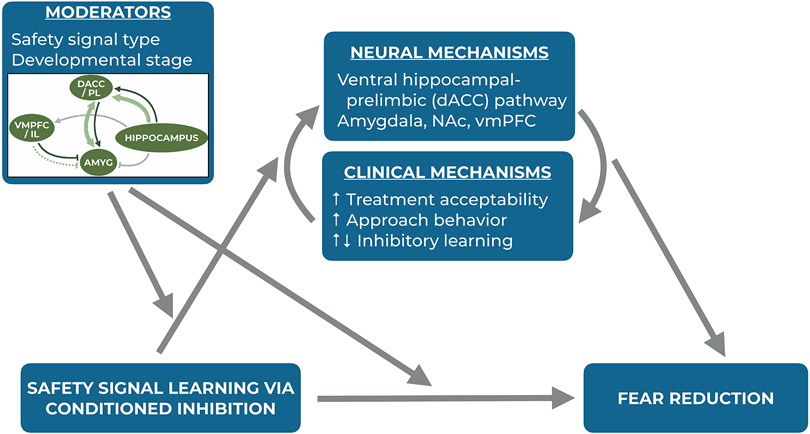

Figure 1. Conceptual model of key mechanisms and moderators related to the effects of safety signal learning via conditioned inhibition.

Safety signal learning via conditioned inhibition may be associated with fear reduction through related neural and clinical mechanisms, and this association may in turn be moderated by factors such as safety signal type and patient’s age. Safety signal learning, the process whereby a stimulus that is trained to signal the absence of threat (i.e., the safety cue) reduces fear in the presence of a threatening cue, is a special class of conditioned inhibition. This process is tested using the summation and retardation tests and differs from fear extinction (see Table 2). Recent cross-species findings highlight the involvement of the ventral hippocampal-PL (dACC in humans) pathway in safety signal learning (107), and previous literature highlights the potential involvement of regions including the amygdala, nucleus accumbens (NAc), and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC; 97,116,122). Safety cues may affect fear during exposure therapy by enhancing treatment acceptability, facilitating approach behavior, and either augmenting or interfering with inhibitory learning (for reviews, see 24,143,163). These neural and clinical processes may interact to enhance or interfere with fear reduction. Safety signal type (i.e., preventative versus restorative safety cues) (for a review, see 163) and developmental stage (i.e., adolescence versus adulthood) may serve as key moderators of the relationship between safety signal learning and fear reduction either directly or through the clinical and/or neural processes. Given marked changes in frontolimbic circuitry from adolescence to adulthood, the neural mechanisms supporting safety signal learning are likely to differ (moderators panel; enlarged in Figure 2) in ways that could lead to differential outcomes in fear reduction depending on developmental stage. In bridging between clinical and neurobiological concepts, this model highlights the importance of future research testing these relationships in basic science and treatment studies.