Abstract

Background

Despite identified inequities and disparities in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ+) health, past studies have shown little or no education at the medical school or residency level for emergency physicians. With increased focus on health inequities and disparities, we sought to reexamine the status of sexual and gender minority health education in U.S. emergency medicine (EM) residencies.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to determine how many EM residencies offer education on LGBTQ+ health. Secondary objectives included the number of actual versus preferred hours of LGBTQ+ training, identification of barriers to providing education, and correlation of education with program demographics. Finally, we compared our current data with past results of our 2013 study.

Methods

The initial survey that sought to examine LGBTQ+ training in 2013 was used and sent in 2020 via email to EM programs accredited by the American Council for Graduate Medical Education who had at least one full class of residents in 2019. Reminder emails and a reminder post on the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine listserv were used to increase participation.

Results

A total of 229 programs were eligible, with a 49.3% response rate (113/229). The majority (75%) offered education content on LGBTQ+ health, for a median (IQR) of 2 (1–3) hours and a range of 0 to 22 hours. Respondents preferred more hours of education than offered (median desired hours = 4, IQR = 2–5 hours; p < 0.001). The largest barrier identified was lack of time in curriculum (63%). The majority of programs had known LGBTQ+ faculty and residents. Inclusion and amount of education hours positively correlated with presence of LGBTQ+ faculty or residents; university‐ and county‐based programs were more likely to deliver education content than private groups (p = 0.03). Awareness of known LGBTQ+ residents but not faculty differed by region, but there was no significant difference in actual or preferred content by region.

Conclusion

The majority of respondents offer education in sexual and gender minority health, although there remains a gap between actual and preferred hours. This is a notable increase from 26% of responding programs providing education in 2013. Several barriers still exist, and the content, impact, and completeness of education remain areas for further study.

INTRODUCTION

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ+) patients are ubiquitous in emergency medicine (EM) and vulnerable to health inequities and disparities. 1 Despite this, emergency physicians traditionally have had limited training in LGBTQ+ health. A study of medical school curricula in 2011 found a median of 5 hours of instruction on LGBTQ+ health, with one‐third having no instruction during clinical years. 2 The first study to examine LGBTQ+ education in EM training in 2013 found that the majority (74%) of EM residency program respondents did not offer education specific to LGBTQ+ health, with a median of 0 minutes of content. 3 EM residents have reported decreased comfort in caring for and obtaining a history from LGBTQ+ patients compared to sexual and gender majorities. 4 , 5

Since the 2013 survey on LGBTQ+ education in EM residencies, there has been growing literature and education by organizations on LGBTQ+‐specific health. 4 , 6 In 2016, the National Institutes of Health designated sexual and gender minorities as a health disparity population. 7 Additional societal influences such as marriage equality, increasing visibility, awareness, and acceptance of LGBTQ+ individuals have also occurred. 8 Despite this, the majority of medical students in a 2017 study desired more education than they received on LGBTQ+ health, suggesting that the gap in LGBTQ+ education has not closed in undergraduate medical education. 9 More recent surveys from non‐EM residencies show that a substantial gap in actual versus preferred hours of LGBTQ+ education exists at the graduate medical education level. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 The 2019 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine has added gender identity, sexual orientation, and transgender care to the core content adopted by the American Board of Emergency Medicine. 17 It is unclear if these developments have led EM residency programs to implement or expand LGBTQ+‐specific education in their curricula or if a gap in EM training remains.

In this study, we sought to determine the current state of sexual and gender minority education in U.S. EM residency programs. Moving beyond the original needs assessment, we also hypothesized that more programs may be providing LGBTQ+ education than in 2013.

METHODS

We used a 2013 survey of residency program directors of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)‐accredited EM residency programs. 18 That survey was pilot tested at four EM programs prior to use and publication. This study was determined to be exempt by the institutional review board at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Survey content and administration

A 14‐question survey from the original 2013 survey was used (Data Supplement S1, available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10580/full). The survey inquired about program demographics, presence of LGBTQ+ education, and hours of content both actual and preferred. The survey was distributed to programs accredited before July 1, 2019, that would have completed at least 1 full year of resident education based on their initial accreditation date. These criteria resulted in 229 eligible EM programs. Program directors were contacted directly by their email listed in the ACGME website of accredited programs using an anonymous link created in Qualtrics on May 3, 2020. If no email was available, the survey was sent to the program contact listed with a request to forward to the program director. Two reminders were sent within the following 2 weeks. A final reminder was posted on the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine (CORD) listserv on July 8, 2020. Respondents were provided the email address for the primary author for concerns or questions, but none were forwarded.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was identifying the percentage of programs that had presented LGBTQ+ content. This content included a dedicated lecture, incorporation of content into other instructional formats (e.g., simulation), or journal club content. Secondary outcomes included the number of actual hours of LGBTQ+ health education presented in the past year and the number of preferred hours. Secondary outcomes also included any program demographic correlation with the amount of LGBTQ+ education, both actual and preferred; perceived barriers to LGBTQ+ education (respondents could choose more than one); and comparison of results with the original 2013 survey.

Data analysis

Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. Actual and preferred time spent on LGBTQ+ health education (in hours) were described using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Hours spent on LGBTQ+ health education were compared across demographic characteristics using the Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests. The actual number of hours and the preferred number of hours were compared using the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test and Spearman correlation. Sets of categorical variables were compared using the chi‐square test. For analyses involving geographic region, U.S. Census Bureau standards for regions and divisions of the United States were used. 19 Analyses were conducted using SPSS (v. 26; SPSS, Inc., Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

A total of 113 responses from 229 eligible programs were received (response rate 49.3%). Program demographics are shown in Table 1. The majority of responding programs (75%) reported offering educational didactic on LGBTQ+ health (Table 2). Programs had a median (IQR) of 2 (1–3) hours and a range of 0 to 22 hours of content. Fifty‐five percent incorporated sexual and gender minority health into other didactics, and 26% had a journal club related to LGBTQ+ health.

Table 1.

Program demographics

| Demographic | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Response by region | ||

| Northeast | 28 | 24.8 |

| Midwest | 29 | 25.7 |

| South | 35 | 30.9 |

| West | 21 | 18.6 |

| Metropolitan area size | ||

| <100,000 | 11 | 9.7 |

| 100,000–250,000 | 20 | 17.7 |

| 250,000–1,000,000 | 37 | 32.7 |

| >1,000,000 | 45 | 39.8 |

| Do you currently have out LGBTQ+ faculty as part of your residency program | ||

| Yes | 78 | 69.0 |

| Not that I’m aware of | 35 | 31.0 |

| Do you currently have out LGBTQ+ residents as part of your residency | ||

| Yes | 92 | 81.4 |

| Not that I’m aware of | 21 | 18.6 |

| Faculty employer type | ||

| University | 72 | 63.7 |

| Private group | 8 | 7.1 |

| Community hospital | 16 | 14.2 |

| County hospital | 15 | 13.3 |

| Other | 2 | 1.8 |

| Employer offers same‐sex domestic partner benefits | ||

| Yes | 69 | 61.1 |

| No | 7 | 6.2 |

| Don't know | 37 | 32.7 |

| Employer protections against LGBTQ+ discrimination/harassment | ||

| Yes | 71 | 62.8 |

| No | 2 | 1.8 |

| Don't know | 40 | 35.4 |

Abbreviation: LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning.

Table 2.

Program responses

| Question | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Has your program ever presented didactic lectures focused on LGBTQ+ health issues? | ||

| Yes | 85 | 75.2 |

| No | 28 | 24.8 |

| Has your program incorporated LGBTQ+ health concerns into general lecture topics where LGBTQ+ patients are disproportionately affected? | ||

| Yes | 62 | 54.9 |

| No | 51 | 45.1 |

| How many hours of didactic lectures on LGBTQ+ health issues did your program present in 2019? | Median (IQR) = 2 (1–3) h; range = 0–22 h | |

| How many didactic hours per year should be devoted to LGBTQ+ health issues? | Median (IQR) = 4 (2–5) h; range = 0–20 h | |

| Has your program ever conducted a journal club or other nondidactic activity related to LGBTQ+ health issues? | ||

| Yes | 29 | 25.7 |

| No | 84 | 74.3 |

| Barriers you have encountered to integrating LGBTQ+ topics into your curriculum and patient care | ||

| Lack of interested faculty | 24 | 21.2 |

| Lack of funding | 9 | 8.0 |

| Lack of time | 71 | 62.8 |

| Perception education is not needed | 17 | 15.0 |

| Opposition to inclusion of LGBTQ+ health topics | 2 | 1.8 |

| No barriers | 30 | 26.5 |

| Other | 14 | 12.4 |

Abbreviation: LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning.

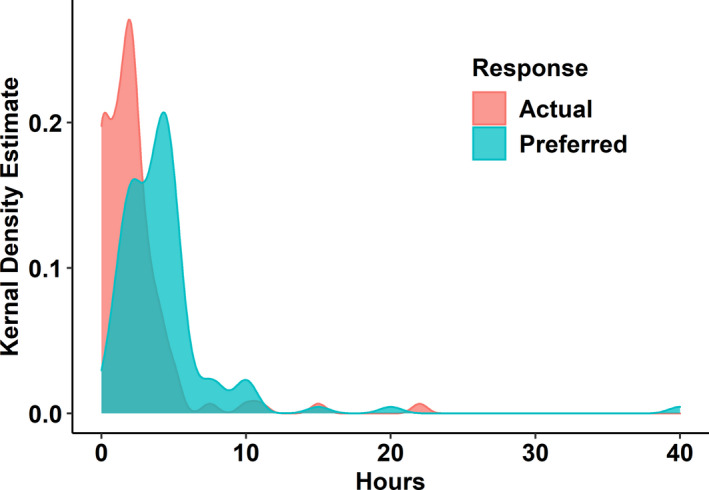

Respondents preferred more hours of content than programs delivered (median = 4 hours, IQR = 2–5 hours; p < 0.001; Figure 1, Table 2). The numbers of actual and preferred hours were moderately positively correlated (r = 0.46, p < 0.001). Neither actual hours (p = 0.09) nor preferred hours (p = 0.25) differed by regions.

Figure 1.

Actual versus desired hours of LGBTQ+ education in EM training programs. Smoothed histograms were generated using kernal density estimates. LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning

The majority of respondents identified with larger metropolitan population areas, with the largest category being metropolitan areas over 1 million (39.8%; Table 1). Neither actual (p = 0.09) nor preferred (p = 0.38) hours differed by metropolitan size category. The number of actual or preferred hours of LGBTQ+ education also did not differ by region (p = 0.09; Table 3).

Table 3.

Actual and preferred hours of LGBTQ+ health content by demographic characteristic

| Grouping | Actual, median (IQR) | p‐value a | Preferred, median (IQR) | p‐value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2 (1–3) | — | 4 (2–5) | — |

| Region | 0.09 | 0.25 | ||

| Midwest | 2 (1–2.75) | 3 (2–4) | ||

| Northeast | 2 (0.5–2.5) | 4 (2.4–5) | ||

| South | 2 (0–2) | 4 (2–5) | ||

| West | 3 (1–4.5) | 4 (2.75–8.75) | ||

| Employer type | 0.02 | 0.22 | ||

| Community hospital | 2 (1–2.5) | 4 (2.25–5.75) | ||

| County hospital | 2 (1–4) | 4 (2–5) | ||

| Other b | 8.5 | 8.5 | ||

| Private group | 0 (0–0.75) | 2 (1–3.5) | ||

| University | 2 (1–3) | 4 (2.25–5) | ||

| Metropolitan area size | 0.09 | 0.38 | ||

| <100,000 | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–4) | ||

| 100,000–250,000 | 2 (0–2) | 4 (2–5) | ||

| 250,000–1,000,000 | 1.5 (0.5–2.5) | 4 (2–5) | ||

| >1,000,000 | 2 (1–3) | 4 (2.5–5.5) |

Abbreviation: LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning.

Separate Kruskal–Wallis Tests for region, employer type, and metropolitan size.

Sample size was insufficient to compute IQR.

The number of actual hours delivered differed by faculty employer type (p = 0.02; Table 3). Specifically, universities and county programs had more hours than private groups (Bonferroni‐adjusted p = 0.03). Programs with university faculty employer delivered a median (IQR) of 2.0 (1–3) hours of content, county programs delivered a median (IQR) of 2.0 (1–4) hours, and private groups had a median (IQR) of 0 (0–0.75) hours. The number of hours delivered by community hospital employers (median = 2.0, IQR = 1–2.5) did not significantly differ from university or county hospital employers. Preferred hours however did not differ by setting (p = 0.22).

Among benefits offered to LGBTQ+ residents and faculty, 61% reported same‐sex domestic partner benefits, and 63% offered employment protection against discrimination or harassment. The association between employer type and benefits was not significant (χ2(8) = 3.56, p = 0.89). A large minority of respondents in both categories (33% and 35%, respectively) did not know if these basic benefits were available for their resident employees.

The majority of respondents were aware of known LGBTQ+ faculty (69%) and residents (81%). Awareness of known LGBTQ+ residents differed by region (χ2(3) = 14.2, p = 0.003): Northeast (96.6%), Midwest (93.1%), West (71.4%), and South (65.7%). Awareness of known LGBTQ+ faculty did not differ by region (χ2(3) = 2.35, p = 0.50): West (81.0%), Northeast (72.4%), Midwest (65.5%), and South (62.9%). LGBTQ+ resident awareness differed by employer type (χ2(4) = 14.86, p = 0.005): county hospital (86.7%), university (78.1%), community hospital (43.8%), private group (25.0%), and other (0%). LGBTQ+ faculty awareness differed by employer type (χ2(4) = 21.58, p < 0.001): university (89%), county hospital (80%), community hospital (75%), other (50%), and private group (37.5%).

Programs with known LGBTQ+ faculty were more likely to deliver LGBTQ+ didactics (86.1% vs. 51.4%, p < 0.001), to incorporate LGBTQ+ issues into other didactics (65.8% vs. 31.4%, p = 0.001), and to have journal clubs focused on LGBTQ+ issues (32.9% vs. 8.6%, p = 0.006). Similarly, programs with known LGBTQ+ residents were more likely to deliver LGBTQ+ didactics (82.8% vs. 42.9%, p < 0.001), to incorporate LGBTQ+ issues into other didactics (65.6% vs. 9.5%, p = 0.001), and to have journal clubs focused on LGBTQ+ issues (30.1% vs. 4.8%, p = 0.02).

The largest barrier encountered by programs was lack of time in the curriculum (63%). Frequently cited barriers also included lack of interested faculty (21%) and perception that this education was not needed (15%). Other barriers were less often cited, and 27% identified no barriers (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Since LGBTQ+ education in EM training programs was first assessed in 2013, there have been many notable changes in academic medicine's focus on LGBTQ+ health, the visibility of LGBTQ+ individuals, and acceptance of LGBTQ+ rights in society. 8 The ACGME has included health disparities as an important content of Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER), and EM model of clinical practice will now include gender identity and sexual orientation. 17 , 20 Despite the above changes, more recent studies demonstrate a continued knowledge gap in LGBTQ+ health in other medical specialties, and no reexamination of the state of LGBTQ+ health education in EM has been done. 4 , 9 , 21 , 22

We hypothesized that organizational and societal changes since 2013 would lead to an increase in the percentage of programs that delivered LGBTQ+ health content in EM and the amount of content for those that did provide it. We found that 75% of respondents offered LGBTQ+ content in 2020, a marked increase from 26% in 2013. 3 The median amount of content increased from 0 minutes to 2 hours in this study and utilized several modalities including general didactics and journal clubs. There remains a gap in actual versus preferred hours, with programs preferring twice as much content as they delivered. Important barriers focused most on time constraints (63%) as programs struggle with an increasing amount of critical content in a limited time period. A small number of programs cited perception of lack of need as a barrier (15%), and only one respondent (0.9%) wanted no education on LGBTQ+ health. In our previous study the majority responded perceived lack of need as the largest barrier (59%), and 16% of program directors did not desire LGBTQ+ education. 3 These shifts from 2013 suggest that a large majority of respondents recognize LGBTQ+ education as an important component in EM residency training. Programs that do not include LGBTQ+ health education should reference the 2019 Model of the Clinical Practice in Emergency Medicine that specifies education on sexual and gender minorities as core content in EM training.

Respondent demographics in terms of metropolitan size and program type were similar to the previous distributions found in 2013, with the majority of respondents being in a metropolitan area over 1 million and identifying as a university‐based program. 3 In this study we found no statistical difference in actual or preferred hours of content by metropolitan size as a category. This is similar to what was found in the 2013 study.

We did find that respondents identified as employed by private groups have less education delivered but not preferred and were less likely to be aware of LGBTQ+ residents and faculty. There were no differences in provision or knowledge of same‐sex domestic partner benefits or employment discrimination protections compared to other employer types. Because the small number of respondents in this category, perhaps these results although statistically significant are not truly representative of this group as a whole. There is no definitive reference for program or employer type to confirm our study distribution is representative, although the distribution is similar to our 2013 survey. Private group‐based programs should examine their curriculum content as this may be an opportunity for further development to align with the 2019 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine.

We found that the majority of responding programs know of openly LGBTQ+ faculty and residents. Programs with known LGBTQ+ faculty were more likely to deliver LGBTQ+ content as was previously found. 3 In this study 69% of responding programs knew of LGBTQ+ faculty, and 81% of residents knew. For residents, this is a notable increase from 2013 where similar program demographics yielded a result of only 56%. 3 This may represent increased program director awareness, increased resident visibility, or increased resident comfort being out in residency. LGBTQ+ resident awareness did vary by region (χ2(3) = 14.2, p = 0.003)—Northeast (96.6%), Midwest (93.1%), West (71.4%), and South (65.7%)—whereas LGBTQ+ faculty awareness did not. Perhaps reputations and perceptions of tolerance affect either visibility or regional program selection by LGBTQ+ EM applicants.

Protections and benefits for LGBTQ+ employees were unknown by one‐third of program directors who responded. Despite marriage equality, not all LGBTQ+ individuals in long‐term relationships have married, and for some same‐sex domestic partner benefits remain of interest. Protection against employment discrimination for LGBTQ+ status is of fundamental concern to LGBTQ+ residents and faculty. We suggest that program directors should be aware and inclusive by knowledge if protections and benefits for LGBTQ+ residents exist.

The need for LGBTQ+ health education has been clearly demonstrated, and advances in quantity are noted with this study. Education on LGBTQ+ health is not universal, despite its recent incorporation the in 2019 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. However, a defined curriculum is lacking and likely varies by program. Content and learning objectives that address continued barriers are a logical area of future effort and examination.

LIMITATIONS

Data were self‐reported and thus subject to response bias. Although the survey was originally pilot tested, there may be individual interpretation of questions that has the potential to affect results. The survey was sent to program directors, who may defer curriculum development to other faculty, which may affect the accuracy of their report. Because it was an anonymous survey, we had no mechanism to eliminate duplicate responses but attempted to limit this possibility by sending a specific link to each program director using Qualtrics. Although we found some correlations based on employer type, these must be interpreted with caution. Both results were self‐reported, and we cannot verify independently the validity of their self‐reported classifications. Although our respondents include 49.3% of all EM training programs with residents in 2019, it is possible that nonrespondents may have significantly affected outcomes.

In seeking to assess progress since our initial study, we used a broad inclusive definition of LGBTQ+ in our survey. The authors acknowledge and agree that sexual orientation and gender identity are distinct and separate areas that, although commonly included in aggregate, each deserve separate and dedicated study, education, and approaches. It is not possible, therefore, to determine what degree of education actual or desired are on gender identity, sexual orientation, or both.

Finally, there are unique challenges to performing research on LGBTQ+ populations. This survey asked program directors for knowledge of LGBTQ+ faculty and residents, which may be unknown or not disclosed to them, especially when a significant number of states do not protect LGBTQ+ employees from employment discrimination. There may also be some bias due to an individual being more likely to either positively or negatively respond if they have strong feelings on this topic.

CONCLUSION

There has been a notable increase in LGBTQ+ education in emergency medicine residency programs since 2013. In our previous paper we suggested a minimum of 2 hours of education, and that was the median found in this study. Despite barriers, the majority of emergency medicine program respondents now provide LGBTQ+ education. With the adoption of LGBTQ+ health and disparities education in the 2019 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine, it is time to move from considering quantity of this topic to also consider quality and content. Future efforts should examine the content provided to address LGBTQ+ health. Our LGBTQ+ population has unique needs and deserves physicians and health care professionals who are knowledgeable and educated in the appropriate assessment, management, and equitable care needed for this unique population group.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design—Joel Moll, Paul Krieger, Lisa Moreno‐Walton, and Sheryl L. Heron. Acquisition of the data—Joel Moll, David Vennard, and Rachel Noto. Analysis and interpretation of the data—Joel Moll, David Vennard, and Timothy Moran. Drafting of the manuscript—Joel Moll, David Vennard, Rachel Noto, and Timothy Moran. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content—Joel Moll, David Vennard, Timothy Moran, Paul Krieger, and Sheryl L. Heron. Statistical expertise—Timothy Moran. Acquisition of funding—not applicable.

Supporting information

Data Supplement S1. 14‐question survey.

Supervising Editor: John Burkhardt

REFERENCES

- 1. Pérez‐Stable E. Sexual and Gender Minorities Formally Designated as a Health Disparity Population for Research Purposes. October 6, 2016. National Institutes of Health. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/directors‐corner/messages/message_10‐06‐16.html.

- 2. Obedin‐Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender‐related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):971‐977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno‐Walton L, et al. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: what do we know? Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(5):608‐611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moll J, Krieger P, Heron SL, Joyce C, Moreno‐Walton L. Attitudes, behavior, and comfort of emergency medicine residents in caring for LGBT patients: what do we know? AEM Educ Train. 2019;3(2):129‐135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hayes V, Blondeau W, Bing‐You RG. Assessment of medical student and resident/fellow knowledge, comfort, and training with sexual history taking in LGBTQ patients. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):383‐387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson N. LGBTQ health education. Acad Med. 2017;92(4):432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pérez‐Stable EJ. Disparities NIoMHaH. Directors Message: Sexual and gender minorities formally designated as a health disparity population for research purposes. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/directors‐corner/messages/message_10‐06‐16.html.

- 8. The Global Divide on Homosexuality Persists. Pew Research Center website. June 25, 2020. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/06/25/global‐divide‐on‐homosexuality‐persists/.

- 9. Nama N, MacPherson P, Sampson M, McMillan HJ. Medical students’ perception of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) discrimination in their learning environment and their self‐reported comfort level for caring for LGBT patients: a survey study. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1368850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sharma A, Shaver JC, Stephenson RB. Rural primary care providers’ attitudes towards sexual and gender minorities in a midwestern state in the USA. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(4):5476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zelin NS, Encandela J, Van Deusen T, Fenick AM, Qin L, Talwalkar JS. Pediatric residents’ beliefs and behaviors about health care for sexual and gender minority youth. Clin Pediatr. 2019;58(13):1415‐1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vinekar K, Rush SK, Chiang S, Schiff MA. Educating obstetrics and gynecology residents on transgender patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(4):691‐699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hirschtritt ME, Noy G, Haller E, Forstein M. LGBT‐specific education in general psychiatry residency programs: a survey of program directors. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(1):41‐45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Massenburg BB, Morrison SD, Rashidi V, et al. Educational exposure to transgender patient care in otolaryngology training. J Craniofacial Surg. 2018;29(5):1252‐1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosendale N, Josephson SA. Residency training: the need for an integrated diversity curriculum for neurology residency. Neurology. 2017;89(24):e284‐e287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morreale MK, Arfken CL, Balon R. Survey of sexual education among residents from different specialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(5):346‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beeson MS, Ankel F, Bhat R, et al. The 2019 model of the clinical practice of emergency medicine. J Emerg Med. 2020;59(1):96‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. List of ACGME Accredited Programs and Sponsoring Institutions. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education website. Accessed December 20, 2020. http://www.acgme.org/ads/public/.

- 19. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States . US Census Bureau website. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps‐data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf.

- 20. Committee Evaluation Committee . CLER Pathways to Excellence: Expectations for an Optimal Clinical Learning Environment to Achieve Safe and High‐Quality Care. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education website. 2019. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/CLER/1079ACGME‐CLER2019PTE‐BrochDigital.pdf.

- 21. Rerucha CM, Runser LA, Ee JS, Hersey EG. Military healthcare providers’ knowledge and comfort regarding the medical care of active duty lesbian, gay, and bisexual patients. LGBT Health. 2018;5(1):86‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chisolm‐Straker M, Willging C, Daul AD, et al. Transgender and gender‐nonconforming patients in the emergency department: what physicians know, think, and do. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(2):183‐188 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Supplement S1. 14‐question survey.