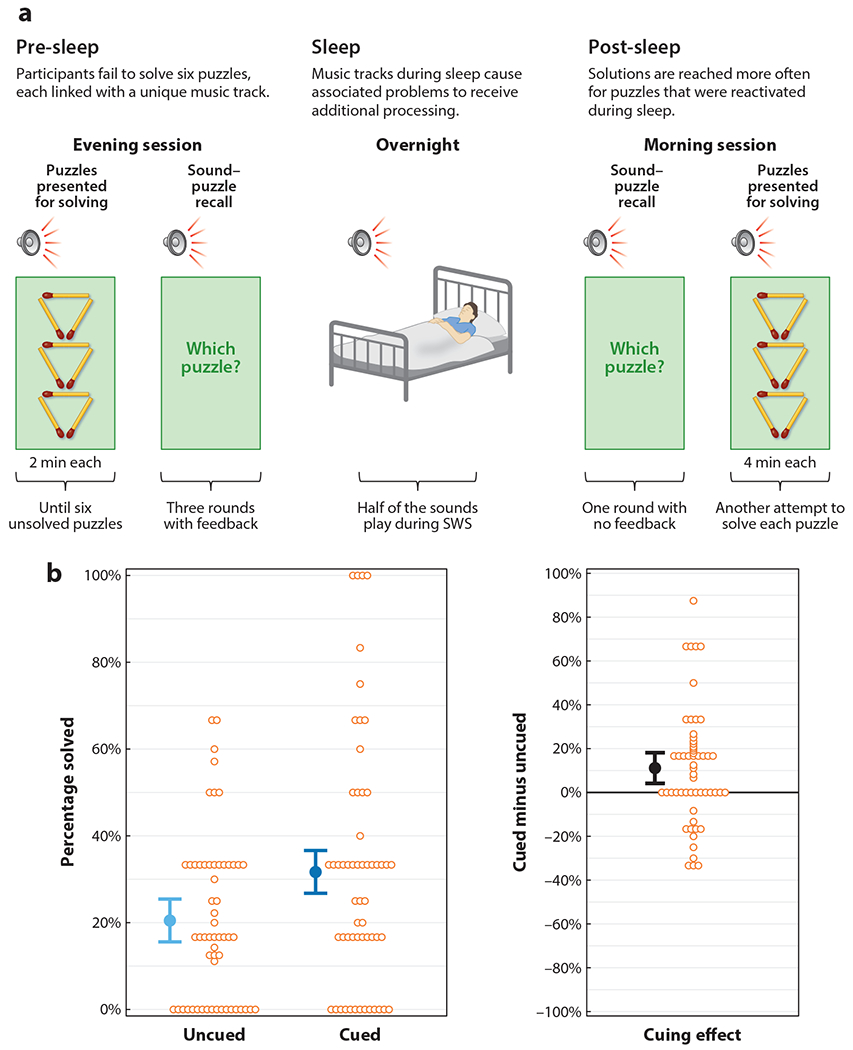

Figure 3.

Experimental design and results from Sanders et al. (2019). (a) The participants attempted to solve a set of challenging puzzles (including matchstick, spatial, verbal, and rebus puzzles). Each puzzle was presented together with an arbitrary musical theme or sound, and participants were required to master these associations. The pre-sleep learning phase of the experiment ended when there were six puzzles that could not be solved in the 2 minutes allotted for working on each one. Participants slept in their own homes using a wireless sleep-monitoring device linked to a computer, which covertly presented sounds when slow-wave sleep (SWS) was detected. In this way, three of the six unsolved puzzles were reactivated using the corresponding sounds. The matchstick puzzle shown as an example came with instructions to move three matchsticks to create four equilateral triangles. (b) The results obtained the next day confirmed that memory reactivation had the predicted effect: When participants attempted to solve the same six puzzles, solving rates were higher for cued puzzles than for uncued puzzles. In the left panel, each orange circle represents a single participant’s success rate for one type of puzzle. The blue circles represent the average for each condition. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The right panel shows the difference between the two conditions similarly. Figure adapted from Sanders et al. (2019).