Abstract

Background

Emergency clinicians have a crucial role during public health emergencies and have been at the frontline during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study examined the knowledge, preparedness and experiences of Australian emergency nurses, emergency physicians and paramedics in managing COVID-19.

Methods

A voluntary cross-sectional study of members of the College of Emergency Nursing Australasia, the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, and the Australasian College of Paramedicine was conducted using an online survey (June-September 2020).

Results

Of the 159 emergency nurses, 110 emergency physicians and 161 paramedics, 67.3–78% from each group indicated that their current knowledge of COVID-19 was ‘good to very good’. The most frequently accessed source of COVID-19 information was from state department of health websites. Most of the respondents in each group (77.6–86.4%) received COVID-19 specific training and education, including personal protective equipment (PPE) usage. One-third of paramedics reported that their workload ‘had lessened’ while 36.4–40% of emergency nurses and physicians stated that their workload had ‘considerably increased’. Common concerns raised included disease transmission to family, public complacency, and PPE availability.

Conclusions

Extensive training and education and adequate support helped prepare emergency clinicians to manage COVID-19 patients. Challenges included inconsistent and rapidly changing communications and availability of PPE.

Keywords: Emergency care, Emergency nurse, Emergency physician, Paramedics, COVID-19, Pandemic

1. Introduction

Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases threaten global health and security [1]. The emergence of COVID-19 in Australia in late January 2020 [2], [3] signalled a national health emergency and precipitated the activation of the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) on 27 February 2020 [4], [5].

Previous research investigating the impact of infectious diseases outbreaks (e.g. COVID-19, Ebola virus disease, Severe acute respiratory syndrome, influenza and Middle East respiratory syndrome) has shown that while emergency department (ED) presentations decreased [6], [7], [8], [9], emergency nurses and physicians and paramedics faced increased stress and anxiety [10], [11], fear of being stigmatised from family and society due to the nature of their work [12], and had elevated concerns for the safety of their families [13], [14].

Recent studies of primary healthcare nurses [15], paediatric physicians [16], infectious diseases physicians and clinical microbiologists [17], [18] in Australia and New Zealand have shown that COVID-19 has had a significant impact on their workload and job security, and have raised significant concerns about risk of infection and the availability of personal protective equipment (PPE). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency clinicians in Australia is not well understood. This study examined the knowledge, preparedness and experiences of emergency nurses, emergency physicians, and paramedics in managing patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 in Australian healthcare settings.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in collaboration with the College of Emergency Nursing Australasia (CENA), the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM), and the Australasian College of Paramedicine (ACP). CENA, ACEM and ACP are the professional organisations representing emergency nurses, emergency physicians and paramedics across Australasia, respectively. Ethics approval was obtained by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Sydney (approval number 2020/20).

2.2. Setting and population

Three separate surveys were distributed by CENA, ACEM and ACP to its membership via newsletters and emails. At the time of distribution, membership to CENA, ACEM and ACP were approximately 1400, 7100 and 5000, respectively. Participation was voluntary and eligible respondents were individuals with active membership to CENA, ACEM or ACP. There were no other inclusion or exclusion criteria. If participants were members of more than one college, they were asked to complete the survey from the college that they most identified with professionally. Submission of a completed survey was defined and deemed as consent to participate.

2.3. Data collection instrument and analysis

The survey questions were drafted by a panel of clinical staff, academics and experts in emergency care and infectious diseases, and were tailored specifically for each individual emergency clinician group. Survey questions were drawn from previous research examining the preparedness and experiences of healthcare workers during large-scale infectious diseases outbreaks [11], [19], [20], [21]. The surveys were developed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) application [22]. Each survey underwent pilot testing and review by expert panels to establish content and face validity prior to distribution. The final surveys comprised of 40 to 45 questions which were a combination of multiple-choice questions and free-text responses (see Supplementary Material). The majority of the questions in the surveys were replicated across the three emergency clinician groups. However, the emergency nurses’ survey contained six specific nursing-focused questions, the emergency physicians’ survey contained three specific physician-focused questions, and the paramedics survey contained nine specific paramedicine-focused questions. Each survey contained four sections relating to the respondents’ a) demographics; b) knowledge of COVID-19; c) preparedness for COVID-19; and d) experiences working as an emergency clinician (e.g. nurse, physician or paramedic) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The surveys were active from June to September 2020. For each survey, raw data was exported from REDCap into Microsoft Excel for data curation and cleaning. Frequencies and descriptive statistics (e.g. median and interquartile range [IQR]) were calculated using SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp. Released 2019, version 26.0). Conventional content analysis technique was used to analyse data from free-text responses.

3. Results

3.1. Respondents and demographics

A total of 183, 129 and 174 responses were received from the emergency nurses (EN), emergency physicians (EP) and paramedics (PARA) surveys, respectively. Responses which did not progress beyond either the survey consent page or the demographics section of the survey were considered incomplete and excluded from data analysis. Therefore, data analysis for this study included 159 responses from emergency nurses (response rate of 11.4% from CENA members), 110 responses from emergency physicians (response rate of 1.5% from ACEM members) and 161 responses from paramedics (response rate of 3.2% from ACP members).

All respondents worked in Australia (Table 1 ). For emergency nurses and paramedics, respondents indicated that they primarily worked in NSW (EN: 45.9%, n = 73; PARA: 44.1%, n = 71), QLD (EN: 16.4%, n = 26; PARA: 17.4%, n = 28) and VIC (EN: 23.3%, n = 37; PARA: 16.8%, n = 27). For emergency physicians, 37.9% of the respondents (n = 44) currently worked in TAS. This was followed by NSW (31.9%, n = 37) and VIC (12.9%, n = 15). Majority of emergency physicians indicated that they worked in a tertiary/teaching hospital (42.7%. n = 47) or a regional/rural hospital (31.8%, n = 35). Other respondents stated that they worked in a metropolitan hospital (16.4%, n = 18) or a private hospital (2.7%, n = 3).

Table 1.

Distribution of survey respondents by region.

| Location | Emergency nurses |

Emergency physicians |

Paramedics |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Australian Capital Territory | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.6 |

| New South Wales | 73 | 45.9 | 37 | 31.9 | 71 | 44.1 |

| Northern Territory | 4 | 2.5 | 2 | 1.7 | 3 | 1.9 |

| Queensland | 26 | 16.4 | 4 | 3.4 | 28 | 17.4 |

| South Australia | 6 | 3.8 | 5 | 4.3 | 18 | 11.2 |

| Tasmania | 3 | 1.9 | 44 | 37.9 | 6 | 3.7 |

| Victoria | 37 | 23.3 | 15 | 12.9 | 27 | 16.8 |

| Western Australia | 9 | 5.7 | 3 | 2.6 | 7 | 4.3 |

The median number of years of emergency care experience was 15 years [IQR: 8–25] for emergency nurses, 8 years [IQR: 3–20] for emergency physicians, and 13 years [IQR: 5–25] for paramedics. Table 2 shows that within the emergency nurses survey, most respondents were registered nurses (50.3%, n = 80), clinical nurse specialists (15.1%, n = 24) and clinical nurse consultants (7.5%, n = 12). A majority of emergency nurses identified that they worked in resuscitation and trauma (76.7%, n = 122), and triage (71.7%, n = 114), respectively, which was followed by 64.2% (n = 102) of respondents working in acute respiratory care. Most emergency physicians identified themselves as senior Fellows of ACEM (FACEM) who were more than ten years post-fellowship (43.6%, n = 48), FACEMs who were less than ten years post-fellowship (37.3%, n = 41), and advanced trainees (11.8%, n = 13). The majority of respondents from the paramedic survey indicated that they were paramedics (39.1%, n = 63), intensive care paramedics (31.7%, n = 51) and advanced care paramedics (21.7%, n = 35).

Table 2.

Current positions and/or level of certification of respondents.

| Emergency nurses |

Emergency physicians |

Paramedics |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Nursing unit manager | 5 | 3.1 | Senior FACEM | 48 | 43.6 | Intensive care paramedic | 51 | 31.7 |

| Nurse practitioner | 7 | 4.4 | FACEM | 41 | 37.3 | Advanced care paramedic | 35 | 21.7 |

| Nurse manager | 7 | 4.4 | Advanced trainee | 13 | 11.8 | Paramedic | 63 | 39.1 |

| Clinical nurse educator | 8 | 5 | Provisional trainee | 3 | 2.7 | Trainee paramedic | 7 | 4.3 |

| Clinical nurse consultant | 12 | 7.5 | Other | 5 | 4.5 | Patient Transport Officer | 0 | 0 |

| Clinical nurse specialist | 24 | 15.1 | Other | 5 | 3.1 | |||

| Registered nurse | 80 | 50.3 | ||||||

| Enrolled nurse | 5 | 3.1 | ||||||

| Other | 11 | 6.9 | ||||||

FACEM = Fellow of Australasian College for Emergency Medicine.

3.2. Knowledge

When asked to rate their knowledge of COVID-19 (i.e. knowledge at the time of completing the survey), a majority of respondents selected ‘good’ (EN: 51.6%, n = 82; EP: 39.1%, n = 43; PARA: 49.7%, n = 80) and ‘very good’ (EN: 26.4%, n = 42; EP: 28.2%, n = 31; PARA: 28.6%, n = 46).

Respondents were asked where they went for up-to-date information about COVID-19 (Table 3 ). State or territory department of health websites was reported as the main source of information for emergency nurses (78%, n = 124), emergency physicians (78.2%, n = 86) and paramedics (68.9%, n = 111). Information from colleagues was the second most accessed source for emergency nurses (37.1%, n = 50) and emergency physicians (64.5%, n = 71). On the other hand, for paramedics, their respective state organisation's (e.g. NSW Ambulance or Ambulance Victoria) emails (65.2%, n = 105) were the second most accessed sources of information. In addition, the majority of paramedics (70.2%, n = 113) indicated that their state/territory ambulance service communicated with them on a daily basis in regards to COVID-19 information. About one-third of respondents from emergency nurses (31.4%, n = 50) and emergency physicians (38.2%, n = 42) stated that they visited CENA and ACEM websites, respectively, for information. However, the ACP website was used by 16.8% of paramedics (n = 27). Less commonly used sources of information across the three professional groups included advice from the Australian Government Health Protection Principal Committee and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention websites. Other sources of information accessed by respondents are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sources of information about COVID-19.

| Source of information | Emergency nurses |

Emergency physicians |

Paramedics |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Commonwealth Department of Health website | 50 | 31.4 | 25 | 22.7 | 54 | 33.5 |

| State/territory departments of health website | 124 | 78 | 86 | 78.2 | 111 | 68.9 |

| Australia Government Health Protection Principal Committee | 16 | 10.1 | 10 | 9.1 | 19 | 11.8 |

| Communicable Diseases Network Australia (CDNA) Guidelines | 16 | 10.1 | 20 | 18.2 | 12 | 7.5 |

| National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce | 52 | 32.7 | 39 | 35.5 | 13 | 8.1 |

| 2019 Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare | 31 | 19.5 | 12 | 10.9 | 17 | 10.6 |

| CENA/ACEM/ACP website | 50 | 31.4 | 42 | 38.2 | 27 | 16.8 |

| Own organisation websitea | N/A | N/A | 91 | 56.5 | ||

| Own organisation emaila | N/A | N/A | 105 | 65.2 | ||

| US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | 9 | 5.7 | 14 | 12.7 | 10 | 6.2 |

| World Health Organization | 57 | 35.8 | 28 | 25.5 | 60 | 37.3 |

| Colleagues | 59 | 37.1 | 71 | 64.5 | 30 | 18.6 |

| Social media (e.g. Twitter and Facebook) | 28 | 17.6 | 39 | 35.5 | 26 | 16.1 |

| Scientific literature and journals | 42 | 26.4 | 63 | 57.3 | 38 | 23.6 |

| Television, radio or newspaper | 34 | 21.4 | 29 | 26.4 | 29 | 18 |

| Other | 28 | 17.6 | 19 | 17.3 | 7 | 4.3 |

CENA = College of Emergency Nurses Australasia; ACEM = Australasian College for Emergency Medicine; ACP = Australasian College of Paramedicine.

Within ACP, there are individual state/territory organisational branches. These jurisdictions provided information via their organisation websites and emails.

Respondents were asked how easy it was to keep up to date with the constantly evolving 11 categories of information about COVID-19 (Table 4 ). For both emergency nurses and physicians, the top three categories that respondents stated were ‘easy’ and ‘very easy’ to follow and keep-up-to-date with were: a) ‘epidemiology e.g. case numbers and location’ (EN: 70.5%, n = 112; EP: 75.5%, n = 83); b) ‘clinical presentation e.g. signs and symptoms’ (EN: 68.5%, n = 108; EP: 64.5%, n = 71); and c) ‘use of PPE’ (EN: 65.4%, n = 104; EP: 54.5%, n = 60). For paramedics, the top three categories that respondents stated were ‘easy’ and ‘very easy’ to follow and keep-up-to-date with were: a) ‘epidemiology’ (71.5%, n = 115); b) ‘infection prevention and control measures’ (68.3%, n = 110); and c) ‘use of PPE’ (65.8%, n = 106). ‘Case definition’ for COVID-19 was reported as the most difficult category for all three emergency clinician groups to stay on top of, with approximately one-third of respondents from each group stating that it was ‘difficult to very difficult’ to keep up to date with changing guidelines (EN: 27%, n = 43; EP: 31.8%, n = 35; PARA: 32.9%, n = 53). Other categories that the respondents found ‘difficult to very difficult’ to keep up to date with included ‘contact tracing’ (all three groups), ‘infection prevention and control measures’ (mostly emergency physicians), ‘treatment and management of patients’ (mostly emergency nurses), ‘laboratory testing’ and ‘clinical presentation’ (both categories mostly paramedics).

Table 4.

Ease of keeping up-to-date with 11 categories of COVID-19 information.

| Categories | Very difficult |

Difficult |

Neutral |

Easy |

Very easy |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Case definition | EN | 5 | 3.1 | 38 | 23.9 | 39 | 24.5 | 66 | 41.5 | 11 | 6.9 |

| EP | 5 | 4.5 | 30 | 27.3 | 28 | 35.5 | 35 | 31.8 | 12 | 10.9 | |

| PARA | 9 | 5.6 | 44 | 27.3 | 24 | 14.9 | 73 | 45.3 | 11 | 6.8 | |

| Epidemiology | EN | 4 | 2.5 | 17 | 10.7 | 26 | 16.4 | 85 | 53.5 | 27 | 17.0 |

| EP | 4 | 3.6 | 9 | 8.2 | 14 | 12.7 | 55 | 50.0 | 28 | 25.5 | |

| PARA | 2 | 1.2 | 22 | 13.7 | 22 | 13.7 | 88 | 54.7 | 27 | 16.8 | |

| Clinical presentation | EN | 3 | 1.9 | 19 | 11.9 | 28 | 17.6 | 90 | 56.6 | 19 | 11.9 |

| EP | 0 | 0 | 10 | 9.1 | 29 | 26.4 | 58 | 52.7 | 13 | 11.8 | |

| PARA | 3 | 1.9 | 29 | 18.0 | 26 | 16.1 | 81 | 50.3 | 22 | 13.7 | |

| Laboratory testing | EN | 5 | 3.1 | 25 | 15.7 | 56 | 35.2 | 60 | 37.7 | 13 | 8.2 |

| EP | 2 | 1.8 | 21 | 19.1 | 35 | 31.8 | 44 | 40.0 | 8 | 7.3 | |

| PARA | 11 | 6.8 | 24 | 14.9 | 29 | 18.0 | 76 | 47.2 | 21 | 13.0 | |

| IPC measures | EN | 6 | 3.8 | 28 | 17.6 | 28 | 17.6 | 81 | 50.9 | 16 | 10.1 |

| EP | 8 | 7.3 | 23 | 20.9 | 22 | 20.0 | 47 | 42.7 | 10 | 9.1 | |

| PARA | 8 | 5.0 | 19 | 11.8 | 24 | 14.9 | 86 | 53.4 | 24 | 14.9 | |

| Use of PPE | EN | 7 | 4.4 | 28 | 17.6 | 20 | 12.6 | 84 | 52.8 | 20 | 12.6 |

| EP | 14 | 12.7 | 14 | 12.7 | 22 | 20.0 | 48 | 43.6 | 12 | 10.9 | |

| PARA | 6 | 3.7 | 21 | 13.0 | 28 | 17.4 | 80 | 49.7 | 26 | 16.1 | |

| Treatment & management | EN | 3 | 1.9 | 43 | 27.0 | 51 | 32.1 | 54 | 34.0 | 8 | 5.0 |

| EP | 3 | 2.7 | 19 | 17.3 | 35 | 31.8 | 49 | 44.5 | 4 | 3.6 | |

| PARA | 4 | 2.5 | 32 | 19.9 | 46 | 28.6 | 66 | 41.0 | 13 | 8.1 | |

| Isolation practices | EN | 9 | 5.7 | 31 | 19.5 | 26 | 16.4 | 80 | 50.3 | 12 | 7.5 |

| EP | 10 | 9.1 | 23 | 20.9 | 23 | 20.9 | 47 | 42.7 | 7 | 6.4 | |

| PARA | 7 | 4.3 | 32 | 19.9 | 46 | 28.6 | 66 | 41.0 | 13 | 8.1 | |

| Contact tracing | EN | 5 | 3.1 | 38 | 23.9 | 71 | 44.7 | 41 | 25.8 | 4 | 2.5 |

| EP | 14 | 12.7 | 27 | 24.5 | 41 | 37.3 | 25 | 22.7 | 3 | 2.7 | |

| PARA | 12 | 7.5 | 41 | 25.5 | 65 | 40.4 | 35 | 21.7 | 8 | 5.0 | |

| Travel advice & restrictions | EN | 3 | 1.9 | 23 | 14.5 | 35 | 22.0 | 79 | 49.7 | 19 | 11.9 |

| EP | 3 | 2.7 | 20 | 18.2 | 32 | 29.1 | 47 | 42.7 | 8 | 7.3 | |

| PARA | 5 | 3.1 | 22 | 13.7 | 38 | 23.6 | 79 | 49.1 | 17 | 10.6 | |

| Public health orders | EN | 3 | 1.9 | 21 | 13.2 | 43 | 27.0 | 77 | 48.4 | 15 | 9.4 |

| EP | 8 | 7.3 | 21 | 19.1 | 27 | 24.5 | 43 | 39.1 | 11 | 10.0 | |

| PARA | 5 | 3.1 | 26 | 16.1 | 43 | 26.7 | 69 | 42.9 | 18 | 11.2 | |

EN = emergency nurse; EP = emergency physician; PARA = paramedic; IPC = infection prevention and control; PPE = personal protective equipment.

3.3. Preparedness

A majority of respondents across each emergency clinician group stated that they were not a member of a COVID-19 committee (EN: 78.6%, n = 125; EP: 60.9%, n = 67; PARA: 88.8%, n = 143). However, for those who indicated that they were part of a COVID-19 committee, it was mainly at the hospital level for emergency nurses and physicians (EN: 19.5%, n = 31; EP: 32.7%, n = 36) or at an organisational level for paramedics (8.7%, n = 14).

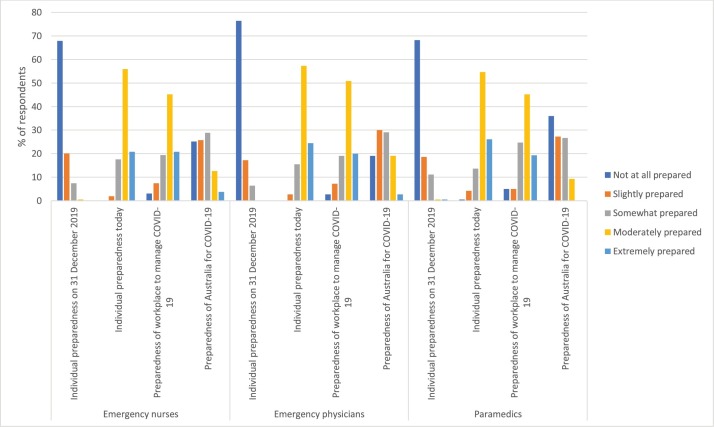

Respondents reported varying levels of preparedness for COVID-19 at an individual, workplace and/or national level (Fig. 1 ). On an individual level, a majority of respondents across each group (EN: 67.9%, n = 108; EP: 76.4%, n = 84; PARA: 68.3%, n = 110) indicated that they were ‘not at all prepared’ for COVID-19 on 31 December 2019, the date when the World Health Organization was formally notified about the initial cluster of cases in Wuhan, China [23]. At the time of completing the survey (i.e. preparedness today), approximately 80% of respondents across each group stated that they felt ‘moderately to extremely prepared’ (EN: 76.8%, n = 122; EP: 81.8%, n = 90; PARA: 80.8%, n = 130). Similarly, at a workplace level, around half of respondents across each group stated that their workplace/organisation was ‘moderately prepared’ (EN: 45.3%, n = 72; EP: 50.9%, n = 56; PARA: 45.3%, n = 73). Only around 10% of respondents indicated that their workplace was ‘slightly to not at all prepared’ (EN: 10.6%, n = 17; EP: 10%, n = 11; PARA: 10%, n = 16). In contrast, when it came to Australia's preparedness for COVID-19, 63.3% of paramedics (n = 102) reported that the nation was ‘slightly to not at all prepared’. This opinion was echoed by emergency nurses and emergency physicians, with 51% (n = 81) and 49.1% (n = 54) respectively, selecting the same range for Australia's COVID-19 preparedness.

Fig. 1.

Preparedness for COVID-19 on an individual, workplace and national level.

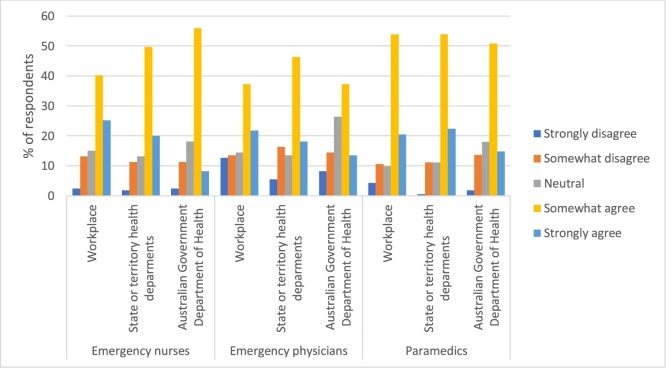

Respondents were asked about how clear and timely communication on COVID-19 was during the pandemic (Fig. 2 ). The majority in all three groups that they ‘somewhat to strongly agreed’ that their respective state/territory department of health (EN: 69.8%, n = 111; EP: 64.6%, n = 71; PARA: 76.4%, n = 123) provided clear, timely and authoritative information about COVID-19. Almost three-quarters of paramedics (74.5%, n = 120) ‘somewhat to strongly agreed’ that their workplace/organisation provided clear, timely and authoritative information about COVID-19. On the other hand, it was noted that 12.7% of emergency physicians (n = 14) respondents reported that they ‘strongly disagreed’ that their workplace provided clear, timely and authoritative information about COVID-19.

Fig. 2.

Respondents’ perceptions of the timeliness and clarity of communication from their workplace/organisation and federal and state/territory government departments of health.

When asked if their workplace/organisation had COVID-19 guidelines and an outbreak response plan in place, most respondents selected ‘yes’ (EN: 71.7%, n = 114; EP: 84.5%, n = 93; PARA: 72.7%, n = 117). Of these respondents, the majority for each emergency clinician group stated that they were ‘mostly familiar’ (EN: 30.8%, n = 49; EP: 42.7%, n = 47; PARA = 29.2%, n = 47) with these guidelines and plans. Each group separately indicated that they felt the guidelines were mostly ‘easy’ or ‘neutral’ to follow. However, it was observed that over 20% of respondents from the emergency nurses (22.6%, n = 36) and paramedics (24.2%, n = 39) groups ‘don’t know’ if their workplace/organisation have these guidelines or plans. Just over 10% of emergency physicians (11.8%, n = 13) indicated ‘don’t know’ as well.

In terms of COVID-19 education, training, or instruction within the workplace, 86.2% of emergency nurses (n = 137), 86.4% of emergency physicians (n = 95), 77.6% of paramedics (n = 125) stated that they had received a form of one or the other. Of these, the majority indicated that the training received was ‘mostly adequate’ (EN: 45.3%, n = 72; EP: 51.8%, n = 57; PARA: 37.3%, n = 60). It was noted that the bulk of training received was provided internally. Emergency nurses were asked about six types of COVID-19 specific training (Table 5 ). The top two types of training that respondents indicated they had received from their unit/department were ‘Alterations to procedures in suspected/confirmed COVID-19 patients’ (90.6%, n = 144) and ‘Patient workflow and segregation of patients’ (88.7%, n = 141). Our findings show that almost all emergency nurses (86.2%, n = 137) and emergency physicians (91.8%, n = 101) respondents reported having received training or certification in the use of PPE for managing patients with COVID-19. Whilst a majority of paramedics indicated having also received PPE training, 20.5% of this cohort (n = 33) stated that they had not. Table 6 shows that of those respondents who had received PPE training, most rated the training to be ‘mostly adequate’ (EN: 53.3%, n = 73; EP: 45.5%, n = 50; PARA: 37.3%, n = 60). When asked how confident they felt in using PPE to manage and treat patients with suspected/confirmed COVID-19, approximately half of the respondents from each emergency clinician group indicated that they were ‘mostly confident’. Emergency nurses were also satisfied with the availability of PPE at their workplace, with 93% (n = 148) reporting that PPE was ‘generally to always available’. Only 3.1% (n = 5) of emergency nurses reported that PPE was ‘sometimes available’ at their workplace. None reported that PPE was ‘rarely available’.

Table 5.

Types of COVID-19 specific education, training and instruction received by emergency nurses at their workplace.

| Yes – received education/training/instruction |

||

|---|---|---|

| % | n | |

| Alterations to procedures in suspected/confirmed COVID-19 patients (e.g. aerosolising procedures) | 90.6 | 144 |

| Patient workflow and segregation of patients | 88.7 | 141 |

| Screening for COVID-19 | 85.5 | 136 |

| Patient care for suspected/confirmed COVID-19 patients | 84.9 | 135 |

| New COVID-19 workplace guidelines and policies | 84.3 | 134 |

| Use of screening criteria to triage COVID-19 patients | 83.6 | 133 |

Table 6.

Adequacy of PPE training and how confident respondents feel using PPE to treat COVID-19 patients.

| Emergency nurses |

Emergency physicians |

Paramedics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Adequacy of PPE training | ||||||

| Not at all adequate | 1 | 0.7 | 3 | 2.7 | 3 | 1.9 |

| Slightly adequate | 10 | 7.3 | 10 | 9.1 | 15 | 9.3 |

| Somewhat adequate | 22 | 16.1 | 15 | 13.6 | 30 | 18.6 |

| Mostly adequate | 73 | 53.3 | 50 | 45.5 | 60 | 37.3 |

| Entirely adequate | 31 | 22.6 | 23 | 20.9 | 19 | 11.8 |

| Confidence in using PPE | ||||||

| Not at all confident | 1 | 0.6 | 3 | 2.7 | 4 | 2.5 |

| Slightly confident | 10 | 6.3 | 10 | 9.1 | 12 | 7.5 |

| Somewhat confident | 18 | 11.3 | 10 | 9.1 | 32 | 19.9 |

| Mostly confident | 77 | 48.4 | 59 | 53.9 | 79 | 49.1 |

| Entirely confident | 47 | 29.6 | 28 | 25.5 | 33 | 20.5 |

3.4. Experiences

Almost all emergency nurses and emergency physicians indicated that their organisation was involved in assessing suspected cases of COVID-19 (EN: 94.5%, n = 104; EP: 91.8%, n = 146) and treating and managing confirmed COVID-19 cases (EN: 88.7%, n = 141; EP: 89.1%, n = 98). On the other hand, 71.4% of paramedics (n = 115) stated that their organisation referred suspected/confirmed COVID-19 cases. When asked if they had been re-deployed away from frontline work during the outbreak, 80.7% of paramedics (n = 130) selected ‘no’. The majority of respondents across all three emergency clinician groups reported that they had been directly involved in managing a patient with suspected/confirmed COVID-19 (EN: 70.4%, n = 112; EP: 80%, n = 88; PARA: 69.6%, n = 112). Over half of paramedics (53.4%, n = 86) indicated that it was ‘difficult to very difficult’ to clean the ambulance after transporting a COVID-19 positive patient.

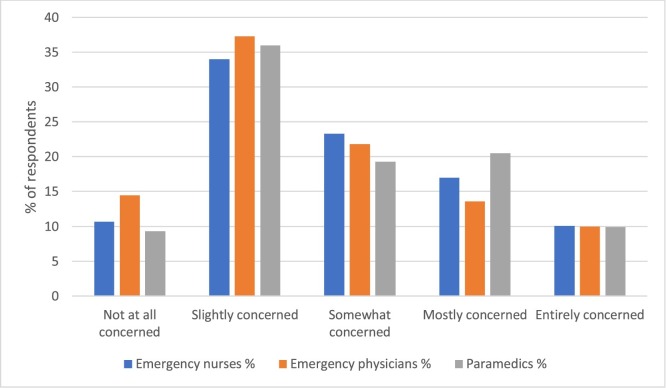

When respondents were asked about their concerns about contracting SARS-CoV-2 at work, over half of respondents for each group expressed that they were ‘slightly to somewhat concerned’ (Fig. 3 ). It was noted that, on average, approximately 10% of respondents from each group indicated that they were as equally ‘not at all concerned’ as they were ‘extremely concerned’ about the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to them.

Fig. 3.

Respondents’ concerns about contracting SARS-CoV-2 at workplace.

However, when it came to taking annual leave due to concerns about COVID-19, around 80–90% of respondents from each emergency clinician group stated that they had not taken any annual leave (EN: 91.8%, n = 146; EP: 91.8%, n = 106; PARA: 88.8%, n = 143) or sick leave (EN: 89.3%, n = 142; EP: 90%, n = 99; PARA: 83.9%, n = 135) during this time.

The majority of respondents from each group responded ‘no’ to two questions pertaining to a) if they have avoided telling people about caring for COVID-19 patients due to potential negative reactions (EN: 54.7%, n = 87; EP: 70.9%, n = 78; PARA: 62.7%, n = 101) and b) have their family or friends avoided contact due to the nature of their work (EN: 54.7%, n = 87; EP: 56.4%, n = 62; PARA: 64%, n = 103). Our findings also showed that approximately 20% of respondents across each group indicated that they had experienced or witnessed racial or other forms of discrimination at work due to the COVID-19 outbreak (EN: 22%, n = 35; EP: 18.2%, n = 20; PARA: 20.5%, n = 33).

For emergency nurses and emergency physicians, over half of the respondents in each group indicated that their workload had ‘moderately to considerably increased’ due to COVID-19 (Table 7 ). It was further noted that 18.2% (n = 20) of emergency physicians respondents stated that their workload had ‘lessened’. This was echoed in the paramedics group, with 32.9% (n = 53) of respondents reporting that their workload has also ‘lessened’. These results were reflected when respondents were asked if they felt more stressed at work due to COVID-19. The majority of emergency nurses (71.1%, n = 113) and emergency physicians (68.2%, n = 75) expressed that they were ‘slightly to moderately stressed’ at work. On the other hand, the majority of paramedics (67.1%, n = 108) said that they were ‘somewhat to not at all stressed’ due to the impact of COVID-19 at work. When asked if their workplace provided staff debriefings and other psychological support services, most respondents from each emergency clinician group indicated that their workplace provided both services (EN: 40.9%, n = 65; EP: 47.3%, n = 52; PARA: 50.9%, n = 82). Approximately 10% of respondents from each group stated that their workplace provided neither and around 20–25% of respondents from each group reported that they do not know if their workplace provided these services (Table 8 ). For each group, the majority of respondents reported never having attended a staff debriefing (EN: 66%, n = 105; EP: 70%, n = 77; PARA: 78.3%, n = 126). For those respondents who had attended a staff debriefing, our findings show that they found it to be ‘slightly to moderately useful’ (EN: 23.9%, n = 38; EP: 22.7%, n = 25; PARA: 13.1%, n = 21). Almost all respondents across each group reported never accessing their workplace's psychological support services (EN: 93.1%, n = 148; EP: 92.2%, n = 102; PARA: 88.8%, n = 142).

Table 7.

Impact of COVID-19 on respondents’ workload and stress.

| Emergency nurses |

Emergency physicians |

Paramedics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Workload due to COVID-19 | ||||||

| No, it has lessened | 7 | 4.4 | 20 | 18.2 | 53 | 32.9 |

| No, it has stayed the same | 8 | 5 | 6 | 5.5 | 11 | 6.8 |

| Slightly more | 17 | 10.7 | 9 | 8.2 | 17 | 10.6 |

| Somewhat more | 22 | 13.8 | 14 | 12.7 | 28 | 17.4 |

| Moderately more | 33 | 20.8 | 18 | 16.4 | 16 | 9.9 |

| Considerably more | 64 | 40.3 | 40 | 36.4 | 28 | 17.4 |

| Stress at work due to COVID-19 | ||||||

| Not at all | 14 | 8.8 | 13 | 11.8 | 33 | 20.5 |

| Slightly | 34 | 21.4 | 17 | 15.5 | 38 | 23.6 |

| Somewhat | 37 | 23.3 | 21 | 19.1 | 37 | 23 |

| Moderately | 42 | 26.4 | 37 | 33.6 | 30 | 18.6 |

| Extremely | 24 | 15.1 | 19 | 17.3 | 15 | 9.3 |

Table 8.

Support services provided by respondents’ workplace.

| Emergency nurses |

Emergency physicians |

Paramedics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Yes, debriefing only | 7 | 4.4 | 2 | 1.8 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Yes, staff psychological support only | 22 | 13.8 | 13 | 11.8 | 27 | 16.8 |

| Yes, both | 65 | 40.9 | 52 | 47.3 | 82 | 50.9 |

| Neither | 17 | 10.7 | 10 | 9.1 | 16 | 9.9 |

| Don’t know | 40 | 25.2 | 30 | 27.3 | 26 | 16.1 |

We asked respondents to tell us the ‘single biggest issue about COVID-19’. We received 143 responses from emergency nurses, 106 responses from emergency physicians and 150 responses from paramedics. Respondents’ free text comments largely fell into nine different categories (Table 9 ). For emergency nurses and physicians, their biggest challenge was around changes to workflow processes in the ED and the difficulty in isolating COVID-19 patients (EN: 21 responses; EP: 17 responses), as illustrated by the following quote:

“Lack of appropriate space to ensure isolation” (Respondent 112 – emergency nurse)

Table 9.

Respondents’ comments on the biggest single challenge about COVID-19.

| Category | Emergency nurses | Emergency physicians | Paramedics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public complacency | “People in the community not taking restrictions seriously” (Respondent 3) | “Ignorance of the general public” (Respondent 1) | “People not following the guidelines” (Respondent 61) |

| “Complacency as we have avoided the worst of the first wave” (Respondent 28) | “Concern about complacency” (Respondent 60) | “Public fatigue regarding COVID-19” (Respondent 108) | |

| Inconsistent and rapidly changing information | “Discrepancy between directions provided by the ‘COVID team’ and our team leaders” (Respondent 12) | “Challenge of navigating inconsistent/rapidly changing advice in a high scrutiny environment (Respondent 72) | “Unclear, ever-changing guidelines” (Respondent 60) |

| “Constantly changing information and situation” (Respondent 37) | “Confusion surrounding rapidly changing policies and practices” (Respondent 98) | “Stress of keeping up-to-date with the constant change in policy, procedure, guidelines (Respondent 133) | |

| Lack of communication | “Changes imposed on work practice without effective communication. We are not given the opportunity to give feedback on any changes” (Respondent 46) | “Receiving clear communication about how to manage the outbreak” (Respondent 28) | “Not getting enough information, not getting the right information” (Respondent 42) |

| “We never get told anything about planning until the moment it happens” (Respondent 35) | “Lack of clear written communication about rapidly changing guidelines” (Respondent 100) | “Trying to get a consensus/consistent approach from the doctors in our workplace” (Respondent 76) | |

| Lack of plan | “The under-preparedness of health resources” (Respondent 48) | “It has highlighted pre-existing stresses in the health system” (Respondent 19) | “Reality checks for organisation” (Respondent 12) |

| “We are not prepared and not enough manpower” (Respondent 50) | “We were under prepared nationally” (Respondent 85) | “Lacklustre response of the government as a whole” (Respondent 16) | |

| Workflow management (e.g. changes and issues) | “Correctly streaming/identifying and then placing patient in the appropriate location” (Respondent 92) | “Balance between infection control mitigation strategies and providing overall patient care to the (current) vast majority of patients without COVID-19 (Respondent 7) | “All the changes to operating procedures” (Respondent 27) |

| “Lack of appropriate space to ensure isolation” (Respondent 112) | “ED design not adequate for infection control” (Respondent 54) | “Expectation that we will rush into a home and not protect ourselves when everyone else is advised to keep a social distance” (Respondent 95) | |

| Changes to staffing and workload | “Adequate staffing and training” (Respondent 49) | “Workload and the system's ability to cope. Caring for my staff” (Respondent 26) | “Doubling of my workload with no additional staffing assistance” (Respondent 131) |

| “The constant anxiety and increased workload around every presentation” (Respondent 68) | “Other hospitals closing and the increased workload” (Respondent 39) | “Workload for managers and support staff who are developing and rolling our procedures” (Respondent 147) | |

| PPE issues (e.g. availability and quality) | “Not enough PPE or sanitiser readily available” (Respondent 84) | “Inadequate PPE right from the start” (Respondent 32) | “No fit testing of PPE” (Respondent 13) |

| “Lack of access to and knowledge surrounding use of PPE” (Respondent 127) | “Confusion over level of PPE recommended” (Respondent 44) | “Struggle to obtain sufficient PPE” (Respondent 29) | |

| The ‘unknown’ | “Unpredictability” (Respondent 74) | “Uncertainty” (Respondent 34) | “Uncertainty” (Respondent 11) |

| “Wondering when it will end” (Respondent 124) | “Unpredictable course, makes it hard to plan both at work and in personal life” (Respondent 95) | “Uncertainty of the future” (Respondent 146) | |

| Concern about self/family | “Passing on illnesses to my family” (Respondent 83) | “Risk to elderly relatives” (Respondent 13) | “Contracting diseases and passing it to others” (Respondent 59) |

| “I can’t travel home…my mental health is not great” (Respondent 132) | “Getting infected from carriers with no symptoms” (Respondent 18) | “The social isolation” (Respondent 145) | |

For paramedics, their biggest challenge was the availability and quality of PPE (27 responses), which was also reflected in the responses received from the emergency nurses and physicians (EN: 11 responses; EP: 14 responses):

“No fit testing of PPE” (Respondent 13 - paramedic)

“Inadequate PPE right from the start” (Respondent 32 – emergency physician)

There were six responses from paramedics regarding the difficulty in cleaning the ambulance during shifts and between patients, as stated in the following quotes:

“Not being able to trust if other colleagues have adequately cleaned the ambulance including the front cabin” (Respondent 32 – paramedic)

“Cleaning ambulance and ambulance equipment is fatiguing” (Respondent 70 – paramedic)

Concern about contracting the virus and spreading it to family and friends was a top issue for each group (EN: 16 responses; EP: 13 responses; PARA: 17 responses), as described by the following respondents:

“Passing on illnesses to my family” (Respondent 83 – emergency nurse)

“Getting infected from carriers with no symptoms” (Respondent 18 – emergency physician)

Two other highly reported issues were the complacency of the general public (EN: 19 responses; EP: 3 responses; PARA: 15 responses) and the inconsistent and rapidly changing information, which resulted in confusion, stress and mistrust (EN: 16 responses; EP: 10 responses; PARA: 19 responses).

4. Discussion

This study examined the knowledge, preparedness and experiences of emergency nurses, emergency physicians and paramedics in Australian healthcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. We report challenges experienced by these emergency clinicians and note that supporting acute care healthcare workers during a global pandemic is multifactorial and support of physical and mental well-being is essential to an effective pandemic response [24], [25], [26].

As an emerging and novel disease, the COVID-19 situation continues to evolve on a rapid scale as more information comes to light. As such, it is essential for emergency clinicians to have accurate and up-to-date information. The top source of information for respondents in our study was state and territory department of health websites, which are readily accessible to the public and updated daily with the latest information and guidelines [27], [28], [29], [30]. Studies have shown that healthcare workers feel better prepared for pandemics if they are able to access up-to-date, consistent and clear information [31], [32]. It was noted from our study that if information was inconsistent and unclear, it resulted in stress, confusion and mistrust.

Preparedness is key to minimising the impact of pandemics and large-scale public health emergencies on patients, healthcare workers and healthcare systems. As such, it is vital to have emergency and disaster management response plans in place. The Australian Government's Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) was activated on the 27 February 2020 [5], followed by the Coronavirus (COVID-19) National Health Plan, which was rolled out on 11 March 2020 [33], [34]. The National Health Plan included funding and support across primary care and aged care sectors, hospitals, research, training programs, communication campaigns, and the national medical stockpile (including PPE supplies). The majority of respondents in our study indicated that their workplace/organisation had a COVID-19 response plan in place. However, without regular testing of these pandemic response plans, their effectiveness reduces, as reported by a study following the H1N1 influenza pandemic in Victoria [35]. Studies have reported that extensive and regular training for pandemics (e.g. mandatory yearly competency-based training and education programs with skill based drills) would enable nurses and paramedics to feel more prepared and confident in their abilities in care for patients [36], [37], [38], [39]. In addition, clear leadership and clear directives from management early on in the pandemic is critical to preparedness and planning [40], [41]. Respondents in our study reported that inconsistent and rapidly changing information, coupled with a lack of preparation, communication and clear guidance from management were significant challenges, resulting in mistrust and a lack of confidence in the healthcare system.

Our findings demonstrated that there were several concerns raised by the respondents that impacted their experiences during COVID-19. Fears about contracting the virus and passing it onto family was a common concern raised by respondents in our study. SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to be predominately spread via direct, indirect or close contact with infected respiratory droplets [42], [43]. To protect and limit the spread and transmission of COVID-19 to healthcare workers, appropriate usage of PPE has been strongly recommended and encouraged [44], [45]. Following the ‘second wave’ of COVID-19 in Victoria, Australia, it was reported that approximately 17.6% of the COVID-19 cases in Victoria were linked to healthcare workers [46]. Availability of and access to PPE stockpiles has been a critical issue throughout the COVID-19 pandemic [15], [47], [48], [49], [50] and this was also a major concern for the respondents in our study with mentions of PPE being either inadequate or not readily accessible.

Workflow management in the ED was a top challenge and concern for emergency nurses and physicians in our study, in that the structure and layout of the EDs made it extremely difficult to isolate suspected/confirmed COVID-19 patients from other non-COVID-19 patients. This was a source of increased stress and anxiety for the emergency nurses and physicians. Emergency department overcrowding, including a lack of appropriate space to treat patients, was identified as significant markers of stress for emergency clinicians during the 2009 influenza H1N1 pandemic in Australia [11]. Hospitals, especially EDs, must find practical strategies to manage potential surge during outbreaks and prevent further transmission [51]. Following the MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea, several strategies were immediately implemented and then used to manage the COVID-19 outbreak and prevent further transmission [52]. These strategies included dedicated COVID-19 task forces, hospitals, community facilities, emergency centres, and cohorting and treating patients with respiratory symptoms away from those without any. Other suggestions have included the establishment of fever and isolation zones and increased access to telehealth [53].

About one-third of paramedics and 20% of emergency physicians reported that their workload had lessened. During the quarantine period and peak of the first-wave in Australia in late March – early April 2020, the number of ambulance call-outs dropped across most Australian states and territories [54]. A UK study reported that ambulance transports to the accident and emergency department fell 29% from April 2019 to April 2020 [55]. This could be attributed to either fear of visiting an ED and deciding to delay treatment or that individuals were simply restricted to their homes during quarantine. It has also been reported that fear and loss of trust in the health system resulted in reduced visits to healthcare facilities during the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Sierra Leone [8]. The Australian government has responded to decreased hospital presentations by pledging increased funding towards telehealth services and home delivery of medicines to allow vulnerable individuals to access medical services but also reduce risk of exposure to COVID-19 [56]. During the COVID-19 State of Emergency restrictions over March – April 2020 in Victoria, presentations to two urban EDs in Melbourne fell by 37.3% [57]. A U.S study found that ED visits declined approximately 40% during March – April 2020 when compared to the previous year [58] and another study found that 41% of U.S. adults delayed treatment or avoided medical care due to concerns about COVID-19 [59]. Similarly, the admission and consultation of high acuity care stroke patients pre-COVID-19 and during the pandemic was reported to have decreased by approximately 40% [60], [61]. The full impact of delay in seeking emergency care for high acuity care patients is not yet known. Reports have called for increased public health awareness campaigns to educate the public about the importance of seeking appropriate medical care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Frontline healthcare workers who are directly treating COVID-19 patients have been reported to be at higher risk for depression, anxiety, insomnia and distress [62], [63], [64]. To support healthcare workers, many facilities have now initiated staff debriefings and are offering other psychological support services. During the Ebola virus disease outbreak, it was reported that provision of staff debriefings and other support services was critical for the safety and well-being of staff and helped to reduce distress and anxiety [65], [66]. While the majority of respondents in our study did not use these services, a handful from each emergency clinician group did state that they found the staff debriefings to be ‘slightly to moderately useful’. Our findings support international calls for sustained mental health services for healthcare workers during pandemics [67], [68]. However, questions about the effectiveness and utility of clinical debriefings have been raised. A recent systematic review reported that due to factors, including lack of time, informal debriefing with family and friends was found to be useful for paramedics outside of work settings [69]. During a period of promotion for ‘hot debriefs’ following cardiac arrest incidents in an Irish emergency department, the authors found that staff appreciated debriefing as a helpful tool for quality improvement and quality of patient care. However, it was noted that it was difficult to maintain high and consistent participation rates due to unawareness and/or forgetfulness [70]. A survey of US emergency medicine training program leaders found that barriers to debriefing of paediatric critical events included timing and scheduling of the clinical debrief [71]. Further evidence-based interventions on staff perceptions about debriefing is needed. However, it is essential that healthcare facilities continue to actively promote these services to their staff through their official channels.

The low response rates are a limitation of this study. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study that describes the knowledge, preparedness and experiences of three individual emergency clinician groups during COVID-19 in Australian healthcare settings. As such, findings from this study contribute important information to the global reporting of frontline healthcare workers’ experiences during a large-scale infectious diseases outbreak. As the surveys were deployed between June-September 2020, this study does not capture the changing experiences of these emergency clinicians throughout the different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Scale reliability was not undertaken in this study but is recommended for follow-up studies of a similar nature and design. Future studies using a longitudinal design or a qualitative approach would provide an in-depth understanding of the experiences of emergency clinicians during COVID-19.

5. Conclusion

Findings from this study indicate that due to extensive COVID-19 specific training and education and adequate support, emergency clinicians in Australia felt prepared to manage and treat patients during COVID-19. However, significant challenges included inconsistent messaging and lack of clear communications from management, the quality and availability of PPE, and concern about transmission of the disease to family members. It is essential that Australian healthcare facilities continue to provide appropriate and adequate support services to improve safety and well-being for emergency clinicians.

Conflict of interest

RZS is Editor-in-Chief, MF and JC are senior editors, KC is an associate editor and BD is a member of the AUEC International Editorial Advisory Board. All were blinded to the submission in the journal's editorial management system, and none had any role to play in the peer review or editorial decision-making process whatsoever. An Acting Editor-in-Chief was appointed to manage this paper. There were no other conflicts of interest declared from the authors.

Authors’ contributions

RZS conceived and designed the study. CL, CS, SN and RZS drafted the study protocol. All authors designed and tested the survey instruments. CL, CS, SN and RZS supervised data collection and curation. All authors analysed and interpreted the data. CL and RZS wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. All authors approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was an investigator-initiated research project and did not receive financial support from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to all the emergency nurses, emergency physicians and paramedics for taking the time to complete the survey. We thank Dr Keren Kaufman-Francis for her assistance with this study. We also thank the College of Emergency Nursing Australasia, The Australasian College for Emergency Medicine and The Australasian College of Paramedicine for their support of this study and their assistance in distributing the survey to their members.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.auec.2021.03.008.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bloom D.E., Cadarette D. Infectious disease threats in the twenty-first century: strengthening the global response. Front Immunol. 2019;10:549. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caly L., Druce J., Roberts J. Isolation and rapid sharing of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) from the first patient diagnosed with COVID-19 in Australia. Med J Aust. 2020;212(10):459–462. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaban R.Z., Li C., O'Sullivan M.V.N. COVID-19 in Australia: our national response to the first cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the early biocontainment phase. Int Med J. 2020 doi: 10.1111/imj.15105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desborough J., Hall Dykgraaf S., de Toca L. Australia's national COVID-19 primary care response. Med J Aust. 2020;213(3) doi: 10.5694/mja2.50693. 104–6 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health . In: Australian health sector emergency response plan for novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Department of Health, editor. Commonwealth of Australia; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Man C.Y., Yeung R.S., Chung J.Y. Impact of SARS on an emergency department in Hong Kong. Emerg Med (Fremantle) 2003;15(5–6):418–422. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2003.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S.Y., Khang Y.H., Lim H.K. Impact of the 2015 Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak on emergency care utilization and mortality in South Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2019;60(8):796–803. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.8.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elston J.W., Moosa A.J., Moses F. Impact of the Ebola outbreak on health systems and population health in Sierra Leone. J Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38(4):673–678. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rausa E., Kelly M.E., Manfredi R. Impact of COVID-19 on attendances to a major emergency department: an Italian perspective. Int Med J. 2020;50(9):1159–1160. doi: 10.1111/imj.14972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Tan B.Y.Q. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.FitzGerald G., Patrick J.R., Fielding E.L. QUT; 2010. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza outbreak in Australia: impact on emergency departments. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bai Y., Lin C.-C., Lin C.-Y. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(9):1055–1057. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alwidyan M.T., Oteir A.O., Trainor J. Working during pandemic disasters: views and predictors of EMS providers. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam K.K., Hung S.Y. Perceptions of emergency nurses during the human swine influenza outbreak: a qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2013;21(4):240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halcomb E., McInnes S., Williams A. The experiences of primary healthcare nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jnu.12589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foley D.A., Kirk M., Jepp C. COVID-19 and paediatric health services: a survey of paediatric physicians in Australia and New Zealand. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56(8):1219–1224. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foley D.A., Chew R., Raby E. COVID-19 in the pre-pandemic period: a survey of the time commitment and perceptions of infectious diseases physicians in Australia and New Zealand. Int Med J. 2020;50(8):924–930. doi: 10.1111/imj.14941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foley D.A., Tippett E. Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases Clinical Research N. COVID-19 response: the perspectives of infectious diseases physicians and clinical microbiologists. Med J Aust. 2020;213(9) doi: 10.5694/mja2.50810. 431-e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nickell L.A., Crighton E.J., Tracy C.S. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ. 2004;170(5):793–798. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aldrees T., Al Ghobain M., Alenezi A. Medical residents’ attitudes and emotions related to Middle East respiratory syndrome in Saudi Arabia. A cross-sectional study. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(9):942–947. doi: 10.15537/smj.2017.9.20626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan D.J., Braun B., Milstone A.M. Lessons learned from hospital Ebola preparation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(6):627–631. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Pneumonia of unknown cause – China. Disease outbreak news; 2020.

- 24.Poonian J., Walsham N., Kilner T. Managing healthcare worker well-being in an Australian emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Med Australas. 2020;32(4):700–702. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tannenbaum S.I., Traylor A.M., Thomas E.J. Managing teamwork in the face of pandemic: evidence-based tips. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams J.G., Walls R.M. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1439–1440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health N.S.W. 2020. COVID-19 (coronavirus): health protection Australia. Available from: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/covid-19/Pages/default.aspx [updated 08.12.20] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Department of Health and Human Services . 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): Victoria state government. Available from: https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/coronavirus [updated 07.12.20] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Queensland Health . 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): the State of Queensland. Available from: https://www.qld.gov.au/health/conditions/health-alerts/coronavirus-covid-19 [updated 07.12.20] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Premier and Cabinet . 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Tasmanian Government. Available from: https://www.coronavirus.tas.gov.au/ [updated 07.12.20] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halcomb E., Williams A., Ashley C. The support needs of Australian primary health care nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Nurs Manage. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jonm.13108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corley A., Hammond N.E., Fraser J.F. The experiences of health care workers employed in an Australian intensive care unit during the H1N1 Influenza pandemic of 2009: a phenomenological study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(5):577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Department of Health . 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): National Health Plan resources: Australian Government. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/collections/coronavirus-covid-19-national-health-plan-resources [updated 17.06.20]. [Google Scholar]

- 34.$2.4 Billion health plan to fight COVID-19 [press release]. Australian Government, 11/03/2020; 2020. Available from: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/24-billion-health-plan-fight-covid-19.

- 35.Dewar B., Barr I., Robinson P. Hospital capacity and management preparedness for pandemic influenza in Victoria. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38(2):184–190. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pincha Baduge M.S., Morphet J., Moss C. Emergency nurses’ and department preparedness for an Ebola outbreak: a (narrative) literature review. Int Emerg Nurs. 2018;38:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Speroni K.G., Seibert D.J., Mallinson R.K. Nurses’ perceptions on Ebola care in the United States: Part 2. A qualitative analysis. J Nurs Adm. 2015;45(11):544–550. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cavanagh N., Tavares W., Taplin J. A rapid review of pandemic studies in paramedicine. Australas J Paramed. 2020;17 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gershon R.R., Vandelinde N., Magda L.A. Evaluation of a pandemic preparedness training intervention of emergency medical services personnel. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(6):508–511. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00007421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahern S., Loh E. Leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic: building and sustaining trust in times of uncertainty. BMJ Leader. 2020 leader-2020-000271. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nyenswah T., Engineer C.Y., Peters D.H. Leadership in times of crisis: the example of Ebola virus disease in Liberia. Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(3):194–207. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2016.1222793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cevik M., Kuppalli K., Kindrachuk J. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ. 2020;371:m3862. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Lancet Respiratory Medicine COVID-19 transmission-up in the air. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30514-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gordon C., Thompson A. Use of personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Nurs. 2020;29(13):748–752. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2020.29.13.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higginson R., Jones B., Kerr T. Paramedic use of PPE and testing during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Paramed Pract. 2020;12(6):221–225. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coronavirus update for Victoria – 19 November 2020 [press release]. Victoria: Department of Health and Human Services, 19/11/2020; 2020. Available from: https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/coronavirus-update-victoria-19-november-2020.

- 47.Livingston E., Desai A., Berkwits M. Sourcing personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1912–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Z., Liu S., Xiang M. Protecting healthcare personnel from 2019-nCoV infection risks: lessons and suggestions. Front Med. 2020;14(2):229–231. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0765-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cook T.M. Personal protective equipment during the coronavirus disease (COVID) 2019 pandemic – a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(7):920–927. doi: 10.1111/anae.15071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arnetz J.E., Goetz C.M., Arnetz B.B. Nurse reports of stressful situations during the COVID-19 pandemic: qualitative analysis of survey responses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whiteside T., Kane E., Aljohani B. Redesigning emergency department operations amidst a viral pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1448–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Her M. Repurposing and reshaping of hospitals during the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea. One Health. 2020;10:100137. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mazurik L., Javidan A.P., Higginson I. Early lessons from COVID-19 that may reduce future emergency department crowding. Emerg Med Australas. 2020;32(6):1077–1079. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts L., Heaney C. 2020. Coronavirus has changed the workload of paramedics across Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kelly E., Firth Z. The Health Foundation; 2020. How is COVID-19 changing the use of emergency care? [Google Scholar]

- 56.$2 Billion to extend critical health services across Australia [press release]. Australian Government, 18/09/2020; 2020. Available from: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/2-billion-extend-critical-health-services-across-australia.

- 57.Mitchell R.D., O’Reilly G.M., Mitra B. Impact of COVID-19 State of Emergency restrictions on presentations to two Victorian emergency departments. Emerg Med Australas. 2020;32(6):1027–1033. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hartnett K.P., Kite-Powell A., DeVies J. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits – United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(23):699–704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Czeisler M.E., Marynak K., Clarke K.E.N. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns – United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250–1257. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsiao J., Sayles E., Antzoulatos E. Effect of COVID-19 on emergent stroke care: a regional experience. Stroke. 2020;51(9):e2111–e2114. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao J., Li H., Kung D. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on stroke care and potential solutions. Stroke. 2020;51(7):1996–2001. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shechter A., Diaz F., Moise N. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;66:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giusti E.M., Pedroli E., D’Aniello G.E. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Belfroid E., van Steenbergen J., Timen A. Preparedness and the importance of meeting the needs of healthcare workers: a qualitative study on Ebola. J Hosp Infect. 2018;98(2):212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Holmgren J., Paillard-Borg S., Saaristo P. Nurses’ experiences of health concerns, teamwork, leadership and knowledge transfer during an Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Nurs Open. 2019;6(3):824–833. doi: 10.1002/nop2.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stuijfzand S., Deforges C., Sandoz V. Psychological impact of an epidemic/pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals: a rapid review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1230. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09322-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miotto K., Sanford J., Brymer M.J. Implementing an emotional support and mental health response plan for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S165–S167. doi: 10.1037/tra0000918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lawn S., Roberts L., Willis E. The effects of emergency medical service work on the psychological, physical, and social well-being of ambulance personnel: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):348. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02752-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gilmartin S., Martin L., Kenny S. Promoting hot debriefing in an emergency department. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2020-000913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nocera M., Merritt C. Pediatric critical event debriefing in emergency medicine training: an opportunity for educational improvement. AEM Educ Train. 2017;1(3):208–214. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.