Abstract

Background

To stratify the prognosis of patients with programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) ≥ 50% advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (aNSCLC) treated with first-line immunotherapy.

Methods

Baseline clinical prognostic factors, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), PD-L1 tumour cell expression level, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and their combination were investigated by a retrospective analysis of 784 patients divided between statistically powered training (n = 201) and validation (n = 583) cohorts. Cut-offs were explored by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and a risk model built with validated independent factors by multivariate analysis.

Results

NLR < 4 was a significant prognostic factor in both cohorts (P < 0.001). It represented 53% of patients in the validation cohort, with 1-year overall survival (OS) of 76.6% versus 44.8% with NLR > 4, in the validation series. The addition of PD-L1 ≥ 80% (21% of patients) or LDH < 252 U/l (25%) to NLR < 4 did not result in better 1-year OS (of 72.6% and 74.1%, respectively, in the validation cohort). Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 2 [P < 0.001, hazard ratio (HR) 2.04], pretreatment steroids (P < 0.001, HR 1.67) and NLR < 4 (P < 0.001, HR 2.29) resulted in independent prognostic factors. A risk model with these three factors, namely, the lung immuno-oncology prognostic score (LIPS)-3, accurately stratified three OS risk-validated categories of patients: favourable (0 risk factors, 40%, 1-year OS of 78.2% in the whole series), intermediate (1 or 2 risk factors, 54%, 1-year OS 53.8%) and poor (>2 risk factors, 5%, 1-year OS 10.7%) prognosis.

Conclusions

We advocate the use of LIPS-3 as an easy-to-assess and inexpensive adjuvant prognostic tool for patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% aNSCLC.

Key words: non-small-cell lung cancer, immunotherapy, PD-L1, LDH, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, steroids, performance status, immune-checkpoint inhibitor, prognostic

Highlights

-

•

Immunotherapy/chemoimmunotherapy combinations are currently not superior to immunotherapy alone for high PD-L1 aNSCLC.

-

•

NLR with a cut-off of 4 was validated as an independent prognostic factor for immunotherapy in high PD-L1 aNSCLC.

-

•

The addition of either PD-L1 ≥ 80% or LDH < 252 U/l to NLR < 4 did not result in better prognostic stratification.

-

•

The LIPS-3 is a validated 3-class prognostic classification based on the NLR, ECOG PS and pretreatment steroids.

-

•

The LIPS-3 is a routinely assessable adjuvant prognostic tool for high PD-L1 aNSCLC patients.

Introduction

Patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (aNSCLC) and programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) tumour cell expression ≥50% can be currently treated with first-line pembrolizumab monotherapy,1 which has demonstrated a 3-year overall survival (OS) rate of 43.7%, compared with 24.9% with chemotherapy, and more durable tumour responses in selected patients.2 However, this choice is currently being challenged by the addition of chemotherapy to immunotherapy,3 by adding a second immune-checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)4 or by combining both strategies.5 Thus, prognostic and predictive biomarkers to identify patients who need treatment escalation or a different therapeutic strategy are needed.6,7

Neutrophils are related to polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). MDSCs comprise a heterogeneous group of myeloid cells that suppress immune responses by hindering T-cell proliferation and expansion.8 Their serum concentration rises in the presence of a tumour and is associated with a poorer prognosis.9 The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) includes quantitative variations of both the neutrophils and the lymphocytes, which are the two most relevant immune cell populations participating in immune responses.10 It is a surrogate for tumour-associated inflammation and the activity of MDSCs. Several studies support the association between elevated NLR and poor prognosis in cancer,10 specifically NSCLC.11,12 Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a potential inflammatory biomarker in patients with cancer and has shown a correlation with poor outcomes in several cancers.11,13

The utility of PD-L1 expression on cancer cells as a predictive and prognostic biomarker remains controversial because of the existence of various PD-L1 antibodies, scoring systems and positivity cut-offs.14 The predictive value of PD-L1 ≥ 50% by 22C3 Dako pharmDx immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay has been confirmed by the superiority of the first-line single-agent pembrolizumab over chemotherapy in patients with aNSCLC.2,15 Furthermore, better outcomes have been reported among patients treated with first-line pembrolizumab whose tumours very highly expressed PD-L1 (i.e. ≥90%) by different IHC antibodies and platforms.16 Combinations of NLR with LDH11,17 or PD-L112 may improve the prognostic value of each of them among patients receiving ICIs in aNSCLC.

In our large, real-world series18,19 of patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% (assessed by different IHC assays) aNSCLC treated with first-line pembrolizumab, we aimed to confirm the prognostic value of NLR and its combination with PD-L1 or LDH, or other baseline clinical factors. The following analysis is reported following the REMARK Guideline.20

Material and methods

The study objectives were (i) the validation of baseline NLR and its combination with the PD-L1 tumour cell expression level or the blood LDH value as prognostic tools; (ii) the prognostic stratification of patients by a combination of independent clinical and laboratory prognostic factors with the final output of a three-category (favourable, intermediate and poor-risk) prognostic classification.

For this analysis, the dataset included patients aged >18 years, with histologically confirmed aNSCLC, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) ≤2, PD-L1 tumour cells expression ≥50% using a variety of immunohistochemical antibodies and platforms depending on local institutional practice and treated with first-line pembrolizumab in 32 European centres (29 in Italy, 1 in the UK, 1 in Switzerland and 1 in The Netherlands).

For the first study objective, the dataset was divided between a training and validation cohort. To size the training cohort, we assumed a 10% difference in the probability of 2-year OS predicted by baseline NLR compared with that of the overall population. Based on an expected 2-year OS of 52%,12 at least 193 patients were required to predict a 2-year OS ≥ 62% in patients with low and ≤42% in those with high baseline NLR, with 80% power and one-sided α of 0.05. The training cohort included patients from our previous five-centre-based series12 with the addition of patients from two centres picked from the main dataset to reach the required target sample size. The baseline NLR, or the ratio between absolute neutrophils and lymphocytes, and the LDH (in units/litre) were collected from reports of routine blood samples from within 7 days of treatment initiation and analysed by local laboratories. The information on PD-L1 tumour cells expression level was collected from the local assessment of tumour samples. The cut-offs for NLR, PD-L1, LDH and body mass index (BMI) were searched by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves considering progressive disease (PD) or disease response as events in the whole dataset. These cut-offs were then tested in the two training and validation cohorts. Before plotting the ROC curves, a correlation between PD and disease response with OS in the whole series of patients was checked. The combined biomarker analysis involved patients with available information for PD-L1 and LDH, with possible overlapping between higher PD-L1 and normal LDH cohorts. The prognostic value of NLR, PD-L1 and LDH on OS was assessed by the two-sided log-rank test with a significant difference of P < 0.05 in the training and validation cohorts.

For the second study objective, the following clinical parameters were assessed in the training and validation cohorts by two-sided log-rank tests with a significant difference of P < 0.05: histology (squamous versus nonsquamous), baseline ECOG PS (2 versus 0-1) and BMI (≥24.8 versus <24.8 kg/m2, cut-off based on ROC curve in PD—see Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100078), the use of pretreatment steroids (yes versus no) and the presence of brain (yes versus no) or liver metastases (yes versus no). A multivariate Cox-regression analysis on OS was performed on factors that were proven to be significant in univariate analysis and confirmed within the validation cohort. A risk model was built with independent prognostic factors, tested in the training and validation cohorts, following the rules of external validation21 and reported in the whole series. Cox proportional hazard regression was also used to compute the predicted probabilities for death according to the computed scores in both cohorts, to estimate Harrell's C statistic.

The OS was calculated from the date of treatment start until death or date of the last follow-up and was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, reported as medians with confidence limits [95% confidence interval (CI)] and compared using the two-sided log-rank test, with an acceptable significance value of P < 0.05. Patients who did not have events at the time of the analysis were censored.

Statistical significance was investigated by chi-square tests and Wilcoxon matched pair tests for dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively, with an acceptable significance value of P < 0.05.

Complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) and PD as the best response to the treatment were assessed in each centre based on the RECIST criteria version 1.1.22

The study was approved by the respective local ethical committees on human experimentation of each institution, after previous approval by the coordinating centre (Comitato Etico per le province di L'Aquila e Teramo, deliberation number 15 of 28 November 2019). All patients provided written, informed consent to treatment with immunotherapy. The procedures followed were in accordance with the precepts of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of 201 and 583 patients for the training and validation cohorts, respectively, are summarised in Table 1. Among baseline patient characteristics, a statistical difference was observed in age (P < 0.001) and BMI (P = 0.025) as continuous variables between the two cohorts. Patients started pembrolizumab between December 2016 and November 2019; the median follow-up was 13.2 months (95% CI 10.7-15.6) and 13.6 months (95% CI 12.3-14.8) for the training and validation cohorts, respectively.

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics and outcomes of training and validation cohorts

| Characteristic | Training (N = 201) | Validation (N = 583) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (range) | 69 (31-86) | 70 (28-92) | <0.001 |

| Sex, male/female, n (%) | 131 (65)/70 (35) | 388 (67)/195 (33) | 0.7217 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |||

| Never | 19 (10) | 54 (9) | 0.9362 |

| Current | 63 (32) | 205 (35) | 0.3917 |

| Former | 116 (59) | 324 (56) | 0.4604 |

| NK | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Histology, n (%) | |||

| Squamous | 53 (26) | 145 (35) | 0.6736 |

| Nonsquamous | 148 (74) | 438 (75) | |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 60 (30) | 203 (35) | 0.1982 |

| 1 | 108 (54) | 285 (49) | 0.2360 |

| 2 | 33 (16) | 95 (16) | 0.9676 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (range) | 24.5 (16.9-36.6) | 24.2 (14.0-45.0) | 0.0249 |

| NK, n (%) | 33 (16) | 13 (2) | |

| Brain metastases, n (%) | 31 (15) | 116 (20) | 0.1611 |

| Liver metastases, n (%) | 23 (11) | 76 (13) | 0.5576 |

| Pretreatment steroids, n (%) | 40 (20) | 145 (25) | 0.1524 |

| NLR, median (range) | 3.9 (0.6-28.0) | 3.8 (0.7-47.5) | 0.9928 |

| PD-L1, median (range) | 70 (50-100) | 70 (50-100) | 0.5459 |

| NK | 57 (28) | 189 (32) | |

| LDH, median (range) | 255 (123-1699) | 255 (72-2152) | 0.2684 |

| NK, n (%) | 81 (40) | 134 (23) | |

| PD-L1 IHC Ab, n (%) | |||

| 22C3 | 130 (65) | 355 (61) | 0.3408 |

| SP263 | 62 (31) | 210 (36) | 0.1838 |

| Other | 9 (4) | 18 (3) | 0.3513 |

| Best responseb, n (%) | |||

| CR/PR | 85 (49) | 229 (44) | 0.2448 |

| SD | 47 (27) | 133 (25) | 0.6797 |

| PD | 42 (24) | 161 (31) | 0.0946 |

| NA | 27 (13) | 60 (10) | 0.2215 |

| OS | |||

| 1 year-OS, median (range) | 60.5 (58.2-63.0) | 61.8 (60.5-63.2) | 0.451 |

| 2 year-OS, median (range) | 51.5 (49.1-54.1) | 47.1 (45.7-48.6) | |

| PFS, median (range) | 11.2 (7.5-14.8) | 8.7 (7.1-10.3) | 0.180 |

| Subsequent therapies, n (%) | 42 (21) | 124 (21) | 0.9109 |

Ab, antibody; BMI, body mass index; CR, complete response; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NK, not known; No, number; NA, not assessable; 1 year-OS, overall survival at 1 year; 2 year-OS, overall survival at 2 years; PD, progressive disease; PD-L1, programmed cell death-ligand 1; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Continuous variables were compared with the use of Wilcoxon two-sample test. Contingency tables were analysed by chi-square test. OS and PFS were assessed by two-sided log-rank tests. Statistically significant values are presented in bold.

By RECIST version 1.1 criteria.

NLR was available for all patients. The PD-L1 tumour cells expression level was >50% for all patients, but specific values were available for 144 (72%) and 394 (68%) and LDH for 120 (60%) and 449 (77%) patients in the training and validation cohorts, respectively.

Significant cut-offs for NLR and LDH by ROC curves on PD were 4.0 [area under the curve (AUC) 0.63, P < 0.0001] and 252.5 (AUC 0.58, P = 0.002), respectively (see Supplementary Figure S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100078). The PD-L1 tumour cells expression level cut-off of 77.5% was significant by ROC curves on CR/PR (AUC 0.56, P = 0.036; see Supplementary Figure S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100078). OS was significantly associated with disease response, with 1-year OS of 90.6% in patients with CR/PR, 71.5% in SD and 17.4% in PD (P < 0.001 for all group comparisons; see Supplementary Figure S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100078).

As the 2-year OS of the training cohort was 51.5% (95% CI 49.1-54.1), 64.2% (95% CI 60.2-68.4) and 39.5% (95% CI 36.9-42.4) for NLR < 4 and ≥ 4, respectively, the 10% difference in the probability of 2-year OS predicted by the baseline NLR compared with that of the overall population was met and the sample size of the training cohort was considered as adequate. NLR < 4 was a significant prognostic factor for OS in training and validation cohorts (P < 0.001 for both). The significant prognostic value showed by PD-L1 and LDH in the training cohort (P = 0.049 and P = 0.005, respectively) was not confirmed in the validation cohort (P = 0.669 and P = 0.094, respectively; see Supplementary Figure S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100078). In the validation cohort, NLR < 4 identified 53% of patients with 1-year OS of 76.6% versus 44.8% of those with NLR ≥ 4, (see Supplementary Figure S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100078). The addition of PD-L1 ≥ 80% or LDH < 252 U/l to NLR < 4 identified 21% and 25% of patients who did not show a better outcome than the NLR < 4 alone, with 1-year OS of 72.6 and 74.1, respectively, in the validation cohort; however, it identified an intermediate-risk group of patients showing a 1-year OS of 63.3% and 62.0%, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall survival by NLR plus PD-L1 or LDH in the training and validation cohorts.

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PD-L1, programmed cell death-ligand 1.

| Cohort (N) | Variable (n, %) | 1-year OS, % | 95% CI | P-value | HR [95% CI] (P-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Training (143) |

Favourable (NLR < 4, PD-L1 ≥ 80) (35, 24) Intermediate (other) (76, 53) Poor (NLR ≥ 4, PD-L1 < 80) (32, 22) |

74.4 60.2 39.1 |

67.6-81.6 56.2-64.5 35.2-43.4 |

0.00193a 0.0182b 0.0577c |

0.20 [0.08-0.51] (<0.001) 0.45 [0.24-0.85] (0.013) 1.0 |

| B Training (120) |

Favourable (NLR < 4, LDH < 252) (40, 33) Intermediate (other) (48, 40) Poor (NLR ≥ 4, LDH ≥ 252) (32, 27) |

80.4 65.4 38.6 |

73.8-87.3 40.3-70.8 35.2-42.4 |

<0.001a 0.0192b 0.105c |

0.48 [0.18-1.27] (0.141) 1.0 2.44 [1.21-4.91] (0.012) |

| C Validation (393) |

Favourable (NLR < 4, PD-L1 ≥ 80) (83, 21) Intermediate (other) (196, 50) Poor (NLR ≥ 4, PD-L1 < 80) (114, 29) |

72.6 63.3 40.9 |

68.6-76.8 61.0-65.8 38.9-43.1 |

<0.001a,b 0.0504c |

0.62 [0.38-1.00] (0.052) 1.0 1.93 [1.37-2.70] (<0.001) |

| D Validation (449) |

Favourable (NLR < 4, LDH < 252) (114, 25) Intermediate (other) (219-49) Poor (NLR ≥ 4, LDH ≥ 252) (116, 26) |

74.1 62.0 39.9 |

70.7-77.7 59.7-64.6 38.0-42.0 |

<0.001a,b 0.0267c |

0.63 [0.42-0.96] (0.033) 1.0 1.92 [1.39-2.66] (<0.001) |

a Favourable versus poor.

b Intermediate versus poor.

c Favourable versus intermediate.

By univariate analysis, significant clinical prognostic factors confirmed in the validation cohort were a baseline ECOG PS of 2 (P < 0.001), the use of pretreatment steroids (P < 0.001) and the presence of liver metastases (P = 0.034; Table 2). The multivariate analysis of clinical and laboratory significant prognostic factors, confirmed by the validation cohort, indicated three independent prognostic factors: a baseline ECOG PS of 2 [P < 0.001, hazard ratio (HR) 2.04], pretreatment steroids (P < 0.001, HR 1.67), a baseline NLR < 4 (P < 0.001, HR 2.29; Table 3). These three factors were available for all patients and the additional presence of each one of these allowed a prognostic stratification of OS in training and validation cohorts and the entire series (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis on overall survival of clinical baseline prognostic factors

| Variable | At risk | Events, n | 1-year OS, % | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training cohort | ||||

| Histology | ||||

| Squamous | 52 | 16 | 63.3 | 0.0683 |

| Nonsquamous | 148 | 56 | 59.6 | |

| ECOG PS | ||||

| 0-1 | 167 | 47 | 70.3 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 33 | 25 | 17.1 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| ≥24.8 | 73 | 16 | 74.6 | 0.022 |

| <24.8 | 94 | 36 | 59.2 | |

| Pretreatment steroids | ||||

| Yes | 40 | 23 | 37.1 | <0.001 |

| No | 161 | 49 | 64.9 | |

| Brain metastases | ||||

| Yes | 31 | 16 | 42.7 | 0.028 |

| No | 170 | 56 | 63.8 | |

| Liver metastases | ||||

| Yes | 23 | 12 | 42.6 | 0.029 |

| No | 178 | 60 | 62.8 | |

| Validation cohort | ||||

| Histology | ||||

| Squamous | 145 | 56 | 66.5 | 0.826 |

| Nonsquamous | 438 | 169 | 59.8 | |

| ECOG PS | ||||

| 0-1 | 488 | 167 | 66.3 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 95 | 58 | 37.4 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| ≥24.8 | 246 | 89 | 65.6 | 0.123 |

| <24.8 | 324 | 133 | 57.5 | |

| Pretreatment steroids | ||||

| Yes | 145 | 81 | 41.6 | <0.001 |

| No | 438 | 144 | 68.2 | |

| Brain metastases | ||||

| Yes | 116 | 44 | 60.3 | 0.710 |

| No | 467 | 181 | 61.8 | |

| Liver metastases | ||||

| Yes | 76 | 38 | 50.8 | 0.034 |

| No | 507 | 187 | 63.2 |

BMI, body mass index; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; OS, overall survival.

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Log-rank test.

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses for prognostic factorsa

| Covariate—single At baseline |

OS |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Validation cohort | |||

| ECOG PS 0-1 versus 2 | 2.04 | (1.50-2.76) | <0.001 |

| Steroids, yes versus no | 1.67 | (1.26-2.21) | <0.001 |

| NLR ≥ 4 versus < 4 | 2.29 | (1.72-3.05) | <0.001 |

| Liver metastases yes versus no | 1.18 | (0.83-1.68) | 0.364 |

CI, confidence interval; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; NLR, neutrophils-to-lymphocytes ratio; OS, overall survival.

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Multivariate analysis of significant factors in univariate analysis performed with the Cox proportional hazards model.

Figure 2.

Overall survival by combination score of three independent prognostic factors in the training and validation cohorts and all series.

| Cohort (N) | Variable (n, %) | 1-year OS, % | 95% CI | P-value | HR [95% CI] (P-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Training (197) |

0 risk factors (78, 40) 1 risk factors (76, 39) 2 risk factors (36, 18) 3 risk factors (7, 4) |

73.1 71.4 19.5 0.0 |

68.8-77.6 67.3-75.7 18.1-21.2 NA |

<0.001a nsb |

0.02 [0.01-0.06] (<0.001) 0.03 [0.01-0.08] (<0.001) 0.16 [0.07-0.38] (<0.001) 1.0 |

| B Validation (583) |

0 risk factors (239, 41) 1 risk factors (209, 36) 2 risk factors (100, 17) 3 risk factors (35, 6) |

79.8 57.1 41.5 12.9 |

77.5-82.2 54.9-59.5 39.4-43.8 12.2-13.8 |

<0.001c <0.05d |

0.10 [0.06-0.16] (<0.001) 0.21 [0.14-0.32] (<0.001) 0.31 [0.20-0.50] (<0.001) 1.0 |

| C All (784) |

0 risk factors (317, 40) 1 risk factors (289, 37) 2 risk factors (136, 17) 3 risk factors (42, 5) |

78.2 61.8 36.0 10.7 |

76.2-80.3 59.8-63.9 34.4-37.7 10.3-11.3 |

<0.001e | 0.08 [0.06-0.13] (<0.001) 0.16 [0.11-0.23] (<0.001) 0.32 [0.22-0.48] (<0.001) 1.0 |

Baseline risk factors: performance status ≥2, use of steroids, NLR ≥ 4.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not assessable; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; ns, not statistically significant; OS, overall survival.

a 0, 1, 2 versus 3; 0, 1 versus 2.

b 0 versus 1.

c 0, 1, 2, versus 3; 0 versus 1; 0 versus 2.

d 1 versus 2.

e For all group comparisons.

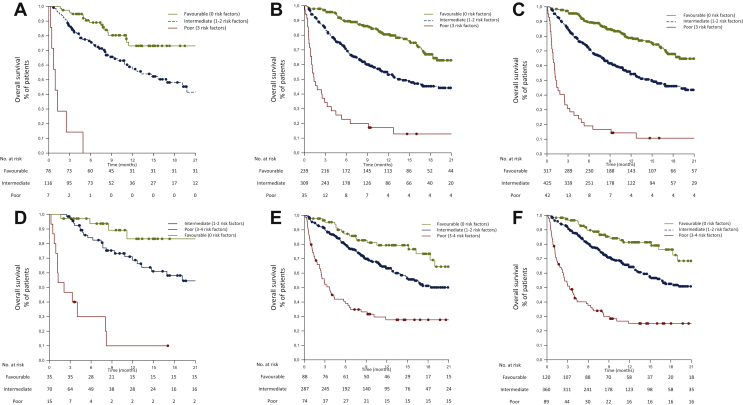

In a risk model including these three factors, namely, the Lung Immuno-oncology Prognostic Score (LIPS)-3, patient outcomes were stratified into three risk groups according to OS: favourable (0 risk factors), accounting for 40% of the whole series, with a 1-year OS of 78.2%; intermediate (1 or 2 risk factors), representing 54% of patients, with a 1-year OS of 53.8%; poor (>2 risk factors), representing 5% of patients, with a 1-year OS of 10.7% (Figure 3). Harrell's C statistic for OS of LIPS-3 in the training and validation cohorts was 0.65 (95% CI 0.58-0.72, P < 0.0001) and 0.66 (95% CI 0.62-0.69, P < 0.0001), respectively.

Figure 3.

Overall survival by classification score with LIPS-3 and LIPS-4 in the training, validation and all cohorts.

LIPS, Lung Immuno-oncology Prognostic Score; LIPS-3, based on the following three validated and independent prognostic factors: performance status ≥2, use of steroids and NLR ≥ 4; LIPS-4, LIPS-3 plus LDH.

| Cohort (N) | Variable (n, %) | 1-year OS, % | 95% CI | P-value | HR [95% CI] (P-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification by LIPS-3 | |||||

| A Training (201) |

Favourable: 0 risk factors (78, 39) Intermediate: 1-2 risk factors (116, 58) Poor: 3 risk factors (7, 3) |

73.1 55.6 0.0 |

68.8-77.6 52.8-58.7 NA |

<0.001a <0.05c |

0.03 [0.01-0.07] (<0.001) 0.06 [0.03-0.14] (<0.001) 1.0 |

| B Validation (583) |

Favourable: 0 risk factors (239, 41) Intermediate: 1-2 risk factors (309, 53) Poor: 3 risk factors (35, 6) |

79.8 52.5 12.9 |

77.5-82.2 50.9-54.3 12.2-13.8 |

<0.001d | 0.10 [0.06-0.16] (<0.001) 0.24 [0.16-0.36] (<0.001) 1.0 |

| C All (784) |

Favourable: 0 risk factors (317, 40) Intermediate: 1-2 risk factors (425, 54) Poor: 3 risk factors (42, 5) |

78.2 53.8 10.7 |

76.2-80.3 52.4-55.3 10.3-11.3 |

<0.001d | 0.08 [0.06-0.13] (<0.001) 0.20 [0.14-0.29] (<0.001) 1.0 |

| Classification by LIPS-4 | |||||

| D Training (120) |

Favourable: 0 risk factors (35-29) Intermediate: 1-2 risk factors (70, 58) Poor: 3-4 risk factors (15, 13) |

83.3 66.2 10.0 |

76.8-90.1 62.0-70.6 9.3-11.1 |

<0.001a nsb |

0.05 [0.02-0.16] (<0.001) 0.14 [0.07-0.28] (<0.001) 1.0 |

| E Validation (449) |

Favourable: 0 risk factors (88, 20) Intermediate: 1-2 risk factors (287, 64) Poor: 3-4 risk factors (74, 16) |

79.3 62.7 27.6 |

75.6-63.2 60.7-64.8 26.2-29.2 |

<0.001a <0.05c |

0.18 [0.11-0.30] (<0.001) 0.34 [0.24-0.47] (<0.001) 1.0 |

| F All (569) |

Favourable: 0 risk factors (120, 21) Intermediate: 1-2 risk factors (360, 63) Poor: 3-4 risk factors (89, 16) |

81.3 63.7 25.1 |

78.1-84.7 61.9-65.6 24.0-26.4 |

<0.001d | 0.14 [0.08-0.22] (<0.001) 0.30 [0.22-0.40] (<0.001) 1.0 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LIPS, Lung Immuno-oncology Prognostic Score; LIPS-3, based on the following three validated and independent prognostic factors: performance status ≥2, use of steroids, NLR ≥ 4; LIPS-4, LIPS-3 plus LDH; NA, not assessable; No., number of patients; ns, not statistically significant; OS, overall survival.

a Favourable, Intermediate versus Poor.

b Intermediate versus Poor.

c Good versus Intermediate.

d All group comparisons.

A risk model adding the baseline LDH [available for 569 patients (73%) in the whole series], namely, the LIPS-4, was explored. The addition of this fourth factor refined the prognostic stratification of OS in training and validation cohorts and the whole series (see Supplementary Figure S6, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100078). The following three risk groups according to the OS were obtained by the LIPS-4: favourable (0 risk factors), accounting for 21% of the whole series, with a 1-year OS of 81.3%; intermediate (1 or 2 risk factors), 63% of patients, with a 1-year OS of 63.7%; poor (>2 risk factors), 16% of patients, with a 1-year OS of 25.1% (Figure 3). Harrel's C statistic for OS of LIPS-4 in the training and validation cohorts was 0.72 (95% CI 0.63-0.79, P < 0.0001) and 0.64 (95% CI 0.59-0.68, P < 0.0001), respectively.

Discussion

There is currently clinical uncertainty about whether patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% aNSCLC should be treated with immunotherapy alone or in combination, either with chemotherapy, different ICIs or both. Two network meta-analyses showed that in this disease setting the addition of immunotherapy to chemotherapy could be superior to the immunotherapy alone in terms of objective response rate and progression-free survival, while a nonsignificant trend towards improved OS was observed.23,24 An ongoing clinical trial, the randomised phase III INSIGNA study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03793179), is comparing these approaches, without, however, formally looking at prognostic and predictive factors. This means that if combined approaches are found to be superior to immunotherapy alone, they could be indiscriminately administered to all patients, leading to potentially unnecessary treatment escalation as well as clinical and financial toxicity in several patients. This could also dilute the benefit of the combined approach in groups that deserve this treatment.

We validated baseline NLR with a cut-off of 4 as independent prognostic factor for patients with aNSCLC and PD-L1 ≥ 50% by different IHC assays treated with first-line immunotherapy with pembrolizumab. NLR < 4 identified approximately half of patients (53%) with an expected 1-year OS of 76.6%, which is in between that observed in the whole series for patients with a CR/PR (90.6%) and SD (71.5%) to the ICI. The validation of NLR as a prognostic biomarker confirms the importance of tumour inflammation and microenvironment.25 By contrast, despite the established predictive value of PD-L1 ≥ 50% by the 22C3 Dako pharmDx IHC assay,2,15 a threshold of PD-L1 expression level over 50% of tumour cells, besides the LDH, could not be validated as prognostic factors in this study. Although in this study the level of PD-L1 expression over 50% and the LDH value were missing in a relevant proportion of patients, particularly in the training cohort, as discussed below regarding the study limitations, this evidence jeopardises the previous attempts11,12 to combine these parameters in prognostic indexes or models to refine prognostic estimates. Patients with low NLR and PD-L1 ≥ 80% or normal LDH did not show a better outcome than those with low NLR alone, though the number of patients was roughly halved by the addition of these factors (21% for PD-L1 and 25% for the LDH). However, risk models combining NLR with PD-L1 or LDH were able to identify half of the patients (50% and 49%, respectively) with intermediate prognosis (1-year OS of 63.3% and 62.0%, respectively). This combined model also allowed the distinction of about a quarter of the patients with a poor prognosis, similar to that observed in those with NLR ≥ 4. Furthermore, we validated a risk model based on three validated clinical and laboratory independent prognostic factors, whose addition allowed an accurate prognostic stratification. The LIPS-3 included a baseline PS of 2, the use of pretreatment steroids and a baseline NLR ≥ 4. We explored a further risk model adding LDH to the LIPS-3, namely the LIPS-4. Compared with the LIPS-3 model, the LIPS-4 model almost halved the favourable risk group of patients (from 41% to 21%) in exchange for a modest improvement in the expected 1-year OS (from 78.2% to 81.3%). By contrast, LIPS-4 identified three times more (from 5% to 16%) poor prognosis patients than the LIPS-3, with 1-year OS of 25.1% as compared with 10.7% by the LIPS-3. A possible limitation of the LIPS-4 is the fact that baseline LDH ≥ 252 U/l was not validated, nor routinely performed in all centres and was missing in 27% of our patients.

An important difference between our work and other reports is that the cut-offs we used for NLR, PD-L1 and LDH were ROC based and quantitative. We also validated the cut-off for NLR in aNSCLC patients for the first time. Different cut-offs for NLR were reported in the literature. A cut-off of 5 was used in patients with NSCLC17 and validated in those with metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab,26 whereas a cut-off of 3 was included in The Lung Immune-Prognostic Index (LIPI) score for NSCLC patients,11 based on a larger and updated series of patients with metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab.27 No current validated cut-off is available for LDH. In our previous study on 132 patients with aNSCLC treated with first-line pembrolizumab, we observed a similar ROC-based LDH cut-off value of 268.5 U/l.12 The upper limit of normal value for each centre was used for the LIPI score, in which the median LDH value for all patients was 248.5 U/l.11 The prognostic value of LDH has also been confirmed for metastatic melanoma treated with immunotherapy with a value of at least 2.5 times the upper limit of normal28 or ≥480 U/l.29 Regarding the PD-L1 tumour cells expression level, we had already reported the same ROC-based cut-off of ≥80%.12 Furthermore, in a series of 187 NSCLC patients treated with first-line pembrolizumab, a higher threshold of ≥90% was correlated with better outcomes.16

Limitations of this study are the retrospective analysis of data from hospital records and the lack of a control cohort. Regarding the former, the accurate OS stratification by disease response (see Supplementary Figure S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100078) may be considered as proof of the quality of data input. Furthermore, it is worth noting that prognostic classifications and their validation (in most of the tumour types) very rarely came from prospective data. The latter does not allow us to discriminate between the prognostic and predictive values of the factors we investigated. However, a proper control cohort to explore the predictive value of NLR, PD-L1 expression, LDH and the LIPS in this specific setting would need to comprise patients treated with a combination of chemotherapy and ICI. This is currently unlikely in clinical practice for patients with NSCLC and PD-L1 ≥ 50%, specifically due to the lack of prognostic and predictive factors to make therapeutic choices in this setting. Intriguingly, beyond the first-line treatment, the LIPI score, or a high NLR combined with high LDH, did not predict worse outcomes from chemotherapy.11 Another limitation of the study concerns the rate of PD-L1 level expression and LDH missing data, particularly in the training (28% and 40%, respectively) rather than the validation cohort (32% and 23%, respectively). Besides, the sample size of the training cohort was calculated only based on the predicted difference in OS by the NLR. Although missing data on PD-L1 expression level and LDH reflect the large real-world evidence dataset and clinical practice, this could have led in the training cohort to miss a significant prognostic value of either of them or, consequently, of their combinations with NLR. Nevertheless, in the training cohort, we observed a significant prognostic value by either the PD-L1 expression levels and LDH; however, both were not confirmed in the large validation cohort.

Conscious of these limitations, we nonetheless believe LIPS-3 may represent an easy-to-assess, worldwide routinely available and inexpensive prognostic tool which could add relevant prognostic information to current decision-making algorithms and be tested in trial group comparisons for the first-line treatment of patients with aNSCLC and PD-L1 ≥ 50%. For instance, for patients with a favourable LIPS-3 score, a combined treatment with ICIs should prove its superiority to ICI monotherapy before being adopted in clinical practice; while the identification of patients at intermediate or poor risk by the LIPS-3 score could represent helpful information besides other clinical factors if an ICI combination approach is considered, no recommendation could be given until a formal comparison between ICI combination treatments and monotherapy is performed. Furthermore, patients with poor risk by the LIPS-3 score are unlikely to benefit from ICI alone and should be prioritised for investigational treatments or combinations (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

LIPS-3 adjuvant prognostic tool for the first-line treatment of patients with aNSCLC and PD-L1 ≥ 50%.

The LIPS-3 consists of the following three validated and independent prognostic factors: ECOG PS ≥ 2, use of pretreatment steroids and NLR ≥ 4. The OS curve refers to all patients according to the LIPS-3 score and corresponds to Figure 3C. For further details see Figure 3 legend.

aNSCLC, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ICIs, immune-checkpoint inhibitors; LIPS, Lung Immuno-oncology Prognostic Score; NLR, neutrophils-to-lymphocytes ratio; OS, overall survival.

In conclusion, we advocate the use of LIPS-3 as an accurate prognostic estimate of patients with aNSCLC with PD-L1 ≥ 50% receiving first-line immunotherapy. It is also a helpful tool to stratify these patients according to their outcomes, thus providing additional key elements to the treatment decision making in daily clinical practice and for randomised trials subgroup comparisons on ICIs and their combination strategies.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to the ‘Consorzio Interuniversitario Nazionale per la Bio-Oncologia’ for their support in this study.

Funding

None declared.

Disclosure

AC received speaker fees and grant consultancies from AstraZeneca, MSD, BMS, Roche, Novartis and Astellas. EB received speaker and travel fees from MSD, Astra-Zeneca, Pfizer, Helsinn, Eli-Lilly, BMS, Novartis and Roche; received grant consultancies from Roche and Pfizer. MT received speaker fees and grant consultancies from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Eli-Lilly, BMS, Novartis, Roche, MSD, Boehringer Ingelheim, Otsuka, Takeda and Pierre Fabre. AM received speaker fees from Astra, Roche, BMS, MSD, Boehringer, Pfizer and Takeda. FM received grant consultancies from MSD and Takeda. RG received speaker fees and grant consultancies from AstraZeneca and Roche. AF received grant consultancies from Roche, Pfizer, Astellas and BMS. AA received grant consultancies from Takeda, MSD, BMJ, AstraZeneca, Roche and Pfizer. RC received speaker fees from BMS, MSD, Takeda, Pfizer, Roche and AstraZeneca. CG received speaker fees/grant consultancies from Astra Zeneca, BMS and Boehringer-Ingelheim. GLB personal fees from Janssen Cilag, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca and Roche, outside the submitted work. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing

The datasets used during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Banna G.L., Passiglia F., Colonese F. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer: a tool to improve patients' selection. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;129:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reck M., Rodriguez-Abreu D., Robinson A.G. Updated analysis of KEYNOTE-024: pembrolizumab versus platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 tumor proportion score of 50% or greater. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(7):537–546. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Addeo A., Banna G.L., Metro G. Chemotherapy in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors for the first-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and literature-based meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2019;9:264. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hellmann M.D., Paz-Ares L., Bernabe Caro R. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2020–2031. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paz-Ares L., Ciuleanu T.E., Cobo M. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:198–211. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Addeo A., Banna G.L., Weiss G.J. Tumor mutation burden-from hopes to doubts. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):934–935. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banna G.L., Olivier T., Rundo F. The promise of digital biopsy for the prediction of tumor molecular features and clinical outcomes associated with immunotherapy. Front Med. 2019;6:172. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavakkoli M., Wilkins C.R., Mones J.V. A novel paradigm between leukocytosis, G-CSF secretion, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:295. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaul M.E., Fridlender Z.G. Tumour-associated neutrophils in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(10):601–620. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mei Z., Shi L., Wang B. Prognostic role of pretreatment blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in advanced cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 66 cohort studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;58:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mezquita L., Auclin E., Ferrara R. Association of the lung immune prognostic index with immune checkpoint inhibitor outcomes in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):351–357. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banna G.L., Signorelli D., Metro G. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in combination with PD-L1 or lactate dehydrogenase as biomarkers for high PD-L1 non-small cell lung cancer treated with first-line pembrolizumab. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2020;9:1533–1542. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-19-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banna G.L., Di Quattro R., Malatino L. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and lactate dehydrogenase as biomarkers for urothelial cancer treated with immunotherapy. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22:2130–2135. doi: 10.1007/s12094-020-02337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takada K., Toyokawa G., Shoji F. The significance of the PD-L1 expression in non-small-cell lung cancer: trenchant double swords as predictive and prognostic markers. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19(2):120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mok T.S.K., Wu Y.L., Kudaba I. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1819–1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguilar E.J., Ricciuti B., Gainor J.F. Outcomes to first-line pembrolizumab in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and very high PD-L1 expression. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(10):1653–1659. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagley S.J., Kothari S., Aggarwal C. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a marker of outcomes in nivolumab-treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2017;106:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cortellini A., Tiseo M., Banna G.L. Clinicopathologic correlates of first-line pembrolizumab effectiveness in patients with advanced NSCLC and a PD-L1 expression of >/= 50% Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69:2209–2221. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02613-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cortellini A., Friedlaender A., Banna G.L. Immune-related adverse events of pembrolizumab in a large real-world cohort of patients with NSCLC with a PD-L1 expression >/= 50% and their relationship with clinical outcomes. Clin Lung Cancer. 2020;21:498–508.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McShane L.M., Altman D.G., Sauerbrei W. REporting recommendations for tumour MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK) Br J Cancer. 2005;93(4):387–391. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bleeker S.E., Moll H.A., Steyerberg E.W. External validation is necessary in prediction research: a clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(9):826–832. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Y., Lin Z., Zhang X. First-line treatment for patients with advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma and high PD-L1 expression: pembrolizumab or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy. J Immun Cancer. 2019;7(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim R., Keam B., Hahn S. First-line pembrolizumab versus pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20(5):331–338.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuca G., Galli G., Poggi M. Modulation of peripheral blood immune cells by early use of steroids and its association with clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. ESMO Open. 2019;4(1):e000457. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrucci P.F., Gandini S., Battaglia A. Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with outcome of ipilimumab-treated metastatic melanoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(12):1904–1910. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrucci P.F., Ascierto P.A., Pigozzo J. Baseline neutrophils and derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: prognostic relevance in metastatic melanoma patients receiving ipilimumab. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(4):732–738. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weide B., Martens A., Hassel J.C. Baseline biomarkers for outcome of melanoma patients treated with pembrolizumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(22):5487–5496. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simeone E., Gentilcore G., Giannarelli D. Immunological and biological changes during ipilimumab treatment and their potential correlation with clinical response and survival in patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(7):675–683. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1545-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.