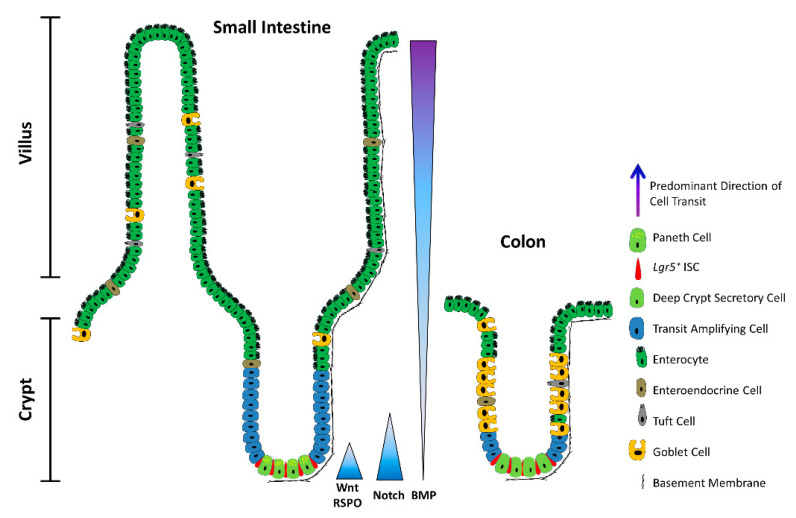

Figure 1.

The architecture of the small intestine and the colon. Schematic depicting a longitudinal section of the intestinal mucosa. The mucosa of the small intestine extends finger-like projections (villi) into the gut lumen, which provide an increased surface area for optimal nutrient absorption. The villi are populated by mature, differentiated absorptive and secretory cell types, including absorptive enterocytes, hormone- and neurotransmitter-secreting enteroendocrine cells, mucus-secreting goblet cells, tuft cells, and microfold (M) cells (not shown). The mucosa surrounding the villi forms tubular invaginations into the lamina propria, called crypts, which serve as a protected reservoir of stem and progenitor cell populations. Notably, the epithelium of the colon is devoid of villi, with the crypts opening onto a flat mucosal surface, reflecting its role in waste compaction. To support homeostatic turnover, ISCs self-renew and give rise to short-lived transit-amplifying (TA) cells, which in turn beget lineage-restricted progenitors that differentiate into the mature cell types lining the villi. During their limited lifespan, intestinal epithelial cells migrate from the base of the crypt to the tip of the villus or the colonic surface, from where they are shed into the gut lumen and replaced by neighbouring cells. In contrast, Paneth cells are relatively long-lived, and migrate to the base of the crypt, where they secrete antimicrobial peptides and form a vital component of the ISC niche. Paneth cells are absent from the colon, but deep crypt secretory (DCS) cells may fulfil an equivalent role. Opposing gradients of morphogens specify intestinal-cell fate and differentiation along the vertical crypt axis: Wnt and Notch signalling prevail at the crypt base, whereas BMP transduction is highest near the lumen.