Abstract

Modified titanium dioxide (m-TiO2NPs) is a novel photocatalytic nanomaterial. Its level of toxicity was evaluated to be used in photodynamic treatment for cervical cancer. In the toxicity studies (Irwin test, acute and repeated doses (10 days)), female albino Swiss Webster (CFW) mice, 28 days old were used; the m-TiO2NPs was administered in single 300, 600 and 5,000 mg/kg of body weight (b.w) doses injected in the peritoneal zone. No adverse events or mortality were produced. Daily intraperitoneal doses of 300 and 600 mg/kg b.w every 24 h for 10 days did not produce adverse effects or mortality. There were no abnormal clinical signs or behavioral changes (neurological or physiological) in any of the mice. All organs exhibited normal architecture, and histological studies determined that m-TiO2NPs does not produce changes in the cells or tissues. Based on the test results, it is concluded that the m-TiO2NPs has not a toxic effect in doses equal to or less than 5,000 mg/kg b.w.

Keywords: Modified titanium dioxide, Acute toxicity, Repeated dose toxicity, Murine biomodels

Modified titanium dioxide; Acute toxicity; Repeated dose toxicity; Murine biomodels.

1. Introduction

Toxicity studies of nanomaterials are important, and identifying damage to the lungs, heart, and other organs have received much attention [1, 2]. Toxic risk estimation is a complex process of balancing the risks and benefits of employing such substances [3, 4]. Experiments with biological models are the main sources for providing information on the toxicological properties and the kinetics of chemical substances. Methods in this research include the Irwin test and acute toxicity [5, 6] and repeated dose toxicity tests [7].

The Irwin test occupies a prominent place in the preliminary assessment of new drugs and their effects on the central nervous system (CNS) [8]. Its simple execution and the sufficient validity it provides make its practice very useful before continuing with more complex tests [9]. The development of this test is summarized in three major categories: behavioral studies, neurological studies and studies related to the autonomic nervous system (ANS) [9]. Irwin described his behavioral screening assay to be a complex process that required: 1) specialized training; 2) a common rating scale for each of the selected parameters (nominal, ordinal, interval or ratio scale); 3) each animal to serve as its own control using a schedule of pre-dose and post-dose observations of the same subjects [10, 11].

The acute toxicity test is understood as the ability of a substance to produce adverse effects after a single exposure [12]. These effects can vary from skin irritation to death [7, 13]. It is necessary to know the toxicity range of the substance, which implies taking into account two estimates [7]:

-

a)

A median letal dose (LD50) less than 25 mg/kg is so strongly toxic that it is not worth determining with greater accuracy [7]; and

-

b)

An LD50 greater than 5,000 mg/kg represents such low acute toxicity that it is also not necessary to determine it more accurately [7]..

As a consequence, the substances are classified into four categories according to their approximate LD50 values: highly toxic, toxic, noxious and unclassified [7].

The limit test is applied when low toxicity is assumed, and it is carried out by applying doses of 2,000 or 5,000 mg/kg to an animal [7]. If it dies, the complete essay is performed, but otherwise, the low toxicity is confirmed using 4 animals sequentially [7].

The main objectives of repeated dose studies are to evaluate the long-term effects, and to determine the dose at which no adverse effect is observed [14, 15]. The target organs are identified, and the possible reversibility of the effects is determined, as well as detecting whether the effects are cumulative or delayed [7]. The administration of the product should be daily since it has been observed that if it is performed 5 days a week and not 7 days a week, the 48-h rest period can allow recovery from the toxic effects [7].

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is an amphoteric and chemically stable metal oxide semiconductor [16, 17, 18] with great potential. TiO2 has an adequate band gap value (~3 eV) [18]. It has four crystalline phases: rutile (tetragonal structure), anatase (octahedral structure), which has the highest photocatalytic activity, brookite (orthorhombic structure) and α-PbO2 type (high pressure amorphous) [16, 17, 18]. TiO2 nanoparticles (NPs) are the most produced nanomaterials, with a worldwide production of 10,000 tons, and the second most used nanomaterial in consumer products [19]. With the extensive application of TiO2NPs in the industry [20, 21, 22], there is a growing debate about the possible risk associated with exposure to it [23, 24, 25].

They are also used for medical purposes, for example as photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy [26], in tissue engineering, and therapeutic drug development [27]. TiO2NPs are used in the treatment of various types of cancer to overcome the limits of conventional treatments due to its possible cytotoxicity when exposed to UV light (heterogeneous photocatalysis) [28]; it can also induce chemical reactions with UV radiation [29]. In recent years, TiO2 based drug delivery systems have demonstrated the ability to decrease the risk of tumorigenesis and improve cancer therapy [27]. TiO2-NPs cause decreased cell proliferation, adhesion, and increased apoptosis in breast cancer cells [30]. Studies of TiO2 nanosquares (TNS) and TiO2 nanotubes (TNT) (developed and evaluated for anti-cancer activity In vitro and In vivo) suggest that these materials inhibited proliferation of breast cancer MDAMB 231 cells In vitro, in a shape-dependent manner [31]. In addition, TiO2NPS inhibited the migration and colony formation of breast cancer MDAMB231 cells. TiO2NPS induced the up-regulation of tumor suppressor genes p53, MDA7, TRAIL and transcription factor STAT3 [31].TiO2NPS for microwave (Microdynamic Therapy) exhibited higher cytotoxicity on cancer cells (osteosarcoma UMR-106 cells) than on normal cells (mouse fibroblast L929 cells) [32].

Given the increasing use of TiO2NPS in everyday products and health concerns regarding their use, we modified and examined their potential cytotoxicity using cervical cancer cell lines. The modified Titanium dioxide nanoparticle (m-TiO2NPs) comprising functionalized multilayer carbon nanotubes (FMWCNTs) and TiO2 anatase phase was synthesized by the Physicochemistry of Bio and nanomaterials Research Group using a sol-gel pathway [33]. These novel m-TiO2NPs are more cytotoxic to tumor cells (HeLa CCL-2 cell line) when combined with UV light (99 % of cytotoxicity) than on normal cells (CHO –K1 cell line) also exposed to UV light, both during 40 min [33]. The difference between the use of TiO2NPS in the treatment of cancer with conventional therapy is the selectivity of these nanoparticles for cancer cells [30, 33].

The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate the toxicity of a novel photocatalytic m-TiO2NPs by Irwin test, acute and repeated dose toxicity tests. The results of the Irwin test were used to determine potential toxicity and to select doses for specific therapeutic activity [34]. The Irwin test can help to determine the dose range to be tested in other safe tests [7]. Acute toxicity describes the adverse effects of a substance that result from a single dose while chronic toxicity describes the adverse health effects from repeated exposures [7].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

-

1.

Modified Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (m-TiO2NPs): A fully characterized pure anatase TiO2NPs with functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotube (FMWCNT) used in the present study were synthesized by the Physicochemistry of Bio and nanomaterials Research Group using a sol-gel pathway (detailed description of the synthesis of m-TiO2NPs was published in the patent number WO2016055869A1) (Figure 1) [33]. The characterizations of the m-TiO2NPs were as follows: pure anatase nanopowder and white odorless fine powder with a particle size of <100 nm (Figure 2) and purity of ≥99 %. Initially, the alternative photodynamic therapy with m-TiO2NPs was studied being their selectivity for cancer cell lines the principal finding [33].

Figure 1.

m-TiO2 NPs, pure anatase TiO2NPs with functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotube (FMWCNT).

Figure 2.

-

2.Normal saline: 0.9% NaCl solution from a local pharmacy [35].

2.1.1. Experimental animals

Thirty-six (36) female albino Swiss Webster (CFW) mice, weighing 19 ± 3 g, 28 days old, were obtained and maintained at the Animal House of the Faculty of Medicine, Universidad del Valle, Colombia (Table 1). The acclimatization period was 2 weeks. Mice were housed in filter-top plastic cages in a controlled temperature (19–23 °C) and humidity (60–90%) and an artificially illuminated (12:12 h light:dark cycle) room, free from any source of chemical contamination. They had free access to the pelleted feed and the drinking water supply of the site. Noises, vibrations, and smells were minimized, and gloves and tweezers were used to change the beds of the cages. During the experiment, the animals were not paralyzed with chemical agents, placed under physical restrictions for greater than 12 h, nor nutritional distress for more than 24 h.

Table 1.

Experimental design of toxicology study.

| Group∗ | Mice number | Dose/day m-TiO2NPs (mg/kg) | Doses number |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3 | 300 | 1 |

| B | 3 | 300 | 10 |

| C | 3 | 600 | 1 |

| D | 6 | 600 | 10 |

| E | 6 | 5,000 | 1 |

Control group: 3 female mice of the same age were used as control for each experimental group.

The experiment was carried out in compliance with the guidelines of Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, and National Research Council (2010), and the Universidad del Valle institutional guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals. The project was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Universidad del Valle, Colombia.

2.1.2. Experimental design

The mice were randomly assigned to four groups (Table 1). They were caged separately. Saline was used as a vehicle to suspend m-TiO2NPs and the suspension was sonicated [35]for 15 min before the treatment. Animals were weighed before the dose administration.

Control groups (untreated control groups): kept without treatment and used as control for each experimental group to measure the parameters to be compared with each experimental group.

Group A: Each mouse was treated with m-TiO2NPs at a dose of 300 mg/kg b.w suspended in 0.1 ml of normal saline. The suspension was given a single dose by intraperitoneal (i.p) injection. Mice were sacrificed 10 days after the single exposure. The dose level for m-TiO2NPs was based on previously published reports of Jiaying Xu, et al [6].

Group B: Each mouse was treated with m-TiO2NPs at a dose of 300 mg/kg b.w/day suspended in 0.1 ml of normal saline. The suspension was given once daily by intraperitoneal (i.p) injection for 10 days. Mice were sacrificed 10 days after the last exposure.

Group C: Each mouse was treated with m-TiO2NPs at a dose of 600 mg/kg b.w suspended in 0.2 ml of normal saline. The suspension was given a single dose by i.p injection. Mice were sacrificed 10 days after the single exposure.

Group D: Each mouse was treated with m-TiO2NPs at a dose of 600 mg/kg b.w/day suspended in 0.2 ml of normal saline. The suspension was given once daily by i.p injection for 10 days. Mice were sacrificed 10 days after the last exposure.

Group E: Each mouse was treated with m-TiO2NPs at a dose of 5,000 mg/kg b.w suspended in 0.6 ml of normal saline. The suspension was given a single dose by i.p injection. Mice were sacrificed 10 days after the single exposure.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Irwin test study

Behavior, physiological and neurological response of Autonomic Nervous System of mice inoculated with m-TiO2NPs were studied.

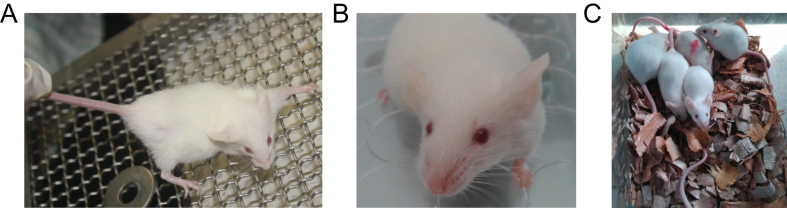

The modified Irwin test and the Irwin test were performed during this research [36]. The modified Irwin test consisted on the observation of the mice pre- and post-applications by injecting the m-TiO2NPs, at times 0, 15, and 30 min; the Irwin test consisted of follow-up observations at 1, 4 and 24 h [11, 37]. During this time, observation tests were performed with and without human presence (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Irwin test results by comparison with control mice: (A) strength test on a grid, (B) color of skin, eyes, and ears, as well as eye shape in a normal test mouse, and (C) normal group behavior.

We evaluated Group D and E with the modified Irwin test and the Irwin test, observing the following: if the animal was awake or asleep; if it was restless, showed fear, aggressiveness or indifference with regards to the experimenter; and if it was silent or made noises. The position of the body, locomotor activity (movements of grooming), abnormal behavior (tremors, shaking or convulsions); changes in the skin, fur, mucous membrane, eyes, respiration, behavior patterns were also observed [9]. Each parameter was scored on a 0 to 3 scale, with 0 representing the response in a normal group animal and 3 representing a maximally impaired animals [11, 38] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Irwin test scoring method.

| Scale | Term | Impaired animal/total animals (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Normal | 0/6 |

| 1 | Slightly impaired | 1-2/6 |

| 2 | Moderately impaired | 3-4/6 |

| 3 | Maximally impaired | 5-6/6 |

2.2.2. Acute and repeated dose toxicity study

We used the acute toxic class method (ATC method) [39]. The ATC method is a sequential testing procedure using only three animals of one sex per step at any of the defined dose levels. Depending on the mortality rate three but never more than six animals are used per dose level [39, 40].

Animals are dosed one group at a time. If all the animals survived, the dose for the next group was increased; if they died, the dose was decreased. Every group of animals was observed for the first 24 h and daily for a total of 10 days before dosing the next group of animals. Attention was given to toxicity signs including mortality [41]. The animals that survived were monitored for delayed death for a total of 10 days. The rate of mortality in each group was noted. At the end of the period of the study, dead animals would be counted for the calculation of LD50. All mice were sacrificed 10 days after the last exposure.

The experiment started with the acute toxicity on Group A, at a dose of 300 mg/kg b.w that is twice as higher than the human dose [5] (Table 1). Then, after the results were obtained, the experiment was carried on Group B, at the same dose of 300 mg/kg b.w/day during 10 days, to study the repeated dose toxicity.

After obtaining the results of Group A and B, the dose was duplicated to carry the acute and repeated dose toxicity study on Groups C and D. The increase of the dose finally got to the maximum of 5000 mg/kg b.w (Group E) equivalent to 35 times higher than the human dose [5].

The Karber's method was used for the determination of LD50 as per Eq. (1), [5].

| LD50 = LD100 −∑ (a x b)/n | Equation 1 |

n = total number of animal in a group.

a = the difference between two successive doses of administered extract/substance.

b = the average number of dead animals in two successive doses.

LD100 = Lethal dose causing the 100% death of all test animals.

The Repeto's toxicity range [7] and Hodge and Sterner toxicity scale (Table 3) were used for the evaluation of toxicity with the help of LD50.

Table 3.

Hodge and Sterner toxicity scale [5].

| No. | Term | LD50 mice (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Extremely Toxic | Less than 1 |

| 2 | Highly Toxic | 1–50 |

| 3 | Moderately Toxic | 50–500 |

| 4 | Slightly Toxic | 500–5000 |

| 5 | Practically Non-Toxic | 5000 - 15,000 |

2.2.3. Dissection

Ten days after the last dose, all mice in both the acute and the repeated dose toxicity tests were dissected for histological studies of the organs. The following organs were extracted: brain, eyes, heart, lungs, skin, peritoneum, stomach, small and large intestines, liver and kidney, which were stored in bottles with 10% formaldehyde. Anesthesia and euthanasia were carried out with isoflurane under protocols already established at the Animal Ethics Committee of Universidad del Valle, Colombia.

2.2.4. Histopathological study

The extracted organs were fixed with 4% formalin buffer, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, sectioned to a thickness of 4μm, mounted on glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) [42]. Images were observed under a light microscope (Olympus Microscope BX41).

The histopathologic scoring method applied to tissues in each individual animal of the Groups D and E as control for each group was described in Table 4 [43,44]. Parameters of the histological study consisted of the degree of inflammation (leukocyte or neutrophil infiltrate, polymorphonuclear cells, macrophages, plasma cells, eosinophils lymphocyte) m-TiO2NPs in organs, and the abnormality of cells and tissues (cell necrosis). No need for a positive control in this experiment according to a fully trained Veterinarian pathologist that examined all histological samples [43, 44].

Table 4.

Histopathologic scoring method.

| m-TiO2NPs in organs | |

| 0 | Absent |

| 1 | 1-2 NPs/HPF∗ |

| 2 | 3-4 NPs/HPF |

| 3 | ≥4 NPs/HPF |

| Cell necrosis | |

| 0 | Absent |

| 1 | Focal occurrence of 1–5 necrotic cells/HPF |

| 2 | Diffuse occurrence of 1–5 necrotic cells/HPF |

| 3 | Same as 2 + focal occurrence of 1–5 necrotic cells/HPF |

| 4 | Diffuse occurrence of ≥6 necrotic cells/HPF |

| Leukocyte or neutrophil infiltrate | |

| 0 | Absent |

| 1 | 1–5 infiltrated cell/HPF |

| 2 | ≥6 infiltrated cell/HPF |

| Polymorphonuclear cells | |

| 0 | Absent |

| 1 | 1–5 infiltrated cell/HPF |

| 2 | ≥6 infiltrated cell/HPF |

| Macrophages, | |

| 0 | Absent |

| 1 | 1–5 infiltrated cell/HPF |

| 2 | ≥6 infiltrated cell/HPF |

| Plasma cells | |

| 0 | Absent |

| 1 | 1–5 infiltrated cell/HPF |

| 2 | ≥6 infiltrated cell/HPF |

| Eosinophils lymphocyte | |

| 0 | Absent |

| 1 | 1–5 infiltrated cell/HPF |

| 2 | ≥6 infiltrated cell/HPF |

3. Results

3.1. Toxicology study: Irwin test

The administration of the doses of m-TiO2NPs at concentrations of 600 and 5,000 mg/kg b.w via the i.p route to the mouse, resulted in no observable changes to motor activity, coloration of the ears, grooming, or aggressiveness. Additionally, there were no tremors; catalepsy, or tonic, clonic or tonic-clonic seizures (Table 5 and Table 6). There was also no decreased in reflexes or strength (Figure 3, A), nor central muscle relaxation due to a decrease in muscle tone (Figure 3, B). There were no presence of piloerection or sign of Straub tail (Figure 3, C), no paralysis or poor motor coordination and no changes in grooming.

Table 5.

Irwin test results of the Group D.

| Treatment |

GROUP D |

GROUP CONTROL D |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation Time | 0-15′ | 15′ | 30′ | 1h | 4h | 24h | 0-15′ | 15′ | 30′ | 1h | 4h | 24h | |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Exitation | Convulsions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tremor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Straub tail | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased activity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Jumping | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased fear/startle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased reactivity to touch | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased abdominal muscle tone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Aggression | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Steretypy | Head-twitches | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stereotypies (Head movements) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Stereotypies (Chewing) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Stereotypies (Sniffing) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Scratching | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Motor | Catalepsy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Akinesia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Abnormal gait (rolling) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Abnormal gait (tip-toe) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Motor incoordination | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Loss of traction | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Loss of grasping | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sedation | Decreased activity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased fear/startle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Decreased reactivity to touch | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Decreased abdominal muscle tone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pain | Writhing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Analgesia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Autonomic | Ptosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Exophthalmia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Myosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mydriasis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pilorection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Defecation/diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Salivation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lacrimation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

(0) 0/6; (1) 1–2/6; (2) 3–4/6; (3) 5–6/6

Table 6.

Irwin test results of the Group E.

| Treatment |

GROUP E |

GROUP CONTROL E |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation Time | 0-15′ | 15′ | 30′ | 1h | 4h | 24h | 0-15′ | 15′ | 30′ | 1h | 4h | 24h | |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Exitation | Convulsions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tremor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Straub tail | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased activity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Jumping | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased fear/startle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased reactivity to touch | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased abdominal muscle tone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Aggression | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Steretypy | Head-twitches | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stereotypies (Head movements) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Stereotypies (Chewing) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Stereotypies (Sniffing) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Scratching | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Motor | Catalepsy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Akinesia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Abnormal gait (rolling) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Abnormal gait (tip-toe) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Motor incoordination | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Loss of traction | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Loss of grasping | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sedation | Decreased activity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased fear/startle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Decreased reactivity to touch | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Decreased abdominal muscle tone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pain | Writhing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Analgesia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Autonomic | Ptosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Exophthalmia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Myosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mydriasis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pilorection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Defecation/diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Salivation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lacrimation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

(0) 0/6; (1) 1–2/6; (2) 3–4/6; (3) 5–6/6

3.2. Toxicology study: acute toxicity and repeated dose tests

The results of acute toxicity tests and repeated dose tests (10 days) show that all mice survived single doses of m-TiO2NPs at all acute administered concentrations (300–5,000 mg/kg b.w) as well as repeated doses of 300 and 600 mg/kg b.w every 24 h for 10 days (Table 7).

Table 7.

Toxicological study of different doses of m-TiO2NPs administered i.p in mice.

| Group | Dose/day (mg/kg) | Doses number | Mortality (X/n) n = experimental mice | Mortality (X/m) m = control mice | Dead (%) | Symptoms None |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 300 | 1 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0 | None |

| B | 300 | 10 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0 | None |

| C | 600 | 1 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0 | None |

| D | 600 | 10 | 0/6 | 0/3 | 0 | None |

| E | 5,000 | 1 | 0/6 | 0/3 | 0 | None |

LD50 Value: As per observations and calculations (Karber, 1931), the LD50 value of m-TiO2NPs after i.p administration was found to be more than 5,000 mg/kg b.w.

According to Repeto's toxicity range and Hodge and Sterner (2005) toxicity scale, m-TiO2NPs is said to be in non-toxic drug category.

3.3. Dissection

Figure 4 shows dissection of mouse inoculated with m-TiO2NPs at 5,000 mg/kg b.w and the control mice. The arrows show the m-TiO2NPs (white cumulus) in the i.p area in contrast of control mice (Figure 4, A).

Figure 4.

Dissection of mice exposed to m-TiO2NPs: the arrows show the m-TiO2NPs: (A) dissection of mouse inoculated with m-TiO2NPs at 5,000 mg/kg b.w in the i.p area, (B) histological tissue section in the peritoneal area of the inoculated mouse (20X), (C) dissection of control mouse, (D) histological tissue section in the peritoneal area of control mouse (20X).

During the dissection of all experimental groups of mice, we observed the m-TiO2NPs accumulated in the area of the injection and in part of the large and small intestines (Figure 4, A). However, the histological section shows the peritoneal area with m-TiO2NPs, with normal cells and no evidence of acute or chronic inflammation (Figure 4, B). All organs exhibited normal architecture similar to the control group.

3.4. Histological studies

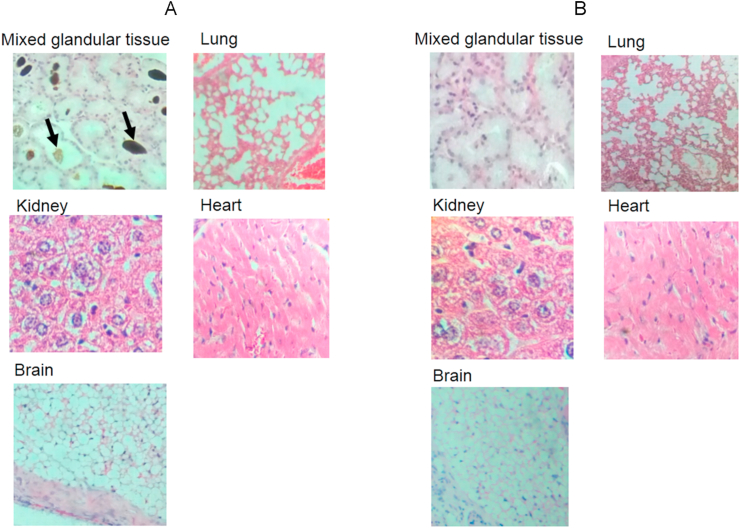

The images shown in Figure 5 are of organs of mice exposed to m-TiO2NPs, from both acute and repeated dose toxicity tests (Groups D and E as control for each group). There is evidence of the presence of the nanomaterial in mixed glandular (salivary) tissue (Figure 5, A) and in the peritoneal area of control mouse (Figure 4, B).

Figure 5.

Histological studies of tissues: (A) Mice exposed to m-TiO2NPs; mixed glandular tissue (salivary), the arrow show m-TiO2NPs precipitate (10X), lung (10X), kidney (10X), heart (20X), brain (20X). (B) Control mouse tissue; mixed glandular tissue (10X), lung (10X), kidney (10X), heart (20X), brain (20X).

Figure 6 shows results of histopathologic scoring m-TiO2NPs in tissues of organs such as the lung, brain, heart, kidney, liver, small and large intestines, skin, stomach and, peritoneum. The peritoneum scoring was the highest obtained and, m-TiO2NPs was absent in brain and skin.

Figure 6.

m-TiO2NPs in tissues of organs such as the lung, brain, heart, kidney, liver, small and large intestines, skin, stomach and, peritoneum. (A) Group E, acute dose toxicity test, (B) Group D, repeated dose toxicity tests.

Table 8 and Table 9 show the normal limits inflammation in group D (n = 6) and E (n = 6). Results of histopathologic scoring method show absent necrosis cells, leukocyte or neutrophil infiltrate, macrophages, plasma cells and, eosinophils lymphocyte. The polymorphonuclear cells had scoring 1 (1–5 infiltrated cell/HPF).

Table 8.

Average of histological scoring in tissues of organs such as the lung, brain, heart, kidney, liver, small and large intestines, skin, stomach and, peritoneum in each group.

| Cell in tissues | Group D (n = 6) | Control group D (n = 6) | Group E (n = 6). | Control group E (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell necrosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Leukocyte or neutrophil infiltrate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Polymorphonuclear cells | 0 | 0 | 0.2a | 0 |

| Macrophages | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Plasma cells | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eosinophils lymphocyte | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

This was found in the lung of one single mouse.

Table 9.

Presence of cellular inflammationa.

| Group | Normal | Inflammation | % inflammation |

|---|---|---|---|

| D | 5 | 1 | 16.6 |

| Control D | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| E | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Control E | 6 | 0 | 0 |

Sections of tissues from each animal in group D (n = 6) and E (n = 6) were examined and designated as within normal limits.

4. Discussion

The present study is the first report about m-TiO2NPs toxicity in mice. It is not toxic at the levels tested. The behavior of CWF mice biomodels in the presence of m-TiO2NPs was normal when compared to the control mice. The nanomaterial administered at doses of 300 mg/kg, 600 mg/kg and 5,000 mg/kg b.w does not cause alteration in the motor performance of the exposed animals, nor did it have any adrenergic effect. The nanomaterial had no significant cholinergic effect or laxative effect because diarrhea did not occur. The mice did present any seizures, which means that there is no excitatory effect at the Central Nervous System (CNS) level [45].Because there were no signs of decreased motor activity or reflexes, it can be suggested that there are no sedative or hypnotic effects. Similarly, Straub's sign (erection of the tail) [46] was not present, and thus, there was no analgesic effect of the opioid type.

The tests of acute and repeated dose toxicity with m-TiO2NPs at doses of and lower than 5,000 mg/kg b.w determined that it is not toxic. It is important to mention that 5,000 mg/kg b.w is the maximum dose recommended in toxicity studies in mice (35 times greater than human dose [5]), and more research at higher doses is not considered necessary [7]. Doses equal to or less than 5,000 mg/kg b.w. does not change the behavior or the neurological and physiological state of the mice.

No pathological effects were observed in the heart in TiO₂ NPs treated mice, which agrees with Jiaying Xu, et al [6]. Other organs like kidney and spleen did not show any significant change. Previously reported data revealed the toxic effect of different to ours TiO₂NPs at different doses such as 5,000 mg/kg b.w when administrated to mice via oral gavage [47]. Acute inflammatory responses in mice treated with 2.5, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/m3 TiO₂ NPs [48]. Myocardial toxicity [35] and pathological lesions of the liver, spleen, kidneys, and brain [49].

In the present study, our m-TiO2NPS compound was found to be safe up to 5,000 mg/kg intraperitoneal. The histopathology studies show no evidence of changes in the cells or tissues and that could indicate the presence of inflammatory cells such as polymorphonuclear cells, macrophages, plasma cells, and eosinophils lymphocytes or neutrophils. And the results showed that all animals survived at doses of and lower than 5,000 mg/kg b.w determining that it is not lethal or even toxic.

This present study is in agreement with Zhang et al in which the relationship between NPs toxicity and physicochemical properties is largely unknown [50]. For that reason, is important to know that m-TiO2NPS used in this work is a novel material [33] with different physicochemical properties that commercial TiO2 NPS and other types of TiO2 NPS.

5. Conclusion

All organs exhibited normal architecture. Organs like kidney, heart, and brain did not show any significant change. Histological studies determined that it accumulates in the injection area of the animal model, there being no changes in the cells or tissues. This work is the first report of the application of m-TiO2NPs nanomaterial In vivo tests and in the absence of UV light, demonstrating that m-TiO2NPs administered i.p in albino CFW mice does not have any toxic effect in doses equal to or less than 5,000 mg/kg b.w. The results of the present study allows us to conclude that m-TiO2NPs is safe and practically non-toxic when administered i.p.

In the future, the results of this research can be used continue testing it by administering it by different routes, and different animal species, with different sources of energies which could conclude by applying eventually to treat some form of human cancer.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Mónica Basante-Romo: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Jose Oscar Gutiérrez-M; Rubén Camargo- Amado: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Department of Science, Technology and Innovation COLCIENCIAS, Universidad del Valle (Cali-Colombia), and doctoral national program 528 of COLCIENCIAS.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank bacteriologist Jaime Muñoz for assisting with collecting the toxicity data, Rodrigo Zambrano D.V.M. and MSc. Veterinary pathologist Jaime Payán D.V.M for providing technical feedback throughout histological studies.

References

- 1.Arora S., Rajwade J.M., Paknikar K.M. Nanotoxicology and in vitro studies : the need of the hour. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012;258:151–165. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warheit D.B., Brown S.C. What is the impact of surface modifications and particle size on commercial titanium dioxide particle samples? – a review of in vivo pulmonary and oral toxicity studies – revised 11-6-2018. Toxicol. Lett. 2019;302:42–59. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruiz A.L.T.G., Taffarello D., Souza V.H.S., Carvalho J.E. Farmacologia e Toxicologia de Peumus boldus e Baccharis genistelloides. Rev. Bras Farmacogn. 2008;18:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorenzo Fernández P., Alfaro Ramos M.J., Lizasoain Hernández I., Leza Cerro J.C., Moro Sánchez M.Á., Portolés Pérez A. 2008. Velazquez; Farmacología Básica Y Clínica. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed M. Acute toxicity ( lethal dose 50 calculation ) of herbal drug somina in rats and mice. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2015;6:185–189. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu J., Shi H., Ruth M., Yu H., Lazar L., Zou B. Acute toxicity of intravenously administered titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mice. PloS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Repeto M., Repetto Kuhn G. fourth ed. 2009. Toxicología Fundamental. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonck C., Pietras M.R., Bialecki R.A., Easter A. CNS adverse effects: from functional observation battery/Irwin tests to electrophysiology. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2015;229:83–113. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-46943-9_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roux S., Sablé E., Porsolt R.D. Primary observation (Irwin) test in rodents for assessing acute toxicity of a test agent and its effects on behavior and physiological function. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2005 doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph1010s27. Chapter 10:Unit 10.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redfern W.S., Dymond A., Strang I., Storey S., Grant C., Marks L. The functional observational battery and modified Irwin test as global neurobehavioral assessments in the rat: pharmacological validation data and a comparison of methods. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2019;98:106591. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2019.106591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roux S., Sablé E., Porsolt R.D. Primary observation (Irwin) test in rodents for assessing acute toxicity of a test agent and its effects on behavior and physiological function. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2004 doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph1010s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moorthy M., Joon J., Palanisamy U.D. Heliyon Acute oral toxicity of the ellagitannin geraniin and a geraniin-enriched extract from Nephelium lappaceum L rind in Sprague Dawley rats. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saif M.W. Advancements in the management of pancreatic cancer: 2013. JOP. 2013;14:112–118. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H., Ma L., Liu J., Zhao J., Yan J., Hong F. Toxicity of nano-anatase TiO2 to mice: liver injury, oxidative stress. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2010;92:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park E.-J., Bae E., Yi J., Kim Y., Choi K., Lee S.H. Repeated-dose toxicity and inflammatory responses in mice by oral administration of silver nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010;30:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luttrell T., Halpegamage S., Tao J., Kramer A., Sutter E., Batzill M. Why is anatase a better photocatalyst than rutile? - model studies on epitaxial TiO2 films. Sci. Rep. 2015;4:4043. doi: 10.1038/srep04043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scanlon D.O., Dunnill C.W., Buckeridge J., Shevlin S.A., Logsdail A.J., Woodley S.M. Band alignment of rutile and anatase TiO2. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nmat3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dette C., Pérez-Osorio M.A., Kley C.S., Punke P., Patrick C.E., Jacobson P. TiO2 anatase with a bandgap in the visible region. Nano Lett. 2014;14:6533–6538. doi: 10.1021/nl503131s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piccinno F., Gottschalk F., Seeger S., Nowack B. Industrial production quantities and uses of ten engineered nanomaterials in Europe and the world. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nickheslat A., Amin M.M., Izanloo H., Fatehizadeh A., Mousavi S.M. Phenol photocatalytic degradation by advanced oxidation process under ultraviolet radiation using titanium dioxide. J. Environ. Publ. Health. 2013;2013:815310. doi: 10.1155/2013/815310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weir A., Westerhoff P., Fabricius L., Hristovski K., von Goetz N. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles in food and personal care products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:2242–2250. doi: 10.1021/es204168d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiong L.-B., Li J.-L., Yang B., Yu Y. Ti3+ in the surface of titanium dioxide: generation, properties and photocatalytic application. J. Nanomater. 2012;2012:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bermudez E., Mangum J.B., Wong B.A., Asgharian B., Hext P.M., Warheit D.B. Pulmonary responses of mice, rats, and hamsters to subchronic inhalation of ultrafine titanium dioxide particles. Toxicol. Sci. 2004;77:347–357. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen T., Yan J., Li Y. Genotoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Yao Wu Shi Pin Fen Xi = J Food Drug Anal. 2014;22:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin Z., Ma L., Z-G X., Zhang H., Lin B. A comparative study of lung toxicity in rats induced by three types of nanomaterials. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013;8:521. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-8-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szaciłowski K., Macyk W., Drzewiecka-Matuszek A., Brindell M., Stochel G. Bioinorganic photochemistry: frontiers and mechanisms. Chem. Rev. 2005 doi: 10.1021/cr030707e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raja G., Cao S., Kim D.H., Kim T.J. Mechanoregulation of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in cancer therapy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2020;107:110303. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai T.-Y., Lee W.-C. Killing of cancer cell line by photoexcitation of folic acid-modified titanium dioxide nanoparticles. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 2009;204:148–153. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujishima A., Rao T.N., Tryk D.A. Titanium dioxide photocatalysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2000;1:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H., Jeon D., Oh S., Nam K.S., Son S., Chan Gye M. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce apoptosis by interfering with EGFR signaling in human breast cancer cells. Environ. Res. 2019;175:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sree Latha T., Reddy M.C., Muthukonda S.V., Srikanth V.V.S.S., Lomada D. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of anti-cancer activity: shape-dependent properties of TiO 2 nanostructures. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2017;78:969–977. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu X., Mao L., Johnson O., Li K., Phan J., Yin Q. Exploration of TiO2 nanoparticle mediated microdynamic therapy on cancer treatment. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2019;18:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Camargo R., Gutierrez O., Basante M., Criollo W. 2016. Synthesis of Nanomaterials for Medical Purpose - Applications on Cervical Cancer. PCT/IB2015/051143. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roux S., Sablé E., Porsolt R.D. Primary observation (Irwin) test in rodents for assessing acute toxicity of a test agent and its effects on behavior and physiological function. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2005 doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph1010s27. Chapter 10:Unit 10.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Din E.A.A., Mostafa H.E.S., Samak M.A., Mohamed E.M., El-Shafei D.A. Could curcumin ameliorate titanium dioxide nanoparticles effect on the heart? A histopathological, immunohistochemical, and genotoxic study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26:21556–21564. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prior H., Marks L., Grant C., South M. Incorporation of capillary microsampling into whole body plethysmography and modified Irwin safety pharmacology studies in rats. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015;73:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gauvin D.V., Zimmermann Z.J. FOB vs modified Irwin: what are we doing? J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2019;97:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kilkenny C., Browne W., Cuthill I.C., Emerson M., Altman D.G. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlede E., Genschow E., Spielmann H., Stropp G., Kayser D. Oral acute toxic class method: a successful alternative to the oral LD 50 test. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deora P., Mishra C., Mavani P., Asha R., Rajesh K.N. Effective alternative methods of LD50 help to save number of experimental animals. J. Chem. Pharmaceut. Res. 2010;2:450–453. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saganuwan S.A. A modified arithmetical method of Reed and Muench for determination of a relatively ideal median lethal dose (LD50) Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011;5:1543–1546. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai M., Lü B. Tissue preparation for microscopy and histology. Compr. Sampl. Sample Prep. 2012;3:53–93. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng W., Hui Y., Yu J., Wang W., Xu S., Chen C. A new pathological scoring method for adrenal injury in rats with severe acute pancreatitis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2014;210:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price S.J., T Principles for histopathologic scoring. Bone. 2008;23:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruha A.M., Levine M. Central nervous system toxicity. Emerg. Med. Clin. 2014;32:205–221. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belozertseva I.V., Dravolina O.A., Tur M.A., Semina M.G., Zvartau E.E., Bespalov A.Y. Morphine-induced Straub tail reaction in mice treated with serotonergic compounds. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016;791:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang R., Niu Y., Li Y., Zhao C., Song B., Li Y. Acute toxicity study of the interaction between titanium dioxide nanoparticles and lead acetate in mice. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010;30:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu K., Hyuck J., Lee S., Kim J., Kim S., Cho W. Inhalation of titanium dioxide induces endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated autophagy and in fl ammation in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015;85:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi H., Magaye R., Castranova V., Zhao J. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles: a review of current toxicological data. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2013 doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang R., Bai Y., Zhang B., Chen L., Yan B. The potential health risk of titania nanoparticles. J. Hazard Mater. 2012;211–212:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.