Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Identification of the motor strip on MR imaging studies is difficult in the presence of mass effect and vasogenic edema because sulcal landmarks are obscured. We hypothesize that a difference in cortical thickness between the motor and sensory strips is readily apparent on T2-weighted images in the presence of vasogenic edema and reliably identifies the central sulcus.

METHODS: Thirteen patients with brain tumors resulting in vasogenic edema near the central sulcus were identified. The cortical thickness of the anterior and posterior banks of the central sulcus as well as the neighboring sulci in the frontal and parietal lobes were measured from T2-weighted images. Similar measures were obtained from neighboring sulci in the frontal and parietal lobes. Location of the central sulcus was confirmed with standard anatomic landmarks in all patients and by intraoperative cortical mapping in 2 patients.

RESULTS: A twofold difference in cortical thickness between the anterior and posterior banks of the central sulcus uniquely identified the central sulcus on T2-weighted images in the presence of vasogenic edema, despite the marked distortion of sulcal anatomy as a result of mass effect. This relationship was not present in neighboring sulci.

CONCLUSION: Cytoarchitectonic differences in the motor and sensory cortices result in a markedly thicker posterior than anterior bank of the central sulcus that is readily visible on routine T2-weighted images in the presence of vasogenic edema. Therefore, the cortical thickness can serve as a complementary method in identification of the motor strip in patients with mass effect.

Localization of the primary motor cortex is essential before brain tumor resection. Direct cortical stimulation remains the “gold standard” but is an invasive technique that is associated with the expected risks of craniotomy and cortical electrode placement. Because the relationship of primary motor cortex to the central sulcus is well known, many noninvasive methods for identifying the central sulcus have been investigated. These include sulcal anatomy, functional MR imaging, positron-emission tomography, and magnetoencephalography.1–5 Despite advances in technology, no single noninvasive method has proved to be 100% accurate in identifying the central sulcus.

Prior gross anatomic studies have demonstrated that the motor cortex (which lies in the anterior bank of the central sulcus) is approximately twice as thick as the sensory cortex (which lies in the posterior bank of the central sulcus).6, 7 This difference in thickness is readily demonstrable on high-resolution, T1-weighted, inversion recovery MR images. Using this technique, the thickness of the anterior bank of the central sulcus was measured to be approximately 1.5 times that of the posterior bank.6

Vasogenic edema is, by definition, restricted to the extracellular space. The white matter morphologically consists of a loose extracellular space, compared with the gray matter which has a higher cell attenuation. Vasogenic edema, therefore, is almost exclusively limited to the white matter, where there is less resistance to bulk flow.8 When mass effect and edema accompany an intracranial mass, the T1-weighted images may be less reliable due to obscuration of sulcal landmarks and loss of gray-white differentiation. However, in this situation, cortical thickness is clearly depicted on T2-weighted images, because the intrinsic T2 lengthening associated with the vasogenic edema significantly improves gray-white differentiation. In this study, we sought to determine whether a thickness difference between the sensory and motor cortices could be readily visualized on routine T2-weighted sequences, which in turn could provide a quick, reliable localization of the central sulcus in the presence of architectural distortion.

Methods

Thirteen consecutive patients with vasogenic edema as a result of lesions in the frontal and parietal lobes were retrospectively identified from the clinical caseload. MR imaging was performed at either 1.5T or 3T. T2-weighted axial sections parallel to the anterior commissure-posterior commissure plane were obtained with the following parameters: matrix size 384 × 256, interpolated to 512 × 512; 22-cm field of view (0.43 mm in plane resolution), 5-mm section thickness, and 0-mm intersection gap. Linear cortical thickness measures were obtained with the use of digital calipers on a PACS workstation. A single radiologist measured the T2-weighted images, which were magnified and windowed to optimize gray-white delineation. Measurements of cortical thickness were made perpendicular to and on opposing banks of sulci that were well delineated by vasogenic edema. The central sulcus and the neighboring frontal and parietal sulci were evaluated based on the pattern of vasogenic edema, so that not all sulci were evaluated in each patient. Neighboring frontal sulci included the precentral sulcus, superior frontal sulcus, and inferior frontal sulcus. Neighboring parietal sulci included the postcentral sulcus, intraparietal sulcus, and the ascending ramus of the cingulate sulcus. The central sulcus was evaluated in all but one patient in whom the edema was isolated to the frontal lobe; therefore, the cortical thickness of the motor strip could not be ascertained. The central sulcus and up to 4 additional sulci were evaluated in the other 12 patients. From 12 to 76 paired measurements were obtained in each patient. A total of 200 measurements (400 data points) was obtained across the central sulcus for all patients. A total of 88 (176 data points) and 120 (240 data points) measurements were obtained across approximately 10 frontal and 17 parietal sulci, respectively. Location of the central sulcus was confirmed using standard anatomic landmarks in all cases and with intraoperative cortical mapping in 2 patients. For the 2 cases confirmed intraoperatively, the radiologist reviewing the MR imaging was blinded to the surgical results. Average cortical thickness was calculated for individual patients based on measurements from the anterior and posterior banks of the central sulcus, and opposing banks of frontal and parietal sulci. When the sulcus was oriented in the anterior to posterior plane (ie, superior frontal sulcus), lateral to medial bank ratios were obtained.

For the purpose of statistical analysis, the anterior and lateral banks of frontal and parietal sulci were compared with the posterior and medial banks. Measurements were averaged within each subject and statistical analysis (paired t test) was performed across subjects.

Results

Differential cortical thickness across the central sulcus was readily visible on T2-weighted sequences in the presence of vasogenic edema (Fig 1). Minimal difference in cortical thickness was observed across neighboring parietal and frontal sulci (Fig 1). This visual impression was confirmed by direct measurement. Identification of the central sulcus was obscured on the corresponding T1-weighted images because of mass effect and sulcal effacement (Figs 2 and 3).

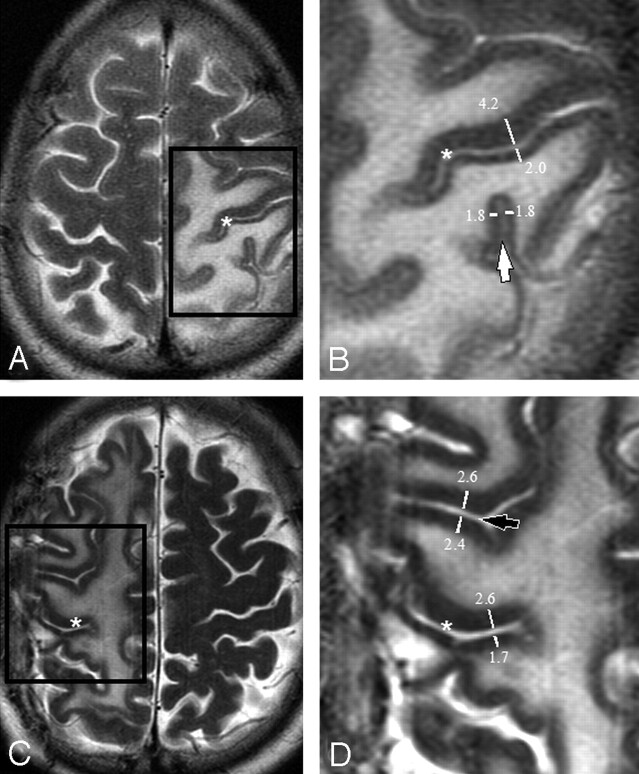

Fig 1.

Axial T2-weighted images showing edema surrounding the central sulcus (asterisks A–D) in 2 patients (A and C). Magnification of the boxed regions (B and D) demonstrate thickness measurements across the central sulcus (asterisks in B and D), across a neighboring parietal sulcus (a ramus of the intraparietal sulcus [white arrow]) and across a neighboring frontal sulcus (precentral sulcus [black arrow]). Only one measurement is shown for clarity. Up to 8 measurements were made along the length of the sulcus on each axial image. Note that measurements were performed perpendicular to the sulcus, ensuring that the ratio will not be affected by section orientation.

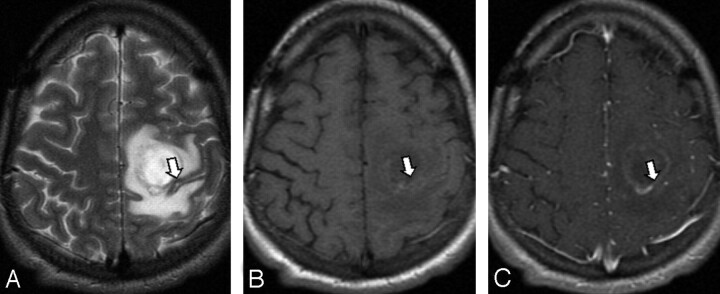

Fig 2.

A metastasis adjacent to the motor strip (arrow), confirmed by intraoperative cortical mapping. The motor cortex is thicker than the sensory cortex on T2-weighted imaging (A). This is not apparent on T1-weighted precontrast (B) and postcontrast (C) images in which the sulci are effaced.

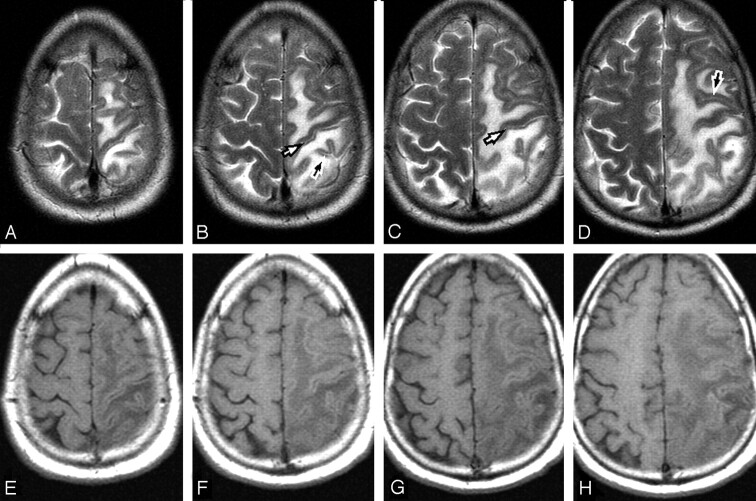

Fig 3.

Contiguous axial T2-weighted (A–D) and corresponding T1- weighted (E–H) images in a patient with vasogenic edema. The T2-weighted images exquisitely demonstrate the cortical thickness difference between the precentral and postcentral gyrus (white arrows) because the vasogenic edema outlines the cortex. These findings are only partially visible on the T1-weighted images. There is no discernible difference in cortical thickness of the anterior and posterior bank of sulci in the frontal and parietal lobes (black arrows).

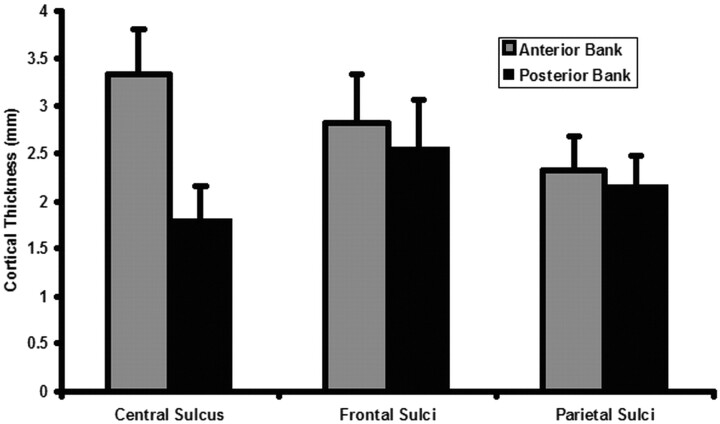

Cortical thickness measurements are summarized in Fig 4. The average cortical thickness of the precentral gyrus (motor strip) was 3.34 ± 0.46 mm (mean ± SD, n = 12 patients). The average cortical thickness of the postcentral gyrus (sensory strip) was 1.80 ± 0.36 mm (n = 12). The ratio of anterior to posterior bank cortex of the central sulcus was 1.98 ± 0.36 (n = 12).

Fig 4.

Box plot demonstrates an approximate 2:1 ratio of precentral to postcentral sulcus cortical thickness. The ratio of anterior/lateral to posterior/medial bank cortex of frontal and parietal sulci approaches 1:1.

The average thickness of the anterior/lateral bank cortex of frontal sulci was 2.82 ± 0.48 mm (n = 7). The average thickness of the posterior/medial bank cortex of frontal sulci was 2.56 ± 0.51 mm (n = 7). The ratio of anterior/lateral to posterior/medial bank cortex of frontal sulci was 1.12 ± 0.08 (n = 7). The average thickness of the anterior/lateral bank cortex of parietal sulci was 2.33 ± 0.35 mm (n = 8). The average thickness of the posterior/medial bank cortex of parietal sulci was 2.16 ± 0.32 mm (n = 8). The ratio of anterior/lateral to posterior/medial bank cortex of parietal sulci was 1.09 ± 0.07 (n = 8).

There was a statistically significant difference between the cortical thickness ratio across the central sulcus versus both frontal and parietal sulci (P < .001). Although there was a statistically significant difference between the anterior/lateral and posterior/medial bank of frontal and parietal sulci (P = .01 and P = .02, respectively), the thickness difference was approximately 10% in contrast to the nearly 100% difference across the central sulcus. The thickness difference across parietal and frontal sulci was not readily identifiable on routine visual inspection.

Discussion

Preoperative localization of the motor strip is essential before brain tumor resection. Precise location of the motor cortex is compromised in the presence of mass effect and edema because normal surface landmarks are obscured. When this occurs, additional methods for identifying the central sulcus must be used.

Prior gross anatomic studies have shown that the cortex of the precentral gyrus measures approximately 3.01–3.94 mm, whereas the cortex of the postcentral gyrus measures approximately 1.56–1.82 mm.6,7 Despite this variation in the cortical thickness measurement, the ratio between the anterior and posterior bank of the central sulcus was relatively constant, ranging between 1.9 and 2.1 in those anatomic studies. Surrounding sulci (eg, those of the frontal and parietal lobes) did not demonstrate a significant difference in cortical thickness.6

A prior study by Meyer et al6 used axial T1-weighted turbo inversion recovery images to demonstrate that, in normal volunteers, the motor cortex could easily be distinguished from the sensory cortex by visual confirmation of thickness differences. In that study, the motor cortex measured approximately 2.7 mm and the sensory cortex measured approximately 1.8 mm (a ratio of approximately 1.5).6 It is noteworthy that the ratio between the anterior and posterior banks of the central sulcus was approximately 2.0 in our study, more closely approximating the gross anatomic data. This large ratio should result in easier visual confirmation of the central sulcus in the presence of vasogenic edema. There may be discrepancies between the inversion recovery data and our study because (1) intrinsic signal intensity differences between T1- and T2-weighting may demarcate the gray-white boundary differently and (2) mass effect may stretch and differentially thin or thicken surrounding cortex.

It is essential to understand multiple different methods for locating the central sulcus, especially when mass effect and edema may distort normal anatomy. Multiple techniques may be needed to accurately localize the central sulcus, to include knowledge of surface landmarks, functional MR imaging, positron-emission tomography, and magnetoencephalography. Although effective in central sulcus localization, the latter 3 methods add both time and expense to the diagnostic evaluation, which may prevent routine clinical application. We have shown that routine T2-weighted axial images may reliably demonstrate this cortical thickness difference in the presence of vasogenic edema. It is unique to the central sulcus in that surrounding sulci do not demonstrate this phenomenon. The cortical thickness difference between the precentral and postcentral gyrus allows for simple visual confirmation of the motor strip, particularly when the normal surface architecture near the Rolandic fissure is obscured by mass effect. This may prove to be a valuable complementary method to identify the central sulcus without the application of advanced imaging techniques.

Conclusion

Although multiple noninvasive methods exist for evaluating the location of the central sulcus, none has proved to be 100% sensitive or specific. Identification of the central sulcus via cortical thickness has been previously validated in both anatomic studies and with MR imaging using high resolution, T1-weighted turbo inversion recovery sequences. The cortical thickness difference between the sensory and motor cortex corresponds with proved cytoarchitectonic differences between these cortical areas. As such, the cortical thickness difference seen in the presence of edema on T2-weighted images is an indicator of the central sulcus when its normal topography and surface landmarks are obscured by mass effect.

Footnotes

This work was initially presented in poster format at the 43rd annual ASNR Meeting, 2005 May 21–27, Toronto, Canada.

References

- 1.Yousry TA, Schmid UD, Alkadhi H, et al. Localization of the motor hand area to a knob on the precentral gyrus. Brain 1997;120:141–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzales-Portillo G. Localization of the central sulcus. Surg Neurol 1996;46:97–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Towle VL, Khorasani L, Uftring S, et al. Noninvasive identification of human central sulcus: a comparison of gyral morphology, functional MRI, dipole localization and direct cortical mapping. NeuroImage 2003;19:684–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimizu H, Nakasato N, Mizoi K, et al. Localizing the central sulcus by functional magnetic resonance imaging and magnetoencephalography. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1997;99:235–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bittar RG, Olivier A, Sadikot AF, et al. Presurgical motor and somatosensory cortex mapping with functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography. J Neurosurg 1999;91:915–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer JR, Roychowdhury S, Russell EJ, et al. Location of the central sulcus via cortical thickness of the precentral and postcentral gyri on MR. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996;17:1699–706 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blinkov SM, Glezer II. The human brain in figures and tables; a quantitative handbook. New York: Plenum Press;1968. :384

- 8.Thapar K, Rutka JT, Laws Jr ER. Brain edema, increased intracranial pressure, vascular effects, and other epiphenomena of human brain tumors. In: Kay AH, Laws Jr ER, eds. Brain tumors: an encyclopedic approach. New York: Churchill Livingstone;1995. :163–89