Abstract

Introduction

Freshwater ecosystems provide propitious conditions for the acquisition and spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), and integrons play an important role in this process.

Material and methods

In the present study, the diversity of putative environmental integron-cassettes, as well as their potential bacterial hosts in the Velhas River (Brazil), was explored through intI-attC and 16S rRNA amplicons deep sequencing.

Results and discussion

ORFs related to different biological processes were observed, from DNA integration to oxidation-reduction. ARGs-cassettes were mainly associated with class 1 mobile integrons carried by pathogenic Gammaproteobacteria, and possibly sedentary chromosomal integrons hosted by Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria. Two putative novel ARG-cassettes homologs to fosB3 and novA were detected. Regarding 16SrRNA gene analysis, taxonomic and functional profiles unveiled Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria as dominant phyla. Betaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, and Actinobacteria classes were the main contributors for KEGG orthologs associated with resistance.

Conclusions

Overall, these results provide new information about environmental integrons as a source of resistance determinants outside clinical settings and the bacterial community in the Velhas River.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-020-00409-8.

Keywords: Environmental integron-cassettes, Antibiotic resistance, Urban river microbiome, 16S rRNA gene

Introduction

Aquatic environments have been recognized as a major reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), particularly those receiving antibiotics used in agriculture, animal breeding, and hospitals, as well as biocides and heavy metals [1]. The environmental resistome is influenced by many intertwined factors, including the anthropogenic impact type and magnitude, and selective pressure imposed by biotic and abiotic conditions.

Regarding human health, there is a growing concern that environmental ARGs could be spread by horizontal gene transfer, establishing a link between natural and clinical settings, although this connection is not fully understood [2]. However, since antibiotics are generally not removed in drinking nor wastewater treatment plants, they could reach larger water bodies, sediments, and soils, altering the microbial community composition and contributing to the emergence of resistant bacteria [3].

It is well established that mobile genetic elements (MGEs) are crucial for antibiotic resistance dissemination. Although unable to transfer themselves, integrons are often associated with MGEs, e.g., conjugative plasmids and transposons, and then named mobile integrons (MIs), and are important contributors to the spread of ARGs [4, 5]. When in the chromosome (sedentary chromosomal integrons, or SCIs), integrons can harbor large gene cassette arrays, mostly with cryptic functions [5]. It is worth noting that MIs can also be found in MGEs located on chromosomes, like integrative conjugative elements [6]. Moreover, the evolutionary history of integrons suggests that SCIs might constitute a gene cassette reservoir that could be a source of contemporary MIs, due to their capacity to capture, reorder, and express diverse gene cassettes [7].

All integrons have the same basic structure, composed of an integrase gene intI, an attI recombination site, and a Pc promoter, enabling the transcription of gene cassettes. Typical cassettes are comprised of a promoterless open reading frame (ORF), encoding a variety of functions, followed by a conserved recombination site, attC [4]. Although the sequence and length of the attC sites are highly variable, they harbor conserved sequences named inverse core (5’ RYYYAAC) and core (3’ GTTRRRY), which form a secondary hairpin structure important for successful recombination [5].

The taxonomic distribution of integrons among bacteria is uneven; they are present in 6% of sequenced bacterial genomes on average but can reach 20% in Gammaproteobacteria [8]. More than 100 classes of integrons have been described from a variety of environments [9]. Given its clinical relevance, class 1 integrons, followed by classes 2 and 3, are the most frequent, and have been reported in different environments [10, 11].

Over the last decades, research on integrons generally employed culture-dependent, cloning, and Sanger sequencing-based methods, or focused on specific integron classes, which have brought significant insights, but present shortcomings in revealing the diversity of cassettes. Despite the increase in the number of studies employing shotgun metagenomics to investigate the dissemination of ARGs and the associated mobilome, this approach has higher sequencing costs and computational demand, given that the vast majority of the sequences are not associated with resistance nor integrons. A cost-effective alternative for thoroughly exploring resistance cassettes is intI-attC amplicons deep sequencing, which has been successfully applied in other studies [12, 13].

In this context, this work investigated the abundance and diversity of integron-associated ARGs in the bacterioplankton community from the Velhas River (MG/Brazil), which waters are used for human consumption, irrigation, wastewater discharge, and industrial activities. Additionally, to explore the bacterial community in the studied environment, taxonomic composition analysis and prediction of resistance determinants based on 16S rRNA gene were performed.

Materials and methods

Study area, sampling, and water physicochemical characteristics

Sampling was performed at the Velhas River (20.00S, 43.82 W, Nova Lima city, Minas Gerais state, Brazil), which has approximately 800 km long, with a watershed area of 29,173 km2. The river course is divided into three regions, upper, medium, and lower [14]. The upper course, where the sampling site is located, is associated with human consumption, industrial activity, and public supply. At the sampling point, it is classified as class 2, which corresponds to waters intended for domestic supply after conventional treatment. Detailed information about water quality parameters at different points of the river are provided by the Instituto Mineiro de Gestão das Águas [14].

The Velhas River has a rainfall regime, and from October to March, the water level can significantly increase. Throughout these months, soil and sediment particles are dragged into the water column, raising its color and turbidity. To better represent the riverine microbiome, three sampling campaigns were performed from March to May (one sample per month), which correspond to the end of the rainy season and the beginning of the dry season in Minas Gerais. Two liters of surface water were collected and sequentially filtered through sterilized 20 μm (to retain large particulate solids) and 0.22-μm membranes (Millipore, USA). Nine 0.22-μm membranes (three for each sample) were stored at − 20 °C until further processing. Color, conductivity, pH, temperature, turbidity, and pluviosity values at the sampling site are shown in Online Resource 1.

DNA extraction, library construction, and sequencing

Total DNA was extracted with EZNA® Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, USA), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. DNA quantification and quality were assessed with Qubit® fluorometer and Nanodrop 2000® spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), respectively. Amplification of integron-cassettes was performed using the primers IntI-864R: 5’-YAGCAGATGNGTGGCRAAVSWRTGSCG-3’and GCP2: 5’-TCSGCTKGARCGAMTTGTTRRRY-3’ [15]. This primer pair targets the integrase gene intI and a conserved region of the attC recombination site. The amplification program, adapted from Elsaied et al. [16], consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, primer annealing and extension at 60–62 °C (1 °C increase at each 10 cycles) for 15 min, and a final extension step at 68 °C for 15 min. PCR and libraries construction were, respectively, performed with KAPA LongRange HotStart PCR Kit (amplifies targets up to 15 kb with high sensitivity and specificity) and KAPA HyperPlus Kit (KAPA-Roche, Switzerland), based on the manufacturer’s recommendations. PCR results were assessed through 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. To adjust the variable-sized amplicons for the desired length (~ 400 bp), library construction comprised different times of DNA tagmentation for each sample. For bacterial community analysis, amplicons of V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene were obtained using Illumina adapter-containing modified primers 515FB (5′- GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 806RB (5′- GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) [17, 18]. 16S libraries were constructed according to the protocol provided by Illumina. All DNA extractions and PCR reactions were performed separately for each 0.22-μm membrane, and the amplicons were pooled for library construction. Integron-cassettes and 16S libraries were sequenced in two separated runs, at MiSeq platform (Illumina, USA), with Miseq Reagent Kit v2 (2 × 250 bp). The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI database under the accession number PRJNA432952.

Integron-cassettes sequences processing and annotation

Bioinformatics analysis used to explore the general diversity of cassettes consisted of the following steps (summarized in Online Resource 2): raw reads were filtered and trimmed with Trimmomatic [19], and their quality assessed with FastQC [20]. Assembly was performed with metaSPAdes [21], using default parameters. Contigs with at least 200 nucleotides length were included in the next steps. Gene prediction was performed with Prodigal [22], followed by annotation with InterProScan [23]. Only alignments ≥ 20 amino acids and score < 1e−5 were considered for further analysis.

Resistance profile was investigated aligning the predicted amino acids sequences to CARD using blastp. For that, the following criteria (adapted from Tanenbaum et al. [24]) were used: alignments with an e value < 1e−5 were classified as “high confidence” (identity ≥ 35% and coverage ≥ 80%) or “putative” (identity < 35% and coverage ≥ 80%). Additionally, CARD significant matches were also searched in INTEGRALL database [25]. Finally, contigs harboring these ORFs were compared to nt/NCBI with blastn [26], with a minimum e value of 1e−5.

For confirming amplification specificity, the presence of attC recombination sites in the contigs was investigated with HattCI [27], using a Viterbi score ≥ 5. Contigs without attC sites (which could include valid cassettes at the first position) were aligned to 5779 integron-integrase sequences downloaded from RefSeq/NCBI with blastx, and those with significant alignments (e value < 1e−5, identity ≥ 35% and coverage ≥ 80%) were also considered for subsequent analysis. In order to exclude non-cassettes ORFs from the pool, those annotated as recombinases were inspected in regard with the attC site position (< 200 pb from the ORF start or end was considered a possible gene cassette). Visualization of gene ontology (GO) terms was performed with REVIGO [28], with allowed similarity of 0.9.

Microbiota analysis

Sequences of 16S rRNA gene with a minimum length of 200 bp were initially filtered with AfterQC [29], and bacterial community analysis was performed with QIIME [30]. Chimeras were removed with USEARCH algorithm [31]. For taxonomic profile and diversity analysis, sequences were grouped into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with pick_open_reference_otus.py (with 97% similarity threshold) based on Greengenes v.13.8 database [32]. Singletons, chloroplasts, and mitochondria reads were removed. Alpha-diversity analysis was performed with the R package Phyloseq [33]. PICRUSt [34] was used to predict the community-associated functional characteristics based on KEGG orthologs (KOs). For that, OTUs were determined with QIIME pick_closed_reference_otus.py command and precalculated reference files based on Greengenes v.13.5. The taxa contributing to the most frequent KOs (> 0.1%) associated with antibiotic resistance were then estimated.

Results

Sequencing overview and integron-cassette encoded functions

In the present work, the diversity of environmental integron-cassettes was explored trough intI-attC amplicons deep sequencing, with focus on antibiotic resistance. A total of 3,426,527 high quality reads were generated; 1724 contigs with an intI gene (high confidence alignments) or an attC site (Viterbi score ≥ 5) were identified, harboring 2081 ORFs (ranging from 60 to 1629 bp); and 320 contigs had two or more ORFs (one to five ORFs per contig).

Significant annotations in InterProScan showed diverse cassette-encoded functions (GO terms), comprising 13 biological processes (Fig. 1), among which the most frequent were DNA integration, followed by oxidation-reduction (91% of all annotated cassette-related ORFs did not have any associated GO term). The results indicate that most integron-cassettes observed in the present study are involved with cryptical functions, confirming that these elements can harbor a vast and unexplored pool of genes, possibly including novel resistance determinants.

Fig. 1.

REVIGO analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) terms related to biological processes in all samples (http://revigo.irb.hr/), with allowed similarity of 0.9. Bubble color and size indicate the relative frequency of a GO term in the samples and in the Whole UniProt database, respectively (larger bubbles refer to more general terms)

Detection of ORFs associated with antibiotic resistance

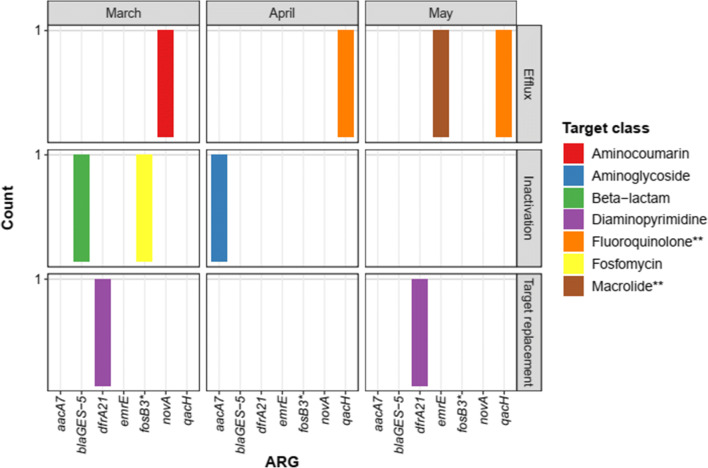

A total of nine ORFs associated with antibiotic resistance were identified, comprising seven different ARGs and corresponding to 1% all cassette-related ORFs (Fig. 2). Seven ARGs-ORFs were near attC sites, and two were in tandem with integron-integrase sequences (classified as blaGES-5 and novA). ARGs-cassettes previously described in integrons, i.e., aacA7, dfrA21, blaGES-5, qacH, and Escherichia coli emrE predominated. The latter is possibly related to the small multidrug resistance (SMR) family qac genes. It should be noted that two predicted ORFs were homologs to fosB3 and novA, which have not been associated with the integron-cassette system so far, to the best of our knowledge. Additional information on ARGs-cassettes not found in the INTEGRALL database is shown in Online Resource 3 (including the putative gene ermE).

Fig. 2.

Integron-cassette ORFs classified as antibiotic resistance genes according to the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD). * indicates a putative gene—alignments with e value < 1e−5 were classified as “high confidence” (identity ≥ 35% and coverage ≥ 80%) or “putative” (identity < 35% and coverage ≥ 80%). **: qacH and emrE are generally associated with resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds and cations like ethidium bromide, respectively, but can confer resistance to some antibiotic classes as well

In an exploratory way, there were differences in antibiotic resistance profile between months, for example, the ORF identified as fosB3 in March, aacA7 in April, and emrE in May. Overall, resistance to diaminopyrimidine and fluroquinolone was more frequent. Other target classes were aminocoumarin, aminoglycoside, beta-lactam, fosfomycin, and macrolide. The main resistance mechanisms were antibiotic efflux (four ORFs) and inactivation (three), followed by antibiotic target replacement (two). Two cassette arrays containing ARGs flanked by attC were observed, both with qacH and different hypothetical proteins.

To explore the association of resistance cassettes with possible bacterial hosts, contigs containing ORFs identified as ARGs were aligned to nt/NCBI database (e value < 1e−5, Table 1). Significant alignments with class 1 integrons of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were observed. One contig aligned with the genome of a bacterium commonly found in riverine environments, Acidovorax sp., one with Ilumatobacter coccineus (Actinobacteria) and two with the genome of a novel and recently described species, Lysobacter oculi [35]. Screening their complete genomes with IntegronFinder and HattCI indicated the presence of integron-related elements, thus reinforcing these genera as potential hosts of the gene cassettes. Overall, these results suggest that, although environmental integrons carrying ARGs are present in MGEs of pathogenic Gammaproteobacteria, they can also be found in the chromosomes of different bacterial species.

Table 1.

Matches between contigs harboring antibiotic resistance genes in nt/NCBI database

| Sample | Gene | Potential host | Location | Query coverage (%) | Identity (%) | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March | blaGES-5 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Plasmid | 58 | 99.68 | MH053445.1 |

| March | dfrA21 | Escherichia coli | Class 1 integron | 93 | 100.00 | FR875296.1 |

| March | fosB3 | Acidovorax sp. | Genome | 70 | 66.67 | CP016447.1 |

| March | novA | Ilumatobacter coccineus | Genome | 61 | 67.49 | AP012057.1 |

| April | aacA7 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Class 1 integron | 94 | 99.54 | EF660562.1 |

| April | qacH | Lysobacter oculi | Genome | 69 | 99.64 | CP029556.1 |

| May | emrE | Uncultured bacterium | Class 1 integron | 78 | 99.62 | KF525338.1 |

| May | dfrA21 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Integron | 100 | 99.66 | GQ139471.1 |

| May | qacH | Lysobacter oculi | Genome | 100 | 98.23 | CP029556.1 |

Taxonomical and functional analysis based on 16S rRNA gene

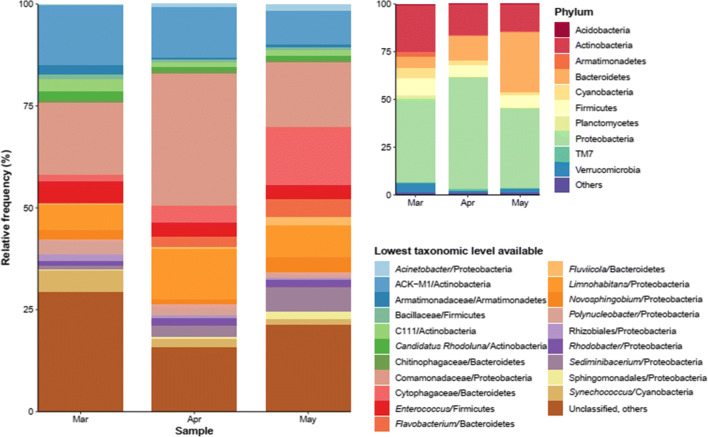

16S rRNA gene reads were grouped into 4586, 2253, and 2703 OTUs for March, April, and May samples, respectively. A total of 51 phyla (one unassigned) were identified. Taxonomic composition was similar among samples at both phylum and lower taxonomic levels, although variations in their relative frequencies have been observed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Top 10 phyla and 20 taxa at the lowest taxonomic level available of bacterioplankton community in the Velhas river samples from March, April, and May

The bacterioplankton community was dominated by members of Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes, with mean relative frequencies of 48.1, 16.8, 18.3, and 7.1%, respectively, comprising 90.3% of the total riverine microbiome, on average. A pronounced raise in Bacteroidetes proportion over time can be observed (6 to 31.3%), while Actinobacteria’s frequency diminished (from 24.8 to 14%), as shown in Fig. 3. For Proteobacteria, there was no clear pattern, and Firmicutes had a relatively even distribution in all samples (8.7, 6, and 6.5%).

An exploratory analysis of alpha-diversity (observed OTUs, Chao1, and Shannon index) indicated that the community of March was the most diverse, followed by May and April (Online Resource 4). This could possibly be a consequence of the Velhas River rainfall regime (Online Resource 1), as pluviosity decreases progressively from the end of the rainy season.

At finer taxonomic resolutions, the most frequent OTUs included unclassified Comamonadaceae, Limnohabitans, ACK-M1 family (Actinobacteria), unclassified Cytophagaceae, Enterococcus, Sediminibacterium, Synechococcus, and Polynucleobacter, although their relative frequencies have varied (e.g., Limnohabitans spp. went from 6.1% in March to 12.5% in April and 7.8% in May; unclassified Cytophagaceae, from 1.5 to 4.2 and then to 14.3%). Less frequent taxa included Acinetobacter and Fluviicola, among others.

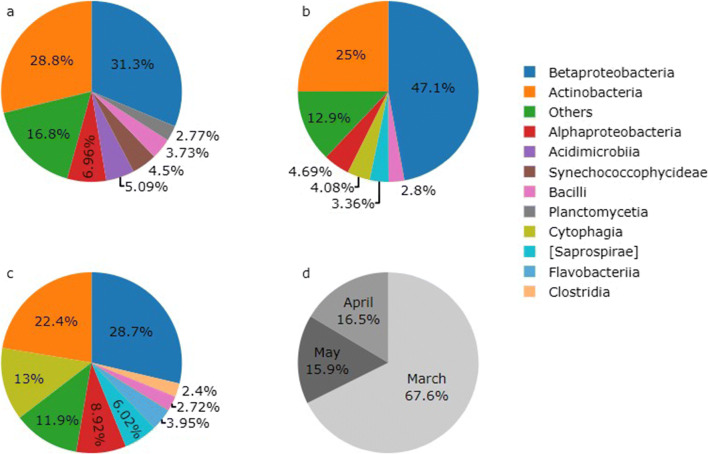

To investigate the resistance profile associated with the observed bacterial community, the 16S rRNA gene dataset was used for functional prediction with PICRUSt. The Nearest Sequenced Taxon Index (NSTI), an estimative of the availability of close representative genomes, ranged from 0.07 to 0.09, indicating reliable predictions [34]. Taxa associated with antibiotic resistance KOs (> 0.1% on average), mostly multidrug efflux pumps of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters superfamily, are presented in Fig. 4. Other related KOs included transporters of major facilitator and resistance-nodulation division superfamilies (MFS and RND, respectively). Betaproteobacteria (mostly Comamonadaceae family, and Hydrogenophaga and Ramlibacter genera) was the main class contributing with antibiotic resistance KOs in all samples (Fig.4a–c), followed by Actinobacteria (ACK-M1 family and other Actinomycetales) and Alphaproteobacteria (mainly Sphingomonadaceae family). March sample contributed the most for these KOs (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

PICRUSt metagenome contributions per gene families potentially associated with antibiotic resistance at class level. (a) March, (b) April, (c) May, (d) percentage contributions of each sample (not in the legend)

Discussion

Integrons are important contributors for ARGs dissemination, although environmental integrons are largely unknown. In the present work, known and putative novel gene cassettes associated with antibiotic resistance were observed in intI-attC amplicons from the Velhas River samples. Most ORFs had cryptic functions, and ARGs corresponded to a small fraction of the total.

Genomic and metagenomic studies with different hosts and environments have demonstrated that gene cassettes are extremely diverse, comprising many unknown functions [36]. Among the identified ORFs, general metabolic processes, e.g., oxidation-reduction, were more frequent, as reported elsewhere [37].

ARGs-cassettes represented a small proportion of the total of the cassette-related ORFs. This observation is consistent with other studies reports that resistance cassettes abundance is relatively low compared to their diversity [6, 37]. Additionally, known ARGs-cassettes still represent a small fraction of the environmental resistance pool, despite the progressive increase in related databases [38].

The sampling point is located at the upper course of the Velhas River, characterized by an intensive water demand for both human consumption and industrial supply. It is worth noting that mining activities also take place at this region [14], which can compromise the water quality through the discharge of many pollutants, such as heavy metals. This characteristic may also have influenced the microbial community and the variability of the cassette pool. It is well established that class 1 integrons are the most clinically relevant and widespread, and its abundance has been associated with the environment pollution level [11]. Nevertheless, at the sampling point, the river is classified as class 2 (referring to waters intended for domestic supply after conventional treatment) [14], indicating considerable, although not high, anthropogenic impact.

Resistance to seven antibiotic classes was observed in the present study, mainly associated with efflux pumps (Fig. 2). Most of the target classes, like quinolone, aminoglycoside, beta-lactam, and macrolide, are included in the WHO’s list of critically important antimicrobials used in human medicine [39]. Cassettes encoding resistance to these targets, as well as to diaminopyrimidines, are frequent in class 1 MIs, and have been previously reported in environmental and clinical settings [40–42].

Among the putative ARGs-ORFs observed in this study, there were those previously described as cassettes (aacA7, blaGES-5, dfrA21, E. coli ermE, and qacH), and two not previously associated with integrons (fosB3 and novA). It is worth mentioning that the sequence homolog to blaGES-5 (carbapenem resistance) was associated with a plasmid of P. aeruginosa (Table 1). In Brazil, blaGES-5 was first detected in 2009, in a class 1 integron of the same species [43]. Since then, it has been consistently retrieved from clinical settings and seldom from other environments [44].

Regarding qacH and emrE, they are generally associated with resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds and cationic substances such as ethidium bromide, respectively, but can confer resistance to some antibiotic classes as well. For example, Yerushalmi et al. [45] observed that cells expressing emrE showed higher resistance to erythromycin (macrolide) and sulfadiazine (although in CARD it is linked with macrolide resistance only), and Buffet-Bataillon et al. [46] reported that the overexpression of qac genes augmented resistance to fluoroquinolones. Considering that E. coli ermE is similar to SMR transporters family qac genes, misleading annotations may occur [47]. In this way, a stringent blast search was performed in nt/NCBI database, and the nucleotide sequence (Online Resource 3) aligned significantly (100% identity and coverage) with a class 1 integron putative qac variant (accession number KF525338.1).

With reference to the ORFs not previously observed in integrons, there was one alignment with FosB3 amino acid sequence (involved in fosfomycin inactivation) in CARD, although with a low identity value (28%), which suggests it might be a somewhat similar protein. A search in NCBI’s conserved domain database indicated an association with VOC superfamily, to which fosB3 belongs. However, this domain can be found in diverse metalloproteins. Considering that the contig harboring this ORF aligned significantly with Acidovorax sp. genome (Table 1) and that fosB3 is a plasmid-mediated resistance determinant [48], it is likely that the ORF observed here is another member of VOC family which shares similar features with fosB3. Further studies are necessary to confirm the identity and functionality of this ORF.

novA, for instance, encodes a type III ABC transporter conferring resistance to novobiocin (aminocoumarin) and has been identified in the novobiocin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces sphaeroides [49]. Here, a similar ORF was observed after an integron-integrase sequence (Online Resource 3), possibly associated with Ilumatobacter coccineus genome (Actinobacteria). Integrons of classes 1, 2, and 3 have been reported among Actinobacteria, which harbors many antibiotic producer species and consequently resistance genes, as a self-defense mechanism against antibacterial compounds [50]. One attC site (with Viterbi score ≥ 5) was identified in I. coccineus genome, although other integron-like elements were not observed.

Alignment of ARGs-harboring contigs to nt/NCBI database resulted in matches with different although phylogenetically close taxa (mostly Proteobacteria), including integrons from pathogens like P. aeruginosa and E. coli, and complete genomes of Acidovorax sp. and L. oculi (Table 1). Screening of these genomes with IntegronFinder and HattCI revealed the presence of integron-like features, particularly in L. oculi, in which two integrases and 92 attC sites were predicted by IntegronFinder (e value < 1e−5). Actinobacteria is also a possible host for these integron-cassettes. Although known ARGs-cassettes are frequently associated with Gammaproteobacteria class 1 MIs, integron-cassettes are widely disseminated, and there are evidences that SCIs have been shared among taxa in the same environment for a long period, as reviewed by Escudero et al. [5].

Concerning the bacterial community profile, as expected for freshwater environments, the Velhas River microbiome was largely composed by four phyla: Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes [1, 51], with predominance of Betaproteobacteria. As outlined in the review by Ferro et al. [52], although frequently found in surface waters, Betaproteobacteria harbor both resistance determinants and virulence factors, and have the potential of becoming emergent pathogens.

A significant proportion of Enterococcus-related sequences were observed (Fig. 3). This genus is commonly associated with fecal contamination, although it has been detected in non-contaminated freshwater environments [53]. According to the 2013 report of the Instituto Mineiro de Gestão de Águas [14], the thermotolerant coliforms concentration in a monitoring station upstream the sampling point was above the threshold of 1e3/100 mL, suggesting that the presence of this genus is associated with fecal pollution.

Alpha-diversity measures (Online Resource 4) indicated, in an exploratory way, an influence of seasonality, which might impact ARGs profile as well. The higher alpha-diversity values were observed in March (which had the highest pluviosity, color and turbidity), followed by May and April. It is possible that the more similar conditions between the latter (Online Resource 1) have led to a closer diversity pattern. However, to understand the seasonal impact on environmental gene cassettes, studies with more samples and longer periods are necessary.

In a meta-analysis of the mobile resistome in 23,425 bacterial genomes, the authors found that ARGs are mostly harbored by members of Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria [54], which were represented here by classes hosting ARGs-KOs such as Actinobacteria, Cytophaga, Bacilli, and Betaproteobacteria. In particular, Hydrogenophaga and Ramlibacter genera were the main contributors for KOs potentially related to antibiotic resistance (Fig. 4). Although PICRUSt results are based on phylogeny of close clades and not direct observations, the most abundant KOs possibly related with resistance belonged to the ABC transporter superfamily. These transporters are among the largest and most widespread efflux pumps, and use the energy from ATP hydrolysis to promote the transport of a variety of molecules, from amino acids to antibiotics, including cephalosporins, lincosamides, macrolides, and tetracyclines [55]. It is important to highlight that ARGs found in the integron-cassettes dataset cannot be directly associated with 16S rRNA gene analysis. However, the latter provides information on the bacterial community of the Velhas River and its possible connections with antibiotic resistance.

The results of the present work emphasize the importance of exploring the vast pool of cassettes harbored by environmental integrons, and the possible associations of antibiotic resistance determinants with little studied bacterial taxa. In this way, additional analysis focusing on environmental integrons through amplicon deep-sequencing or shotgun metagenomics can help improving our understanding on the spread of resistance between human settings and the environment. Further recommendations would be to investigate the functionality of the predicted resistance-related ORFs, and to sample over a longer period and at different sampling points.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results showed that cassettes related to antibiotic resistance were not predominant in the studied environment, but included clinically relevant genes (e.g., blaGES5). Two putative novel cassettes homologs to novA and fosB3 were detected. These findings also highlight the predominance of diverse unexplored functions in integron-cassettes, which might confer advantageous adaptations for its hosts under specific conditions, and of possible bacterial hosts in the environment. Altogether, this study reinforces the important role of environmental integrons as source of novel cassettes and expands its understanding beyond clinical settings.

Supplementary information

Physicochemical characterization of water samples (PDF 17.6 kb)

Flow chart of the bioinformatic steps used for integron-cassette amplicons analysis (PDF 81.8 kb)

Additional information about putative integron-cassettes not observed in the INTEGRALL database (XLSX 16.5 kb)

Alpha-diversity metrics of samples collected in March, April, and May (PDF 49 kb)

Acknowledgments

Our acknowledgments to the Companhia de Saneamento de Minas Gerais (COPASA-MG/Brazil) for the Velhas River water samples and the physicochemical data.

Author’s contributions

AMAN and MFD designed the study. MFD and MPR performed sample collection. AMM, MFD, and MPR conducted sample filtering, DNA extraction and quantification; and AOC, MFD, and SF, library preparation. GMC, MFD, MLSS and MSA carried out the bioinformatics analysis. AMAN, MCP and MFD wrote the manuscript. FPL, IH and EK revised the draft.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001, and by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, grant number 306774/2016-0), the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG, grant number APQ-01673-16), and the Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa da UFMG (PRPq). Thanks are due for the financial support to CESAM (UID/AMB/50017/2019), to FCT/MEC through national funds, and the co-funding by the FEDER, within the PT2020 Partnership Agreement and Compete 2020.

Data availability

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI database under the accession number PRJNA432952.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Vaz-Moreira I, Nunes OC, Manaia CM. Bacterial diversity and antibiotic resistance in water habitats: searching the links with the human microbiome. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38:761–778. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouki C, Venieri D, Diamadopoulos E. Detection and fate of antibiotic resistant bacteria in wastewater treatment plants: a review. Ecotox Environ Safe. 2013;91:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grenni P, Ancona V, Barra Caracciolo A. Ecological effects of antibiotics on natural ecosystems: a review. Microchem J. 2018;136:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2017.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stokes HW, Hall RM. A novel family of potentially mobile DNA elements encoding site-specific gene-integration functions: integrons. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1669–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escudero JA, Loot C, Nivina A, Mazel D. The integron: adaptation on demand. In: Craig N, Chandler M, Gellert M, Lambowitz A, Rice P, Sandmeyer S, editors. Mobile DNA III. Washington: ASM Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boucher Y, Labbate M, Koenig JE, Stokes HW. Integrons: mobilizable platforms that promote genetic diversity in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowe-Magnus DA, Guerout A-M, Ploncard P, Dychinco B, Davies J, Mazel D. The evolutionary history of chromosomal super-integrons provides an ancestry for multiresistant integrons. PNAS. 2001;98(2):652–657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cury J, Jové T, Touchon M, Néron B, Rocha EP. Identification and analysis of integrons and cassette arrays in bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:4539–4550. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rapa RA, Labbate M. The function of integron-associated gene cassettes in Vibrio species: the tip of the iceberg. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:385. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An X-L, Chen Q-L, Zhu D, Zhu Y-G, Gillings MR, Su J-Q. Impact of wastewater treatment on the prevalence of integrons and the genetic diversity of integron gene cassettes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84(9):e02766–e02717. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02766-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillings MR. DNA as a pollutant: the clinical class 1 integron. Curr Pollu Rep. 2018;4:49–55. doi: 10.1007/s40726-018-0076-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Razavi M, Marathe NP, Gillings MR, Flach C-F, Kristiansson E, Joakim Larsson DG. Discovery of the fourth mobile sulfonamide resistance gene. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0379-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghaly TM, Geoghegan JL, Alroy J, Gillings MR. High diversity and rapid spatial turnover of integron gene cassettes in soil. Environ Microbiol. 2019;21:1567–1574. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IGAM, Instituto Mineiro de Gestão das Águas (2013) Identificação de municípios com condição crítica para a qualidade de água na bacia do rio das Velhas. http://www.igam.mg.gov.br/images/stories/ARQUIVO_SANEAMENTO/estudo-saneamento-rio-das-velhas.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 2020

- 15.Elsaied H, Stokes HW, Nakamura T, Kitamura K, Fuse H, Maruyama A. Novel and diverse integron integrase genes and integron-like gene cassettes are prevalent in deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2298–2312. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsaied H, Stokes HW, Kitamura K, Kurusu Y, Kamagata Y, Maruyama A. Marine integrons containing novel integrase genes, attachment sites, attI and associated gene cassettes in polluted sediments from Suez and Tokyo Bays. ISME J. 2011;5:1162–1177. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parada AE, Needham DM, Fuhrman JA. Every base matters: assessing small subunit rRNA primers for marine microbiomes with mock communities, time series and global field samples: primers for marine microbiome studies. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:1403–1414. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apprill A, McNally S, Parsons R, Weber L. Minor revision to V4 region SSU rRNA 806R gene primer greatly increases detection of SAR11 bacterioplankton. Aquat Microb Ecol. 2015;75:129–137. doi: 10.3354/ame01753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Cambridge: Babraham Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nurk S, Meleshko D, Korobeynikov A, Pevzner PA. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 2017;27:824–834. doi: 10.1101/gr.213959.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyatt D, Chen G-L, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones P, Binns D, Chang H-Y, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, McWilliam H, Maslen J, Mitchell A, Nuka G, Pesseat S, Quinn AF, Sangrador-Vegas A, Scheremetjew M, Yong SY, Lopez R, Hunter S. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanenbaum DM, Goll J, Murphy S, Kumar P, Zafar N, Thiagarajan M, Madupu R, Davidsen T, Kagan L, Kravitz S, Rusch DB, Yooseph S. The JCVI standard operating procedure for annotating prokaryotic metagenomic shotgun sequencing data. Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;2:229–237. doi: 10.4056/sigs.651139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moura A, Soares M, Pereira C, Leitao N, Henriques I, Correia A. INTEGRALL: a database and search engine for integrons, integrases and gene cassettes. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1096–1098. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altschul SF, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pereira MB, Wallroth M, Kristiansson E, Axelson-Fisk M. HattCI: fast and accurate attC site identification using hidden Markov models. J Comput Biol. 2016;23:891–902. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2016.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen S, Huang T, Zhou Y, Han Y, Xu M, Gu J. AfterQC: automatic filtering, trimming, error removing and quality control for fastq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2017;18(3):80. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1469-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Peña AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald D, Price MN, Goodrich J, Nawrocki EP, DeSantis TZ, Probst A, Andersen GL, Knight R, Hugenholtz P. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2012;6:610–618. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langille MGI, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, McDonald D, Knights D, Reyes JA, Clemente JC, Burkepile DE, Vega Thurber RL, Knight R, Beiko RG, Huttenhower C. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bai H, Lv H, Deng A, Jiang X, Li X, Wen T. Lysobacter oculi sp. nov., isolated from human Meibomian gland secretions. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2020;113:13–20. doi: 10.1007/s10482-019-01289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillings MR. Integrons: past, present, and future. Microbiol Mol Biol Res. 2014;78:257–277. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00056-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliveira-Pinto C, Costa PS, Reis MP, Chartone-Souza E, Nascimento AMA. Diversity of gene cassettes and the abundance of the class 1 integron-integrase gene in sediment polluted by metals. Extremophiles. 2016;20:283–289. doi: 10.1007/s00792-016-0820-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klemm EJ, Wong VK, Dougan G. Emergence of dominant multidrug-resistant bacterial clades: lessons from history and whole-genome sequencing. PNAS. 2018;115(51):12872–12877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717162115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collignon PC, Conly JM, Andremont A, McEwen SA, Aidara-Kane A. World Health Organization ranking of antimicrobials according to their importance in human medicine: a critical step for developing risk management strategies to control antimicrobial resistance from food animal production. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:1087–1093. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma L, Li A-D, Yin X-L, Zhang T. The prevalence of integrons as the carrier of antibiotic resistance genes in natural and man-made environments. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51:5721–5728. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b05887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez-Mozaz S, Chamorro S, Marti E, Huerta B, Gros M, Sànchez-Melsió A, Borrego CM, Barceló D, Balcázar JL. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in hospital and urban wastewaters and their impact on the receiving river. Water Res. 2015;69:234–242. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu L, Ouyang W, Qian Y, Su C, Su J, Chen H. High-throughput profiling of antibiotic resistance genes in drinking water treatment plants and distribution systems. Environ Pollut. 2016;213:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Picão RC, Poirel L, Gales AC, Nordmann P. Diversity of β-lactamases produced by ceftazidime-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates causing bloodstream infections in Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3908–3913. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00453-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Escandón-Vargas K, Reyes S, Gutiérrez S, Villegas MV. The epidemiology of carbapenemases in Latin America and the Caribbean. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2017;15:277–297. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2017.1268918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yerushalmi H, Lebendiker M, Schuldiner S. EmrE, an Escherichia coli 12-kDa multidrug transporter, exchanges toxic cations and H+ and is soluble in organic solvents. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6856–6863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buffet-Bataillon S, Tattevin P, Maillard J-Y, Bonnaure-Mallet M, Jolivet-Gougeon A. Efflux pump induction by quaternary ammonium compounds and fluoroquinolone resistance in bacteria. Future Microbiol. 2015;11:81–92. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wassenaar TM, Ussery D, Nielsen LN, Ingmer H. Review and phylogenetic analysis of qac genes that reduce susceptibility to quaternary ammonium compounds in Staphylococcus species. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp) 2015;5:44–61. doi: 10.1556/EUJMI-D-14-00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu X, Chen C, Lin D, Guo Q, Hu F, Zhu D, Li G, Wang M. The fosfomycin resistance gene fosB3 is located on a transferable, extrachromosomal circular intermediate in clinical Enterococcus faecium isolates. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steffensky M, Mühlenweg A, Wang Z-X, Li S-M, Heide L. Identification of the novobiocin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces spheroides NCIB 11891. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1214–1222. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.5.1214-1222.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fatahi-Bafghi M. Antibiotic resistance genes in the Actinobacteria phylum. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:1599–1624. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03580-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dias MF, Fernandes GR, de Paiva MC, Salim ACM, Santos AB, Nascimento AMA. Exploring the resistome, virulome and microbiome of drinking water in environmental and clinical settings. Water Res. 2020;174:115630. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferro P, Vaz-Moreira I, Manaia CM. Betaproteobacteria are predominant in drinking water: are there reasons for concern? Crit Rev Microbiol. 2019;45:649–667. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2019.1680602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weigand MR, Ashbolt NJ, Konstantinidis KT, Santo Domingo JW. Genome sequencing reveals the environmental origin of enterococci and potential biomarkers for water quality monitoring. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:3707–3714. doi: 10.1021/es4054835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu Y, Yang X, Li J, Lv N, Liu F, Wu J, Lin IYC, Wu N, Weimer BC, Gao GF, Liu Y, Zhu B. The bacterial mobile resistome transfer network connecting the animal and human microbiomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:6672–6681. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01802-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chitsaz M, Brown MH. The role played by drug efflux pumps in bacterial multidrug resistance. Essays Biochem. 2017;61:127–139. doi: 10.1042/EBC20160064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Physicochemical characterization of water samples (PDF 17.6 kb)

Flow chart of the bioinformatic steps used for integron-cassette amplicons analysis (PDF 81.8 kb)

Additional information about putative integron-cassettes not observed in the INTEGRALL database (XLSX 16.5 kb)

Alpha-diversity metrics of samples collected in March, April, and May (PDF 49 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI database under the accession number PRJNA432952.