Abstract

Background:

Shellfish allergy (SA) is one of the most common food allergies causing anaphylaxis in adults and children. There is limited data showing the prevalence of SA in US children.

Objective:

To determine the prevalence and reaction characteristics of SA in the US pediatric population.

Methods:

A cross-sectional food allergy prevalence survey was administered via phone and web by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago from 2015–2016. Point prevalence SA estimates, complex survey weighted proportions and 95% confidence intervals were determined. Relative proportions of demographic characteristics were compared using weighted Pearson chi-square statistics.

Results:

The prevalence of SA was 1.3% (95% CI 1.1–1.5) with more children allergic to crustacean (1.2%; 95% CI 1.0–1.3) than mollusk (0.5%; 95% CI 0.4–0.6). Mean ages of shellfish, crustacean, and mollusk allergy diagnosis were 5.0 (95% CI, 4.4–5.6), 5.1 (95% CI, 4.6–5.6), and 7.7 years old (95% CI, 5.7–9.7), respectively. More than half (54.9%; 95% CI 48.1–61.4) of SA pediatric patients had >1 lifetime food allergy related emergency room visit but only 45.7% (95% CI 39.2–52.4) carried an epinephrine auto-injector. Children with shellfish allergy were more likely to be Black/Hispanic/Latino, and have comorbid asthma, allergic rhinitis or a parental history of asthma, environmental or other food allergies (p<0.001).

Conclusion:

The epidemiology of SA in the US pediatric population shows crustacean allergy is more common than mollusk allergy. A disparity in SA children and epinephrine auto-injector carriage exists. Results from this study will lead to increased awareness of the need for detailed histories, specific diagnostic tests, and rescue epinephrine for anaphylaxis in US children with SA.

Keywords: Shellfish allergy, mollusk allergy, crustacean allergy, prevalence, children, epinephrine

Introduction

Shellfish allergy (SA) is one of the most common food allergies in the world.1 In the United States (US), it is the most common food allergy among adults2 and third most common among children.3 It is one of the top causes of severe reactions3–5 with some studies showing it as the leading cause of anaphylaxis in food allergy.6,7 Within the last two decades, there have been modest advancements in understanding the immunologic mechanisms that contribute to the pathophysiology of SA such as the discovery of tropomyosin, a shellfish allergen which causes cross-reactivity between the two main categories of SA, crustacean and mollusks.8–12 However, there is a substantial gap in literature evaluating the prevalence and characteristics of shellfish allergy among children in the United States.

The two main categories of SA, crustacean (shrimp, crab, lobster, etc.) and mollusk (clam, oyster, mussel, scallop, etc.), have some immunological cross-reactivity13,14 and there is a paucity of data evaluating the epidemiology of these two groups separately, especially in children. A recent meta-analysis examining SA globally found difficulty in comparing results due to the high level of heterogeneity among the studies and too few studies examining prevalence.15 The present study bridges this gap in the literature and not only estimates the prevalence, characteristics, and severity of SA but compares the differences between crustacean allergy and mollusk allergy by leveraging a sample of over 38,000 US children, using a comprehensive sampling approach and a strict diagnostic algorithm to confirm self-reported SA prevalence.

Methods

As detailed in Gupta et al (2018)16 a population-based survey was administered to a nationally-representative sample of US households by NORC at the University of Chicago, an objective non-partisan research institution that delivers reliable data and rigorous analysis to guide critical programmatic, business, and policy decisions, between October 2015 and September 2016, resulting in parent-proxy responses for 38,408 children. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and study activities were approved by the NORC and Northwestern University Institutional Review Boards.

Survey Development and Design

The survey utilized for this study was an updated, expanded version of a previous survey administered in 2009–2010 to determine the US population-level prevalence and severity of childhood food allergy.3 While the core constructs from the 2009–2010 survey were retained, additional questions were added to the instrument to assess emerging research issues relating to the etiology and management of food allergy among US children, including a variety of specific SA. (See Online Repository Appendix A) The final 2015–2016 survey was administered via web or phone and incorporated skip-logic to minimize participant burden. All write-in responses were hand-coded and reviewed by an expert panel of pediatricians, pediatric allergists, and survey methodologists to ensure accuracy of final data.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures for the present study were the prevalence and characteristics of SA in the US pediatric population. A stringent symptom list was developed by the expert panel and used for defining food allergies including SA as well as classifying allergy severity, via a food allergy categorization (Figure 1A and B) used in previous work2. Specifically, SA was defined as having at least one stringent symptom upon ingestion of the responsible allergen, patient report of physician diagnosed SA was used as physician-diagnosed SA and for each SA, the definition of a severe reaction required at least one stringent symptom across two or more different organ systems (i.e., skin/oral mucosa, gastrointestinal (GI), respiratory, cardiovascular). If multiple allergies were reported, each allergy was evaluated separately to determine the accuracy and severity of reaction to the reported allergen. For example, if a patient reported both shrimp and clam allergy, reported reaction symptoms to each allergen would be evaluated separately. Moreover, for the presented analyses that systematically compared characteristics of crustacean-allergic children vs mollusk-allergic children, individuals reporting both allergies were excluded.

Figure 1.

A. Food Allergy Categorization Flow Diagram

B. List of allergic reaction symptoms highlighting stringent symptoms indicative of convincing shellfish allergy.

Coastal residence was determined at the county level using the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) definitions of coastal state, coastal watershed county (counties where land use and water quality changes most directly impact coastal ecosystems), and coastal shoreline county (counties that are directly adjacent to the open ocean, major estuaries, and the Great Lakes)—excluding counties bordering the Great Lakes coastline.17 SA children were also described based on their residence in the region of the U.S. defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. (See Supplemental Figure E1.)

Four regions were assessed (Northeast, Midwest, South and West) and these were further subdivided into 9 divisions (1: New England, 2: Middle Atlantic, 3: East North Central, 4: West North Central, 5: South Atlantic, 6: East South Central, 7: West South Central, 8: Mountain, 9: Pacific).

Study Participants, Survey Weighting, and Statistical Analysis

Both parents (≥18 years old) and children (< 18 years old) residing in a US household who could complete a survey in English or Spanish either online or via telephone were eligible to participate in the present study. This study relied upon a nationally-representative household panel to support population-level inference.3 Study participants were first recruited from NORC at the University of Chicago’s nationally-representative probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, where a survey completion rate of 51.2% was observed. AmeriSpeak is a probability-based panel, with households selected from a documented randomly selected list of households in the US are sampled by address, and then contacted by U.S. mail and by NORC telephone and field interviewers. It provides at least 97 percent sample coverage of the U.S. population by supplementing the U.S. Postal Service Delivery Sequence File. To increase precision, these population-weighted AmeriSpeak responses were augmented by calibration-weighted, non-probability-based responses obtained through Survey Sampling International. The final, combined sample weight was derived by applying an optimal composition factor that minimizes mean square error associated with food allergy prevalence estimates.18,19 See Gupta et al. for additional detail regarding the sampling, weighting, and analysis procedures utilized.2

Complex survey weighted proportions and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the “svy”: family of commands in STATA 14, while relative proportions of demographic characteristics were compared using weighted Pearson chi-square statistics, which are corrected for the complex survey design. Covariate-adjusted complex survey weighted logistic regression models compared relative prevalence and other assessed SA outcomes by participant characteristics. Two-sided hypothesis tests were utilized, with p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Surveys were completed for 38,408 children. Ninety-two percent (92.4%) of participants (n= 35,489) of the total 38,408 participants had no convincing history of food allergy. Seven (7.6%) had a history of convincing allergy. Of those, 599 children were found to have convincing SA, with 322 children with only crustacean allergy, 50 children with only mollusk allergy, and 227 children with both crustacean and mollusk allergy. Prevalence of shellfish allergy by allergen types and age categories is presented in Table 1. Overall, the prevalence of SA was 1.3% (95% CI 1.1 – 1.5) with more children allergic to crustacean than mollusk at a prevalence of 1.2% (95% CI 1.0 – 1.3) and 0.5% (95% CI 0.4 – 0.6) respectively. The greatest prevalence of crustacean allergy appeared in children 6 – 17 years old, while the prevalence of mollusk allergy did not increase until children were 14 – 17 years of age [0.8%; 95% CI (0.5 – 1.3)]. The prevalence of children with crustacean allergy only (no mollusk) [0.6%; 95% CI (0.5 – 0.8)] was greater than the prevalence of children with both crustacean and mollusk allergy [0.5%; CI (0.4 – 0.6)].

Table 1.

Prevalence Estimates of Shellfish, Crustacean and Mollusk Allergy Among US Children.

| Age Groups | % (95%CI) of US Children with Convincing Shellfish Allergy | % (95%CI) of US Children with both Crustacean and Mollusk Allergy | % (95%CI) of US Children with Any Convincing Crustacean Allergy | % (95%CI) of US Children with Any Convincing Mollusk Allergy | % (95%CI) of US Children with Convincing Crustacean Allergy Only (no mollusk allergy) | % (95%CI) of US Children with Convincing Mollusk Allergy Only (no crustacean allergy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convincing shellfish allergy prevalence among all children | ||||||

| All ages | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | .5 (.4–.6) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | .6 (.5–.8) | .6 (.5–.8) | .12 (.06–.23) |

| 0–2 Years | .6 (.4–1.0) | .2 (.1–.6) | .5 (.3–.8) | .3 (.2–.6) | .2 (.1–.4) | .07 (.03–.18) |

| 3–5 Years | 1.1 (.7–1.7) | .6 (.3–1.1) | 1.1 (.7–1.7) | .6 (.3–1.2) | .5 (.3–.9) | .02 (.004–.09) |

| 6–10 Years | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | .6 (.4–.9) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | .7 (.5–1.0) | .8 (.6–1.1) | .08 (.04–.15) |

| 11–13 Years | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | .5 (.3–.8) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | .6 (.5–.9) | .9 (.7–1.2) | .13(.07–.26) |

| 14–17 Years | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | .6 (.4–.8) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | .8 (.5–1.3) | .7 (.5–.9) | .27 (.09–.87) |

| Physician-diagnosed convincing shellfish allergy prevalence among all children | ||||||

| All ages | .8 (.6–.9) | .2 (.2–.3) | .7 (.6–.8) | .3 (.2–.4) | .4 (.4–.5) | .11 (.05–.23) |

| 0–2 Years | .3 (.1–.6) | .05 (.02–.12) | .2 (.1–.3) | .2 (.1–.5) | .1 (.1–.2) | .14 (.03–.57) |

| 3–5 Years | .5 (.4–.7) | .2 (.1–.4) | .5 (.4–.7) | .2 (.1–.4) | .3 (.2–.5) | .01 (.002–.10) |

| 6–10 Years | .8 (.6–1.1) | .2 (.1–.3) | .7 (.5–1.0) | .2 (.2–.4) | .5 (.3–.8) | .05 (.02–.11) |

| 11–13 Years | 1.1 (.8–1.4) | .4 (.2–.6) | 1.0 (.7–1.3) | .5 (.3–.7) | .6 (.4–.9) | .10 (.05–.22) |

| 14–17 Years | 1.0 (.7–1.5) | .2 (.2–.4) | .8 (.6–1.0) | .5 (.2–1.0) | .5 (.4–.7) | .22 (.05–.91) |

Estimated demographic characteristics, medical history, and family history of atopic diseases of this US population-weighted study population are presented in Table 2. The mean ages of shellfish, crustacean, and mollusk allergy diagnosis were 5.0 (95% CI, 4.4 – 5.6), 5.1 (95% CI, 4.6 – 5.6), and 7.7 years old (95% CI, 5.7 – 9.7) respectively. When combining the age of diagnosis with our adult cohort, the mean age for shellfish was 15.9 years with the average age for crustacean and mollusk allergy being 16.8 and 19.4 years, respectively. The age distribution of SA children showed higher prevalence rates among children greater than 6 years old. (p=0.01) Compared to the general US pediatric population, children with shellfish allergy were more likely to be Black or Hispanic/Latino, and more likely to have comorbid asthma, allergic rhinitis, as well as a family history of asthma, environmental allergies, or other food allergies (p<0.001). Age distribution between exclusively crustacean-allergic and exclusively mollusk-allergic children in the US where half of exclusively mollusk-allergic were 14–17 years of age, compared to only 25% of exclusively crustacean-allergic trended towards significance (p=0.05). Conversely, more than one-third of exclusively crustacean-allergic children were age 6–10 years compared to only 18.4% of exclusively mollusk-allergic. No significant differences in crustacean or mollusk allergy prevalence were observed between male and female respondents.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population % (95% CI)

| Variable | All Children | Children with Convincing Shellfish Allergy | p-value | Children with Convincing Crustacean Allergy Only (no mollusk allergy) | Children with Convincing Mollusk Allergy Only (no crustacean allergy) | p- value comparing mollusk vs crustacean allergic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||||

| 0–2 Years | 16.1 (15.2–16.9) | 7.6 (4.9–11.7) | 0.01 | 6.0 (3.7–9.5) | 9.1 (3.0–24.3) | 0.05 |

| 3–5 Years | 16.2 (15.5–17.0) | 13.6 (8.9–20.3) | 12.6 (7.3–20.9) | 2.6 (.5–12.2) | ||

| 6–10 Years | 27.9 (26.9–28.8) | 31.7 (25.7–38.4) | 34.2 (26.5–42.8) | 18.4 (7.8–37.7) | ||

| 11–13 Years | 16.6 (15.9–17.4) | 19.7 (15.7–24.4) | 22.9 (17.4–29.6) | 17.9 (7.2–38.0) | ||

| 14–17 Years | 23.4 (22.4–24.4) | 27.3 (21.5–34.0) | 24.3 (18.7–31.0) | 52.1 (24.0–78.9) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 48.9 (47.8–50.0) | 46.5 (39.9–53.2) | 0.48 | 48.2 (40.2–56.2) | 39.4 (17.7–66.4) | 0.54 |

| Male | 51.1 (50.0–52.2) | 53.5 (46.8–60.1) | 51.8 (43.8–59.8) | 60.6 (33.6–82.3) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian, Non-Hispanic | 3.2 (2.8–3.7) | 4.3 (2.8–6.7) | <.001 | 5.0 (3.0–8.3) | 4.2 (.9–17.3) | 0.11 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 13.2 (12.3–14.2) | 22.9 (17.6–29.1) | 23.1 (16.5–31.4) | 9.5 (3.2–25.0) | ||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 52.8 (51.2–54.4) | 39.9 (33.5–46.7) | 45.0 (37.0–53.1) | 69.4 (44.8–86.4) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 24.1 (22.5–25.7) | 27.3 (21.2–34.4) | 21.3 (15.2–28.9) | 15.8 (6.2–34.8) | ||

| Multiple/Other | 6.6 (6.1–7.3) | 5.7 (4.0–8.0) | 5.6 (3.6–8.7) | 1.1 (.1–7.8) | ||

| Country of Birth | ||||||

| Born in US | 97.8 (97.4–98.1) | 97.5 (93.2–99.1) | 0.81 | 98.2 (94.7–99.4) | 100 | 0.47 |

| Born outside US | 2.2 (1.9–2.6) | 2.5 (.9–6.8) | 1.8 (.6–5.3) | 0 | ||

| Household income | ||||||

| <25K | 16.1 (14.9–17.3) | 16.2 (10.9–23.3) | 0.56 | 12.8 (8.3–19.1) | 6.1 (1.6–20.6) | 0.16 |

| 25K-49K | 22.2 (20.9–23.5) | 19.6 (14.9–25.2) | 21.8 (15.1–30.3) | 23.7 (9.9–46.8) | ||

| 50K-99K | 31.1 (29.8–32.5) | 34.2 (28.7–40.2) | 33.1 (26.6–40.3) | 31.6 (14.4–56.0) | ||

| 100K-149K | 19.2 (18.0–20.5) | 16.3 (12.5–20.9) | 18.1 (13.0–24.5) | 2.9 (.7–10.3) | ||

| 150K+ | 11.4 (10.3–12.6) | 13.8 (8.6–21.5) | 14.3 (8.4–23.3) | 35.8 (9.2–75.3) | ||

| Census Region | ||||||

| West | 24.5 (23.0–26.0) | 22.4 (17.0–28.9) | 0.04 | 24.5 (19.0–30.9) | 45.0 (16.9–76.7) | 0.14 |

| Midwest | 20.7 (19.6–21.9) | 16.0 (12.1–20.8) | 12.5 (8.6–17.9) | 18.9 (7.7–39.5) | ||

| South | 38.6 (37.1–40.2) | 38.8 (32.6–45.5) | 37.8 (30.1–46.1) | 28.1 (12.4–51.9) | ||

| Northeast | 16.2 (15.1–17.3) | 22.8 (17.1–29.7) | 25.3 (18.1–34.2) | 8.0 (2.9–20.0) | ||

| Census Division | ||||||

| New England | 3.9 (3.4–4.5) | 4.3 (2.0–8.9) | 0.17 | 5.1 (1.7–14.0) | 1.6 (.3–7.8) | 0.005 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 12.4 (11.4–13.5) | 18.6 (13.4–25.3) | 20.5 (14.2–28.7) | 6.4 (2.1–17.7) | ||

| East North Central | 12.5 (11.6–13.5) | 9.9 (7.2–13.4) | 8.2 (5.0–13.0) | 13.1 (4.6–31.9) | ||

| West North Central | 8.9 (8.2–9.7) | 6.3 (3.8–10.4) | 4.5 (2.4–8.1) | 5.9 (1.8–17.3) | ||

| South Atlantic | 19.6 (18.4–20.8) | 22.4 (17.3–28.4) | 23.2 (16.6–31.4) | 14.8 (5.9–32.4) | ||

| East South Central | 5.7 (5.0–6.5) | 3.8 (2.3–6.2) | 4.2 (2.2–7.9) | 7.9 (2.1–25.0) | ||

| West South Central | 13.7 (12.5–14.9) | 12.9 (9.1–18.1) | 10.9 (6.8–16.9) | 5.4 (1.5–17.3) | ||

| Mountain | 7.7 (7.0–8.6) | 8.4 (4.2–16.0) | 6.8 (4.2–10.9) | 36.4 (9.7–75.4) | ||

| Pacific | 15.6 (14.3–17.0) | 13.4 (10.4–17.1) | 16.7 (12.3–22.4) | 8.6 (2.9–22.8) | ||

| Residential Proximity to the coast | ||||||

| Coastal States | 60.0 (58.5–61.4) | 65.0 (58.0–71.4) | 0.15 | 66.7 (58.4–74.0) | 33.0 (15.0–57.9) | 0.008 |

| Inland States | 40.0 (38.6–41.5) | 35.0 (28.6–42.0) | 33.3 (26.0–41.6) | 67.0 (42.1–85.0) | ||

| Coastal Watershed Counties | 50.3 (48.7–51.9) | 54.0 (47.1–60.8) | 0.29 | 56.9 (48.7–64.6) | 30.3 (13.6–54.7) | 0.04 |

| Non-Coastal Watershed Counties | 49.7 (48.1–51.3) | 46.0 (39.2–52.9) | 43.1 (35.4–51.3) | 69.7 (45.3–86.5) | ||

| Shoreline Counties | 36.9 (35.3–38.4) | 44.1 (37.6–50.9) | 0.03 | 48.1 (40.0–56.3) | 25.6 (11.2–48.3) | 0.06 |

| Non-Shoreline Counties | 63.2 (61.6–64.7) | 55.9 (49.1–62.4) | 51.9 (43.7–60.0) | 74.4 (51.7–88.8) | ||

| Age of SA diagnosis (Mean, 95%CI) | 5.0 (4.4–5.6) | 5.1 (4.6–5.6) | 7.7 (5.7–9.7) | |||

| Physician diagnosed comorbidities | ||||||

| Asthma | 12.2 (11.4–13.0) | 41.7 (34.7–48.9) | <.001 | 37.4 (29.8–45.6) | 44.2 (16.2–76.5) | 0.7 |

| Eczema | 5.9 (5.3–6.5) | 14.7 (10.2–20.6) | <.001 | 11.9 (6.6–20.4) | 11.2 (3.5–30.6) | 0.92 |

| Allergic Rhinitis | 12.8 (12.0–13.6) | 33.0 (27.5–39.2) | <.001 | 29.3 (23.1–36.3) | 25.3 (11.0–48.2) | 0.71 |

| Insect sting allergy | 2.2 (1.9–2.6) | 12.3 (8.3–17.9) | <.001 | 12.1 (6.9–20.5) | 13.7 (5.1–32.2) | 0.82 |

| Latex allergy | 1.0 (.8–1.3) | 7.4 (5.3–10.2) | <.001 | 9.1 (5.9–13.7) | 3.4 (.9–12.1) | 0.14 |

| Medication allergy | 4.2 (3.7–4.7) | 11.7 (8.4–16.0) | <.001 | 12.3 (8.1–18.3) | 16.4 (6.2–36.9) | 0.58 |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | .16 (.12-.22) | .57 (.23–1.40) | 0.005 | .85 (.31–2.34) | 0 | 0.45 |

| Family history of allergic diseases | ||||||

| Parental asthma | 18.3 (17.2–19.5) | 43.4 (36.6–50.4) | <.001 | 43.1 (35.0–51.6) | 22.4 (9.9–43.0) | 0.06 |

| Parental eczema | 15.6 (14.5–16.7) | 29.3 (23.2–36.3) | <.001 | 23.8 (18.3–30.3) | 17.4 (6.6–38.3) | 0.49 |

| Parental environmental allergies | 40.1 (38.6–41.6) | 62.6 (55.6–69.2) | <.001 | 60.3 (52.1–67.9) | 38.2 (17.2–64.9) | 0.12 |

| Parental FA | 19.4 (18.3–20.5) | 59.8 (52.8–66.5) | <.001 | 64.8 (56.5–72.4) | 35.4 (16.1–61.1) | 0.03 |

Children exclusively allergic to crustaceans (i.e. not mollusk-allergic) were more likely to reside in the New England, Mid-Atlantic, South Atlantic, and Pacific divisions, relative to their non-shellfish-allergic peers and children who were exclusively mollusk-allergic were more likely to reside in East North Central, East South Central, and Mountain divisions compared to their non-shellfish-allergic peers (p<0.01). Those with both mollusk and crustacean allergy were more likely to reside in the Mid-Atlantic, South Atlantic, and West South Central divisions. Overall, children with SA were more likely to reside in a shoreline county.

The distribution of symptom characteristics, allergy severity and outcomes among children with shellfish allergy is shown on Table 3. In order of frequency reported, the most common systems involved in shellfish-allergic reactions were skin/oral/mucosal, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular. Reported symptom prevalence was similar between children with mollusk allergy and crustacean allergy in all systems except for skin/oral/mucosal tissue and cardiovascular system. Among children with crustacean allergy, 70.2% (95% CI 62.4–77.0) experienced itching compared to 32.4% (95% CI 14.6 – 57.3) in those with mollusk allergy. Children with crustacean allergy also were more likely to report chest pain than those who were mollusk-allergic [7.9%; 95% CI (4.4 – 13.9) vs. 1.5% 95% CI (0.3 – 6.7); P = 0.02]. The frequency of reported gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms were not different between the two groups.

Table 3.

Symptom Characteristics and Outcomes of Children with Shellfish Allergy, % (95% CI) with stringent symptoms in italics

| Symptoms | All Shellfish | Children with Convincing Crustacean Allergy Only | Children with Convincing Mollusk Allergy Only | P value comparing symptoms between Crustacean vs Mollusk allergic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin/Oral/Mucosal Tissue | ||||

| Any Skin/Oral/Mucosal Tissue Symptom(s) to Shellfish | 96.4 (93.8–97.9) | 96.9 (93.6–98.6) | 97.6 (91.1–99.4) | 0.76 |

| Any Stringent Skin/Oral/Mucosal Symptom(s) to Shellfish | 85.3 (80.8–88.9) | 88.0 (81.1–92.7) | 93.5 (80.7–98.0) | 0.26 |

| Hives | 75.3 (68.9–80.8) | 71.6 (64.1–78.1) | 83.6 (66.0–93.0) | 0.17 |

| Itching | 70.9 (64.1–77.0) | 70.2 (62.4–77.0) | 32.4 (14.6–57.3) | 0.002 |

| Rash | 64.7 (58.8–70.2) | 58.5 (50.6–65.9) | 66.1 (40.6–84.8) | 0.56 |

| Swelling | 35.7 (29.3–42.7) | 29.1 (22.3–37.1) | 14.7 (6.0–31.6) | 0.1 |

| Lip/tongue swelling | 34.4 (28.2–41.2) | 29.3 (22.5–54.4) | 19.4 (8.2–39.2) | 0.31 |

| Difficulty swallowing | 31.2 (25.3–37.8) | 25.2 (19.5–31.9) | 23.1 (9.9–45.2) | 0.83 |

| Hoarse voice | 12.6 (9.6–16.5) | 11.8 (8.4–16.2) | 12.1 (4.4–29.4) | 0.96 |

| Itchy mouth | 34.1 (27.8–40.9) | 31.3 (24.4–39.2) | 23.3 (10.0–45.4) | 0.45 |

| Throat tightening | 30.2 (23.5–37.9) | 19.9 (14.9–26.0) | 48.7 (20.6–77.7) | 0.04 |

| Mouth or throat tingling | 14.3 (10.3–19.6) | 3.7 (1.1–11.6) | 0.02 | |

| Respiratory | ||||

| Any Respiratory Symptom(s) to Shellfish | 48.0 (40.0–56.1) | 55.0 (27.3–79.9) | 0.37 | |

| Any Stringent Respiratory Symptom(s) to Shellfish | 44.1 (37.3–51.2) | 37.0 (29.9–44.8) | 46.8 (18.7–77.2) | 0.57 |

| Chest tightening | 19.3 (13.6–26.6) | 15.4 (10.9–21.3) | 32.8 (7.2–75.5) | 0.29 |

| Nasal congestion | 14.6 (10.7–19.5) | 12.1 (7.8–18.2) | 6.0 (1.9–17.9) | 0.25 |

| Repetitive cough | 15.9 (11.2–22.2) | 10.5 (7.2–15.0) | 12.8 (4.7–30.4) | 0.71 |

| Trouble breathing | 27.0 (20.5–34.7) | 17.1 (12.9–22.4) | 37.5 (10.5–75.4) | 0.2 |

| Wheezing | 22.8 (16.9–30.0) | 16.4 (11.2–23.3) | 40.6 (13.0–75.8) | 0.11 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Any Gastrointestinal Symptom(s) to Shellfish | 42.0 (35.4–48.8) | 34.2 (27.3–41.8) | 23.7 (10.6–44.9) | 0.46 |

| Any Stringent Gastrointestinal Symptom(s) to Shellfish | 17.9 (13.4–23.5) | 10.9 (7.5–15.7) | 7.5 (2.7–18.9) | 0.47 |

| Belly pain | 19.1 (14.0–25.5) | 10.1 (6.6–15.1) | 13.0 (5.3–28.8) | 0.6 |

| Cramps | 13.9 (9.3–20.2) | 6.1 (3.8–9.7) | 11.3 (4.3–26.7) | 0.26 |

| Diarrhea | 19.0 (13.5–26.0) | 12.8 (8.5–19.0) | 10.7 (3.9–26.1) | 0.73 |

| Nausea | 19.0 (14.8–24.1) | 14.3 (10.2–19.8) | 7.5 (2.6–19.7) | 0.22 |

| Vomiting | 10.9 (7.5–15.7) | 7.5 (2.7–18.9) | 0.47 | |

| Cardiovascular | ||||

| Any Cardiovascular Symptom(s) to Shellfish | 23.9 (18.0–31.0) | 8.4 (3.3–19.8) | 0.02 | |

| Any Stringent Cardiovascular Symptom(s) to Shellfish | 26.9 (21.1–33.7) | 22.4 (16.8–29.2) | 8.4 (3.3–19.8) | 0.03 |

| Chest pain | 10.1 (6.9–16.8) | 7.9 (4.4–13.9) | 1.5 (.3–6.7) | 0.02 |

| Rapid heart rate | 15.5 (10.7–22.0) | 8.0 (5.1–12.3) | 3.0 (.7–11.7) | 0.17 |

| Fainting, dizziness, or feeling light headed | 12.1 (8.4–17.1) | 8.3 (5.5–12.3) | 3.5 (1.2–10.1) | 0.13 |

| Low blood pressure | 4.2 (2.5–7.0) | 4.1 (2.1–8.1) | 1.4 (.2–10.3) | 0.31 |

| Shellfish Allergy Outcomes | ||||

| Multiple Food Allergies (including individual shellfish allergies) | 74.0 (68.0–79.2) | 55.7 (47.3–63.7) | 58.1 (30.8–81.2) | 0.9 |

| Multiple Food Allergies (besides shellfish allergies) | 37.6 (31.1–44.4) | 26.3 (20.6–32.8) | 13.6 (5.3–30.8) | 0.13 |

| Only Mild to moderate reactions to Shellfish | 51.3 (44.5–58.1) | 56.0 (48.1–63.6) | 52.4 (22.6–80.5) | 0.83 |

| 1+ Severe reactions to Shellfish | 48.7 (41.9–55.5) | 44.0 (36.4–51.9) | 47.6 (19.5–77.4) | |

| 1+ Lifetime FA-related ED Visit | 54.9 (48.1–61.4) | 46.9 (39.0–54.9) | 61.6 (35.0–82.7) | 0.3 |

| 1+ Last Year FA-related ED Visits | 22.7 (17.1–29.4) | 18.7 (14.0–24.6) | 9.0 (2.8–25.0) | 0.18 |

| Has Current Epinephrine Auto-Injector Prescription | 45.7 (39.2–52.4) | 50.7 (42.7–58.8) | 34.7 (15.5–60.6) | 0.24 |

| Has been treated with EAI for shellfish-allergic reaction | 37.8 (31.1–45.0) | 35.5 (28.1–43.7) | 55.2 (27.6–80.0) | 0.19 |

| Has been treated with Albuterol for shellfish-allergic reaction | 24.7 (18.2–32.7) | 19.1 (13.7–26.0) | 36.4 (9.7–75.3) | 0.3 |

Over half of shellfish allergic pediatric patients had more than one lifetime food allergy-related emergency room (ED) visit and almost one fourth visited the ED in the previous year for any type of food-allergy related reaction. This is shown in Table 3 as the percentage of survey respondents who answered yes to visiting to the ED due to their shellfish allergy (54.9%) and having ED visits within the last year (22.7%). Fewer than half of shellfish-allergic patients carried a current epinephrine auto-injector but more than one-third had been treated with an epinephrine auto-injector for a shellfish allergic reaction in their lifetime. There were no significant differences seen in the frequency of reactions characterized as severe, nor were there significant differences in health care utilization between crustacean and mollusk allergic children.

Table 4 shows the adjusted associations between a variety of demographic/comorbid atopic disease characteristics and key shellfish allergy outcomes. Children living in a shoreline county residence were significantly associated with having only crustacean allergy (OR: 1.4, 95% CI 1.1 – 1.9). Children reporting Black, Non-Hispanic race/ethnicity were more likely to have shellfish allergy (OR: 2.3, 95% CI 1.6 – 3.4) and crustacean allergy (OR: 2.6, 95% CI 1.8 – 3.8) compared to their White counterparts. Additionally, the odds of having only mollusk allergy were increased among Black (OR: 2.6, 95% CI 1.5 – 4.6) and Hispanic (OR: 1.9, 95% CI 1.1 – 3.1) children, relative to White children. Children 6 – 10 years and 14 – 17 years of age had increased odds of having crustacean allergy (OR: 2.1, 95% CI 1.2 – 3.6;OR: 1.8, 95% CI 1.1 – 3.1, respectively). Children with comorbid insect sting or latex allergies had greater odds of crustacean allergy, which may be a potential indicator of atopic predisposition.

Table 4.

Adjusted Associations for Demographics, Comorbid Diseases, and Severity of the Diagnosis Among Children with Shellfish Allergy and Shellfish Allergy Subgroups.

| Variable | Odds of Convincing Shellfish Allergy Among All Children (95% CI) | Odds of Convincing Crustacean Allergy (with or without mollusk) Among All Children (95% CI) | Odds of Convincing Mollusk Allergy (with or without Crustacean Allergy) Among All Children (95% CI) | Odds of Severe Shellfish Reactions Among Children with Convincing Shellfish Allergy (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoreline County | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 1.1 (.7–1.8) | 1.1 (.6–1.8) |

| Race/ethnicity (vs. White, non-Hispanic) | ||||

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 1.7 (.9–3.1) | 1.8 (1.0–3.3) | 1.5 (.5–4.3) | .6 (.2–1.8) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2.3 (1.6–3.4) | 2.6 (1.8–3.8) | 2.6 (1.5–4.6) | 1.4 (.7–2.8) |

| Hispanic | 1.4 (.9–2.0) | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 1.9 (1.1–3.1) | .6 (.3–1.1) |

| Multiple/other | .9 (.6–1.5) | 1.1 (.7–1.8) | 1.1 (.6–2.1) | 1.5 (.6–3.6) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female vs. Male | .9 (.7–1.2) | 1.0 (.7–1.3) | .9 (.6–1.4) | 1.0 (.6–1.6) |

| Country of Birth | ||||

| Born in US | .9 (.3–2.5) | .8 (.3–2.3) | .7 (.2–2.7) | .4 (.1–3.1) |

| Age (vs. <3 years) | ||||

| 3–5 Years | 1.5 (.8–2.9) | 1.9 (1.0–3.9) | 1.6 (.6–4.3) | 1.9 (.6–6.1) |

| 6–10 Years | 1.7 (1.0–2.8) | 2.1 (1.2–3.6) | 1.5 (.7–3.2) | .8 (.3–2.1) |

| 11–13 Years | 1.5 (.9–2.6) | 1.8 (1.0–3.2) | 1.2 (.6–2.6) | 1.3 (.5–3.8) |

| 14–17 Years | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) | 1.8 (1.1–3.1) | 1.9 (.9–4.0) | 1.3 (.5–3.6) |

| Household income, $ (v <$25,000) | ||||

| 25,000–49,999 | .9 (.5–1.6) | .9 (.5–1.6) | .7 (.3–1.7) | .2 (.1-.6) |

| 50,000–99,999 | 1.3 (.8–2.1) | 1.3 (.8–2.1) | 1.2 (.6–2.6) | .6 (.2–1.3) |

| 100,000–149,000 | .9 (.5–1.6) | 1.0 (.6–1.8) | .8 (.3–1.8) | .3 (.1-.7) |

| >150,000 | 1.4 (.7–2.9) | 1.2 (.6–2.3) | 1.3 (.4–4.0) | .4 (.1–1.4) |

| Comorbid Conditions (vs. not) | ||||

| Asthma | 3.5 (2.4–5.2) | 3.5 (2.5–5.0) | 4.3 (2.3–8.0) | 2.2 (1.3–3.7) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1.5 (.9–2.5) | 1.4 (.8–2.5) | 1.7 (.9–3.1) | .7 (.3–1.6) |

| Allergic Rhinitis | 2.0 (1.4–2.9) | 2.1 (1.5–2.9) | 2.3 (1.3–4.0) | 1.3 (.8–2.2) |

| Insect Sting Allergy | 4.7 (2.8–7.8) | 4.2 (2.3–7.4) | 3.6 (1.8–7.2) | .9 (.4–1.9) |

| Latex Allergy | 4.2 (2.3–7.8) | 4.6 (2.5–8.5) | 2.9 (1.3–6.6) | 2.2 (1.0–4.7) |

| Medication Allergy | 1.6 (1.0–2.7) | 1.4 (.8–2.4) | 1.2 (.6–2.4) | 1.0 (.5–1.9) |

| Eosinophilic Esophagitis | .9 (.2–3.9) | .9 (.2–4.3) | .3 (.0–3.0) | .6 (.1–3.3) |

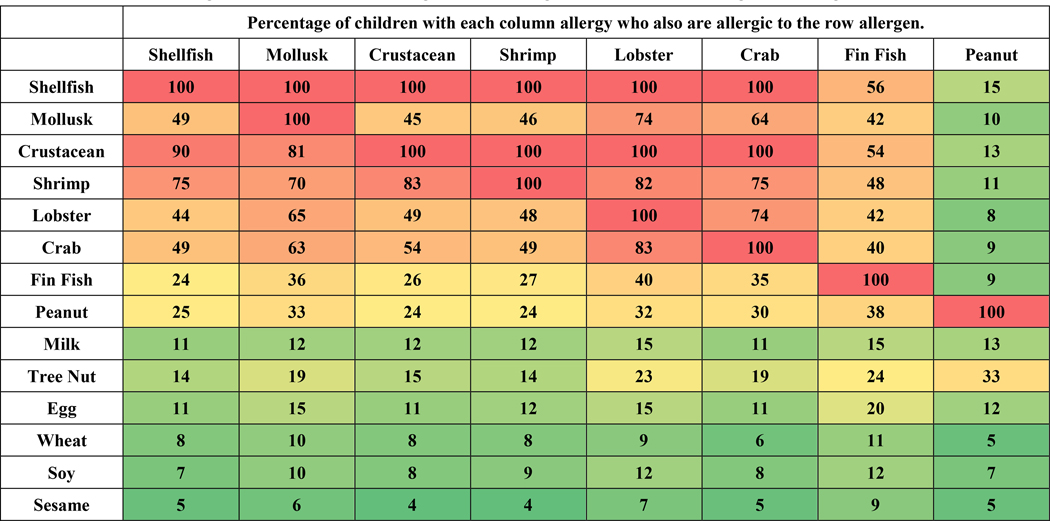

Figure 2 reports rates of comorbidity among and between shellfish allergies and the co-existence of other common food allergies. The highest rates were observed among shrimp, crab and lobster allergies and between crustacean and mollusk allergy. This co-existence of clinical allergic disease may be caused by cross reactivity of pan-allergens like tropomyosin or other unique allergens. Prior studies have reported only 14% of patients with crustacean allergy reporting a mollusk allergy.13 In our study, of the children who were crustacean-allergic, 45% were also allergic to mollusks, however, of the mollusk allergic children, 81% were also allergic to crustaceans. Among children with mollusk allergy, the most common accompanying allergy was shrimp (70%) followed by lobster (65%), crab (63%) and fin fish (36%). Children with mollusk allergy had higher rates of co-existing fin fish (36%) and peanut allergy (33%) than those with crustacean allergy (26% and 24% respectively). A greater percentage of children with fin fish allergy also had comorbid crustacean allergy (54%) compared to mollusk allergy (42%). The percentage of children with peanut allergy who also have crustacean allergy was 13% while those with concurrent mollusk allergy was 10%.

Figure 2.

Comorbidities Among Shellfish Allergies and Other Co-existing Food Allergies. Each cell has the percentage of children with each column allergy who also are allergic to the row allergen

Discussion

This study bridges a large gap in SA literature by defining the prevalence and comparing the characteristics of crustacean and mollusk allergy in a large, representative group of children living in the United States. This is the largest study to date of shellfish allergy and no previous cross-sectional studies of this caliber exist in this population. Our strict criteria for defining shellfish allergy give a more complete prevalence of SA in the US and we also had the unique opportunity to examine demographic information of both the pediatric and adult population. The pediatric prevalence of shellfish allergy in our study was 1.3%, which is substantial and within range of previously reported studies.1

Our findings indicate that the average age of the first reaction to shellfish in SA is younger than previously acknowledged and suggests that SA affects the pediatric population to a significant degree. When examining both children and adults together, the average age of shellfish diagnosis across the US population was 15.9 years with the average age for crustacean and mollusk allergy being 16.8 and 19.4 years, respectively. Previous studies report the average age of diagnosis is in adulthood13 while others analyzed age of onset in children and adults separately.20,21 Another possible explanation for this low age of diagnosis is that shellfish has become gradually more ubiquitous in the US diet22 and more children may be exposed at an earlier age.

It is also important to note the geographic differences between mollusk and crustacean allergic children in the United States. Previous studies of coastal Asian populations have reported high prevalence rates of SA compared to populations living away from the coast, suggesting a possible relationship between increased exposure to shellfish and SA risk.23–25 Based on these studies, the determination of SA risk in the US population could include “proximity to the coast” which may increase the likelihood of shellfish exposure, thus increasing the risk of SA development. There have been no previous studies evaluating this hypothesis.

While our data shows consistency with the “proximity to the coast” hypothesis in children with shellfish allergy and crustacean allergy, this was not the case with mollusk allergy. Children with mollusk only allergy were more likely to reside in inland states or non-costal watershed counties. A possible explanation for this finding may be preparation of mollusks inland (cooked) compared to near the coast (raw). Inland states have less ingestion of raw shellfish, as evidenced by the increased number of seafood associated infections inland.26 Inland seafood ingestion is more likely to be cooked, given the risks of infection. Changes in food allergenicity with cooking have been shown to occur in other foods, such as peanuts, milk, and eggs.27–30 The effect on allergenicity through heating shellfish has been shown to influence IgE binding in squid and scallops.31,32 Additionally, different species of mollusk may result in an increased risk of developing an allergy in specific regions. While in Thailand, SA patients with anaphylaxis to fresh water shrimp may not have the same reaction to saltwater shrimp or vice versa31, this has not been explored for mollusks and our current study did not examine the specific species of shellfish consumed. Further studies are needed to explore the effects of cooking modalities in shellfish allergenicity and species-specific immune responses on SA prevalence.

There is a paucity of data evaluating the epidemiology and prevalence of mollusk allergy among children in the US. Our study is the first study of this size to directly compare presentation of crustacean allergy with mollusk allergy and to define the characteristics of mollusk allergy. We specifically explored the prevalence of crustacean allergy and mollusk allergy, which was 1.2% and 0.6% respectively. This is consistent with a recent meta-analysis that found crustacean allergy to be more prevalent than mollusk allergy globally.15 More than 80% of consumption of seafood in the US in 2017 was comprised of ten fish and shellfish products, with shrimp as the top consumed seafood at 4.4 pounds per person and clam as the tenth at 0.31 pounds per person. (https://www.seafoodhealthfacts.org/seafood-choices/overview-us-seafood-supply, Accessed 9/2/2019)33. The relative difference in exposure by consumption may contribute to the higher prevalence of crustacean vs mollusk allergy in US children.

Previously reported prevalence in 2004 by Sicherer et. al was 0.5%13 and the NHANES survey from 2007–2010 reported a prevalence of 0.87%.32 This trend suggests that pediatric SA may have been increasing since the early 2000s. For comparison, the estimated prevalence of peanut allergy among US children has ranged from 1.2% – 2.2%1,33 suggesting that shellfish allergy should be a public health concern in the pediatric population. In a study using information from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, a database that captures a nationally represented sample of food allergic and anaphylactic events at the emergency department (ED), the most common food for ED visits was shellfish in children 6–18 years old and shellfish was one of the top foods to result in hospitalizations.7 Another analysis of a private insurance claims database from 2007–2016 shows increasing rates of all food allergies, but also demonstrated an increase in claims for SA from ages 6 – 10 years old.34 A more recent study analyzing information from a national administrative claims database found that while there was an increase in ED visits over the last decade for shellfish, there were also increases for all the other top food allergies with peanuts being most common for ED visits.35 It is important to note though that both studies were limited to patients with insurance or Medicare Advantage and excluded data from families who were uninsured or had Medicaid.

A concerning finding in our study is that a significant proportion of SA pediatric patients have had more than one lifetime food allergy related ED visit and more than one-third have been treated with an epinephrine auto-injector in their life time. Despite these results, less than half of these patients carried a current epinephrine auto-injector indicating a large number of children at risk of life threatening allergic reactions without immediate access to treatment. This disparity in the carriage of epinephrine auto-injectors implies that greater education and awareness remains needed in the field of food allergy.

It is assumed by most physicians that there is a high rate of cross-reactivity for shellfish and if a patient is allergic to crustacean, they are likely allergic to mollusks as well. Perhaps the greatest attestation to this assumption is the fact that ICD-9 and ICD-10 do not have separate diagnosis codes for mollusk allergy or crustacean allergy.34 This study shows that the proportion of children with crustacean allergy who are also allergic to mollusk is less than 50%. Sicherer et. al. previously suggested that those who are crustacean allergic may be able to tolerate mollusks.13 These findings demonstrate the importance for clinicians to ascertain whether a patient is allergic to crustaceans or mollusk before recommending blanket avoidance of all shellfish. This will not only provide the patient more options in their diet but also help better understand the nature of shellfish allergy in the future.

There were increased odds of having shellfish, crustacean, or mollusk allergy among Black children versus White children which has been demonstrated in previous studies.3,36 Of note, there were no significant differences in odds of shellfish, crustacean, or mollusk allergy among different household incomes. This suggests race is a stronger predictor of the development of food allergy than socioeconomic status and that there may be a genetic predisposition for the development of SA. As shown in Figure E2, this appears to be true for each assessed race/ethnicity except for Asians. The difference in predicted probabilities of shellfish allergy between Asians from households earning >50K and Asians from households earning <50K is indeed statistically significant (p=0.015) Possible explanations for higher probability of shellfish allergy in higher income Asian households may be due increased chances of exposure or a higher likelihood of adopting a western diet and differences in self-reporting. The potential gene-environment interaction has previously been demonstrated in the case of peanut allergy37 but has not been carefully studied among SA patients.

The major limitation of our study is potential recall bias with a self-report survey and selection bias, as those with food allergy may be more likely to respond to surveys. The use of the AmeriSpeak panel, a sociodemographically and graphically representative sample of US households with children, was used to minimize some selection bias. This study could not assess shellfish specific SPT or sIgE levels to support diagnosis along with an adverse reaction history. This limitation was ameliorated as much as possible by implementing strict confirmatory diagnostic criteria, including stringent symptoms, to eliminate children with histories that are inconsistent with IgE-mediated allergy (i.e. intolerance or oral allergy syndrome). Lack of proper physician diagnosis may also have influenced epinephrine carriage rates. Another limitation to this study was the significantly lower number of subjects with mollusk allergy. While this is consistent with other studies both in the United States and around the world,13,22,38–41 this leads to correspondingly greater variability in estimates pertaining to mollusk allergy outcomes relative to crustacean allergy. Ingestion habits of children were not recorded, so it is possible that some children who had never ingested foods like mollusks were not considered allergic to that food.

Conclusion

SA affects 1.3% of children in the United States, with the most prevalence in children 6 – 17 years old. The present study closes a gap in the literature by examining the prevalence, distribution, and characteristics of shellfish allergic US children via a large, population-based survey, with a particular emphasis on comparing and contrasting the two main subgroups of shellfish allergy —crustacean and mollusk allergy. In summary, the average age of diagnosis of shellfish allergy was in adolescence at 16 years, crustacean allergy was more common than mollusk allergy in all age categories, more than half of pediatric patients visit an emergency room in their lifetime due to shellfish allergy, but less than half carry an epinephrine auto-injector. This study has improved our understanding of the epidemiology and presentation of shellfish allergy in the US pediatric population and highlighted areas of need for future study.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

1. What is already known about this topic?

Shellfish allergy (SA) can cause severe reactions including anaphylaxis and is among the most common food allergies in US children.

2. What does this article add to our knowledge?

This is the first comprehensive study specifically examining and comparing the characteristics of SA and its subtypes (crustacean and mollusk allergy) among US children, using a comprehensive sampling approach and a strict diagnostic algorithm to confirm self-reported SA prevalence, which is 1.3% with the most prevalence in children 6 – 17 years old.

3. How does this study impact current management guidelines?

While SA has been traditionally considered more of an adult food allergy, with the significant prevalence in this study, shellfish allergy should be aggressively assessed and managed in the pediatric population, with consideration of the importance of emergency medication carriage. Further delineation between crustacean versus mollusk allergy should be considered as well in the pediatric population.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of funding:

Helen Wang and Christopher Warren: Nothing to Disclose

R Gupta: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (R21AI135702-PI: Gupta)

CM Davis: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease; Allakos; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; DBV Technologies, Inc

References

- 1.Dunlop JH, Keet CA. Epidemiology of Food Allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2018;38(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, Jiang J, Blumenstock JA, Davis MM, et al. Prevalence and Severity of Food Allergies Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e185630. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, Smith B, Kumar R, Pongracic J, et al. The Prevalence, Severity, and Distribution of Childhood Food Allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):e9–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2183N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Estrada A, Silvers SK, Klein A, Zell K, Wang X-F, Lang DM. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis at a tertiary care center. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol 2017;118(1):80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvani M, Di Lallo D, Polo A, Spinelli A, Zappala D, Zicari AM. Hospitalizations for pediatric anaphylaxis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2008;21(4):977–983. doi: 10.1177/039463200802100422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webb LM, Lieberman P. Anaphylaxis: a review of 601 cases. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;97(1):39–43. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61367-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross MP, Ferguson M, Street D, Klontz K, Schroeder T, Luccioli S. Analysis of food-allergic and anaphylactic events in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121(1):166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopata AL, Kleine-Tebbe J, Kamath SD. Allergens and molecular diagnostics of shellfish allergy. Allergo J Int 2016;25(7):210–218. doi: 10.1007/s40629-016-0124-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nugraha R, Kamath SD, Johnston E, Zenger KR, Rolland JM, O’Hehir RE et al. Rapid and comprehensive discovery of unreported shellfish allergens using large-scale transcriptomic and proteomic resources. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;141(4):1501–1504.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pascal M, Grishina G, Yang AC, Sanchez-Garcia S, Lin J, Towle D et al. Molecular Diagnosis of Shrimp Allergy: Efficiency of Several Allergens to Predict Clinical Reactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015;3(4):521–529.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Chen Z-W, Hurlburt BK, Li GL, Zhang YX, Fei DX, et al. Identification of triosephosphate isomerase as a novel allergen in Octopus fangsiao. Mol Immunol 2017;85:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu C-J, Lin Y-F, Chiang B-L, Chow L-P. Proteomics and immunological analysis of a novel shrimp allergen, Pen m 2. J Immunol 2003;170(1):445–453. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12496430. Accessed April 30, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of seafood allergy in the United States determined by a random telephone survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;114(1):159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Matsuo H, Morita E. Cross-reactivity among shrimp, crab and scallops in a patient with a seafood allergy. J Dermatol 2006;33(3):174–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moonesinghe H, Mackenzie H, Venter C, Kilburn S, Turner P, Weir K, et al. Prevalence of fish and shellfish allergy: A systematic review. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol 2016;117(3):264–272.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, Blumenstock JA, Jiang J, Davis MM,et al. The Public Health Impact of Parent-Reported Childhood Food Allergies in the United States. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20181235. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Office for Coastal Management N. Coastal County Definitions Coastal County Aggregations Coastal Watershed Counties.; 2013. https://coast.noaa.gov/data/digitalcoast/pdf/qrt-coastal-county-definitions.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2019.

- 18.Disogra C, Cobb C, Chan E, Dennis JM. Calibrating Non-Probability Internet Samples with Probability Samples Using Early Adopter Characteristics. http://www.asasrms.org/Proceedings/y2011/Files/302704_68925.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2019.

- 19.Barlas FM, Thomas RK, Buttermore N. Scientific Surveys Based on Incomplete Sampling Frames and High Rates of Nonresponse. Surv Pract 2015;8(5). www.surveypractice.org. Accessed April 22, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau CH, Springston EE, Smith B, Pongracic J, Holl JL, Gupta RS. Parent report of childhood shellfish allergy in the United States. Allergy Asthma Proc 2012;33(6):474–480. doi: 10.2500/aap.2012.33.3610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chokshi NY, Maskatia Z, Miller S, Guffey D, Minard CG, Davis CM. Risk factors in pediatric shrimp allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc 2015;36(4):65–71. doi: 10.2500/aap.2015.36.3852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Per Capita Consumption.; 2015. https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/Assets/commercial/fus/fus15/documents/09_PerCapita2015.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- 23.Wu TC, Tsai TC, Huang CF, Chang FY, Lin CC, Huang IF,et al. Prevalence of food allergy in Taiwan: a questionnaire-based survey. 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02820.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Pei-Chi Shek L, Ann Cabrera-Morales E, Soh SE, Gerez I, Ng PZ, Yi FC, et al. A population-based questionnaire survey on the prevalence of peanut, tree nut, and shellfish allergy in 2 Asian populations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:324–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiang WC, Kidon MI, Liew WK, Goh A, Tang JP, Chay OM. The changing face of food hypersensitivity in an Asian community. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02752.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Iwamoto M, Ayers T, Mahon BE, Swerdlow DL. Epidemiology of Seafood-Associated Infections in the United States. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010; 23(2): 399–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beyer K, Morrowa E, Li X-M, Bardina L, Bannon GA, Burks AW, et al. Effects of cooking methods on peanut allergenicity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107(6):1077–1081. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J, Lee JY, Han Y, Ahn K. Significance of Ara h 2 in clinical reactivity and effect of cooking methods on allergenicity. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol 2013;110(1):34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Fiocchi A. Rare, medium, or well done? The effect of heating and food matrix on food protein allergenicity. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;9(3):234–237. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32832b88e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bloom KA, Huang FR, Bencharitiwong R, Bardina L, Ross A, Sampson HA, et al. Effect of heat treatment on milk and egg proteins allergenicity. doi: 10.1111/pai.12283 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Nakamura A, Watanabe K, Ojima T, Ahn DH, Saeki H. Effect of Maillard Reaction on Allergenicity of Scallop Tropomyosin. 2005. doi: 10.1021/jf0502045 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Nakamura A, Sasaki F, Watanabe K, Ojima T, Ahn DH, Saeki H. Changes in Allergenicity and Digestibility of Squid Tropomyosin during the Maillard Reaction with Ribose. 2006. doi: 10.1021/jf061070d [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.https://www.seafoodhealthfacts.org/seafood-choices/overview-us-seafood-supply, Accessed 9/2/2019

- 34.Mcgowan E, Keet CA. Prevalence of self-reported food allergy in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2010. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132(5):1216–9.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Health AF, Paper W. An Analysis of Private Claims Data Food Allergy in the United States: Recent Trends and Costs. 2017;(November). doi: 10.1186/2045-7022-2-25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motosue MS, Bellolio MF, Van Houten HK, Shah ND, Campbell RL. National trends in emergency department visits and hospitalizations for food-induced anaphylaxis in US children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2018;29(5):538–544. doi: 10.1111/pai.12908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor-Black S, Wang J. The prevalence and characteristics of food allergy in urban minority children. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol 2012;109(6):431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koplin JJ, Peters RL, Ponsonby A, Gurrin LC, Hill D, Tang ML, et al. Increased risk of peanut allergy in infants of Asian-born parents compared to those of Australian-born parents. Allergy. 2014;69:1639–1647. doi: 10.1111/all.12487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner P, Ng I, Kemp A, Campbell D. Seafood allergy in children: a descriptive study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2011;106:494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lao-Araya M, Trakultivakorn M. Prevalence of food allergy among preschool children in northern Thailand. Pediatr Int 2012;54:238–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2011.03544.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.K Le TT, Nguyen DH, L Vu AT, Ruethers T, Taki AC, Lopata AL, et al. A cross-sectional, population-based study on the prevalence of food allergies among children in two different socio-economic regions of Vietnam. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2019;30:348–355. doi: 10.1111/pai.13022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.