Abstract

Abstract

One in every two humans is having Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in stomach causing gastric ulcer. Emergence of several drugs in eliminating H. pylori has paved way for emergence of multidrug resistance in them. This resistance is thriving and thereby necessitating the need of a potent drug. Identifying a potential target for medication is crucial. Bacterial 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-enosyl homocysteine nucleosidase (MTAN) is a multifunctional enzyme that controls seven essential metabolic pathways. It functions as a catalyst in the hydrolysis of the N-ribosidic bond of adenosine-based metabolites: S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), 5′-methylthioadenosine (MTA), 5′-deoxyadenosine (5′-DOA), and 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine. H. pylori unlike other bacteria and humans utilises an alternative pathway for menaquinone synthesis. It utilises Futosiline pathway for menaquinone synthesis which are obligatory component in electron transport pathway. Therefore, the enzymes functioning in this pathway represent them-self as a point of attack for new medications. We targeted MTAN protein of H. pylori to find out a potent natural hit to inhibit its growth. A comparative analysis was made with potent H. pylori MTAN (HpMTAN) known inhibitor, 5′-butylthio-DADMe-Immucillin-A (BuT-DADMe-ImmA) and ZINC natural subset database. Optimized ligands from the ZINC natural database were virtually screened using ligand based pharmacophore hypothesis to obtain the most efficient and potent inhibitors for HpMTAN. The screened leads were evaluated for their therapeutic likeness. Furthermore, the ligands that passed the test were subjected for MM-GBSA with MTAN to reveal the essential features that contributes selectivity. The results showed that Van der Waals contributions play a central role in determining the selectivity of MTAN. Molecular dynamics (MD) studies were carried out for 100 ns to assess the stability of ligands in the active site. MD analysis showed that binding of ZINC00490333 with MTAN is stable compared to reference inhibitor molecule BuT-DADMe-ImmA. Among the natural inhibitors screened after various docking procedures ZINC00490333 has highest binding score for HpMTAN (− 13.987). The ZINC inhibitor was successful in reproducing the BuT-DADMe-ImmA interactions with HpMTAN. Hence we suggest that ZINC00490333 compound may represent as a good lead in designing novel potent inhibitors of HpMTAN. This in silico approach indicates the potential of this molecule for advancing a further step in gastric ulcer treatment.

Graphic abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40203-021-00081-2.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Menaquinone, Virtual screening, MMGBSA, Molecular simulation

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a microaerophilic Gram negative bacteria that lives in human gastric habitat and is responsible for 85% of gastric ulcers around the world. Continuous use of antibiotics to eradicate H. pylori has increased the rate of multidrug resistance intensity in them (Scheer et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2012a). This necessitates the need of a potential drug to eradicate the pathogen. Identification of potential drug target is therefore crucial in the step of chemotherapeutics. The bacterial multifunctional enzyme 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-enosyl homocysteine nucleosidase is of paramount importance in the field of drug target as it has significant roles in multiple pathways in bacterial cells (Mishra and Ronning 2012). It belongs to the family of N-ribosyl transferase and functions as a catalyst that is involved in the release of adenine and the ribose-containing products through the irreversible hydrolysis of N-ribosidic bond of four different adenosine-based metabolites (Gutierrez et al. 2007) S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), 5′methylthioadenosine (MTA), 5′-deoxyadenosine (5′-DOA) and 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine (Mishra and Ronning 2012). Further the adenine phosphoribosyl transferase add the end product adenine into the adenine nucleotide pool and thereby involves in adenine recycling (Singh et al. 2005) and another product 5-methylthio-d-ribose is phosphorylated to 5-methylthio-α-d-ribose 1-phosphate and converted into methionine (Myers and Abeles 1989). Bacterial MTAN also plays a key role in various metabolic processes like quorum sensing, methylation reactions, purine salvage, and poly-amine biosynthesis, autoinducer-2 biosynthesis, and menaquinone biosynthesis which in turn are metabolically linked to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and these transformations controls the methylation of proteins, nucleic acids, and complex carbohydrates and involves various lipids also (Evans et al. 2004; Withers et al. 2001). At the same time sequential transfers of the aminopropyl group from decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine forming spermidine and spermine produce MTA as a by-product. Continuous breakdown of MTA is in turn necessary for functioning of spermidine and spermine synthases. This polyamine synthesis is prone to inhibition if MTA accumulation happens (Pajula and Raina 1979). MTAN activity is also linked to important auto inducer I (AI1) and II (AI2) production, which is important quorum-sensing signalling molecule (Parveen and Cornell 2011). Among all these processes menaquinone (Vitamin K2) synthesis is vital for H. pylori survival. It employs an alternative pathway unlike the regular menaquinone synthesis in bacterial system. Hence, inhibition of MTAN leads to inhibition of several vital bacterial mechanisms through the accumulation of toxic by products (Lee et al. 2004) and there by places MTAN as central hub in bacterial system and an attractive candidate for chemotherapeutics.

Menaquinones are lipid soluble molecules and are obligate components of electron transfer during respiration in many pathogenic bacteria. Menaquinone (vitamin K2) acts as electron carriers that shuttles electron between membrane bound molecules during respiration in bacteria (Hiratsuka et al. 2008). In contrast to conventional and classical menaquinone biosynthesis pathway of Gram negative bacteria, H. pylori and Camphylobacter jejuni use an alternative pathway called Futalosine pathway for menaquinone biosynthesis, which make the enzymes involved in this pathway to be selected as potential drug targets (Banco et al. 2016). Moreover humans lack menaquinone synthesis which together add the attractiveness towards selecting MTAN as potential drug target (Wang et al. 2012a). MTAN is absent in Homo sapiens. Instead, 5-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) is the only enzyme capable of metabolizing MTA. To add, in humans menaquinone functions as a cofactor for the post-translational generation of γ-carboxyglutamate residues in proteins that in turn are involved in blood coagulation, bone metabolism, and vascular physiology (Furie et al. 1999). For both classical and alternative pathway of menaquinone biosynthesis, chorismate is the common substrate. However, the alternative pathway branches at chorismate and the nucleoside moiety of inosine joins to give futalosine (6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine) (Seto et al. 2008). Further hydrolysis of 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine at the N-ribosidic bond is catalysed by MTAN to release adenine and dehypoxanthine futalosine finally employing dehypoxanthine futalosine as the precursor of menaquinone synthesis (Wang et al. 2012a).

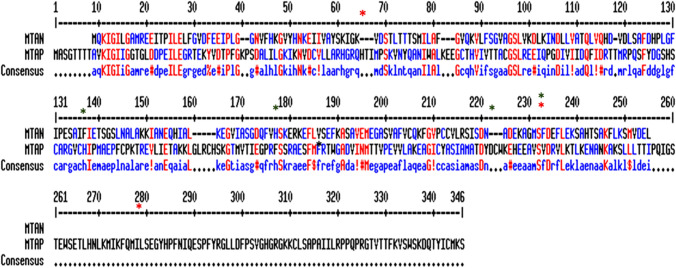

Bacteria-specific inhibitor design requires discrimination against human enzymes that are involved in catalysing similar reactions. Human MTAP and Bacterial MTAN posses three active site regions—the adenine/purine, ribose, and 5′-alkylthio binding sites. Structural superimposition and comparison with nucleosidase specific inhibitors [5′-methylthioadenosine (MTA), and 5′-methylthiotubercidin (MTT)] has revealed substrate specificity of bacterial MTAN due to the changes in the active site architecture and residual difference in binding regions (Appleby et al. 1999). Among the binding sites Alkyl thio binding site of MTAP and MTAN differs mostly. MTAP has highly restricted and unique residues like His65, Val233, Leu237, and Leu279 that forms a cap over the 5′-alkylthio binding pocket. On the other hand MTAN lack these residues and is open to exterior surface (Lee et al. 2004). This specific feature of Alkyl thio binding site of H. pylori MTAN (HpMTAN) make it a prime binding site for ligands to be designed specifically for H. pylori and sparing other commensals (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Active site and sequence comparison between human MTAP (Uniprot ID: Q13126) and HpMTAN (Uniprot ID: Q9ZMY2) done on MultAlin Multiple sequence alignment by Florence Corpet. Red star denotes unique residues at alkyl thio binding of MTAP that are absent in H. pylori. Green star denotes active residues of MTAP that differs from H. pylori binding site residues

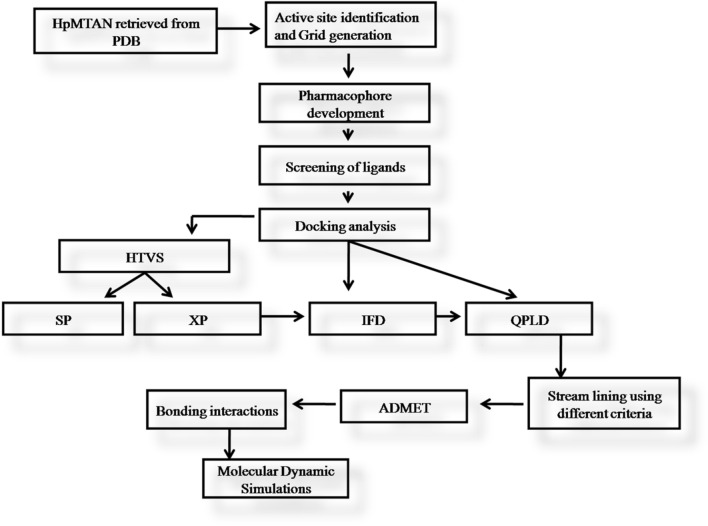

In this study, we have generated ligand based pharmacophore models with immucillin analogues based on ligand based pharmacophore modelling method to analyze the important structural features required for the biological activity of the ligands. Further natural compounds from Zinc Data base were screened virtually and docked into the proposed binding site, to identify the important residues responsible for the receptor-ligand interaction. Further the time-dependent conformational change of the protein–ligand complex was studied using a molecular dynamics simulation study.

Materials and methods

Protein preparation

The X-ray crystallographic structure of HpMTAN with co-crystal ligand with 1.9 Å resolution was retrieved from the protein data bank (PDB 4FFS). The selected protein was prepared individually using the protein preparation wizard workflow of GLIDE (Schrödinger 2017) (Sastry et al. 2013). The steps involved were removing crystallized free water molecules beyond 5 Å distance and RNA, adding hydrogen, adding missing side chains, assigning atom, loop filling. Hydrogen bonds assignment tool was used to optimize the hydrogen bond network by repairing the overlapping hydrogen. Finally impref module optimize the position of hydrogen bonds and kept all the atoms in place (Kataria and Khatkar 2019a). After implementing necessary corrections to the structure, the protein was subsequently minimized using OPLS 2005 force field using heavy atom convergence of 0.3 Å. Finally the protein is pre-processed and minimised through a three step process. During refine step protein and ligand were retrieved and rest of additional buffers and small molecules were deleted. Processed protein–crystal complex was taken for further steps of analysis.

Ligand preparation

ZINC15 provides free database which contains a data of over 12 million commercially available compounds that are categorised into different subsets and represent molecules in ready to dock models (Irwin et al. 2012). Around 10 lakhs ZINC natural product subset database alone was used in the present study. Structural coordinates of compounds were retrieved in mol format. Ligands employed in the study viz. ZINC and decoy molecules were prepared using Ligprep module, Schrödinger 2017 (Mandal and Das 2015). All the subjected ligands were ionized at neutral pH 7 with ionizer and desalt option was activated. Each ligand was assigned with an appropriate bond order and minimized using OPLS 2005 Force field and one low energy conformation for each ligand was generated (Kataria and Khatkar 2019b). The module generated single, low-energy; 3D coordinates with correct chiralities for each input structure. Ionization states for the compounds were generated at pH of 7.0 ± 2.0 with Epik and tautomeric states were generated. A force field of OPLS_2005 was used for the minimization of the compounds. Chiral centres selected to avoid stereioisomer generation by retaining the original states.

Ligand based pharmacophore modelling

Molecular docking

The docking program, was first evaluated for its reliability through re-docking But-DAD-Me-ImmA in the alkyl thio binding site of HpMTAN. It was observed that maestro software has reproduced the binding pose of cocrystal ligand BuT-DADMe-ImmA with a root mean square deviation of 0.19 Å. The result indicated that docking process can generate a reliable conformation for all the ligand molecules. The redocked image is attached as supporting information (Fig. 2). Known inhibitors were subjected for docking procedures. XP and IFD score of known inhibitors tabulated and attached as supporting information (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 2.

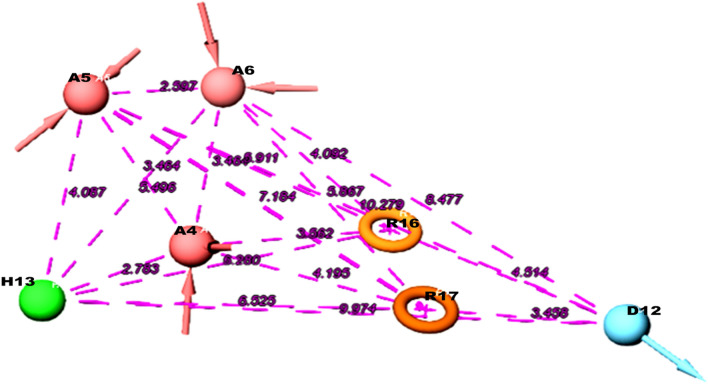

The best pharmacophore hypothesis AAADHRR measurements between features. The red colour symbolise the H-bond acceptors, and green colour indicates hydrophobic regions and blue colour for H-bond donors where the pink dotted lines indicate the distance between the pharmacophore features (Å)

Generation of common pharmacophore HpMTAN hypothesis

A total of 17 potential MTAN inhibitors retrieved from the BRENDA DATABASE and literatures (Harijan et al. 2019; Schomburg et al. 2017). They were used to generate common pharmacophore hypotheses with the help of PHASE module implemented in Schrödinger. Utilizing the built‐in six pharmacophoric features namely hydrogen bond acceptor (A), hydrogen bond donor (D), hydrophobic group (H), negatively charged group (N), positively charged group (P), and aromatic ring R, PHASE screen the ligands for common pharmacophore features. The PHASE module was used for the development of quantitative pharmacophore model. Based on the diversity of chemical structure and IC50 values of these selected inhibitors, a quantitative pharmacophore model was generated. Before initiating the development, conformers were generated for all the 17 ligands. A maximum of 100 conformers were generated per structure by the ConfGen algorithm. During this step hydrogen bonding interactions were suppressed on the view of identifying conformers that bind to receptor residues rather than forming an intra hydrogen bond (Kalva et al. 2013). Ligands with pIC50 value ranging from 3.6 to 8.2 were utilised for generating the pharmacophore model. Active and inactive threshold of pIC50 > 5.0 and < 4.0 were applied for the dataset to yield 9 actives, 5 inactive and 3 moderately active compounds (Kaushik et al. 2018). Further a set of common pharmacophore features for the HpMTAN inhibitors were produced using the PHASE create sites option, which in turn create the site points for each conformer of the input ligands. From the generated phasepharm output file, pharmacophore hypothesis with high survival score were selected for ligand screening. In parallel all the pharmacophores were superimposed with 8 highly active molecules in a terminal box size of 1 Å using an intersite distance of 2 Å. The common pharmacophore hypotheses emerged from phasepharm process were subsequently scored with respect to the inactives using a weight of 1.0. Hypotheses were selected based on the survival active, inactive and fitness score and by setting the root mean square deviation (RMSD) below 1.0, where highest survival score reveals better mapping of the pharmacophore with the active ligand molecules further fitness score confirms the quality of pharmacophore hypothesis (Kalva et al. 2014).

Pharmacophore validation

Enrichment calculation method evaluated the discriminative ability of the generated hypothesis to separate active compounds from inactive compounds. Decoys library was downloaded from Schrödinger suite. This include molecules that posses similar physicochemical properties like molecular weight, hydrogen bond (H‐bond) acceptor, H‐bond donor, ring count, and AlogP but no drug-like properties. These are seeded with selected set of inhibitors to know the actives and avoid false enrichment rate. For this evaluation a database containing 2017 molecules of known actives and inactives were prepared. Among the 2017 molecules 17 molecules were known inhibitors of MTAN enzyme with different mode of activities, while the rest 2000 are decoy molecules that are downloaded from the Schrodinger website. A combination of active molecules seeded with decoy was used to screen with ligand based pharmacophore models to calculate GH scores.

The hypotheses were scored using default parameters set for site score, volume score, selectivity, number of matches and energy terms from the PHASE generated output.

Database screening using ligand based pharmacophore models

Validated hypothesis was taken for compounds to be screened from ZINC database comprising 10 lakhs natural compounds. Screening was done by using PHASE module—ligand and database screening. Ligand based 3D pharmocophore screening was employed for MTAN inhibitors dynamic analysis using PHASE screening (Schrödinger 2017) (Geppert et al. 2010; Khan et al. 2016). Major PHASE screening criteria include (1) the intersite distance matching at 2.0 Å, (2) match at least four features, (3) should not have an inclination for partial matches involving more sites, and (4) gambol conformer generation of structures with more than 15 rotatable bonds.. In the current study pharmacophore model was used to identify the lead structure compound from ZINC natural compound database. From the output file the natural compounds were filtered based on the fitness score.

Virtual screening

Virtual screening aids in screening potential leads against a target. Based on the efficiency of selected ligands to interact with the binding site residues Virtual screening includes a strict selective filtration that contains rigid and flexible docking analysis for prediction of binding analysis and efficiency (Esther et al. 2017; Jang et al. 2018). Virtual screening was carried out by providing active site of the receptor. The in silico protocol for screening virtually comprises three steps: high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS), standard precision (SP), and extra precision (XP). For our study, HTVS and XP docking procedures were applied. Virtual screening work flow includes ligand preparation as one of the steps. Since ligands had been prepared previously this step was skipped. HTVS and XP docking accuracy level was only set for screening the compound databases. The screened molecules were ranked according to G-scores and Glide energy. Empirically based Chem Score function works as the starting point Glide scoring. Favourable hydrophobic, hydrogen-bonding, and metal-ligation interactions, and penalizes steric clashes are recognised by this algorithm. Finally Schrödinger’s proprietary Glide Score scoring function re-score minimized poses.

where a = 0.065, b = 0.130 and vdW denotes Vanderwalls energy, Coul for coulombic energy, Lipo is the lipophilic term, Hbond is the hydrogen bonding term, Metal is the metal binding term, BuryP is penalty for buried polar groups, RotB denotes penalty for freezing rotatable bonds and finally Site is polar interactions in the active site (Ramachandran et al. 2016).

ADMET property analysis

QikProp module aids rational drug search and was used to analyse drug likeliness of the hits (Kalirajan et al. 2019). The ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion) filtration criteria was used to examine and calculate the drug likeliness properties of the hits. Relevant pharmaceutical properties, including human oral absorption, Molecular weight, H-bond acceptors, H-bond donors, QPlogS (aqueous solubility), QPlogPo/W (octanol/water partition coefficient) and QPlogBB (brain blood partition coefficient), QPlogS (aqueous solubility), central nervous system activity, HERG K + channel blockage (logHERG), log Ps (rate of brain penetration), apparent Caco-2 (QPP Caco), MDCK cell per- meability (QppMDCk), Lipinski rule of five violations, and Jorgensen rule of three (Kataria and Khatkar 2019a; Raza et al. 2017). The compounds obtained from pharmacophore screening were selected as input molecules for analyzing the ADME properties.

Induced fit docking (IFD)

Prime tool was employed for IFD. Top hits from visual screening and leads carrying ADMET properties were selected and subjected for induced fit docking (IFD) analysis. Glide and the refinement module in prime accurately predict a receptor’s ligand binding modes and concomitant structural changes. The induced fit protocol begins by docking a ligand with Glide. The tool uses reduced van der Waals radii and an increased Coulomb-vdW cut-off, to generate a diverse ensemble of ligand poses further temporarily remove highly flexible side chains during the docking step. The tool develop closest conformer to the shape and binding mode of ligand molecules. Energy of protein structures and the resulting complexes are ranked according to Glide score. Glide's superior scoring function and Prime's advanced conformational refinement ensure the accuracy.

Molecular dynamics

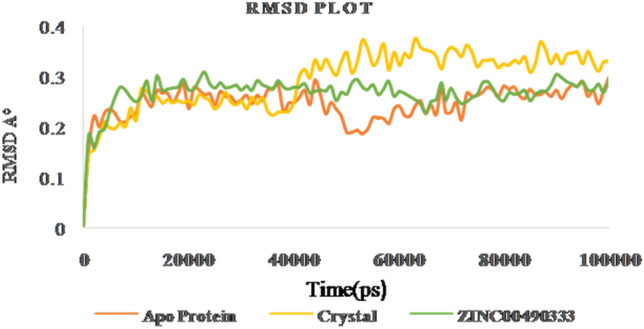

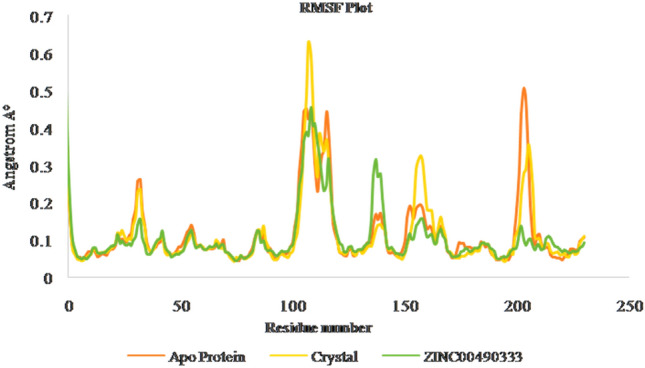

GROMACS (Groningen Machine for Chemical Simulations) package (v. 2016.3) was used to perform all molecular dynamics simulations using GROMOS96 53a6 force field (Oostenbrink et al. 2004) further placed them in a box containing SPC216 water molecules. Chloride ions added to neutralize the net charge of the system to zero once the Periodic boundary conditions were set. Verlet cutoff scheme used for energy minimization iterations. Particle mesh Ewald (PME) algorithm with a cutoff of 1.0 nm employed. After equilibrating the system to the room temperature and pressure, and a simulation of 100 ns was performed for the open MTAN, novel hit and co-crystal ligand complexes. Prepared protein ligand complexes were simulated for 100 ns time period to investigate the stability of the docked ligands. Energy, root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) fluctuations, (radius of gyration) ROG plot, H-bond formation were analyzed for the simulated system with respect to the simulation time (Mandal and Das 2015).

Results and discussion

Screening of potential ligands with ligand based pharmacophore hypothesis

Ligand-based computational method of docking encompasses an efficient similarity measure and a reliable scoring method and also the computational method is able to screen a large number of potential ligands with accuracy and speed (Dai and Guo 2019; Hamza et al. 2012). Ligand based virtual screening for the current study involves the screening of a large collection of small molecules those are structurally similar to the hypothesis generated for the known inhibitors selected from the Zinc database library using the software docking protocols (Monika and Singh 2013). Pharmacophore modeling enables an in-silico screening of library of 3D databases of small molecule compounds to find structures with desired binding activity and selectivity towards HpMTAN active site residues. Common spatial arrangements functional groups that are crucial for a ligand’s biological activity are identified by PHASE (Arora et al. 2019). For the current study a set of six pharmacophore features are developed by PHASE module for the input training and test sets. This include hydrogen bond acceptor (A), hydrogen bond donor (D), hydrophobic group (H), negatively charged group (N), positively charged group (P) and aromatic ring (R). To generate the hypothesis a total of 17 compounds showing good inhibitory activities against bacterial MTAN were collected from BRENDA database and literatures(Evans et al. 2018) (Harijan et al. 2019b). Molecules available with experimental IC50 values were only chosen for the study. For proper and fine screening, repeated molecules and analogues with poor inhibition activities from the database were excluded. Molecules were considered active or inactive based on description studies conducted from literatures. Among the 17, 12 compounds were found active and rest 5 inactive according to BRENDA database and literature references (Schomburg et al. 2017) (Table 1). Among the several chemical inhibitor scaffolds for MTAN, immucillins reported as the best and optimal to bind with transition state of the enzyme. Literature survey reports, BuT-DAD-ME-ImmA with a best inhibition activity (MIC90) of < 8 ng/mL towards MTAN (Wang et al. 2012a). Several femtomolar and picomolar transition state analouge inhibitors of immucilin has been reported with MTAN inhibition (Gutierrez et al. 2009; Singh et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2012). Studies have reported that DADMe-Immucillins of second-generation are closer mimics of highly dissociated N-ribosyl transferase transition states of MTAN. In turn current MTAN inhibitors are adenosine analogs that inhibit human methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP), a homolog of the bacterial MTANs, and exhibit exceptional Kd values (Ronning et al. 2010). However, the work has designed to specifically target the bacterial proteins over the human homolog so adenosine was given as inactive with tree-based partition algorithm, PHASE generated different variants- maximum of seven featured hypothesis and a minimum of four featured pharmacophores. Partitioning technique of module groups the similar pharmacophores features according to their inter site distances. PHASE generated 12 different hypothesis for HpMTAN ranging from four to seven features DHRR, ADHRR, AADDDRR, AAADDRR, ADDDRR, AAADRR, DDDRR, AADHRR, DDDHRR, AAADHRR, AAADHHRR, AADHHRR. Among the generated hypothesis AAADHRR showed highest survival score of 5.595 and an inactive score of 1.680 and therefore was chosen as best hypothesis (Table 2). The pharmacophore features presented in the selected hypothesis included three H-bond acceptors A4, A5and A6, one H-bond donor D12, one hydrophobic H13 and two ring aromatic group R16 and R17 (Fig. 3). The best hypothesis was validated with training and set compounds. Superimposition of Hypothesis with lead ZINC molecules indicated that among the seven features five features mapped perfectly where A4, A5 and A6 acceptor features correctly mapped to the oxo groups, and the hydrogen atom of methylene group in the pentyl ring, the D12 donor feature was mapped to the amino group of purine. The hydrophobic groups H12 feature mapped to the sulpanyl group and the R16 and R17 features mapped to the purine ring group of the ZINC00040150 further, another lead ZINC0049033 had minimum five features mapped, which include ring features 16 and 17 to the purine rings, A4 acceptor at methylene group, D12 donor feature to amino group at purine and H13 mapped to the nuclei of pyridine (Fig. 4) with fitness score of 2.27 and 2.03 respectively.

Table 1.

Data set of inhibitors of HpMTAN used for pharmacophore analysis with experimental and predicted Ic50 analysis

| Serial no. | Compound | Structure | IC50 ( nM) | PIc50 | Commentary on activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Butyl-thio-DADMe-ImmucillinA |

|

6 | 8.22 | Strong |

| 2 | Methyl-thio-DADMe-ImmucillinA |

|

27 | 7.56 | Strong |

| 3 | Ethyl-thio-DADMe-ImmucillinA |

|

31 | 7.50 | Strong |

| 4 | S-8-aza-adenosyl-l-homocystiene |

|

1800 | 5.74 | Strong |

| 5 | 5′-isobutylthio-3-deaza-adenosine |

|

13,000 | 4.9 | Moderate |

| 6 | 5′-Chloroformycin |

|

400 | 6.4 | Strong |

| 7 | 5′-Isobutyl thioinosine |

|

132,000 | 3.9 | Poor |

| 8 | 5′-Methylthioformycin |

|

60 | 7.2 | Strong |

| 9 | 5′-Methylthiotubericidin |

|

7700 | 5.1 | Strong |

| 10 | S-Formycnlhomocystiene |

|

20 | 7.7 | Strong |

| 11 | S-Tubercydinylhomocystiene |

|

3200 | 5.5 | Strong |

| 12 | Sinefungin |

|

24,000 | 4.7 | Moderate |

| 13 | S-Adenosyl l homocystiene sulphoxide |

|

69,000 | 4.1 | Poor |

| 14 | 5-Methyl thio 3-deaza adenosine |

|

79,000 | 4.1 | Poor |

| 15 | n-Butyl thioinosine |

|

94,000 | 4.02 | Poor |

| 16 | Adenine |

|

216,000 | 3.7 | Poor |

| 17 | N6 dimethyl 3- deaza adenosyl l homocystiene |

|

20,000 | 4.7 | Moderate |

Table 2.

Features and properties of hypothesis generated using PHASE module. Best Hypothesis given in bold

| Hypothesis ID | Survival score | Site | Survival inactive | Vector | Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAADHRR | 5.595 | 0.667 | 1.680 | 0.873 | 0.620 |

| DDHRR | 5.002 | 0.367 | 1.895 | 0.911 | 0.609 |

| ADHRR | 5.000 | 0.670 | 2.063 | 0.945 | 0.686 |

| AADHRR | 5.184 | 0.672 | 1.905 | 0.883 | 0.608 |

| AADHHR | 5.232 | 0.535 | 1.680 | 0.983 | 0.709 |

| DDDHRR | 5.343 | 0.654 | 1.595 | 0.766 | 0.615 |

Fig. 3.

Pharmacophore mapping of the lead ZINC compounds on the hypothesis AAADHRR, a ZINC00490333 with fitness score of 2.03 and b ZINC00040150 with fitness score 2.27

Fig. 4.

Hypothesis validation a enrichment analysis of hypothesis model. b Receiver operating curve. Enrichment analysis graph indicating validation of hypothesis in screening active ligands of dataset. Receiver operating curve area under curve indicates screening analysis was fair enough to screen out true active ligands from the false decoy inactive molecules seeded

Pharmacophore model validation

Pharmacophore models generated were then evaluated using the Boltzmann‐enhanced methods. Enrichment result from screening revealed that the generated pharmacophore model was successful in retrieving 80% of active compounds from the provided database. The hypothesis generated with PHASE module was validated with the decoy molecules and further enrichment assay to separate the false positive and negative (Arora et al. 2019). EF% (enrichment factor) is used to measure the enrichment for early recognition of known actives from the randomly distributed decoys listed within the defined internal library. AAADHHR recognized the actives 38, 43.8, 44, 56 and 81% for 1, 2, 5 10 20% respectively of total hits that represent the effective identification of the actives from the decoy ones. The enrichment screening was successful for MTAN as the EF score was 37% revealing that the created model is good enough for discriminating known actives from the inactive molecules and also suitable for retrieving active inhibitors. The curve clearly shows the descrimination of active by the generated pharmacopore model. Further the reciever operating curve (ROC) area shows model was good enough to descriminate true and false posituve ligands from binding and filtered 80% of true positive ligands from the active and inactive decoy list (Fig. 5). The plausible score value for ROC curve to be efficient and suitable must be greater than or equal to 0.7 and further if score seems to closer to 1.0, that in turn indicates a better hypothesis. AAADHRR hypothesis for the current study shows an ROC score of 0.87, confirming the efficiency of hypothesis in screening out actives. The ROC plot of AAADHRR reveald an area under accumlation of 0.87 indicating a suitable ROC score to separate actives from inactives. Area under the accumulation curves (AUACs) ranks the probability of finding the actives before the relative rank. The value of AUAC for the hypothesis AAADHRR is 0.87 indicating that the hypothesis can find the actives before the relative rank. Plausible value for AUAC lies between 0 and 1.

Fig. 5.

Hydrophobic and H-bond interactions by top lead Zinc molecules with HpMTAN. a–e ZINC lead compounds ZINC00490333, ZINC0040150, ZINC15377615, ZINC14318066 respectively

Another hypothesis ranking method in Enrichment analysis includes BEDROC where the metric identifies the actives with the concept of early recognition. For this BEDROC metric was set to α = 20.0, which entails the first 8% of the ordered list contributes to 80% of the maximum contribution to the BEDROC. The score of BEDROC for AAADHRR is 0.48. In the view of identifying the performance and ranks the actives, robust initial enhancement (RIE) metric is employed. Higher positive value of RIE indicates better screening performance. The value of RIE is 8.67 showing that AAADHRR can screen the compounds with better performance since a higher positive value of RIE denotes and indicate better screening performance. The value of Eff is 0.948 at 1% of enrichment factors with respect to N% sample size, which proves that AAADHRR has the best capability to distinguish the actives from inactive. Where Eff denotes enrichment factor efficiency that distinguish actives from decoy molecules. Acceptable Eff value ranges between 0 to 1. Value towards 1 denotes efficient distinguish of actives and Eff towards 0 indicates recovery of active and decoy with equal proportional rate (Nayak et al. 2019).

Plausible enrichment values of the hypothesis AAADHRR elucidate its strong predictive power to identify active ligands with high performance. The validated pharmacophore hypothesis AAADHHR was used for virtual screening against ZINC databases.

Screening of natural inhibitors

PHASE screen module screened the compounds from ZINC (database having 10 lakhs clean drug like compounds) databases to generate the library against HpMTAN alky-thio binding site. A total of 367,800 were screened by the hypothesis with matching features. A minimum of 25% matching was provided as criteria during screening analysis of PHASE. Compounds with scoring > 1.8 were taken for further docking analysis. Since score below this value posses poor matching with pharmacophore features selected. This included 124,786 compounds. As per the standard protocol, to narrow down the compounds with AAADHRR hypothesis features, the screening begins with different scoring system which includes HTVS and followed by SP and XP. After the completion of every screening stage, certain percentage of screened lead compounds employed as the input to the next scoring schemes. In this study, 50% of the best conformational states are screened by HTVS which are fed as the input for SP docking and leads from 30% of the output from SP were provided to the XP scoring scheme. In XP protocol, 10% of input compounds are filtered out and are ranked based on the highest docking score (GLIDE score) (Table 3). Leads with Glide score > − 11.5 kcal/mol was subjected for induced fit docking (IFD). Top leads from IFD output included ZINC00490333, ZINC14138066 and ZINC15377615 with score values of − 13.987 kcal/mol, − 13.801 kcal/mol and − 12.747 kcal/mol respectively. QPLD was done to cross check the docking scores with IFD scores. Interestingly scores were similar indicating that docking was successful in reproducing the ligand poses (Table 4).

Table 3.

Docking scores, energy, e-model scoring and fitness score with AAADHRR hypothesis of visually screened lead zinc natural subsets together with reference molecule (PDB ID.4FFS). Reference molecule and hit Zinc00490333 scores given in bold

| Compound | Structure | Glide score | Glide energy | Glide-e model | Fitness score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC/PDB | ZINC/PDB | XP | SP | XP | SP | XP | SP | AAADHRR |

| 4FFS |

|

− 14.128 | − 13.451 | − 82.231 | − 80.655 | − 81.651 | − 81.224 | 3.00 |

| ZINC00490333 |

|

− 13.650 | 13.315 | − 72.762 | − 71.886 | − 70.584 | − 70.201 | 2.03 |

| ZINC14138066 |

|

− 13.257 | − 12.974 | − 70.675 | − 67.824 | − 53.665 | − 50.744 | 1.97 |

| ZINC05594584 |

|

− 13.087 | − 13.075 | − 55.621 | − 52.642 | − 69.365 | − 62.899 | 1.97 |

| ZINC15376886 |

|

− 12.350 | − 12.339 | − 75.566 | − 73.286 | − 52.371 | − 52.120 | 1.94 |

| ZINC00040150 |

|

− 11.857 | − 11.786 | − 62.344 | − 60.526 | − 67.249 | − 67.002 | 2.27 |

| ZINC15377615 |

|

− 11.877 | − 11.835 | − 66.343 | − 64.594 | − 60.681 | − 58.772 | 1.88 |

| ZINC06575298 |

|

− 10.688 | − 10.080 | − 65.010 | − 64.908 | − 82.070 | − 81.225 | 1.9 |

Table 4.

The IFD Glide score and QPLD in kcal/mol score of leads and reference molecule (PDB ID: 4FFS) from IFD. Scores of reference molecule and hit ZINC00490333 given in bold

| ZINC subset | Glide G score | IFD score | Qpld |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00490333 | − 13.987 | − 483.84 | − 13.225 |

| 14138066 | − 13.801 | − 501.97 | − 13.203 |

| 15377615 | − 12.747 | − 501.49 | − 12.524 |

| 00040150 | − 12.359 | − 483.14 | − 12.066 |

| 15376886 | − 12.220 | − 499.75 | 11.141 |

| 4FFS | − 16.307 | − 506.168 | − 16.898 |

ADME analysis

The ADMET properties for the 5 lead ZINC ligands were predicted in-silico by utilizing qikprop module of Schrödinger suite. Molecular weight of the compounds are in the range of 222.292–246.314. Evaluated number of hydrogen bond donors by the solute to water atoms in the fluid arrangement of complex were in the range of 2–4. Vice versa evaluated number of hydrogen bonds acceptors acknowledged by the solute from water particles in the fluid arrangement of the complex are in the range of 5.2–7.7. The compound ZINC00490333 has the most elevated Lipophilicity QplogPo/w value of 0.558. Lipophilicity is another crucial physicochemical property of a drug molecule which determines its pharmacology efficacy and solubility towards lipid, absorption and penetration of membranes, solubility and binding of plasma proteins. Hit compound Zinc00490333 possess a possibility to cross the blood–brain barrier (QP log BB for brain/blood) of 0.240 (recommended value range is − 3.0/1.2), Cell permeability (QPPCaco) of 178.838 and Human Oral Absorption of 71% (< 25% is poor) with medium quality (> 80 high). The results of in silico ADMET screening showed that the compound ZINC00490333 posses best pharmacokinetic properties to be considered as a drug molecule (Table 5).

Table 5.

ADMET property analysis of lead ZINC ligand and reference molecule with (PDB ID:4FFS). Scores of Hit ZINC00490333 and reference molecule in bold

| Zinc natural ligands | MW 130.0/725 |

MV 500.0/2000.0 |

HBD 0.0/6.0 |

HBA 2/20 |

Qplog Po/W − 2.0/6.5 |

QPP Caco < 25P/> 500G |

QP logS − 6.5/0.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC00490333 | 246.314 | 797.018 | 2.000 | 6.000 | 0.558 | 178.838 | − 0.891 |

| ZINC00040150 | 235.245 | 755.982 | 3.000 | 6.000 | − 0.084 | 235.070 | − 2.259 |

| ZINC15377615 | 236.319 | 805.625 | 4.000 | 6.000 | − 0.169 | 52.133 | − 1.121 |

| ZINC14138066 | 238.292 | 792.910 | 4.000 | 7.700 | − 0.925 | 54.215 | − 0.736 |

| ZINC15376886 | 222.292 | 688.456 | 3.000 | 5.200 | 0.404 | 299.207 | − 2.209 |

| 4FFS | 335.468 | 1121.17 | 4 | 6.7 | 1.64 | 63.475 | − 2.648 |

MW—130.0/725, MV—500.0/2000.0, HBD—0.0/6.0, HBA-2/20, Qplog Po/W—2.0/6.5, QPP Caco—< 25P/> 500G, QPlogS—− 6.5/0.5

Binding mode analysis in the dimer interface of HpMTAN

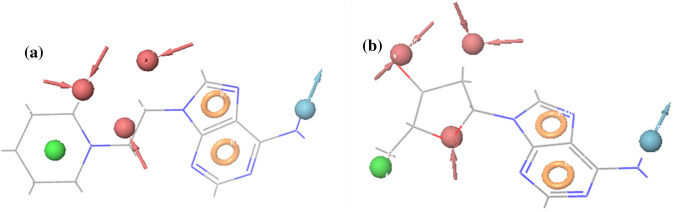

A lock and key model system for substrate binding is allowed by MTAN since solvent interactions at active site and binding pocket bonds with residues stay conserved (Siu et al. 2011). Transition-state or nucleoside analogues that interact with ribosyl and adenyl binding pockets residues within the active site are the tightest binding MTAN inhibitors (Longshaw et al. 2010). H-bond and hydrophobic interaction of lead zinc compound during docking procedures with HpMTAN revealed that they are strong enough to bind with the dimer interface binding region active residues of HpMTAN. The H-bond and hydrophobic interactions made by lead molecules from output has been tabulated. (Table 4). ZINC00490333 shows strong hydrophobic interactions with the dimer interface residues like Phe153, Val154, Ala9, Met10, Ile52, Val172, Phe208, Ala79 and Val78. Further compound ZINC00490333 has hydrogen bond interaction with Asp198 and Val154 through the amine group (H bond donor). A stable π–π interaction, expressing the electron to nuclei is present between aromatic ring of Phe153 and the rings from the purine group of ligand. Further ZINC0049033 was also successful in making a salt brige with Glu173 and Glu13. A reference docking was made with structural complex (PDB ID: 4FFS) to compare the residues during docking procedures. From the result, interestingly both BuT-DAD-me-ImmA and ZINC00490333 bound compound complex exhibit same binding affinity with similar residues. BuT-DADMe-ImmA makes hydrogen bond with Val154, Asp198, Glu13, Glu175 and also a salt bridge with Glu175 and Glu13 further surround by Gly53 and Gly205. The adenyl moiety of ZINC lead produces specific interaction towards active site residues. Another interaction between ZINC lead and reference molecule with HpMTAN include water mediated hydrogen bond between residues like Glu13, Glu175, Arg194, Gly53, Val78 and Met174. But BuT- DadMe-ImmA lack a π–π stalking interaction at adenyl moiety which was present in the ZINC00490333 (Fig. 4). Structural comparison of both inhibitors shows that adenyl moieties bind in the same location but possess slightly different orientations, resulted from differences in the 5′-homocystiene and pyrolidine moiety of Immucillin which was absent in ZINC00490333. Also suggesting that other interactions are predominating and forcing an alternative inhibitor conformation in BuT-DADMe-ImmA (Table 6, Fig. 6).

Table 6.

H-bond and hydrophobic interactions of zinc leads with HpMTAN. Interaction of hit ZINC00490333 in bold

| Compound ID | Hydrophoic contacts | H-bond—residue | Atoms in H bond (ligand-receptor) | Length in angstrome | Glide score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC00490333 | Ala9, Met10, Phe208, Ile52, Met174, Val172, Phe153, Val154, Ala200, Ala79, Val78 | H–O–H Asp198 | H18-OD2 | 2.86 | − 13.987 |

| H–O-H Val154 | H19-O | 2.87 | |||

| H–N–H Val154 | N1–H | 3.12 | |||

| ZINC14138066 | Ala9, Met10, Ile52, Val78, Ala79, Ala200, Ala204, Phe153, Val172, Met174, phe208 | H–O–H (Asp198) | H16–OD2 | 2.69 | − 13.801 |

| H–O–H(Asp198) | H15–O | 2.90 | |||

| H–N–H(Val154) | N3–H | 3.16 | |||

| ZINC00040150 | Ile52, Met10, Ala9, Met174, Val172, Ala200, Ala204, Val154, Phe153, Phe208, Ala79, Val78 | H–N–Hval154 | N4–H | 3.07 | − 12.359 |

| H–O–H asp198 | H12–O | 3.8 | |||

| H–O–Hval154 | H11–OD2 | 3.11 | |||

|

Pi–Pi (phe153) Pi–Pi (Phe208) |

98/ | ||||

| ZINC15377615 | Ile52, Met10, Ala9, Met174, Val172, Ala200, Ala204, Val154, Phe153, Phe208, Ala79, Val78, Leu212 | H–O–H Val154 | H17–O | 2.75 | − 12.747 |

| H–N–Hval154 | N3–H | ||||

| H–O–H asp198 | H16–O | 2.71 | |||

| H–O–HGlu173 | H14–O | 3.04 | |||

| Pi–Pi (Phe153) | |||||

| ZINC15376886 | Ile52, Met10, Ala9, Met174, Val172, Ala200, Ala204, Val154, Phe153, Phe208, Ala79, Val78, Leu212 | H–O–Hasp198 | H16–D1 | 2.7 | − 12.220 |

| H–N–Hval154 | N3–O | 2.90 | |||

| H–O–H Val154 | H15–O | 2.75 | |||

| H–N–HGlu173 | H18–O | 3.13 | |||

| Pi–Pi (Phe153) |

Fig. 6.

Surface binding image of receptor and ligand. a Zinc00490333 with HpMTAN. b BuT-DADMe-ImmA with HpMTAN

MMGBSA

The binding free energies values and their energy components were predicted for the ZINC0049033 and reference ligand BuT-DADMe-ImmA with HpMTAN using Prime MM-GBSA method. The binding energy of ligand ranges from − 60.502 to − 61.613 kcal/mol. Highest binding free energy is crucial parameter for determining the ligand selectivity. Contribution of components like Van der Waals (vdW), lipophilic (Lipo), Coulomb, covalent and solvation was compared for ZINC00490333 and BuT-DADMe-ImmA with HpMTAN to reveal crucial factors that contribute to ligand selectivity. Among the components, Van der Waals (vdW), coulomb, Polar solvation and covalent interactions displayed favorable interactions, whereas, lipophelic interactions displayed non favourable interactions for HpMTAN. ΔGbind is the mixture of different kind of energies which is the final output obtained from the above process. Polar and non-polar energies contribute separately for the generation of ΔGbind. On the current study we examined the ΔGbind for ligands ZINC00490333 the hit and the reference ligand BuT-DADMe-ImmA with receptor HpMTAN. Earlier studies report that ΔvdW (Van der Walls interaction) contribution is the main component in determining the ligand selectivity. ΔvdW interactions were, − 49.88 for ZINC00490333 and − 51.91 for reference ligand respectively. On considering other interactions, the coloumbic interactions of Zinc00490333 and BuT-DADMe-ImmA with MTAN is − 70.50 and − 69.86 respectively, where the ZINC ligand has shown better interaction over immucilin. Further both ZINC0049033 3and Immucillin showed moderate lipophilic scores for MTAN because it has larger and deep alkyl thio binding pockets with major hydrophobic residues. ∆Glipo for ZINC00490333 is − 15.57 and for Immucilin is − 14.82. This indicates that lipophilic contribution of ZINC compound are not crucial for MTAN selectivity. Polar solvation energy revealed ZINC00490333 with an entropy of 77.89 and BuT-DAD-Me-ImmA of 86.18 kcal/mol. A positive polar salvation energy is a good interaction whereas a negative value indicates an exothermic reaction. Moreover, ranking of predicted binding free energies was favourable and in good agreement with screening and docking analysis. This encompass that the docking programs are accurate enough to score the ligands.

Surface analysis of binding pockets with ligands reveals that both the reference inhibitor BuT-DADMe-ImmA and ZINC0049033 have bound perfectly in the binding pocket of HpMTAN. Relatively larger binding pockets are present in bacterial MTAN compared to human MTAN for accommodating alkyl thio inhibitors with large 5′ homocystiene subgroups. This encompasses an important feature that discriminates human MTAP from bacterial MTAN interestingly; the BuT-DADMe-ImmA employed for reference molecule was not properly submerged in the pocket in which solvent exposure was high. This steric hindrance might be due to the presence of sulphur group and large homocystiene moiety in the reference ligandc (Mishra and Ronning 2012). In contrast the ZINC00490333 was perfectly bound to the pocket with minimal solvent exposure, moreover it lacks the homocystiene moety and sulphur atoms but adenyl moiety. ZINC compound lacks 5-pyrolidine and homocystiene moiety. But the cyclohexane amine in the ZINC0049033 produced a stable H-bond with Glu175. The lack of long and bulky tail region might be the reason for the minimum exposure of ligand to the surface and preventing nucleophelic attack. These features again prove that the ZINC 00490333 could act a functional inhibitor for HpMTAN (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

RMSD of apo protein, crystal ligand (4FFS) and ZINC00490333 bound HpMTAN complexes

Molecular dynamic simulation studies

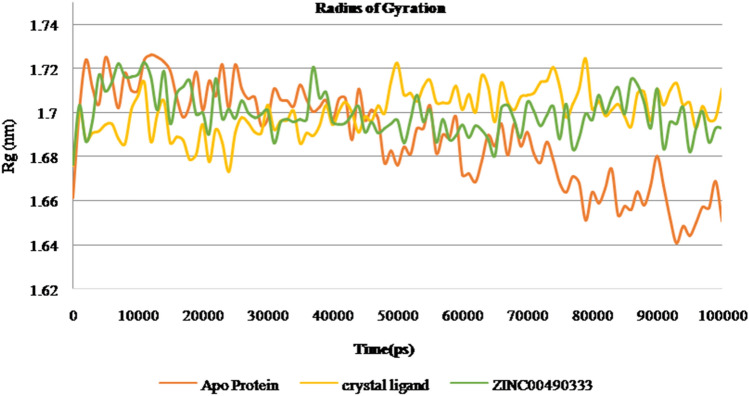

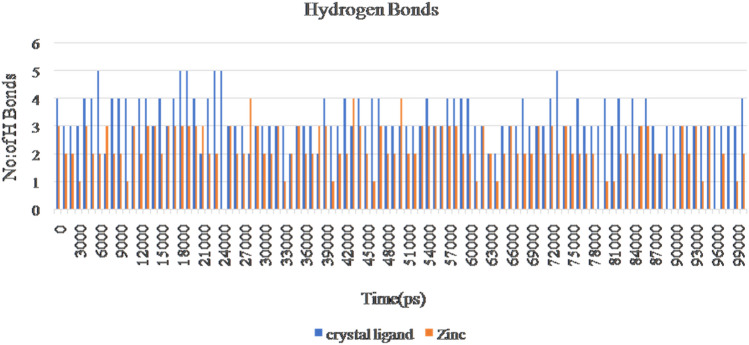

Gromacs software evaluates the stability and conformational distributions changes of respective ligands in the binding pocket of receptor. MD simulations were analysed for apoprotein, protein-known ligand and protein-novel zinc complexes. Stability of all the listed complexes was evaluated under 100 ns of dynamics condition. The lead zinc bound MTAN complex derived from QPLD docking was simulated for 100 ns time period. During simulation, the RMSD of the backbone atoms systemically increased for all the three complexes like Apo, Crystal complex (PDB ID: 4FFS) and ZINC00490333 bound HpMTAN. RMSD of apo protein increased gradually with a maximum RMSD below 0.28 Å. Most of the fluctuations had deviation below 3 Å. However, overall RMSD of apo protein was below 0.3 Å. MTAN crystal maintained a steady confirmation throughout the simulation except at 40000 ps. It had a deviation of 0.31 Å at 42,000 and further increased up to 0.37 Å at 52,000 ps. Whereas a steady confirmation was found with ZINC00490333 bound complex. The stability of novel complex during the simulation was better than the crystal complex employed where former had an overall RMSD of below 0.32 Å. This analysis clearly indicates ZINC00490333 maintained constant RMSD during the simulation (Fig. 8). Relative flexibility of the receptor HpMTAN in presence of inhibitor was studied by RMSF analysis. The results of RMSF analysis indicated that in apo protein, crystal complex and ZINC00490333, significant conformations were centred on the residues 29–32, 105–119, 135–140, 157–164 and 201–210. When compared to apo-protein and crystal complexes, confirmations of ZINC00490333 bound MTAN was steady and had a maximum conformational deviation of 0.45 Å. Fewer confirmations were found at ligand binding regions including Asp198, Val154 Phe153which were involved in forming hydrogen bond confirmation with ZINC ligand. Regions with high confirmations are corresponded to the loops in surface exposed region of receptor (Fig. 9). Radius of gyration (Rg), which is the measure of distance from the axis of rotation, was measured over the period of 100 ns. On analyzing the Rg plot, we have deciphered that the Rg of the apo HpMTAN protein was 1.72–1.66. Whereas of Crystal ligand and ZINC0049033 bound complexes had average Rg of 1.7 nm. This was found steady throughout the simulation (Fig. 10). The binding affinity of the protein is based on the steady formation of H bonds during the whole scale of production MD run trajectories. The number of hydrogen bonds formed between the residues of protein and the compounds over the simulation time is crucial so that, it could reinforce the activity of the agonists. HpMTAN residues at alkyl thio binding site were forming H bonds with bound ligands and we discerned it to be conserved and properly maintained over the course of the simulation time. ZINC0049033 complex found to form a maximum of 4 and an average of 3 hydrogen bounds all over the simulation time (Fig. 11).

Fig. 8.

RMSF of apo, crystal and ZINC00490333 bound HpMTAN complexes

Fig. 9.

Radius of gyration plot of apo protein, crystal ligand (4FFS) and ZINC00490333 bound HpMTAN

Fig. 10.

H-Bond graph of crystal ligand (4FFS) and ZINC00490333 bound HpMTAN complexes

Fig. 11.

Work flow

We have used ligand based pharmacophores to screen natural Zinc databases. Hits based on fitness score were used in docking studies with three different scoring combinations, including Glide SP and XP scores, IFD, QPLD and Qikprop, to predict drug-likeness properties making them likely to be of useful drugs. To validate the docking results, ROC plot and enrichment analysis were employed. Further our results found that leads, including ZINC14138066, ZINC15377615, ZINC00490333, ZINC00040150, ZINC15376886 were successful in nearly reproducing the H-bond interactions formed by BuT-DAD-Me-ImmA. Most of these lead ZINC inhibitors formed strong hydrophobic interactions with highly selective binding site amino acid residues, Leu212, Phe208, Val172, Met174, Phe153, Val154, Ala200, Ala204, Ala79, Val78, Ala9 and Met10 which are directly involved in selectively inhibiting HPMTAN.

Conclusions

In this study, we used a ligand-based pharmacophore docking methods and Molecular dynamics simulation analysis to discover novel HpMTAN inhibitors through a series of virtual screening. These pharmacophore models were used to screen ZINC natural databases to obtain novel leads, which were further refined using docking studies. The identified hits were further validated by comparing the different scoring functions and ROC curves. ZINC0049033 was the best hit for alkythio binding site of HpMTAN. Our results also decipher the importance of Van der Walls interaction and Coloumbic interactions of ZINC lead with HpMTAN active residues. Further identification of stability and energy perspectives via molecular dynamics simulation assay provide guidance for natural inhibitor design of HpMTAN. Careful analysis of molecular dynamics study for 100 ns revealed the stability and thermodynamics of lead ZINC00490333 molecule with HpMTAN. The results of RMSD, RMSF, ROG and H-bond analysis were carefully studied. Stable hydrogen bonds and sufficient hydrophobic interaction with the binding site core residues Asp198, Glu135, Val154 has made the binding of Inhibitor stronger moreover the presence of π–π interactions have added to the stability of Zinc00490333. Further, this research could be potentially benefit in identifying natural inhibitors for HpMTAN and could be taken for further expansion in chemical space for identifying natural MTAN inhibitors. The biological activity assay of lead ZINC molecule is underway and will be reported elsewhere.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors deeply express our sincere thanks to Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, India for their support and constant encouragement which makes this venture a success.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable for the section.

Consent for publication

Not applicable for the section.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Divya S. Raj, Email: sdivyaraj@gmail.com

Chidhambara Priya Dharshini Kottaisamy, Email: k.c.priyadharshini@gmail.com.

Waheetha Hopper, Email: waheetahop@yahoo.com.

Umamaheswari Sankaran, Email: umamsu@gmail.com.

References

- Appleby TC, Erion MD, Ealick SE. The structure of human 5′-deoxy-5′-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase at 1.7 A resolution provides insights into substrate binding and catalysis. Structure (London, England: 1993) 1999;7:629–641. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora R, Issar U, Kakkar R. Identification of novel urease inhibitors: pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening and molecular docking studies. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019;37:4312–4326. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1546620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banco MT, Mishra V, Ostermann A, Schrader TE, Evans GB, Kovalevsky A, Ronning DR. Neutron structures of the Helicobacter pylori 5′-methylthioadenosine nucleosidase highlight proton sharing and protonation states. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:13756–13761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609718113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W, Guo D. A ligand-based virtual screening method using direct quantification of generalization ability. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2019;24:2414. doi: 10.3390/molecules24132414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esther M, Vijayakumar S, Kumar A, Subramanian M, Manogar P. Molecular docking ADMET analysis and dynamics approach to potent natural inhibitors against sex hormone binding globulin in male infertility. Pharmacogn J. 2017;9:s35–s43. doi: 10.5530/pj.2017.6s.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Schramm VL, Singh V, Tyler PC. Targeting the polyamine pathway with transition-state analogue inhibitors of 5′-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3275–3281. doi: 10.1021/jm0306475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GB, Tyler PC, Schramm VL. Immucillins in infectious diseases. ACS Infect Dis. 2018;4:107–117. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furie B, Bouchard BA, Furie BC. Vitamin K-dependent biosynthesis of gamma-carboxyglutamic acid. Blood. 1999;93:1798–1808. doi: 10.1182/blood.V93.6.1798.406k22_1798_1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert H, Vogt M, Bajorath J. Current trends in ligand-based virtual screening: molecular representations, data mining methods, new application areas, and performance evaluation. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:205–216. doi: 10.1021/ci900419k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez JA, et al. Picomolar inhibitors as transition-state probes of 5′-methylthioadenosine nucleosidases. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:725–734. doi: 10.1021/cb700166z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez JA, Crowder T, Rinaldo-Matthis A, Ho M-C, Almo SC, Schramm VL. Transition state analogs of 5′-methylthioadenosine nucleosidase disrupt quorum sensing. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:251–257. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza A, Wei NN, Zhan CG. Ligand-based virtual screening approach using a new scoring function. J Chem Inf Model. 2012;52:963–974. doi: 10.1021/ci200617d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harijan RK, et al. Selective inhibitors of Helicobacter pylori methylthioadenosine nucleosidase and human methylthioadenosine phosphorylase. J Med Chem. 2019;62:3286–3296. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsuka T, Furihata K, Ishikawa J, Yamashita H, Itoh N, Seto H, Dairi T. An alternative menaquinone biosynthetic pathway operating in microorganisms. Science. 2008;321:1670. doi: 10.1126/science.1160446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin JJ, Sterling T, Mysinger MM, Bolstad ES, Coleman RG. ZINC: a free tool to discover chemistry for biology. J Chem Inf Model. 2012;52:1757–1768. doi: 10.1021/ci3001277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang C, et al. Identification of novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitors designed by pharmacophore-based virtual screening, molecular docking and bioassay. Sci Rep. 2018;8:14921. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33354-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalirajan R, Pandiselvi A, Gowramma B, Balachandran P. In-silico design, ADMET screening, MM-GBSA binding free energy of some novel isoxazole substituted 9-anilinoacridines as her2 inhibitors targeting breast cancer. Curr Drug Res Rev. 2019;11:118–128. doi: 10.2174/2589977511666190912154817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalva S, Saranyah K, Suganya PR, Nisha M, Saleena LM. Potent inhibitors precise to S1′ loop of MMP-13, a crucial target for osteoarthritis. J Mol Gr Model. 2013;44:297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalva S, Azhagiya Singam ER, Rajapandian V, Saleena LM, Subramanian V. Discovery of potent inhibitor for matrix metalloproteinase-9 by pharmacophore based modeling and dynamics simulation studies. J Mol Gr Model. 2014;49:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataria R, Khatkar A. In-silico design, synthesis, ADMET studies and biological evaluation of novel derivatives of chlorogenic acid against urease protein and H. pylori bacterium. BMC Chem. 2019;13:41. doi: 10.1186/s13065-019-0556-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataria R, Khatkar A. Molecular docking, synthesis, kinetics study, structure-activity relationship and ADMET analysis of morin analogous as Helicobacter pylori urease inhibitors. BMC Chem. 2019;13:45. doi: 10.1186/s13065-019-0562-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik AC, Kumar S, Wei DQ, Sahi S. Structure based virtual screening studies to identify novel potential compounds for GPR142 and their relative dynamic analysis for study of type 2 diabetes. Front Chem. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MF, Verma G, Akhtar W, Shaquiquzzaman M, Akhter M, Rizvi M, Alam M. Pharmacophore modeling, 3D-QSAR, docking study and ADME prediction of acyl 1,3,4-thiadiazole amides and sulfonamides as antitubulin agents. Arab J Chem. 2016;12:5000–5018. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Settembre EC, Cornell KA, Riscoe MK, Sufrin JR, Ealick SE, Howell PL. Structural comparison of MTA phosphorylase and MTA/AdoHcy nucleosidase explains substrate preferences and identifies regions exploitable for inhibitor design. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5159–5169. doi: 10.1021/bi035492h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longshaw AI, Adanitsch F, Gutierrez JA, Evans GB, Tyler PC, Schramm VL. Design and synthesis of potent "sulfur-free" transition state analogue inhibitors of 5′-methylthioadenosine nucleosidase and 5′-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6730–6746. doi: 10.1021/jm100898v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal RS, Das S. In silico approach towards identification of potential inhibitors of Helicobacter pylori DapE. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2015;33:1460–1473. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2014.954272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra V, Ronning DR. Crystal structures of the Helicobacter pylori MTAN enzyme reveal specific interactions between S-adenosylhomocysteine and the 5′-alkylthio binding subsite. Biochemistry. 2012;51:9763–9772. doi: 10.1021/bi301221k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monika KJ, Singh K. Virtual screening using the ligand ZINC database for novel lipoxygenase-3 inhibitors. Bioinformation. 2013;9:583–587. doi: 10.6026/97320630009583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers RW, Abeles RH. Conversion of 5-S-ethyl-5-thio-d-ribose to ethionine in Klebsiella pneumonia. Basis for the selective toxicity of 5-S-ethyl-5-thio-d-ribose. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10547–10551. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)81656-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak C, Chandra I, Singh SK. An in silico pharmacological approach toward the discovery of potent inhibitors to combat drug resistance HIV-1 protease variants. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:9063–9081. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostenbrink C, Villa A, Mark AE, van Gunsteren WF. A biomolecular force field based on the free enthalpy of hydration and solvation: the GROMOS force-field parameter sets 53A5 and 53A6. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1656–1676. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajula RL, Raina A. Methylthioadenosine, a potent inhibitor of spermine synthase from bovine brain. FEBS Lett. 1979;99:343–345. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80988-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen N, Cornell KA. Methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase, a critical enzyme for bacterial metabolism. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:7–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran B, Kesavan S, Rajkumar T. Molecular modeling and docking of small molecule inhibitors against NEK2. Bioinformation. 2016;12:62–68. doi: 10.6026/97320630012062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza H, et al. Isolation, characterization, and in silico, in vitro and in vivo antiulcer studies of isoimperatorin crystallized from Ostericum koreanum. Pharm Biol. 2017;55:218–226. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2016.1257641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronning DR, Iacopelli NM, Mishra V. Enzyme-ligand interactions that drive active site rearrangements in the Helicobacter pylori 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase. Protein Sci Publ Protein Soc. 2010;19:2498–2510. doi: 10.1002/pro.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry GM, Adzhigirey M, Day T, Annabhimoju R, Sherman W. Protein and ligand preparation: parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J Comput Aided Mol Design. 2013;27:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s10822-013-9644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer M, et al. BRENDA, the enzyme information system in 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;39:D670–D676. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomburg I, Jeske L, Ulbrich M, Placzek S, Chang A, Schomburg D. The BRENDA enzyme information system—from a database to an expert system. J Biotechnol. 2017;261:194–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto H, Jinnai Y, Hiratsuka T, Fukawa M, Furihata K, Itoh N, Dairi T. Studies on a new biosynthetic pathway for menaquinone. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5614–5615. doi: 10.1021/ja710207s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V, et al. Femtomolar transition state analogue inhibitors of 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18265–18273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu KK, et al. Mechanism of substrate specificity in 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidases. J Struct Biol. 2011;173:86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, et al. A picomolar transition state analogue inhibitor of MTAN as a specific antibiotic for Helicobacter pylori. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6892–6894. doi: 10.1021/bi3009664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers H, Swift S, Williams P. Quorum sensing as an integral component of gene regulatory networks in Gram-negative bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:186–193. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.