Abstract

Spatial frequency analysis (SFA) is a quantitative ultrasound method that characterizes tissue organization. SFA has been used for research involving tendon injury, but may prove useful in similar research involving skeletal muscle. As a first step, we investigated if SFA could detect known architectural differences within hamstring muscles. Ultrasound B-mode images were collected bilaterally at locations corresponding to proximal, mid-belly, and distal thirds along the hamstrings from 10 healthy participants. Images were analyzed in the spatial frequency domain by applying a two-dimensional Fourier Transform in all 6.5 x 6.5 mm kernels in a region of interest corresponding to the central portion of the muscle. SFA parameters (peak spatial frequency radius (PSFR), maximum frequency amplitude (Mmax), sum of frequencies (Sum), and ratio of Mmax to Sum (Mmax%)) were extracted from each muscle location and analyzed by separate linear mixed effects models. Significant differences were observed proximo-distally in PSFR (p = 0.039), Mmax (p < 0.0001), and Sum (p < 0.0001), consistent with architectural descriptions of the hamstring muscles. These results suggest that SFA can detect regional differences of healthy tissue structure within the hamstrings—an important finding for future research in regional muscle structure and mechanics.

Keywords: ultrasound, hamstrings, spatial frequency analysis, musculoskeletal, anatomy

Introduction

The hamstrings are comprised of three distinct muscles—biceps femoris, semitendinosus (ST), and semimembranosus (SM)—that function as hip extensors and knee flexors. Although all three contribute to the same overall function, each muscle has unique structure allowing for differentiation in dynamic tasks.1-5 For example, it has been suggested that the ST muscle is better suited to operate at longer lengths and higher velocities than the BF and SM muscles due to its more parallel-fiber arrangement and longer fascicles.3,4,6 In contrast, the BF and SM muscles have larger pennation angles relative to the ST muscle, which allows for more force-generating fibers to be packed into each fascicle.3,7,8 Differences in architectural features along each muscle have also been observed,9,10 which may indicate that different regions within the same muscle may respond differently to loading.11,12

Characterization of muscle structure and tissue properties has many important implications in research and clinical care, for example with respect to biomechanical modelling13,14 or hamstring strain injury risk.15,16 Recently, studies have investigated regional variation in mechanical properties17 and activation levels18 along the hamstrings in response to stretching and various exercises used in injury prevention programs. The role that regional variation of tissue organization of architectural arrangement, tissue properties, and muscle activation may have on factors influencing whole muscle mechanics may have important implications on regions of the hamstring muscles that may be the most susceptible to injury.12

Several studies have characterized different structural features of the hamstrings, such as muscle thickness, pennation angle, and fascicle length, using methods such as cadaveric dissection and ultrasound (US) imaging.9,10 US B-mode imaging is reliable in characterizing different architectural measures compared to cadaveric dissection in fascicle length and pennation angle19,20 and muscle thickness and muscle length21 in hamstring muscles, making it a useful tool for assessing muscle structure and function in vivo. Studies utilizing quantitative US methods in skeletal muscle have shown utility in assessing structural adaptations to exercise training, changes due to injury, and pathology.15,22-27

Spatial frequency analysis (SFA) is a quantitative US method, which analyzes the anisotropic B-mode speckle pattern arising from within a tissue type in the spatial frequency domain. Parameters related to prominent spatial frequencies measure the overall organization of the underlying tissue hierarchy. SFA has been utilized mainly in tendons to date, which has proven useful in characterizing structural changes in tendon pathologies.28-30 Skeletal muscle has a similar hierarchical structure to tendon with normal, healthy tissue consisting of parallel striations of the hypoechoic fibers and hyperechoic perimysium observed in B-mode images. A recent investigation adapted and extended SFA for use in skeletal muscle, showing it to have good intra- and inter-rater reliability.31

The next step in determining the usefulness of SFA in research involving muscle tissue is to determine whether it detects known architectural differences in healthy muscle. Thus, the goal of this study was to examine whether SFA could characterize known structural differences within the hamstring muscles. Specific spatial frequency parameters, for example the peak spatial frequency radius (PSFR), reported in tendon research have coincided with the spacing between collagen bundles28 with increased spacing between hyperechoic bundles corresponding to a lower PSFR value. Due to the architectural differences in pennation angle between and along the hamstring muscles, it was hypothesized that SFA parameters would be different between muscles and along individual muscles, consistent with previous descriptions of hamstring structure and architecture3,4,9,10,32 and concurrently estimated from image analysis.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Healthy male and female individuals were recruited for this investigation. To be included for the study, participants had to be between 18-35 years and participate in regular physical activity at least 3 days per week or in recreational sport. Participants were excluded if they had a history of lower extremity surgery or hamstring strain injury or were currently pregnant. This study and all procedures were approved by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. All participants provided written informed consent.

Image Acquisition

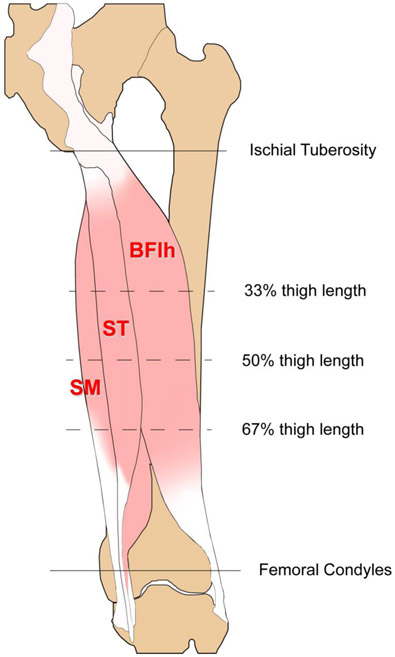

Participants were positioned prone on an exam table, supported in a neutral position, and remained relaxed with no muscular contraction. Skin markings were made at 33%, 50%, and 67% of the thigh length measured from the ischial tuberosity to the midpoint between the femoral condyles (Figure 1). These marks corresponded to approximately proximal, mid-belly, and distal regions of the hamstring muscles, respectively.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the image acquisition procedure. Participants were positioned prone on an exam table and the thigh length from the ischial tuberosity to the midpoint between the femoral condyles was measured. Marks were made at proximal, mid-belly, and distal (33%, 50% and 67%, respectively) locations along the thigh bilaterally. Images were acquired at each location on both limbs for each participant across all three muscles. BFlh = biceps femoris long head, ST = semitendinosus, SM = semimembranosus

Ultrasound images were collected by an experienced sonographer (18+ years of US experience with 5+ years in musculoskeletal US) using a commercial US system (Aixplorer, Supersonic Imagine, Weston, FL) with a linear array transducer (2-10 MHz, 38 mm width). Each muscle was first visualized in a transverse view at each location to ensure correct positioning. Longitudinal B-mode images were then captured bilaterally for the biceps femoris long head (BFlh), ST, and SM muscles at each of the three skin-marked locations. The longitudinal direction was determined by adjusting the transducer until the probe was oriented along the fascicle direction.33 A liberal amount of acoustic gel was placed on the thigh and minimal transducer pressure was applied to the muscle in order to avoid tissue compression. All US machine settings were kept constant for all image acquisitions across all participants. The depth was set to 5 cm, dual transmit foci depths were at 2 and 3 cm (corresponding to approximately the center of the muscle34), and the gain set at 38% for all images.

Image Analysis

Static B-mode images were analyzed using custom MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) algorithms. For each location across the three muscles, a polygonal region of interest (ROI) was drawn about the central portion of the muscle to best capture its representative architecture (Figure 2).35 The lateral aspect of the ROI was kept a minimum of 0.5 cm from the image edges in order to preserve lateral resolution.36 The ROIs were visually checked between limbs to ensure the ROIs spanned similar depths within the muscle. A single investigator (S.K.C.) drew all ROIs across all images. SFA parameters were previously shown to have excellent reliability when performed by a single rater.31

Figure 2.

Representative B-mode image and SFA procedure. A) Longitudinal B-mode image taken from the biceps femoris long head at the mid-belly location as visual reference for characteristic parallel striations of the hypoechoic fibers and hyperechoic perimysium. B) SFA procedure and overlay of representative output of peak spatial frequency radius (PSFR) from all kernels. The B-mode image was imported into MATLAB 2019b and the ROI drawn about the central portion of the image with the edges approximately 0.5 cm from the image edges. All kernels within the ROI were analyzed, SFA parameters extracted, and averaged across the entire ROI. Note that the kernels corresponded to the maximum lateral and axial locations of the ROI, but the SFA parameter value is attributed to the centroid of the 96 x 96 pixel square. Therefore, a gap corresponding to 48 pixels is seen between the SFA parameter values and the edge of the ROI. The original B-mode images have been cropped only to exclude study data, including dates and subject IDs, but have not been modified in any other way.

SFA was performed similar to previous descriptions28,29,31 with the exception of an increased ROI size. All possible 96 x 96 pixel (~6.6 mm) sub-images (kernels) within the ROI were analyzed in the spatial frequency domain. Briefly, 2D Fourier Transforms were applied to each kernel after zero-padding to 128 x 128 samples to increase frequency sampling. A 2D high pass filter (−3 dB cut-off about 1.0 mm−1) was applied to attenuate low spatial frequency artifacts. A subset of spatial frequency parameters originally proposed28 were calculated and averaged over all kernels within the ROI of an image, resulting in a single value per parameter per image. Spatial frequency parameters included peak spatial frequency radius (PSFR), Mmax, Mmax%, and Sum. PSFR is defined as the distance (in the frequency domain) from the origin to the peak of maximum frequency amplitude. Mmax is the corresponding amplitude observed at the peak spatial frequency. The Sum parameter is the sum of all samples in the kernel. Mmax% is the ratio of the Mmax parameter to the Sum parameter. A mathematical description of each parameter with the physiological correlate is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mathematical formulations and physiological implications of extracted spatial frequency parameters. Adapted from Crawford et al. (2020).

| Parameter | Mathematical Formulation | Physiological Implication(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Peak spatial frequency radius (PSFR) | , where umax, vmax are directional vectors in frequency domain | Most dominant spacing between hyperechoic perimysium of the muscle fascicles and hypoechoic muscle fibers |

| Mmax | max(F(u, v)) | Amplitude (“strength”) of the most prominent fascicular banded pattern |

| Mmax % | max(F(u, v)) / ʃʃ F(u, v)dudv | Contribution of most prominent fascicle pattern compared to total (speckle) background |

| Sum | ʃʃ F(u, v)dudv | Equivalent to total image brightness |

B-mode images were also manually digitized to extract pennation angles using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Pennation angles were measured as the angle a fascicle inserted into the superficial aponeurosis for consistency with previous investigations.9,10 From each image, pennation angle was measured for three separate fascicles. The average of these three measures was used for subsequent analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Separate linear mixed effects models were performed to determine the influence of the fixed effects of muscle and location and the muscle x location interaction on each parameter. To account for within-subject repeated measures of limb on each parameter, subject was input into the model as a random effect. Significant interactions and main effects were followed with pairwise post hoc Tukey tests. In the event of a significant interaction, only comparisons between locations within the same muscle are presented in the Results as these are both clinically and anatomically meaningful.9,17 Pennation angle for each muscle and location were summarized by means and standard deviations for comparisons with previous investigations.9,10 Separate Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between the measured pennation angles and extracted SFA parameters values. The strength of the associations were defined as weak (∣r∣ < 0.25), moderate (0.25 ≤ ∣r∣ < 0.50), and strong (∣r∣ ≥ 0.50). Tests of significance were also performed to determine if the relationships were significant. A priori significance was set at α=0.05 for all analyses. All statistical analyses were performed in R software (R Core Development Team).

Results

Ten volunteers (4 females, 6 males) participated in this study resulting in a total of 180 images (10 subjects x 2 limbs x 3 muscles x 3 locations) included for analysis. Participants had a mean ± standard deviation age of 23.4 ± 1.2 years, body mass 69.9 ± 9.3 kg, height 174.2 ± 6.7 cm, and BMI 23.0 ± 3.0 kg/m2. The means and standard deviation of pennation angles measured from the images are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means ± standard deviation of pennation angles (degrees) measured from the superficial aponeurosis by each muscle and location combination. The mean of three representative fascicles was taken as the measure for a single image and used for subsequent analysis. The whole muscles means and standard deviations were calculated as the means across all three locations (proximal, mid-belly, and distal) for each muscle.

| Proximal | Mid-belly | Distal | Whole Muscle Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biceps Femoris Long Head | 10.9 ± 3.2 | 13.7 ± 2.3 | 15.5 ± 2.1 | 13.4 ± 3.2 |

| Semitendinosus | 7.6 ± 2.6 | 7.7 ± 2.0 | 9.2 ± 2.8 | 8.2 ± 2.6 |

| Semimembranosus | 10.6 ± 2.1 | 16.6 ± 4.5 | 19.0 ± 3.1 | 15.4 ± 4.8 |

Peak Spatial Frequency Radius (PSFR)

A significant muscle x location interaction effect for PSFR was observed (F = 2.579, p = 0.04; Figure 3A). Post hoc tests showed no significant differences within the BFlh or SM muscles (p-value’s > 0.18 for all within-muscle comparisons, Supplementary Material Table 1). Within-muscle differences were observed in the ST muscle with the distal region having a lower PSFR than the proximal (p = 0.01) and mid-belly regions (p = 0.003). The proximal region in the ST muscle was not different from the mid-belly location (p = 0.99). A significant moderate, negative relationship was observed between the measured pennation angles and PSFR (r = −0.49, p < 0.001; Figure 4A).

Figure 3.

Least square means with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the spatial frequency parameters for each hamstring muscle location. The muscles are plotted on the abscissa with the proximal, mid-belly, and distal locations represented from left to right for each muscle. A) Peak spatial frequency radius (PSFR), B) Mmax, C) Mmax%, and D) Sum. Significance (p < 0.05) along the muscle is noted with an asterisk (*). The inset in C) shows the least square means and 95% CI of the main effect of muscle of Mmax% with an asterisk denoting differences between the hamstring muscles. BFlh = biceps femoris long head, ST = semitendinosus, SM = semimembranosus

Figure 4.

Scatter plots and Pearson correlation relationships plotted with 95% confidence interval. A) Peak spatial frequency radius (PSFR). B) Mmax. C) Mmax%. D) Sum. Abbreviations: PA = pennation angle, deg = degrees, a.u. = arbitrary units.

Mmax

A significant muscle x location interaction effect was observed for Mmax (F = 10.494, p < 0.0001; Figure 3B). No differences in Mmax were observed along the BFlh muscle (p-value’s > 0.13 for all within-muscle comparisons, Supplementary Material Table 2). Post hoc tests showed Mmax in the ST muscle was greater in the proximal location compared to the mid-belly (p = 0.003) and distal locations (p < 0.001). For the SM muscle, Mmax was larger in the proximal location compared to the distal location (p = 0.007). No relationship was observed between Mmax and pennation angle (r = 0.10, p = 0.17; Figure 4B).

Mmax%

No significant effects of the interaction of muscle x location (F = 1.457, p = 0.218) or of the main effect of location (F = 0.281, p = 0.755) were observed on Mmax% (Figure 3C). However, the main effect of muscle was observed to be significant for Mmax% (F = 8.909, p < 0.001). Post hoc tests of the main effect of muscle showed Mmax% was greater in the SM muscle compared to the BFlh (p = 0.01) and ST (p < 0.001) (Figure 3C, inset). No differences were observed in Mmax% between the ST and BFlh muscles (p = 0.50). A significant moderate, positive relationship was observed between Mmax% and pennation angle (r = 0.32, p < 0.001; Figure 4C).

Sum

A significant muscle x interaction effect was observed in Sum (F = 6.651, p < 0.0001; Figure 3D). Post hoc tests showed no differences in Sum along the length of the BFlh muscle (p > 0.94 for all within-muscle comparisons, Supplementary Material Table 3). For the ST and SM muscles, Sum was greater in the proximal location compared to the mid-belly (p-value’s < 0.01) and distal locations (p-value’s < 0.001). A significant but weak, negative relationship was observed between Sum and pennation angle (r = −0.23, p = 0.002; Figure 4D).

Discussion

This investigation used spatial frequency parameters to characterize muscle structure between different anatomical regions within the hamstring muscles. We expected SFA parameters to be different between muscles and along individual muscles, reflecting previous descriptions of hamstring structure and architecture.4,9,32 We observed differences in PSFR, Mmax, and Sum parameters along the muscle length in individual hamstring muscles.

Although SFA has been used in various studies investigating healthy versus tendinopathic tissue structure,28,29,37 there have been no studies to date that have related spatial frequency parameters to skeletal muscle organization. The PSFR parameter reflects the spacing of the most dominant banded fascicular pattern, which in muscle is thought to correspond to the spacing between the perimysium. As such, PSFR is expected to differ with skeletal muscle architecture. For example, muscles with a larger pennation angle have more contractile fibers packed within the fascicles,7,8 which would result in a lower PSFR value. We did observe a significant inverse relationship between pennation angle and extracted PSFR values, indicating that PSFR decreased as pennation angle increased. This relationship could prove meaningful in future investigations of muscle adaptation to exercise, injury, or pathology. Mmax is the maximum amplitude corresponding to the peak spatial frequency location. We did not observe any relationships between Mmax and pennation angle. This could indicate that Mmax is independent of pennation angle and may be more sensitive to different tissue types along the muscle (see discussion below for more detail). The Sum parameter is mathematically defined as the sum of all kernel samples. With regard to the B-mode image, this would indicate that a brighter B-mode image would have a larger Sum value with differences in image brightness and perhaps relate to more tendinous portions of the tissue, since the overall backscatter of tissue is related to its density.38-40 We observed a negative relationship between Sum and pennation angle. This is likely due to the more hypoechoic fibers packed within the fascicles at greater pennation angles, thereby reducing the overall brightness of the image. The Mmax% parameter (ratio of Mmax and Sum) indicates the strength of the most dominant spatial frequency compared to the background. Assuming Mmax% relates to the collagen content (i.e. perimysium) relative to the muscle fibers, then it might be expected that a muscle with a larger percentage of contractile tissue (hypoechoic fibers) would have a larger Mmax% value. In this case, the overall brightness of the image would be lower due to the greater percentage of hypoechoic fibers resulting in a smaller denominator and an overall larger Mmax% value. We observed a positive relationship between Mmax% and pennation angle, which gives preliminary support to this idea.

Biceps Femoris Long Head

We did not observe any differences along the length of the BFlh in any spatial frequency parameter. Previous investigations in the variation of pennation angle or fascicle length in the BFlh muscle showed no differences in pennation angle at 40 and 60% or 50 and 70% of the muscle length.9,10 These locations relative to the ischial tuberosity and femoral condyles correspond to approximately the same locations in our study (33, 50, and 67% of the thigh length from the ischial tuberosity), which could explain why no differences were observed in SFA parameters along the BFlh. Furthermore, the measured pennation angles in the current study (Table 2) are in agreement with those previously reported along the length of the BFlh10 and the ST muscles.3 Considering the consistent architectural measures previously reported and observed in the current study along the length of the BFlh, the lack of significant findings across all parameters along the BFlh appears to be consistent with the structural organization of this muscle.

Semitendinosus

SFA characterized proximo-distal differences along the ST muscle in the PSFR, Mmax, and Sum parameters. With respect to the pennation angle, previous cadaveric dissection studies have shown that the distal portion (75% of the muscle-tendon length) of the ST muscle has a larger pennation angle compared to the more proximal locations (40 and 60% of the muscle-tendon length),9 which is consistent with our extracted PSFR values and measured pennation angles (Table 2). Additionally, a previous investigation of the anatomy of the hamstring muscles showed that the ST was separated into two distinct compartments, separated by a tendinous inscription.32 The fascicles within the proximal compartment of the ST originated from three different locations and inserted into the tendinous inscription at approximately 30% of the muscle length from the ischial tuberosity.32,41 In the current study, we noted differences in Mmax between the proximal and mid-belly and proximal and distal locations, but not between the mid-belly and distal locations within the ST. It is possible that the differences observed in Mmax along the ST muscle may reflect the fascicular insertions into the tendinous inscription proximally compared to those observed more distally.

Muscle with more fibrotic tissue has a larger echogenicity compared to healthy muscle tissue.27 In the current investigation involving healthy muscle, a larger Sum value could reflect more tendinous fibers inserting more acutely. In a study investigating hamstring muscle strains using computed tomography, it was observed that the proximal MTJ of the ST muscle spans the first 31% of the muscle length,42 which is consistent with the differences we observed in the Sum parameter between the proximal and other two locations within the ST muscle.

Semimembranosus

Direct comparisons about the proximo-distal variability in SM architectural is difficult to make since many studies have either measured from a single location or calculated the mean of several locations prior to subsequent analyses.3,4,12,20,43 However, in two cadaveric studies, the pennation angle of the SM (N = 8 limbs) was reported as 16 ± 2.4 degrees3 and (N = 22 limbs) 15.1 ± 3.4 degrees4 with these measures calculated from the mean of proximal, middle, and distal locations along the SM. We calculated the whole muscle mean of pennation angle measures across all three locations along the SM as 15.4 ± 4.9 degrees, which is consistent with these previous studies. One study used magnetic resonance imaging to infer the orientation of muscle fascicles and found that pennation angle in the SM ranged from 10 to 20 degrees proximo-distally.44 These measures were taken from a single cadaver limb so it was unclear if this finding is generalizable. We measured pennation angles proximo-distally in the SM muscle from 10.6 to 19.0 degrees (Table 2), which is in agreement with the measures reported in the single cadaver limb.

Similar to the BFlh muscle, we did not observe any differences in PSFR along the SM muscle. It is unclear why no differences were observed in PSFR along the SM muscle. It has previously been observed in computed tomography and ultrasound studies that the first fibers of the SM muscle inserting into the tendon originate at approximately 30% of the muscle length.42,45 It is possible that with the imaging location of 33% of the thigh length, we could have included the musculotendinous junction within our ROI. The effects of different tissue types on SFA parameters has not been investigated, but future investigations should attempt to elucidate this phenomenon.

The SM muscle has three different compartments with the proximal and distal compartments having different fascicular orientations and primary nerve branches.32 The middle compartment has been suggested to be a constituent of either the proximal or the distal partition, which suggests that this middle compartment is architecturally similar to the other two compartments. Despite non-significant observations in PSFR along the SM muscle, we did observe differences in Mmax between the proximal and distal locations. These findings could reflect the compartmental differences in the SM muscle, especially as it relates to the musculotendinous junction. Similar to findings along the ST muscle, we also observed differences in the Sum parameter in the SM muscle between the proximal and mid-belly and proximal and distal locations (Figure 1D). As noted previously, the Sum indicates the image brightness and may be indicative of more tendinous tissue. Since the first fibers of the SM muscle insert into the tendon at approximately 30% of the muscle length,42,45 this transitional region of the musculotendinous junction could explain the larger Sum value at the proximal region.

We did not observe any significant interaction between muscle and location in the Mmax% parameter. A recent study showed minimal change in collagen content relative to muscle tissue along the length of the SM muscles in mice.46 Assuming Mmax% relates to the collagen content (i.e. perimysium) relative to the muscle fibers, then the current findings are consistent with the findings in collagen content along the length of the SM muscles in mice. Although there were no proximo-distal differences observed in Mmax%, we did observe differences between SM and both the BFlh and ST muscles. This finding could reflect the differences in the whole muscle physiologic cross-sectional area (PCSA) between the hamstring muscles. Anatomical dissection showed that the SM had mean fascicular PCSA (calculated by dividing the volume of each fascicle by its length) larger than both the BFlh and ST muscles4,32 with the PCSA of the SM muscle being approximately 50 and 100% greater than that of the BFlh and ST muscles, respectively.3,32 The differences in Mmax% between different hamstring muscles may reflect architectural differences, particularly of the larger percentage of contractile fibers relative to the hyperechoic perimysium observed in B-mode images, that may impact functional force generating capacity.

Study Limitations

The current investigation had a relatively small sample size of 10 total subjects (20 limbs). Due to the sample size, we could not explore any sex differences in SFA parameters. Additionally, this sample only included young individuals so these findings may not directly relate to older individuals due to age-related muscle adaptations such as fatty filtration47-49

Conclusion

This is the first investigation to study differences between muscle tissue structure using the SFA method. Differences between muscles and along the muscles were observed in the extracted parameters. Physiological explanations of spatial frequency parameter differences were proposed. These results reflect known regional and anatomical differences between and within muscles of the hamstrings. These analyses may prove to be a useful complement in future investigations involving US imaging following hamstring strain injury and rehabilitation or in response or various modes of training. Future studies will attempt to determine relationships between SFA parameters and measures of hamstring muscle architecture, particularly during passive and active ranges of motion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Funding for this work was provided by NBA & GE Healthcare Orthopedics and Sports Medicine Collaboration and by the Clinical and Translational Science Award Program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR002373 and TL1TR002375.

References

- 1.Thelen DG, Chumanov ES, Hoerth DM, et al. Hamstring muscle kinematics during treadmill sprinting. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005; 37: 108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chumanov ES, Heiderscheit BC, Thelen DG. The effect of speed and influence of individual muscles on hamstring mechanics during the swing phase of sprinting. J Biomech 2007; 40: 3555–3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellis E, Galanis N, Kapetanos G, et al. Architectural differences between the hamstring muscles. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2012; 22: 520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward SR, Eng CM, Smallwood LH, et al. Are current measurements of lower extremity muscle architecture accurate? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467: 1074–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azizi E, Deslauriers AR. Regional heterogeneity in muscle fiber strain: The role of fiber architecture. Front Physiol 2014; 5: 303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieber RL, Fridén J. Functional and clinical significance of skeletal muscle architecture. Muscle Nerve 2000; 23: 1647–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gans C. Fiber architecture and muscle function. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 1982; 10: 160–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narici M. Human skeletal muscle architecture studied in vivo by non-invasive imaging techniques: Functional significance and applications. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 1999; 9: 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kellis E, Galanis N, Natsis K, et al. Muscle architecture variations along the human semitendinosus and biceps femoris (long head) length. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2010; 20: 1237–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tosovic D, Muirhead JC, Brown JMM, et al. Anatomy of the long head of biceps femoris: An ultrasound study. Clin Anat 2016; 29: 738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silder A, Reeder SB, Thelen DG. The influence of prior hamstring injury on lengthening muscle tissue mechanics. J Biomech 2010; 43: 2254–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kellis E. Intra- and Inter-Muscular Variations in Hamstring Architecture and Mechanics and Their Implications for Injury: A Narrative Review. Sport Med 2018; 48: 2271–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehorn MR, Blemker SS. The effects of aponeurosis geometry on strain injury susceptibility explored with a 3D muscle model. J Biomech 2010; 43: 2574–2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiorentino NM, Blemker SS. Musculotendon variability influences tissue strains experienced by the biceps femoris long head muscle during high-speed running. J Biomech 2014; 47: 3325–3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmins RG, Shield AJ, Williams MD, et al. Biceps femoris long head architecture: A reliability and retrospective injury study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015; 47: 905–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timmins RG, Bourne MN, Shield AJ, et al. Short biceps femoris fascicles and eccentric knee flexor weakness increase the risk of hamstring injury in elite football (soccer): A prospective cohort study. Br J Sports Med 2016; 50: 1524–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyamoto N, Kimura N, Hirata K. Nonuniform distribution of passive muscle stiffness within hamstring. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2020; 30: 1729–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegyi A, Csala D, Péter A, et al. High-density electromyography activity in various hamstring exercises. Scand J Med Sci Sport 2019; 29: 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chleboun GS, France AR, Crill MT, et al. In vivo measurement of fascicle length and pennation angle of the human biceps femoris muscle. Cells Tissues Organs 2001; 169: 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwah LK, Pinto RZ, Diong J, et al. Reliability and validity of ultrasound measurements of muscle fascicle length and pennation in humans: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Physiology 2013; 114: 761–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kellis E, Galanis N, Natsis K, et al. Validity of architectural properties of the hamstring muscles: Correlation of ultrasound findings with cadaveric dissection. J Biomech 2009; 42: 2549–2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Potier TG, Alexander CM, Seynnes OR. Effects of eccentric strength training on biceps femoris muscle architecture and knee joint range of movement. Eur J Appl Physiol 2009; 105: 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santos R, Valamatos MJ, Mil-Homens P, et al. Muscle thickness and echo-intensity changes of the quadriceps femoris muscle during a strength training program. Radiography 2018; 24: e75–e84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourne MN, Duhig SJ, Timmins RG, et al. Impact of the Nordic hamstring and hip extension exercises on hamstring architecture and morphology: Implications for injury prevention. Br J Sports Med 2017; 51: 469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao J, Memmott B, Poulson J, et al. Quantitative Ultrasound Imaging to Assess Skeletal Muscles in Adults with Multiple Sclerosis: A Feasibility Study. J Ultrasound Med 2019; 38: 2915–2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pillen S, Scholten RR, Zwarts MJ, et al. Quantitative skeletal muscle ultrasonography in children with suspected neuromuscular disease. Muscle and Nerve 2003; 27: 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pillen S, Tak RO, Zwarts MJ, et al. Skeletal Muscle Ultrasound: Correlation Between Fibrous Tissue and Echo Intensity. Ultrasound Med Biol 2009; 35: 443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bashford GR, Tomsen N, Arya S, et al. Tendinopathy discrimination by use of spatial frequency parameters in ultrasound B-mode images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2008; 27: 608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kulig K, Landel R, Chang YJ, et al. Patellar tendon morphology in volleyball athletes with and without patellar tendinopathy. Scand J Med Sci Sport 2013; 23: e81–e88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cassel M, Risch L, Mayer F, et al. Achilles tendon morphology assessed using image based spatial frequency analysis is altered among healthy elite adolescent athletes compared to recreationally active controls. J Sci Med Sport 2019; 22: 882–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawford SK, Lee KS, Bashford GR, et al. Intra-session and inter-rater reliability of spatial frequency analysis methods in skeletal muscle. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0235924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodley SJ, Mercer SR. Hamstring muscles: Architecture and innervation. Cells Tissues Organs 2005; 179: 125–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pimenta R, Blazevich AJ, Freitas SR. Biceps femoris long-head architecture assessed using different sonographic techniques. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2018; 50: 2584–2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maurits NM, Bollen AE, Windhausen A, et al. Muscle ultrasound analysis: Normal values and differentiation between myopathies and neuropathies. Ultrasound Med Biol 2003; 29: 215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blazevich AJ, Gill ND, Zhou S. Intra- and intermuscular variation in human quadriceps femoris architecture assessed in vivo. J Anat 2006; 209: 289–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaidman CM, Holland MR, Anderson CC, et al. Calibrated quantitative ultrasound imaging of skeletal muscle using backscatter analysis. Muscle and Nerve 2008; 38: 893–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kulig K, Chang Y-J, Winiarski S, et al. Ultrasound-based tendon micromorphology predicts mechanical characteristics of degenerated tendons. Ultrasound Med Biol 2016; 42: 664–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faran JJ. Sound Scattering by Solid Cylinders and Spheres. J Acoust Soc Am 1951; 23: 405–418. [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Brien PD, O’Brien WD, Rhyne TL, et al. Relation of ultrasonic backscatter and acoustic propagation properties to myofibrillar length and myocardial thickness. Circulation 1995; 91: 171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Insana MF, Wagner RF, Brown DG, et al. Describing small-scale structure in random media using pulse-echo ultrasound. J Acoust Soc Am 1990; 87: 179–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Made AD, Wieldraaijer T, Kerkhoffs GM, et al. The hamstring muscle complex. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23: 2115–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrett WE, Rich FR, Nikolaou PK, et al. Computed tomography of hamstring muscle strains. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1989; 21: 506–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charles JP, Suntaxi F, Anderst WJ. In vivo human lower limb muscle architecture dataset obtained using diffusion tensor imaging. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0223531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scott SH, Engstrom CM, Loeb GE. Morphometry of human thigh muscles. Determination of fascicle architecture by magnetic resonance imaging. J Anat 1993; 182: 249–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balius R, Pedret C, Iriarte I, et al. Sonographic landmarks in hamstring muscles. Skeletal Radiol 2019; 48: 1675–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Binder-Markey BI, Broda NM, Lieber RL. Intramuscular Anatomy Drives Collagen Content Variation Within and Between Muscles. Front Physiol 2020; 11: 293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cutlip RG, Baker BA, Hollander M, et al. Injury and adaptive mechanisms in skeletal muscle. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2009; 19: 358–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Narici M V, Bordini M, Cerretelli P. Effect of aging on human adductor pollicis muscle function. J Appl Physiol 1991; 71: 1277–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindle RS, Metter EJ, Lynch NA, et al. Age and gender comparisons of muscle strength in 654 women and men aged 20-93 yr. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Kenward MG, Roger JH. An improved approximation to the precision of fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Comput Stat Data Anal 2009; 53: 2583–2595. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.