Abstract

For 150 years artificial stimulation has been used to study the function of the nervous system. Such stimulation—whether electrical or optogenetic—eventually may be used in neuroprosthetic devices to replace lost sensory inputs and to otherwise introduce information into the nervous system. Efforts toward this goal can be classified broadly as either biomimetic or arbitrary. Biomimetic stimulation aims to mimic patterns of natural neural activity, so that the subject immediately experiences the artificial stimulation as if it were natural sensation. Arbitrary stimulation, in contrast, makes no attempt to mimic natural patterns of neural activity. Instead, different stimuli—at different locations and/or in different patterns—are assigned different meanings randomly. The subject’s time and effort then are required to learn to interpret different stimuli, a process that engages the brain’s inherent plasticity. Here we will examine progress in using artificial stimulation to inject information into the cerebral cortex and discuss the challenges for and the promise of future development.

Keywords: cerebral cortex, electrical stimulation, intracortical microstimulation, perception, sensation

Utilization of the neural elements of the cerebral cortex directly as receptors for conditional stimuli greatly extends the possible application of neurological techniques in the study of behavior. With this procedure the intricate and largely unknown elaboration of sensory data by the afferent system can be by-passed …

Since the mid-19th century, when Fritsch and Hitzig evoked body movements somatotopically using electrical stimulation of a limited region of the canine cortex (Fritsch and Hitzig 1870), artificial stimulation has been used to study the function of the nervous system. In the 20th century, electrical stimulation was employed extensively to evoke and modify behavior—from investigating the cortical fields that control movement (Andersen and others 1975; Asanuma and Rosen 1972), to providing positive reinforcement (Olds and Milner 1954). Now in the 21st century, as brain-computer interfaces are being developed to restore lost function to individuals affected by injury, disease, or developmental disorder (Bockbrader and others 2018; Loeb 2018; Tsu and others 2015), artificial excitation of the nervous system can provide a means of introducing into the nervous system information that cannot enter through normal pathways.

In the present review we will examine current knowledge regarding artificial injection of specific, discriminable information into the nervous system, point out some of the challenges in making this an effective tool for studying nervous system function, and speculate on future developments. To focus on injecting information, we will minimize discussion of how stimulation has been used to investigate the normal functions of the nervous system. And although stimulation of subcortical and peripheral parts of the nervous system has great potential for delivering information artificially into the nervous system—as exemplified by the cochlear implant (Sun and others 2019)—here we will focus instead on injecting information into the mammalian cerebral cortex. Compared to stimulating the peripheral nerves or the deeper, more compact nuclei of the brain, the cerebral cortex historically has offered the advantages of lying largely just beneath the calvarium, making it relatively accessible, and of providing a relatively large target area.

Electrical stimulation is effective, of course, because almost all neurons naturally generate propagating electrical action potentials to transmit information, and such action potentials can be evoked by delivering electrical current artificially. Electrical stimulation therefore can be applied anywhere in the nervous system simply by putting an electrode in the desired location. Electrical stimulation, however, excites not only local neuronal somata but also axons passing through the vicinity even more readily (see Box 1).

Box 1. The Spatial Extent of Intracortical Microstimulation.

A microelectrode tip carefully positioned in the cerebral cortex can record action potentials from a single neuron or just a few neurons. Those unfamiliar with intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) often imagine that pulses of near-threshold current delivered through that microelectrode will evoke action potentials only in that(those) neuron(s). Such is not the case, however, for three basic reasons.

First, even if a single neuron is recorded by the microelectrode, numerous neuron somata in the vicinity will receive suprathreshold stimulation with even single, low-amplitude ICMS pulses. In the initial studies examining the spatial extent of ICMS, one microelectrode was positioned to record a pyramidal tract neuron (PTN) in cat M1 and a second microelectrode was lowered at 25 μm steps past the PTN, identifying the single-pulse (200 μs) cathodal current threshold needed to excite the PTN (Stoney and others 1968). Whereas minimum thresholds of ~1 to 17 μA could excite a PTN at the presumably closest position of the stimulating electrode, ICMS pulses of ~5 to 30 μA at 100 μm above or below this position could still excite the same PTN. Modeling current as falling off with the square of distance from the stimulating electrode, a single 20 μA × 200 μs (4 nC) cathodal pulse was estimated to excite PTNs within an 88 μm radius, which in cat M1 would include ~28 PTNs. PTNs are typically the largest neurons in the cortex, however. Subsequent studies have estimated that as many as 2175 additional low-threshold neurons may be excited directly by 10 μA × 200 μs (2 nC) pulses (Tehovnik 1996). In comparison to these near-threshold currents, substantially larger currents—up to 100 μA or even 500 μA—often have been employed in studies examining behavioral effects.

Second, besides the local neuron somata, their dendrites, and their axon initial segments, axons passing through the local neuropil will be stimulated (Nowak and Bullier 1998a, 1998b; Ranck 1975). In rat S1, single 8 μA × 100–600 μs (0.8–4.8 nC) pulses antidromically excite somata at distances up to 1350 μm (Butovas and Schwarz 2003). In cat visual cortex where lateral axons are known to extend several millimeters in layers 2/3, ICMS with trains of 10 μA × 200 μs (2 nC) pulses can activate somata up to 4 mm away (Histed and others 2009). Note that in addition to axons originating from local somata, axons arriving from other cortical areas and subcortical regions will be activated. Stimulating axons can both antidromically excite their somata of origin and orthodromically deliver postsynaptic potentials to their target neurons.

And third, much if not most of the effects of ICMS are trans-synaptic. In monkey M1 and F5 (ventral premotor cortex), single pulses of ≤400 μA × 200 μs (≤80 nC) evoke action potentials in corticospinal neurons most often only at latencies consistent with indirect (i.e., trans-synaptic) rather than direct activation (Maier and others 2013). Repetitive trains of ICMS pulses, by producing temporal summation of successive EPSPs, provide the opportunity for trans-synaptic excitation of additional neurons, even through oligo-synaptic linkages. In rodent agranular sensorimotor cortex, excitation of most intracellularly recorded layer 5 pyramidal neurons by ICMS trains (13 pulses of up to 60 μA × 200 μs (12 nC) at 333 Hz) delivered 100–150 μm away is abolished during blockade of synaptic transmission, demonstrating that most of the local activation normally produced by trains of ICMS is trans-synaptic (Hussin and others 2015). One of the earliest applications of ICMS provides perhaps the most overt example (Asanuma and Ward 1971). Trains of 4 to 20 μA × 200 μs (0.8–4.0 nC) ICMS pulses delivered at 300 Hz in the motor cortex of cats elicited overt contractions of forearm muscles. Cats have no monosynaptic connections from cortical neurons to spinal motoneurons. So such trains of ICMS pulses delivered in the cortex excited pools of spinal motoneurons through at least di-synaptic linkages from the cortex.

In recent years artificial excitation also has been produced optogenetically (Deisseroth 2015; Deng and others 2018; Galvan and others 2017). Optogenetic stimulation requires genetic manipulation to transduce neurons such that they express photoreceptor-linked membrane channels (channelrhodopsins). Illuminating transduced neurons with light of the appropriate wavelength then produces depolarization sufficient to trigger action potentials. While requiring genetic manipulation, optogenetics can achieve selective stimulation of specific types of neurons, which electrical stimulation cannot. But optogenetic stimulation has yet to be used extensively to inject specific, discriminable information into the nervous system, and the present review therefore will emphasize electrical stimulation.

We will distinguish two alternative approaches to injecting information using artificial excitation—biomimetic and arbitrary. The biomimetic approach endeavors to mimic the natural activity of neurons insofar as possible. Biomimetic stimulation is thought to have the advantage of seeming as natural as possible to the intact portions of the nervous system, thereby minimizing the cognitive burden of learning to interpret an artificial input. In the near future, however, biomimetic stimulation—whether electrical or optogenetic—is unlikely to be capable of reproducing the asynchronous action potentials in large numbers of cortical neurons that characterize the normal spatiotemporal patterns of neural activity naturally involved in any complex percept.

In contrast, the arbitrary approach makes no attempt to mimic the normal, natural patterns of neural activity. Instead, different artificial stimuli are associated randomly with different pieces of information, and the inherent ability of the nervous system to learn through adaptive, plastic processes is called upon to make the different, arbitrarily assigned patterns of stimulation interpretable. Arbitrary stimulation removes the need to emulate the natural neural activity underlying specific behaviors, and instead puts the burden of learning to interpret the incoming information on the subject’s own nervous system. While arbitrary stimulation lacks the long-term promise of accurately recreating percepts, in the short-term it may be as effective as biomimetic stimulation for injecting specific, discriminable information.

Biomimetic Stimulation

Somatosensory Cortex

Since the early report of two cases studied by Cushing, electrical stimulation of the surface of the postcentral gyrus in awake humans has been known to evoke somatic sensations (Cushing 1909). Subsequent studies have found that, although the evoked perceptions may include motion of a specific body part or stroking of the skin, subjects most commonly describe the evoked sensation as “numbness” and/or “tingling” (Penfield and Boldrey 1937; Penfield and Rasmussen 1950; Roux and others 2018). These artificially evoked sensations thus are similar to the abnormal sensations we all experience when a nerve “goes to sleep” as the result of temporary ischemia from external pressure or local anesthesia, and then subsequently recovers. But in contrast to the numbness and tingling evoked by stimulation through electrodes placed on the surface of the postcentral gyrus, electrical stimulation through microelectrodes inserted into the cortical gray matter (intracortical microstimulation or ICMS) in the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) has been found to produce cutaneous sensations comparable in certain respects to natural stimulation of the skin.

A number of distinct features of natural tactile stimulation delivered to the skin surface have been produced with ICMS in S1. In perhaps the earliest demonstration of biomimetic stimulation, monkeys initially were trained to indicate whether the second of two “fluttering” mechanical vibrations (in the range of 10–36 Hz) delivered to the skin of a fingertip was higher or lower in frequency than the first (Romo and others 1998). The monkeys were trained to perform this task as accurately as possible, typically distinguishing frequency differences as small as 8 Hz (e.g., 28 Hz vs. 36 Hz) correctly more than 75% of the time (Fig. 1). ICMS in S1 then was delivered (through microelectrodes positioned near quickly adapting neurons in area 3b) in place of the second mechanical vibration. The frequency of doublet pulses of electrical stimulation was in the same range as the frequency of the mechanical flutter/vibration applied to the skin. The monkeys could accurately indicate whether the second stimulus was higher or lower in frequency than the first stimulus when the second stimulus was either ICMS or a mechanical vibration of the fingertip. The monkeys thus discriminated the frequency of the ICMS as if it were the mechanical stimulus. Interestingly, when the ICMS was made aperiodic—delivering doublets at random intervals but with the same number of doublets during the 500 ms stimulus—the animals continued to discriminate the average frequency accurately.

Figure 1.

Biomimetic ICMS perceived as vibration. (A) Experimental paradigm. Within 1 second of when the mechanical probe indented a fingertip (probe down—PD), the monkey placed its other hand on a home key (key down—KD). After a delay, the mechanical probe oscillated at the base frequency, and after an interstimulus interval either a second mechanical stimulus (blue) or a train of ICMS (orange) was delivered at the comparison frequency. The monkey then released the home key (key up—KU) and pressed one of two push-buttons (PB) indicating that the comparison frequency was higher or lower than the base frequency. (B) Percent correct using mechanical (blue bars) versus ICMS (orange bars) comparison stimuli with 8 Hz frequency differences. Base frequencies (violet) are shown in the upper row of numbers, comparison frequencies (green) in the lower row. (C) Performance with a base frequency of 20 Hz as the comparison frequency was varied (blue circles—mechanical; orange circles—ICMS). Reproduced with permission from Romo and others (1998).

Additional recent studies extending such work to area 1 as well as area 3b have shown that the frequency of ICMS pulses in either area can be discriminated up to 200 Hz, and that increasing ICMS current (up to 100 μA) is perceived as being comparable to increasing the pressure and depth (up to 2000 μm) to which the skin is indented mechanically (Callier and others 2020; Tabot and others 2013). At some electrodes, however, high pulse frequencies can change the perceived magnitude of the stimulation. Furthermore, when ICMS is delivered in the somatotopic representation of different fingertips (identified by the local neural responses to natural tactile stimulation) monkeys can discriminate the somatic location of mechanical versus ICMS stimuli (Tabot and others 2013).

Importantly, in these studies of biomimetic S1 ICMS in nonhuman primates, the monkeys performed the discriminations as soon as ICMS trains were substituted for mechanical stimulation. The monkeys had no opportunity to learn to interpret the artificial stimuli. ICMS in S1 thus can be biomimetic for vibration frequency, pressure magnitude, and skin location. Beyond these passively perceived features, monkeys also have discriminated grating textures mimicked by delivering an ICMS pulse in S1 each time the fingertip of an actively exploring avatar hand (controlled by the monkey with either a joystick or a BCI) encountered a virtual ridge at spatial frequencies of 0.5 to 4.0/cm, which requires integrating the frequency of ICMS pulses with knowledge of the speed of hand motion (O’Doherty and others 2019). In this texture discrimination task the monkeys’ performance was above chance from the outset, but improved further with experience. Whether other features of tactile stimulation—such as temperature, or motion across the skin surface—can be produced biomimetically with artificial stimulation has yet to be determined.

In humans as well, ICMS in S1 can produce naturalistic sensations. A human subject was able to discriminate which finger region in S1 was being stimulated (Flesher and others 2016). The subject most often described the sensation produced by S1-ICMS in areas 1 and 2 as “pressure.” Increasing ICMS current from 10 up to 80 μA produced a linear increase in the perceived intensity of the pressure, consistent with the earlier finding in macaques (Tabot and others 2013). Yet when asked to rate the naturalness of the stimulus, the subject gave a rating only midway between totally natural and totally unnatural 95% of the time.

This “partially natural” quality may reflect a limitation of biomimetic stimulation. Single ICMS pulses synchronously excite a large number of neural elements distributed over a substantial local area, and trains of pulses can excite neural elements at a distance (see Box 1). Although local and long-range synchrony occur naturally among inhibitory interneurons (Buzsaki and Wang 2012; Swadlow and others 1998), widely distributed synchronous activation of large populations of excitatory neural elements, though pathophysiologic in seizure disorders (Chauvette and others 2016), rarely if ever occurs in the natural physiology of normal, healthy cortex. So percepts generated by ICMS, even biomimetic ICMS, may not be experienced as entirely natural.

Visual Cortex

In the visual cortex, electrical stimulation evokes the percept of a small spot of light, termed a “phosphene.” Phosphenes are evoked with stimulation at the cortical surface through electrocorticographic electrodes or with ICMS (Bosking and others 2017; Dobelle 2000; Tehovnik and Slocum 2013; Winawer and Parvizi 2016). In normally sighted human subjects, ICMS within 2 cm of the occipital pole (most likely in primary visual cortex, V1) produces phosphenes which subjects describe as small (1–2°), brightly colored (blue, yellow, or red) spots of light at locations in the visual field that depend on the location of the electrode in the retinotopic map (Bak and others 1990; Schmidt and others 1996). Theoretically, very low current stimulation could evoke phosphenes with additional features of cortical columns, such as line orientation (Tehovnik and others 2009; Troyk and others 2003). Phosphenes thus can have the biomimetic properties of color and retinotopic location, and potentially other features as well.

Phosphenes reveal a second challenge for biomimetic stimulation, however, having to do with what we might term “interaction” with normal neural activity. In normal vision, a complex network integrates shifting retinal images as the eyes move to foveate various stationary or moving objects, thereby providing a stable visual scene (Wurtz 2008). Human subjects report, however, that phosphenes appear to jump around in the earth-based reference frame when the subject makes saccadic eye movements, that is, phosphenes maintain their retinotopic location when the eyes move. Phosphenes induced by ICMS thus fail to engage the normal scene-stabilizing network. To provide a stable visual scene, therefore, biomimetic stimulation in the primary visual cortex may require additional stimulation that somehow engages the scene-stabilizing network. Furthermore, although one might think that simultaneous stimulation at multiple points selected to approximate a shape (e.g., a circle) would evoke the visual percept of the appropriate shape immediately, instead subjects initially perceive multiple separate phosphenes (Najarpour Foroushani and others 2018). Interestingly, interleaved ICMS pulses on nearby electrodes can produce the percept of a single fused shaped (Bak and others 1990), so it may be the well-known phenomenon of surround inhibition that creates separate phosphenes when pulses are delivered simultaneously (Tanaka and others 2019). Only after considerable experience have human subjects learned to recognize relatively simple shapes such as printed letters evoked by simultaneous artificial stimulation at multiple cortical points (Dobelle 2000).

Hippocampus

In the somatosensory and visual examples described above, stimulation was delivered through a given electrode to evoke a particular percept. But artificial stimulation also can be delivered at multiple locations in complex spatiotemporal patterns. Perhaps the most sophisticated application of biomimetic spatiotemoporal electrical stimulation has been applied in the hippocampus to enhance short-term memory in rodents and nonhuman primates (Deadwyler and others 2017). Multiple electrodes (tetrodes) were placed in both the CA3 input field of the hippocampus and in the corresponding region of the CA1 output field, which receives strong input from CA3 via the Shaffer collaterals. A nonlinear, dynamic, multiple-input/multiple-output (MIMO) model was trained to record the responses of neurons in CA3 and deliver ICMS pulses that mimicked the corresponding spatiotemporal pattern of spikes discharged by neurons at the CA1 electrodes. The monkeys had been trained to perform a delayed-match-to-sample task that incorporated varying numbers of distractors and required the monkeys to remember the sample for various time delays. Using the MIMO model to determine the spatiotemporal pattern of the pulses, ICMS then was delivered in CA1 based on the activity recorded in CA3 during presentation of the sample. Exactly how this biomimetic ICMS interacts with the ongoing natural activity of the hippocampus remains unclear, but delayed matching performance improved substantially: with multiple distractors and at any given delay interval, the monkeys were more likely to match the sample correctly. For example, with MIMO stimulation monkeys could remember at delays of 30 to 40 seconds as well as they could at delays of 10 to 20 seconds without stimulation. MIMO-model hippocampal stimulation recently has been shown to improve delayed recall in human subjects as well (Hampson and others 2018).

Interestingly, in the monkey studies the investigators noticed that within a given session the enhanced memory performance persisted for a considerable number of trials after delivery of MIMO-ICMS was discontinued (Deadwyler and others 2017). This persistent effect of MIMO-ICMS indicates a third limitation on biomimetic stimulation: plastic changes produced in the hippocampus or elsewhere in the nervous system outlasted the duration of the artificial stimulation. ICMS is known to produce long-term potentiation and long-term depression in the hippocampus and in the sensorimotor cortex (Castro-Alamancos and Connors 1996; Hess and Donoghue 1999; Iriki and others 1989; Kitagawa and others 1997; Nicoll 2017; Pinar and others 2017; Teskey and others 2007). Furthermore, when triggered to occur at short intervals near spontaneous spikes in motor cortex for 1 to 4 days, ICMS has been shown to be capable of inducing spike-timing dependent synaptic plasticity that can last for several days after the artificial stimulation is stopped (Bi and Poo 2001; Guggenmos and others 2013; Jackson and others 2006; Nishimura and others 2013; Rebesco and Miller 2011; Rebesco and others 2010). Additionally, training monkeys to detect ICMS in the primary visual cortex raises the threshold for detection of visual stimuli at the corresponding retinotopic location (Ni and Maunsell 2010). Through such mechanisms, biomimetic stimulation in any cortical area—including sensory areas that have previously reorganized after prolonged deafferentation (Flesher and others 2016; Pons and others 1991)—inadvertently may induce some degree of plastic reorganization in the nervous system, altering the perception evoked by the otherwise biomimetic stimulus.

Another Challenge for Biomimetic Stimulation in Any Cortical Area

Although we have brought out different challenges for biomimetic stimulation—achieving naturalness, integrating with normal function, and avoiding plastic changes—in relation to different cortical areas, all these issues are likely to arise with artificial stimulation anywhere in the cortex. Still another challenge for biomimetic stimulation regardless of the target cortical area will be to deliver spatiotemporally patterned stimulation at multiple sites in such a way that the subject experiences a complex percept (Overstreet and others 2016). When you use multiple fingertips to pick up an object, for example, you can instantly judge its size and shape, as well as whether it is hard or soft, rough or smooth, warm or cold, which allows you instantly to know whether you are holding a cup of hot tea or an ice cube. Such complex perceptions require integration of input from different types of cutaneous receptors in each fingertip, as well as proprioceptive inputs from the joints and muscles of the fingers. Although biomimetic ICMS may be able to create percepts of flutter frequency and pressure at different points on the skin, whether appropriate spatiotemporal patterns of ICMS at multiple electrodes can be integrated into a more complex percept of an object with specific size, shape, and texture has yet to be determined. To what extent will appreciation of such complex percepts be intuitive and immediate versus learned through practice over time?

Likewise, can stimulation in visual cortex be delivered such that subjects fuse multiple phosphenes into the image of a numeral or a face without considerable learning? The concept of delivering a pixelated image using biomimetic stimulation through an array of electrodes implanted in visual cortex might seem straightforward. But efforts to date have been primarily arbitrary, in that an electrode grid placed over both primary and higher order visual cortex typically does not stimulate the cortex in a well-ordered retinotopic mapping. Nevertheless, implanted human subjects have learned to use such visual neuroprostheses to discriminate a variety of visual shapes (Dobelle 2000). Of note, when the image is acquired with a head-mounted camera, the subject scans the shape using active head movements, that is, the subject does not recognize the shape using a single, stationary pattern of phosphenes. Rather the subject artificially “looks around,” creating a dynamically changing pattern of phosphenes, to recognize a visual shape.

Yet to be explored is the possibility of delivering biomimetic stimulation in complex spatiotemporal patterns in higher order sensory areas such as the secondary somatosensory area or the fusiform face area. Conceivably more complex percepts might be elicited by biomimetic stimulation in these areas. But we have yet to understand the patterns of normal neural activity that provide such complex percepts. Beyond processing peripheral input through sequentially hierarchical cortical areas, these percepts may involve multiple stages of cortico-thalamo-cortical processing (Sherman 2016) and may be modulated by both bottom-up and top-down attention (Katsuki and Constantinidis 2014). Whether mimicking activity in a primary sensory receiving area with ICMS will suffice to evoke a naturalistic complex percept, or whether mimicry of additional processing stages and modulatory influences will be needed as well, remains unknown.

Advances with Optogenetic Biomimetic Stimulation

To date, optogenetic approaches have provided behavioral examples primarily of detection of a single stimulus rather than discrimination of different stimuli. For example, optogenetic stimulation in S1 has been shown to be detected both in mice (Huber and others 2008) and in monkeys (May and others 2014). Recently, however, mice have discriminated optogenetic stimulation of visual cortex that biomimetically emulated the natural spatiotemporal patterns of neural activity occurring as they viewed vertical versus horizontal moving gratings (Marshel and others 2019). Achieving this result employed two major technical advances. First, a fast channelrhodopsin, ChRmine, was identified, enabling effective optogenetic stimulation in the millisecond time frame. Second, holographic laser stimulation was developed to stimulate multiple targeted neurons in different layers throughout the cortical depth asynchronously. Mice initially were trained in a Go/No-Go paradigm to lick a spout for a water reward when a vertical grating appeared, but not to lick and thereby avoid an air puff when a horizontal grating appeared. Population neuronal responses to vertical versus horizontal gratings then were recorded. Without the visual gratings to view, using only optogenetic playback of the recorded activity patterns, the mice then could perform the Go/No-Go task as if they were still seeing the gratings. In the future, such optogenetic approaches may go far in extending studies that currently employ biomimetic electrical stimulation.

Arbitrary Stimulation

Limitations on the extent to which stimulation can emulate the natural activity of the nervous system raise the question of whether stimulation used to inject information into the cortex must necessarily be biomimetic at all. Could arbitrary stimulation that makes no attempt to reproduce natural neural activity be useful?

To a certain extent, this question has been approached noninvasively by using one sensory modality to replace another, often referred to as “sensory substitution.” When a blind person reads Braille, for example, he or she uses natural tactile sensation to substitute for the vision used by sighted individuals. The various configurations of raised dots that form the Braille alphabet are designed to be recognized easily with touch, not to emulate the shape of visually perceived letters. Braille thus uses an arbitrary tactile representation of the “normal” visual alphabet. And in a deeper sense, all alphabets substitute another sensory modality for the way in which the human cortex naturally receives language input: listening to someone else speak.

The idea that information normally arriving in the nervous system through vision can be delivered instead through touch has been extended by stimulating the skin either mechanically through an array of vibrotactile devices or else electrically through an array of surface electrodes (Bach-y-Rita 2004). Using such arrays, a pixelated representation of the image from a video camera can be delivered to the skin. With such a tactile vision substitution system, human subjects can learn to identify the direction in which an object moves, and even to perceive faces, although perception at this level is probably far from our normal ability to recognize complex visual images immediately.

Arbitrary Stimulation in S1 to Substitute for Vision

Combining the idea that tactile sensation can substitute for vision with the concept that ICMS in S1 can evoke tactile percepts has led to studies in which S1 ICMS has been used to substitute for cues that might otherwise be delivered visually. Rats have been trained to turn either rightward or leftward when ICMS was delivered in the right or left S1 whisker cortex (Talwar and others 2002). Owl monkeys have learned to interpret different spatial or temporal patterns of ICMS in the S1 hand representation as cues to find food behind a right versus a left door (Fitzsimmons and others 2007), or to move a cursor to a right or left target using either hand control of a joystick or brain control of a cursor (O’Doherty and others 2009). And Rhesus monkeys actively exploring a workspace learned to hover a cursor over one of three visually identical targets when a particular rewarded pattern of S1 ICMS was delivered, rather than an alternate unrewarded pattern or no ICMS at all (O’Doherty and others 2011). In all of these studies, rather than delivering ICMS in biomimetic patterns that the subjects appreciated as natural touch, the subjects learned an arbitrary relationship between different sites or patterns of ICMS in S1 and the correct target.

A more complex scheme of arbitrary S1 ICMS has been used to provide Rhesus monkeys with continuous information on the direction and distance to unseen targets (Dadarlat and others 2015). Monkeys first learned to perform the task cued by a visual stimulus of moving dots. The direction and speed of the dots informed the monkey of the instantaneous direction to the target and the distance to the target, respectively. The monkeys then also received ICMS concurrently at 8 electrodes in Brodmann’s areas 1 and 2. ICMS pulses at each electrode were delivered faster to indicate greater distances to the target, and each electrode was assigned a different preferred direction without regard to the natural receptive field properties of local neurons, that is, arbitrarily. After considerable practice with both the visual and ICMS stimulation delivered concurrently, the monkeys were able to reach to the unseen targets using the S1-ICMS alone. The S1-ICMS was delivered continuously throughout each trial, and after extensive training both the initial movements and subsequent corrective submovements were made in the appropriate direction to the target. The monkeys thus learned to integrate the information delivered concurrently through eight electrodes and to use that information repeatedly (perhaps continuously) within single reaching trials. Furthermore, when the moving dots were not turned off, but their coherence was reduced (making the information they provided noisier), the monkeys could perform more accurately with both the visual and ICMS cues than with either one alone, indicating that they were able to integrate the “multisensory” natural visual and artificial, arbitrary S1-ICMS information.

Monkeys may be able to form such learned associations when ICMS is delivered in any of Brodmann’s subdivisions of S1. Discrimination of ICMS at different frequencies as instructions for different targets has been achieved in proprioceptive area 3a of a Rhesus monkey (London and others 2008). Rhesus monkeys can discriminate different ICMS frequencies accurately in area 3b (Romo and others 1998), though arbitrary learned associations of ICMS specifically in area 3b has not been reported. An owl monkey learned to detect ICMS in area 1 (O’Doherty and others 2009). Hence, targeting specific Brodmann subdivisions may not be important for purposes of arbitrary stimulation in S1.

Could ICMS in S1 ever come to be perceived as visual? This seems unlikely. Although a fraction of normal humans experience synesthesias—experiencing visual colors upon hearing particular musical passages, for example—most of us know clearly whether we are perceiving our coffee cup through touch, through vision, or through both at the same time. Those parts of the brain that receive output from S1 interpret that output as having arisen from somatosensory input, while those parts that receive output from V1 interpret that information as visual. Hence, it seems most likely that arbitrary ICMS in S1 will continue to evoke percepts that, while not entirely normal, are somatosensory in quality, while arbitrary ICMS in V1 will evoke visual percepts. Because of the difficulties in asking an animal whether a perception is somatosensory versus visual in quality, answering this question may await relevant studies in humans.

Beyond Primary Sensory Cortical Areas

Up to this point we have dealt with biomimetic or arbitrary stimulation delivered in sensory receiving areas of the cerebral cortex, a reasonable starting point given that all the information that enters the central nervous system (CNS) normally arrives through the senses. But all regions of the CNS are excitable. We therefore can ask whether information can be injected in cortical association areas beyond the sensory areas. Using surface stimulation of the human cerebral cortex exposed during surgical procedures, Penfield and his colleagues observed that stimulation in the human temporal lobe might evoke complex visual or auditory hallucinations or alterations of perceived size or distance (Penfield and Rasmussen 1950). But in large sectors of the frontal, parietal, and temporal association cortex, the patient seemed “oblivious” to stimulation unless the patient was engaged in a specific behavior involving that particular cortical region. If delivered while the patient is speaking, for example, electrical stimulation in language regions may evoke linguistic errors or frank “speech arrest” of which the patient is aware; but if not speaking, the patient may be unaware of electrical stimulation at the same location. Can artificial stimulation in such cortical association areas be used to inject information?

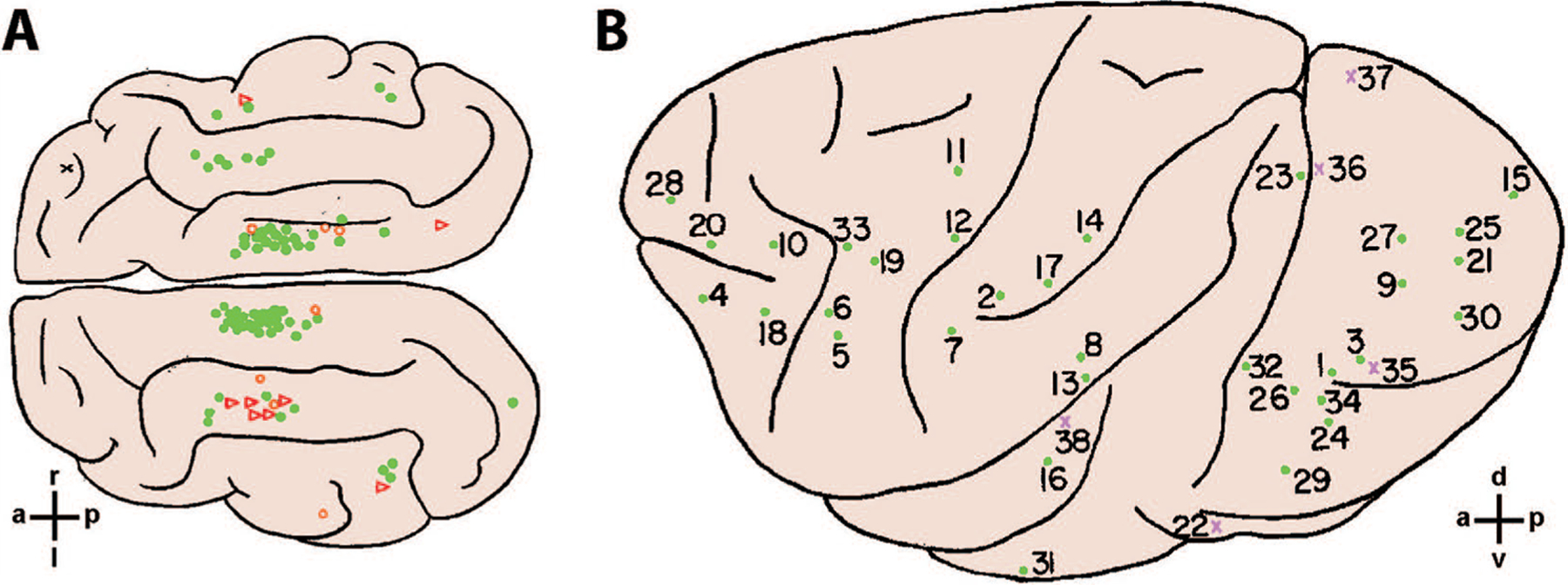

In an early study addressing this question, cats were trained to lift the right forepaw to avoid a shock if they detected electrical stimulation delivered between bipolar electrodes (2 to 4 mm apart) implanted on the surface of the cerebral cortex (Doty and others 1956). Cats could be trained successfully at most sites tested, which were largely in visual association areas (green dots in Fig. 2A). In a subsequent study, monkeys were trained initially that when a green light came on, they could press one lever to receive a food reward, whereas when a red light came on pressing a different lever prevented an aversive shock to the tail or leg (Doty 1965). The green light thus became a food-reward conditional stimulus (FRCS), whereas the red light became a shock-avoidance conditional stimulus (SACS). Electrical stimulation at one site in the cortex then was delivered simultaneously with the green light, and stimulation at another site was delivered simultaneously with the red light. After a number of such trials the green and red lights could remain off, leaving only the electrical stimulation at one site or the other as the FRCS or SACS. Monkeys still pressed the correct lever either to receive the food reward or to avoid the shock. Whereas the cats simply had detected the occurrence of electrical stimulation, the monkeys distinguished which of two cortical sites had been stimulated and responded differentially. Monkeys were trained successfully to respond to electrical stimulation at a wide variety of locations throughout the cerebral cortex, illustrated in Figure 2B. Many of these sites lay in primary or secondary visual, somatosensory, or auditory cortical areas, and the ability of the monkeys to detect and respond to stimulation at those sites might have been expected. But monkeys also were able to respond differentially to electrical stimulation at sites including premotor (sites 5, 6, 19, and 33) and prefrontal (sites 4, 20, 28) cortex, areas not involved directly in processing sensory input.

Figure 2.

Cortical locations used for arbitrary conditioning with electrical stimulation. (A) Cat. Overhead view of the feline cerebral cortex summarizing sites from 59 cats at which electrical stimulation was used as the conditional stimulus. Filled green circles indicate sites at which conditioning stimulation was successful in <400 trials; open orange circles, successful after >400 trials; and open red triangles, unsuccessful. (B) Macaque. Lateral view of the left hemisphere summarizing sites in either hemisphere from eight monkeys at which electrical stimulation at two separate sites was used for differential conditioning. Filled green circles indicate that the electrode was at or near the cortical surface; violet xs indicate that the electrode was >3 mm below the surface. Orientation crosshairs indicate: a—anterior, p—posterior, r—right, l—left, d—dorsal, v—ventral. Reproduced with permission from Doty and others (1956) (A) and Doty (1965) (B).

The locations used for the FRCS and SACS most often were separated widely (e.g., premotor vs. parietal), but in some cases monkeys distinguished stimulation between different pairs of four electrodes in a 3 mm square array in primary visual cortex (Doty 1965). Can stimulation at different electrodes in the same association area be distinguished? In a recent study, two Rhesus monkeys were trained successfully to use ICMS at different electrodes in the premotor cortex as instructions about which of four objects to reach to, grasp, and manipulate (Fig. 3; Mazurek and Schieber 2017). Prior to the introduction of ICMS, these monkeys were trained to operate the four different objects cued by four different rings of blue LEDs. Then ICMS at different electrodes was paired with each of the blue LED rings for several sessions, after which the intensity of the LEDs was gradually reduced causing the monkey’s success rates to decline and reaction times to increase. But with further reductions in LED brightness, success rates increased and reaction times decreased back to their baselines. Ultimately the LEDs could be turned off entirely and the monkeys still performed the reach-grasp-manipulate task close to 100% correct. The monkeys then could also perform well when the blue LED instructions and ICMS instructions were interleaved on different trials.

Figure 3.

Differentiating arbitrary ICMS instructions in premotor cortex. (A) Monkeys initially were trained to perform a reach, grasp, manipulate task in which blue LEDs instructed the target object. (B) ICMS in either the primary somatosensory (S1) or premotor cortex (PM) then was used to deliver instructions for performing the same task. (C) Monkey L first was trained to use S1-ICMS and subsequently was trained to use PM-ICMS. (D) Monkey X first was trained to use PM- and subsequently S1-ICMS. In each case, the monkey first performed the task using LED instructions. Beginning at session 0 (solid vertical line), ICMS was delivered through different electrodes concurrently with illumination of each of the four blue LED rings. Then, starting in the session indicated by the dotted line, the blue LEDs were dimmed progressively. Eventually the LEDs were turned off completely (dashed line), after which success rates and reaction times returned gradually to their prior baseline levels seen initially when the monkey used only LED instructions. Both monkeys thus successfully learned to use ICMS—in either S1 or PM—as instructions for performing the task. Reproduced with permission from Mazurek and Schieber (2017).

One might assume that ICMS at different sites in premotor cortex predisposed the monkeys to make different movements. But the currents used were subthreshold for evoking any muscle activity, as demonstrated by stimulus-triggered averaging of electromyographic activity. Moreover, when the assignment of the four different electrodes to the four different movements was shuffled randomly, both monkeys relearned the new assignments. These observations indicate that the monkeys differentiated four different qualia—qualities experienced, distinct from their physical source—upon stimulation at the four different electrodes, and learned to associate each of the four qualia with a different movement.

Exactly what these monkeys experienced when ICMS was delivered at different electrodes in premotor cortex remains unknown. Premotor cortex receives both processed somatosensory and visual inputs (Graziano and others 1997; Rizzolatti and others 1981a, 1981b) and contains many mirror neurons that are active when the subject observes another individual making movements of the arm and hand (di Pellegrino and others 1992; Gallese and others 1996). ICMS in the premotor cortex therefore might produce some somatosensory and/or visual qualia, or some internal representation of particular movements.

These considerations reopen the question of the extent to which subjects experience stimulation in otherwise “silent” areas of association cortex (Mazurek and Schieber 2019). Given that neurons anywhere in the CNS can be stimulated, do subjects experience some qualia no matter where stimulation is delivered? Monkeys can detect ICMS in the frontal eye field at currents subthreshold for evoking eye movement (Murphey and Maunsell 2008), but surface stimulation of the human fusiform face area often goes undetected (Murphey and others 2009). Neither an owl monkey nor a Rhesus monkey was able to learn to use ICMS in the posterior parietal cortex as an instruction about where to reach (Fitzsimmons and others 2007; O’Doherty and others 2009). Defining exactly which cortical areas can be used to inject information and which cannot will require further studies.

For such investigations, the nonverbal motor responses of trained nonhuman primates may prove as useful as the verbal responses of humans. Even in humans, not all experiences are necessarily available to the systems providing expression through language. Well known examples include the phenomenon of “blindsight,” in which a cortically blind subject can walk down a hallway avoiding obstacles while being unable to describe verbally the presence, location, or nature of the objects (de Gelder and others 2008). Similarly, subjects with visual agnosia may scale the size of their grasp aperture accurately as they reach for objects of different size without being able to verbally describe the different sizes of the objects (Goodale and Milner 1992; Goodale and others 1994). Future studies thus may show that humans can learn to use artificial stimulation at different sites without any experience they can verbalize. The ability of ICMS to induce spike-timing dependent plasticity (Guggenmos and others 2013; Jackson and others 2006; Rebesco and others 2010) may contribute to learning arbitrary associations without qualia that can be described verbally by the subject (Lebedev and Ossadtchi 2018).

Challenges for Arbitrary Stimulation

To a certain extent, arbitrary stimulation will face the same challenges as biomimetic stimulation: (1) unnaturally synchronous discharge is evoked in large numbers of neurons; (2) evoked qualia need to be integrated with normal neural activity; (3) the stimulation per se is likely to result in plastic changes in the stimulated circuits; and (4) complex spatiotemporal patterns of stimulation may be needed to provide complex information. The chief difference from biomimetic stimulation is that arbitrary stimulation outsources the solutions of these challenges to the native plasticity and learning capability of the CNS. Any plastic changes induced by artificial stimulation are unlikely to involve substantial reorganization of existing cortical representations, not only because the scale of cortical reorganization may be limited (Makin and Bensmaia 2017), but also because by definition arbitrary stimulation imposes no systematic spatial organization—for exampld, somatotopic, retinotopic, or tonotopic—on the information being delivered.

Coming up with internal solutions to these four challenges puts a larger burden (sometimes referred to as “cognitive load”) on each individual subject, requiring substantial time and effort before the artificial stimulation can be incorporated proficiently into the desired behaviors. The internal solutions may vary from subject to subject and therefore show varying degrees of success. And the rate at which information can be input arbitrarily—in terms of number of channels and bits/second in each channel—is likely to be substantially below the standard of naturally evolved sensory perception or the capacity of fully developed biomimetic stimulation. Nevertheless, in the near term, arbitrary stimulation may be more useful than biomimetic stimulation for circumstances in which our understanding of exactly what needs to be mimicked is limited.

Ethical Considerations Going Forward

Consideration of ethical issues will become increasingly important as the technology for artificially injecting various kinds of information into the nervous system improves and enters the mainstream. Injecting information raises ethical concerns somewhat different from those raised by neuroprosthetic communication devices, vision neuroprostheses, or neuroprosthetic limbs with somatosensory feedback (Bockbrader and others 2018; Loeb 2011). Like such neuroprostheses, artificial stimulation has the potential to help numerous individuals by restoring or even enhancing function. More directly than such neuroprostheses, however, injecting information—particularly arbitrary information—could provide the potential for manipulating the nervous system (Pugh and others 2018), intensifying in particular questions of the individual’s autonomy and personhood (Sample and others 2019; Yuste and others 2017).

On a daily basis, the normal nervous system takes in natural sensory and cognitive information that not only affects the individual’s choices and actions, but also is stored to extend knowledge and develop skill. This includes not only information the individual wants, needs, and intends to get but also information with which others seek to influence the individual’s actions, thoughts, and choices (e.g., targeted advertisements, social media campaigns). Artificial stimulation eventually might provide similar capabilities both to learn from and to be influenced by the incoming information stream. Major ethical issues then will have to do with maintaining the individual’s ability to differentiate information the individual intends to receive from information with which others seek to influence the individual, as well as the ability to distinguish one’s own internal thoughts from ideas introduced from outside.

Promise

Still, the ability to inject information into the cerebral cortex, and into other parts of the CNS as well, promises many opportunities for advancing both science and technology. As suggested by Doty and colleagues in the opening quotation, the ability to bypass sensory systems and inject information directly into the cerebral cortex provides new opportunities to investigate the functional capabilities of the brain. One might ask, for example, whether activity in the primary motor cortex (M1) involved in generating a particular movement differs depending on whether the instruction arrives through natural visual pathways versus through arbitrary stimulation in the premotor cortex. No difference would indicate that M1 activity generates the same movement in either case, but substantial differences in M1 activity for the same movement depending on the source of the instruction would indicate a more cognitive, context-dependent role for M1 in interpreting the inputs that lead to voluntary movement.

Injection of information into the cerebral cortex also promises to be a key functional component of neuroprosthetic devices. Visual neuroprostheses already have been developed for blind individuals, although such devices are not yet practical (Dobelle 2000; Lewis and others 2015). The recent development of robotic upper extremities controlled by neural recordings from the cortex of human participants has brought out the need for somatosensory feedback from the hand (Bensmaia and Miller 2014). Although the prosthetic arm can be moved under visual guidance, only crude grasping and manipulation of an object can be accomplished without somatosensory feedback (Wodlinger and others 2015). Current efforts to provide the requisite feedback directly into the CNS therefore focus on biomimetic stimulation in S1 (Flesher and others 2016; Hiremath and others 2017; Hughes and others 2020). Ultimately, a “bidirectional” neuroprosthetic upper extremity would both be moved under output decoded from neural activity and return feedback into the nervous system through artificial stimulation.

And beyond restoring sensory information, where biomimetic stimulation has advantages, we can envision cortico-cortical neuroprosthetic devices employing arbitrary stimulation (Averna and others 2020; Jackson and others 2006; Lebedev and Nicolelis 2017). Such a device would record neural activity from an electrode array in one cortical region, decode relevant information from the recorded activity with an on-board computer chip, and then deliver that information to a different cortical region via artificial stimulation (see Box 2). Cortico-cortical neuroprostheses could bypass injured or disordered regions of cortex and thereby contribute to restoring a wide variety of higher cortical functions.

Box 2. Cortico-cortical Neuroprostheses to Restore Higher Cortical Functions.

Work employing artificial stimulation to inject information into the nervous system has focused primarily on restoring sensory inputs, including somatosensory feedback to help control a prosthetic limb, visual prostheses, and the cochlear implant. However, technological advances in neural recording and stimulating arrays, progressive miniaturization of computer chips, and increasingly sophisticated computational neural models have provided the building blocks for realizing a rehabilitative system that could restore information along CNS pathways damaged by a focal neurologic injury. Cortical areas communicate information with one another to accomplish particular functions. For example (A), neural information (curved arrows) from visual cortex (V) about object shape and location normally is processed in the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) and communicated to the premotor cortex (PM) to plan reaching and grasping controlled by the primary motor cortex (M1).

A focal neurologic injury along this pathway (B, red X) would disrupt communication between V and PM, and impair reaching and grasping. Neural recordings made in visual cortex (violet electrode grid) then could be decoded by an implanted computer chip (square), and the necessary information could be injected directly into PM (yellow lightning bolt). Such a cortico-cortical prosthesis (lower right-angled arrow) would effectively bypass the lesion and restore neural function that the patient could learn to use. Similar prostheses could be applied to any number of CNS pathways where connectivity might be disrupted by different injuries, restoring function for a large number of patients in whom such a rehabilitative solution might improve quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks Marsha Hayles for editorial comments.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Grants F32NS093709 to KAM and R01NS107271 to MHS from the NINDS.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Andersen P, Hagan PJ, Phillips CG, Powell TP. 1975. Mapping by microstimulation of overlapping projections from area 4 to motor units of the baboon’s hand. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 188(1090):31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma H, Rosen I. 1972. Topographical organization of cortical efferent zones projecting to distal forelimb muscles in the monkey. Exp Brain Res 14(3):243–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma H, Ward JE. 1971. Patterns of contraction of distal forelimb muscles produced by intracortical stimulation in cats. Brain Res 27(1):97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averna A, Pasquale V, Murphy MD, Rogantin MP, Van Acker GM, Nudo RJ, and others. 2020. Differential effects of open- and closed-loop intracortical microstimulation on firing patterns of neurons in distant cortical areas. Cereb Cortex 30(5):2879–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach-y-Rita P 2004. Tactile sensory substitution studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1013:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak M, Girvin JP, Hambrecht FT, Kufta CV, Loeb GE, Schmidt EM. 1990. Visual sensations produced by intracortical microstimulation of the human occipital cortex. Med Biol Eng Comput 28(3):257–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensmaia SJ, Miller LE. 2014. Restoring sensorimotor function through intracortical interfaces: progress and looming challenges. Nat Rev Neurosci 15(5):313–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi G, Poo M. 2001. Synaptic modification by correlated activity: Hebb’s postulate revisited. Annu Rev Neurosci 24:139–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockbrader MA, Francisco G, Lee R, Olson J, Solinsky R, Boninger ML. 2018. Brain computer interfaces in rehabilitation medicine. PM R 10(9 suppl 2):S233–S243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosking WH, Beauchamp MS, Yoshor D. 2017. Electrical stimulation of visual cortex: relevance for the development of visual cortical prosthetics. Annu Rev Vis Sci 3:141–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovas S, Schwarz C. 2003. Spatiotemporal effects of microstimulation in rat neocortex: a parametric study using multielectrode recordings. J Neurophysiol 90(5):3024–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G, Wang XJ. 2012. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations. Annu Rev Neurosci 35:203–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callier T, Brantly NW, Caravelli A, Bensmaia SJ. 2020. The frequency of cortical microstimulation shapes artificial touch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117(2):1191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Alamancos MA, Connors BW. 1996. Short-term synaptic enhancement and long-term potentiation in neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93(3):1335–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvette S, Soltani S, Seigneur J, Timofeev I. 2016. In vivo models of cortical acquired epilepsy. J Neurosci Methods 260:185–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing H 1909. A note upon the faradic stimulation of the postcentral gyrus in conscious patients. Brain 32:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dadarlat MC, O’Doherty JE, Sabes PN. 2015. A learning-based approach to artificial sensory feedback leads to optimal integration. Nat Neurosci 18(1):138–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gelder B, Tamietto M, van Boxtel G, Goebel R, Sahraie A, van den Stock J, and others. 2008. Intact navigation skills after bilateral loss of striate cortex. Curr Biol 18(24):R1128–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deadwyler SA, Hampson RE, Song D, Opris I, Gerhardt GA, Marmarelis VZ, and others. 2017. A cognitive prosthesis for memory facilitation by closed-loop functional ensemble stimulation of hippocampal neurons in primate brain. Exp Neurol 287(Pt 4):452–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K 2015. Optogenetics: 10 years of microbial opsins in neuroscience. Nat Neurosci 18(9):1213–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C, Yuan H, Dai J. 2018. Behavioral manipulation by optogenetics in the nonhuman primate. Neuroscientist 24(5):526–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Pellegrino G, Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Gallese V, Rizzolatti G. 1992. Understanding motor events: a neurophysiological study. Exp Brain Res 91(1):176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobelle WH. 2000. Artificial vision for the blind by connecting a television camera to the visual cortex. ASAIO J 46(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RW. 1965. Conditioned reflexes elicited by electrical stimulation of the brain in macaques. J Neurophysiol 28:623–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RW, Larsen RM, Ruthledge LT Jr., 1956. Conditioned reflexes established to electrical stimulation of cat cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol 19(5):401–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons NA, Drake W, Hanson TL, Lebedev MA, Nicolelis MA. 2007. Primate reaching cued by multichannel spatiotemporal cortical microstimulation. J Neurosci 27(21):5593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesher SN, Collinger JL, Foldes ST, Weiss JM, Downey JE, Tyler-Kabara EC, and others. 2016. Intracortical microstimulation of human somatosensory cortex. Sci Transl Med 8(361):361ra141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch G, Hitzig E. 1870. Über die elektrische Erregbarkeit des Grosshirn [On the electrical excitability of the cerebrum]. Archive für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin: 300–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V, Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Rizzolatti G. 1996. Action recognition in the premotor cortex. Brain 119(2):593–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A, Stauffer WR, Acker L, El-Shamayleh Y, Inoue KI, Ohayon S, and others. 2017. Nonhuman primate optogenetics: recent advances and future directions. J Neurosci 37(45):10894–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodale MA, Jakobson LS, Keillor JM. 1994. Differences in the visual control of pantomimed and natural grasping movements. Neuropsychologia 32(10):1159–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodale MA, Milner AD. 1992. Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends Neurosci 15(1):20–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano MSA, Hu XTA, Gross CG. 1997. Visuospatial properties of ventral premotor cortex. J Neurophysiol 77(5):2268–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggenmos DJ, Azin M, Barbay S, Mahnken JD, Dunham C, Mohseni P, and others. 2013. Restoration of function after brain damage using a neural prosthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110(52):21177–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson RE, Song D, Robinson BS, Fetterhoff D, Dakos AS, Roeder BM, and others. 2018. Developing a hippocampal neural prosthetic to facilitate human memory encoding and recall. J Neural Eng 15(3):036014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess G, Donoghue JP. 1999. Facilitation of long-term potentiation in layer II/III horizontal connections of rat motor cortex following layer I stimulation: route of effect and cholinergic contributions. Exp Brain Res 127(3):279–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiremath SV, Tyler-Kabara EC, Wheeler JJ, Moran DW, Gaunt RA, Collinger JL, and others. 2017. Human perception of electrical stimulation on the surface of somatosensory cortex. PLoS One 12(5):e0176020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Histed MH, Bonin V, Reid RC. 2009. Direct activation of sparse, distributed populations of cortical neurons by electrical microstimulation. Neuron 63(4):508–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D, Petreanu L, Ghitani N, Ranade S, Hromadka T, Mainen Z, and others. 2008. Sparse optical microstimulation in barrel cortex drives learned behaviour in freely moving mice. Nature 451(7174):61–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, Herrera A, Gaunt R, Collinger J. 2020. Bidirectional brain-computer interfaces. Handb Clin Neurol 168:163–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussin AT, Boychuk JA, Brown AR, Pittman QJ, Teskey GC. 2015. Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) activates motor cortex layer 5 pyramidal neurons mainly transsynaptically. Brain Stimul 8(4):742–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriki A, Pavlides C, Keller A, Asanuma H. 1989. Long-term potentiation in the motor cortex. Science 245(4924):1385–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, Mavoori J, Fetz EE. 2006. Long-term motor cortex plasticity induced by an electronic neural implant. Nature. 444(7115):56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki F, Constantinidis C. 2014. Bottom-up and top-down attention: different processes and overlapping neural systems. Neuroscientist 20(5):509–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa H, Nishimura Y, Yoshioka K, Lin M, Yamamoto T. 1997. Long-term potentiation and depression in layer III and V pyramidal neurons of the cat sensorimotor cortex in vitro. Brain Res 751(2):339–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedev MA, Nicolelis MA. 2017. Brain-machine interfaces: from basic science to neuroprostheses and neurorehabilitation. Physiol Rev 97(2):767–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedev MA, Ossadtchi A. 2018. Commentary: injecting instructions into premotor cortex. Front Cell Neurosci 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis PM, Ackland HM, Lowery AJ, Rosenfeld JV. 2015. Restoration of vision in blind individuals using bionic devices: A review with a focus on cortical visual prostheses. Brain Res 1595:51–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb GE. 2011. Neuroprosthetic interfaces—the reality behind bionics and cyborgs. In: Schleidgen S, Jungert M, Bauer R, Sandow V editors. Human nature and self design. Mentis. p. 163–76. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb GE. 2018. Neural prosthetics: a review of empirical vs. systems engineering strategies. Appl Bionics Biomech 2018:1435030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London BM, Jordan LR, Jackson CR, Miller LE. 2008. Electrical stimulation of the proprioceptive cortex (area 3a) used to instruct a behaving monkey. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 16(1):32–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier MA, Kirkwood PA, Brochier T, Lemon RN. 2013. Responses of single corticospinal neurons to intracortical stimulation of primary motor and premotor cortex in the anesthetized macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol 109(12):2982–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makin TR, Bensmaia SJ. 2017. Stability of sensory topographies in adult cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 21(3):195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshel JH, Kim YS, Machado TA, Quirin S, Benson B, Kadmon J, and others. 2019. Cortical layer-specific critical dynamics triggering perception. Science 365(6453):eaaw4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May T, Ozden I, Brush B, Borton D, Wagner F, Agha N, and others. 2014. Detection of optogenetic stimulation in somatosensory cortex by non-human primates—towards artificial tactile sensation. PLoS One 9(12):e114529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek KA, Schieber MH. 2017. Injecting instructions into premotor cortex. Neuron 96(6):1282–89.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek KA, Schieber MH. 2019. How is electrical stimulation of the brain experienced, and how can we tell? Selected considerations on sensorimotor function and speech. Cogn Neuropsychol 36(3–4):103–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphey DK, Maunsell JH. 2008. Electrical microstimulation thresholds for behavioral detection and saccades in monkey frontal eye fields. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105(20):7315–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphey DK, Maunsell JH, Beauchamp MS, Yoshor D. 2009. Perceiving electrical stimulation of identified human visual areas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(13):5389–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najarpour Foroushani A, Pack CC, Sawan M. 2018. Cortical visual prostheses: from microstimulation to functional percept. J Neural Eng 15(2):021005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni AM, Maunsell JH. 2010. Microstimulation reveals limits in detecting different signals from a local cortical region. Curr Biol 20(9):824–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll RA. 2017. A brief history of long-term potentiation. Neuron 93(2):281–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y, Perlmutter SI, Eaton RW, Fetz EE. 2013. Spike-timing-dependent plasticity in primate corticospinal connections induced during free behavior. Neuron 80(5):1301–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak LG, Bullier J. 1998a. Axons, but not cell bodies, are activated by electrical stimulation in cortical gray matter I. Evidence from chronaxie measurements. Exp Brain Res 118(4):477–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak LG, Bullier J. 1998b. Axons, but not cell bodies, are activated by electrical stimulation in cortical gray matter II. Evidence from selective inactivation of cell bodies and axon initial segments. Exp Brain Res 118(4):489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JE, Lebedev MA, Hanson TL, Fitzsimmons NA, Nicolelis MA. 2009. A brain-machine interface instructed by direct intracortical microstimulation. Front Integr Neurosci 3:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JE, Lebedev MA, Ifft PJ, Zhuang KZ, Shokur S, Bleuler H, and others. 2011. Active tactile exploration using a brain-machine-brain interface. Nature 479(7372):228–U106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JE, Shokur S, Medina LE, Lebedev MA, Nicolelis MAL. 2019. Creating a neuroprosthesis for active tactile exploration of textures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116(43):21821–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds J, Milner P. 1954. Positive reinforcement produced by electrical stimulation of septal area and other regions of rat brain. J Comp Physiol Psychol 47(6):419–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet CK, Hellman RB, Ponce Wong RD, Santos VJ, Helms Tillery SI. 2016. Discriminability of single and multichannel intracortical microstimulation within somatosensory cortex. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 4:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Boldrey E. 1937. Somatic motor and sensory representation in the cerebral cortex of man as studied by electrical stimulation. Brain 37:389–443. [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Rasmussen T. 1950. The cerebral cortex of man. MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Pinar C, Fontaine CJ, Trivino-Paredes J, Lottenberg CP, Gil-Mohapel J, Christie BR. 2017. Revisiting the flip side: long-term depression of synaptic efficacy in the hippocampus. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 80:394–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons TP, Garraghty PE, Ommaya AK, Kaas JH, Taub E, Mishkin M. 1991. Massive cortical reorganization after sensory deafferentation in adult macaques. Science 252(5014):1857–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh J, Pycroft L, Sandberg A, Aziz T, Savulescu J. 2018. Brainjacking in deep brain stimulation and autonomy. Ethics Inf Technol 20(3):219–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranck JB. 1975. Which elements are excited in electrical-stimulation of mammalian central nervous-system—review. Brain Res 98(3):417–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebesco JM, Miller LE. 2011. Stimulus-driven changes in sensorimotor behavior and neuronal functional connectivity application to brain-machine interfaces and neurorehabilitation. Prog Brain Res 192:83–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebesco JM, Stevenson IH, Kording KP, Solla SA, Miller LE. 2010. Rewiring neural interactions by micro-stimulation. Front Syst Neurosci 4:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Scandolara C, Matelli M, Gentilucci M. 1981a. Afferent properties of periarcuate neurons in macaque monkeys. I. Somatosensory responses. Behav Brain Res 2(2):125–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Scandolara C, Matelli M, Gentilucci M. 1981b. Afferent properties of periarcuate neurons in macaque monkeys. II. Visual responses. Behav Brain Res 2(2):147–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romo R, Hernandez A, Zainos A, Salinas E. 1998. Somatosensory discrimination based on cortical microstimulation. Nature 392(6674):387–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux FE, Djidjeli I, Durand JB. 2018. Functional architecture of the somatosensory homunculus detected by electrostimulation. J Physiol 596(5):941–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sample M, Aunos M, Blain-Moraes S, Bublitz C, Chandler JA, Falk TH, and others. 2019. Brain-computer interfaces and personhood: interdisciplinary deliberations on neural technology. J Neural Eng 16(6):063001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt EM, Bak MJ, Hambrecht FT, Kufta CV, O’Rourke DK, Vallabhanath P. 1996. Feasibility of a visual prosthesis for the blind based on intracortical microstimulation of the visual cortex. Brain. 119(Pt 2):507–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM. 2016. Thalamus plays a central role in ongoing cortical functioning. Nat Neurosci 19(4):533–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoney SD Jr, Thompson WD, Asanuma H 1968. Excitation of pyramidal tract cells by intracortical microstimulation: effective extent of stimulating current. J Neurophysiol 31(5):659–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Huang S, Wang N. 2019. Neural interface: frontiers and applications: cochlear implants. Adv Exp Med Biol 1101:167–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swadlow HA, Beloozerova IN, Sirota MG. 1998. Sharp, local synchrony among putative feed-forward inhibitory interneurons of rabbit somatosensory cortex. J Neurophysiol 79(2): 567–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabot GA, Dammann JF, Berg JA, Tenore FV, Boback JL, Vogelstein RJ, and others. 2013. Restoring the sense of touch with a prosthetic hand through a brain interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110(45):18279–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar SK, Xu S, Hawley ES, Weiss SA, Moxon KA, Chapin JK. 2002. Rat navigation guided by remote control. Nature 417(6884):37–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Nomoto T, Shiki T, Sakata Y, Shimada Y, Hayashida Y, and others. 2019. Focal activation of neuronal circuits induced by microstimulation in the visual cortex. J Neural Eng 16(3):036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehovnik EJ. 1996. Electrical stimulation of neural tissue to evoke behavioral responses. J Neurosci Methods 65(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehovnik EJ, Slocum WM. 2013. Electrical induction of vision. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37(5):803–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehovnik EJ, Slocum WM, Smirnakis SM, Tolias AS. 2009. Microstimulation of visual cortex to restore vision. Neurother Prog Restor Neurosci Neurol 175:347–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teskey GC, Young NA, van Rooyen F, Larson SE, Flynn C, Monfils MH, and others. 2007. Induction of neocortical long-term depression results in smaller movement representations, fewer excitatory perforated synapses, and more inhibitory synapses. Cereb Cortex 17(2): 434–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troyk P, Bak M, Berg J, Bradley D, Cogan S, Erickson R, and others. 2003. A model for intracortical visual prosthesis research. Artif Organs 27(11):1005–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsu AP, Burish MJ, GodLove J, Ganguly K. 2015. Cortical neuroprosthetics from a clinical perspective. Neurobiol Dis 83:154–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winawer J, Parvizi J. 2016. Linking electrical stimulation of human primary visual cortex, size of affected cortical area, neuronal responses, and subjective experience. Neuron 92(6):1213–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodlinger B, Downey JE, Tyler-Kabara EC, Schwartz AB, Boninger ML, Collinger JL. 2015. Ten-dimensional anthropomorphic arm control in a human brain-machine interface: difficulties, solutions, and limitations. J Neural Eng 12(1):016011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtz RH. 2008. Neuronal mechanisms of visual stability. Vision Res 48(20):2070–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R, Goering S, Arcas BAY, Bi G, Carmena JM, Carter A, and others. 2017. Four ethical priorities for neurotechnologies and AI. Nature 551(7679):159–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]