY DRUGS

The survey item in this section of the Forecast that had the most FP agreement was the statement “At least 25% of health systems will execute five or more value-based contracts for specialty drugs” (Figure 4, item 3); 84% of FPs indicated this was either very or somewhat likely. To date, most health plans and PBMs have implemented value-based agreements (VBAs) with pharmaceutical manufacturers, albeit with limited success.3 The lack of uptake of VBAs is multifactorial, but some of the barriers include concerns with Medicaid “best price” (BP), clinical outcome definitions, and a process to track patient outcomes over time. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is attempting to address some of these variables in its recent proposed rule that would change how manufacturers calculate BP and average manufacturer price.4 If finalized, the proposed rule could lead to states, payers, and health systems engaging in more value-based purchasing contracts with pharmaceutical manufacturers. Additionally, as health systems take on more risk under accountable care organization or similar arrangements, pharmacy leaders should evaluate the use of value-based contracts to improve clinical effectiveness of medication use.

CHARITY-CARE REQUIREMENTS FOR PRIVATE, NONPROFIT HOSPITALS

In the years leading up to 2020 there was growing interest in examining the financial performance of health systems, executive compensation and the tax-exempt status of hospitals and health systems.5,6 In the 2020 Forecast survey, only 12% of FPs said it was very likely that federal and state governments would strengthen charity-care requirements for private, not-for-profit health systems. The pandemic response has resulted in significant short-term financial pressures7 for health systems while shining a light on the importance of maintaining the infrastructure of our healthcare system. The combination of high public opinion of healthcare workers and financial losses for health systems may temporarily reduce the likelihood of state and federal government actions that would financially harm health systems. However, regulatory action that will harm health systems has advanced, including proposed payment reductions. The results of the 2020 national elections and pandemic response are likely to have an impact on the likelihood that there will be specific legislative action addressing the tax-exempt status of hospitals and health systems.

EXTERNAL PARTNERSHIPS FOR DRUG SUPPLIES AND ALTERNATE MEDICINE PROVIDERS

All participants in the pharmacy supply chain are compelled to provide value. Failure to do so will threaten the very existence of any participant as nontraditional entrants continually survey the environment looking for opportunities to disrupt the market. That is the backdrop for 2 questions in this year’s survey. The first question is about the likelihood that external partnerships could provide alternatives to the traditional wholesale distribution of drugs. FPs were split in their views about the prospects of this happening, with 56% believing it likely and 44% believing it unlikely (Figure 4, item 5). The second question addresses the notion that alternate providers of medicines will capture 25% of the consumer prescription market; 78% of respondents thought that this is at least somewhat likely to occur (Figure 4, item 6). That more than half of the FPs responded affirmatively to both questions is enough to raise questions about the possibility of significant disruption among the primary players in the pharmacy supply chain: manufacturers, PBMs, wholesalers, GPOs, and pharmacies.

Health systems are challenged now more than ever to provide revenue-generating services through innovative channels that may require external partnerships with nontraditional health companies and even potential competitors. A majority of survey respondents believe that this may occur with external partners that provide alternatives to traditional wholesale drug distribution services. The advent of gene-based therapies over the past few decades has spurred disruption in the traditional pharmacy supply chain.

Pharmacy leaders should remain vigilant with respect to external arrangements and the impact of partnerships on other elements of the supply chain. Additionally, continued attention should be paid to the value health-system pharmacy is bringing both financially and clinically. Patient care should remain the hallmark of strategic planning for pharmacy leaders. Consideration of the potential for competitors to displace some or all aspects of a health-system pharmacy operation can be an effective tool for long-term planning.

STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE LEADERS.

Establish and foster close relationships with health-system government affairs teams, jointly establishing a pharmacy policy platform that can be used to advocate at the state and national levels. Pharmacy leaders should proactively influence the overall health-system policy platform whenever possible and be poised to react whenever necessary.

Carefully monitor trends in the drug contracting and fulfillment environment. Pharmacy supply chain leaders should partner with health-system supply chain leaders to jointly assess unique contracting opportunities. Multiple supply channels for critical drugs should be established whenever possible.

Acquire a deep understanding of the financial performance and position of the healthcare system. Fostering strong relationships with system finance leaders allows pharmacy leaders to establish plans that are in tune with the organization and increases the likelihood of success.

Exhaustively evaluate every aspect of the pharmacy enterprise with respect to value offered to the patient and the system. Consider alternative ways that the service or product might be offered by competitors (internal and external) in the future.

Disclosures

The authors have declared no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. PBM Watch. Pharmacy benefit manager legislation. Accessed July 17, 2020. http://www.pbmwatch.com/pbm-legislation.html

- 2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Transparency in coverage proposed rule (CMS- 9915 –P) (Nov 15, 2019). Published Nov 15, 2019. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/transparency-coverage-proposed-rule-cms-9915-p

- 3. American Health & Drug Benefits. Value-based agreements in healthcare: willingness versus ability. Accessed July 17, 2020. http://www.ahdbonline.com/issues/2019/september-2019-vol-12-no-5/2843-value-based-agreements-in-healthcare-willingness-versus-ability [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid program; establishing minimum standards in Medicaid state drug utilization review (DUR) and supporting value-based purchasing (VBP) for drugs covered in Medicaid, revising Medicaid drug rebate and third party liability (TPL) requirements. Published June 19, 2020. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/06/19/2020–12970/medicaid-program-establishing-minimum-standards-in-medicaid-state-drug-utilization-review-dur-and

- 5. LaPointe JA. Top-earning non-profit hospitals offer less charity care. Revcycle Intelligence. Published February 18, 2020. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/top-earning-non-profit-hospitals-offer-less-charity-care [Google Scholar]

- 6. Advisory Board. There’s a big gap in how much charity care nonprofit hospitals provide, a study finds. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2020/02/20/charity-care

- 7. American Hospital Association. New AHA report finds losses deepen for hospitals and health systems due to COVID-19. Published June 2020. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://www.aha.org/issue-brief/2020-06-30-new-aha-report-finds-losses-deepen-hospitals-and-health-systems-due-covid-19

Patient Safety: New Frontiers for Pharmacists

David W. Bates, M.D., Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, and Chief of General Internal Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA

James M. Hoffman, Pharm.D., M.S., Chief Patient Safety Officer and Associate Member, Pharmaceutical Sciences, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN

Address correspondence to Dr. Hoffman (james.hoffman@stjude.org).

INTRODUCTION

Improving patient safety has been a longstanding priority for which pharmacists are ideally suited to lead. Pharmacists widely share this focus on patient safety, but the maturity of medication-use safety efforts varies across hospitals and health systems. Compared to other areas of focus for patient safety, the medication-use system in health systems consistently marches toward greater complexity through new knowledge, drug approvals, new technology, the supply chain, reimbursement pressures, and many other factors. Therefore, even pharmacists with the most sophisticated programs always have new opportunities to improve medication safety through a clear vision, effective use of the formulary system, staff support, and leadership.

PREVENTABLE HARM FROM MEDICATION USE: AN INTRACTABLE PROBLEM OR LIMITED VISION?

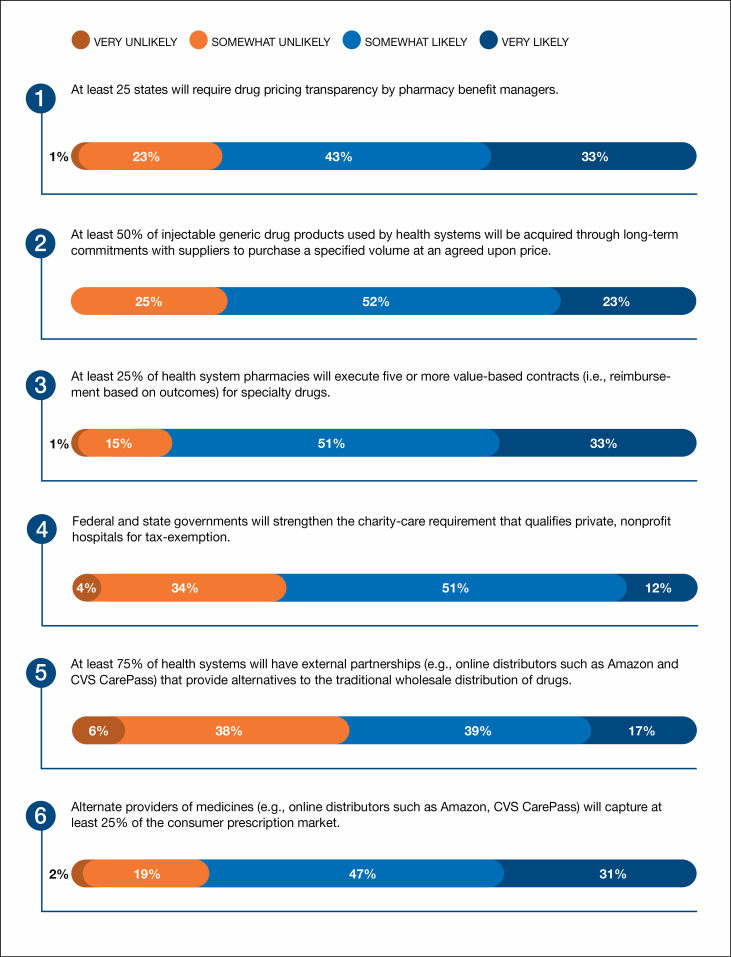

Among Forecast Panelists (FPs), 82% responded that it was very or somewhat unlikely that preventable harm from medications will become nonexistent or rare (Figure 5, item 1). Thus, pharmacists may accept a level of harm from medications as inevitable. This view contrasts with a vision of “zero preventable harm” that is a goal in a growing number of health systems.1 Some hospitals put great emphasis on zero harm through communications to staff and the public. Proponents of this approach often point to success in reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) through checklists, bundles, and other interventions. However, while the reductions in CLABSI and CAUTI are great accomplishments for patient safety, these conditions do not have the same complexity or constant change of the medication-use process. The “zero harm paradigm” represents a convenient mechanism to rally attention to harm reduction, and it can prompt new thinking to propel an organization’s patient safety efforts forward. However, an unrelenting focus on zero harm (or “absolute safety”) also brings risks, including demoralizing clinicians, not being measurable, and placing too much focus on harm to the detriment of holistically considering all risks to patient care.2 FPs may have been considering these nuances in answering this item.

Figure 5 (Patient Safety).

Forecast Panelists’ responses to the question, “How likely is it that the following will occur, by the year 2025, in the geographic region where you work?”

Ultimately, a bold vision for patient safety must be articulated with clear and measurable deliverables, but we do not believe this requires a zero harm message, especially for medication use, which is constantly changing. Pharmacists must succinctly articulate the multifaceted risks for patient harm from medications to physicians, other clinician colleagues, and health-system leaders. Patient safety vision must be coupled with pragmatic action and meaningful measurement to understand progress, and patient safety measurement needs further development.3 The evaluation of safe medication use must retain a holistic view across systems and processes to identify and mitigate risks that will ultimately reduce patient harm.

EVALUATING NEW MEDICATIONS AND MAINTAINING THE INTEGRITY OF THE FORMULARY SYSTEM

The underlying evidence used by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve medications has evolved to use fewer data and new study designs.4 Comparative data are often unavailable, and passage of the 21st Century Cures Act in 2016 has enabled FDA approvals using a range of data from observational studies.5,6 The global COVID-19 pandemic has brought pressure to use a variety of new therapies with little or no evidence from randomized studies. With Forecast survey data collected just as the COVID-19 outbreak was developing, 59% of FPs thought it was very or somewhat likely that health systems’ pharmacy and therapeutics committees will devote significantly more time assessing the safety and efficacy of new medications because of relaxed FDA requirements for product approval (Figure 5, item 2). The formulary system represents a mechanism to promote safe and appropriate medication use across a health system, and these functions must remain focused on its fundamental role to review the evidence for new medications.7

Health systems should continue to use the formulary system to provide oversight of opioid prescribing patterns and support treatment for opioid use disorder. The risk for opioid misuse is clear, and FPs thought it was likely these issues would be addressed at the health-system level (Figure 5, item 3) and through changes in federal regulations (Figure 5, item 4).

STAFF RESILIENCE AND SAFE PATIENT CARE

Most FPs (76%) thought it was somewhat or very likely that in 75% of health systems, the pharmacy department will have an active program to support the well-being and resiliency of its staff (Figure 5, item 5). Supporting staff is central to patient safety. If staff well-being is not supported, then staff cannot provide the safest possible patient care. Many staff well-being programs already exist in health systems, including some that emanated from pharmacy departments.8 Appropriately, these efforts are maturing from a relatively narrow initial focus on specific patient events to broader staff support resources to address many aspects of working in healthcare. With the manifold pressures from the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for these resources has only grown.

NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR LEADERSHIP

FPs were optimistic that in at least 50% of health systems, a pharmacist will be in an enterprise-wide patient safety leadership role, with 77% believing it very or somewhat likely (Figure 5, item 6). This observation is consistent with the 2020 Pharmacy Forecast, in which FPs indicated it was likely that pharmacy leaders would take on broader roles by supervising additional departments. Building on broad clinical knowledge, leadership skills, and experience collaborating across the health system to enact change, several pharmacists have successfully taken on such roles. Further, pharmacists have the fundamental knowledge of the medication-use system, with improving medication safety as a core competency, which they can build upon to embrace leadership in other aspects of patient safety in health systems. Because the medication-use system crosses many disciplines and involves a variety of aspects of a health system’s operations, it is natural for a pharmacist patient safety leader to systematically consider every aspect of a patient safety event or proactive risk assessment.

STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PHARMACY LEADERS.

Advocate for a pharmacist to be placed in an organization-wide role with corresponding authority to provide strategic leadership for medication use and patient safety.

Identify new medication safety priorities by asking provocative questions on how harm can be eliminated, and convert these ideas into strategic plans with defined objectives and a corresponding measurement approach.

Ensure pharmacists are actively engaged in setting health-system patient safety priorities to identify medication safety goals and be positioned to make contributions to patient safety beyond the medication-use process.

Develop new patient safety measures and monitoring strategies to identify medication safety risks and reduce patient harm from medications.

Use the formulary system to systematically identify the quality and quantity of evidence used to approve new medications and implement additional monitoring, conditional approval, or other steps when evidence is deemed to be inadequate.

Regardless of the specific support resources available in your health system, remain vigilant and consider specific actions for the well-being needs of pharmacy team members in the strategic planning process.

Disclosures

Dr. Hoffman currently serves on the AJHP Editorial Advisory Board. Dr. Bates has declared no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Chassin MR, Loeb JM. High-reliability health care: getting there from here. Milbank Q. 2013; 91(3):459-90. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomas EJ. The harms of promoting ‘Zero Harm’. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020; 29(1):4-6. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bates DW, Singh H. Two decades since To Err Is Human: an assessment of progress and emerging priorities in patient safety. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018; 37(11):1736-43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Darrow JJ, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. FDA approval and regulation of pharmaceuticals, 1983–2018. JAMA. 2020; 323(2):164-76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Naci H, Salcher-Konrad M, Kesselheim ASet al. . Generating comparative evidence on new drugs and devices before approval [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Jun 27; 395(10242):1972]. Lancet. 2020; 395(10228):986-97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33178-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kesselheim AS, Avorn J. New “21st Century Cures” legislation: speed and ease vs science. JAMA. 2017; 317(6):581-2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tyler LS, Cole SW, May JRet al. . ASHP guidelines on the pharmacy and therapeutics committee and the formulary system. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008; 65(13):1272-83. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krzan KD, Merandi J, Morvay S, Mirtallo J. Implementation of a “second victim” program in a pediatric hospital. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2015; 72(7):563-7. doi: 10.2146/ajhp140650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scope of the Pharmacy Enterprise: From Volume to Value

John A. Armitstead, M.S., RPh, FASHP, System Director of Pharmacy, Lee Health, Fort Myers, FL

Dorinda Segovia, PharmD, MBA, Vice President Pharmacy Services, Memorial Healthcare System, Hollywood, FL

Address correspondence to Dr. DiPiro (jtdipiro@vcu.edu).

The movement from volume to value reimbursement models in healthcare systems has been driving the pharmacy enterprise to focus on preventive medicine and accountability of healthcare outcomes far beyond the traditional role of hospital-based acute care.1 Payment models are moving toward valuing effective medication use versus traditional models of paying for medication consumption.2 Pharmacists are patient care experts with skills to lead in this challenge of providing optimal medication value.

ACCESS TO PHARMACISTS

Most (76%) Forecast Panelists (FPs) agreed that pharmacists will likely play a significant role in addressing the scarcity of primary care services (Figure 6, item 1) in remote and underserved areas. Coverage limitations or no insurance and service availability remain an issue for Americans, and healthcare access remains at the top of the healthcare agenda.

Figure 6 (Scope of the Pharmacy Enterpise).

Forecast Panelists’ responses to the question, “How likely is it that the following will occur, by the year 2025, in the geographic region where you work?”

Many health systems have already achieved improved patient outcomes by placing pharmacists in primary care settings to provide comprehensive medication management, integrate care plans, and educate patients and providers on medication use, including adherence.3-5 Expanding the pharmacist’s role in primary care is a natural step to meet care access needs of underserved populations. Legislation in many states grants pharmacists provider status, permitting collaborative practice agreements and making pharmacists’ leadership in access expansion possible. The integrated presence of pharmacists as part of clinician teams will continue as the roles solidify, funding sources are identified, and commercial, state, and federal payers reimburse for these population health services.

REDEPLOYMENT OF ACUTE CARE POSITIONS

FPs were split (57% to 43%) on the likelihood of acute care pharmacist positions being redeployed to areas such as ambulatory care, population health, specialty pharmacy, and home care (Figure 6, item 2). However, health systems will likely continue to expand their services in non-acute-care areas, and more pharmacists will practice in these areas.

To what extent will pharmacist positions come from reductions in force in acute care vs being new ambulatory care hires? This will depend on the extent of contraction in acute care services or how extensively acute care pharmacists integrate transitions of care activities into their roles.

The emphasis on chronic disease state management by payers across the continuum of care, coupled with population health initiatives and pressures to move away from treating acute-episodic events will result in expansion of pharmacists in ambulatory settings.6 With expansion in ambulatory care roles, workforce adjustments will be required, including justifying positions and/or expansion of technician roles to meet the demands of the pharmacy enterprise.

BEYOND MEDICATION RECONCILIATION

A large majority of FPs (77%) agreed that the pharmacy staff will reconcile medications during care transitions (Figure 6, item 3). An accurate and comprehensive medication history upon admission is essential to the medication reconciliation processes, and its benefits are well documented in the literature.7,8 One indisputable success of ASHP’s Practice Advancement Initiative (PAI)7 is identification of the vital role pharmacy professionals have in assuring medication reconciliation accuracy across all care transitions.

The pharmacy team is uniquely positioned to facilitate transitions through all levels of care, thanks to their knowledge of drug and dosage form availability, formulary mechanics, patient medication assistance programs, and access to the claim adjudication process. Assuring that drug therapy plans are accurate and understood by the patient are critical in avoiding medication-related readmissions.

DOCUMENTATION OF CARE

Availability of pharmacist documentation of patient care for all members of the healthcare team was rated as likely or somewhat likely to occur by 90% of FPs (Figure 6, item 4).

Pharmacists’ drug therapy and plan of care assessments designed to ensure safe and effective use of drugs must be available to all healthcare team members. Although there is a well-established interdisciplinary documentation standard within the inpatient hospital environment, there are opportunities for pharmacists’ transparent documentation of a patient’s care. The keys to success in pharmacist documentation are developing methods by which pharmacists’ therapeutic and monitoring recommendations can be made available in the comprehensive record.

TEAM CARE FOR COMPLEX MEDICATION MANAGEMENT

There was wide agreement by FPs (Figure 6, item 5) that pharmacists will routinely care for patients with complex medication-related needs, with accountability for patient care outcomes. Complex medication management is clearly an opportunity for pharmacists to achieve optimal patient health outcomes. The pharmacist’s role in complex medication management should include a wide range of patient services focused on medications, including ongoing patient assessment, development of a personalized comprehensive medication-use plan, care coordination, medication and disease state monitoring, and wellness and preventive services.

CREDENTIALING AND PRIVILEGING

Seventy-five percent of FPs agreed that credentialing and privileging in health systems will increase (Figure 6, item 6). Privileging will be critical as specialized education, training, and competencies are and continue to be required in advanced practice. The credentialing and privileging processes must ensure that pharmacists being deployed to advanced care settings have attained the qualifications to practice in those settings.9

Pharmacists providing advanced services, with coinciding responsibility and accountability for patient out-comes, must be properly credentialed and privileged to perform the advanced practices.

STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PHARMACY LEADERS.

Actively develop a strategic plan to pursue opportunities for pharmacy enterprise expansion into ambulatory sites and telehealth settings including underserved and remote areas, where access to a pharmacist can be assured for all patients.

Plan for acute care pharmacists to provide transitions of care medication services connecting patients with their ambulatory care pharmacists, including in self-care, community pharmacy, home care, and specialty pharmacy, as well as skilled nursing facility settings, where access and affordability to medication therapy can be assured.

Provide medication reconciliation services to all patients in the health system to assure that medication accuracy is assured.

Assure that documentation of pharmacists services are in the patient electronic healthcare record and that such documentation is available to all healthcare providers across the continuum of care.

Develop comprehensive medication management services by pharmacists for patients in high-risk and chronic disease states in which medication management is a key for optimal patient outcomes.

Define the roles of the pharmacist in ambulatory and population health management while assuring that pharmacists have the credentials, privileges, and competencies to provide advanced care.

Disclosures

The authors have declared no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Schenkat D, Rough S, Hansen A, Chen D, Knoer SJ. Creating organizational value by leveraging the multihospital pharmacy enterprise. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2018; 75:437-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abramowitz PW, Chen DF, Cobaugh DJ. Multihospital health systems: growing complexity of pharmacy enterprise brings opportunities and challenges. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2018; 75:417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Epplen KT. Patient care delivery and integration: stimulating advancement of ambulatory care pharmacy practice in an era of healthcare reform. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2014; 71:357-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Helling D, Johnson SG. Defining and advancing ambulatory care pharmacy services: It is time to lengthen our stride. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2014; 71(16):1348-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Homsted F, Chen DF, Knoer SJ. Building value: Expanding ambulatory care in the pharmacy enterprise. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2016; 73(10):635-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones L, Grescovic G, Grassi DMet al. . Medication therapy disease management: Geisinger’s approach to population health management. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2017; 74(18): 1422-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Society of Health System Pharmacists. PAI 2030. Accessed August 22, 2020. https://www.ashp.org/Pharmacy-Practice/PAI

- 8. Mueller SK, Cunningham Sponsler K, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices. Arch Intern Med. 2012; 174(14):1057-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. American Society of Health System Pharmacists. Credentialing and privileging of pharmacists: a resource paper from the Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2014; 71(21):1891-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The Pharmacy Workforce: The Need to Recalibrate Supply and Demand and Leverage Prescribing, Technology, and Pharmacy Technicians to Advance the Practice of Pharmacy

Melanie A. Dodd, Pharm.D., Ph.C., BCPS, FASHP, Associate Dean for Clinical Affairs and Associate Professor, The University of New Mexico College of Pharmacy, Albuquerque, NM

Mollie Ashe Scott, Pharm.D., BCACP, CPP, FASHP, Regional Associate Dean and Clinical Associate Professor, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, Asheville Campus, and Clinical Associate Professor, UNC School of Medicine Division of Family Medicine, Asheville, NC

Address correspondence to: Dr. Dodd (mdodd@salud.unm.edu).

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacy workforce challenges include oversupply of pharmacy graduates, federal provider status recognition, and variable requirements for education and credentialing of pharmacy technicians, while opportunities for advancing practice include expanding state-level provider recognition, improving reimbursement for clinical services, and increasing the number of states with advanced practice pharmacist licenses.

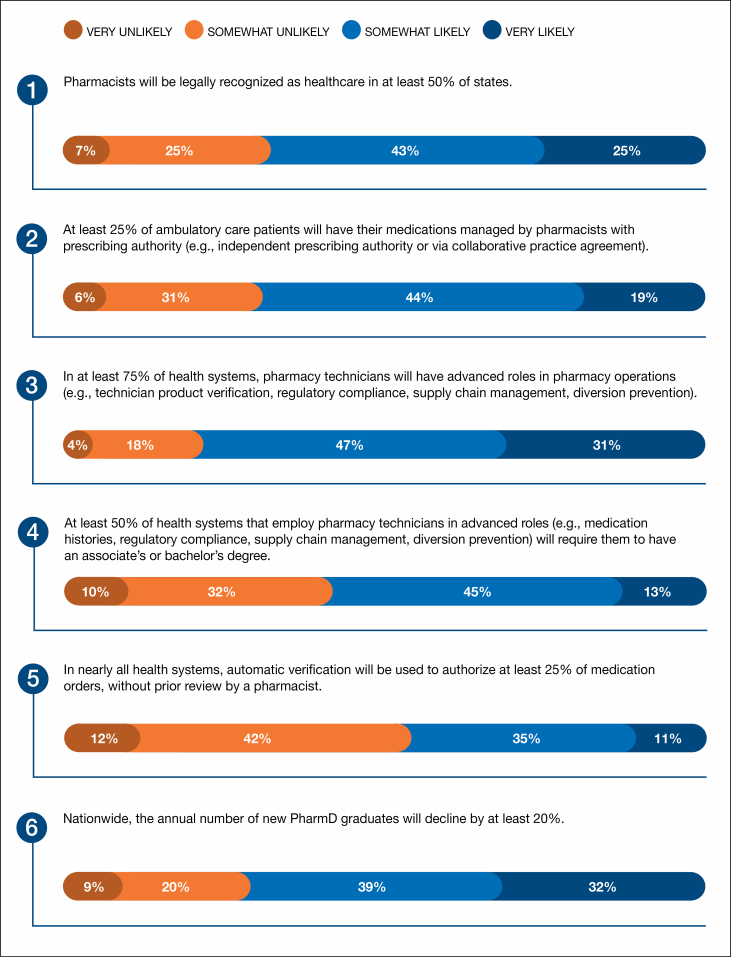

PROVIDER STATUS AND PHARMACIST PRESCRIBING AUTHORITY