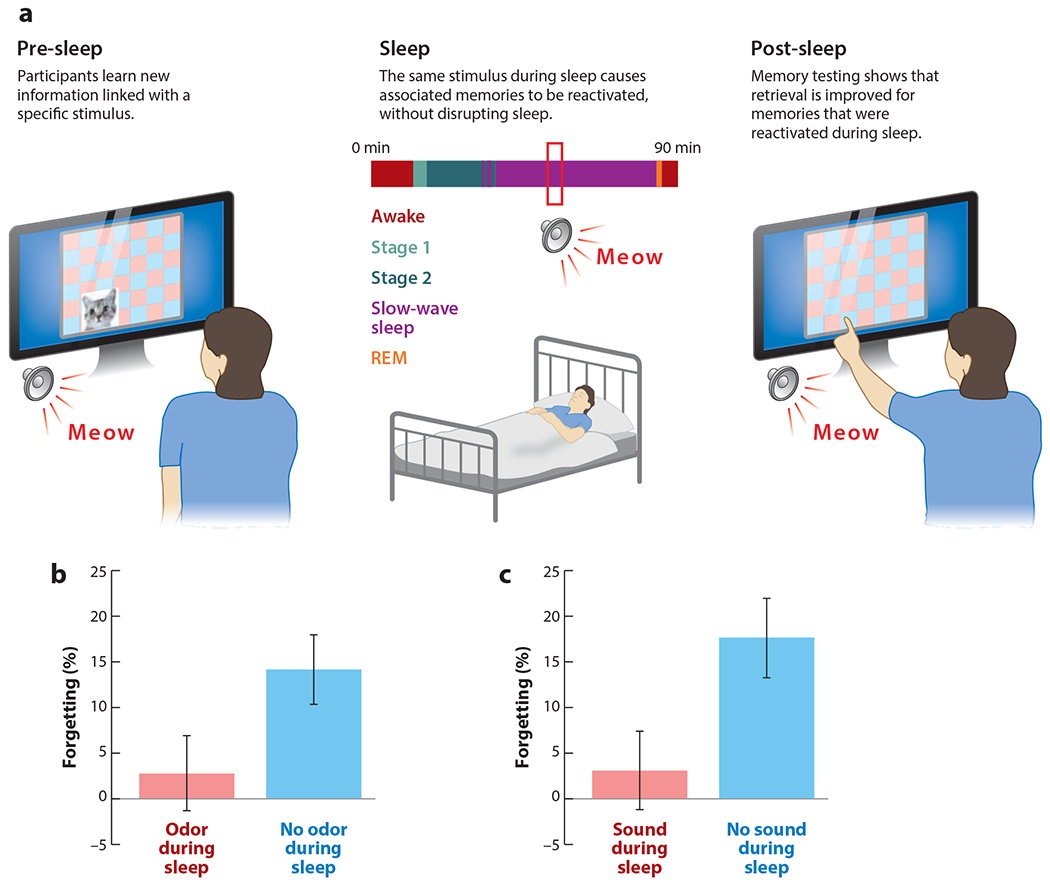

Figure 2.

(a) Targeted memory reactivation experiments generally include three phases. In the first phase (pre-sleep), participants acquire some new information. This information is coupled with stimuli that are included either as background context or as part of the learning (e.g., a meow sound paired with the spatial location of a cat image). In the second phase (sleep), these stimuli are unobtrusively presented during sleep. In the third phase (post-sleep), memory is tested after sleep. (b) In the experiment of Rasch et al. (2007), spatial learning of 15 objects, each shown in two locations on a 5 × 6 grid, was accomplished while a rose odor was present. Next, during an overnight sleep session with polysomnographic monitoring, the odor or an odorless vehicle was presented during sleep. Finally, spatial memory was assessed the next morning. The results showed relatively better recall when the odor had been presented during slow-wave sleep compared to when it had not. This memory effect was not observed when odors were presented during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep or when the memory test was one of motor learning instead. (c) In the experiment of Rudoy et al. (2009), spatial learning of 50 objects shown in random locations on a grid was accomplished while sounds were presented. For each object, a matching sound was used. Next, during an afternoon nap with polysomnographic monitoring, half of the sounds were presented at a low intensity. Finally, spatial memory was assessed when participants attempted to place each object at precisely the correct screen location. The results showed relatively better memory performance for objects if corresponding sounds had been presented during slow-wave sleep than if not. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.