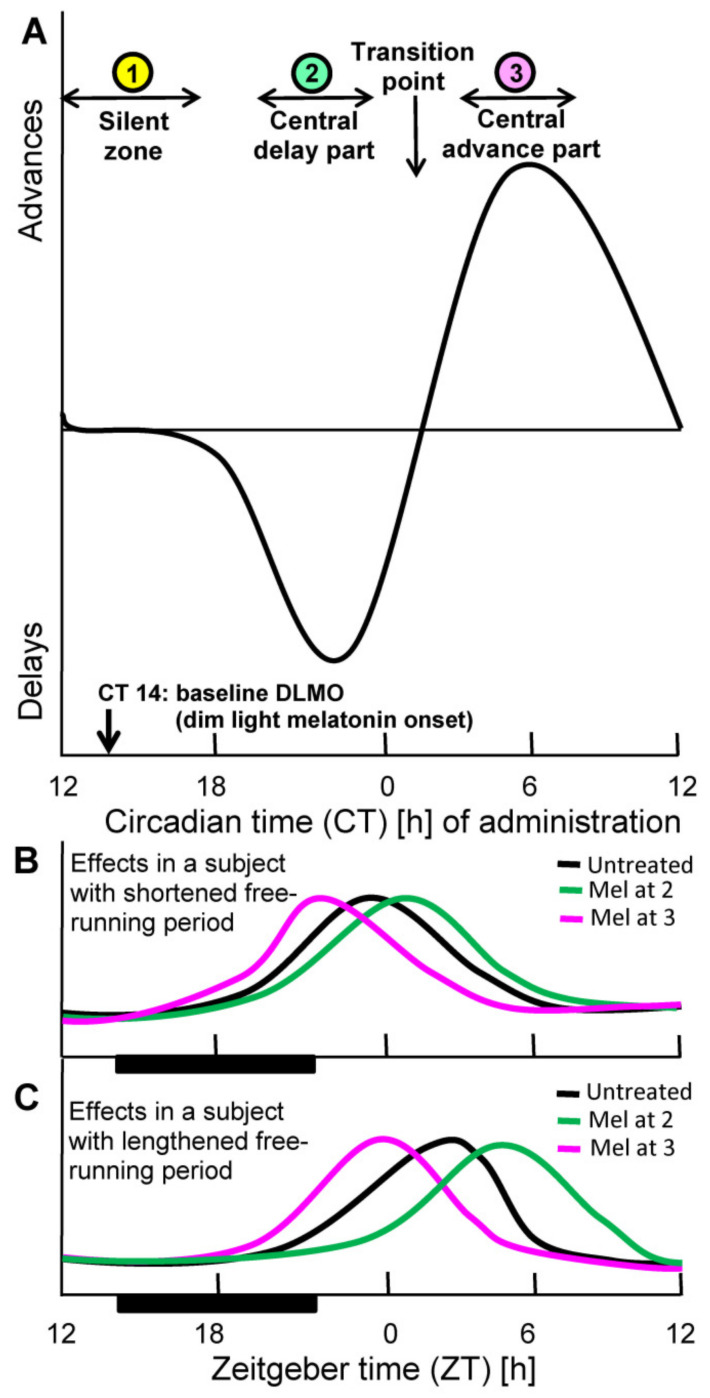

Figure 1.

Phase resetting by melatonin according to the Phase Response Curve (PRC). (A): Schematic depiction of human PRC for low doses of immediate-release melatonin. The curve is based on data by Lewy et al., obtained with 0.25 mg melatonin [26]. Original data have been omitted for improving comprehensibility of the principles. Notably, the extent of phase shifts (here: range of a very few hours) and some other details of such PRC curves are also dose-dependent. However, higher doses such as 10 mg do not necessarily increase, but may rather reduce the amplitude of the PRC [61]. PRCs are determined under free-running conditions, in which the phases of the spontaneous period are referred to circadian time (CT) (one free-running cycle = 24 subjective hours). The influences of resetting capacity are also detectable under entrained conditions and become evident by changes in the phase positions of prominent features of circadian rhythms, such as maxima. (B,C): Predicted effects of melatonin in different phases of the PRC, in subjects with shortened (B) or lengthened (C) spontaneous periods, however, under synchronized conditions in a light-dark cycle (black bars: darkness). Under synchronized conditions, time is standardized as Zeitgeber time (ZT); in a 12:12 h light/dark cycle, ZT 0 corresponds to light onset; under deviating light/dark cycles, ZT is adjusted to the middle of dark phase. For facilitating comprehensibility, a notional rhythm with a maximum in the morning has been depicted. A rhythm of an oscillator gene in the SCN would be preferable, but these data are not available for the human. Rhythms of oscillator genes in other human cells or tissues have been reported, but preclinical studies have shown that their phasing deviates between tissues, sometimes strongly, and are, therefore, not suitable.