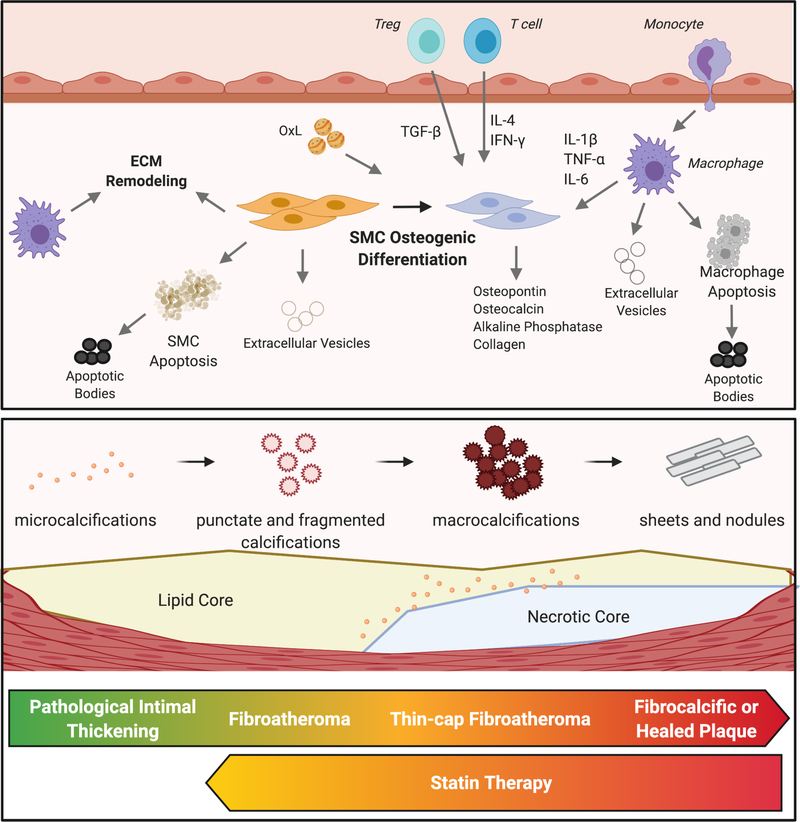

Figure 1. Calcification within atherosclerotic plaques.

Osteogenic differentiation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) is a central process to the calcification of lesions. These cells become phenotypic osteoblasts, able to calcify surrounding tissue through the production of a variety of stimuli. Inflammation, driven by both innate and adaptive immune cells, promotes this SMC phenotypic shift. Oxidized lipids (OxL) promote metabolic and phenotypic changes in SMCs and macrophages as well as by augmenting local inflammation. Apoptosis of macrophages and SMCs generate apoptotic bodies that may become calcified. Similarly, extracellular vesicles released by SMCs or macrophages can also become calcified and aggregate into microcalcifications. Macrophages and SMCs produce factors that remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM), providing a scaffolding on which microcalcifications can aggregate into macroscopic calcifications. As atherosclerotic lesions progress, microcalcifications and fragmented calcifications coalesce to form macrocalcifications. Late-stage plaques or those that have ruptured and healed are characterized by dense sheets of calcium. Statin therapy appears to promote a reversal of macrocalcifications to microcalcifications in mice.