Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Incomplete stent apposition after carotid angioplasty and stent placement (CAS) is often seen but little is known about how the incomplete attachment goes after stent placement. For example, some may change into restenosis around the stent edge and some may remain unchanged. The purpose of this study is to clarify the morphologic prognosis of an incomplete stent apposition at the stent edge.

METHODS: CAS was attempted on 135 consecutive stenotic lesions (124 patients). Angiograms were then evaluated immediately after the procedure. An incomplete stent apposition at stent edge was found in 15 patients, and all of them were followed up by angiography and MR imaging with antiplatelet therapy.

RESULTS: No ischemic event caused by the lesions occurred during the mean follow-up period of 11 months (from 4 to 32 months). The angiography findings of 15 lesions at a mean of 8.8 months (from 2 to 28 months) after CAS showed that all remained unchanged. No patients required any additional intervention. No new ischemic lesions were detected in any of the 15 patients who underwent follow-up MR imaging at a mean of 10 months (from 2 to 32 months) after CAS.

CONCLUSION: In this study, the existence of a segment of incomplete stent apposition had no adverse morphologic or clinical effect.

Carotid angioplasty and stent placement (CAS) has been shown to be an effective treatment for patients with carotid artery stenosis.1,2 However, the occurrence of an incomplete attachment between the stent and vessel wall after CAS has not been well discussed or documented to date. An incomplete apposition between the stent filaments and the arterial wall can increase the risk of an embolic source as a result of the stagnation of the blood flow in the dead space.3 A strong compression of the vessel wall on the opposite side of the unattachment at the stent edge because of the straightening effect on tortuous vascular curves may induce a kink in the artery that thus could possibly cause edge restenosis. In our previous study, we showed that a residual carotid plaque ulceration directly around a stent improved spontaneously.4 The purpose of our study was to assess the morphologic and clinical changes of an incomplete attachment at the stent edge after CAS.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 135 CAS procedures performed in 124 patients with carotid stenosis at our institute between February 2001 and December 2004. These 135 procedures represented all CAS done at our institution during the interval of this study. All patients received aspirin (81 mg/day) and ticlopidine (200 mg/day) for at least 3 days before CAS. Under general anesthesia, CAS was performed with a cerebral protection device (Naviballoon, Silascon, Kaneka Medix, Tokyo, Japan; PeucuSurge, Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn), after a bolus injection of heparin (80 IU/kg).5 A self-expandable stent, either the Wallstent (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass) or SMART stent (Cordis, Miami Lakes, Fla) was applied after adequate predilation using an angioplasty balloon.5 The Wallstent was used for 107 cases and the SMART stent was used for 28 cases. Atropine sulfate (0.5 mg) was given intravenously just before balloon inflation. The selected stent was 1 to 1.2 times the diameter of the proximal reference vessel. Postdilation was performed only to dilate any residual stenosis of more than 20%. The lesions were evaluated with angiography in anteroposterior and lateral directions immediately after CAS. An incomplete stent apposition at the stent edge was defined in this report as an open space around a stent in the vessel. An incomplete stent apposition at the stent edge was detected in 15 patients (13 men and 2 women) by angiography immediately after CAS. As a result, 15 patients were followed up with antiplatelet therapy (81 mg/day of aspirin and 200 mg/day of ticlopidine). Follow-up neurologic examinations were performed at our clinic. Angiography and MR imaging were scheduled during the follow-up period. All images were evaluated by 2 neurosurgeons (M.O. and K.K.). The degree of stenosis was presented as mean ± SD. The difference between 2 groups was examined by means of χ2 test. A value of P < .05 was chosen to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The clinical characteristics and follow-up findings in these 15 patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the 15 patients was 72 years, and 88% were men. The mean degree of stenosis was 76.4 ± 11.2%. Sixty percent of the patients were symptomatic; 80% had hypertension, and the mean ejection fraction was 73.1%. Balloon dilation and stent placement were successful in all patients. Stenosis decreased from a median of 72.7% before to a median 4.7% after CAS. All 15 patients were followed for a mean of 11 months (range, 4 to 32 months). No new neurologic symptoms caused by the lesion appeared in any of the patients during the follow-up period. Follow-up angiography, which was performed on 15 patients at a mean of 8.8 months (2 to 28 months) after CAS, showed that the 15 lesions remained unchanged (100%). However, in-stent restenosis was observed in 1 lesion; as a result, angioplasty was required. Stent-induced kinking was observed in 8 patients, and it continues to demonstrate the same shape at follow-up angiograms. No new ischemic lesions were detected in any of the 15 patients who underwent MR imaging at a mean of 10 months (range, 2 to 32 months). The number of patients with the incomplete stent apposition tended to be lower with the SMART stent than with the Wallstent (approximately 10.3 [3/28] and 11.2% [12/107] respectively), but this difference is not significant (P = .79).

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics and follow-up results of 15 patients with an incomplete stent apposition at the stent edge

| Patient No./Age (y)/Sex | R/L | Location of Lesion | Follow-up DSA (mo) | Rate of Stenosis (%) | Stent | Stent-induced Kinking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/73/M | R | Proximal | 4 | 80 | Wallstent | + |

| 2/58/M | R | Proximal | 25 | 90 | Wallstent | |

| 3/77/M | L | Proximal | 4 | 60 | Wallstent | + |

| 4/61/M | R | Proximal | 18 | 84 | Wallstent | + |

| 5/77/M | L | Proximal | 7 | 70 | SMART | |

| 6/72/M | L | Proximal | 7 | 75 | SMART | + |

| 7/78/M | R | Proximal | 13 | 70 | SMART | |

| 8/69/M | L | Distal | 2 | 90 | Wallstent | |

| 9/60/M | L | Distal | 5 | 74 | Wallstent | + |

| 10/81/M | R | Distal | 4 | 90 | Wallstent | + |

| 11/80/M | L | Distal | 5 | 68 | Wallstent | |

| 12/81/M | R | Distal | 4 | 60 | Wallstent | |

| 13/73/F | R | Distal | 6 | 70 | Wallstent | + |

| 14/76/F | R | Distal | 3 | 95 | Wallstent | + |

| 15/66/M | R | Distal | 28 | 70 | Wallstent |

Note:—R indicates right; L, left; DSA, digital subtraction angiography.

Discussion

In our series, an incomplete stent apposition at the stent edge showed no change in shape in any of the lesions that underwent angiography within a mean time of 8.8 months after CAS. In addition, no ischemic events occurred as a result of the lesions in any of the 15 patients for a mean follow-up time of 11 months. We considered that clot formation outside the proximal edge of the stent might possibly occur after CAS because of the stasis of the blood flow in the space between the stent and the vessel wall. The stent struts might entrap emboli coming into the cerebral blood flow from outside the stent.3,6 Ischemic stroke might also be expected because of the clots in the space. As a result, we prescribed antiplatelet drugs after CAS to prevent clot formation outside the stent. Clot formation outside a stent is accelerated by the decreasing of turbulent flow caused by the decreased blood flow velocity at the stenotic lesion by stent placement.7,8 According to the results of the follow-up digital subtraction arteriography, as long as the stent showed no change or migration, no significant clot formation or neointimal hyperplasia was seen. Combination therapy with aspirin and a thienopyridine drugs (ticlopidine or clopidogrel) has come to be used for patients undergoing vascular stent placement because their additive effects through different pathways provide more substantial benefit than any single drug therapy.9,10 Therefore, a low-dose combination of aspirin (81 mg) and ticlopidine (200 mg) is usually used at our institute for patients at high risk for ischemic stroke and patients after CAS.11,12 In this study, our choice of antiplatelet therapy is therefore considered to be effective for preventing thromboembolic strokes and restenosis.

Conclusion

The existence of a segment of incomplete stent apposition had no adverse morphologic or clinical effect.

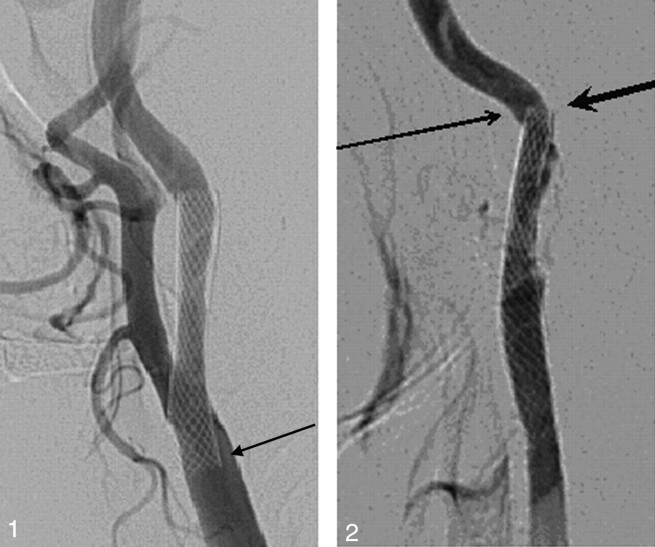

Fig. 1.

Patient 5. An asymptomatic 77-year-old man. A left carotid angiogram (lateral view) showing an incomplete stent apposition at the proximal stent edge (arrow).

Fig. 2.

Patient 9. A 60-year-old man with transient ischemic attacks. A left carotid angiogram revealing an incomplete stent apposition at the distal stent edge (small arrow) and stent-induced kinking (large arrowhead).

References

- 1.Fox DJ Jr, Moran CJ, Cross DT 3rd, et al. Long-term outcome after angioplasty for symptomatic extracranial carotid stenosis in poor surgical candidates. Stroke 2002;33:2877–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shawl F, Kadro W, Domanski MJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of elective carotid artery stenting in high-risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:1721–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka N, Martin JB, Tokunaga K, et al. Conformity of carotid stents with vascular anatomy: evaluation in carotid models. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:604–07 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohyama S, Kazekawa K, Iko M, et al. Spontaneous improvement of peristent ulceration after carotid artery stenting. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:151–56 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagata S, Kazekawa K, Aikawa H, et al. Hemodynamic stability under general anesthesia in carotid artery stenting. Radiat Med 2005;23:427–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkfeld J, Martin JB, Theron JG. Complications of carotid angioplasty and stenting. Neurosurg Focus 1998;5:1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohyama M, Mizushige K, Ohyama H, et al. Carotid turbulent flow observed convergent color Doppler flowmetry in silent cerebral infarction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2002;18:119–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orlandi G, Fanucchi S, Fioretti C, et al. Characteristics of cerebral microembolism during carotid stenting and angioplasty alone. Arch Neurol 2001;58:1410–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbert JM, Bernat A, Samama M, et al. The antiaggregating and antithrombotic activity of ticlopidine is potentiated by aspirin in the rat. Thromb Haemost 1996;76:94–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller C, Roskamm H, Neumann FJ. A randomized comparison of clopidogrel and aspirin versus ticlopidine and aspirin after the placement of coronary artery stents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:969–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatt DL, Bertrand ME, Berger PB, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized and registry comparisons of ticlopidine with clopidogrel after stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002;324:71–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]