Abstract

Older adults have gained great media attention during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they were believed to be vulnerable to the novel virus based on clinical data and epidemiological evidence. The high volume of media coverage played an important role in calling for improved public health services for the older population. Nevertheless, problematic media representations of older people might evoke or amplify ageism during the pandemic. Therefore, drawing on empirical data collected from five mainstream Chinese media outlets between January 3 and May 3, 2020, this study examined how the media constructed the vulnerability of older adults and its underlying ageist thinking during the pandemic. The findings showed that the media had clear preferences in constructing older people as passive recipients while seeking resources from families, public institutions and governments at various levels to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, the media adopted a biomedical-centred framework presenting older people as a homogenous group that was vulnerable to the pandemic. In addition, we found that the media representations of older adults intensified the dichotomised relationship between the young and the old, causing the younger generations to perceive older people as a ‘threat’ to public health. Moving beyond the Chinese case, this article appeals to the media to be socially responsible by avoiding the stereotyping of the older population and uniting the whole society to combat COVID-19. The findings of this study will help raise awareness among policymakers and care service providers, which is crucial to eliminating ageist attitudes across society and to further allowing the values of older individuals to be fully recognised.

Keywords: COVID-19, Older people, Media representation, Vulnerability, Ageism, China

Introduction

The novel coronavirus has spread worldwide, with the number of new confirmed cases increasing continually since its outbreak in Wuhan, China. As of February 6, 2021, the number of people infected was over 105 million across 192 countries, and the death toll had reached 2.3 million and counting (Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect every aspect of human life, and its long-term effects are of great concern to all walks of life.

Since the start of the outbreak, statistics and epidemiological findings on COVID-19 have shown a positive link between old age and the severity of the virus (Kang and Jung 2020; Sominsky et al. 2020; Wu and McGoogan 2020), contributing to the public impression that older people are especially vulnerable to the coronavirus. Consequently, the keyword pair COVID-19 and older people has attracted great attention from the media and thus entered the public eye.

In the context of China, two additional reasons have accounted for the massive attention that older people received from COVID-19 media reporting. First, respecting and caring for older individuals as part of the Confucian doctrine are deeply rooted in Chinese culture (Cheung and Kwan 2012). Hence, shielding older people from the risks of the coronavirus was one of the widely acknowledged priorities in controlling the pandemic. Second, as official guidelines have stated, the life of every Chinese citizen matters and should receive equal treatment if infected with COVID-19. Older people who were statistically and clinically at the highest fatality risks and subsequently required relatively more medical resources were bound to attract mounting media attention.

The high volume of media attention given to the aged population helped raise public health authorities’ awareness of the perceived vulnerability of older adults and to improve their services accordingly. Nevertheless, the media has received extensive criticism for propagating ageist stereotypes and negative attitudes towards older adults in the pandemic and undermining intergenerational solidarity (Ayalon et al. 2020; Fraser 2020; Kessler and Bowen 2020). The assumption underlying the media narratives that all older adults were vulnerable to COVID-19 could be problematic and increase the risk of propagating ageist discourses in society. However, little empirical research has been conducted to demonstrate how ageist stereotypes have been constructed by the media. To address this gap, we take the case of the Chinese news media to investigate how the media represents older people’s vulnerability in COVID-19 news reports and its implications for understanding ageism in public health crises.

Vulnerability, ageism and media representations of older people

Ageism is defined as stereotypes, prejudice or discrimination against (but also in favour of) people due to their chronological age (Ayalon and Tesch-Römer 2017). This usually constructs a negative image of older adults as frail, infirm, unproductive and dependent and as burdens to society (Fealy et al. 2012; Martin et al. 2009).

The media has long been criticised for reinforcing ageist perceptions by spreading the stereotypical negative image of older people (Fealy et al. 2012; Koskinen et al. 2014). Biased media representations of older adults were found to be similar across countries, portraying the older population through a biomedical lens with specific emphasis on old age and physical dependency (Phelan 2018; Wilińska and Cedersund 2010; Zhang and Harwood 2004). In the particular case of the Chinese media, vulnerability is more likely to be portrayed as problem-oriented and age-marked (Chen 2015). Therefore, studying media representations of older people’s vulnerability in China provides a key entry point to understand ageism in the context of the pandemic.

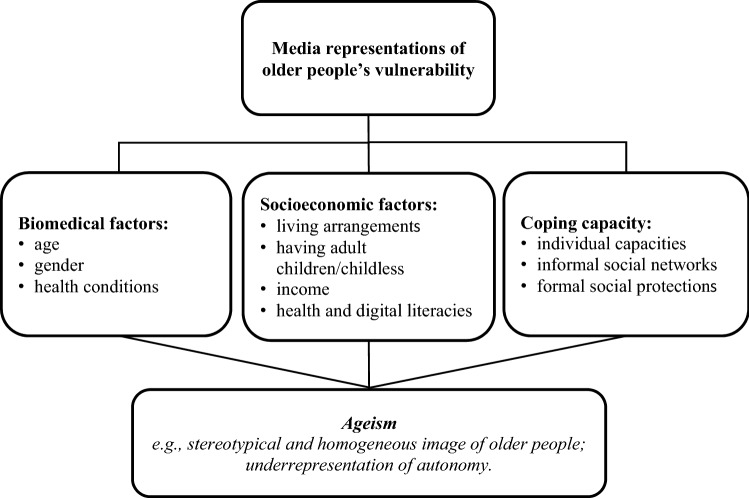

According to Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti (2006), vulnerability in old age is the outcome of complex interactions between older people’s exposures to risks and their coping capacities of averting serious harm. Risks usually relate to a range of biomedical and social factors, including age, gender, health and autonomy, income, living arrangements, and family and social ties (Brocklehurst and Laurenson 2008; Grundy 2006; Pritchard-Jones 2016; Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti 2006). Older adults’ coping capacity is determined by their individual attributes (i.e. wealth, education, skills), which are closely related to their biomedical and socio-economic status. The ability of older people to cope also depends on how they utilise their informal social networks (i.e. family, friends, neighbours) and formal social protections (i.e. pension, health and social services) (Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti 2006).

Inspired by Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti’s work (2006), we developed an analytical framework to examine media representations of the vulnerability of older people during the COVID-19 pandemic. As shown in Fig. 1, we listed a variety of ‘biomedical factors’ and ‘socio-economic factors’ to identify ‘vulnerable’ older adults represented by Chinese media. Health and digital literacies that were deemed crucial to living through COVID-19 were also included in the framework (Calderón-Larrañaga et al. 2020). We then listed the indicators of ‘coping capacity’ to analyse the media-portrayed responses of older people to the pandemic.

Fig. 1.

An analytical framework of ageism in media representations of older people’s vulnerability

In addition, we added ageism to the existing framework to help disclose the prevalent hidden ageist attitudes towards older people through the lens of vulnerability. On the one hand, stereotypical perceptions of older people’s vulnerability, both biomedically (i.e. frail, weak, susceptible, incapable) and socio-economically (i.e. illiterate, dependent, nonautonomous), constitute ageism. On the other hand, ageist attitudes towards older people, such as neglecting their autonomy and categorising them as a homogeneous-dependent group, also reinforce and proliferate the negative images and perceptions that all older people are vulnerable (Ayalon et al. 2020; Jones and Powell 2006).

Guided by the analytical framework, we attempted to answer three research questions through the analysis of the collected news articles from five mainstream Chinese media published between January 3 and May 3, 2020.

- RQ1

What specific groups of older people have been represented as vulnerable in pandemic reporting?

- RQ2

How has the media positioned older people in terms of responding to the pandemic?

- RQ3

How do media representations of vulnerability in old age help reinforce ageism?

Methods

This research combined quantitative and qualitative content analysis. Content analysis, as Bryman (2008) suggested, is a hybrid technique that links quantitative and qualitative methods in analysing textual data in empirical research. On the one hand, the quantitative approach helped systematically classify and distil large amounts of descriptive data into condensed quantified categories of its specific features (Bauer 2000), which allowed us to discover the typical patterns of media representations of older people with respect to vulnerability. On the other hand, the qualitative approach provided us with a means of exploring the themes underlying the textual data (Bauer 2000; Messner et al. 1993), thus enabling us to uncover the ageist thinking behind the media representations of older people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data collection

We chose five popular Chinese media outlets as research sites for data collection, namely China Central Television (CCTV), Xinhua Net, The Paper, Caixin and Southern Weekly. They are all mainstream media that enjoy national circulation and are well known for their investigative journalism. More importantly, they sent task forces to the front line to cover the pandemic.

With a specific focus on the first wave of COVID-19 in China, this research collected news articles published between January 3 and May 3, 2020. We utilised built-in advanced search tools available on the websites of the five chosen media outlets to screen and collect COVID-19 news items involving older adults. A variety of keywords were adopted in the search process, including laoren, laonianren (older people),1zhangzhe (senior), huliyuan (care home), yanglaoyuan (nursing home), xinguan yiqing (COVID-19, coronavirus) and daliuxing (pandemic, epidemic). We did not include brief breaking news or nontextual forms of news in the database, ensuring that rich information was captured for the following content analysis. Based on the above sampling strategies, the researchers selected 568 articles of various types, including news articles, commentaries, feature stories and opinion pieces. All the collected data were then imported into NVivo 12 for coding and further analysis.

Quantitative content analysis

This research first used quantitative content analysis to systematically quantify the collected news content by using predetermined categories (Bryman 2008). The generation of predetermined categories was informed by the analytical framework of ageism in the media representation of older people’s vulnerability (Fig. 1). Multiple categories and subcategories were created for each of the factors. For example, in the case of living arrangements under the theme of socio-economic factors, we developed four subcategories to help classify older adults in the news: living in aged-care facilities, living in private dwellings, living alone or with spouse only and unspecified. The systematic categorisation of specific traits that were being used to characterise older people was crucial to understanding the media bias in representing older people in the COVID-19 pandemic and hence to answer RQ1 and RQ2.

The first author and two research assistants conducted a pilot analysis of 50 randomly selected articles to test the designed categories that constituted the coding scheme after being cross-checked with the second author. Along with the final coding scheme development, modifications were undertaken to ensure that both the main categories and subcategories were able to comprehensively reflect how media represented the traits of older adults in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 1 shows the final coding scheme.

Table 1.

Final content analysis coding scheme

| Theme | Category | Subcategory |

|---|---|---|

| Biomedical factors | Age | 1 = 60–69; 2 = 70–79; 3 = 80 and above; 4 = unspecified |

| Gender | 1 = male; 2 = female; 3 = unspecified | |

| Health conditions | 1 = COVID-19 patient; 2 = non-COVID-19 patients with chronic conditions; | |

| 3 = frail (physically and psychologically); 4 = disabled; 5 = healthy; | ||

| 6 = unspecified | ||

| Socio-economic factors | Source of income | 1 = pension; 2 = social benefits (means-tested, age-related, etc.); |

| 3 = paid work; 4 = others; 5 = unspecified | ||

| Health literacy | 1 = high; 2 = low; 3 = unspecified | |

| Digital literacy | 1 = high; 2 = low; 3 = unspecified | |

| Living arrangements | 1 = living in aged-care facilities; 2 = living in private dwellings; | |

| 3 = living alone or with spouse only; 4 = unspecified | ||

| Children | 1 = having child(ren); 2 = childless; 3 = unspecified | |

| Coping capacity | Sources of support (received) | 1 = immediate family members; 2 = kin, friends, neighbours, etc.; |

| 3 = government at all levels; | ||

| 4 = public institutions and NGOs; 5 = unspecified | ||

| Types of support (received) | 1 = instrumental support (financial, goods, services, etc.); | |

| 2 = informational support (knowledge or advice); | ||

| 3 = emotional care (affection from others, sharing feelings, etc.); | ||

| 4 = unspecified | ||

| Types of support (provide)a | 1 = instrumental support (financial, goods, services, etc.); | |

| 2 = informational support (knowledge or advice); | ||

| 3 = emotional care (affection from others, sharing feelings, etc.); | ||

| 4 = unspecified |

aWe categorised the sources and types of social support in line with previous literature (e.g. Antonucci and Ajrouch 2007; Helgeson 2003). We used ‘providing support’ as a significant determinant to demonstrate older people’s capacity. It denotes older individuals’ physical mobility and mental state, reflecting their autonomy

This research adopted a nonexclusive coding strategy that allowed each news article to be coded into multiple categories and/or subcategories. For example, the experiences of several older men and women during the pandemic were reported in article Paper 069, which was coded into both male and female (under the gender category) and different age groups (under the age category). The remaining articles were coded following the same procedures by the three coders. Each of the 568 news articles was read carefully to ensure that all the relevant text units had been identified and coded according to the coding scheme.

Qualitative content analysis

Following the quantitative content analysis, we then conducted qualitative analysis to investigate the themes that emerged from the classified news excerpts. Instead of measuring the frequency of occurrence of certain terms and core information, the qualitative content analysis focused on language narratives in which actors and acts were described, as well as patterns, cultural references, and social and political practices related to older adults during the pandemic. For example, we analysed how media positioned older adults in the process of receiving and obtaining hygiene training as a type of information resource. This allowed us to understand the media’s perceptions of old age and ageing, which underpinned its portrayal of older people as ignorant and uncooperative in the implementation of COVID-19 prevention measures at the societal level.

The two researchers independently analysed the news excerpts, taking notes and situating the representative cases into a broader social context for interpretation (Rozanova 2010). Weekly meetings were held online to cross-check the themes that we identified from the news content. The qualitative approach enabled us to examine the ways in which media-represented vulnerability of older people helps reinforce ageism (RQ3).

Reliability

Several strategies were employed to improve the reliability of the study. Essential training was offered to research assistants, which helped them understand the purpose, core concepts and coding procedures of this research. The coding scheme was generated and modified along with a series of discussions between coders on the matching of controversial meaning units and categories at different levels. Cross-checks among the coders were conducted before we finished the coding process. We also organised ‘intensive group discussions’ and ‘coder adjudications’ to achieve agreement and assure reliability (Bryman 2008, p. 288; Saldaña 2013, p.57).

Findings

The focal health condition and undifferentiated presentation of older people

We began our analysis with RQ1: What specific groups of older people have been represented as vulnerable in pandemic reporting? Our findings indicated that several groups of older people have attracted more media attention in the pandemic, including COVID-19 patients (31.8%), physically and psychologically frail elders (30.5%), people living in aged-care facilities (25.7%) and people aged 80 and over (25.3%). Despite these differences, the media had a clear preference for constructing older people as a homogeneous group without acknowledging their diverse social, cultural and economic backgrounds.

As shown in Table 2, among the 568 news articles involving older adults, 62.9% did not precisely indicate the age of older people. Instead, media outlets preferred to use vague wording, such as ‘older people’, ‘the elders’ or ‘the retirees’, to refer to older adults.2 Among the articles in which the actual age was given, adults aged 80 and older were explicitly identified (25.3%). Such vagueness and nonspecificity were maintained with regard to gender (69.3% unspecified), source of income (96.1% unspecified), living arrangement (53.6% unspecified), having adult child(ren) or not (76.3% unspecified), and health and digital literacy (95.4%, 93.1% unspecified).

Table 2.

Biomedical and socio-economic status of older people presented in the examined news articles (N = 568)

| Category | Subcategory | Percentage (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomedical | Age | 60–69 | 11.5 |

| 70–79 | 10.1 | ||

| 80 + | 25.3 | ||

| Unspecified | 62.9 | ||

| Gender | Male | 20.1 | |

| Female | 19.4 | ||

| Unspecified | 69.3 | ||

| Health conditions | COVID-19 patient | 31.8 | |

| Non-COVID-19 patients with chronic conditions | 20.7 | ||

| Frail (physically and psychologically) | 30.5 | ||

| Physically and mentally disabled | 19.4 | ||

| Healthy | 3.9 | ||

| Unspecified | 33.7 | ||

| Socio-economic | Source of income | Pension | 1.5 |

| Social benefits (means-tested, age-related, etc.); | 2.8 | ||

| Paid work | 0.5 | ||

| Unspecified | 96.1 | ||

| Living arrangements | Living in aged-care facilities | 25.7 | |

| Living in private dwellings | 17.1 | ||

| Living alone or with spouse only | 15.5 | ||

| Unspecified | 53.6 | ||

| Having adult child(ren) or not | Having adult child(ren) | 21.0 | |

| Childless | 3.5 | ||

| Unspecified | 76.3 | ||

| Health literacy | High | 2.4 | |

| Low | 2.2 | ||

| Unspecified | 95.4 | ||

| Digital literacy | High | 1.5 | |

| Low | 5.6 | ||

| Unspecified | 93.1 |

aThe percentage of each category might add up to over 100%, as we adopted a nonexclusive coding strategy that allowed each news article to be coded into multiple categories

The only exception was the health condition of older adults, which was presented with greater specificity in approximately two-thirds of the news articles (66.3%). While only 3.9% of articles mentioned older people as healthy, the majority of the articles presented older adults through a problematic disease-focused lens, portraying them as infected with the coronavirus (31.8%), frail and susceptible (30.5%), having chronic conditions (20.7%), and physically and mentally disabled (19.4%).

The above findings suggested that the media had adopted an overgeneralised framework to present older people in the COVID-19 pandemic, overwhelmingly emphasising two specific characteristics: old age and poor health. Older people were consequently constructed as physically vulnerable. The socio-economic factors that may have affected the extent of their vulnerability were overlooked.

Older people as support recipients in pandemic-related media representations

Next, we addressed RQ2: How has the media positioned older people in terms of responding to the pandemic? The findings suggested that the ways in which media perceived older people in coping with the challenges to their lives caused by the pandemic were problematic. Among the 568 examined news articles, 53.9% (n = 306) viewed older adults as passive recipients of the resources and support of their families, communities or society at large. In addition, 41.4% (n = 235) of the articles labelled older adults as potential victims whose physical health or lives were put in danger by the spread of coronavirus. Notably, the autonomy and capability of older people to look after themselves and offer help of various types were significantly underrepresented in the news coverage, which only accounted for 10.2% (n = 58) of the collected articles.

As shown in Table 3, formal social protections, referring to the support provided by various levels of government and public institutions and NGOs (such as hospitals), stood out in the news, accounting for 15.0% and 38.6% of the examined 568 news articles, respectively. In comparison, the informal support networks of older people received less coverage from the media, with immediate family members as well as kin, friends and neighbours accounting for 12.1% and 4.05%, respectively.

Table 3.

Media’s portrayal of older people’s response to the pandemic in the examined news articles (N = 568)

| Subcategory | No. of news articles | Percentage (%)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As support recipients (n = 306, 53.9%) | From whom? | Government at all levels | 85 | 15.0 | ||

| Public institutions and NGOs | 219 | 38.6 | ||||

| Immediate family members | 69 | 12.1 | ||||

| Kin, friends, neighbours, etc | 23 | 4.05 | ||||

| What types of support? | Instrumental support (financial, goods, services, etc.) | 284 | 50.0 | |||

| Emotional care (affection from others, sharing feelings, etc.) | 140 | 24.6 | ||||

| Informational support (knowledge or advice) | 98 | 17.3 | ||||

| As support providers (n = 58, 10.2%) | What types of support? | Instrumental support (financial, goods, services, etc.) | 44 | 7.7 | ||

| Emotional care (affection from others, sharing feelings, etc.) | 18 | 3.2 | ||||

| Informational support (knowledge or advice) | 11 | 1.9 | ||||

| As potential victims (n = 235, 41.4%) | ||||||

aThe percentage of each category might add up to over 100%, as we adopted a nonexclusive coding strategy that allowed each news article to be coded into multiple categories. For example, a news article might write about both support recipients and providers among older people

Three types of support, i.e. instrumental, emotional and informational, were all touched upon in the examined news. Among the three types of support, 50.0% of the news articles mentioned instrumental support, such as young-aged volunteers buying food and necessities for older people in quarantine and medical workers providing healthcare services. Emotional care, such as daily phone calls from community centres and video chats with adult children, was mentioned in 24.6% of the news articles. Informational support in the pandemic reporting mainly referred to providing scientific knowledge about COVID-19 and hygiene education to older people, which accounted for 17.3% of the examined news articles.

While older people were predominantly presented as recipients of support in the pandemic reporting, their contributions to controlling the COVID-19 pandemic were significantly underrepresented. An online survey conducted in May by the Chinese National Institution of Women Studies (2020) found that people aged 60 and over were very active in participating in volunteering work during the pandemic, with a higher level of participation among women. Despite the empirical evidence, our study found that older people’s contributions had not been given sufficient representation in the media coverage. A small number of the examined articles (10.2%, n = 58) acknowledged older people as support providers, emphasising three types of practices: retirees doing volunteering work in the community, poor elders making financial donations and retired medical workers returning to work.

The underlying ageism in pandemic-related media representations of older people

Based on the quantitative findings, we further conducted qualitative content analysis on the excerpts to answer RQ3: How did the media representation of vulnerability in old age help reinforce ageism? Three themes emerged from our data analysis.

First, the media has shown a strong preference for formulating a dichotomised relational structure in the news, contrasting the young and the old in various aspects, including their physical and cognitive functions, psychological status, learning ability and lifestyles. As shown in one article:

Different from normal adults, older people’s body functions have various problems. Their psychological status has also changed, i.e. feeling more anxious and depressed when facing disease. Researchers should target older people and provide them with suggestions matching their specific needs. (Paper 024, 2-6)

Apparently, being old was opposite from being ‘normal’, as it was equated with all kinds of negative qualities, such as becoming vulnerable, frail and depressed.

In addition to physical frailty, older people were also frequently portrayed as stubborn and ignorant. For example, older adults were perceived as target audiences who ‘needed extra hygiene education and supervision from the younger generation because their cognitive functions have deteriorated’, ‘they tended to have a blind optimism’ and ‘made judgements based on their outdated experience’ (Caixin 057, 2–18; Paper 006, 1–24; Paper 040, 2–11). As one ironically put it, ‘if we want older people to fully understand the pandemic, information must be communicated in their way’. (Southern weekly 001, 1–25).

Second, pandemic reporting portrayed older people as a ‘symbolic threat’ (Stephan and Stephan 2017) to public health by emphasising their biomedical susceptibility to the virus and the necessity of strengthening the quarantine management of the older population. As one wrote:

Pandemic control is facing many challenges in this city district because the proportion of old-aged residents is high. This population is vulnerable and susceptible. In addition, they are not properly aware of the pandemic prevention and face more challenges in utilising digital technology.… Therefore, community staff should pay more attention to neighbourhoods like this (with a large proportion of older people), urging these people to strictly follow the stay-at-home rules. (Caixin 035, 2-10)

In the above excerpt, older people were generally believed to be biomedically susceptible to the virus and therefore needed extra protection and quarantine management. As Cook and Powell (2007) have pointed out, the longstanding old-age-related social policy discourse in China was subjected to the impacts of the biomedical model, which constructed old age as a process of physical decline. As a result, the physical vulnerability of older adults was central to government management, which was amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The ‘symbolic threat’ was fully represented in the debate on ‘how to persuade older parents to wear masks’. As the Southern weekly (001, 1–25) wrote:

The proportion of older people in the entire population is very high in China now. The younger generation has learned the severity of the pandemic from the internet, however for the stubborn old people who do not trust online sources, how can we make them understand the severity of the situation? Their lack of understanding of the situation will be a great potential risk to all of us.

The media reported that older people increased intergenerational tensions and reinforced ageist attitudes towards older populations, thus increasing the risks of generating age discrimination against older individuals in their daily lives.

Third, the fact that older people were largely portrayed as recipients of support during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed the media’s limited understanding of the elders’ competencies and capabilities to proactively respond to the pandemic. Delving into the rare cases that presented older adults as support providers enabled a better understanding of how the media recognises and assesses older people’s contributions to society.

Biased perceptions towards older people’s competencies can be found in news reports praising poor older people who make financial donations (Ayalon 2020). For instance, a news article quoted a donor’s words to illustrate their motivation for making donations:

I [the 69-year-old donor] have been counting on the government’s social benefits for years. Now our country is facing difficulty because of the pandemic. I must make some donation. Otherwise, I would feel guilty…. I have seen young people doing many things to fight against the pandemic. I’m too old to follow suit, donating money is the only contribution that I can make. (Xinhua 068, 2-10)

As shown in the excerpts, older people donating money were portrayed as showing gratitude to the previous long-term support received from the government and as the only way to prove their self-worth.

Globally, older people are seen as financially dependent, although they have worked to make lifelong contributions to the development of countries. This viewpoint has been commonly found in the media discourse, creating intergenerational conflicts (Wilińska and Cedersund 2010). Similarly, older people in China, especially recipients of old-age benefits, have internalised this viewpoint and therefore feel guilty about relying on the government. While being portrayed as demanding relatively more medical resources in the pandemic, older people’s sense of guilt for being dependent was amplified by the media.

The media’s praise of people who made donations and its resulting encouraging effect not only generated moral pressure on those who had no intention of making a donation but also failed to recognise the non-financial forms of the contributions made by many older people in the COVID-19 pandemic (Petretto and Pili 2020). The media’s biased perception of older people’s contribution presented a poor comprehension of older adults’ value.

Discussion

This paper set out to investigate the media’s representation of the vulnerability of older people and its implications for understanding ageism in the COVID-19 pandemic. Guided by the analytical framework, we combined both quantitative and qualitative content analyses to examine which specific groups of older people were represented as vulnerable, how they were positioned in the process of obtaining resources to live through the pandemic, and how the media construction of vulnerability in old age helps to reinforce ageism.

Our findings suggested that biomedical factors (i.e. age and health conditions) outweighed socio-economic factors in determining how media represented older adults in the pandemic. The biomedical-focused view of vulnerability revealed that old age was automatically translated into vulnerability and dependency, as well as making a limited contribution (Phelan 2018; Wilińska and Cedersund 2010). In fact, the vulnerability of older people was largely affected by their disadvantaged socio-economic status and emergency management policies which discriminated against older people (Grundy 2006; Monahan et al. 2020; Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti 2006). The ignorance of socio-economic factors uncovered that the media has adopted a biased lens to present older people’s vulnerability.

In this study, we have seen a large proportion of news articles writing mainly about older people who relied on health and social services provided by hospitals and aged-care facilities. The way the media chose to represent older adults’ who availed themselves of health and medical resources portrayed them as being dependent on care. In doing so, the media ignored the in-group diversity among older people and further misrepresented them as inactive and unproductive individuals (Ainsworth and Hardy 2007; Lowsky et al. 2014). As Ayalon et al. (2020) noted, although protecting those who were most vulnerable to the virus was commendable, it was also ageist to compromise older adults’ autonomy and disregard their social contribution.

The unidimensional media representation of older adults could cause problems at the receiving end (Kroon et al. 2019). The ‘old age as a threat’ signal sent through the media evoked feelings of false safety across society (Lundgren and Ljuslinder 2011). This increased other age groups’ concerns about the risks that older adults as a separate group posed to public health, impeding a unified response towards the COVID-19 pandemic at the societal level (Ehni and Wahl 2020).

Modern gerontological studies have emphasised the diversity of the older population and the ageing process (Grundy 2006; Nelson and Dannefer 1992). The experiences of ageing are multidimensional and engaged with the social, physical and cultural environments where they emerged (Heikkinnen 2000). Hence, there is no simple causal link between the vulnerability of people to the pandemic and their chronological age. Other shaping factors, including gender, wealth and family structure, must be taken into account in the determination of who was vulnerable to the COVID-19 (Pritchard-Jones 2016). An adequate understanding of vulnerability helps aged-care practitioners better meet older people’s needs, thus improving their work with and services for older people. It propels policymakers to recognise the correlation between vulnerability and social service provision for the increasingly ageing population, enacting ageing-related social policies to enhance the quality of life and well-being of older people.

Media content has an impact on people regarding self-identification and their approach towards other persons (Iversen and Wilińska 2020; Lin et al. 2004). Ageist attitudes communicated and amplified by media help create a disadvantaged situation in which older people are more likely to experience age discrimination, which has a negative impact on their mental health (Ayalon et al. 2020; Monahan et al. 2020). The media must take its social responsibility to avoid stereotyping the elders and to inform older individuals of ageism and its harm to their age group, which is crucial to preventing older people from internalising ageist thinking. The findings of this study may also be used to raise awareness among policymakers, care service providers and family members of the importance of eliminating ageist attitudes so that the value of older individuals can be fully recognised.

Limitation and implications for future studies

The findings of this research were based on data collected from five Chinese media outlets to study the media representation of older people’s vulnerability to COVID-19 in China. Our findings may not be generalisable to analysing the news reports on older people in other countries. As a global public health crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic allows us to move beyond the Chinese case to examine shared problematic media coverage on older people across countries.

The media content examined in this research was produced amid the first wave of COVID-19 in China. With the coronavirus continuously affecting people’s lives all over the world, it is of great importance to carry out cross-country comparative studies or longitudinal research. In addition to the textual content produced by media, other forms of media text created by print media or digital media are equally important to improving our understanding of media representations of vulnerability in old age as well as ageism. In the post-pandemic era, conducting face-to-face interviews with older individuals will significantly enrich our knowledge of their experiences of being vulnerable and their perceptions of ageism in a public health crisis.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the “Zhishan Young Scholar Support Programme” of Southeast University and Moral Development Institute. We thank Prof. Dr. Clemens Tesch-Roemer and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions.

Footnotes

The phoneticised Chinese keywords are presented here together with their English translation, helping readers to better capture the original meaning of the terms.

In the context of China, older people commonly referred to a wide age range of adults aged 60 and over.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ainsworth S, Hardy C. The construction of the older worker: privilege, paradox and policy. Discourse Commun. 2007;1(3):267–285. doi: 10.1177/1750481307079205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ. Social resources. In: Mollenkopf H, Walker A, editors. Quality of life in old age: international and multi-disciplinary perspectives. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007. pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L. There is nothing new under the sun: ageism and intergenerational tension in the age of the COVID-19 outbreak. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(10):1221–1224. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220000575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L, Tesch-Römer C. Taking a closer look at ageism: self- and other-directed ageist attitudes and discrimination. Eur J Ageing. 2017;14:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s10433-016-0409-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L, et al. Aging in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: avoiding ageism and fostering intergenerational solidarity. J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 2020;1–4:e49. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MW. Classical content analysis: a review. In: Bauer MW, Gaskell G, editors. Qualitative researching with text, image and sound. London: Sage; 2000. pp. 131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Brocklehurst H, Laurenson M. A concept analysis examining the vulnerability of older people. Br J Nurs. 2008;17(21):1354–1357. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.21.31738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryman A. Social research methods. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Larrañaga,, et al. COVID-19: risk accumulation among biologically and socially vulnerable older populations. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;63:101149. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH. Advertising representations of older people in the United Kingdom and Taiwan: a comparative analysis. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2015;80(2):140–183. doi: 10.1177/0091415015590305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung JC, Kwan AY. The utility of enhancing filial piety for elder care in China. In: Chen S, Powell JL, editors. Aging in China: implications to social policy of a changing economic state. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese National Institution of Women Studies (2020) Survey report on “SHE power” in fighting against COVID-19. https://page.om.qq.com/page/OzHtBviiIqMrLr4FXfv2qH2Q0. Accessed 22 September 2020

- Cook IG, Powell JL. Ageing urban society: discourse and policy. In: Wu F, editor. China’s emerging cities: the making of new urbanism. New York: Routledge; 2007. pp. 126–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ehni HJ, Wahl HW. Six propositions against ageism in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32(4–5):515–525. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1770032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fealy G, McNamara M, Treacy MP, Lyons I. Constructing ageing and age identities: a case study of newspaper discourses. Ageing Soc. 2012;32(1):85–102. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X11000092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S, et al. (2020) Ageism and COVID-19: what does our society’s response say about us? Age and ageing 49(5): 692–695. https://doi:10.1093/ageing/afaa097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Grundy E. Ageing and vulnerable elderly people: European perspectives. Ageing Soc. 2006;26:105–134. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X05004484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinnen R. Ageing in an autobiographical context. Ageing Soc. 2000;20(4):467–483. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X99007795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS. Social support and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(Suppl. 1):25–31. doi: 10.1023/A:1023509117524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen S, Wilińska M. Ageing, old age and media: critical appraisal of knowledge practices in academic research. Int J Ageing Later Life. 2020;14(1):129–149. doi: 10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.18441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones H, Powell J. Old age, vulnerability and sexual violence: implications for knowledge and practice. Int Nurs Rev. 2006;53(3):211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2006.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SJ, Jung SI. Age-related morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID-19. Inf Chemother. 2020;52(2):154–164. doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler E, Bowen CE. COVID ageism as a public mental health concern. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2020;1.1:e12. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen S, Salminen L, Leino-Kilpi H. Media portrayal of older people as illustrated in Finnish newspapers. Int J Qual Stud Health Wellbeing. 2014;9(1):25304. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v9.25304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon AC, et al. Biased media? How news content influences age discrimination claims. Eur J Ageing. 2019;16:109–119. doi: 10.1007/s10433-018-0465-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MC, Hummert ML, Harwood J. Representation of age identities in on-line discourse. J Aging Stud. 2004;18:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2004.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowsky DJ, Olshansky SJ, Bhattacharya J, Goldman DP. Heterogeneity in healthy aging. J Gerontol Ser A Biomed Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:640–649. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren AS, Ljuslinder K. The baby-boom is over and the ageing shock awaits: populist media imagery in news-press representations of population ageing. Int J Ageing Later Life. 2011;6(2):39–71. doi: 10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.116233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Williams C, O’Neill D. Retrospective analysis of attitudes to ageing in the Economist: apocalyptic demography for opinion formers. BMJ. 2009;339:b4914. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner M, Duncan MC, Jensen K. Separating the men from the girls: the gendered language of televised sports’. Gend Soc. 1993;7:121–137. doi: 10.1177/089124393007001007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan C, Macdonald J, Lytle A, Apriceno M, Levy SR. COVID-19 and ageism: how positive and negative responses impact older adults and society. Am Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1037/amp0000699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EA, Dannefer D. Aged heterogeneity: fact or fiction? The fate of diversity in gerontological research. Gerontol. 1992;32(1):17–23. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petretto DR, Pili R. Ageing and COVID-19: what is the role for elderly people? Geriatrics. 2020;5(2):25. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics5020025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan A. Researching ageism through discourse. In: Ayalon L, Tesch-Römer C, editors. Contemporary perspectives on ageism. Berlin: Springer; 2018. pp. 547–562. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard-Jones L. The good, the bad, and the ‘vulnerable older adult’. J Soc Welf Family Law. 2016 doi: 10.1080/09649069.2016.1145838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds L. The COVID-19 pandemic exposes limited understanding of ageism. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32(4–5):499–505. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1772003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanova J. Discourse of successful aging in The Globe & Mail: insights from critical gerontology. J Aging Stud. 2010;24:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2010.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: SAGE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvimäki A, Stenbock-Hult B. The meaning of vulnerability to older persons. Nurs Ethics. 2014;23:372. doi: 10.1177/0969733014564908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti A framework for understanding old-age vulnerabilities. Ageing Soc. 2006;26:9–35. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X05004423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sominsky L, Walker DW, Spencer SJ. One size does not fit all: patterns of vulnerability and resilience in the COVID-19 pandemic and why heterogeneity of disease matters. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan WG and Stephan CW (2017) Intergroup threat theory. In: Kim YY (ed) The international encyclopedia of intercultural communication. doi 10.1002/9781118783665.ieicc0162, pp 1–12

- Wilińska M, Cedersund E. “Classic ageism” or “brutal economy”? Old age and older people in the Polish media. J Aging Stud. 2010;24(4):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2010.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YB, Harwood J. Modernization of tradition in an age of globalization: cultural values in Chinese television commercials. J Commun. 2004;54:156–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02619.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]