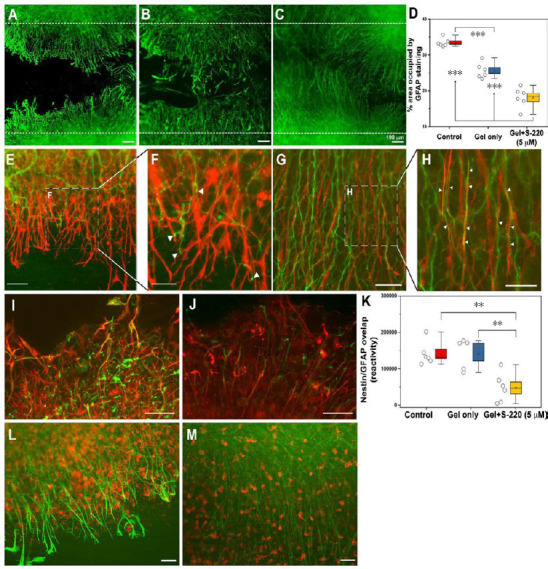

Figure 8.

S-220 incorporated into the hydrogel promotes neurite outgrowth and suppresses astrocyte activation.

(A–D) Representative images exhibit astrocyte activation in the lesion using GFAP staining as an astrocyte marker. (A) Control. (B) Gel only. (C) Gel + 5 µM S-220. (D) Quantification of the GFAP immunoreactivity intensity showed a significant reduction of mean grey value (OD) in gel + 5 µM S-220 compared to the control and the gel only treatment. E, Representative image of the relationship between GFAP, (red) and β-tubulin-III (green) immunoreactive processes in a control injury condition. (F) Higher magnification image showing the collapse of growth cones (white arrowheads) when they meet activated astrocytes. (G) Representative image of the relationship between GFAP and β-tubulin-III immunoreactive processes in a lesion with combined treatment with gel + 5 µM S-220. (H) Higher magnification image showing the alignment of the astrocytes and β-tubulin-III immunoreactive processes (white arrowheads). (I–K) Levels of astrocyte reactivity were estimated by the overlapping of GFAP (red) and nestin (green). (I) Representative image of GFAP/nestin reactivity in lesion sites of non-treated slices. (J) Representative image of GFAP/nestin overlapping in slices treated with S-220 delivered by the hydrogel. (K) Quantification of GFAP/nestin pixel overlapping. (L) Representative image of the relationship between GFAP and Iba-1 immunoreactive cells in an injured control. (M) Representative image of the relationship between GFAP and Iba-1 immunoreactive cells in injured slices treated with a combination of hydrogel + 5 µM S-220. Circles represent individual biological replicates (n= 4–6). Scale bars: A–C, I and J, 100 µm; E and G, 50 µm; F and H, 25 µm; L and M, 50 µm. GFAP: Glial fibrillang acidic protein. Adapted from Guijarro-Belmar et al. (2019).