Abstract

Summary: A ruptured dissecting right vertebral artery aneurysm was treated by means of double stent placement with two overlapping stents. Control angiography performed 3 d after stent placement revealed beginning aneurysmal thrombosis. Substantial reduction in aneurysmal size was observed after 4 wk, whereas total occlusion was observed after 3 mo. The reduced stent porosity caused by the overlapping stents, which result in significant hemodynamic changes inside the aneurysmal sac, may accelerate intraaneurysmal thrombosis and may be helpful in achieving a more rapid complete occlusion compared with that achieved by single stent placement.

Case Report

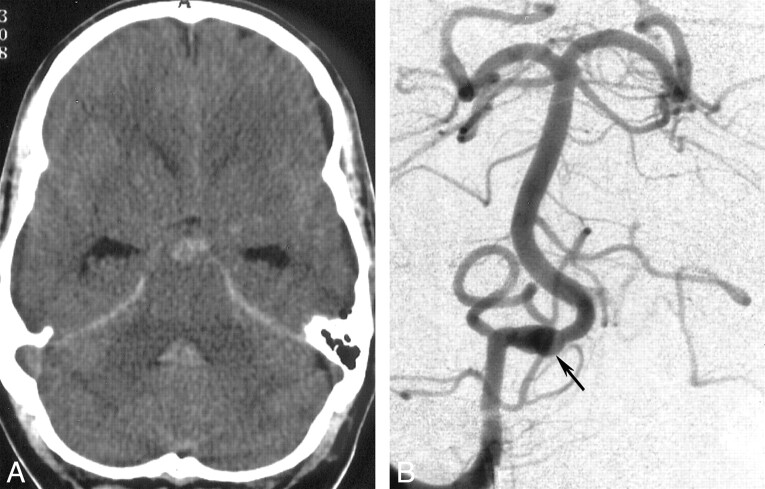

A 47-year-old man presented at another institution with a Hunt and Hess grade IV subarachnoid hemorrhage. His CT scan revealed subarachnoid hemorrhage that was more marked in the prepontine cistern and initial mild hydrocephalus (Fig 1A). Digital subtraction angiography revealed a fusiform aneurysm involving the terminal intracranial segment of the right vertebral artery, distal to the origin of the right posterior inferior cerebellar artery (Fig 1B). The hydrocephalus progressed and was treated with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt within the first days. Because of the patient's critical condition, the neurosurgeons postponed treatment. Four weeks later, the patient recovered remarkably and was referred to our institution. At admission, he had headache but no motor or sensory deficits.

fig 1.

Initial images.

A, Transverse CT scan obtained on the day of admission. Blood is present within the prepontine subarachnoid space and fourth ventricle.

B, Anteroposterior arteriogram obtained with a right vertebral artery injection. Fusiform dilatation of the distal vertebral artery, distal to the posterior inferior cerebellar artery origin, indicates intracranial dissection (arrow).

Because follow-up arteriograms showed that the aneurysm had grown significantly (Fig 2), endovascular management was considered the therapy of choice. First, the patient underwent a balloon test occlusion of the distal right vertebral artery (proximal to posterior inferior cerebellar artery origin) that lasted 25 min; this procedure was well tolerated. Because of the favorable anatomic conditions in the dissected vessel segment, stent placement was considered the endovascular method of choice. The aneurysmal dome measured 6 × 8 mm with a 5-mm neck, and the vertebral artery measured 3 mm in the distal segment and 3.4 mm in the proximal segment.

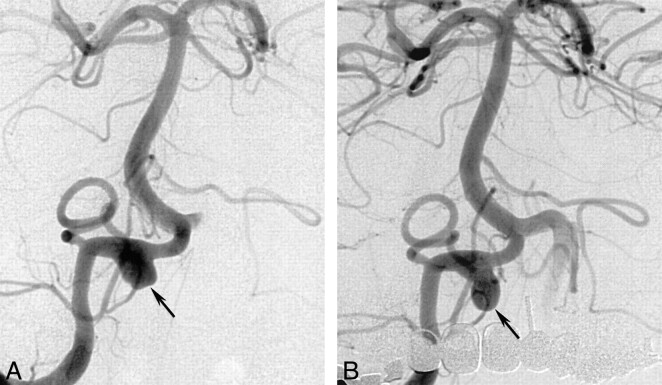

fig 2.

Follow-up anteroposterior arteriograms obtained with a right vertebral artery injection 5 wk after bleeding.

A, Image shows aneurysmal growth (arrow) of approximately 8 mm.

B, Image shows a further slight increase (arrow) in the size of the dome, 5 d later.

According to the protocol for intracranial stent placement in our hospital, the patient received clopidogrel (75 mg twice daily) and aspirin (325 mg twice daily) by means of oral administration beginning 4 d before the procedure. After undergoing stent placement, the patient received clopidogrel (75 mg twice daily) for 6 wk and aspirin (325 mg daily) indefinitely.

The procedure was performed with the patient under general anesthesia. At the start of the procedure, the patient received a heparin bolus (5000 IU), which was flushed with saline and heparin (1 U heparin per milliliter of isotonic sodium chloride solution at a rate of 100 mL/h) with use of a rotating hemostatic valve.

A 6F guiding catheter (Cordis Envoy; Cordis Endovascular) was positioned as high as possible in the right vertebral artery; an additional 4F groin sheath was inserted into the left common femoral artery. The dissected vertebral artery segment was crossed with a 0.014-in guidewire (Transend; Boston SC) that was advanced into the contralateral vertebral artery as distally as possible to provide enough support. Then, a 3 × 12- mm stent (AVE S670; Medtronic) was initially deployed, covering the vessel segment distal to the neck and covering the neck itself. Additionally, an overlapping 3 × 18-mm stent (AVE S670; Medtronic) was carefully positioned to traverse the first one. After it was confirmed at control arteriography to partially overlap the first stent, the aneurysmal neck, and the vessel segment proximal to the neck, the second stent was deployed. Before withdrawing, the balloon was carefully rotated and slightly pushed under a blank road map to avoid any migration of the stents during removal of the catheter. The 0.014-in guidewire was left in place throughout the procedure.

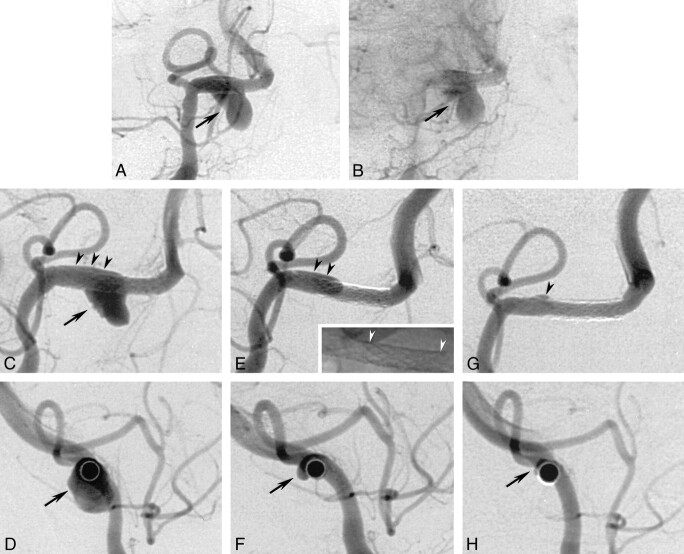

Control angiography performed at the end of the procedure revealed a patent vertebral artery and good coverage of the aneurysmal neck by the two overlapping stents (Fig 3A). The size of the aneurysm was unchanged, but the late-phase images revealed some stagnation of contrast material (Fig 3B). Neither technical complications nor neurologic sequelae were observed. The patient completely recovered within the first week, without retaining any residual neurologic deficits. Arteriography was performed 3 d after stent placement to identify possible early changes of the aneurysmal filling; it revealed a slight decrease in aneurysmal size due to the beginning of intraaneurysmal thrombosis (Fig 3C and D). Arteriograms obtained 4 wk after stent placement confirmed patent stents and showed substantial regression of the aneurysmal dome (Fig 3E and F). The 3-mo follow-up examination revealed total occlusion of the aneurysm (Fig 3G and H).

fig 3.

Arteriograms obtained after stent placement.

A and B, Anteroposterior projection arteriograms obtained immediately after stent placement. After deployment of two overlapping stents (S670, 3/12 and 3/18 mm) distal to the posterior inferior cerebellar artery origin, the aneurysmal neck is fully covered by the portion with reduced porosity. The vertebral artery is patent, and the aneurysm still shows filling; however, a minimal delay in the washout of the intraaneurysmal filling is observed (arrow).

C, Right anteroposterior-oblique arteriogram obtained 3 d after stent placement. The overlapping stents are patent, but the aneurysmal dome shows some small filling defects adjacent to the aneurysmal wall (arrow) consistent with the beginning of intraaneurysmal thrombosis. A small amount of contrast medium is seen in the space between the stents and the proximal vessel wall where the stents are not completely adjacent to the vessel wall (arrowheads).

D, Lateral orthogonal projection of the course of the artery, obtained 3 d after stent placement, more clearly shows the circumferential extent of the pseudoaneurysm (arrow) during the post–stent-placement stage

E, Right anteroposterior-oblique arteriogram obtained 4 wk later. The two stents are patent, whereas the aneurysm shows subtotal occlusion. The filling of the extra space is now diminished in its extension (black arrowheads) and corresponds to the decreased size of the pseudoaneurysm in F. This probably does not represent the original arterial wall but rather the dissecting membrane that is the initial part of the developed pseudoaneurysm. Miniature: nonsubstracted image of the two stents shows the overlapping portion between the white arrowheads.

F, Lateral orthogonal projection of the course of the stented artery, obtained 4 wk after stent placement, more clearly shows the circumferential extent of the pseudoaneurysm (arrow) during the regression stage.

G, Right anteroposterior-oblique arteriogram obtained 3 mo after stent placement shows complete occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm, with minimal extravasation in the area of the previously dissected arterial wall (arrowhead). A patent right vertebral artery with no notable intimal hyperplasia is depicted.

H, Lateral orthogonal projection of the course of the stented artery, obtained 3 mo after stent placement, more clearly shows the total occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm (arrow).

Discussion

Findings of experimental studies (1, 2) have shown that a metallic stent, bridging the aneurysmal neck, may alter the flow pattern within the aneurysm, promoting thrombus formation and aneurysmal occlusion. Although immediate aneurysmal occlusion can be seen after single stent placement for treatment of extracranial pseudoaneurysms (3, 4), in some cases, 3–6 mo (5–8) or longer (6, 7, 9) may pass before occlusion occurs. To achieve faster complete aneurysmal occlusion, the combination of stents and detachable coils has been suggested for extracranial, as well as intracranial, aneurysms (10–13), and the combination is currently considered an alternative to single stent placement or other techniques such as the remodeling technique or parent vessel occlusion. Lylyk et al (11) and Sekhon et al (13) described successful treatment of ruptured vertebral artery aneurysms with the use of a stent as a buttress against coil migration. Lanzino et al (10) reported 10 cases managed with stent-supported coil embolization; they achieved aneurysmal occlusion of more than 90% in eight patients. In four of these patients, treated with stent placement only, no evidence of intraaneurysmal thrombosis was found either immediately or during follow-up studies performed 48 h (two patients), 4 d (one patient), and 3 mo (one patient) after treatment. Phatouros et al (12) recently reported a series of seven patients with fusiform aneurysms, wide-neck aneurysms, or pseudoaneurysms who underwent stent-supported coil embolization; technical success was achieved in six. In one patient, a coil became entangled with the stent, resulting in partial coil delivery into the parent artery with no neurologic sequelae.

Certain limitations, however, may be encountered when stents are used in conjunction with coils (12). Regarding stent size, in some cases, a microcatheter (even one as small as 0.014 or 0.010 in diameter) can be navigated through the stent interstices only with great difficulty. Regarding visualization of coils, packing can be inaccurate because of the density of platinum detachable coils. Multiple projections may become necessary, particularly with fusiform aneurysms, and in some cases, complete packing of the aneurysm cannot be achieved. Regarding entanglement, coil loops may become entangled with the stent struts and unravel during attempts to retrieve them, leading to the risk of moving the stent or leaving coils within the parent artery. In our opinion, retrieval of coils might be more complicated because the microcatheter is embedded between the stent struts. In comparison with conventional coiling, this method involves friction between the coil and the catheter that cannot be reduced by changing the position of the catheter, as is usually advisable.

Theoretically, stent-grafts are the ideal implants for covering arterial aneurysms, but, at present, they are still in technical development. They have several disadvantages, such as increased thrombogenicity (12) and inflammatory reaction with subsequent intimal hyperplasia. Of particular importance in the intracranial circulation is that they are less flexible than are bare stents.

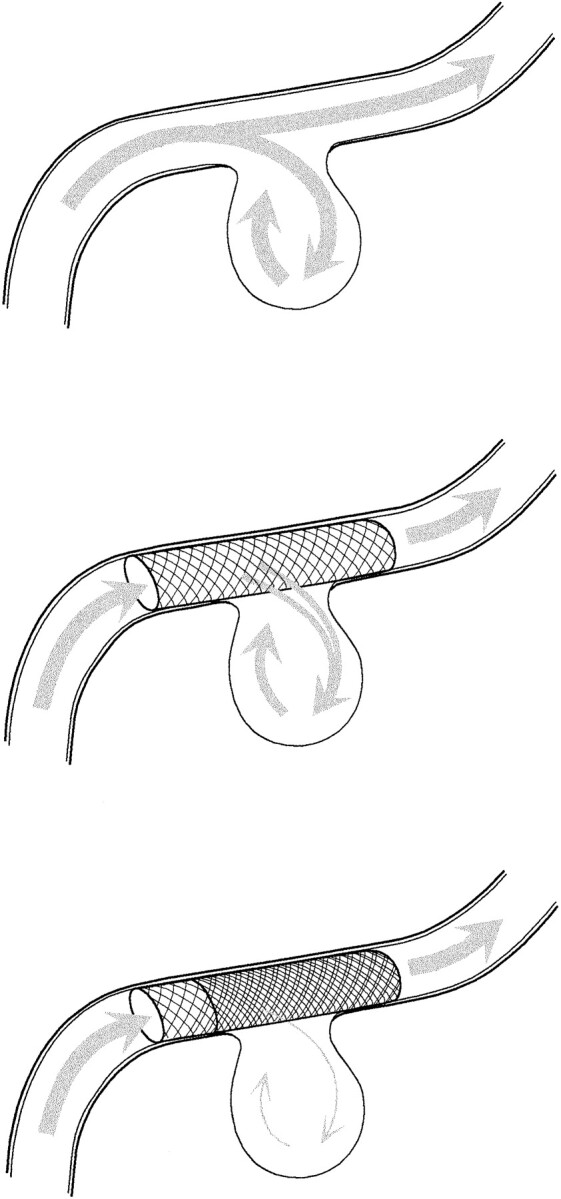

To our knowledge, the use of double stent placement for complete exclusion of wide-neck aneurysms has been reported in only a single case to date (14), but double stent placement may be a relatively simple technique to more effectively change intraaneurysmal flow and achieve subsequent thrombosis. The influence of stent porosity on changing the local hemodynamics between the aneurysm and the parent vessel was shown in the experimental studies by Lieber et al (15) and Wakhloo et al (16). In a recent experimental study, Yu and Zhao (17) showed that the damping of the intraaneurysmal flow with stents is effective if the ratio of the effective mesh area and the total surface of the stent are sufficiently small, regardless of the size of the aneurysm. The flow movement inside the aneurysmal pouch can be suppressed to less than 5% of the bulk mean flow velocity, inducing intraaneurysmal thrombus formation.

On the basis of our preliminary experience in extracranial aneurysms, we decided to cover the aneurysmal neck by using two overlapping coronary stents. Although only a minor change in the filling of the aneurysm was visible at the end of the procedure, 3-d follow-up clearly revealed beginning thrombosis, which continued and resulted in a substantial reduction of the aneurysmal size, that was observed after 4 wk. Because some aneurysms may show decreasing and then increasing lumen size as the thrombus forms and then resolves, we performed a second follow-up examination 8 wk later. This 3-mo control arteriographic examination revealed total occlusion of the aneurysm, with only a minimal extravasation as a remnant of the initial dissecting process. The result accomplished in our case supports the experimental results discussed previously and shows that reducing stent porosity may considerably impede the intraaneurysmal blood flow and accelerate the intrasaccular thrombus formation. Although the long-term validity of this result still remains uncertain, we think that the patient's risk of subsequent bleeding is markedly reduced.

Placement of overlapping stents increases the amount of foreign body material within the arterial wall and thus increases the risk of inflammatory vessel wall reaction, resulting in luminal stenosis due to neointimal hyperplasia. On the other hand, the placement of overlapping stents and use of double stents are common practice in cardiology and seem to be safe (18).

Furthermore, in our own experience, a 20-mo follow-up arteriogram obtained after double stent placement in an extracranial carotid aneurysm showed only a mild nonstenotic intimal hyperplasia. This occurred, however, in the area of the stent margins covered by the proximal single wall stent but not in the area of stent overlap (19).

Adequate stents with low porosity are not available at the moment, and, in particular, the intracranial stents that are currently used are highly porous. Thus, the double stent placement technique may be indicated more often in the intracranial than in the extracranial territory. On the other hand, the smaller intracranial arteries are more sensitive to stent implantation (2), and intimal proliferation is more likely to occur in these arteries than in the extracranial vessels (20). We emphasize, as did Lanzino et al (10), the need for early and careful angiographic follow-up in all patients undergoing intracranial stent implantation.

In the case presented herein, trapping of the aneurysm by performing parent vessel occlusion between the posterior inferior cerebellar artery and the vertebrobasilar junction would have been another option. Our concern, however, was the risk of rupturing the dissected arterial segment (starting immediately distal to the posterior inferior cerebellar artery origin) by performing either permanent balloon occlusion in this location or balloon test occlusion, which is necessary if coils are used.

We propose double stent placement as a new, feasible technique for the occlusion of intracranial wide-neck aneurysms, especially pseudoaneurysms. It may represent an alternative, less time-consuming, and less complicated option to stent-supported coil treatment. Additional experience, long-term follow-up, and comparison with other neurointerventional techniques are needed to determine the value of this technique.

fig 4.

Illustration of the reduction of the intra-aneurysmal flow caused by decreased porosity due to double stent placement

Acknowledgments

We thank Corinna Naujock for preparation of the illustration.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Goetz Benndorf, MD, Neuroangiography/Neurointervention, Department of Radiology Charité, Campus Virchow, Humboldt-University Berlin, Augustenburger Platz 1, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

References

- 1.Geremia G, Haklin M, Brennecke L. Embolization of experimentally created aneurysms with intravascular stent devices. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994;15:1223-1231 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wakhloo AK, Schellhammer F, de Vries J, Haberstroh J, Schumacher M. Self-expanding and balloon-expandable stents in the treatment of carotid aneurysms: an experimental study in a canine model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994;15:493-502 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horowitz MB, Miller G III, Meyer Y, Carstens G III, Purdy PD. Use of intravascular stents in the treatment of internal carotid and extracranial vertebral artery pseudoaneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996;17:693-696 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu AY, Paulsen RD, Marcellus ML, Steinberg GK, Marks MP. Long-term outcomes after carotid stent placement treatment of carotid artery dissection. Neurosurgery 1999;45:1368-1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein SM, Coldwell DM, Prall JA, Brega KE. Treatment of traumatic carotid pseudoaneurysm with endovascular stent placement. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1997;8:1065-1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duke BJ, Ryu RK, Coldwell DM, Brega KE. Treatment of blunt injury to the carotid artery by using endovascular stents: an early experience. J Neurosurg 1997;87:825-829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurst RW, Haskal ZJ, Zager E, Bagley LJ, Flamm ES. Endovascular stent treatment of cervical internal carotid artery aneurysms with parent vessel preservation. Surg Neurol 1998;50:313-317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuura JH, Rosenthal D, Jerius H, Clark MD, Owens DS. Traumatic carotid artery dissection and pseudoaneurysm treated with endovascular coils and stent. J Endovasc Surg 1997;4:339-343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez-Cruet MJ, Patwardhan RV, Mawad ME, Rose JE. Treatment of dissecting pseudoaneurysm of the cervical internal carotid artery using a wall stent and detachable coils: case report. Neurosurgery 1997;40:622-626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanzino G, Wakhloo AK, Fessler RD, Hartney ML, Guterman LR, Hopkins LN. Efficacy and current limitations of intravascular stents for intracranial internal carotid, vertebral, and basilar artery aneurysms. J Neurosurg 1999;91:538-546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lylyk P, Ceratto R, Hurvitz D, Basso A. Treatment of a vertebral dissecting aneurysm with stents and coils: technical case report. Neurosurgery 1998;43:385-388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phatouros CC, Sasaki TY, Higashida RT, et al. Stent-supported coil embolization: the treatment of fusiform and wide-neck aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. Neurosurgery 2000;47:107-115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sekhon LH, Morgan MK, Sorby W, Grinnell V. Combined endovascular stent implantation and endosaccular coil placement for the treatment of a wide-necked vertebral artery aneurysm: technical case report. Neurosurgery 1998;43:380-384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benndorf G, Lehmann T, Schneider G, Wellnhofer E. Double stenting: technique to accelerate occlusion of a dissecting carotid artery aneurysm. Neuroradiology 1999;41: (suppl) 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lieber BB, Stancampiano AP, Wakhloo AK. Alteration of hemodynamics in aneurysm models by stenting: influence of stent porosity. Ann Biomed Eng 1997;25:460-469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakhloo AK, Lanzino G, Lieber BB, Hopkins LN. Stents for intracranial aneurysms: the beginning of a new endovascular era? Neurosurgery 1998;43:377-379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu SC, Zhao JB. A steady flow analysis on the stented and non-stented sidewall aneurysm models. Med Eng Phys 1999;21:133-141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Escaned J, Hernandez R, Baquero M, et al. Double stenting as a treatment for stent collapse in the left main coronary artery. J Invasive Cardiol 1999;11:305-308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benndorf G, Campi A, Schneider GH, Wellnhofer E, Unterberg A. Overlapping stents for treatment of a dissecting carotid artery aneurysm. J Endovascular Therapy (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Reiter BP, Marin ML, Teodorescu VJ, Mitty HA. Endoluminal repair of an internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1998;9:245-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]