Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

Ependymoblastoma is a malignant embryonal tumor that develops in early childhood and has a dismal prognosis. Categorized by the World Health Organization as a subgroup of CNS-primitive neuroectodermal tumor, ependymoblastoma is histologically defined by “ependymoblastic rosettes.” Because it is so rare, little is known about specific MR imaging characteristics of ependymoblastoma. We systematically analyzed and discussed MR imaging features of ependymoblastoma in a series of 22 consecutive patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Ependymoblastoma cases were obtained from the database of the German multicenter HIT trials between 2002 and 2013. All cases within this study were centrally reviewed for histopathology, MR imaging findings, and multimodal therapy. For systematic analysis of initial MR imaging scans at diagnosis, we applied standardized criteria for reference image evaluation of pediatric brain tumors.

RESULTS:

Ependymoblastomas are large tumors with well-defined tumor margins, iso- to hyperintense signal on T2WI, and diffusion restriction. Contrast enhancement is variable, with a tendency to mild or moderate enhancement. Subarachnoid spread is common in ependymoblastoma but can be absent initially. There was a male preponderance (1.75:1 ratio) for ependymoblastoma in our cohort. Mean age at diagnosis was 2.1 years.

CONCLUSIONS:

With this study, we add the largest case collection to the limited published database of MR imaging findings in ependymoblastoma, together with epidemiologic data. However, future studies are needed to systematically compare MR imaging findings of ependymoblastoma with other CNS-primitive neuroectodermal tumors and ependymoma, to delineate imaging criteria that might help distinguish these pediatric brain tumor entities.

According to the 2007 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the CNS, ependymoblastoma (EBL) is a grade IV embryonal tumor that can be categorized as a subgroup of primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET).1 The group of CNS-PNET can be further subdivided into CNS-neuroblastoma, CNS-ganglioneuroblastoma, NOS (not otherwise specified), and medulloepithelioma. EBLs are highly aggressive tumors that occur mainly in young children, with rapid growth and craniospinal dissemination. The MR imaging appearance of EBL has been described in the literature as a large, well-demarcated but heterogeneous mass with variable contrast enhancement.2 Most of the tumors are located supratentorially, followed by infratentorial and spinal sites.3 Locations outside the CNS are exceptionally rare, with published cases of congenital sacrococcygeal or ovarian tumors.4,5

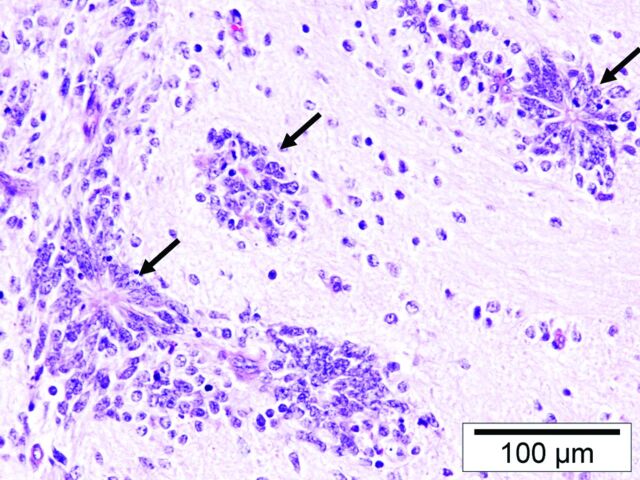

First described by Bailey and Cushing6,7 in 1926 as an ependymal-derived entity, the exact definition of EBL has since generated some controversy among neuropathologists. Rubinstein8 later characterized EBLs as primitive neuroepithalial tumors of high cellularity that show numerous and characteristic “ependymoblastic rosettes.”

We want to contribute to this ongoing discussion with the first systematic analysis of imaging characteristics of EBL. Differentiation from other primitive embryonal tumors (such as other CNS-PNET variants and medulloblastoma) by means of diagnostic imaging is challenging. Due to the rarity of this tumor, a systematic analysis of MR imaging features of EBL has not yet been performed. To determine specific diagnostic features, we report on imaging characteristics of 22 consecutive EBL cases that were collected from the prospective German Society of Pediatric Oncology and Hematology multicenter trials HIT91, HIT-SKK92, and HIT2000 (HIT is a German abbreviation for brain tumor), with central review for neuropathology, neuroradiology, and therapy.3,9,10

Materials and Methods

Study Population

EBL cases were obtained from the database of the German multicenter HIT trials.11 Cases with histolopathologic diagnosis of EBL, confirmed by central review in the Neuropathological Brain Tumor Reference Center of the German Society of Neuropathology and Neuroanatomy (T.P.), were included. Patients were diagnosed with EBL between the years 2002 and 2013. Two patients were initially diagnosed with EBL and were excluded because they showed negative immunohistochemistry for LIN28A, which has been recently proposed as a molecular marker for embryonal tumors with multilayered rosettes.12 We further excluded older cases where MR imaging (film copies) had not yet been digitized for image analysis. One patient from an external center was excluded because we lacked the initial MR imaging scans before surgery. A minimum of T1WI, T2WI, and contrast-enhanced T1WI in at least 2 different planes and without severe motion artifacts was required for cranial MR imaging scans in our study. Finally, 22 patients with sufficient preoperative cranial MR imaging scans were identified.

Image Analysis

For image analysis of our EBL cases, we used standardized MR imaging criteria according to the established routine evaluation of our Neuroradiological Reference Center for the HIT studies (as demonstrated in the On-line Table). Tumor diameter was measured in 3 dimensions (craniocaudal, left-right, anteroposterior; in cm), and tumor volume was calculated according to a common approximation formula (a × b × c × 0.5; in cm3). Tumor location was recorded (supratentorial, infratentorial, brain stem/diencephalon; related to cortex or ventricles, basal ganglia, or intraventricular location). T1- and T2-signal intensity of the tumor in relation to the signal intensity of the cerebral and cerebellar cortex was analyzed. We searched for possible cysts within the tumor, their localization (periphery, or other location) and size (small/large cysts, with a diameter >1 cm being considered as large). Furthermore, we registered hemorrhagic changes, the homogeneity of the solid tumor and the delineation of the tumor mass from the adjacent tissue (well or ill-defined). We analyzed possible peritumoral edema and the extent of edema. Another criterion was the pattern of gadolinium enhancement within the tumors (intensity, percentage of enhancing volume, homogeneity), and possible restriction of EBL in DWI. We recorded tumor staging with possible macroscopic meningeal dissemination (stage M2–M3, according to the Chang classification of CNS-PNET13) at the time of diagnosis. Finally, CT scans (with focus on calcifications and tumor attenuation) and MR spectroscopy data were analyzed when provided by the external referring centers. With respect to the multicenter approach, MR imaging studies were obtained with MR scanners of different manufacturers at 0.5–3 T field strength. Image reading was performed by 2 neuroradiologists (M.W.-M. and J.N.) in consensus.

Results

Study Population

A total of 22 consecutive patients with EBL (mean age at diagnosis 2.1 years, range 0.3–3.4 years) were analyzed for this study. There was a male preponderance with a 1.75:1 ratio (14 patients were male and 8 were female).

Image Analysis

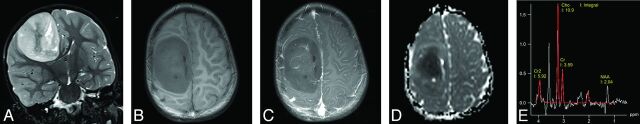

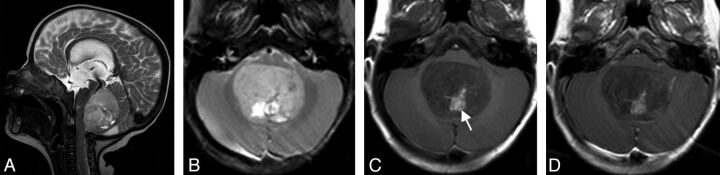

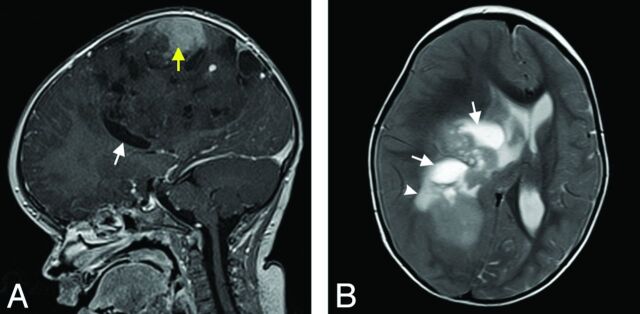

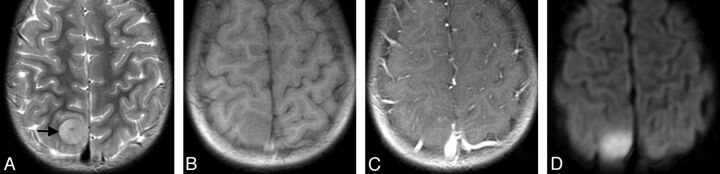

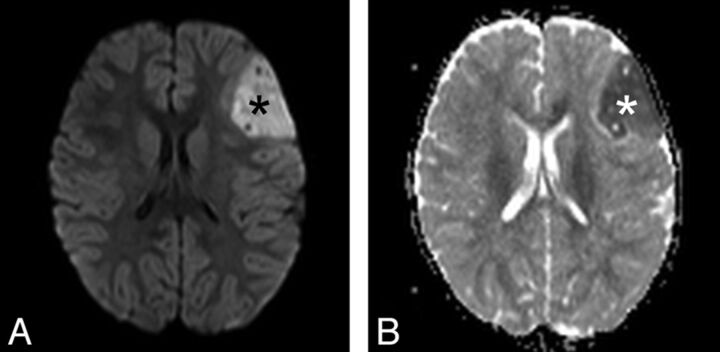

Most EBLs were located supratentorially (16 of 22 cases, Fig 1), whereas 4 tumors were found infratentorially (Fig 2) and 2 tumors occurred in the brain stem/diencephalon. The MR imaging appearance of brain stem EBL has been recently described in detail by our group.14 Mean tumor volume was 114.7 cm3 (range 3–262 cm3). Cysts could be seen in 50% of the tumors (11 of 22), of which 6 tumors (55%) showed cysts in the tumor periphery. Regarding cyst size, only 2 of 11 tumors (18%) showed large cysts (as illustrated in Fig 3). In 17 of 22 EBL cases (77%), there were signs of intratumoral hemorrhage. There was also a tendency of inhomogeneous signal appearance in T1WI and T2WI: 17 tumors (77%) showed inhomogeneous or predominantly inhomogeneous signal, and only 2 tumors showed a homogeneous signal (9%; 3 tumors = 14% with predominantly homogeneous signal), as demonstrated in Fig 4. This is also reflected by the particular analysis of T1 and T2 signal intensity. In T1WI, the predominant signal was hypo- (9 of 22, 41%) to isointense (27%). In the remaining 7 tumors (32%), different signal intensities (hypo-/iso-/hyperintense) could be found in T1WI, mainly due to partial hemorrhage and/or calcifications. In T2WI, hypo- to hyperintense signal intensities (ie, all types of signal intensities) were present in 19 of 22 cases (86%), reflecting inhomogeneous signal. The predominant T2 signal was isointense (12 cases, 55%) or hyperintense (10 cases, 45%). None of the tumors showed a predominant low (hypointense) signal intensity in T2WI. However, all analyzed tumors had sharp (19 of 22, 86%) or predominantly sharp (3 of 22, 14%) tumor margins (Fig 1) against the adjacent structures. Surrounding edema was present in only 2 of the cases with EBL (9%). DWI was available in 14 of 22 patients; in the remaining 8 cases, DWI was either not acquired or not submitted for central neuroradiologic review. All 14 tumors with available DWI showed high signal suspecting diffusion restriction, which could be confirmed by low ADC in 11 cases (Fig 1D, Fig 5B). In 3 cases, there was no ADC map available. Here, high signal in DWI with corresponding relatively low signal intensity in T2WI (not hyperintense) was considered as restricted diffusion. Hence, all 14 tumors (100%) with available DWI showed diffusion restriction. There were 17 tumors (77%) that presented with enhancement after intravenous gadolinium administration, with 6 tumors (35%) showing mild, 8 tumors (47%) moderate, and 3 tumors (18%) strong contrast enhancement. Enhancement was predominantly homogeneous in most enhancing tumors (13 cases, 76%), and completely homogeneous in 1 case (6%). A total of 2 tumors (12%) showed predominantly inhomogeneous contrast enhancement, and 1 tumor (6%) showed (completely) inhomogeneous enhancement. One tumor was found with 51%–75% gadolinium enhancement of the solid tumor component. Most EBLs (16 of 17, 94%) showed 26%–50% (7 cases) or 1%–25% (9 cases) solid tumor enhancement.

Fig 1.

Typical MR imaging of EBL (patient 11), presenting as large hemispheric tumor mass. Note the well-delineated tumor margins and absence of surrounding edema. MR signal intensity is high in T2WI (A) and iso- to hypointense in T1WI (B). The tumor shows moderate enhancement of some parts after gadolinium administration (C). ADC map shows low signal (D, see also Fig 5B). Single-voxel MR spectroscopy (E) of the tumor with a choline:NAA ratio of 5:1, indicating high cellularity. There is a small peak for lactate at 1.3 ppm. A signal for lipids was not detected in this case (3T Trio; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany).

Fig 2.

Infratentorial EBL (patient 7) of the fourth ventricle with marked displacement of the brain stem (A). T2 signal is predominantly inhomogeneous. No surrounding edema is present (B). Methemoglobin as a sign of intratumoral hemorrhage (white arrow in C). This tumor does not enhance after contrast administration (D) (1.5T Symphony; Siemens).

Fig 3.

Hemispheric EBL (patient 6) with inhomogeneous signal and moderate contrast enhancement (yellow arrow in A). Cystic components of variable size are present in the tumor (white arrows in A and B). Small peritumoral edema can be found in T2WI (white arrowhead in B). Note there is significant mass effect with midline shift. Tumor margins are less defined in some areas compared with patient 11 (Fig 1) (1.5T Symphony; Siemens).

Fig 4.

Small parasagittal EBL (patient 15) with predominantly homogeneous, isointense MR signal in T2WI (A, black arrow) and T1WI (B). Note there is diffusion restriction (D), but no intratumoral contrast enhancement (C) (1.5T Signa Excite; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin).

Fig 5.

Left hemispheric EBL of patient 5 showing restricted diffusion (black asterisk in A) with corresponding low signal in ADC map (white asterisk in B), reflecting diffusion restriction and high cellularity. This finding was observed in every patient with EBL of our cohort (3T Verio; Siemens).

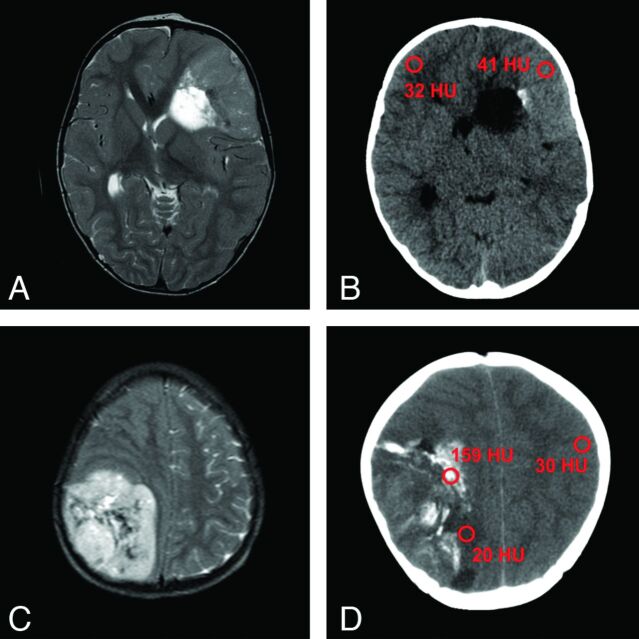

More than two-thirds of our EBL cases (17 of 22, or 77%) did not show imaging evidence of meningeal dissemination (indicating macroscopic dissemination) at presentation. In addition, we lacked spinal MR imaging scans for 4 cases and hence CNS macroscopic dissemination status remained unclear. At presentation, 6 of 7 patients (86%) with complete intracranial and spinal MR imaging datasets did not have positive imaging signs (M2 and/or M3) of meningeal dissemination. One patient had M3 stage (spinal CNS dissemination). Another patient presented with a solitary M2 stage (intracranial dissemination). However, spinal datasets were incomplete in this patient (according to our internal standard of MR acquisition parameters; see Discussion), in another 2 patients with proposed M3 stage, and in 2 patients with proposed M2 and M3 stage (intracranial and spinal dissemination). In the remaining patients, the exact status of possible CNS spread remained unclear from our neuroradiologic perspective. Single-voxel MR spectroscopy data were available for only 3 patients (14%), and showed an increase in the choline:NAA ratio up to 5:1, compared with normal brain tissue (Fig 1E). Additional CT scans were submitted in 5 of our 22 cases (23%), with EBL showing different solid components from hypoattenuation (minimum of 20 Hounsfield units) to hyperattenuation (maximum of 41 Hounsfield units), compared with cortex (Fig 6B, -D). In 3 cases (60%), there were calcifications within the tumors (60%). Typical histopathologic appearance of EBL is demonstrated in Fig 7.

Fig 6.

T2WI of 2 EBLs with corresponding CT scans of patient 12 (A, B) and patient 19 (C, D). Note almost T2 isointense signal of the tumor in (A) with slight hyperattenuation in the corresponding CT image (B). This tumor is indicative of higher cellularity, compared with the EBL shown in (C) and (D). Calcifications such as in (D) can complicate the detection of components with high cellularity. Region of interest in red showing Hounsfield units of tumors, normal cortex, and calcifications (A, 1.5T Signa Excite, GE Healthcare; B, Sensation 16, Siemens; C, 0.5T NT Intera, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands; D, Lightspeed Plus, GE Healthcare).

Fig 7.

Typical histopathologic finding of EBL (patient 1) with ependymoblastic rosettes (black arrows).

Discussion

Study Population

With this series comprising 22 MR imaging studies of EBL, we present detailed imaging characteristics of this rare pediatric CNS tumor entity. In addition to imaging features, our study also provides epidemiologic information of EBL. We found a male to female ratio of 1.75:1 in our patient collective. In all CNS-PNETs, this ratio has been reported with 1.4:1, according to the annual report of the German Childhood Cancer Registry.15 The mean age at diagnosis for all CNS-PNETs in this registry was 4 years 0 months, whereas mean age at diagnosis of EBL was 2.1 years in our study. Thus, it seems that there might be a male preponderance for EBL and other CNS-PNETs (with a slightly stronger tendency for EBL in males), and a younger age at diagnosis in EBL, compared with other CNS-PNETs. There are currently no data available in the literature about mean age at diagnosis, incidence, or sex and race predisposition of EBL. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End-Results database, neither sex nor race was a predictor for CNS-PNET development.16

Image Analysis

To date, only very limited MR imaging data are available from few case reports.3,17–21 Histologically designated as a subgroup of CNS-PNET, EBL seems to share imaging features with (other) CNS-PNETs. On MR imaging scans, EBL and other CNS-PNETs appear as large, heterogeneous tumor masses with iso- to hyperintense signal to gray matter on T2WI, pointing to increased cellularity.22,23 This is further supported by restricted diffusion (100% of our EBL cases) and decreased ADC, which has been reported for other CNS-PNETs as well.24 In addition, necrosis and hemorrhage are common in CNS-PNET and in our EBL cases (77%). The solid tumor component of CNS-PNET has been described with avid heterogeneous gadolinium enhancement in the literature.25 For EBL, we found mild to moderate enhancement in most cases (6 and 8 of 22, respectively). Only 3 cases showed strong enhancement, whereas 5 patients did not show any contrast enhancement. Surrounding edema seems to be only minimal in both EBL (9% in our study) and other CNS-PNETs.23 Calcifications are seen in up to 70% of CNS-PNETs, with iso- to hyperattenuating appearance in CT.22,26 This is relatively consistent with our EBL cases (60% calcifications), though we analyzed only 5 tumors with available CT scans. MR spectroscopy findings in CNS-PNET are characterized by marked elevation of taurine and choline levels with low creatine.26,27 We are the first to demonstrate MR spectroscopy findings in EBL, with a high choline:NAA ratio pointing to increased cell turnover, similar to CNS-PNET. It is not yet clear whether MR spectroscopy might be useful to distinguish CNS-PNET variants from EBL and other brain tumors in the clinical setting. Considering evolving techniques such as perfusion MR imaging and DTI, we lack data to further characterize EBL. Perfusion MR imaging in CNS-PNET showed increased relative CBV values that might result from vascular endothelial hyperplasia and increased permeability, as seen in other high-grade tumors.28 Furthermore, DTI has been applied for the evaluation of postradiation white matter changes in children with brain tumors including CNS-PNET, medulloblastoma, atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor, and high-grade gliomas.29

A limitation of our study might be that most of the MR imaging cases were provided by external centers because of the multicentric nature of the HIT studies. Only 2 of 22 patients were treated in our clinic. Thus, cranial MR imaging datasets were of different quality, according to field strength (0.5–3T) and image acquisition parameters. To address the issue of heterogeneous MR imaging quality, all 22 cases were centrally reviewed regarding MR imaging findings by the Reference Center for Neuroradiology (M.W.-M.).

EBL and other CNS-PNETs are highly malignant tumors, with aggressive growth and subarachnoid spread. It has been shown that about 40% of patients with supratentorial CNS-PNET or medulloblastoma show meningeal dissemination at presentation.22 Spinal MR imaging is therefore strongly recommended and important for treatment and prognosis. Similar to cranial MR imaging, a difficulty in our study was the diverging image quality (section thickness, pulsation artifacts, sequence parameters) of the available spinal MR imaging scans. A total of 11 patients did not meet all quality criteria of our Reference Center, and hence diagnostic value of possible CNS spread of EBL within our study was limited. Being focused on tumor imaging in EBL, we do not provide data regarding possible M0 or M1 stage at presentation.

Histopathologic Diagnosis of EBL

The exact histopathologic diagnosis of EBL has its own controversial history. Bailey and Cushing6 first proposed EBL as a specific diagnostic entity in 1926, characterized by the presence of “ependymal spongioblasts” (tumor cells with cytoplasmic processes that form “pseudorosettes”), separating EBL from ependymoma.30 However, they later abandoned the term EBL, retaining “ependymoma” as the preferred designation. Rubinstein8 reintroduced EBL as a malignant CNS tumor entity of young children in 1970, characterized by undifferentiated morphology and the presence of multilayered proliferative rosettes with a lumen (ependymoblastic rosettes). Recently, a primitive tumor termed an embryonal tumor with abundant neuropil and true rosettes (ETANTR) has been proposed as a novel CNS tumor entity by some authors.31 They argue that combined features of EBL and neuroblastoma, containing multilayered ependymoblastic rosettes (“true” rosettes), define a separate novel histologic tumor entity with poor outcome.7,31,32 However, this largely overlaps with the original descriptions by Rubinstein,8 probably representing the identical phenotype and diagnosis. Recent molecular studies further clearly demonstrate that tumors diagnosed as EBL, ETANTR, or embryonal tumors with multilayered rosettes carry identical, highly specific chromosomal alterations (amplification at 19q and/or gain of chromosome 2).33 EBL and the proposed “novel” entities therefore represent a single embryonal tumor entity (defined as EBL according to the 2007 World Health Organization classification).1,12,33,34 Consequently, all 22 tumors of our case collection were designated EBL by central neuropathologic review (T.P.). We intend to contribute to this ongoing discussion with the first systematic analysis of imaging characteristics of EBL.

Conclusions

The case series presented here is the largest collection of MR imaging data for EBL to date. Imaging appearance of EBL seems to share features with other pediatric embryonal CNS tumors. However, a systematic analysis that compares imaging findings of EBL with (other) CNS-PNETs and ependymoma is needed to evaluate possible differences in image appearance of these entities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Kinderkrebsstiftung (German Childhood Cancer Foundation). We furthermore thank Emily Decelle and György A. Homola for their help with manuscript editing.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- EBL

ependymoblastoma

- PNET

primitive neuroectodermal tumor

Footnotes

Disclosures: Katja von Hoff—UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: German Childhood Cancer Foundation.* Stefan Rutkowski—UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: German Childhood Cancer Foundation,* Comments: funding of the HIT trial office, where patients' data have been collected, and supporting other studies of the HIT trial office. Monika Warmuth-Metz—UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: German Childhood Cancer Foundation,* Comments: German Childhood Cancer Foundation is an association of parents with children with leukemia and tumors supporting the Radiological Reference Center; Consultancy: Roche, Oncoscience, Comments: for glioma studies separate from the HIT studies; Expert Testimony: Oncoscience, Comments: related to glioma studies other than the HIT studies; Travel/Accommodations/Meeting Expenses Unrelated to Activities Listed: Roche, Oncoscience. *Money paid to the institution.

REFERENCES

- 1. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osborn AG. Osborn's Brain: Imaging, Pathology, and Anatomy. Salt Lake City: Amirsys; 2013:573–75 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gerber NU, von Hoff K, von Bueren AO, et al. Outcome of 11 children with ependymoblastoma treated within the prospective HIT-trials between 1991 and 2006. J Neurooncol 2011;102:459–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morovic A, Damjanov I. Neuroectodermal ovarian tumors: a brief overview. Histol Histopathol 2008;23:765–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Santi M, Bulas D, Fasano R, et al. Congenital ependymoblastoma arising in the sacrococcygeal soft tissue: a case study. Clin Neuropathol 2008;27:78–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bailey P, Cushing H. A Classification of the Tumors of the Glioma Group on a Histogenetic Basis With a Correlated Study of Prognosis. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co.; 1926 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Judkins AR, Ellison DW. Ependymoblastoma: dear, damned, distracting diagnosis, farewell!*. Brain Pathol 2010;20:133–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rubinstein LJ. The definition of the ependymoblastoma. Arch Pathol 1970;90:35–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rutkowski S, von Bueren A, von Hoff K, et al. Prognostic relevance of clinical and biological risk factors in childhood medulloblastoma: results of patients treated in the prospective multicenter trial HIT'91. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:2651–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. von Hoff K, Hinkes B, Gerber NU, et al. Long-term outcome and clinical prognostic factors in children with medulloblastoma treated in the prospective randomised multicentre trial HIT'91. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1209–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Friedrich C, von Bueren AO, von Hoff K, et al. Treatment of young children with CNS-primitive neuroectodermal tumors/pineoblastomas in the prospective multicenter trial HIT 2000 using different chemotherapy regimens and radiotherapy. Neuro Oncol 2013;15:224–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Korshunov A, Sturm D, Ryzhova M, et al. Embryonal tumor with abundant neuropil and true rosettes (ETANTR), ependymoblastoma, and medulloepithelioma share molecular similarity and comprise a single clinicopathological entity. Acta Neuropathol 2014;128:279–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Laurent JP, Chang CH, Cohen ME. A classification system for primitive neuroectodermal tumors (medulloblastoma) of the posterior fossa. Cancer 1985;56:1807–09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nowak J, Seidel C, Pietsch T, et al. Ependymoblastoma of the brainstem: MRI findings and differential diagnosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:1132–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. German Childhood Cancer Registry. Annual Report 2011. http://www.kinderkrebsregister.de/fileadmin/kliniken/dkkr/pdf/jb/jb2010/jb2010_2_Diagnosen.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2014.

- 16. Smoll NR, Drummond KJ. The incidence of medulloblastomas and primitive neurectodermal tumours in adults and children. J Clin Neurosci 2012;19:1541–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cervoni L, Celli P, Trillo G, et al. Ependymoblastoma: a clinical review. Neurosurg Rev 1995;18:189–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dorsay TA, Rovira MJ, Ho VB, et al. Ependymoblastoma: MR presentation. A case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol 1995;25:433–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nejat F, Kazmi SS, Ardakani SB. Congenital brain tumors in a series of seven patients. Pediatr Neurosurg 2008;44:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ng SH, Ko SF, Chen YL, et al. Ependymoblastoma: CT and MRI demonstration. Chin J Radiol 2002;27:21–25 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ortiz J, Otero A, Bengoechea O, et al. Divergent ependymal tumor (ependymoblastoma/anaplastic ependymoma) of the posterior fossa: an uncommon case observed in a child. J Child Neurol 2008;23:1058–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chawla A, Emmanuel JV, Seow WT, et al. Paediatric PNET: pre-surgical MRI features. Clin Radiol 2007;62:43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Newton H, Jolesz F. Handbook of Neuro-Oncology Neuroimaging. New York: Elsevier; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gauvain KM, McKinstry RC, Mukherjee P, et al. Evaluating pediatric brain tumor cellularity with diffusion-tensor imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;177:449–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Poussaint TY. Magnetic resonance imaging of pediatric brain tumors: state of the art. Top Magn Reson Imaging 2001;12:411–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Borja MJ, Plaza MJ, Altman N, et al. Conventional and advanced MRI features of pediatric intracranial tumors: supratentorial tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;200:W483–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kovanlikaya A, Panigrahy A, Krieger MD, et al. Untreated pediatric primitive neuroectodermal tumor in vivo: quantitation of taurine with MR spectroscopy. Radiology 2005;236:1020–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Law M, Kazmi K, Wetzel S, et al. Dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced perfusion and conventional MR imaging findings for adult patients with cerebral primitive neuroectodermal tumors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:997–1005 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hua C, Merchant TE, Gajjar A, et al. Brain tumor therapy-induced changes in normal-appearing brainstem measured with longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:2047–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Godfraind C. Classification and controversies in pathology of ependymomas. Childs Nerv Syst 2009;25:1185–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eberhart CG, Brat DJ, Cohen KJ, et al. Pediatric neuroblastic brain tumors containing abundant neuropil and true rosettes. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2000;3:346–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gessi M, Giangaspero F, Lauriola L, et al. Embryonal tumors with abundant neuropil and true rosettes: a distinctive CNS primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:211–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Korshunov A, Remke M, Gessi M, et al. Focal genomic amplification at 19q13.42 comprises a powerful diagnostic marker for embryonal tumors with ependymoblastic rosettes. Acta Neuropathol 2010;120:253–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ceccom J, Bourdeaut F, Loukh N, et al. Embryonal tumor with multilayered rosettes: diagnostic tools update and review of the literature. Clin Neuropathol 2014;33:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.