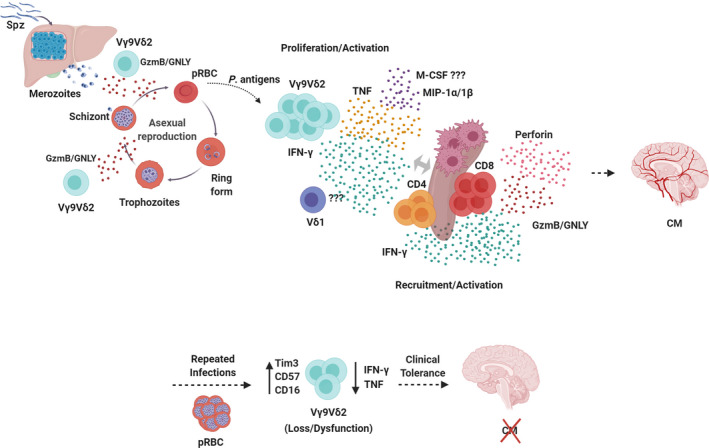

Fig. 1.

Functional activities of human γδ T cells in malaria. Infected Anopheles mosquitoes inject Plasmodium Spz into the host skin from where they migrate to the liver and invade hepatocytes to develop into schizonts containing thousands of merozoites. Merozoites then egress from hepatocytes and are released into the bloodstream where they invade red blood cells and initiate the blood‐stage infection, when clinical symptoms of malaria, such as CM, appear. Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are able to control/inhibit parasite replication by targeting and killing extracellular merozoites and intracellular late‐stage parasites though granulysin (GNLY)‐mediated release of cytotoxic granzymes (GzmB) during the intraerythrocytic stage. Vγ9Vδ2 T cells recognize soluble phosphoantigens released from schizont stage parasites and, potentially, other pRBC stages, and become activated, producing pro‐inflammatory cytokines, like IFN‐γ and TNF, and chemokines, like MIP‐1α and MIP‐1β. This promotes splenic activation and differentiation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells into Th1, IFN‐γ‐producing, and cytotoxic cells, and subsequent migration to the brain, where they cause neuroinflammation and, ultimately, CM. However, after repeated parasite exposure, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells may increase expression of immunoregulatory molecules, such as Tim‐3, and decrease production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, which associates with clinical tolerance.