Abstract

There is an increasing number of new therapies for severe asthma; however, what outcomes people with severe asthma would like improved and what aspects they prioritise in new medications remain unknown. This study aimed to understand what outcomes are important to patients when prescribed new treatments and to determine the characteristics of importance to patients in their choice of asthma treatments.

Participants with severe asthma (n=50) completed a cross-sectional survey that ranked 17 potential hypothetical outcomes of treatment using a seven-point Likert scale, as well as selecting their top five overall outcomes. Participants also completed hypothetical scenarios trading off medication characteristics for four hypothetical add-on asthma treatments.

Participants (58% male), had a mean±sd age of 62.2±13.5 years. Their top three prioritised outcomes were: to improve overall quality of life (selected by 83% of people), reduce number and severity of asthma attacks (72.3%), and being able to participate in physical activity (59.6%) When trading off medication characteristics, the majority of patients with severe asthma chose the hypothetical medication with the best treatment efficacy (68%). However, a subgroup of patients prioritised the medication's side-effect profile and mode of delivery to select their preferred medication.

People with severe asthma value improved quality of life as an important outcome of treatment. Shared decision-making discussions between clinicians and patients that centre around medication efficacy and side-effect profile can incorporate patient preferences for add-on therapy in severe asthma.

Short abstract

Improving quality of life is an important treatment outcome. Shared decision-making discussions between clinicians and patients that centre around efficacy and side-effect profile incorporate patient preferences for add-on therapy in severe asthma. https://bit.ly/2GY1Sc4

Introduction

Severe asthma is a complex chronic disease with a burdensome symptom profile and is associated with frequent asthma attacks, increased healthcare use, significant comorbidity and an increased mortality risk [1–4]. Recent advances have resulted in an increasing number of efficacious add-on treatment options for people with severe asthma [5–11]. Accordingly, patients and health professionals now have increased options for treatments, which also requires them to choose between different therapeutic options. Whilst these treatment decisions should be guided by the healthcare professional in terms of appropriate asthma phenotyping and predictors of response, there may be times where one individual might respond to a number of different treatments; therefore, understanding the patient's perspective may lead to rational prescribing that considers the holistic needs of patients.

The treatments currently available for asthma differ in the outcomes they target, which is likely to be an important factor in drug choice. Clinical trials have focussed on outcomes that have been recommended by regulatory bodies, such as lung function, oral corticosteroid (OCS) use, asthma control and asthma exacerbations [7–9]. Whilst these outcomes have been identified as important from a clinician's perspective [12], the outcomes of most importance to patients with severe asthma remain unknown. Prior research examining symptom control in asthma identified cough and breathlessness as key symptoms that people with asthma wish to prioritise [13]; however, other outcomes that may be important to people with severe asthma remain unexplored.

Understanding what aspects of treatment patients consider a priority is important in guiding shared decision-making between patient and clinician discussions [14, 15]. Gelhorn et al. [16] evaluated treatment preferences for monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapies in severe asthma and illustrated that clinicians and patient preferences align in regard to favouring less frequent dosing and faster time to treatment efficacy. However, preferences in terms of the impact of side-effect profiles or treatment efficacy have not been examined, nor has the relative priority of different medication attributes. Therefore, we aimed to understand what outcomes patients would like their add-on asthma treatments to improve and to determine whether patients have an overall preference for different medication attributes when asthma treatment efficacy, side-effect profile and mode of administration each are hypothetically traded off against each other. We hypothesised that patients would prioritise quality of life as their most important outcome and prefer the medication that provided the greatest efficacy.

Materials and methods

Study design

After obtaining ethical approval (Hunter New England Human Research Ethics: 16/05/8/5.02) and written informed consent, participants with severe asthma were recruited to a cross-sectional survey.

Setting

Recruitment occurred from the research database and clinics of the Department of Sleep and Respiratory Medicine (May 2018 to March 2019) at a tertiary referral hospital in Australia.

Inclusion

Adult (≥18 years) participants (n=50) with a prior confirmed doctor diagnosis of severe persistent asthma were recruited. Severe asthma was defined based on the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society taskforce [17] as being on high-dose treatment with inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting β2-agonist or required mAb therapy for severe asthma.

Assessments

Demographic characteristics, self-reported disease-related characteristics and a paper-based survey (see supplementary material) about medication and outcome preferences were collected during a face-to-face assessment with a researcher (VLC).

Questionnaire

Survey design

The design of the survey was informed by the study aims and a review of the severe asthma patient experience literature [18–20]. As no suitable instrument existed, the survey was developed by the research team (P.G. Gibson and V.M. McDonald, expert severe asthma multidisciplinary clinicians, and V.L. Clark, a behavioural scientist). The survey had two components: The first assessed “outcomes of importance” using 17 statements related to outcomes that people with severe asthma would like treated as part of their severe asthma management (figure 1). The statements were derived from the literature regarding living with severe asthma [18–20]. The second component was based on “treatment aspect preferences”, which included the presentation of hypothetical scenarios in which the participant was asked to consider multiple attributes within the scenario and decide which medication best met their needs. The scenarios were designed based on the best–worst scaling survey method [21] considering the Likelihood of Action component of the Health Belief Model [22, 23]. This model is based on understanding the balance of the perceived benefit of preventative action (benefit to asthma symptoms) weighted against the perceived barriers (potential side-effects, burden of receiving the treatment). The scenarios addressed the aspects of a medication that been identified in the literature as important in decision-making in regard to treatment [24–26].

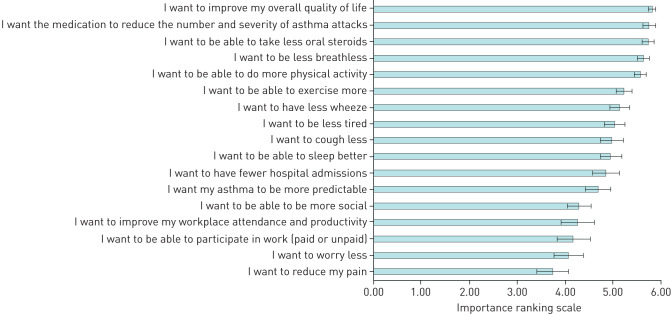

FIGURE 1.

Outcomes of importance for people with severe asthma. Ranking on a 0 (this is not important to me) to 6 (this is very important to me) point Likert scale. Data are presented as mean±sd.

Component 1: outcomes of importance to patients

Individual outcomes of importance

Participants ranked 17 statements (figure 1) related to severe asthma outcomes (examples include, reductions in acute attacks or OCS use) on a seven-point Likert scale (0: “not important to me” to 6: “very important to me”).

Overall outcomes of importance

After participants rated the 17 outcomes, they nominated the five outcomes that were most important to them, with one being the most important. Participants were also asked a free text question asking if there were any additional outcomes they would like addressed.

Component 2: treatment aspect preferences

Considerations for making a medication choice

Participants answered an open-ended question: “are there any other factors which you think are important to consider when choosing between two or more medications?”

Ranking the aspects of treatment

Participants ranked in order of one to four (one being the most important) what treatment aspects they thought were the most important to them in terms of their asthma management (e.g. asthma treatment efficacy, logistics (how your medication is administered), side-effects or the personal cost of your medication).

Hypothetical scenarios

Participants ranked four different medications in order of most preferred to least preferred in four separate scenarios. In the first scenario “asthma treatment efficacy” participants were presented with a series of statements related to their asthma management (table 1), e.g., “if I have this treatment I am likely to have fewer bad attacks”. Each statement was given an expected impact for each medication, e.g. for Medication A “On average, my bad asthma attacks would reduce by just over one-third”; for Medication B “On average, my bad asthma attacks would reduce by about half”. The four hypothetical medications were modelled on treatment effects observed in the large-scale randomised controlled trials for severe asthma add-on therapies currently available in Australia (omalizumab, mepolizumab, benralizumab and azithromycin). The medications were displayed to the participants as medication A, B, C and D. They included three injectable medications (omalizumab=A, mepolizumab=B, benralizumab=C), and one oral tablet (azithromycin=D). Participants were asked to consider all the statements and medication properties within each scenario and select the medication that best met their preferences, that is, their most preferred treatment choice. After each scenario, participants were also asked a free text question: “Why did you choose this medication?”

TABLE 1.

Example of the first hypothetical scenario

| Asthma outcomes | Medication A | Medication B | Medication C | Medication D |

| I am likely to have fewer bad attacks | On average, my bad asthma attacks would reduce by just over one-third | On average, my bad asthma attacks would reduce by about half | On average, my bad asthma attacks would reduce by more than half | On average, my bad asthma attacks would reduce by just under half |

| I am likely to have an improvement in the control of my asthma (for example, have less symptoms) | ☺ | ☺ | ☺ | ☺ |

| I am likely to achieve an improvement in how my asthma symptoms affect my daily life (such as having to avoid social situations, completing my daily tasks of living) | ☺☺ | ☺☺ | ☺☺☺ | ☺ |

| I am likely to reduce my oral steroids (prednisone) | On average my steroid dose would reduce by just under half | On average my steroid dose would reduce by half | On average my steroid dose would reduce by up to three-quarters | Steroid reduction not known |

| Thinking about the above information, which medication would you choose? (Rank 1 (this is the one I want!) to 4 (this is the one I would prefer least)) | ||||

| What was the main reason you chose that medication? | ||||

Participants were provided with the following instructions. “There are different medicines that may work for you to help treat your severe asthma. We would like to understand what is most important to you in terms of your asthma medicines. To help us understand this, I'm going to present you with a series of scenarios in which you can choose one of four different medications. There are no right or wrong answers here, we just want to get an understanding of what you want from your severe asthma medicine”. “We have provided some information about each of these treatments. We would like you to consider each of the medications and tell us which medication most meets your preferences”. ☺: Improves a little; ☺☺: improves a fair bit; ☺☺☺: improves a lot.

This process was repeated for the second scenario “logistics” (how the medication is received, how frequently) and third scenario “side-effects profile”. In the fourth scenario these three aspects of treatment (“asthma treatment efficacy”, “logistics” and “side-effects”) were combined and participants were asked to consider all aspects of treatment collectively. This enabled the participant to weigh the benefits of the four hypothetical medications compared to each other, trading off the benefits of treatment against the perceived barriers.

Analysis

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS statistics v25. Free text responses were analysed using content analysis. Subgroups were compared using analysis of variance, and significance levels were set at p<0.05. Dichotomous subgroups compared age (≥65 and above versus ≤64), sex (male versus female), asthma control (controlled, Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) <1.5 versus poor control, ACQ ≥1.5), asthma attack prone (>2 asthma attacks in the past year versus ≤2 asthma attacks in the past year), prescription of mAb therapy (prescribed versus not prescribed), duration of mAb therapy (≥6 months versus <6 months) and maintenance prednisone prescription (prescribed versus not prescribed). Preference data were reported using proportions. There was sufficient power to detect group differences of a large effect size (d=0.8), at 80% power, for a two-tailed significance test with p<0.05.

Results

Demographic details are displayed in table 2. Participants were predominately male and had poorly controlled asthma; 92% (n=46) of respondents reported at least one asthma attack in the past year, 38% of the sample were prescribed maintenance (daily) OCS and 88% of participants had been prescribed at least one course of oral OCS for >3 days within the past year (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Patient demographics

| Subjects | 50 |

| Age years | 62.20±13.47 |

| Male | 30 (57.69) |

| Living arrangement | |

| Living alone | 9 (20.93) |

| Living with spouse/family | 34 (79.07) |

| Employment status | |

| Retired | 26 (57.78) |

| Not working for medical reasons | 7 (15.56) |

| Working (full- or part-time) | 12 (26.67) |

| Age of asthma diagnosis years | 23.60±21.45 |

| ACQ score | 2.01±1.27 |

| Exacerbations in past year | 3.00 (2–5) |

| Maintenance OCS prescription | 19 (38) |

| OCS daily dose mg | 7.00 (5.00–25.00) |

| ICS daily dose beclomethasone equivalent units | 2000 (1000–2000) |

| Add-on severe asthma medication | 41 (82) |

| Azithromycin | 11¶ (22) |

| Mepolizumab | 27 (54) |

| Omalizumab | 10 (20) |

| Benralizumab | 3 (6) |

| Teplizumab# | 1 (2) |

| No add-on therapy | 9 (18) |

| Months of monoclonal antibody therapy | 7 (3–24) |

Data are presented as n, n (%), mean±sd or median (interquartile range). ACQ: asthma control questionnaire; IQR: interquartile range; OCS: oral corticosteroid; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid. #: one participant was on a clinical trial of teplizumab in the survey group; ¶: azithromycin was an add-on therapy to the monoclonal medications in all but one participant.

Component 1: Outcomes of importance to patients

Individual outcomes of importance

The outcome “I want to improve my overall quality of life” was the highest rated (figure 1), with most participants (86%, n=43) scoring this at the highest possible score, followed by “…reduce the number and severity of attacks”, and “…take less oral steroids”. The outcomes “I want to be less breathlessness” and “…be able to do more physical activity” (figure 1) were also rated highly.

Overall outcomes of importance

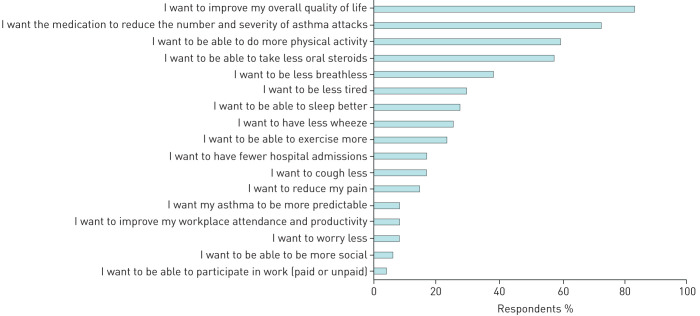

Figure 2 shows the proportion of people who nominated each outcome anywhere in their top five responses. Improving overall quality of life was the most frequently selected outcome, with 83% of participants choosing it in their top five. Reducing the number and severity of attacks was also an important priority among patients' top five responses (72.3%) (figure 2). Being able to participate in physical activity was considered the third most important outcome (figure 2), followed by a reduction in OCS. Reducing OCS was a concern for patients who were taking them on a daily basis, but this group only made up 44.4% of participants who selected this outcome as a priority; the remainder 56.4% of people were only taking OCS as needed. In the free text responses, 32% of participants reiterated that they would like an improvement in quality of life, 16% reiterated that they wanted a reduction in OCS. Additionally, 14% of people wanted to be able to participate in physical activity, and 12% mentioned they wanted stable asthma and less wheeze.

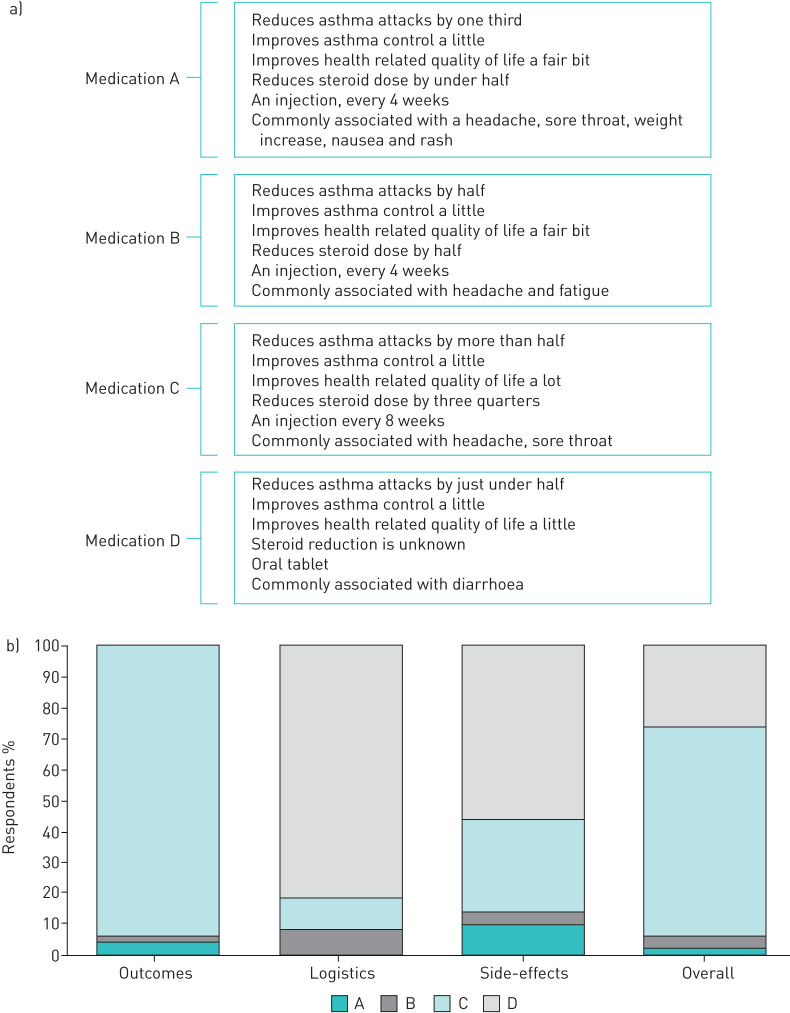

FIGURE 4.

a) Overview of the features of the hypothetical medications. Several of the side-effects were “not a known side-effect”. b) Proportion of preference for each medication based on the effect of the medication on asthma treatment efficacy “outcomes” (exacerbations, steroid reduction), the logistics of the medication (tablet, injection, frequency of dose), potential side-effects of the medication and all these factors overall.

Subgroup comparison of individual outcomes of importance

Subgroup analyses assessed whether the outcomes of importance differed by age, sex, prescription or duration of mAb therapy, prescription of maintenance OCS, asthma control or history of frequent asthma attacks.

Outcomes of importance scores did not differ by age (≥65 years (52%) compared to <65 years). Females, however, rated wanting to improve their overall quality of life higher, uniformly rating this item at the highest score (mean±sd 6±0), compared to males (5.70±0.60; p=0.03). Additionally, females rated wanting to improve their workplace attendance and productivity higher than males (mean±sd: 5.30±1.56 versus 3.57±2.71, p=0.01, respectively). Wanting to be more social was also rated more important to females than males (mean±sd: 4.90±1.21 versus 3.90±1.90, respectively, p=0.04), as was wanting to be less tired (mean±sd: 5.70±0.57 versus 4.70±4.60, p=0.01).

Wanting to be less breathless was rated as more important in those who had inadequate asthma control (ACQ ≥1.5; n=31, 62%), with a mean rating of 5.84±0.45 compared to those with adequate control (5.32±1.29, p=0.04).

Asthma attack-prone participants (>2 exacerbations in the past year; n=31, 62%) rated improved quality of life significantly higher (mean±sd: 5.97±0.18) than those without frequent attacks (5.58±0.69, p=0.004), although this was ranked highly in both groups. There was also significantly higher rating of “I want to improve my workplace productivity and attendance” in those who were prone to asthma attacks (mean±sd: 5.00±1.97) compared to those who were not (3.05±2.74, p=0.01), although the majority were not currently employed.

There were no significant differences in outcome ratings for the subgroup analyses for participants prescribed mAb therapy to those that were not; the duration of mAb therapy prescription; and those who were on maintenance OCS (daily) compared to those who were not.

Component 2: Treatment aspect preferences

Considerations for making a medication choice

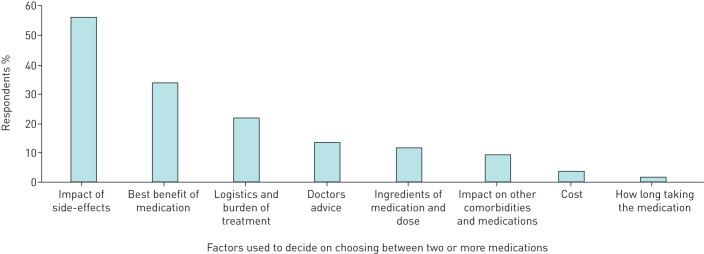

The self-reported aspects of treatment that patients considered important when choosing between medications are shown in figure 3. Overwhelmingly, the medication's side-effect profile was considered the main driver of choice, followed by the medication's beneficial effects on symptoms (figure 3). Logistics (such as how you receive the medication, and how frequently) followed by doctors' advice were the next highest-rated considerations (figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of the preferences nominated by participants when asked to select their top five.

Ranking the aspects of treatment

When asked to rank the most important aspects of treatment, the majority of respondents (92%) stated it was related to asthma characteristics, e.g., “how the medication improves their asthma” (improvement in symptoms, reduction in OCS, improvement in asthma-related quality of life). Side-effect profile was the second most preferred characteristic (64% of respondents). Logistics, i.e. how the medication is administered (tablet, injection), was considered third most important by 56% of respondents, and cost (presented as cost to the patient) was considered the least important by 58% of respondents.

Hypothetical scenarios

The main properties of each hypothetical medication are shown in figure 4a. When asked to choose a medication based on “asthma treatment efficacy”, the most preferred treatment was medication C (based on benralizumab; 94%; figure 4b). The second scenario, assessing logistic-related characteristics, medication D (based on azithromycin; a tablet), was the most preferred treatment chosen by 82% (figure 4b). Medication D was also most preferred in terms of side-effects profile (n=56%; figure 4b).

FIGURE 3.

Self-reported factors used to decide when given a choice of medication.

When asked to consider asthma treatment efficacy, logistics and side-effect profile collectively in the fourth scenario, the majority (68%) selected medication C as their most preferred treatment (based on benralizumab), with 26% choosing medication D (based on azithromycin; figure 4b). Participants provided a reason as to why they chose a particular medication. Of those that selected medication C (based on benralizumab; n=34), the major choice drivers were the effect on “number or severity of asthma attacks” (41.2%), followed by the greatest reduction in OCS use (35.3%), overall quality-of-life improvement (32.4%) and the best side-effect profile (29.4%). Of the people who chose medication D (based on azithromycin; n=13), the majority (76.9%) selected this option because it was a tablet, 30.8% felt it provided the best balance in terms of asthma treatment efficacy, logistic characteristics and side-effects, and just over half of the participants felt it had the best side-effect profile (53.8%).

Discussion

We report the results of a survey examining patient preferences relating to add-on asthma medications with the aim of providing new knowledge to assist with person-centred severe asthma care. People with severe asthma rated all the outcomes shown as important; however, the highest ranked treatment priorities were improvement in quality of life, reducing the number and severity of asthma attacks, increasing physical activity, OCS reduction and being less breathless. Using hypothetical scenarios, we assessed “trade-offs” made by patients in the decision-making providing an improved understanding of the outcomes and aspects of treatment that are important to patients with severe asthma, including medication efficacy versus side-effects. These data will inform the delivery of shared decision-making among patients and clinicians.

Quality of life was considered the most important outcome that people wanted to improve. Impairments in quality of life have been consistently illustrated among people with severe asthma and have largely remained unchanged over the past decade [18, 19, 27, 28]. The majority of patients in this study were already prescribed mAb therapy; nonetheless, this did not reduce their endorsement of wanting better quality of life or fewer attacks, indicating that whilst these medications are known to improve these asthma outcomes, patients still see room for further improvement.

The experience of asthma attacks and OCS use are known to contribute significantly to the burden experienced by people with severe asthma [19, 29]. Clinical trials of azithromycin and mAb therapies [9, 30, 31] have demonstrated efficacy in reducing asthma attacks; however, both attacks and OCS continue to play a central role in uncontrolled severe asthma [32]. This study demonstrates that even with the introduction of add-on medications for severe asthma, there remains a residual burden with patients wanting to reduce asthma attacks and OCS use as a priority, regardless of whether they are taking OCS on a daily basis or as needed.

Medication characteristic preferences

Shared decision-making between patients and clinicians leads to improvements in chronic disease management and increases the likelihood of treatment adherence [15]. As more severe asthma treatment options become available, understanding what characteristics patients consider a priority in terms of treatment outcomes is increasingly important and may assist clinician's decision-making. However, knowing how to convey relevant information about the benefits, disadvantages and points of difference of these treatments remains a challenge. This present study revealed that patients place high-value on medication efficacy, specifically on the treatment's ability to reduce the number and severity of asthma attacks, reduce OCS use and improve quality of life. Whilst “asthma treatment efficacy” was considered the most important factor for decision-making, approximately one-quarter of patients selected a medication that was not consistent with this preference when the hypothetical scenarios were presented collectively. These participants traded off asthma treatment efficacy in favour of how the medication is administered and the side-effect profile, and their preferred medication was a tablet, medication D, based on azithromycin (figure 4a). This indicates that for a subgroup of patients, a medication's performance in improving asthma-related outcomes alone is not enough information for them to make a fully informed choice regarding their treatment options. Additionally, cost was not considered a priority; however, this is likely to vary depending on cost to the patient within different healthcare systems. In Australia, several add-on asthma medications for severe asthma are subsidised under the pharmaceutical benefits scheme, so out of pocket expenses to people with certain severe asthma phenotypes are minimal. We acknowledge that results may differ among different countries with varied healthcare systems. In this study the majority of participants were currently prescribed mAb therapy, suggesting that their preferences are based on their real-life experiences for participants within a severe asthma clinic. Identifying patient preferences or priorities in relation to their real-world experience of current or future severe asthma add-on treatments is essential to the foundation of real-world shared decision-making.

There are several limitations to the current study. Although the survey tool was not a validated instrument, it enabled an understanding of what treatment aspects people with severe asthma consider important in terms of their medications, and the outcomes they would like to improve. Whilst it was the aim of the study to understand what people with severe asthma want from add-on asthma treatments, whether they be current, past or future treatments, the survey sample consisted largely of patients who were prescribed mAb therapy. There was, however, no difference between those prescribed mAb therapy versus those that were not in the respective sub-analysis. We acknowledged that we were underpowered in this particular analysis; therefore, we are unable to determine the impact that current, past or future add-on asthma treatments have on these outcomes of importance. Nevertheless, understanding patients' preferences and priorities are important aspects of shared decision-making regardless of their current or future treatment experience. Further, this survey was conducted on a relatively small sample size who were recruited from one respiratory clinic. Experiences with mAb therapy prior to enrolment were not recorded and adherence to current treatment was not investigated; however, patients receive monitoring with the administration of mAb therapies, so we can be confident of adequate adherence at least with mAbs. This is an important observation, however, as it highlights that despite receiving these treatments, patients with severe asthma continue to suffer a symptom and quality-of-life burden. This is consistent with data from a large survey of people with severe asthma. This residual burden needs to be addressed in future asthma research and practice.

The medications used in the “medication characteristic preferences section” were presented to elicit what aspects of a medication patients consider important when making a medication choice. Presenting a clear winner, in terms of treatment efficacy from a patient's perspective, enabled us to determine what was the most important outcome when all treatment aspects were traded off together. Further, whilst the medication side-effects listed were based on those that were common across all medications, for readability, an exhaustive list of medication attributes and side-effects were not included. More extensive work examining which side-effects would be weighted more heavily in decision-making could be of benefit in this population. Additionally, the hypothetical medication scenarios were based only on those mAbs available for prescription at the time of the study. Given this, there were no scenarios that represented “Dupilumab” or “Reslizumab”.

These factors may limit the generalisability of the findings. Further, it is a limitation of the current study that consumers did not review the list of priorities during the development of the survey; however, the survey items were derived from prior qualitative research in the population of interest [17–19]. We acknowledge that we did not provide an exhaustive list of potential outcomes of importance, but we believe the inclusion of open-ended questions about additional outcomes will have overcome this limitation.

Conclusions

This study highlights what aspects of treatment and outcomes people with severe asthma regard as important. Some of these outcomes, such as breathlessness, inability to be physically active and impaired sleep, are not current targets of severe asthma treatments and are infrequently measured in clinical trials or assessed in routine asthma management. Given these outcomes are of great importance to patients, and are of high clinical relevance [33, 34], future research focussing on the development of interventions that improve these outcomes (both pharmacological and non-pharmacological) are needed. Further, patients consider asthma treatment efficacy as a priority when deciding what medication to take, but also want to know the burden of the medication side-effects to enable them to evaluate the overall improvements to their quality of life. Together these data can inform patient-centred development of new severe asthma treatments and patient-centred models of care.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00497-2020.SUPPLEMENT (245.7KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Support statement: This study was supported by the Centre of Research Excellence in Severe Asthma.

This article has supplementary material available from openres.ersjournals.com

Conflict of interest: V.L. Clark reports grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council during the conduct of the study and personal fees from AstraZeneca outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: P.G. Gibson reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis, and grants from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: V.M. McDonald reports grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council during the conduct of the study; grants from the Hunter Medical Research Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council, and the John Hunter Hospital Charitable Trust Research, and grants and personal fees from GSK, Menarini and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Pavord ID, Beasley R, Agusti A, et al. . After asthma: redefining airways diseases. Lancet 2018; 391: 350–400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30879-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald VM, Gibson PG. Exacerbations of severe asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2012; 42: 670–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.03981.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonald V, Kennington E, Hyland M. Understanding the experience of people living with severe asthma. In: Chung K, Gibson P, eds. Severe Asthma (ERS Monograph). Sheffield, European Respirtory Society, 2019; pp. 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald VM, Hiles SA, Godbout K, et al. . Treatable traits can be identified in a severe asthma registry and predict future exacerbations. Respirology 2019; 24: 37–47. doi: 10.1111/resp.13389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. . Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 390: 659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upham JW, Chung LP. Optimising treatment for severe asthma. Med J Aust 2018; 209: S22–S27. doi: 10.5694/mja18.00175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, et al. . Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 2115–2127. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31324-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME, et al. . Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med 2015; 3: 355–366. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00042-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al. . Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 651–659. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60988-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark VL, Gibson PG, Genn G, et al. . Multidimensional assessment of severe asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respirology 2017; 22: 1262–1275. doi: 10.1111/resp.13134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiles SA, McDonald VM, Guilhermino M, et al. . Does maintenance azithromycin reduce asthma exacerbations? An individual participant data meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1901381. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01381-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greening AP, Stempel D, Bateman ED, et al. . Managing asthma patients: which outcomes matter? Eur Respir Rev 2008; 17: 53–61. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00010801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osman LM, McKenzie L, Cairns J, et al. . Patient weighting of importance of asthma symptoms. Thorax 2001; 56: 138–142. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.2.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making – the pinnacle patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, et al. . Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181: 566–577. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0907OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelhorn HL, Balantac Z, Ambrose CS, et al. . Patient and physician preferences for attributes of biologic medications for severe asthma. Patient Prefer Adherence 2019; 13: 1253–1268. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S198953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. . International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 343–373. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00202013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eassey D, Reddel HK, Foster JM, et al. . “…I've said I wish I was dead, you'd be better off without me”: a systematic review of people's experiences of living with severe asthma. J Asthma 2019; 56: 311–322. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2018.1452034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster JM, McDonald VM, Guo M, et al. . “I have lost in every facet of my life”: the hidden burden of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700765. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00765-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones KA, Gibson PG, Yorke J, et al. . Attack, flare-up, or exacerbation? The terminology preferences of patients with severe asthma. J Asthma 2019: 1–10. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1665064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheung KL, Wijnen BFM, Hollin IL, et al. . Using best-worst scaling to investigate preferences in health care. Pharmacoeconomics 2016; 34: 1195–1209. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0429-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker MH. The Health Belief Model and sick role behavior. Health Educ Monogr 1974; 2: 409–419. doi: 10.1177/109019817400200407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q 1984; 11: 1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman S, Dale P, Svedsater H, et al. . Modelling the effect of beliefs about asthma medication and treatment intrusiveness on adherence and preference for once-daily vs. twice-daily medication. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2017; 27: 61–61. doi: 10.1038/s41533-017-0061-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svedsater H, Leather D, Robinson T, et al. . Evaluation and quantification of treatment preferences for patients with asthma or COPD using discrete choice experiment surveys. Respir Med 2017; 132: 76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King MT, Hall J, Lancsar E, et al. . Patient preferences for managing asthma: results from a discrete choice experiment. Health Econ 2007; 16: 703–717. doi: 10.1002/hec.1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stubbs M, Clark V, McDonald V. Living well with severe asthma. Breathe 2019; 15: e40–e49. doi: 10.1183/20734735.0165-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katsaounou P, Odemyr M, Spranger O, et al. . Still Fighting for Breath: a patient survey of the challenges and impact of severe asthma. ERJ Open Res 2018; 4: 00076-02018. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00076-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyland ME, Whalley B, Jones RC, et al. . A qualitative study of the impact of severe asthma and its treatment showing that treatment burden is neglected in existing asthma assessment scales. Qual Life Res 2015; 24: 631–639. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0801-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niebauer K, Dewilde S, Fox-Rushby J, et al. . Impact of omalizumab on quality-of-life outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe allergic asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 96: 316–326. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61242-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Busse W, Corren J, Lanier BQ, et al. . Omalizumab, anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 108: 184–190. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramsahai JM, Wark PA. Appropriate use of oral corticosteroids for severe asthma. Med J Aust 2018; 209: Suppl. 2, S18–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frostad A, Soyseth V, Andersen A, et al. . Respiratory symptoms as predictors of all-cause mortality in an urban community: a 30-year follow-up. J Intern Med 2006; 259: 520–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01631.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cordova-Rivera L, Gibson PG, Gardiner PA, et al. . A systematic review of associations of physical activity and sedentary time with asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; 6: 1968–1981.e1962. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00497-2020.SUPPLEMENT (245.7KB, pdf)