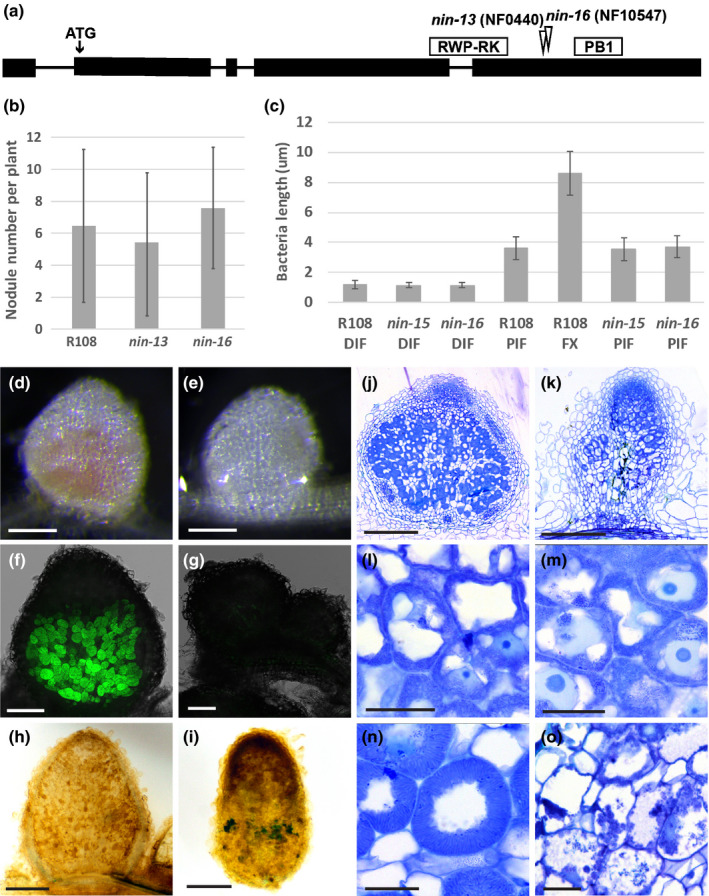

Fig. 3.

Phenotype of Medicago nin‐13 and nin‐16 mutants. (a) Schematic representation of the Tnt1 insertion site in nin‐13 and nin‐16 alleles. Exons of NIN are shown as black boxes, and introns are represented by lines. (b) The number of nodules formed on R108 (wild‐type), nin‐13 and nin‐16 are similar. Nodule numbers per plant (n = 19) were counted at 2 wk post inoculation (wpi). Data are means ± SD. (c) Rhizobia in nin‐13/16 were able to elongate to the size that in wild‐type plants reached before the transition to the fixation zone. Bacteria length are measured at 2 wpi. n 70, data are means ± SD. DIF, distal part of infection zone; PIF, proximal part of infection zone; FX, fixation zone. At 2 wpi with Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011, wild‐type nodules were pink (d) whereas nin‐16 nodules remained white (e) that indicate the absence of leghaemoglobin. Formation of nonfunctional nodules on nin‐16 was further confirmed by inoculation with Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011 carrying the PronifH::GFP reporter construct (f, g). nifH was highly induced in R108 (f) but not induced in nin‐16 nodules (g). Semithin sections stained with toluidine blue show that in comparison with wild‐type nodules (j, l, n), an apical meristem was formed on nin‐16 mutant nodule (k), rhizobia were released and divided (m), however, their development was arrested, and premature senescence was induced (o). Potassium permanganate/methylene blue staining shows accumulation of phenolic compound in nin‐16 nodule (i), but not in wild‐type nodule (h). nin‐13 shows similar phenotype as nin‐16, figures shown in Supporting Information Fig. S3. Bars: (d, e) 2 mm; (f, g) 200 µm; (h, i) 500 µm; (j, k) 300 µm; (l–o) 30 µm.