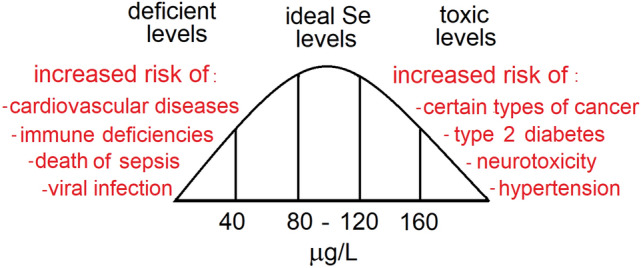

Fig. 1.

U inverted shaped curve for selenium levels in humans. Low selenium status can increase the risk of immunological malfunctioning, cardiovascular diseases, sepsis severity, virus infection, and cognitive deficits. High levels of blood selenium can be associated with an increased risk of developing certain types of cancer (e.g., melanoma and prostate cancer), hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., ALS and Alzheimer's Dementia). In the figure, the ideal levels of selenium were arbitrarily based on the optimal blood activity of glutathione peroxidase (see below). Selenium plays important physiological functions as a part of 25 selenoproteins in humans. At least one half of them are important oxireductases (e.g., 5 glutathione peroxidases (GPxs1-4 and 6); 3 thioredoxin reductases (TrxRs), which are involved in the regeneration of reduced thioredoxin (Trx); methionine sulfoxide reductase, which reduces oxidized methionine sulfoxide to methionine in proteins, 3 deiodinases (DIOs) that are involved in the metabolism of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4); selenophosphate synthetase and several selenoproteins without a clear-defined molecular role in cell physiology. The ideal physiological levels of selenium are not known, but for the blood GPx maximal activity, a level of selenium around 100 µg L−1 is required (Rea et al. 1979; Thomson et al. 1977, 1982). However, how blood GPx activity can predict the whole-body selenoproteins adequate physiological activity is unknown. There is also epidemiological evidence, suggesting that above 120 μg L−1, selenium can start to facilitate the installation of pathological conditions (Bastola et al. 2020)