Abstract

Inverted papilloma is a rare nasosinusal tumor that mainly occurs in adults during the 5th decade. The occurrence in children is exceptional and only few cases have been reported in the litterature. Clinical and radiological findings mimic other benign nasosinusal pathologies; therefore, diagnosis is based on histopathology either via biopsy or following surgical excision. Here we present a rare case of pediatric inverted papilloma in a 11-year-old child and we discuss clinical, radiological, therapeutic and evolutionary features through a literature review.

Keywords: Inverted, papilloma, pediatric, endoscopic surgery, case report

Introduction

An inverted papilloma (IP) is a rare benign tumor that counts for only 0.5-4% of all nasal neoplasms [1]. IP occurs predominantly in men of the 5th-6th decades of life. It is exceptional in the pediatric population and only a handful of cases have been reported in the litterature [2]. IP is known to be a benign tumor, however, it is caractherized by its recurrency particularly if incompletely removed and its malignant transformation possibility [2]. We report in this paper a case of IP in a child dealed with an endoscopic endonasal removal.

Patient and observation

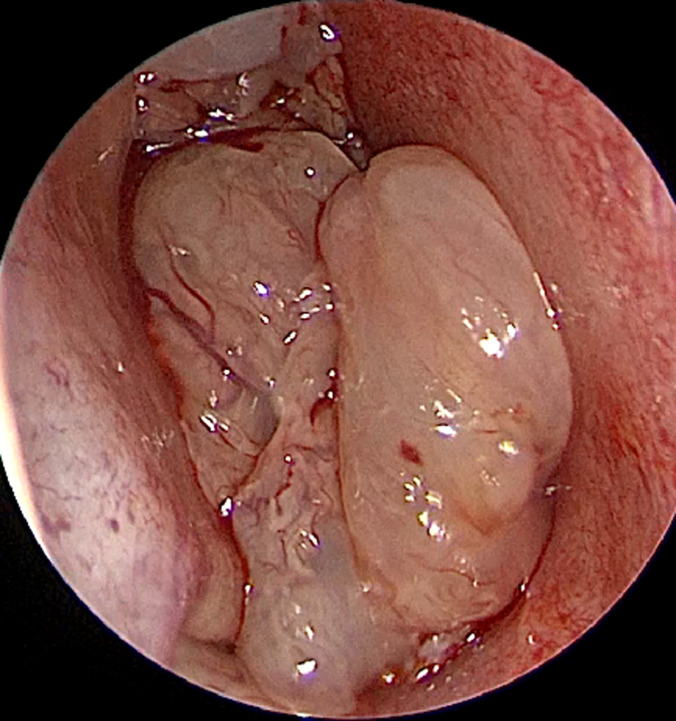

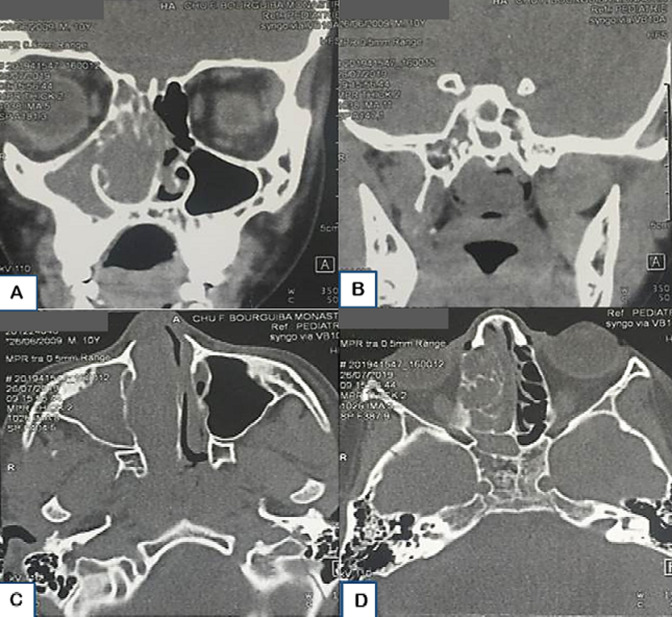

An 11-year-old boy presented to our department with a 12-month history of right-sided nasal obstruction, purulent nasal discharge and posterior rhinorrhea. His medical, surgical and family history was unremarkable. He had no others rhinological symptoms; particularly no epistaxis nor olfactory disorders. Physical examination with nasal endoscopy found a large polypoid mass (Figure 1) filling completely the right nasal cavity extending to the nasopharynx leading to a left septal deviation. Cervical examination did not show any lymphadenopathy. The ophtalmological and neurological exams were normal. Coronal and axial sinus computerized tomography (CT) revealed a complete filling of the right nasal cavity with choanal, nasopharyngeal and right pansinusal extension associated to a controlateral septal deviation. No bony destruction was observed (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

polypoid mass filling the right nasal cavity

Figure 2.

coronal (A, B) and axial (C, D) CT scan showing a large mass of the right nasal cavity with an extension to the choana (A, C) and nasopharynx (B) with a right ethmoidal filling (D)

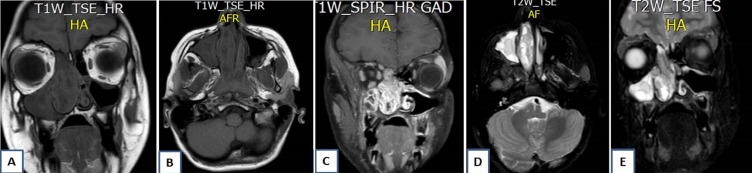

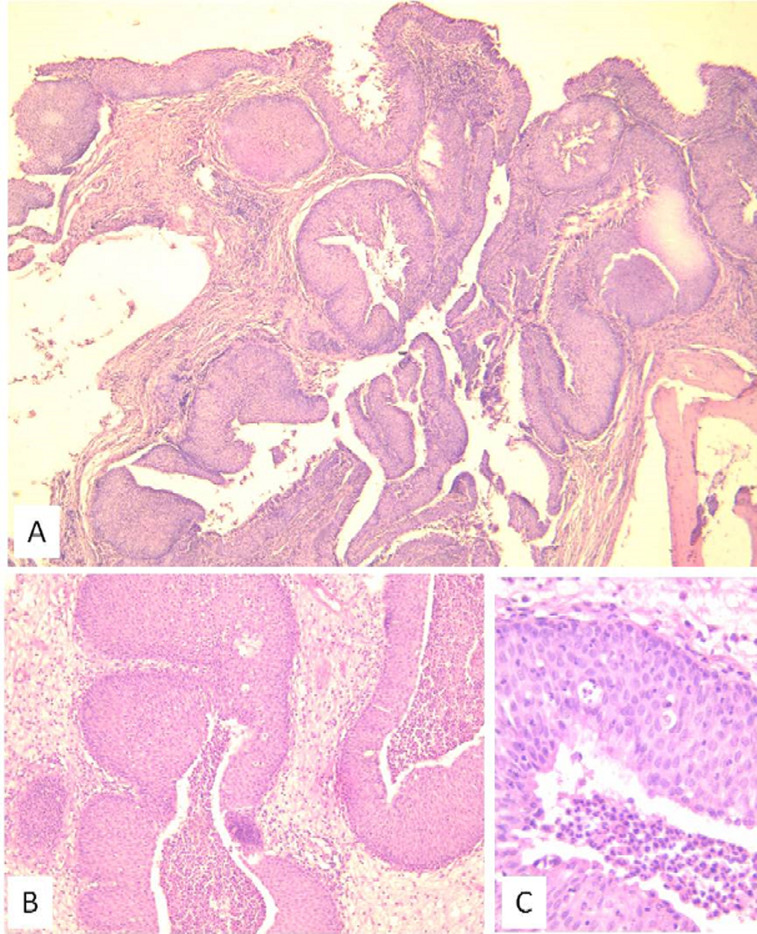

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an ethmoido-nasal mass extending lateraly to the maxillary sinus with a meatal enlargement and posteriorly to the nasopharynx. The lesion appeared in heteregenous signal with a cerebriform aspect and a peripheral enhancement on T1-weighted-gadolinium sequences (Figure 3). The diagnosis of inflammatory mass or angiectasic polyp were evoked. Biopsies were performed and histopathological analysis concluded to the diagnosis of an inflammatory polyp. The patient underwent an endonasal endoscopic surgery under general anesthesia. A large medial meatotomy were performed and the IP diagnosis was made on frozen sections of peroperative specimen, thus a right medial maxillectomy and an ethmoidectomy were achieved with a complete removal of the tumor. The patient was discharged two days after. Microscopally, the tumor was made of thickened epithelial nests arising from the surface and growing down into the stroma confiming the enodophytic growth related to the IP (Figure 4). There was no recurrence after six months of follow-up.

Figure 3.

MR images showing an iso-intense T1-weighted sequence right naso-sinusal mass (A, B) with a peripheral enhancing on T1-weighted-gadolinium sequences (C) and “cerebriform” aspect on T2-weighted sequences (D, E)

Figure 4.

A) (HEx40) endophytic or “inverted” growth pattern consisting of thickened epithelial nests arising from the surface and growing down into the stroma; B) (HEx100) slightly higher magnification showing the endophytic pattern of growth of benign non-keratinizing squamous epithelium; C) (HEx400) the epithelial proliferation is noteworthy of uniformity of nuclei, absence of cytologic atypia and the presence of neutrophils throughout the epithelium

Discussion

Inverted papilloma represents 0.5 to 4% of polypoid lesions of the nose and paranasal sinuses. It characteristically presents in the 5th and 6th decades of life, with a 3: 1 male predilection [1]. IP has rarely been described in the pediatric population. Many large literature studies on inverted papillomas did not report any pediatric case, arguing the paucity of those pathological entities in children and adolescents; Hyam´s landmark study of 149 patients with sinonasal IP included no pediatric cases [3]. Eavey [4], provided the first detailed description in the only published case series of IP in children and adolescents, which included 3 patients aged 6, 9 and 12 years; and two adolescents aged 20 years.

IP in children occurs predominantly in males. Ages range from 6 to 15 years and arise most commonly from the maxillary sinus, nasal septum and also the middle turbinate (Table 1). Our patient was 11 years old. IPs are recognized as benign tumors, with the potential of malignant transformation and recurrence after surgery [2]. In the rare cases reported in children, there has been only one case of malignancy. It was a 20-year-old female who developed low-grade squamous cell carcinoma with an inverted papilloma pattern [4]. Macroscopically IP appear as irregular polypoid masses of variable consistency, pink or gray in color [5]. Histologically, it is characterized by thickened neoplastic epithelium inverted into the underlying connective tissue with an intact basement membrane. The tumor epithelium is composed of well differentiated columnar or ciliated respiratory epithelium with variable squamous differentiation [6].

Table 1.

pediatric cases of inverted papilloma literature review

| Age (years) | Sex | Locations | Surgery | Follow-up | Recurrence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stanley (1984) | 10 | Male | Right inferior turbinate | Caldwell-Luc and ethmoidectomy | 2 years | None |

| Eavey (1985) | 6 | Male | Right septum | Intranasal removal | Lost | None |

| 9 | Female | Right nasal cavity, maxillary and ethmoid sinuses | Lateral rhinotomy and medial maxillectomy | 2½ years | None | |

| 12 | Male | Right nose and sinuses | Lateral rhinotomy, medial maxillectomy and sphenoidotomy | 2 years | None | |

| Limaye (1989) | 15 | Female | Left nasal cavity and maxillary sinus | Lateral rhinotomy, ethmoidectomy and antrostomy | 3½ years | At 12 months |

| 10 | Male | Inferior portion of the lateral nasal wall the floor of the nose, the inferior half of the septum and the vestibule | Lateral rhinotomy and laser vaporization | 13 months | At 10 months | |

| Anthony J D'Angelo (1992) | 12 | Male | Right nasal cavity and maxillary antrum | Caldwell-Luc procedure with a partial medial maxillectomy | 1 years | None |

| Cooter (1998) | 10 | Male | Posterior border of the maxillary os, the medial maxillary sinus wall and a portion of the inferior turbinate | Maxillary antrostomy, anterior ethmoidectomy, and partial inferior turbinectomy | 1 year | None |

| Özcan (2005) | 9 | Female | Left inferior concha and lateral nasal wall | Endoscopic resection and Caldwell-Luc procedure (operated two times for the left intranasal mass) | 10 months | None |

| Cho (2008) | 15 | Male | Left sphenoid sinuses | Transnasal endoscopic resection | 2 years | None |

| Jayakody (2018) | 11 | Male | Right nasal cavity and Sinuses (origin: postero-lateral wall of the maxillary sinus) | Transnasal endoscopic resection | 5 years | None |

| Our case (2020) | 11 | Male | Right nasal cavity, maxillary and ethmoid sinuses | Transnasal endoscopic large medial maxillectomy with ethmoidectmy | 6 months | None |

Aetiopathogenis of IP remains icompletely understood, however, some etiologic factors such as chronic rhinosinusitis, proliferation of nasal polyps, allergy, environmental pollutants, tobacco and viruses particularly the human papilloma virus (HPV) have been reported in the literature, however, no significant evidence for this theory exists [2]. The signs and symptoms of IP in children are indistinguishable from other unilateral pediatric nasal masses and most commonly include unilateral nasal obstruction, nasal discharge, epistaxis. Headache, diplopia, epiphora or hyposmia suggest invasion into adjacent structures. Further, no single symptom or sign can be statistically linked to carcinoma within a papilloma [7,8]. The cases of IP reported in children showed no substantial differences in its clinical behavior or histologic features compared to IP in adults. Although a significant number of pediatric cases reported were diagnosed after a prior recurrence [4].

Imaging investigations with CT scan and MRI are necessary to analyze nasosinusal masses. In typical cases IP arise from medial wall of nasal cavity (exactly from middle meatal) and extent to maxillary sinus. We can observe intralesional calcifications and/or bone thinning or erosion [2,7]. Maxillary sinus is most commonly involved, but the ethmoidal, frontal and sphenoid sinuses may also be affected. On MRI a convoluted cribriform pattern is highly suggestive of IP [2,9]. In our case, the cerebriform aspect observed on the MRI was suggestive. But the diagnosis of IP was not mentioned by the radiologist and an inflammatory mass or an angiectasic polyp were suspected.

Before surgery, pathologic examination is essential to diagnosis. IP may coexist with an inflammatory process showing inflammatory polyps. This accounts for the false negative rates of up to 17% on biopsy reported in the literature [10]. In our case the analysis of preoperative biopsy showed an iflammatory lesion which was certainly a sentinel polyp. In a case of unilateral polyp, sinonasal tumor, particularly IP, should be always suspected [10]. The locally aggressive behavior and the potential of malignancy of IP explain that the only curative treatment of such tumors in adults is surgery [10-15]. In pediatric population, the treatment seems to be the same as in adults. No particularities in the management approach of pediatric IP have been reported in the several cases of the literature [10-15].

Extra-nasal approach was the “gold standard” to perform the “en bloc” resection of the tumor for about 35 years. Whereas, since the development of the endonasal endoscopic surgery, along the last years, mini-invasive techniques are more and more used. The endoscopic medial maxillectomy and its varieties became the essential way to remove IP [11]. It provides a wide access to specific nasal areas and better visualization of the anatomical stuctures. Compared to open approaches, the endoscopic medial maxillectomy had shown advantages of shorter hospital stay with less complications and similar success rates [12].

Recurrences occurs especially in cases of incomplete resection explained by a poor exposure and visualization of the tumor´s limits. They generally appear within 6 months after surgery, however, cases of IP recurrence have been reported 20 years after in the literature [8]. The recurrence rate of IPs in adults ranges between 14 and 78% [2]. In the pediatric cases, Limaye [13] noted a recurrence in his two cases reported after 10 and 12 months. Özcan [7] reported also, a case of a recurrent IP in a 9-year-old child (Table 1). Endocopic examination at clinical controls is the main way to detect recurrence and thus provide minimal surgery when they are still small-sized [7].

Conclusion

Although it is exceptional, IP should be evoked as diagnosis of unilateral nasal masses in children. Failure to consider this entity may lead to inadequate treatment and risk of recurrence. Pediatric IP shows clinically, radiologically and pathologically similarities to the adult one thus the diagnosis and treatment approches seem to be the same. Since recurrences can occur after a long period of time, life-long follow-up is required.

Footnotes

Cite this article: Amel El Korbi et al. Pediatric naso-sinusal inverted papilloma: report of a case and literature review. Pan African Medical Journal. 2020;37(373). 10.11604/pamj.2020.37.373.27186

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Amel El Korbi and Sondes Jellali: manuscript writing and bibliography selecting; Naourez Kolsi, Rachida Bouatay, Mehdi Ferjaoui and Emna Berguaoui: bibliography selecting; Leila Njim: iconography selecting; Khaled Harrathi, Jamel Koubaa: manuscript revision. All the authors have read and agreed to the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Cho H-J, Kim J-K, Kim K-S, Chun J-Y, Yoon J-H. An inverted papilloma isolated to the sphenoid sinus in a pediatric patient. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2008;3(3):124–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jayakody N, Ward M, Wijayasingham G, Fowler D, Harries P, Salib R. A rare presentation of a paediatric sinonasal inverted papilloma. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018(11):rjy321. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjy321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyams VJ. Papillomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: a clinicopathological study of 315 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1971;80(2):192–206. doi: 10.1177/000348947108000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eavey RD. Inverted papilloma of the nose and paranasal sinuses in childhood and adolescence. Laryngoscope. 1985;95(1):17–23. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khandekar S, Dive A, Mishra R, Upadhyaya N. Sinonasal inverted papilloma: a case report and mini review of histopathological features. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2015;19(3):405. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.174644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M-J, Noel JE. Etiology of sinonasal inverted papilloma: a narrative review. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;3(1):54–8. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Özcan C, Görür K, Talas D. Recurrent inverted papilloma of a pediatric patient: clinico-radiological considerations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(6):861–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Angelo AJ, Jr, Marlowe A, Marlowe FI, McFarland M. Inverted papilloma of the nose and paranasal sinuses in children. Ear Nose Throat J. 1992;71(6):264–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeon TY, Kim H-J, Chung S-K, Dhong H-J, Kim HY, Yim YJ, et al. Sinonasal inverted papilloma: value of convoluted cerebriform pattern on MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(8):1556–60. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lisan Q, Laccourreye O, Bonfils P. Sinonasal inverted papilloma: from diagnosis to treatment. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2016;133(5):337–41. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasquini E, Sciarretta V, Farneti G, Modugno GC, Ceroni AR. Inverted papilloma: report of 89 cases. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(3):178–85. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishak MN, Lazim NM, Ismail ZIM, Abdullah B. Open and endoscopic medial maxillectomy for maxillary tumors-a review of surgical options. Curr Med Issues. 2019;17(3):75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Limaye AP, Mirani N, Kwartler J, Raz S. Inverted schneiderian papilloma of the sinonasal tract in children. Pediatr Pathol. 1989;9(5):583–90. doi: 10.3109/15513818909026917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanley RJ, Kelly JA, Matta II, Falkenberg KJ. Inverted papilloma in a 10-year-old boy. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984;110(12):813–5. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1984.00800380043012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooter MS, Charlton SA, Lafreniere D, Spiro J. Endoscopic management of an inverted nasal papilloma in a child. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118(6):876–9. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70289-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]