Graphical abstract

Keywords: Agile development, Respirator, Product development, Rapid prototyping, COVID-19, Nimble manufacturing

Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic presented European hospitals with chronic shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as surgical masks and respirator masks. Demand outstripped the production capacity of certified European manufacturers of these devices. Hospitals perceived emergency local manufacturing of PPE as an approach to reduce dependence on foreign supply. The fact of a pandemic does not circumvent the hospital’s responsibility to provide appropriate protective equipment to their staff, so the emergency production needed to result in devices that were certified by testing agencies. This paper is a case study of the emergency manufacturing of respirator masks during the first month of the first wave of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and is separated into two distinct phases. Phase A describes the three-panel folding facepiece respirator design, material sourcing, performance testing, and an analysis of the folding facepiece respirator assembly process. Phase B describes the redevelopment of individual steps in the assembly process

1. Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (“COVID-19 pandemic”) requires personal protection precautions to be taken. These precautions are taken to firstly create a barrier against body fluids transmission between patients and health workers, and secondly as anti-viral respiratory protection for the health workers (through filtration). Mouth masks are one of the key products used as part of these precautionary measures. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a worldwide scarcity of both surgical masks and filtering facepiece respirators (“FFRs”).

1.1. Background to the case study

On 6 March 2020, Antwerp’s University Hospital (“UZA”) identified an impending FFR supply shortage for its staff and patients due to the COVID-19 pandemic and requested help from the University of Antwerp’s Department of Product Development. A small team of doctoral candidates and professors within this Department (“Antwerp Design Factory”) assembled to tackle this impending FFR shortage, caused by a surge in COVID-19 infections in the Antwerp region. The key personal protective equipment (“PPE”) used by European hospitals are FFP2 and FFP3 respirators. From early 2020 it became challenging for hospitals to acquire adequate stock due to a surge in global demand, panic buying by the wider public, depleted strategic stocks, unstable wholesale markets, the unreliable quality of imported masks, disruption of the supply chain and other consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, UZA consumed around 16000 valveless FFP2 respirators. From March 2020, this leapt up by approximately ten-fold to a consumption rate of 450 FFP2 respirators per day. UZA initially requested that the Antwerp Design Factory produces between 150–300 FFP2 or FFP3 respirators per week, to help ease pressure in their supply chain. To address UZA’s needs, the Antwerp Design Factory set out to design a fully functional, comfortable and certifiable FFR, that could be produced locally with available materials and infrastructure as quickly as possible.

1.2. Agile compared to the traditional product development methodology

A product development process usually consists out of sequential steps that convert a set of inputs into a set of outputs. This process is used by companies to conceive, design and commercialize a product. A well-defined process will lead to quality assurance, coordination, planning, management and improvement. The generic product development process is comprised of six phases with several defined key activities and responsibilities of the functions of the organizations [1]. Ulrich and Eppinger identified the following six phases as: planning, concept development, system-level design, detail design, testing and refinement and production ramp-up.

This process has the structure of a waterfall model. It is broken down into linear, sequential stages, and each section is dependent upon the deliverables of the previous stage. Once a new stage has started, it is not possible to retreat to a previous stage. This design method does not allow for much flexibility or changes during the process. These traditional development process models are based on the idea that system requirements can be fully known at the outset. However, when there are vague or inadequate requirements, up-front planning appears irrational. It is common to have vague requirements at the start of a development process [2].

The traditional model is hard to apply during a crisis. This is because it is a slow and non-flexible model which is hard to implement with vague requirements and when the design specifications can change at any moment. When development speed and flexibility are crucial for a successful outcome, agile development appears to be a more useful process [3].

Agile development is a process that originates from the software development world [4]. It is an iterative, time-based, and result-oriented process, first introduced by Schwaber, K. in 1997. “Agile software development indicates software development methodologies based on the concept of iterative development, which creates requirements and solutions through cooperation among self-organized cross-functional teams.” [5] One of the most commonly used design frameworks within the agile process is SCRUM. The SCRUM framework was developed in the early 1990s by K. Schwaber & J. Sutherland [6]. It is a lightweight framework that helps people, teams and organizations to generate value through adaptive solutions for complex problems. The agile development manifesto is made up of twelve principles that were described in 2001 by Beck et al. [7].

Agile development was initially designed for software development, but it has also been applied in the product development context [7]. The differences between agile development for software and hardware systems was studied by Stelzmann [8]. Stelzmann analyzed existing work about agile software development and conducted interviews in systems development companies. He concluded that “in contrast to software, hardware systems that have to be produced physically often are difficult to be developed in small cyclic steps”. He also stated that “Only if prototyping, testing, and implementing changes can be done quickly and cheaply, this principle is feasible’”.

Since the expiration of several key patents in additive manufacturing in 2010s, the prototyping industry has boomed and continues to grow exponentially [9]. Rapid prototyping continues to become cheaper and more accessible. This means that modern product development can overcome Stelzmann’s concerns. It is therefore possible to apply agile development guidelines to the product development context.

According to Vinodh et al., product development flexibility is among one of four major key factors enabling supply chain agility, crucial in adapting to a rapidly changing global competitive environment. The other factors are sourcing flexibility, manufacturing flexibility and logistics flexibility [10].

1.3. Agile development applied during crises

Natural and man-made disasters may occur at any time and are likely to occur more frequently due to climate change and environmental degradation [11]. In times of emergency, agile manufacturing and agile development have an important role to play to help society manage the consequences of natural and man-made disasters. An example of agile manufacturing and agile development can be found in 2005′s Hurricane Katrina system that affected North America. At that time, Walmart and other large private enterprises wanted to protect their own physical assets. These large corporations therefore created their own in-house departments to plan for their recovery and response to natural disasters [3]. Walmart used agile manufacturing and development processes in their disaster planning and management. The easily expendable structure of Walmart's emergency response protocols “drives the ability to be agile and flexible” [12]. Walmart received universal praise for the way it responded to Hurricane Katrina [13]. In contrast, the United States federal government was far less effective at dealing with the natural disaster due to a lack of agility and resilience in its processes and applications. Many commentators have concluded that governments could learn from the agile processes applied by private corporations in order to prevent future failings in future disaster situations [14].

For manufacturing processes to be able to adapt during times of crisis they need to be smart and resilient. Linear waterfall processes have proven to fail when circumstances are uncertain and prone to change. In contrast, an agile process can help manufacturing processes to be flexible to changes during production. Some production techniques are better suited than others to cope with changing requirements. Additive manufacturing is a good example of a smart, agile process [15]. It can be used for small scale production where flexibility and lead time are a higher priority than production costs. These techniques are ideal if the process is prone to changes. Whenever certain requirements are set, the process can shift to more traditional manufacturing methods such as injection molding. Some other examples of agile manufacturing processes are laser cutting [16] and CNC-milling [17]. Many nimble manufacturing methods proved to be resourceful for immediate, local response to combat the corona virus. As shown by an in-depth case study [18], several global efforts were established to mass produce ventilators, nasopharyngeal swabs and PPE such as face masks and face shields [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23]]. By using additive manufacturing, they were able to immediately meet urgent demand while overcoming challenges within the supply chain.

1.4. Up front prototyping

Up-front prototyping describes a shift in how prototyping is used during the design process. In traditional design, prototyping is used only as a validation tool to evaluate the final design that has already been thoroughly analyzed [24]. Up-front prototyping describes a method where prototypes are made throughout several stages of the design process before complete analysis of the design. These prototypes can be used to test the design or its sub-systems by trial-and-error or at more regular intervals compared to traditional development processes. Up-front prototyping is only possible because of the lower price and higher speed of modern prototyping methods. This allows frequent reiteration of the prototype in a short period of time to improve the quality of the design. This cycle can be rapidly repeated many times until the final requirements are satisfied.

The agile development cycle in a manufacturing context, described by Stelzmann, consists of four stages: (1) observe, (2) analyze, (3) develop/build and (4) test/demonstrate. These steps form a circular feedback loop of the testing and demonstration results being fed into a re-observation phase, which then couples with inputs that are external to the development task.

This article uses this emergency production of filtering facepiece respirators as case study for agile product development. The four agile development stages were cyclically applied during the development process, with each cycle taking longer and becoming more detailed until a final design was crystallized.

2. Regulatory requirements

When developing emergency FFRs under pandemic conditions, it is important to understand the regulatory requirements that apply to this class of PPE”. It is also important to note that regulations, guidance and testing of FFRs changed rapidly during March and April 2020 both at a European Union level and at the individual member state level. Further, many individual EU member states acted unilaterally to set their own regulatory requirements that would apply to PPE. This section discusses the existing regulations that were in place at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the subsequent assessments and recommendations that were made by the European Commission in response to the pandemic, and subsequent changes made at the Belgian level for the testing and accreditation of FFRs.

In Europe, FFRs are regulated by Regulation (EU) 2016/425 of the European Parliament and of the European Council of 9 March 2016 on personal protective equipment and repealing Council Direction 89/686/EEC [25]. This regulation requires manufacturers of filtering facepiece respirators to conform with the EN149:2001 + A1:2009 standard, and to place CE marking on the respirator mask to indicate to users that the masks conforms with the required standard. Belgian hospitals are required to provide PPE to staff that adheres to Regulation (EU) 2016/425 [25]. Under the EN149:2001 + A1:2009 standard, there are three defined levels of respiratory protection, namely FFP1, FFP2 and FFP3, where FFP refers to a filtering facepiece. Table 1 shows the minimum allowable filter material penetration and total inward leakage (TIL) of respirators that adhere to the EN149:2001 + A1:2009 standard. FFP2 (>94 %) and FFP3 (>99 %) respirators are broadly similar to the masks certified under standard 42 CFR 84 from the United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) for N95 and N99 filtering facepieces, respectively. The names of all clauses and tests undertaken in the EN149:2001+A1:2009 standard is shown in Table 2 .

Table 1.

Minimum allowable filter penetration and total inward leakage of respirator masks as certified under the EN149:2001 + A1:2009 standard.

| Class | Filter penetration limit (at 95 L/min air flow) | Total inward leakage |

|---|---|---|

| FFP1 | Filters at least 80 % of airborne particles | <22 % |

| FFP2 | Filters at least 94 % of airborne particles | <8% |

| FFP3 | Filters at least 99 % of airborne particles | <2% |

Table 2.

Comparison of alternative European emergency EN149 certifications including EN149 clause, CPA, Czech simplified EN149, EN149 test, and ATP protocol.

| Test property | EN149 clause | German pandemic certification (CPA) | Czech pandemic certification (simplified EN140) | EN149 test | Belgian ATP protocol (simplified EN149) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | 7.1 | ||||

| Nominal values and tolerances | 7.2 | ||||

| Visual inspection | 7.3 | x | x | ||

| Packaging | 7.4 | x | |||

| Material | 7.5 | 8.2 | |||

| Cleaning and disinfecting | 7.6 | ||||

| Practical performance | 7.7 | x | 8.4 | x | |

| Finish of parts | 7.8 | ||||

| Total inward leakage | 7.9.1 | x | x | 8.5 | x |

| Penetration of filter material | 7.9.2 | x | x | 8.11 | |

| Compatibility with skin | 7.10 | 8.4, 8.5 | |||

| Flammability | 7.11 | 8.6 | |||

| Carbon dioxide content of inhalation air | 7.12 | x | 8.7 | ||

| Head harness | 7.13 | 8.4, 8.5 | |||

| Field of vision | 7.14 | 8.4 | |||

| Exhalation valve(s) | 7.15 | x | 8.2, 8.3, 8.5, 8.8 | ||

| Breathing resistance | 7.16 | x | x | 8.9 | |

| Clogging | 7.17 | 8.10 |

Due to the unprecedented pressure in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic on the supply of European-certified respiratory protective equipment, the European Commission published Recommendation (EU) 2020/403 of 13 March 2020 on conformity assessment and market surveillance procedures with the context of the COVID-19 threat [26]. The recommendation offered two important strategies to member states and, by extension, to their hospitals. Firstly, it allowed the importation of FFRs which had been certified in non-European regulatory environments. The Belgian federal government provided guidance that allowed the importation of certified FFRs from Australia, Brazil, China, Korea, Japan, Mexico and the USA [27]. Importantly, this included FFRs manufactured under the Chinese standard GB2626−2006, which under the circumstances was deemed equivalent to the European standard EN149:2001 + A1:2009. Secondly, EU member states’ notified bodies could issue certificates for PPE products that were manufactured following technical solutions other than the accepted harmonized standards, so long as these masks were only provided to hospital workers.

An early success was from a notified body in the Czech Republic, the Occupational Safety Research Institute (VUBP), that performed simplified pandemic certification tests for the EN140:1998 standard for half masks and quarter masks. This certification was utilized by a research group from the Czech Institute of Informatics, Robotics and Cybernetics (CIIRC) to validate a half mask respirator design that was manufactured using a HP MultiJet Fusion 3D printing platform [28]. The tests performed in the Czech pandemic certification are shown in Table 2, alongside the tests for EN149:2001+A1:2009, which in this case is relevant because the performance requirements of these tests are equivalent for both the EN140 and EN149. The Czech pandemic certificate for the EN140:1998 was issued for the CIIRC respirator on 20 March 2020 and demonstrated the resilience of notified bodies in individual member states to quickly react to guidance from the European level. However, this certificate is only valid in the Czech Republic.

Another early mover in Europe was the German Central Office of the States for Safety Technology (“ZLS”). The ZLS asked two leading German notified bodies in the field of respiratory protective equipment, the German Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (IFA) and DEKRA Industrial, to develop a simplified version of the EN149:2001 + A1:2009. This simplified standard was named “Corona SARS-CoV-2 pandemic respiratory protection” or CPA (from the German, Corona-Pandemieatemschutz) [29]. This simplified standard reduced the number of tests that a new respirator mask would have to undergo from the full 18 clauses in the EN149:2001 + A1:2009 down to only 7 clauses for the CPA. The tests undertaken in the CPA are indicated in Table 2, alongside the EN149 and Czech pandemic EN140 tests. Filtering facepiece respirators certified through the CPA protocol would again only be valid in Germany. However, after 27 March 2020, the CPA initiative was more widely adopted among European notified bodies for PPE, after recommendations for use of the CPA protocol were published in the European Commission Recommendations for the Co-ordination of Notified Bodies (PPE-R/02.075 Version 1) regarding PPE Regulation 2016/425 [25].

An unintended consequence of the European Commission’s recommendation on market surveillance which allowed the importation of Chinese KN95 respirator masks as equivalent to the FFP2, was that many fraudulently-marked, poorly-filtering or poorly-fitting KN95 respirator masks were imported into Belgium and other European countries. An emergency testing protocol was therefore urgently required in Belgium to the evaluate the performance of the imported KN95 respirators. The Belgian Federal government established alternative testing protocol (ATP) procedures for both FFP-style masks [30] and surgical masks [31].The Belgian ATP for respirator mask was a simplified test protocol for FFP2/FFP3-masks. Only three clauses from the EN149:2001+A1:2009 standard were included. These are shown in Table 2 with the other certifications that were available at that time. Only two criteria were tested, and relied heavily on the use of QNFT using a Portacount 8038 (TSI Inc.) for the evaluation:

-

•

The maximum allowed values for penetration of the filter medium (“Penetration of filter medium”, PFM). This value is used to describe the permeability of the fabric, used in the mask. This was typically performed by taping the respirator mask to the face of the user. In this way, the mask would be completely sealed from facial leakage, and therefore any failure to reach a “pass” level for a QNFT was due to poor material.

-

•

The maximum allowed inward leakage (“Total Inward Leakage”, TIL). This value is used to describe how well the face is sealed by the mask. A standard QNFT was performed using a Portacount 8038 (TSI Inc.) in the N95 companion mode to evaluate face fitting and from this calculating the TIL.

Depending on the results of the tests, the FFP2- and FFP3 face masks were allocated into four different categories: Okay to Use, Not Okay to Use, Tape Nose and Tape All. Advice was then provided to Belgian hospitals on how to safely use respirators produced by different manufacturers. They were given the advice to either not use the mask at all, tape the nose section, tape around the whole border of the mask, or use it normally. A list of respirators that had been tested via the ATP procedure is detailed on the website of the Belgian Federal Public Service Economy, specifying in particular those masks that did not receive an “Okay to Use” evaluation. At the time of writing, around 200 different brands of respirators were listed as unsuitable for normal use in hospitals.

The Antwerp Design Factory’s final regulatory testing strategy was to send the team’s FFRs to IFA in Germany for the CPA testing. In addition, the FFRs would be sent for testing under the Belgian ATP procedure.

3. Sprint to the minimum viable product and upscaling production

The development process can be split in two phases: Phase A and Phase B. In Phase A, an agile development methodology is used to create a certified, working mask design in the shortest amount of time possible. During this process, many iterations were tested until a working design was completed: The Minimum Viable Product (“MVP”). During this stage, the main priority is development speed and validation. There is a difference between developing something for mass production and developing something for a temporary local production line. In this section, the first design sprint will be described, which took place over a period of two weeks, beginning on 9 March 2020. The desired result of this first design sprint was a working prototype. Such ‘proof of concept’ would later allow the team to attract additional funding and government approval. In section 3.2, there is a description of how this prototype became the benchmark of an upscaled operation for a small production line, which eventually produced the first 100 respirators.

After finalizing a working prototype, a second effort was made to improve the design of the mask with the generated knowledge, in order to adapt production to a larger scale. This time, a more traditional methodology could be used since the previous phase had resulted in sufficient production knowledge. The goal of this second stage was to manufacture 100 respirators per day, which exceeded the initial request from UZA for between 150–300 respirators per week. The priority in this stage had shifted to reliable and fast production at a larger scale, while still maintaining the quality performance aspects of the mask that would result in an effective product. In this second stage (Phase B) both the design and production environment were optimized for production at a small scale and future upscaling possibilities.

Fig. 1 provides an overview of the major development steps in both Phase A and Phase B, shown chronologically in a timeline. Eight different sub systems have been iterated over the course of four weeks. The final design of the MVP is shown in black. The selected solution for the upscaling is shown in dark grey. Table 3 provides a written overview of the components from which FFRs are typically composed, some important considerations in their selection, and then a summary of the material or processing that was chosen for these components in both Phase A (sprint for MVP) and the Phase B (upscaling production).

Fig. 1.

Overview of the 4-week chronological development process ending with the Minimum Viable Product (MVP) (black boxes) and Upscaled production (grey boxes). This chronological development is separated into material choices, processing and production steps necessary to manufacture a respirator mask, including filter material selection and processing, shape or design of the respirator, welding of panels, nose bridge, foam for sealing around the nose, elastics used for the head harness, exhalation valve and packaging.

Table 3.

Summary of typical components in a filtering facepiece respirator, important considerations in the selection or processing of material, and the final material or process employed for each component in Phase A or Phase B.

| Respirator Components | Considerations | Phase A (Sprint for MVP) | Phase B (Upscaling) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The filter material | The most crucial element of a respirator mask is the filter material, this material must be able to filter the virus. The material must be tested according to EN149. | PTFE nanofilter media for FFP2 or FFP3 classes. FFP2 media was in A4 sheet format. FFP2 media was on a roll | Same as Phase A |

| A protective layer | On the outside there should be a layer that protects the user from fluid spatter (blood, coughing). | Spunbond Polypropylene sheet (PP), 50 g. | Same as Phase A |

| A layer for comfort | On the inside of the mask there should be a layer against the skin for comfort and moisture absorption. | Spunbond Polypropylene sheet (PP), 30 g. | Same as Phase A |

| Welded edges | The edges of the masks should be attached together without perforating them. Regular sewing is not an option. | Ultrasonic cutting and point welding by hand. | Ultrasonic sewing machine, Cobot point weld, ultrasonic cutting by hand |

| Nose bridge | The nose bridge must be easy to bend but must be able to retain its shape afterwards. | Aluminum strip, 3.5 mm wide, 1.5 mm thick and 102 mm long. The thickness is crucial and will have to be adapted to the specific rigidity of your design. | Same as Phase A |

| Foam strip | Find a foam strip that is very soft. Chamfer its edges. | A Rolyan Low-Tack Polycushion Padding foam strip (latex free) with a hardness of 3 Shore A. 100 mm long, 20 mm wide and chamfered at 25 mm for the best fit to the face. | Same as Phase A |

| Head straps | The chosen head strap is a non-adjustable type made from elastic. Therefore the elastic band must have a good extension coefficient, to pull the mask firmly to the face. They should not lose their elasticity over time. Use non-latex materials or similar so the elastic bands do not slide of the back of the head. | Non-latex straps of polyisoprene were selected for this application. Width was fixed at 6 mm wide for optimal balance between strength, comfort and adaptability to various head sizes. | Same as Phase A |

| Strap attachment | The straps must be securely attached to the mask without perforating the mask. These attachments must be mechanically tested so they cannot come loose. | A Rapid 106E electric stapling machine was selected for this application. Type 66/6 staples were used, which created the necessary holding strength for the polyisoprene straps. | Same as Phase A |

| One-way valve (FFP3) | For most FFP3 masks, the filter material is difficult to breathe through. This could be dangerous for a multitude of reasons. Breathing out should be then facilitated with a one-way valve. | A new valve was designed and patented. It was designed specifically for 3D printing and rapid production. | Same as Phase A |

3.1. Phase A: Development of the minimum viable product

3.1.1. Reverse engineering

The first step of product development is reverse engineering and morphological mapping. This is generally done by creating a map that includes every sub-part of the product, generating a multitude of design ideas for each sub-system and subsequently selecting and matching the best design ideas. The result of such a process is illustrated in Fig. 1 and Table 3.

A fast way of gathering information about a certain product is to look at existing or similar products on the market. The process of analyzing a product to learn about its design is called reverse engineering [32]. The team reverse-engineered an commercially-available three panel, flat-folding FFR commonly used by local hospitals, to quickly gain enough knowledge about FFRs to kick-start the development of an in-house model. Reverse-engineering enabled information to be gathered quickly about size, materials, production process, assembly, performance and other factors. One of the first things to become clear during the reverse-engineering process was that a respirator’s nose bridge, foam strips and head harness are crucial components for ensuring a good face fit, which is essential for a proper seal. When observing existing respirator designs, it became apparent that these elements are easily underestimated and swapped for cheap sub-quality materials. However, these three components need to be thoroughly researched and precisely matched to create a functional respirator. It was challenging to locally source good materials for these elements, but without a good face fit an FFP2/3 respirator is useless.

3.1.2. Sourcing and processing

The sourcing of materials was a big roadblock to starting up a production line during a global pandemic. A worldwide supply chain disruption caused shortages. This deficiency is being caused by an exponentially growing demand for PPE, panic buying of common items and the temporary shutdown of factories and logistics companies.

Sourcing was challenging due to a high dependency on international suppliers. Due to regional lockdowns and the closure of factories, suppliers and logistics companies, as well as governments requisitioning stocks, resources became hard to find internationally. It therefore became clear that local suppliers had to be identified so that materials could be accessed quickly. However due to globalization, many of these supply companies had moved to cheaper countries such as China [33]. Further, even when materials were offered by lesser-known international suppliers, their quality was questionable. A lack of Europe certification prevented the Antwerp Design Factory team from using these materials in our prototyping.

To enable prototyping to begin as swiftly as possible, small quantities of sample materials from local suppliers were used to make first proof of concept prototypes. Those limited quantities of materials were easy to obtain while waiting for larger batches of materials to arrive. Examples of materials our team sourced are shown in the chronological development timeline in Fig. 1.

The key material for a filtering facepiece respirator is arguably the filtering material that stops viral penetration. Most commonly, melt blown fibers are used for the fabrication of filtering face pieces. It is a one-step production process that produces self-bonded fibrous nonwoven membranes directly from polymer resins, with an average fiber diameter ranging between 1 and 2 μm. This material has proven to be highly effective at filtering nano sized particles [34]. The fibers are then electrostatically charged using a corona treatment process to achieve a higher filtration without increasing the pressure drop [35].

However, this manufacturing process is difficult and costly to set up. As a result, stocks became quickly depleted, and global demand was higher than the global production volume. This resulted in material prices increasing by up to 25 times the normal price [36]. Since the pore size and electrostatic charge of feasible filter materials must be known to evaluate the effectiveness of filtration [37], only few potential alternative materials were available. Since the team did not have the resources and infrastructure to test the actual filtration performance of materials, fabrics with already known certified filtration properties were selected. One of the most commonly-used filtration rating systems are HEPA and MERV [38].

According to the EN149:2001 + A1:2009 standard, an FFP2 mask must filter >94 % of sodium chloride (NaCl) aerosol particles and an FFP3 mask must filter >99 % of NaCl aerosol particles. These values can be translated respectively to MERV 16/17 or HEPA E11/E12 [39]. HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) filters are commonly used in HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) installations, swimming pools, air purifiers, vacuum cleaners and other applications. According to EN 1822−1:2009, true HEPA (H13) requires 99.95 % removal of particles with a diameter of 0.3 μm. This level of filtration is considerably higher than the requirements for FFP2 and FFP3 filtration. This would result in a higher pressure drop compared to masks made from melt blown fibers, and respirator made from true HEPA would be harder to breathe through. To strike a good balance between performance and breathability, the team selected a thin film nanofilter media, based on a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) porous membrane, which is thermally bonded on either side with a polyethylene (PE) or polyethylene terephthalate (PET) non-woven liner. Two different thin film nanofilter media were selected based on the expectation that they would fulfill the requirements for the respective FFP2 and FPP3 classes.

Another important part of the three-panel folding facepiece respirator’s architecture is the foam strip that covers the nose. Most of the outline of the masks is in contact with softer parts of the face. The nose is not capable of compressing as much as other parts of the face. Therefore, it is important to cover this part of the mask with a soft foam-like structure to seal all possible gaps between the nose and the mask. Sourcing this material proved to be harder than anticipated. To achieve a good seal, the material must have several specific properties such as the right hardness, a closed cell structure to stop leaks, biocompatibility, non-toxic, latex-free, easy to cut and have one side covered by pressure sensitive adhesive. With the help of a Portacount Respirator Fit Tester 8038 (TSI Inc.), several materials were tested for their ability to create a good seal. These tools are further discussed in section 3.1.3. Fig. 2 shows the results of quantitative fit testing of the team’s prototype using a 1.5 mm-thick foam with 10A Shore hardness from VMX Silicon and comparing this to 3.2 mm-thick Polycushion Padding Sheet from Rolyan. The respirator prototypes were tested three times using the N99 test setting of the Portacount, where a pass mark for face fitting is a score better than 100. The median face fitting score for the VMX foam was around 320 and the Polycushion was around 360. Both prototypes demonstrate satisfactory performance for FFP3 respirators. After verifying many materials, Rolyan Polycushion Padding appeared to strike the perfect balance between performance and user comfort. This material was designed for medical use as a versatile liner for splints (Rolyan Polycushion Padding Sheet, Performance Health, Warrenville, IL, USA), and so the team could directly use this material for a healthcare application with high certainty of safety and success. The aluminum nose bridge was supplied by a local arts and crafts store. Several colors were validated and were reported to have diverse gluing performance depending on the selected surface treatment. Non-woven PP sheets both 30 g/m² and 50 g/m² were sourced with relative ease from a local company (Voltex NV, Torhout Belgium). Elastic straps were also easy to source, however after evaluating several types it became clear that they needed to meet several requirements. The straps had to be latex free, which highly limited the available choice. Another essential factor was a high elasticity and an elongation factor of at least 300 %. High elasticity is needed to ensure a tight seal for a range of different head sizes, whilst not pulling too hard on larger heads leading to discomfort. It was eventually possible to find an elastic strap material that would be adequate for a minimum viable product.

Fig. 2.

Overall Portacount scores from VMX Silicon 10A 1.5 mm and Rolyan Polycushion 3.2 mm. The bold, horizontal reference line indicates the minimum score necessary to pass a Portacount face fitting test in the N99 mode.

3.1.3. In-house testing

As noted above, filtering facepiece respirator certification is a challenging process. However, rapid in-house validation methods had to be identified to objectively validate the quality of the protypes during the design process. For this purpose, the team selected three tools: 3 M™ Qualitative Fit Test Apparatus FT-30 (3 M, Minnesota, US), Portacount respirator Fit Tester 8038 (TSI Inc. MN, US) and a Fluke 922 Airflow Meter to build a breathing resistance instrument around.

3.1.3.1. Qualitative fit testing: 3 M™ qualitative fit test apparatus FT-30

The FT-30 is a test kit that includes a see-through hood that can be placed over the shoulder of the test subject wearing a mask. A nebulizer is used to disperse aerosols of a mixture of water, sodium chloride and denatonium benzoate into the hood. A series of standardized tests are performed by the user. This method is used to verify the mask to face seal. When the seal is not completely closed, the user will taste the bitter aerosols which verifies a leak. This method is used by hospitals around the world to verify mask fit before entering a contaminated environment. This test was used initially by our team to quickly verify the mask fit during the early design process. However, this test kit is unsuitable for subtle refinements in mask design. This method also cannot be used to test the filtration properties of the mask.

3.1.3.2. Quantitative fit testing: portacount respirator fit tester 8038

A switch was therefore made to a more trustworthy method of testing using a quantitative tool: The PortaCount Pro + Respirator Fit Tester 8038 (TSI Inc. MN, USA). This quickly became the most important machine for testing respirators. As described by [40] the PortaCount compares the number of aerosols inside the respirator (Cin) with the number outside the respirator (Cout). A fit factor is generated that is equal to the ratio of these two measurements (Cout/Cin). To comply with the OSHA requirements a fit factor of 100 should be achieved for N95 respirators. This means that the air inside the respirator is 100 times cleaner than the air outside the respirator, within the measurement range. More specifically, the PortaCount 3038 measures a concentration range from 0.01–5 × 105 particles/cm3 with particle sizes from 0.02 μm to greater than 1 μm [41].

The fit factor is determined by the total inward leakage. This leakage is the sum of the particles penetrated through the filter material and through holes due to insufficient fitting to the face. When the filter media is certified and complies to the desired filtering requirements, the PortaCount can be used to analyze the fit of newly generated prototype FFRs.

3.1.3.3. Breathing resistance measurement

It is important to understand the breathability of the components that are used in a filtering facepiece respirator. This includes the filter material, any non-woven fabrics used and the breathing resistance of an exhalation valve. To quantify the breathability of material or components, a Fluke 922 Airflow Meter (Fluke Corporation, WA, USA) was used. Our team devised a back pressure measurement system was which used inlet pressure from an AP-50 air pump (VT Velda BV, Belgium), capable of generating a maximum flow of 5.5 L/min to simulate breathing through the material. A small pressure chamber was 3D printed from polylactic acid (PLA) filament using fused deposition modelling (FDM), which had adapters for tubes and a seat to make a tight seal with the test material. A cross-section schematic of the setup is shown in Fig. 3 , where the red indicates a foam sealant adhered to the exposed seat of the pressure chamber. The air flow meter was connected to the back side of the valve to measure the back pressure there, which provides an indication of the breathability of the component under test.

Fig. 3.

Cross-section schematic of the breathing resistance measurement setup used in this work. The thick black line shows the 3D printed pressure chamber, the red line shows the foam sealant which makes an air-tight connection between the pressure chamber and the material under test (in this illustration: an exhalation valve) (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

This setup was used to measure the breathing resistance of commercially-available masks and samples of filter media that our team would source. An example of this is shown in Fig. 4 , where the back pressure was measured at high and low flow pump rates (5.5 L/min and 2 L/min, respectively) for a standard Type-I surgical mask, a 3 M Aura 9320 + FFP2 respirator, and a 3 M Aura 1883 + FFP3 respirator. Samples of the FFP2 and FFP3-class PTFE nanofilter materials were also measured. Importantly, Fig. 4 shows that at both low and high flow rates, the melt-blown filter media in the two 3 M respirators are more breathable than the PTFE porous membrane used in our team’s prototypes.

Fig. 4.

Breathing resistance of commercially-available surgical and respirator masks compared against the thin film nanofilter media used in the respirator prototypes, measured a high and low flow rates.

3.1.4. Exhalation valve development and validation

Due to the high filtration efficiency of the FFP3-class PTFE nanofilter, breathability issues were likely to present themselves compared to conventional melt-blown polypropylene filter media. The way commercial FFP3 facemasks work around this is to install a one-way valve to assist the exhalation of the wearer. A novel design was made for an exhalation valve that is optimized specifically for 3D printing and local assembly, which comprises of three 3D-printed rigid valve bodies, a flexible diaphragm to create the seal made from a latex material, which is secured to the filter material of the respirator using an M3 stainless steel cap screw and nut. The exhalation valve is a based on an umbrella valve working principle, holding the flexible diaphragm under conical tension against the rigid valve body. The valve assembly is covered with a small piece of 50 g/m2 polypropylene to protect against fluid splatter, which is secured in place with a zip tie. An exploded view of the assembly is shown in Fig. 5 .

Fig. 5.

Exploded view of the valve design optimized for 3D printing and local assembly. From left to right showing the M3 stainless steel nut, back cover, mask layers, valve bottom, valve diaphragm (in red), valve top, M3 stainless steel cap screw, protective splatter cover and zip-tie (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

3D-printing as a fast response production method was used very successfully during the pandemic. Digital production files can be made open source and shared to enable rapid global production by communities, individuals, universities, corporations and government [42].

As previously identified by Bezek et al., several factors such as geometric design constraints and print orientation have impact on the shell porosity of 3D-printed respirators as well as the material choice [43]. They concluded that most 3D-printed respirators performed poorly even though testing was done with the approximation of a perfect respirator-face seal. Following these findings, caution was advised when selecting a suitable material.

The polymer selected for 3D-printing of the exhalation valve determines the performance, including material leakage and sealing against the diaphragm, which means that it is essential to choose an optimal material. The breathability of different materials was compared to identify the best material for the valve body. Seven valves comprised of different materials were 3D printed: (1) Fused Deposition Modeling Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (FDM ABS), (2) Fused Deposition Modeling Polyethylene terephthalate (FDM PET), (3) Fused Deposition Modeling Polylactic acid (FDM PLA), (4) Multi Jet Fusion (MJF), (5) Stereolithography (SLA), (6) Selective laser sintering with a fine finish (SLS fine), and (7) Selective laser sintering with a rough finish (SLS rough). All FDM printed parts were printed in house and MJF and both SLS prints were ordered through external printing services (Materialise NV, Leuven, Belgium). Fig. 6 (a) shows the material leakage that occurred through the walls of the seven 3D prints themselves, typically a wall thickness of 1.5 mm with the void for the flexible diaphragm sealed shut. Fig. 6 (b) shows the leakage of the assembled exhalation valve, with the outward part of the valve body facing inward to the pressure chamber of the team’s back pressure measurement setup. In these figures, the materials are ordered from highest to lowest back pressure, indicating best to worst leakage performance for a one-way valve. Additionally, Fig. 6 (b) also includes diaphragm leakage measurement of a 3 M™ Cool Flow™ exhalation valve, which employs a cantilever valve working principle.

Fig. 6.

Back pressure measurements of (a) the prototype valve design in seven different 3D-printed materials, which indicate leakage through the material itself, and (b) the sealing pressure of the flexible diaphragm against the seven 3D-printed valve bodies, compared to a 3 M™Cool Flow™ exhalation valve. In both figures, the higher the pressure, the better the performance.

These figures show clearly that SLS is not usable without any post processing treatments. Small polymer particles are fused together which results in a rough surface finish as well as a porous printed structure. Fine SLS printing proved more efficient but still performed inadequately. MJF printed parts showed little improvement compared to SLS. While the process differs, polymer particles are being used as well to construct form the print which leads to similar unfavorable performance. This was a concerning result for our team, as the cantilever exhalation valve design included in the CIIRC half face respirator mask is 3D printed using MJF. Our results indicate exhalation valve bodies printed with MJF would not be able to achieve a good seal with a flexible diaphragm. In addition, FDM printed parts were tested in three different materials with PLA showing the most promising results. Several printing-optimizations were put in place to ensure good interlayer adhesion. The prints were made with 100 % infill. All the FDM valves were produced on a higher temperature compared to typical printing temperatures, this results in the plastic becoming softer during extrusion, leading to improved filling of uneven surfaces. Over extrusion is another print setting that was used to improve print quality. By extruding excess material, less air pockets will occur during printing. This technique does, however result in worse tolerances. FDM prints are built up by stacked extruded layers, by optimizing the design of the valve, a small top layer is printed in one continuous, uniform extrusion which results in a very level mating surface for the valve diaphragm leading to a favorable seal. Finally, as expected, the SLA print performed best. Due to its precise micron-resolution and optically transparent printing capabilities it resulted in a completely airtight and shiny smooth surface finish performing similar to the injection-molded 3 M™ Cool Flow™ valve. The team concluded that SLA prints yielded favorable material and performance properties. Large batches of SLA printed valve components were ordered through Materialize NV’s printing services.

3.1.5. Design iterations until the minimum viable product

The prototyping phase was a matter of reverse engineering and fast failing. By using an agile development methodology, the team was able to cycle through all phases of the product development process almost every day. This resulted in a new prototype being produced on a daily basis. These mock-ups were mostly made up of free materials samples from local companies, 3D printed valves, and stapled elastics. In Fig. 7 , an overview of filtering facepiece respirator prototypes is shown, numbered sequentially from 1 to 16. The 16th prototype was the team’s Minimum Viable Product (MVP). All these prototypes were produced during the first two weeks.

Fig. 7.

Prototypes from the first two weeks, numbered sequentially. The 16th prototype was the MVP.

After two weeks, the first completely working proof of concept was created, as shown in Fig. 8 . The prototype consisted of the FFP3-class PTFE nanofilter media, surrounded by spunbond polypropylene on both the outside (PP50) and inside (PP30). The 3D printed valve was effective and safe against blood spatter, the mask and nose-cushion were reasonably comfortable, and the mask could be fitted tightly on the face. A short video of the Phase A process is located here: Product developers work on a possible solution for the respirator shortage.

Fig. 8.

Images of the minimum viable product fabricated at the end of Phase A. (a) front view showing the exhalation valve and point welds performed by hand on the edge of the mask, (b) rear view of mask showing the polyisoprene head harness and the name labelling, and (c) five finished samples sent out for evaluation.

3.1.6. Analysis of the fabrication process

A total of 6 steps were required to create a single mask, with a combined manufacturing time of 35.5 min per mask. All these steps could be performed manually by a single person. This is summarized in Table 4 . It was then concluded that a second design stage was necessary to optimize the production time and ensure the product could be manufactured at a small industrial scale.

Table 4.

Overview of all steps and sub-steps of the production process of the respirator mask fabricated at the end of Phase A.

| Step | Process | Details | Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Laser cutting | A. Cutting & fusing 3 layers: PP30-PTFE nanofilter-PP50 | 5 |

| 2 | Ultrasonic Welding | A. Upper panel (1 seam) | 3 |

| B. Lower panel (1 seam) | 3 | ||

| C. Three panels together (2 seams) | 6 | ||

| 3 | Nose bridge | A. Preparation and applying glue | 2 |

| B. Applying nose bridge | 0.5 | ||

| 4 | Foam | A. Cutting out the shape | 1 |

| B. Applying strip | 1 | ||

| 5 | Exhalation valve | A. 3D printing | 0 |

| B. Assembly | 8 | ||

| 6 | Elastic bands | A. Cutting to size | 2 |

| B. Stapling | 4 | ||

| Total Time: | 35.5 |

3.2. Phase B: production ramp-up

3.2.1. Final production architecture

In the second phase (Phase B), a small-scale production line was developed that could make more than 100 masks per day. An overview of the production steps is shown in Fig. 9 .

Fig. 9.

Overview of the 10 production steps of the scale-up production. Step 3a is an ultrasonic sewing machine, Step 3b is semi-autonomous ultrasonic point welding using a Cobot, and Step 4 is a manual ultrasonic cutting station.

3.2.2. Prioritization of the production line

In order to further optimize the production of FFRs, some adjustments were necessary. A first change was mounting the rolls of filter material and spun-bound polypropylene materials on a fixed gantry frame, which then required less preparation time per respirator. In addition, the team gained access to a clean new laser cutter that would help minimize contamination. Next, an ultrasonic sewing machine was made and put into use for welding and cutting the seams of the upper and lower panels. In this way, much more consistency in the seams of the mouth mask was achieved. It also significantly reduced the time needed for manual ultrasonic point welding. Furthermore, a cobot was programmed to weld the three different panels together. This required a small adjustment to the shape of the filtering facepiece respirator which made it possible to fix it in a predetermined position underneath the cobot. In this way, the cobot arm could weld the panels together considerably faster and more consistently than a single person. Each of these changes is described in more detail in the following sections.

3.2.3. Production process development

The transition from making a few masks per day to a 100 masks per day required the assembly of a small-scale production line. At this point all the required techniques had been identified which resulted in the development of seven substations on the production line: (i) laser cutting the fabric layers, (ii) welding the separate panels, (iii) welding the three panels together, (iv) stapling the headstraps, (v) gluing the nose bridge, (vi) attaching the nose comfort cushioning and (vii) attaching the exhalation valve. Each station underwent multiple optimization cycles that are detailed in this section.

3.2.3.1. Shape

The starting point to determine the new respirator shape was a three-panel, flat-folding FFR used by UZA. These FFRs were the preferred product of the healthcare workers but were no longer available due to supply chain failures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The flat-folding FFR’s shape was scanned and converted into digital drawings. The three-panel design was prototyped into a functioning respirator using the techniques explained further in this section. Using the only available anvil for the sonotrode resulted in wider welding seams compared to the commercially available design. A final adaptation was made by adding outside clamping points to the straight edges of the shape, to fix all three panels in a magnetic clamping jig during the cobotic welding. The final design is shown in Fig. 10 .

Fig. 10.

Digital design of the chin, front, and nose panels of the Antwerp Design Factory respirator, including the mounting points to stack and secure the panels for ultrasonic point welding with the cobot.

3.2.3.2. Filter: laser cutting the PTFE and PP-layers

As previously described, the three-panel folding facepiece respirator consists of multiple layers: a polypropylene outer layer of 50 g/m², a PTFE nanofiltering layer and a polypropylene inner layer of 30 g/m². Laser cutting was chosen as the most suitable technique for cutting the necessary shape out of the different layers. The adaptability of this technique made it possible to quickly reiterate in the design process and prototype and experiment with new shapes and materials. A second reason for this choice of the laser cutting technique was because in-house laser cutters such as the BRM 6090 (BRM lasers, Winterswijk, The Netherlands) could be used. The best results were achieved with a cutting speed of 100 mm/s and a laser power of 40 %. The PP-layers and protective layer were manually cut using clean scissors in A4 sizes to match the size of the sample filter material. Instead of laser cutting each layer separately, the four layers were stacked before laser cutting to get a perfect interlayer alignment. As the work area was limited to A4 size, enough material for one of each three panels of the mask was available. Stacked layers were lightly fused when cut simultaneously, which also resulted in better alignment during ultrasonic welding. It took 36 s to cut one mask (10 masks in 5 min).

To enable upscaling to 100 respirators per day, several improvements had to be implemented. A new Trotec Speedy 400 (Trotec Laser B.B., Haaksbergen, The Netherlands) was used for sterile production. Filter material was sourced on rolls as opposed to individual sheets, therefore making it possible to use the full work area of the machine. The Trotec Speedy 400 has a slightly larger working area (600 × 1000 mm) than that of the BRM 6090 (600 × 900 mm). By implementing these upgrades, all the panels of a complete mask could be cut in just 17 s. This improved cycle time was achieved by implementing Trotec’s cutting speed of 500 mm/s and by optimizing the nesting of the panels with an open-source software called Deepnest (Jack Qiao, Vancouver, Canada). The use of advanced nesting also enabled waste to be minimized.

Ultrasonic welding is one of the most common techniques used in the production of polypropylene based FFRs. At first, the three panels of the prototype models were spot welded by hand using a 70 kHz flat-head type cutting-sonotrode on a Rinco Ultrasonic Generator 35 kHz GM35−600 (RINCO ULTRASONICS AG, Romanshorn, Switzerland). 3D-printed stencils of the three panel shapes were fabricated by our team and were used to transfer guiding lines on the panels to ensure precise placement of the spotwelds. Three millimeters proved to be the ideal distance between spotwelds. This distance ensures sufficient flexibility in the seam while maintaining an airtight seal. A total of 288 spotwelds were required per respirator: 66 on the nose panel, 82 on the chin panel and 77 spotwelds per weld line to combine the three panels. Clips were used to keep the panels aligned during welding. The combined process took around 12 min to complete. This manual process resulted in irregular spacing among other inconsistencies, leading to unreliable mask performance. A repeatable process therefore had to be identified to enable upscaling.

To improve the welding quality of the chin and nose panels, the manual welding method was replaced by an ultrasonic sewing machine that was equipped with a titanium rotating anvil with a toothed-wheel and the cutting blade, as shown in Fig. 11 . A drive system was added for the anvil to enable automatic feeding of the material. This driving system was linked with the activation pedal of the ultrasonic welder. This configuration meant that the functionality of this machine was comparable to an industrial ultrasonic sewing machine.

Fig. 11.

(a) Modified ultrasonic sewing machine and (b) close-up of the sonotrode and rotating anvil with a toothed-wheel and cutting blade.

In order to improve and speed up the welding of the three panels, a Franka Emika Panda 7-axis cobot (Franka Emika GmbH, Munich, Germany) was introduced to the production. A Cartesian coordinate system was used to define the position of the welding points, show in Fig. 12 . The X and Y coordinates describe the planar position of the points, while the Z coordinates are used to define the applied pressure of the end effector.

Fig. 12.

The X and Y coordinate system used to define the welding points for the cobot.

After completing the robot welding, the holding points were removed by cutting them with the ultrasonic cutting tool.

3.2.3.3. Elastics: stapling the head straps,

Each filtering face piece requires two head straps to adequate secure it to the user’s face. A non-latex material with a high tensile strength was selected (TheraBand, Ohio, U.S.A.). Initially, large sheets were cut by hand with rotary cutters. The cutting performance of a rotary cutter is considerably better compared to conventional utility knives, because rotary cutters apply pressure perpendicular to the material. Around 10 s was needed to cut out a single strap, resulting in a 20 s production time per mask. A conventional office stapler was used to attach the elastic bands to the facemask. Two staples were required to try and eliminate slipping over time. Later, a stronger stapler was used which delivered a more consistent pressure but slipping during use was still a problem. Finally, the team moved to an industrial electronic stapler, Rapid 106E (Rapid Electronics Ltd, Essex, United Kingdom) with an adjustable force setting. Combined with high strength stainless steel staples, this resulted in a greater holding strength which eliminated slippage.

3.2.3.4. Nosebridge: gluing the nose bridge

For the nose bridge, an annealed flat aluminum square wire (1.5 × 3.5 mm) was selected and cut to length by hand with side cutters. Given the simplicity of this process, automation was not necessary to improve production speed. Therefore, the same method was used throughout the whole process, allowing for flexibility.

To attach the nose bridge to the mask, a high-end hobby hot glue gun (Steinel Gleumatic 5000, Steinel Group, Clarholz, Germany) was used. After gluing, a palette knife was used to apply even pressure during the solidification of the glue. To prevent the nose bridge from peeling off, an extra dot of glue was applied on top of both sides of the aluminum strip.

3.2.3.5. Foam: attaching the nose comfort cushioning

A 3D-printed template was used to transfer the design of the comfort cushioning on the selected Rolyan Low-Tack Polycushion sheets. The foam strip follows the outline of the nose panel of the mask. After cutting out the strips with scissors, it was attached by hand using the pre-applied pressure-sensitive adhesive backing.

3.2.3.6. Valve: attaching the exhalation valve

The increased filtration of FFP3 masks results in a higher pressure drop, which correspondingly makes the mask harder to breathe through. To eliminate sub-optimal breathability and moisture and CO2 buildup, a one-way exhalation valve is required. An exhalation valve was 3D-printed in three parts, while an M3 nut and bolt were used to assemble all parts and fix a circular disc into place which acts as the valve membrane diaphragm. The membrane was punched out of stacks of the same elastic material as the head straps.

3.2.3.7. Packaging

The requirements for CPA evaluated by IFA is that the respirator needs a name, that the respirator has labelled packaging, and that a manual for usage is included. Our team chose to call the respirator the ADF3 (Antwerp Design Factory FFP3), and respirators were packaged in zip-lock bags with printed adhesive labels attached to indicate product code details. Finally, usage instructions were created that described donning and doffing procedures and disposal of the respirators.

3.2.4. Human-Machine interaction as a smart and resilient production tool

A previous study concluded that the flexibility of many manufacturing methods has difficulties adapting to changes since they are constrained within a very limited boundary. Robots, particularly cobots, in combination with modern manufacturing technologies can prove useful to ramp up production in emergency situations. This was shown in a case study about emergency ventilator production [44].

To enable the team to make the production process faster and more consistent, a Franka Emika Cobot was used. This resilient manufacturing robot allows for easy programming and configuration. Combined with a clamping jig, the three panels could be aligned and welded accurately and consistently using a custom program. To achieve consistent pressure, a 3D-printed end-effector for the sonotrode was designed with a built-in spring system, as shown in Fig. 13 . This allowed the sonotrode (which was initially developed to be used for cutting) to be mounted at an exact angle and weld with a consistent pressure. A total of three jigs were used so the production line user can replace the welded mask with new panels, enabling the robot to work without interruption. A short video of the ultrasonic fabrication process is shown here: Robotised Ultrasonic Welding Process for an Emergency Mouth Mask Production Line during the COVID-19.

Fig. 13.

Franka Emica Cobot end-effector equipped with a 3D printed sonotrode mount, attached at an angle, featuring a linear compression spring and bearing system in the Z-axis.

3.2.5. Analysis of the production steps

A small assembly of six people was arranged to sequentially assemble the individual components of the FFRs. Using this approach, more than 100 respirators were able to be fabricated in an afternoon, following the steps outlined in Fig. 9. The interaction between the stations can be seen in this video summary: Product developers produce first 100 masks (april 2020).

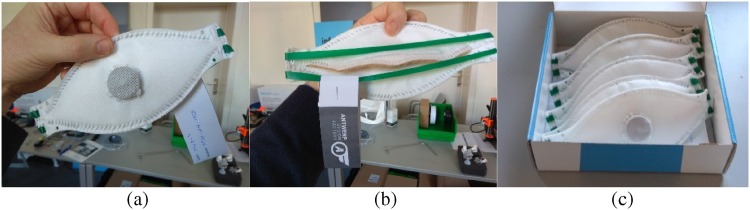

In Table 5 , an overview of the improved production is shown. It shows a total production time of 553 s per mask during Phase B, of which nearly 200 s were material preparation steps. In Phase B the team used six people in the production line. This resulted in 120 masks being produced in 4 h, which equates to 30 FFRs per hour. This was a significant improvement from Phase A, which required 35.5 min per respirator. Even if six people were used in Phase A to simultaneously perform the individual preparation and production steps, the slowest station, manual ultrasonic point welding which took 12 min, would limit the yield to only 5 FFRs per hour. Photographs of the fabricated masks first are shown in Fig. 14 .

Table 5.

Overview of production timing at the end of Phase B, adding up to a total preparation and production time of 553 s per mask.

| STEP | PROCESS | DETAILS | TIME (sec) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Preparation | A. cutting nose bridges | 6 |

| B. Cutting foam | 90 | ||

| C. Cutting elastic bands | 30 | ||

| D. Cutting fabrics to size of laser cutter | 9 | ||

| E. Prepare labels | 60 | ||

| 1 | Laser cutting | A. Cutting & fusing 3 layers: PP30-PTFE nanofilter-PP50 | 15 |

| 2 | Ultrasonic Welding | A. Upper panel (1 seam) | 15 |

| B. Lower panel (1 seam) | 15 | ||

| C. Cobot: Three panels together (2 seams) | 80 | ||

| D. Cutting off the holders | 10 | ||

| 3 | Elastic bands | A. Stapling | 45 |

| 4 | Nose bridge | A. Preparation and applying glue | 15 |

| B. Applying nose bridge | 15 | ||

| 5 | Foam | A. Applying strip | 3 |

| 6 | Exhalation valve | A. Assembly | 60 |

| B. Testing valve | 5 | ||

| C. Applying valve cover | 15 | ||

| 7 | Quality control | A. Check for visual and mechanical faults | 50 |

| 8 | Packaging | A. Apply label | 5 |

| B. Place in packaging | 10 | ||

| Total Time: | 553 |

Fig. 14.

(a) The front and (b) back of the final fabricated respirators, and (c) 20 of the 120 respirators at be shipped to IFA in Germany for CPA accreditation testing.

4. Validation with CPA from IFA and Belgian ATP

Of the 120 respirator masks fabricated on the afternoon of 10 April 2020, 20 were sent to IFA In Germany for the CPA accreditation (received 14 April 2020) and 15 were sent to Mensura for the Belgian ATP respirator mask procedure (received 16 April 2020).

On 27 April 2020, we received the results of the ATP procedure from Mensura. The ADF3 respirators received an evaluation as “Okay to Use” and certificate number ADF1−000032. This certificate remains valid for as long as the ATP protocol is supported by the Belgian federal government. This certificate is included in Appendix A.

On 28 April 2020, we received the test results from IFA. The ADF3 respirator model had passed all tests in the CPA protocol and certificate number 202021467/2120 was provided as the designator for our respirator. This certificate is valid until 27 April 2021. This certificate is also included in Appendix B.

Once these certifications were in place, the remaining 85 masks were transported to UZA for their use. A short summary of this delivery is shown here: First delivery of respirators to UZA.

5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic created a unique set of circumstances: a major Belgian university hospital requested that a university research group establish an emergency production line of respirator masks. This was to ease chronic PPE shortages in European hospitals due to global supply chain failures. The Antwerp Design Factory answered this call for help and designed and fabricated respirator masks that fully met the hospital’s expectations and European safety regulations. Apart from a broad objective to produce between 150–300 FFP2 or FFP3 respirators per week for UZA, the team was given little input or guidance. An agile product development process was therefore implemented to overcome uncertainties. The team’s efforts are a successful case study of resilient and smart manufacturing in the COVID-19 pandemic.

There were two distinct phases in this project: Phase A and Phase B. Phase A consisted of a sprint towards a minimum viable product which satisfied the team and the hospital’s requirements for performance and comfort. During Phase A, the sprint approach required team members to take responsibility for different aspects of the respirator development. This included sourcing, evaluation of fabrication techniques, and respirator performance testing benchmarked against the EN149 standard. Phase A features two novel developments which are examples of additive and rapid manufacturing as a resilient manufacturing method. The first novel development was the team’s rapid development of a 3D-printed exhalation valve that could be assembled in the respirator. The second key contribution is the analysis of seven different types of 3D-printed materials, to determine leakage through the material itself and the material’s ability to form a tight one-way seal with a flexible diaphragm. This analysis revealed that MFJ printing material was unsuitable for use in an exhalation valve. This conclusion furthers the state of the art and is in contrast other groups working with the HP MJF platform across Europe as a fabrication means for half-face respirator masks. Phase A culminated in the team’s MVP, which was a three-panel flat-folding filtering facepiece respirator. The MVP was fabricated by hand and took 35.5 min to manufacture. An analysis of the Phase A fabrication process revealed that the manual ultrasonic welding would limit production yield. In addition, the manual spot welding is a very tiring process. This is because a hand-held ultrasonic welder is awkward to control and tiring to use for extended periods, due to factors such as the weight of the hand-held pen, the driving cable and the air-cooling line.

Phase B refers to the team’s upscaling strategy to move from the MVP to the reliable production of 100 respirator masks. An important decision in this phase was to utilize a cobot to perform the repetitive ultrasonic spot-welding tasks. The use of the cobot in this application is an example of innovative adaptation of human-machine interface. The cobot added resilience to the team’s production line, as it removed human error (for example caused by fatigue) from the fabrication process. An important secondary contribution was the development of a novel spring-loaded end-effector for the cobot to hold the pen-shaped ultrasonic welder. Again, 3D printing was employed as a smart manufacturing solution which allowed the design of the end-effector to be rapidly iterated. This meant that the cobot could apply spot welds that would mimic the feel or touch that a human operator could achieve.

Ultimately, 120 respirator masks were manufactured in a single afternoon using the Phase B production plan outlined. Of these masks, 20 were sent to IFA for the German CPA testing and 15 were sent to Mensura for the Belgian ATP. The ADF3 respirator passed both these certification procedures, and the remaining ADF3 respirators were shipped to UZA. The hospital could therefore be certain that the Antwerp Design Factory’s respirators fulfilled all relevant European and Belgian regulatory requirements.

Author contributions

The following statements describe the contribution of each Author: Study conception and design: Vanhooydonck, Watts, Verlinden, Van Goethem, Van Loon, Verwulgen; Acquisition of data: Van Goethem, Vleugels, Van Loon, Vanhooydonck, Stokhuijzen, Smedts; Van Camp, Veelaert; Analysis and interpretation of data: Van Goethem, Peeters; Drafting of manuscript: Vanhooydonck, Van Goethem, Van Loon, Van Dormael, Watts; Critical revision: Watts, Vanhooydonck; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to the KU Leuven Robotics Research Group, Flanders Make, Universitair Ziekenhuis Antwerpen, and M.D. Ignace Demeyer from Onze Lieve Vrouw Ziekenhuis, Aalst. This research was funded by the Industrial Research Fund (IOF) of the University of Antwerp, grant number FFI200119, and a generous donation from Fondation d’enterprise Carrefour.

Biographies

Andres Vanhooydonck (Faculty of Design Sciences) is a doctoral student at the University of Antwerp specializing in system design, rapid prototyping and additive manufacturing. In his doctoral research, he investigates how 3D-printing can enable Lab-On-A-Chip technology to become more accessible for applications such as Point-Of-Care Testing.

Sander Van Goethem (Faculty of Design Sciences) received a mandate from the Fund for Scientific Research (FWO) for his research on 'immersive 3D modeling'. In his doctoral research, Sander Van Goethem investigates how product developers (designers) can use Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR) and / or Mixed Reality (MR - mixing the real and virtual world) in the design and product development process.

Joren Van Loon (Faculty of Design Sciences) is a doctoral student at the University of Antwerp with a special interest in ecodesign. His doctoral research investigates how current lab technologies can be used in on-site situations in a sustainable way. Minimizing the current waste inside and outside the lab is one of the main goals.

Robin Vandormael (Faculty of Design Sciences) is a doctoral student at the University of Antwerp with a focus on technical development, additive manufacturing, high-end prototyping and immersive technologies. He does his PhD on the validation of immersive technologies, including mixed reality, for mission-critical teamwork in emergency response, more specifically for firefighting departments.

Jochen Vleugels (Faculty of Design Sciences) is a doctoral student at the university of Antwerp on the topic of development tools for near body products. Ranging from mathematical human models to 3D scanning to physical prototyping. On a daily basis the focus is placed on prototyping and development of minimal viable product prototypes. Using tools like 3D printers, laser cutters, Arduino, electronics and programming, whatever is needed to make things work!.

Thomas Peeters (Faculty of Design Sciences) is a doctoral student at the University of Antwerp with a main specialization in vibrotactile motion steering, which is an emerging haptic guidance technique for posture and movement corrections by using vibrations.

Sam Smedts (Faculty of Design Sciences) is a doctoral student at the university of Antwerp is a PhD student at the University of Antwerp with a passion for technology-driven design. His research area is focused on data driven product development in the context of smart products (IOT), industry / human 4.0 in combination with machine / deep learning techniques.

Drim Stokhuijzen: Freelance product designer with professional experience at Fuseproject (San Fransico) and Dutch start-up PHYSEE. For Iris van Herpen “Ludi Naturae” haute couture winter collection in 2017 he was responsible for the 3D interpretation (grasshopper) and production (Connex 3D) of the main dress shown. Graduated at Industrial Design Engineering (Delft University of Technology) in 2016. In his master thesis he researched the future of 3D foodprinting at Creative Machines Lab (Columbia University, NYC).

Marieke Van Camp Doctoral student and design coach in user centred design, and design for interaction. Within her doctoral study at Product Development she has participated in research programmes from VLAIO in collaboration with the Flemish industry and the BOF programme. Her research focuses on embodied interaction and research through design. During her PhD trajectory she developed and tested various prototypes.

Lore Veelaert (Faculty of Design Sciences) is a doctoral student at the University of Antwerp with a special interest in sustainability, eco-design and sustainable perception of materials. She is finishing her PhD on User-Centred Experiential Material Characterization, aiming for insights on the relation between material expression and users’ self-identity. She focusses on the material class of plastics (e.g. virgins, recycled plastics, bioplastics) and approaches materials selection from a consumer perspective and segmentation profiles, that involves consumers in a holistic, multimodal and tangible interaction with materials.

Jouke Verlinden (PhD Design Engineering) is Associate Professor Augmented Fabrication, exploring the domains of Augmented Reality and Digital Fabrication for improving (or better: augmenting!) humancentered design.

Stijn Verwulgen (Faculty of Design Science) is full professor at product development with a research focus on the development of design and engineering methods to make data science available in the daily practice of design and engineering. Application domains comprise enriched anthropometry, development of wearables, medical device development and ergonomics.

Regan Watts (Faculty of Design Sciences) is an Assistant Professor in Technology Driven Design. His research interests include medical device development and respirator mask development. He is an expert member in the NBN (Belgian National Bureau for Standardisation) mirror group " CEN CWA 17553:2020 Community face coverings - Guide to minimum requirements, methods of testing and use

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2021.03.016.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Ulrich K.T., Eppinger S.D. fifth edition. fifth edit. 2012. Product design and development. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomke S., Reinertsen D. Agile product development: managing development flexibility in Uncertain environments. Calif Manage Rev. 1998;41:8–30. doi: 10.2307/41165973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horwitz S. Wal-Mart to the rescue private enterprise’s response to Hurricane Katrina. Indep Rev. 2009;13:511–528. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warden Ja S.S. first edit. O’Reilly Media; Sebastopol, CA: 2008. The art of agile development. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Digital Template Market . Digital Template Market; 2020. Why agile is important for software development.https://digitaltemplatemarket.com/agile-important-software-development/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwaber K. Bus. object des. implement. Springer; London: 1997. SCRUM development process; pp. 117–134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck K., Beedle M., Van Bennekum A., Cockburn A., Cunningham W., Fowler M. 2001. Manifesto for agile software development twelve principles of agile software. [Google Scholar]