Abstract

Background: The outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has seriously affected people’s life. The main aim of our investigation was to determine the interactive effects of disease awareness on coping style among Chinese residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: A total of 616 Chinese residents from 28 provinces were recruited to participate in this investigation. A questionnaire was used to collect demographic characteristics, cognition of COVID-19, and disease-related stress sources. Coping styles were assessed via the Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ). Results: The survey showed that the main source of information on COVID-19 was different in relation to gender, age, educational level, and occupation (p < 0.001). People’s knowledge of the disease, preventive measures, and stress factors were different in relation to demographic characteristics (p < 0.001). Compared with the baseline values, the scores of positive coping and negative coping based on SCSQ in relation to gender, age, educational level, and occupation were statistically significant (p < 0.001, except for participants older than 60 years). Different educational levels corresponded to statistical significant differences in positive coping (p = 0.004) but not in negative coping. Conclusions: During the pandemic, people with different characteristics had different levels of preventive measures’ awareness, which influenced their coping styles. Therefore, during public health emergencies, knowledge of prevention and control measures should be efficiently provided to allow more effective coping styles.

Keywords: Coronavirus Disease 2019, cognition, stress source, coping style

1. Introduction

In December 2019, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported and became an outbreak in Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei Province, China [1,2]. The disease is due to infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [3] and it rapidly spread throughout China. On 30 January 2020, the WHO declared the COVID-19 a global public health emergency [4].

During epidemics of infectious diseases, several key preventive measures must be implemented, such as eliminating the source of infection, cutting off the route of transmission, and protecting vulnerable people [5]. Among these measures and at the outbreak stage of COVID-19, however, the infective source could not be easily eliminated. COVID-19 was verified to spread from person to person via aerosols and contact transmissions [6,7]. This information was used to implement protocols which would cut off transmission and would protect vulnerable populations. Even with preventive and therapeutic guidelines for public health emergencies, the general public usually lack medical knowledge and obtain information through various channels, tending to use personal evaluations to adopt the guidelines. Thus, understanding of COVID-19 by the general public plays a significant role during the pandemic.

A public health emergency is a negative stress source, with characteristics of suddenness, infectivity, and extensiveness [8]. Under these circumstances, the understanding of the disease has a relevant role in individuals’ psychological adjustment. General public’s knowledge of COVID-19 for precautionary measures will affect the initial psychological responses and coping styles during the pandemic. Coping is an individual’s cognition and behavioral effort to reduce stress and the emotional response when dealing with an incident that oversteps one’s abilities to manage adversities [9]. The coping style is a mediating variable between stress source and stress response [10,11]. A study [12] reported that individuals with a positive coping strategy usually had a fighting spirit and a better emotional expression performance, which was considered to indicate good psychological adjustment ability, leading to lower anxiety. Coping styles may also influence anxiety through individuals’ normal or pathological changes of biological parameters [13]. A study [14] confirmed that coping resources, especially social support improving mental health, may exert beneficial effects at least in part by reducing the physiological toll of stress. Therefore, people with an appropriate cognitive and coping style would overcome difficulties associated with the COVID-19 pandemic better than those lacking sufficient coping abilities. However, this topic has not been adequately investigated, especially in China, and information on it would be highly useful for the management of future health emergencies. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate how people use their disease knowledge and coping styles to choose preventive measures and control COVID-19.

In our study, Chinese residents were surveyed to determine their main source of information on COVID-19, their knowledge of prevention and control measures for COVID-19, the stress factors mainly affecting them, and their coping styles during the outbreak of COVID-19. The aim of this study was to explore the influence of awareness of COVID-19 on coping styles among Chinese residents and provide a scientific basis for carrying out more accurate prevention and control strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

This cross-sectional study was performed via an online investigation using the snowball sampling techniques. Wenjuanxing (http://www.wjx.cn (accessed on 1 February 2020), Changsha Ranxing Information Technology Co., LTD, Changsha, China) was used to collect the sample. The sample size was calculated according to the formula: N = [Max (dimensions) × 10] × [l + 20%]. Chinese residents from 28 provinces were invited to participate in this investigation from 5 February to 25 February 2020. The study was approved by the human ethics committee of the Mental Health Center of Shantou University.

2.2. Questionnaire

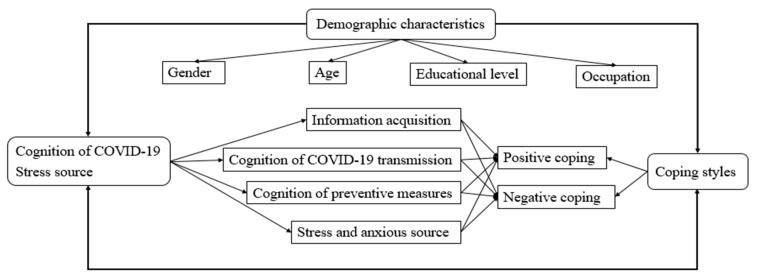

The questionnaire consisted of three parts: (1) General demographic data, including gender, age, educational level, and occupation; (2) Awareness of COVID-19 and stress sources, including the main ways of information acquisition, cognition of COVID-19 transmission routes, cognition of preventive measures, and stress and anxiety factors; (3) Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire, to identify positive and negative coping styles. Path analysis of the hypothesized interactive model was established to evaluate associations between cognition of COVID-19 and coping style (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Path analysis of the hypothesized interactive model.

The Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ) was compiled by Professor Xie [15], based on the cognition theory of coping styles at home and abroad and combined with the characteristics of the Chinese population. The collected data were evaluated for their reliability, and the Cronbach’s α of the SCSQ was 0.90, wherein the Cronbach’s α of the positive coping style was 0.89 and that of the negative coping style was 0.78. The ranking score of each SCSQ item was categorized as follows: not adopted (0), occasionally (1), sometimes (2), usually (3), which would measure the adoption of a more positive coping style in relation to each the domain. The positive coping style subscale consisted of twelve items assessing positive coping characteristics, while the negative coping style subscale involved eight items assessing negative coping characteristics.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistical analysis was used to describe the characteristics of the participants. Categorical variables were represented as percentages, and quantitative variables were denoted as mean ± standard deviation for continuous data. Chi-square tests were used to compare the data for different categorical variables. Significant differences of continuous variables were assessed by the analysis of variance. All tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

A total of 616 participants, 223 males and 393 females, completed the online questionnaire. Most of the participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 59 years (only 3% were 60 years old). More than half of them (71.6%) had an education above the undergraduate level. About 35.9% of the participants had a medical background (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ) scores (mean ± SD) based on demographic characteristics.

| Variables | n | Positive Coping (norm: 1.78 ± 0.52) |

Negative Coping (norm: 1.59 ± 0.66) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 223 | 1.39 ± 0.06 *** | 0.96 ± 0.81 *** |

| Female | 393 | 1.49 ± 0.86 *** | 1.03 ± 0.70 *** |

| p-value | 0.166 | 0.259 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 0–18 | 55 | 1.04 ± 0.81 *** | 0.74 ± 0.72 *** |

| 19–35 | 356 | 1.47 ± 0.88 *** | 1.00 ± 0.72 *** |

| 36–59 | 188 | 1.46 ± 0.88 *** | 1.00 ± 0.73 *** |

| ≥60 | 17 | 1.69 ± 0.49 | 1.55 ± 0.19 |

| p-value | 0.003 | <0.001 | |

| Educational level | |||

| Secondary school or less | 57 | 1.48 ± 0.99 *** | 1.08 ± 0.79 *** |

| Junior college | 118 | 1.19 ± 0.85 *** | 0.87 ± 0.73 *** |

| Undergraduate | 280 | 1.52 ± 0.89 *** | 1.06 ± 0.74 *** |

| Postgraduate or above | 161 | 1.53 ± 0.86 *** | 0.98 ± 0.72 *** |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.091 | |

| Occupation | |||

| With medical background | 221 | 1.42 ± 0.91 *** | 0.86 ± 0.72 *** |

| Without medical background | 395 | 1.47 ± 0.88 *** | 1.09 ± 0.74 *** |

| p-value | 0.517 | <0.001 |

*** Compared with norm, p < 0.001.

3.2. The Association between Cognition of COVID-19 and Demographic Characteristics

Path analysis of the hypothesized interactive model between cognition and coping style was established, as shown in Figure 1. The main way the participants acquired information on COVID-19 was via official news and broadcasts, chat software, timely messages from COVID-19-dedicated APPs, and Internet searching. These data showed significant differences depending on gender, age, educational level, and occupation (p < 0.05) (Table 2). In particular, statistical significance depending on age and educational level (p < 0.05) was reached regarding people’s awareness of COVID-19, aerosol transmission of the disease, contact transmission, fecal or oral transmission, and potential transmission through household items, as shown in Table 3. About the knowledge of preventive measures, such as wearing a mask, avoiding gathering together, washing hands and disinfecting furniture, doing exercise and keeping healthy living habits, the data showed statistical significance depending on gender, age, educational level, and occupation (p < 0.05) (Table 4). In regard to the stress and anxious sources, such as limitations to going outside, impact on one’s original schedule, poor awareness of prevention measures in families, impossibility to reunite with one’s family, uncontrolled information and rumors on the disease, and suspected cases around one’s residence, the data showed statistical significance depending on age, educational level, and occupation (p < 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 2.

Main ways of acquisition of information on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) based on demographic characteristics.

| Variables | Official News and Broadcasts | Short Message Services | Chat Software | Timely Message of APP | Video Clips of APP | Internet Searching | Others | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.039 | |||||||

| Males | 193 (86.6) | 97 (43.5) | 138 (61.9) | 158 (70.9) | 41 (18.4) | 110 (49.3) | 7 (3.1) | |

| Females | 333 (84.7) | 213 (54.2 | 255 (64.9) | 274 (69.7) | 92 (23.4) | 166 (42.2) | 23 (5.9) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||||||

| 0–18 | 41 (74.6) | 37 (67.3) | 37 (67.3) | 34 (61.8) | 27 (49.1) | 23 (41.8) | 4 (7.3) | |

| 19–35 | 311 (87.4) | 181 (50.8) | 210 (59.0) | 272 (76.4) | 76 (21.4) | 155 (43.5) | 17 (4.8) | |

| 36–59 | 157 (83.5) | 88 (83.5) | 130 (83.5) | 116 (83.5) | 30 (83.5) | 93 (83.5) | 9 (83.5) | |

| ≥60 | 17 (100.0) | 4 (23.5) | 16 (58.8) | 10 (58.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (29.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Educational level | <0.001 | |||||||

| Secondary school or less | 48 (84.2) | 23 (40.4) | 36 (63.2) | 28 (49.1) | 10 (17.5) | 22 (38.6) | 4 (7.0) | |

| Junior college | 98 (83.1) | 75 (63.6) | 76 (64.4) | 70 (59.3) | 46 (39.0) | 43 (36.4) | 7 (5.9) | |

| Undergraduate | 248 (88.6) | 141 (50.4) | 177 (63.2) | 207 (73.9) | 52 (18.6) | 131 (46.8) | 16 (5.7) | |

| Postgraduate or above | 132 (82.0) | 71 (44.1) | 104 (64.6) | 127 (79.0) | 25 (15.5) | 80 (49.7) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Occupation | 0.002 | |||||||

| With medical background | 198 (89.6) | 111 (50.2) | 123 (55.7) | 155 (70.1) | 35 (15.8) | 102 (46.2) | 8 (3.6) | |

| Without medical background | 328 (83.0) | 199 (50.4) | 270 (68.4) | 277 (70.1) | 98 (24.8) | 174 (46.2) | 22 (5.6) |

Table 3.

Cognition of COVID-19 transmission based on demographic characteristics.

| Variables | Droplet Transmission | Contact Transmission | Fecal/Oral Transmission | Household Articles Transmission | Others | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.165 | |||||

| Males | 223 (100.0) | 196 (87.9) | 182 (81.6) | 156 (70.0) | 15 (6.7) | |

| Females | 390 (99.2) | 355 (90.3) | 290 (73.8) | 266 (67.7) | 28 (7.1) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 0–18 | 54 (98.2) | 48 (87.3) | 36 (65.5) | 35 (63.6) | 1 (1.8) | |

| 19–35 | 355 (99.7) | 310 (87.1) | 288 (80.9) | 238 (66.9) | 20 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| 36–59 | 187 (99.5) | 176 (93.6) | 132 (70.2) | 138 (73.4) | 21 (11.2) | |

| ≥60 | 17 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 16 (94.1) | 11 (64.7) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Secondary school or less | 54 (94.7) | 47 (82.5) | 44 (77.2) | 37 (64.9) | 5 (8.8) | |

| Junior college | 118 (100.0) | 104 (88.1) | 87 (73.7) | 82 (69.5) | 6 (5.1) | <0.001 |

| Undergraduate | 280 (100.0) | 246 (87.9) | 215 (76.8) | 196 (70.0) | 21 (7.5) | |

| Postgraduate or above | 161 (100.0) | 154 (95.7) | 126 (78.3) | 107 (66.5) | 11 (6.8) | |

| Occupation | 0.07 | |||||

| With medical background | 221 (100.0) | 200 (90.5) | 171 (77.4) | 138 (62.4) | 11 (4.98) | |

| Without medical background | 392 (99.2) | 351 (88.9) | 301 (76.2) | 284 (71.9) | 32 (8.1) |

Table 4.

Cognition of preventive measures based on demographic characteristics.

| Variables | Wear a Mask | Avoid Gathering Together | Wash Hands and Disinfect Furniture | Exercise | Raise the Room Temperature | Healthy Living Habits | Vinegar Vapors | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.003 | |||||||

| Males | 223 (100.0) | 217 (97.3) | 213 (95.5) | 195 (87.4) | 35 (15.7) | 204 (91.5) | 18 (8.1) | |

| Females | 390 (99.2) | 390 (99.2) | 392 (99.8) | 341 (86.8) | 68 (17.3) | 349 (88.8) | 35 (8.9) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 0–18 | 55 (100.0) | 55 (100.0) | 55 (100.0) | 42 (76.3) | 15 (27.3) | 40 (72.7) | 10 (18.2) | |

| 19–35 | 353 (99.2) | 349 (98.0) | 352 (98.9) | 306 (86.0) | 65 (18.3) | 326 (91.6) | 29 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| 36–59 | 188 (100.0) | 186 (98.9) | 182 (96.8) | 171 (91.0) | 22 (11.7) | 171 (91.0) | 14 (7.5) | |

| ≥60 | 17 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 16 (94.1) | 17 (100.0) | 1 (5.9) | 16 (94.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Secondary school or less | 57 (100.0) | 55 (96.5) | 54 (94.7) | 43 (75.4) | 10 (17.5) | 46 (80.7) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Junior college | 118 (100.0) | 115 (97.5) | 115 (97.5) | 95 (80.5) | 21 (17.8) | 97 (82.2) | 17 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Undergraduate | 278 (99.3) | 278 (99.3) | 279 (99.6) | 251 (89.6) | 54 (19.3) | 259 (92.5) | 26 (9.3) | |

| Postgraduate or above | 160 (99.4) | 159 (98.8) | 157 (97.5) | 147 (91.3) | 18 (11.2) | 151 (93.8) | 9 (5.6) | |

| Occupation | 0.050 | |||||||

| With medical background | 218 (98.6) | 216 (97.7) | 217 (98.2) | 189 (85.5) | 33 (14.9) | 204 (92.3) | 13 (5.9) | |

| Without medical background | 395 (100.0) | 391 (99.0) | 388 (98.2) | 347 (87.9) | 70 (17.7) | 349 (88.4) | 40 (10.1) |

Table 5.

Stress and anxious sources based on demographic characteristics.

| Variables | Limited Going Outside | Going to Work Early | Impact on the Original Schedule | Poor Preventive Measures’ Awareness of Families | Unable to Reunite with Families | Uncontrolled Information and Rumors | Suspected Cases around One’s Residence | Others | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.493 | ||||||||

| Males | 151 (67.7) | 33 (14.8) | 120 (53.8) | 47 (21.1) | 45 (20.2) | 109 (48.9) | 54 (24.2) | 14 (6.3) | |

| Females | 265 (67.4) | 68 (17.3) | 175 (44.5) | 88 (22.4) | 78 (19.9) | 195 (49.6) | 78 (19.9) | 23 (5.9) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 0–18 | 44 (80.0) | 2 (3.6) | 20 (36.4) | 6 (10.9) | 5 (9.1) | 14 (25.5) | 5 (9.1) | 3 (5.5) | |

| 19–35 | 240 (67.4) | 65 (18.3) | 170 (47.8) | 109 (30.6) | 71 (19.9) | 195 (54.8) | 88 (24.7) | 19 (5.3) | |

| 36–59 | 115 (61.2) | 34 (18.1) | 92 (48.9) | 18 (9.6) | 46 (24.5) | 86 (45.7) | 38 (20.2) | 15 (8.0) | |

| ≥60 | 17 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (76.5) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (5.9) | 9 (52.9) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Educational level | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Secondary school or less | 43 (75.4) | 4 (7.0) | 26 (45.6) | 6 (10.5) | 4 (7.0) | 17 (29.8) | 5 (8.8) | 3 (5.3) | |

| Junior college | 86 (72.9) | 8 (6.8) | 40 (33.9) | 18 (15.3) | 21 (17.8) | 48 (40.7) | 19 (16.1) | 8 (6.8) | |

| Undergraduate | 186 (66.4) | 53 (18.9) | 134 (47.9) | 79 (28.2) | 59 (21.7) | 153 (54.6) | 73 (26.1) | 19 (6.8) | |

| Postgraduate or above | 101 (62.7) | 36 (22.4) | 95 (59.0) | 32 (19.9) | 39 (24.2) | 86 (53.4) | 35 (21.7) | 7 (4.4) | |

| Occupation | <0.001 | ||||||||

| With medical background | 127 (57.5) | 49 (22.2) | 106 (48.0) | 59 (26.7) | 51 (23.1) | 122 (55.2) | 55 (24.9) | 10 (4.5) | |

| Without medical background | 289 (73.2) | 52 (13.2) | 189 (47.9) | 76 (19.2) | 72 (18.2) | 182 (46.1) | 77 (19.5) | 27 (6.8) |

3.3. Association between SCSQ and Demographic Characteristics

Univariate analysis of variance was used to analyze gender, age, educational level, and occupation among the participants. Compared with the baseline values, positive and negative coping depending on gender, age, educational level and occupation were statistically significant (p < 0.001, except for age ≥ 60 years). When comparing the coping style scores of males and females, we did not find statistical significant differences (p > 0.05). Different age groups showed statistically significant differences in both positive coping (p < 0.05) and negative coping (p < 0.001). People with different educational levels showed statistically significant differences regarding positive coping (p < 0.05) but not negative coping (p > 0.05). Undergraduates, postgraduates, or above were more likely to get higher scores. When comparing people with or without a medical background, statistically significant differences were not found in positive coping (p > 0.05); however, they were found in negative coping (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

4. Discussion

Our study was conducted to determine how people use their knowledge of the disease and coping styles to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic in China. The results showed that people received information about COVID-19 by multiple media, such as official news and broadcasts, chat software, timely messages from dedicated APPs, and Internet searching. Totally, the Internet was the primary information channel for the Chinese during the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Internet access was so diversified in terms of visited websites that it might have been difficult to distinguish between real news and rumors [16,17]. Searching information on the Internet has become rife, and even more common during the COVID-19 outbreak. Much of the online information, especially rumors, may cause anxieties and worries [18,19]. Therefore, it is necessary to make full use of official media, refute rumors, and invest more in health education and public health services [20,21].

Most of the surveyed people thought that COVID-19 transmission was via aerosols, direct contact, and fecal/oral routes [22]; they also showed cognition of preventive measures including wearing a mask, avoiding gathering, keeping healthy habits, and so on. These results showed that the surveyed people generally understood the danger and the risks posed by COVID-19 and demonstrated a strong sense of self-protection. During the pandemic, education authorities and enterprises need to develop web-based applications to deliver teaching activities or work tasks [23]. Health authorities could consider providing online or smartphone-based health education, such as on COVID-19 transmission and preventive measures, to reduce risk of virus transmission in face-to-face meetings [24,25]. Government and health authorities need to provide accurate health information during the pandemic to reduce the impact of rumors [26].

The outbreak of COVID-19 is wreaking havoc worldwide, and the pandemic has entered a dangerous new phase [27]. This immediate spread of the pandemic causes anxiety and stress [28]. Various studies [29,30] showed that stress can cause a variety of somatic symptoms as well as mental illness. Psychological stress appears when individuals perceive the impact of the external environment on their emotions and social functions [31]. It can cause adaptive or adverse reactions, are influenced by individual personality characteristics and coping styles [32]. A study [33] reported that ways of coping in stressful conditions do not operate on adjustment in isolation, but on psychosocial parameters in relation to adaptive outcomes. The psychosocial parameters include the characteristics of the stressor, the social context, dispositional attributes, and cognitive appraisals. A public health emergency (COVID-19) is one of the influencing factors of psychosocial parameters. Coping mainly involve changing the evaluation and cognition of the stressful event and adjusting the physical and emotional responses, thus controlling the influence of stressful event [34].

In this study, the effects of information acquisition and cognition of preventive measures for COVID-19 on coping were of statistical significance in different age groups, and the scores of coping styles in different age groups were lower than the baseline scores, which indicates that the public health emergency affected people’s awareness of the disease and coping styles. The positive coping scores of people aged 60 years were higher than those of other age groups, which might be related to the rich social experience and stable psychological qualities of older people [35]. People aged between 19 and 35 years and between 36 and 59 years got similar scores, but still lower than the baseline ones. These age groups included college students and workers in various industries, which indicates the widespread impact of the pandemic on people, especially on those representing the main working force of the society [36]. It is well known that different age groups in different life phases would show variations in response to different types of stressors [37]. For example, young adults would most likely encounter school-related stressors, middle-aged adults work-related stressors, and older adults health-related stressors [38,39]. Our data show that during the pandemic of COVID-19, people of all age groups perceived fear and felt their health threatened and that they adopted different coping styles.

The effects of information acquisition and cognition of preventive measures for COVID-19 on coping were statistically significant, depending on educational levels and the corresponding coping style scores were lower than the baseline ones, with the adoption of a positive coping style having statistical significance. People with undergraduate and postgraduate or above education obtained higher scores than other groups in relation to positive coping, which indicates that people with high educational levels had better knowledge of COVID-19 and Please check if the original meaning is retained. Indeed, their acquired habit of reasoning and logical managing ability would allow them to better cope with emergencies than people with lower educational levels [40]. In addition, our data are consistent with the assumption that a high educational level is a predictive factor for the incidence of non-communicable diseases, with limited mediating effects from socioeconomic status and healthy behavior [41]. A high educational level was reported to improve COVID-19 knowledge among Chinese and to be associated with having a positive attitude and adopting appropriate practices [42]. Intraindividual factors, including coping resources and cognitive appraisals, also affect coping processes. In addition to their role as mediators, coping processes also can interact with contextual and individual parameters in their contribution to adjustment. Newer models for conceptualizing the links among stressful life experiences, coping processes, and mental health outcomes also recognize their potentially reciprocal relations [33], which is consistent with the path analysis of the hypothesized interactive model of our study.

During the pandemic of COVID-19, the scores for positive and negative coping styles of people without a medical background were higher than those of medical workers, which may be link to poor preventive measures’ awareness and lack of professional knowledge to interpret scientific information. At the same time, medical workers were under relatively high stress in a high-risk environment, and the positive coping score of the people without a medical background was higher than that of medical workers, though the difference was not statistically significant. People with a medical background obtained lower scores in negative coping, which is consistent with their professional knowledge and occupational training [43]. Their expertise certainly allowed them to acquire a higher degree of comfort and control over the situations created by the pandemic. In addition, this group would continuously receive updated guidelines [44] and a rapid supply of medical protective items, which allowed them to maintain a positive coping attitude during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the government and institutions should provide targeted mental and cognitive guidance and carry out behavioral interventions, especially for medical workers during the pandemic, to properly release the pressure they experience.

Limitations and strengths of this study. The present study has several limitations. First, earlier life/stress events and cognition activities were not considered in our study. Second, this study only reflected people’s awareness of COVID-19 and coping style in a phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, though a longitudinal approach might help perform a dynamic observation of these phenomena. Third, detailed random sampling and on-site investigation were difficult to carry out during the pandemic of COVID-19. Despite these limitations, interactive effects were established to evaluate the association between COVID-19 awareness and coping styles of Chinese residents in the early time of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the future, it may be interesting to design a study to investigate the effect of early life events on individuals’ COVID-19 awareness and coping style. A study with dynamic observation of disease cognition and considering behavioral coping interventions should be performed to collect more epidemiological data.

5. Conclusions

During the pandemic, people with different individual characteristics showed different levels of COVID-19 preventive measures’ awareness, which influenced their coping styles. Most people adopted a positive coping style, but the coping scores were still below the baseline scores. During public health emergencies, the knowledge of preventive and control measures should be strengthened so to scientifically guide the population to adopting a correct coping style.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.W. and Z.C.; methodology, K.W. and Z.C.; software, Z.C.; formal analysis, Z.C.; investigation, Z.C., S.Z., Y.H. and Z.Q.; resources, K.W. and Y.H.; data curation, Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.C.; writing—review and editing, K.W., W.W.A. and Z.C.; visualization, Z.C. and S.Z.; project administration, Z.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by 2020 Li Ka Shing Foundation Cross-Disciplinary Research Grant, grant number 2020LKSFG04A and the special fund for science and technology of Guangdong Province.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the human ethics committee of the Mental Health Center of Shantou University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Du Z., Wang L., Cauchemez S., Xu X., Wang X., Cowling B.J., Meyers L.A. Risk for transportation of coronavirus disease from Wuhan to other cities in China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1049–1052. doi: 10.3201/eid2605.200146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu N., Li W., Kang Q., Xiong Z., Wang S., Lin X., Liu Y., Xiao J., Liu H., Deng D., et al. Clinical features and obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective, single-centre, descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:559–564. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30176-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Coronavirus. [(accessed on 1 February 2020)];2020 Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus/coronavirus.

- 4.WHO Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding The Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [(accessed on 2 February 2020)];2020 Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)

- 5.Thompson R.N., Brooks-Pollock E. Preface to theme issue “Modelling infectious disease outbreaks in humans, animals and plants: Epidemic forecasting and control”. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2019;374:20190375. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2019.0375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan J.F.-W., Yuan S., Kok K.-H., To K.K.-W., Chu H., Yang J., Xing F., Liu J., Yip C.C.-Y., Poon R.W.-W. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: A study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., Ren R., Leung K.S.M., Lau E.H.Y., Wong J.Y., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel Coronavirus-infected Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Y., Liu N. Methodology of emergency medical logistics for public health emergencies. Transp. Res. E. Logist. Transp. Rev. 2015;79:178–200. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geuens N., Verheyen H., Vlerick P., Bogaert P.V., Franck E. Exploring the influence of core-self evaluations, situational factors, and coping on nurse burnout: A cross-sectional survey study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0230883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryu G.W., Yang Y.S., Choi M. Mediating role of coping style on the relationship between job stress and subjective well-being among Korean police officers. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:470. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08546-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao X., Wang J., Shi C. The influence of mental resilience on the positive coping style of air force soldiers: A moderation- mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:550. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Classen C., Koopman C., Angell K., Spiegel D. Coping styles associated with psychological adjustment to advanced breast cancer. Health Psychol. 1996;15:434–437. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.15.6.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papava I., Oancea C., Enatescu V.R., Bredicean A.C., Dehelean L., Romosan R.S., Timar B. The impact of coping on the somatic and mental status of patients with COPD: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2016;11:1343–1351. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S106765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor S.E., Lehman B.J., Kiefe C.I., Seeman T.E. Relationship of early life stress and psychological functioning to adult C-reactive protein in the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;60:819–824. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie Y. A preliminary study on reliability and validity of simple cope style questionnaire. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 1998;6:114–115. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kouzy R., Jaoude J.A., Kraitem A., El Alam M.B., Karam B., Adib E., Zarka J., Trabousli C., Akl E.W., Baddour K. Coronavirus goes viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 misinformation epidemic on Twitter. Cureus. 2020;12:e7255. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y., McKee M., Torbica A., Stuckler D. systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;240:112552. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ni M.Y., Yang L., Leung C.M.C., Li N., Yao X.I., Wang Y., Leung G.M., Cowling B.J., Liao Q. Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and cordon sanitaire among the community and health professionals in Wuhan, China: Cross-sectional survey. JMIR Ment. Health. 2020;7:e19009. doi: 10.2196/19009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jo W., Lee J., Park J., Kim Y. Online information exchange and anxiety spread in the early stage of the novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak in South Korea: Structural topic model and network analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e19455. doi: 10.2196/19455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J., Xu Q., Cuomo R., Purushothaman V., Mackey T. Data mining and content analysis of the chinese social media platform Weibo during the early COVID-19 outbreak: Retrospective observational infoveillance study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e18700. doi: 10.2196/18700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han X., Wang J., Zhang M., Wang X. Using social media to mine and analyze public opinion related to COVID-19 in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:2788. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo Y.R., Cao Q.-D., Hong Z.-S., Tan Y.-Y., Chen S.-D., Jin H.-J., Tan K.-S., Wang D.-Y., Yan Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak—An update on the status. Mil. Med. Res. 2020;7:11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vokinger K.N., Nittas V., Witt C.M., Fabrikant S.I., von Wyl V. Digital health and the COVID-19 epidemic: An assessment framework for apps from an epidemiological and legal perspective. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2020;150:w20282. doi: 10.4414/smw.2020.20282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prem K., Liu Y., Russel T.W., Kucharski A.J., Eggo R.M., Davies N., Jit M., Klepac P. Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: A modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e261–e270. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30073-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colbourn T. COVID-19: Extending or relaxing distancing control measures. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e236–e237. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin G.J., Wessely S. The psychological effects of quarantining a city. BMJ. 2020;368:m313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vellingiri B., Jayaramayya K., Iyer M., Narayanasamy A., Govindasamy V., Giridharan B., Ganesan S., Venugopal A., Venkatesan D., Ganesan H. COVID-19: A promising cure for the global panic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;725:138277. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Razai M.S., Oakeshott P., Kankam H., Galea S., Stokes-Lampard H. Mitigating the psychological effects of social isolation during the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;369:m1904. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herr R.M., Li J., Loerbroks A., Angerer P., Siegrist J., Fischer J.E. Effects and mediators of psychosocial work characteristics on somatic symptoms six years later: Prospective findings from the Mannheim Industrial Cohort Studies (MICS) J. Psychosom. Res. 2017;98:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slavich G.M., Irwin M.R. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: A social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol. Bull. 2014;140:774–815. doi: 10.1037/a0035302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pisanski K., Kobylarek A., Jakubowska L., Nowak J., Walter A., Błaszczyński K., Kasprzyk M., Łysenko K., Sukiennik I., Piątek K., et al. Multimodal stress detection: Testing for covariation in vocal, hormonal and physiological responses to Trier Social Stress Test. Horm. Behav. 2018;106:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwiatosz-Muc M., Fijałkowska-Nestorowicz A., Fijałkowska M., Aftyka A., Pietras P., Kowalczyk M. Stress coping styles among anaesthesiology and intensive care unit personnel - links to the work environment and personal characteristics: A multicentre survey study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019;33:661–668. doi: 10.1111/scs.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor S.E., Stanton A.L. Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007;3:377–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takamoto M., Aikawa A. The effect of coping and appraisal for coping on mental health and later coping. Shinrigaku Kenkyu. 2013;83:566–575. doi: 10.4992/jjpsy.83.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neupert S.D., Bellingtier J.A. Daily stressor forecasts and anticipatory coping: Age differences in dynamic, domain-specific processes. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2019;74:17–28. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y., Peng Y., Xu H., O’Brien W. Age differences in stress and coping: Problem-focused strategies mediate the relationship between age and positive affect. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2018;86:347–363. doi: 10.1177/0091415017720890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young N.A., Mikels J.A. Paths to positivity: The relationship of age differences in appraisals of control to emotional experience. Cogn. Emot. 2020;34:1010–1019. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2019.1697647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stawski R.S., Scott S.B., Zawadzki M.J., Sliwinski M.J., Marcusson-Clavertz D., Kim J., Lanza S.T., Green P.A., Almeida D.M., Smyth J.M. Age differences in everyday stressor-related negative affect: A coordinated analysis. Psychol. Aging. 2019;34:91–105. doi: 10.1037/pag0000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bellingtier J.A., Neupert S.D., Kotter-Grühn D. The combined effects of daily stressors and major life events on daily subjective ages. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017;72:613–621. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silagi M.L., Romero V.U., Mansur L.L., Radanovic M. Inference comprehension during reading: Influence of age and education in normal adults. Codas. 2014;26:407–414. doi: 10.1590/2317-1782/20142013058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oshio T., Kan M. Educational level as a predictor of the incidences of non-communicable diseases among middle-aged Japanese: A hazards-model analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:852. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7182-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhong B.L., Luo W., Zhang Q.-Q., Liu X.-G., Li W.-T., Li Y. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: A quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16:1745–1752. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chowell G., Abdirizak F., Lee S., Lee J., Jung E., Nishiura H., Viboud C. Transmission characteristics of MERS and SARS in the healthcare setting: A comparative study. BMC Med. 2015;13:210. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0450-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chinanews Two Departments Issue The Novel Coronavirus Infection Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Plan. (Trial Version 7) [(accessed on 3 February 2020)];2020 Available online: http://www.chinanews.com/gn/2020/03-04/9113100.shtml.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.