Abstract

Objectives

Workers at sea have high mortality, injuries and illnesses and work in a hazardous environment compared to ashore workers. The present study was designed to measure the incidence of occupational injuries and diseases among seafarers and quantify the contribution of differences in rank and job onboard on seafarers’ diseases and injuries rates.

Design

Descriptive epidemiological study.

Setting and participants

This study’s data were based on contacts (n=423) for medical requests from Compagnie Maritime d'Affrètement/Compagnie Générale Maritime (CMA-CGM) container ships to the Italian Telemedical Maritime Assistance Service in Rome from 2016 to 2019, supplemented by data on the estimated total at-risk seafarer population on container ships (n=13 475) over the study period.

Outcome measures

Distribution of injuries by anatomic location and types of diseases across seafarers’ ranks and worksites. We determined the incidence rate and incidence rate ratio (IRR) with a 95% CI.

Results

The total disease rate was 25 per 1000 seafarer-years, and the overall injury rate was 6.31 per 1000 seafarer-years over the 4 years study period. Non-officers were more likely than officers to have reported gastrointestinal (IRR 2.12, 95% CI 1.13 to 4.26), dermatological (IRR 3.66, 95% CI 1.27 to 14.42) and musculoskeletal (IRR 2.25, 95% CI 1.11 to 5.05) disorders onboard container ships. Deck workers were more likely than engine workers to be injured in the wrist and hand (IRR 3.25, 95% CI 1.19 to 10.23).

Conclusions

Rates of reported injury and disease were significantly higher among non- officers than officers; thus, this study suggests the need for rank-specific preventative measures. Future studies should consider risk factors for injury and disease among seafarers in order to propose further preventive measures.

Keywords: epidemiology, epidemiology, epidemiology, occupational & industrial medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first study to measure the contribution of differences in rank and job to the rates of injury and disease of seafarer’s onboard container ships.

This study measured the incidence rates and Incidence rate ratios of injury and disease by rank and worksite of seafarers based on contacts from onboard container ships to Telemedical Maritime Assistance Service.

The estimated at-risk seafarer population was used in the analysis due to the lack of information on the actual at-risk seafarer population.

Introduction

In 2015, more than 1.6 million seafarers served worldwide, of which 774 000 and 873 500 were officers and ratings, respectively.1 It is estimated that nearly 65 000 deep-sea merchant ships operate worldwide, carrying more than 1.6 million sailing seafarers.1 2

In general, work onboard ships are broadly grouped by working areas, including the deck, engine and galley.3 Shipping is one of the most widespread transportation systems, and more than 88% of the world’s trade use it.4 5 Workers at sea have high mortality, injuries and diseases rate compared with ashore workers.5 Sailing seafarers have a one in eleven chance of being injured on duty on board,6 and sometimes physical injuries can be acute and a primary cause of disability. Different studies have reported higher mortality and morbidity rates onboard merchant ships when compared with the land occupation. For instance, a study conducted on the British merchant fleet reported that between 2003 and 2012, the fatal accident rate in shipping was 21 times higher than that in the general British workforce, 4.7 times higher than that in the construction industry and 13 times higher than in manufacturing.7 Fatal occupational accidents in Danish seafarers onboard ships were 11.5 times higher than Danish male workers ashore.8 Moreover, seafarers working on board of British merchant ships had 23.9 times higher risk of mortality due to accidents at work than all workers in Great Britain.9 The risk of death is 25 times higher for maritime transport than for air transport, according to the death accounts for every 100 km.10

Identifying the potential area of incidents and assessing the probability of the occurrence of occupational medical events may assure the availability of treatment and the development of prevention strategies to reduce the rate of diseases and/or injuries among seafarers and to improve health outcomes.11–13 Unfortunately, due to the scarcity of evidence-based information on the incidence of occupational diseases and injuries onboard ships, preventive measures in the maritime environment received less attention than other working activities.14 On the other hand, determinants of onboard merchant ship illnesses, injuries, disability and fatalities, remain not adequately studied due to the not easy access of seafarer’s medical data.3 13 15 Previous studies have reported that non-officers have a higher risk for diseases and injuries compared with officers,3 15–18 but most of these studies considered only occupational groups.

The exposure to the work-related risk of officers and non-officers working in different ship areas such as deck, engine and galley is not similar because they attend different duties in different working hours.19 For instance, workers in the engine room are exposed to work-related risks such as noise, vibration and heat or pollutants during their working hours.19 20 In contrast, people working in the deck, as well as in the galley, are potentially exposed to different work-related risks.19 Because of the different areas of activity and associated burdens, the likelihood of illnesses and the occurrence of injuries can differ. Hence, the study on the incidence rates (IR) of injury and disease by rank and worksite of seafarers would provide information for prevention strategies such as resource allocation, prioritising training areas, improving the medicine chests on board, and access to telemedicine consultation to reduce injury and disease at the workplace.

The present study aimed to analyse the IR of reported occupational diseases and injuries among seafarers by worksite and rank groups. This work provides factual information on the rate of diseases and injuries between the worksite group as well as the rank. The results obtained can be used to prioritise occupational health risks and guide the development of preventative measures onboard container ships.

Materials and Methods

Study design, data source and collection procedure

We employed a descriptive epidemiological study and received data from the Centro Internazionale Radio Medico (International Radio Medical Centre, C.I.R.M.) database. C.I.R.M. is the Italian Telemedical Maritime Assistance Service (TMAS) and represents one of the oldest and best known TMAS worldwide. C.I.R.M. operates since 1935 and has assisted more than 100 000 seafarers onboard ships.21 Compagnie Maritime d'Affrètement/Compagnie Générale Maritime (CMA-CGM) is a French container transport and shipping company. It is a leading shipping group globally, using 200 shipping routes between 420 ports in 150 different countries. In this particular study, the data source we used was reported diseases and injuries from onboard CMA CGM container ships to TMAS, in Rome. CMA-CGM made a contractual agreement with C.I.R.M. Spin-off CIRM SERVIZI. In view of this agreement, data provided for medical assistance on the company’s board ships are more detailed and, therefore, can be used for a basic epidemiological analysis.

Work-related diseases are diseases predominantly due to physical, chemical, and biological factors associated with merchant seafaring occupations, and they are recorded in the C.I.R.M. database according to the WHO International Classification of Disease 10th revised version (ICD 10). An occupational injury is defined as a sudden, unexpected and unwanted forceful event due to an external cause’s onboard ships. In the C.I.R.M. database, injuries also are recorded according to the WHO ICD 10th revised version (chapter XIX, S00-S99 and T00-T98).

The classification of both diseases and occupational injuries was made according to the prompt diagnosis and recorded medical datasets in the C.I.R.M. database. The injury and disease rates measured were based on the contacts from onboard container ships to the Italian TMAS in Rome. Any contact for medical requests from ships to the C.I.R.M. with injuries or cases of illness with important patient data, including age, sex, job, rank, the nationality of the patient, ship flag, ship name, date of medical event that occurred, anatomic location of the injury, diagnosis, treatment provided, the patient follow-up schedule and other relevant information are registered in the database. Hence, we got access to occupational injuries and diseases with seafarers' rank and job from the TMAS database for this particular study.

An estimated total number of at-risk seafarer population was calculated by multiplying the number of vessels during the study period by the average number of crew members per vessel. As a result, large ships, including general cargo, tankers and bulk carriers, have an average size of 20 crew members per ship.3 The CMA CGM shipping company handles only container ships, with an average of 25 crew members per ship. Regarding rank distribution per ship, nine officers and sixteen non-officers serve onboard. In respect of worksite, 10 deck workers, thirteen engine workers and two galleys (catering) workers are in service per vessel. The average number of the crew size, their rank as well as worksite distribution per large vessel based on the knowledge of industry norm were calculated.

The number of CMA CGM container ships contracted over 4 years, from January 2016 to 31 December 2019, was 539. In other words, 539 vessels represented the total number of active ships onboard in 4 years (January 2016 to 31 December 2019), and due to this, we determined the cumulative IR. An estimated number of the total at-risk seafarer population for worksite and rank was determined by multiplying the total number of vessels over 4 years by occupation and rank distribution per ship. The total number of seafarers at risk was adjusted proportionally to the number of seafarers in the dataset for whom information on occupation and rank was available.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics such as mean and SD of age, frequency and percentage of injuries by anatomic location and types of diseases were done to evaluate the distribution of reported occupational injuries and diseases in seafarers with injuries and diseases. Rank was stratified by officers (deck and engine officers) and non-officers (deck and engine ratings, and galley). The worksite was also categorised into three groups, including the deck, engine and galley. Then, worksite and rank-specific IR were calculated by dividing the number of cases by the total at-risk seafarer population for each worksite and rank over 4 years. IR ratio (IRR) and 95% CI were calculated to compare the injuries and diseases rates by seafarer’s rank and worksite. The outcome of rates was expressed as per 1000 seafarer-years. Seafarer-year is defined as the number of crew members per ship multiplied by the number of vessels each year. The χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used to determine distributional differences in rank and worksite groups. A two-tailed p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The STATA software V.15 was used for data analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the study.

Results

Overall, 423 patients were assisted by the C.I.R.M. aboard container ships during the 4-year study period. Of these, 338 (80%) and 85 (20%) were diseases and injuries, respectively. However, 11% (37) of the total number of patients with the disease and 8% (7) of the injured patients were unknown as to rank and worksite. The mean age (SD) of seafarers with diseases and injuries was 40.37+12.52 years and 38.39+12.88 years, respectively. Non-officers were more likely than officers to be injured (IRR=1.75) and to have reported the disease (IRR=1.45). Deck workers are almost two times more likely than engine workers to be injured (p<0.004) (table 1).

Table 1.

Number of cases, seafarer-years, incidence rates and incidence rate ratios (IRR) of injury and disease by rank and worksite of seafarers from 2016 to 2019

| Variable | Injury (n=78) | Seafarer-years | Injury incidence rate (95% CI) |

IRR* (95% CI) |

P value |

| Total | 78 | 12 365 | 6.31 (4.98 to 7.86) | N/A | |

| Rank | |||||

| Officer | 19 | 4451 | 4.27 (2.57 to 6.66) | 1 | |

| Non-officer | 59 | 7914 | 7.45 (5.68 to 9.61) | 1.75 (1.02 to 3.10) | 0.029 |

| Worksite | |||||

| Deck | 43 | 4946 | 8.69 (6.29 to 11.69) | 1.99 (1.21 to 3.34) | 0.004 |

| Engine | 28 | 6430 | 4.35 (2.89 to 6.29) | 1 | |

| Galley | 7 | 989 | 7.07 (2.85 to 14.53) | ||

| Disease (n=301) | Seafarer-years | Disease incidence rate (95% CI) |

IRR* (95% CI) |

||

| Total | 301 | 12 000 | 25.00 (22.36 to 28.04) | N/A | |

| Rank | |||||

| Officer | 84 | 4320 | 19.44 (15.54 to 24.02) | 1 | |

| Non-officer | 217 | 7680 | 28.25 (24.66 to 32.21) | 1.45 (1.12 to 1.89) | 0.003 |

| Worksite | |||||

| Deck | 171 | 4800 | 35.63 (30.56 to 41.26) | 2.12 (1.65 to 2.72) | 0.001 |

| Engine | 105 | 6240 | 16.83 (13.78 to 20.33) | 1 | |

| Galley | 25 | 960 | 26.00 (16.92 to 38.20) |

*IRR only reported the result with a significant comparison at p<0.05 for non-officer versus officer, deck versus engine, deck versus galley and engine versus galley.

N/A, not applicable.

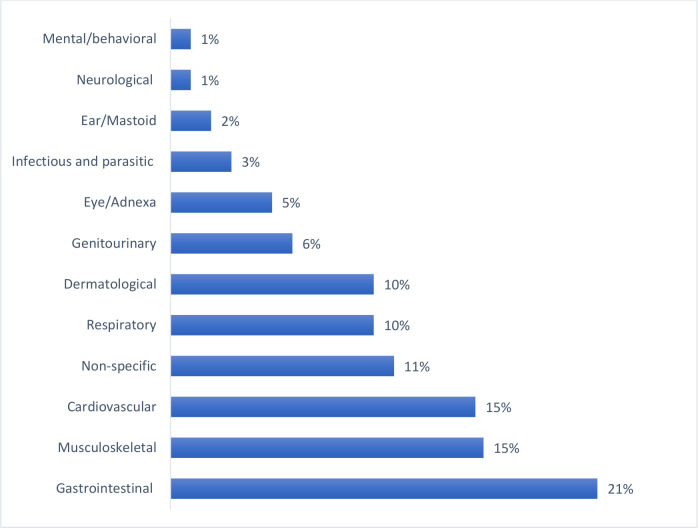

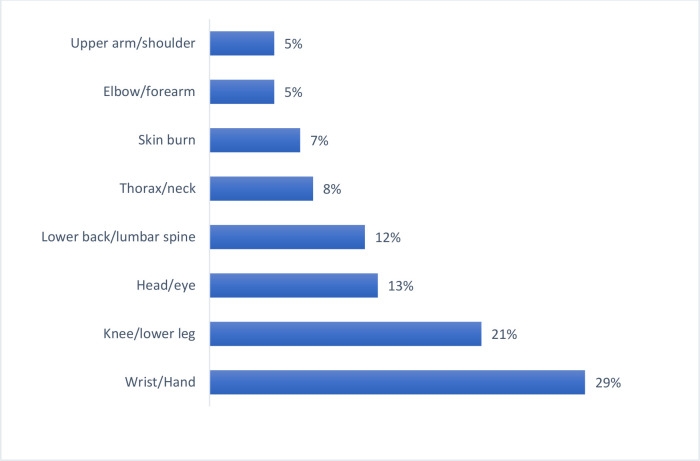

The most frequent causes of illnesses onboard ships were gastrointestinal disorders (n=71, 21%), followed by musculoskeletal (n=52, 15%) and cardiovascular diseases (n=51, 15%) (figure 1). In general, out of the 85 injuries, 29% were wrist and hand injuries, 21% were knee/lower leg injuries, 13% were head/eye injuries, 12% were lower back/lumbar spine injuries, 8% were thorax/neck injuries (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Diagnosis of seafarers according to WHO ICD 10th category from 2016 to 2019 (n=338). ICD-10, International Classification of Disease 10th revised version.

Figure 2.

Distribution of injured body parts of seafarers with injuries from 2016 to 2019 (n=85).

Rank-specific IR of occupational injuries and diseases

Gastrointestinal diseases were the most common disorders for officers (IR=3.07 per 1000 seafarer-years) and non-officers (IR=6.51 per 1000 seafarer-years), as presented in table 2. The most common injuries for non-officer was wrist/hand (1.93 per 1000 seafarer-years) and knee/lower leg (1.84 per 1000 seafarer-years). The IRR for non-officers’ versus officers was determined and reported in table 2. As a result, non-officers were more likely than officers to have gastrointestinal (IRR=2.12), musculoskeletal (IRR=2.25), and dermatological (IRR=3.66) disorders. Concerning injuries, non-officers were more likely than officers to be injured in the knee or lower leg (IRR=4.21) (table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence rate of diseases and occupational injuries by the seafarer rank from 2016 to 2019 (n=379)

| Medical events | Officer | Non-officer | IRR* | 95% CI | P value | ||||

| No | Rate | 95% CI | No | Rate | 95% CI | ||||

| Disease types | |||||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 13 | 3.07 | 1.64 to 5.24 | 49 | 6.51 | 4.82 to 8.59 | 2.12 | 1.13 to 4.26 | 0.011† |

| Musculoskeletal | 10 | 2.14 | 1.03 to 3.94 | 40 | 4.82 | 3.45 to 6.56 | 2.25 | 1.11 to 5.05 | 0.016† |

| Cardiovascular | 10 | 2.69 | 1.29 to 4.95 | 29 | 4.39 | 2.95 to 6.31 | 1.63 | 0.77 to 3.75 | 0.179 |

| Non-specific | 12 | 2.86 | 1.47 to 4.99 | 20 | 2.68 | 1.64 to 4.14 | 0.94 | 0.44 to 2.10 | 0.849 |

| Respiratory | 11 | 2.59 | 1.29 to 4.63 | 17 | 2.25 | 1.31 to 3.60 | 0.87 | 0.38 to 2.05 | 0.711 |

| Dermatological | 4 | 0.88 | 0.24 to 2.25 | 26 | 3.22 | 2.10 to 4.71 | 3.66 | 1.27 to 14.42 | 0.007† |

| Genitourinary | 10 | 2.06 | 0.99 to 3.78 | 11 | 1.27 | 0.64 to 2.28 | 0.62 | 0.24 to 1.63 | 0.280 |

| Eye/adnexa | 6 | 1.31 | 0.48 to 2.86 | 10 | 1.23 | 0.59 to 2.27 | 0.94 | 0.31 to 3.14 | 0.887 |

| Infectious and parasitic | 5 | 1.26 | 0.40 to 2.94 | 4 | 0.57 | 0.15 to 1.45 | 0.45 | 0.09 to 2.09 | 0.250 |

| Ear/Mastoid | 2 | 0.41 | 0.05 to 1.49 | 4 | 0.46 | 0.13 to 1.19 | 1.13 | 0.16 to 12.44 | 0.927 |

| Neurological‡ | — | — | — | 4 | 0.46 | 0.13 to 1.19 | — | — | N/A |

| Mental/behavioural | 1 | 0.21 | 0.005 to 1.14 | 3 | 0.35 | 0.07 to 1.02 | 1.69 | 0.14 to 88.59 | 0.713 |

| Injury location | |||||||||

| Wrist/hand | 8 | 1.72 | 0.74 to 3.38 | 16 | 1.93 | 1.11 to 3.14 | 1.13 | 0.45 to 3.03 | 0.801 |

| Knee/lower leg | 2 | 0.44 | 0.05 to 1.57 | 15 | 1.84 | 1.03 to 3.03 | 4.20 | 1.01 to 38.01 | 0.032† |

| Head/eye | 3 | 0.76 | 0.16 to 2.21 | 6 | 0.85 | 0.31 to 1.85 | 1.13 | 0.24 to 6.95 | 0.898 |

| Lower back/lumbar spine | 3 | 0.77 | 0.16 to 2.25 | 5 | 0.73 | 0.24 to 1.69 | 0.94 | 0.18 to 6.07 | 0.911 |

| Thorax/neck | 1 | 0.21 | 0.005 to 1.14 | 6 | 0.69 | 0.25 to 1.51 | 3.37 | 0.41 to 155 | 0.261 |

| Skin burns | 1 | 0.21 | 0.005 to 1.14 | 5 | 0.58 | 0.19 to 1.35 | 2.81 | 0.31 to 133 | 0.369 |

| Upper arm/shoulder | 1 | 0.27 | 0.006 to 1.53 | 3 | 0.46 | 0.09 to 1.35 | 1.69 | 0.14 to 88.6 | 0.710 |

| Elbow/forearm‡ | — | — | — | 4 | 0.46 | 0.13 to 1.18 | — | — | N/A |

*IRR calculated as the rate of non-officer/rate of officer.

†Significant at *p<0.05.

‡Dashes indicate no case or the rate or the comparison that was not performed.

IRR, incidence rate ratio; N/A, not applicable.

Worksite-specific IR of diseases and occupational injuries

Table 3 summarises the rates of diseases and injuries per seafarer worksite groups. Consequently, gastrointestinal (IR=7.01), cardiovascular (IR=6.06) and musculoskeletal (IR=5.40) diseases were the most common disorders for deck workers. Musculoskeletal disorders (IR=2.52) were the second most common diseases for engine workers. Wrist/hand injuries (IR=2.89) were the most common injury for both deck and galley workers, while knee/lower leg injuries (IR=1.06) were for engine workers (table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence rates of diseases and occupational injuries by seafarer’s worksite from 2016 to 2019 (n=379)

| Medical events | Deck | Engine | Galley | ||||||

| No | Rate | 95% CI | No | Rate | 95% CI | No | Rate | 95% CI | |

| Disease types | |||||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 33 | 7.01 | 4.83 to 9.83 | 23 | 3.76 | 2.38 to 5.63 | 6 | 6.37 | 2.34 to 13.83 |

| Musculoskeletal | 28 | 5.40 | 3.59 to 7.79 | 17 | 2.52 | 1.47 to 4.04 | 5 | 4.82 | 1.56 to 11.22 |

| Cardiovascular | 25 | 6.06 | 3.93 to 8.94 | 10 | 1.86 | 0.89 to 3.43 | 4 | 4.85 | 1.32 to 12.38 |

| Non-specific | 18 | 3.86 | 2.29 to 6.09 | 13 | 2.15 | 1.14 to 3.66 | 1 | 1.07 | 0.03 to 5.96 |

| Respiratory | 18 | 3.82 | 2.26 to 6.02 | 9 | 1.46 | 0.67 to 2.78 | 1 | 1.06 | 0.03 to 5.89 |

| Dermatological | 20 | 3.96 | 2.42 to 6.11 | 6 | 0.91 | 0.34 to 1.98 | 4 | 3.96 | 1.08 to 10.09 |

| Genitourinary | 11 | 2.04 | 1.02 to 3.65 | 9 | 1.28 | 0.59 to 2.43 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.02 to 5.16 |

| Eye/Adnexa | 7 | 1.38 | 0.56 to 2.84 | 8 | 1.21 | 0.52 to 2.39 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.03 to 5.48 |

| Infectious and parasitic* | 5 | 1.13 | 0.37 to 2.64 | 4 | 0.69 | 0.19 to 1.79 | — | — | — |

| Ear/Mastoid | 1 | 0.19 | 0.004 to 1.03 | 4 | 0.57 | 0.16 to 1.46 | 1 | 10.93 | 0.02 to 5.16 |

| Neurological | 2 | 0.37 | 0.05 to 1.34 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.003 to 0.79 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.02 to 5.16 |

| Mental/behavioral* | 3 | 0.56 | 0.12 to 1.62 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.003 to 0.79 | — | — | — |

| Injury location | |||||||||

| Wrist/Hand | 15 | 2.89 | 1.62 to 4.77 | 6 | 0.89 | 0.33 to 1.94 | 3 | 2.89 | 0.59 to 8.45 |

| Knee/lower leg* | 10 | 1.96 | 0.94 to 3.61 | 7 | 1.06 | 0.43 to 2.18 | — | — | — |

| Head/eye | 6 | 1.36 | 0.49 to 2.96 | 2 | 0.35 | 0.04 to 1.26 | 1 | 1.13 | 0.03 to 6.30 |

| Lower back/lumbar spine | 4 | 0.93 | 0.25 to 2.37 | 3 | 0.54 | 0.11 to 1.56 | 1 | 1.16 | 0.03 to 6.44 |

| Thorax/neck* | 3 | 0.56 | 0.11 to 1.63 | 4 | 0.57 | 0.16 to 1.46 | — | — | — |

| Skin burns | 1 | 0.19 | 0.004 to 1.03 | 4 | 0.57 | 0.16 to 1.46 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.02 to 5.16 |

| Upper arm/shoulder* | 1 | 0.25 | 0.006 to 1.38 | 2 | 0.38 | 0.05 to 1.37 | — | — | — |

| Elbow/forearm* | 3 | 0.56 | 0.11 to 1.63 | — | — | — | 1 | 0.93 | 0.02 to 5.16 |

*Dashes indicate no case or the rate that was not performed.

The IRRs for deck workers vs engine workers', deck workers vs galley workers', and engine workers versus galley workers were calculated and presented in table 4. As a result, deck workers were more likely than engine workers to have reported gastrointestinal (IRR=1.86), cardiovascular (IRR=3.26), dermatological (IRR=4.35), respiratory (IRR=2.62) and musculoskeletal (IRR=2.14) disorders. Also, deck workers were more likely than engine workers to be injured in the wrist and hand (IRR=3.25)(table 4).

Table 4.

Incidence rate ratios (IRR) and 95% CI of diseases and occupational injuries stratified by seafarers’ worksite from 2016 to 2019 (n=379)

| Medical events | Deck versus engine | Deck versus galley | Engine versus galley | ||||||

| IRR | 95% CI | P value | IRR | 95% CI | P value | IRR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Disease types | |||||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 1.86 | 1.06 to 3.33 | 0.021* | 1.09 | 0.45 to 3.21 | 0.869 | 0.59 | 0.23 to 1.77 | 0.263 |

| Musculoskeletal | 2.14 | 1.13 to 4.17 | 0.013* | 1.12 | 0.43 to 3.72 | 0.857 | 0.52 | 0.19 to 1.81 | 0.224 |

| Cardiovascular | 3.26 | 1.51 to 7.58 | 0.001* | 1.25 | 0.43 to 4.94 | 0.721 | 0.39 | 0.11 to 1.68 | 0.135 |

| Non-specific | 1.80 | 0.83 to 3.99 | 0.108 | 3.59 | 0.57 to 149 | 0.182 | 1.99 | 0.30 to 84.9 | 0.561 |

| Respiratory | 2.62 | 1.11 to 6.57 | 0.017* | 3.59 | 0.56 to 149 | 0.182 | 1.38 | 0.19 to 60.7 | 0.846 |

| Dermatological | 4.35 | 1.68 to 13.18 | 0.001* | 1.00 | 0.34 to 4.03 | 1.044 | 0.23 | 0.05 to 1.11 | 0.053 |

| Genitourinary | 1.59 | 0.59 to 4.34 | 0.311 | 2.20 | 0.31 to 94 | 0.494 | 1.38 | 0.19 to 60.68 | 0.846 |

| Eye/adnexa | 1.14 | 0.35 to 3.59 | 0.803 | 1.40 | 0.18 to 63 | 0.837 | 1.23 | 0.17 to 55 | 0.933 |

| Infectious and parasitic† | 1.63 | 0.35 to 8.19 | 0.486 | — | — | N/A | — | — | N/A |

| Ear/mastoid | 0.32 | 0.006 to 3.28 | 0.337 | 0.20 | 0.002 to 15.6 | 0.333 | 0.61 | 0.06 to 30.30 | 0.646 |

| Neurological | 2.60 | 0.14 to 153 | 0.485 | 0.40 | 0.02 to 23.5 | 0.495 | 0.15 | 0.001 to 12 | 0.267 |

| Mental/behavioral† | 3.90 | 0.31 to 204 | 0.257 | — | — | N/A | — | — | N/A |

| Injury Location | |||||||||

| Wrist/hand | 3.25 | 1.19 to 10.23 | 0.012* | 1.00 | 0.28 to 5.39 | 1.050 | 0.31 | 0.06 to 1.90 | 0.130 |

| Knee/lower leg† | 1.86 | 0.64 to 5.75 | 0.216 | — | — | N/A | — | — | N/A |

| Head/eye | 3.90 | 0.69 to 39.50 | 0.089 | 1.20 | 0.15 to 55 | 0.949 | 0.31 | 0.02 to 18 | 0.398 |

| Lower back/lumbar spine | 1.73 | 0.29 to 11.80 | 0.494 | 0.80 | 0.08 to 39.7 | 0.794 | 0.46 | 0.04 to 24 | 0.524 |

| Thorax/neck† | 0.98 | 0.14 to 5.76 | 0.987 | — | — | N/A | — | — | N/A |

| Skin burns | 0.33 | 0.01 to 3.28 | 0.337 | 0.20 | 0.003 to 15.7 | 0.333 | 0.62 | 0.06 to 30.30 | 0.646 |

| Upper arm/shoulder† | 0.65 | 0.01 to 12.50 | 0.778 | — | — | N/A | — | — | N/A |

| Elbow/forearm† | — | — | N/A | 0.60 | 0.05 to 31.5 | 0.649 | — | — | N/A |

*Significant at p<0.05.

†Dashes indicate the comparison that was not performed.

N/A, not applicable.

Discussion

This descriptive epidemiological study was mainly designed to quantify the IR of reported injuries and diseases among seafarers by worksite and rank groups. We have found that the rates of overall reported diseases were four times higher than the corresponding total reported injuries rates across all worksites. A similar finding was reported from a study conducted in the USA,15 which reported 2–3 times total illnesses higher in the worksites than overall injuries. The overall reported disease rate was 25 per 1000 seafarer-year during the study period. The disease rate for non-officers and officers were significantly differed (IRR 1.45, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.89). This study reported that the most common causes of illnesses on board were gastrointestinal (21%), musculoskeletal (15%) and cardiovascular disorders (15%). Similar findings were reported in a Japanese study,22 which has shown that gastrointestinal (35.5%), musculoskeletal (19.6%) and cardiovascular diseases (11.6%) were the diseases more often occurring onboard ships. Our findings are not consistent with the study conducted in the USA,3 which reported that dental (26%), respiratory (19%), and dermatological (14%) disorders were in the order the illnesses occurring most often among sailing seafarers.

The majority of gastrointestinal (63%) cases were gastro-oesophageal reflux, oesophagitis, ulcers, gastritis, hernia and appendicitis. Our work has demonstrated that non-officers were more likely than officers to have gastrointestinal (IRR=2.12), musculoskeletal (IRR=2.25) and dermatological (IRR=3.66) disorders. This study also revealed that deck workers were more likely than engine workers to have gastrointestinal (IRR=1.86), dermatological (IRR=4.35), respiratory (IRR=2.62) and musculoskeletal (IRR=2.14) disorders. These might be due to work-related stress because maritime officers, including the captain, have high-level responsibilities such as navigation, planning, organisation of loading and unloading operations and ship controls.19 23 Non-officers are involved in other tasks occurring during a voyage and their work is physically more demanding and stressful than officers. In general, seafarers have high work-related stressors when compared with ashore workers20 because their work is characterised by long working hours, often time-pressure, prolonged isolation from family and hectic activity. Various studies have reported that work-related stress has long been considered a contributing factor in the development of musculoskeletal problems24 and gastrointestinal disorders.25 Similarly, as for dermatological disorders, it might result in skin exposure to risk factors in the workplace. Seafaring is a risky activity characterised by exposure to different skin risk factors such as seawater, humidity, solar radiation and others.26 27 Deck crews are frequently engaged in maintenance, repair, loading, painting activities and exposure to chemicals, UV radiation and other skin risk factors.28 29 This study also reported the same rate of dermatological disorders for the deck (IR=3.96) and galley (IR=3.96) workers. However, this could be due to the small number of cases among galley workers, and even the estimated non-cases of galley workers are not comparable in number to deck workers’ non-cases. Consequently, 95% of the CI was wider for the case rate among the galley workers. The IRR results in the comparison made between the workers on deck and in the galley were also not statistically significant (p=1.044) on this matter. Further studies are needed to measure the effect of differences in the workplace of deck and galley workers on dermatological disease rates.

Angina pectoris (39% of all CVD diagnoses) was the most frequently reported cardiovascular disorders in this study. As for cardiovascular disorders, it could be related to lifestyle, especially a high-fat diet, drinking, smoking and physical inactivity. A study conducted on the board of Italian flagship (2019) reported that more than 40% and 10% of seafarers were overweight and obese, respectively.30 This finding suggests that in seafarer’s CVD risk factors are higher compared with ashore workers. We found that cardiovascular (IR=6.06) disorders were the second most common diseases for deck workers and deck workers were also more likely than engine worker to have reported cardiovascular diseases (IRR=3.26). This might be due to work-related stress because deck workers have high work-related stress due to sleep interruption, high job demands, night shift work and intense activity than engine workers. A study reported that work related stress was a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.31 Long working hours are contributing factors to work-related stress, and it is logical to expect an association between long hours and cardiovascular disorders.32 33 Studies have also shown that night shift work had adverse effects on health and risk factors for the development of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases.19 34 35 The relationship between stress and coronary heart disease are considered to be linked to multiple and protracted increases in heart rate and blood pressure resulting from neuroendocrine activation.36–39 Other studies have reported that work-related stress can increase the cardiovascular risk of workers.40–42 On the other hand, cardiovascular diseases and metabolic disorders are stress-related diseases.43

The total reported injury rate was 6.31 per 1000 seafarer-year over 4 years study period. The injury rate for non-officers and officers were significantly differed (IRR 1.75, 95% CI 1.02 to 3.10). Nearly 30% of injuries occurred in the wrist and hand, followed by the knee and lower leg (21%). Our results agree with the study conducted in the Danish-flagged merchant fleet,18 which reported 36% and 18% of upper and lower limb injuries, respectively. Moreover, this study revealed that non-officers were more likely than officers to be injured (IRR=1.75). This finding was in agreement with the previous studies.3 17 44 Non-officer work is characterised by mooring, cleaning the ship, repairing broken cables and ropes, operating machinery such as cranes and drilling towers, and steering the ship at sea.20 23 The non-officer work is also physically challenging19 20 23 and must be carried out regardless of weather conditions. This could explain why non-officers have a higher rate of injuries than officers.

The present study has shown that the deck workers had higher rates of overall reported injuries (IR=8.69) compared with the engine (IR=4.35) workers. These results are consistent with those of the study conducted in the USA.15 We also found the injury rate for deck workers and engine workers were significantly differed (IRR 1.99, 95% CI 1.21 to 3.34). Similarly, deck workers were more likely than engine workers to be injured in the wrist and hand (IRR=3.25), as shown in table 4. A study conducted in Danish Fleet seafarers44 reported that deck workers had a relatively low risk for injuries compared with machine (engine) workers. The difference could be due to methodological differences. The study on seafarers in the Danish fleet was a questionnaire-based survey. Furthermore, denominators, used to determine IR and IRR in the Danish fleet, were not consistent with our study. Deck workers, particularly deck ratings, perform physical works such as mooring and unmooring the ship, loading, and unloading cargo.23 Moreover, deck workers have a shorter sleeping time and sleep interruptions more often than engine workers because they are engaged in the surveillance system with frequent irregular operations. These include monitoring the bridge or gangway, acting as lookouts on the bridge, or carrying out repairs and maintenance work in the deck area.19 20 23 Hence, night shift work, long working hours, short average sleep time and physical stress are important factors contributing to the high rates of injuries/accidents at sea.10 19 45 46

Strengths and limitations

This study measured the IR of reported injury and disease to TMAS for container ships. Most of the previous studies on diseases and injuries among seafarers were focused on the number of cases. As far as we know, this study is the first study to measure the contribution of differences in rank and job to the rates of injury and disease of seafarers onboard container ships. Limitations of this study are: (1) We used an estimated average number of seafarers per ship in the analysis, although we took into account different assumptions, including the number of vessels, ships active at sea, number of crew members per ship and the length of stay of seafarers on board for the accuracy of the estimate. Consequently, the IR may be underestimated or overestimated. (2) Data from patients with injuries and cases of disease contained descriptions such as age and gender, but we had no descriptions of these data on the total at-risk seafarer population. Hence, we have not determined the rates and IRR of the diseases and injuries by seafarers’ age and sex. (3) Patient data on both injury and diagnosis were compiled according to the revised WHO ICD10 codes and the injury’s anatomic location in the database, but not on mechanisms of injury or potential physical hazards related to injured cases. As a result, we have not stratified injuries by mechanisms of injury or occupational hazards to highlight priority areas and recommend preventative measures. (4) We did not have descriptions of data types such as socio-demographic variables and another exposure status of the total seafarer population at risk. In this respect, we have not determined the risk factors for injury and disease to propose further prevention strategies. Furthermore, this study is a retrospective study and limited to the variables available in the dataset. Finally, our study is limited to container ships and does not represent other types of ships at sea. Hence, the results do not reflect seafarers working on other types of ships.

Conclusion

The results of this study were based on the medical events (diseases and occupational injuries) of seafarers while working on board container ships. Non-officers had significantly higher rates of reported gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal and dermatological disorders compared with officers. Also, non-officers were more likely than officers to be injured in the knee and lower leg. Deck workers had significantly higher rates for dermatological, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders when compared with engine workers. Deck workers were more likely than engine workers to be injured in the wrist and hand. In general, the total reported injury and disease rates for non-officers were significantly higher compared with officers. The same is true for deck workers compared with engine workers. Hence, this study suggests the need for rank and work site-specific prevention strategies to reduce injury and disease rates at the workplace. Future studies should consider the risk factors for injury and disease among seafarers in order to propose further preventive measures.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @GetuGamo1

Contributors: GGS: conceived and designed the study, performed analysis, methodology, interpreted the data and results, and drafted the initial manuscript. MD: extracted data and assisted with the preparation of the manuscript. GB: contributed to the data collection. MAS: interpreted the data and involved in the preparation of the manuscript. FA: guided, edited, reviewed and approved the study. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the International Transport Workers Federation (ITF) Trust, London, UK, under grant number 558 to C.I.R.M. Institutional funding of the University of Camerino, Italy, supported Ph.D. bursaries to GGS and GB.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study has been reviewed and approved by the Scientific/Ethics Committee of the C.I.R.M. Foundation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1.BIMCO, ICS . "Manpower Report-The global supply and demand for seafarers, 2015Exec Summ. Available: http://www.ics-shipping.org/docs/default-source/resources/safety-security-and-operations/manpower-report-2015-executive-summary.pdf?sfvrsn=16 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Telemedicine: revolutionising healthcare for seafarers. Available: https://www.ship-technology.com/features/featuretelemedicine-revolutionising-healthcare-for-seafarers-5673476/ [Accessed 10 Aug 2019].

- 3.Lefkowitz RY, Slade MD, Redlich CA. Injury, illness, and disability risk in American seafarers. Am J Ind Med 2018;61:120–9. 10.1002/ajim.22802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IMO (International Maritime Organization). Available: https://business.un.org/en/entities/13 [Accessed 12 Oct 2019].

- 5.Center for maritime safety and health studies, 2019. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/programs/cmshs/port_operations.html [Accessed 12 Oct 2019].

- 6.Mulić R, Vidan P. Comparative analysis of medical assistance to seafarers in the world and the Republic of Croatia. Int Conf Transp Sci 2012:1–8 https://bib.irb.hr/datoteka/587264.Mulic_Vidan_Bosnjak.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts SE, Nielsen D, Kotłowski A, et al. Fatal accidents and injuries among Merchant seafarers worldwide. Occup Med 2014;64:259–66. 10.1093/occmed/kqu017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borch DF, Hansen HL, Burr H, et al. Surveillance of maritime deaths on board Danish merchant ships, 1986-2009. Int Marit Health 2012;63:7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts SE, Hansen HL. An analysis of the causes of mortality among seafarers in the British Merchant Fleet (1986-1995) and recommendations for their reduction. Occup Med 2002;52:195–202. 10.1093/occmed/52.4.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berg HP. Human factors and safety culture in maritime safety (revised). TransNav 2013;7:343–52. 10.12716/1001.07.03.04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter T. Mapping the knowledge base for maritime health: 1 historical perspective. Int Marit Health 2011;62:210–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter T. Mapping the knowledge base for maritime health: 2. a framework for analysis. Int Marit Health 2011;62:217–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter T. Mapping the knowledge base for maritime health: 3 illness and injury in seafarers. Int Marit Health 2011;62:224–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter T. Mapping the knowledge base for maritime health: 4 safety and performance at sea. Int Marit Health 2011;62:236–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefkowitz RY, Slade MD, Redlich CA. "Injury, illness, and work restriction in merchant seafarers". Am J Ind Med 2015;58:688–96. 10.1002/ajim.22459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen HL, Tüchsen F, Hannerz H. Hospitalisations among seafarers on merchant ships. Occup Environ Med 2005;62:145–50. 10.1136/oem.2004.014779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaerlev L, Jensen A, Nielsen PS, et al. Hospital contacts for injuries and musculoskeletal diseases among seamen and fishermen: a population-based cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008;9:1–9. 10.1186/1471-2474-9-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herttua K, Gerdøe-Kristensen S, Vork JC, et al. Age and nationality in relation to injuries at sea among officers and non-officers: a study based on contacts from ships to telemedical assistance service in Denmark. BMJ Open 2019;9:e034502–7. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oldenburg M, Jensen H-J. Stress and strain among Seafarers related to the occupational groups. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:1153. 10.3390/ijerph16071153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oldenburg M, Jensen H-J, Latza U, et al. Seafaring stressors aboard merchant and passenger ships. Int J Public Health 2009;54:96–105. 10.1007/s00038-009-7067-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahdi SS, Amenta F. Eighty years of CIRM. A journey of commitment and dedication in providing maritime medical assistance. Int Marit Health 2016;67:187–95. 10.5603/IMH.2016.0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ehara M, Muramatsu S, Sano Y, et al. The tendency of diseases among seamen during the last fifteen years in Japan. Ind Health 2006;44:155–60. 10.2486/indhealth.44.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.STCW, IMO . International convention on standards of training, certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers. Available: http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/humanelement/trainingcertification/pages/stcw-convention.aspx

- 24.Leino P. Symptoms of stress predict musculoskeletal disorders. J Epidemiol Community Health 1989;43:293–300. 10.1136/jech.43.3.293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim S-K, Yoo SJ, Koo DL, et al. Stress and sleep quality in doctors working on-call shifts are associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:3330–7. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i18.3330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caruso G. Do seafarers have sunshine. 8th International Symposium on Maritime Health (ISMH) Book of abstracts, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laraqui O, Manar N, Laraqui S, et al. Prevalence of skin diseases amongst Moroccan fishermen. Int Marit Health 2018;69:22–7. 10.5603/IMH.2018.0004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer G, Siekmann H, Feister U. Measurement of sunlight exposure in seafaring [determination of natural UV radiation exposure in seafaring]. 50th annual meeting of the German Society for Occupational and Environmental Medicine (DGAUM), 2010:434–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oldenburg M, Kuechmeister B, Ohnemus U, et al. Extrinsic skin ageing symptoms in seafarers subject to high work-related exposure to UV radiation. Eur J Dermatol 2013;23:663–70. 10.1684/ejd.2013.2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nittari G, Tomassoni D, Di Canio M, et al. Overweight among seafarers working on board merchant ships. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1–8. 10.1186/s12889-018-6377-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kivimäki M, Kawachi I. Work stress as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2015;17:630. 10.1007/s11886-015-0630-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Virtanen M, Heikkilä K, Jokela M, et al. Long working hours and coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2012;176:586–96. 10.1093/aje/kws139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin K-S, Chung YK, Kwon Y-J, et al. The effect of long working hours on cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease; a case-crossover study. Am J Ind Med 2017;60:753–61. 10.1002/ajim.22688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boivin DB, Boudreau P. Impacts of shift work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathol Biol 2014;62:292–301. 10.1016/j.patbio.2014.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermansson J, Hallqvist J, Karlsson B, et al. Shift work, parental cardiovascular disease and myocardial infarction in males. Occup Med 2018;68:120–5. 10.1093/occmed/kqy008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:360–70. 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, Zhang M, Loerbroks A, et al. Work stress and the risk of recurrent coronary heart disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2015;28:8–19. 10.2478/s13382-014-0303-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dragano N, Siegrist J, Nyberg ST, et al. Effort-Reward imbalance at work and incident coronary heart disease: a Multicohort study of 90,164 individuals. Epidemiology 2017;28:619–26. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sara JD, Prasad M, Eleid MF, et al. Association between work-related stress and coronary heart disease: a review of prospective studies through the job strain, effort-reward balance, and organizational justice models. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:1–15. 10.1161/JAHA.117.008073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, et al. Work stress in the etiology of coronary heart disease--a meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32:431–42. 10.5271/sjweh.1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaremin B, Kotulak E. Myocardial infarction (MI) at the work-site among Polish seafarers. the risk and the impact of occupational factors. Int Marit Health 2003;54:26–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Filikowski J, Rzepiak M, Renke W, et al. Selected risk factors of ischemic heart disease in Polish seafarers. preliminary report. Int Marit Health 2003;54:40–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siegrist J, Rödel A. Work stress and health risk behavior. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32:473–81. 10.5271/sjweh.1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen OC, Sørensen JF, Canals ML. Incidence of self-reported occupational injuries in seafaring — an international study. Occup Med 2004;54:548–55. 10.1093/occmed/kqh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrington JM. Health effects of shift work and extended hours of work. Occup Environ Med 2001;58:68–72. 10.1136/oem.58.1.68 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spurgeon A, Harrington JM, Cooper CL. Health and safety problems associated with long working hours: a review of the current position. Occup Environ Med 1997;54:367–75. 10.1136/oem.54.6.367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.