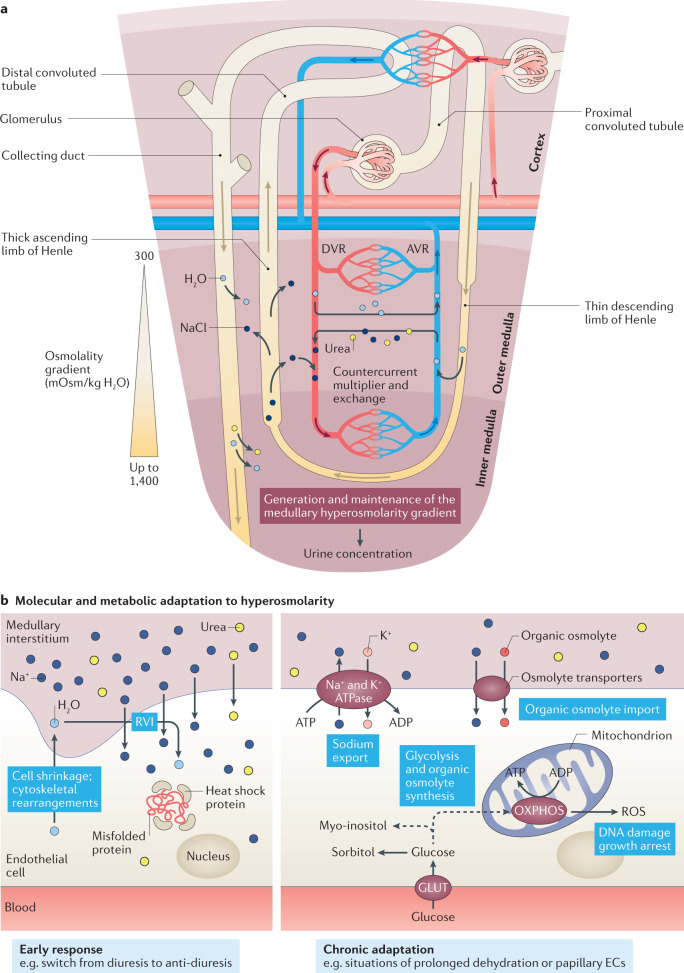

Fig. 6. Response of the renal endothelium to changes in osmolarity.

a | The renal medullary and papillary regions of the kidney are exposed to hyperosmolarity as a consequence of the countercurrent multiplier and exchange mechanisms, which generates and maintains the medullary hyperosmolarity gradient (ranging from 300 mOsm/kg H2O at the corticomedullary junction to up to 1,400 mOsm in the papilla) that drives the process of urine concentration. b | In response to a rapid increase in osmolarity (for example, following a switch from diuresis to anti-diuresis) endothelial cells (ECs) tend to shrink as a consequence of water loss. This response results in cytoskeletal rearrangements and activation of a regulatory volume increase (RVI) compensatory mechanism, characterized by an accumulation of intracellular Na+ and urea followed by osmotic water reabsorption. Moreover, the expression of heat shock proteins is induced to preserve the correct folding of proteins from high levels of denaturing urea (left panel). Prolonged exposure to hyperosmolarity, such as occurs in the papilla or during situations of prolonged dehydration, induces ECs to promote the production of ATP from oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), and stimulate active Na+ export through the Na+/K+ ATPase as well as the import and synthesis of inert organic osmolytes (such as glucose-derived polyols) to protect the cell from hyperosmolarity-induced cell damage (right panel). AVR, ascending vasa recta; DVR, descending vasa recta; GLUT, glucose transporter; ROS, reactive oxygen species.